Abstract

HIV-1 viral assembly requires a direct interaction between a Pro-Thr-Ala-Pro (“PTAP”) motif in the viral protein Gag-p6 and the cellular endosomal sorting factor Tsg101. In an effort to develop competitive inhibitors of this interaction, an SAR study was conducted based on the application of post solid-phase oxime formation involving the sequential insertion of aminooxy-containing residues within a nonamer parent peptide followed by reaction with libraries of aldehydes. Approximately 15–20-fold enhancement in binding affinity was achieved by this approach.

Keywords: aldehydes, combinatorial chemistry, oximes, peptidomimetics, Tsg101

Introduction

Chemical modulation of protein–protein interactions can offer potential new approaches to therapeutic development.[1–5] However, designing binding antagonists starting from peptides and peptide mimetics modeled on consensus recognition sequences may suffer from a lack of detailed solution NMR or X-ray crystallographic data.[6–11] Where the binding interactions of amino acid residues with the target protein are not known, a stepwise structural exploration along the ligand backbone can be undertaken. One way to achieve this is by inserting at discrete points, amino acids such as L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid that contain latent reactive handles amenable to library elaboration following the conclusion of peptide synthesis.[12] This tactic of delayed diversification allows a more facile generation of libraries than would be possible by constructing the peptides using collections of individually preformed amino acids. To facilitate this type of peptide modification, we have recently prepared orthogonally protected hydrazide and aminooxy-containing α-amino acids that can be incorporated into peptides using standard solid-phase Fmoc chemistries. Subsequent post solid-phase library diversification can be achieved by reaction with collections of aldehydes.[13–15]

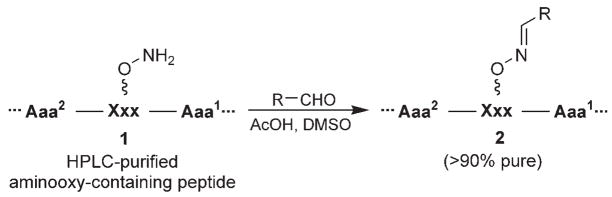

In the current paper, we extend this approach by sequentially examining each residue of a target peptide via a library of oxime derivatives. This is achieved through the initial solid-phase synthesis of a series of peptides in which each amino acid of the parent sequence is replaced by one or more aminooxy-containing residues. Following cleavage of the peptides from the resin and HPLC purification, each aminooxy-containing peptide (1, Scheme 1) is reacted individually with a range of aldehydes to yield libraries consisting of functionalized oximes appended from the peptide backbone by tethers of various length. We have found that the resulting peptide libraries (2) are sufficiently pure (>90 %) for direct biological evaluation.

Scheme 1.

Oxime-based library approach.

Viral budding represents a promising but unexploited process for antiretroviral inhibitors.[16–18] In order to examine a residue-by-residue oxime library scan on a potentially important peptide target, we focused our attention on a critical sequence involved with the budding of HIV-1. In the case of HIV-1, budding requires a direct interaction between a Pro-Thr-Ala-Pro (“PTAP”) motif in the viral protein Gag-p6 and the cellular endosomal sorting factor Tsg101.[19] Inhibition of this Gag-Tsg101 interaction may provide the basis for a new class of AIDS therapies.[17, 20] Tsg101 binding data for a series of peptides containing the “PTAP” sequence showed that the nonamer sequence “P1E2P3T4A5P6P7E8E9” retains modest binding affinity (Kd ~ 50–60 μm).[21] NMR solution studies of a “PEPTAPPEE” peptide binding to Tsg101 have indicated accommodation of the A5P6 side chains within a distinct pocket.[22, 23] This suggested recognition features shared by SH3 and WW domains for proline residues.[24] However, replacement of the key proline residue with N-alkylglycines (“peptoids”) or related constructs[13] did not increase binding affinity to the extent expected based on literature precedence.[25] Replacing the A5 residue with a variety of amino acids also failed to significantly improve binding affinity.[26] The ambiguous nature of the binding interactions of the parent nonamer supported the undertaking of a systematic examination of each residue using an oxime library approach.

Results and Discussion

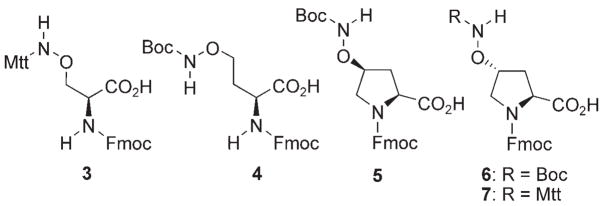

The protected aminooxy-containing amino acid analogues 3–7[14, 15] (Scheme 2) were used to prepare twelve parent peptides (8–19, Table 1) by standard solid-phase Fmoc chemistries. Replacement of T4 was by 3-aminooxy-Ala (3); glutamic acid residues were replaced using 4-aminooxy-aminobutyric acid (4), and proline residues were replaced using the 4-aminooxy-Pro derivatives 5–7 as indicated in Table 1. The A5 residue was left unaltered.[26] In order to facilitate binding analysis using fluorescence anisotropy, the N terminus of each peptide was labeled with fluoresceine isothiocyanate linked by a 5-aminovaleric acid spacer (FITC-Ava-).[13] For the HPLC purified parent aminooxy-containing peptides (8–19), a library of oxime derivatives was generated by reacting with a series of commercially obtained aldehydes (a–l, Table 2). The resulting oxime-containing peptides were sufficiently pure (>90 %) for direct Tsg101 binding studies as summarized in Table 2.

Scheme 2.

Protected aminooxy-containing amino acid reagents.

Table 1.

Aminooxy-containing parent peptides.a

| No | Peptide sequence | Aminooxy-Residueb |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | trans-4-aminooxy-Pro (6) |

| 9 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | cis-4-aminooxy-Pro (5) |

| 10 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | 4-aminooxy-Abu (4) |

| 11 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | trans-4-aminooxy-Pro (6) |

| 12 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | cis-4-aminooxy-Pro (5) |

| 13 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | 3-aminooxy-Ala (3) |

| 14 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | trans-4-aminooxy-Pro (6) |

| 15 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | cis-4-aminooxy-Pro (5) |

| 16 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | trans-4-aminooxy-Pro (6) |

| 17 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | cis-4-aminooxy-Pro (5) |

| 18 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | 4-aminooxy-Abu (4) |

| 19 | FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE | 4-aminooxy-Abu (4) |

Bold underlined indicates residue replaced by aminooxy-containing surrogate.

Protected reagent used to insert the aminooxy-containing residue.

Table 2.

| Modified residue parent peptide | P1 | E2 | P3 | T4 | (A5)P6 | P7[c] | E8 | E9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | ||

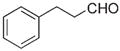

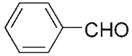

| – | Aldehyded (no aldehyde) | 37 | 56 | 22 | 68 | 214 | 64 | n.b. e | n.b. | 43 | 55 | 47 | 79 |

| a |

|

45 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 88 | 246 | n.b. | n.b. | 41 | 42 | 28 | 132 |

| b |

|

53 | 62 | 15 | 92 | 188 | n.f.f | n.b. | n.b. | 27 | 75 | 28 | 56 |

| c |

|

50 | 42 | 19 | 34 | 24 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 26 | 83 | 18 | 77 |

| d |

|

45 | 44 | 20 | 42 | 16 | 400 | n.b. | n.b. | 30 | 48 | 25 | 78 |

| e |

|

38 | 19 | 29 | 33 | 16 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 26 | 64 | 23 | 88 |

| f |

|

54 | 14 | 39 | 51 | 15 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 13 | 58 | 26 | 107 |

| g |

|

35 | 105 | 17 | 19 | 58 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 17 | 42 | 13 | 124 |

| h |

|

41 | 74 | 16 | 17 | 156 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 21 | 91 | 28 | 82 |

| i |

|

18 | 23 | 11 | 27 | 71 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 16 | 93 | 18 | 89 |

| j |

|

42 | 38 | 21 | 3.3 | 121 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 16 | 114 | 20 | 54 |

| k |

|

42 | 20 | 27 | 46 | 177 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 32 | 139 | 21 | 33 |

| l |

|

54 | 23 | 26 | 9.5 | 87 | n.f. | n.b. | n.b. | 30 | 54.5 | 35 | 55 |

Numerical data represent Kd values [μm] obtained as indicated in ref. [13].

Wild-type peptide FITC-Ava-PEPTAPPEE-amide Kd ~ 50–60 μm.

Data previously reported in ref. [14].

Aldehyde used to form the indicated oxime-containing peptide.

n.b.= no binding.

n.f. = no fit, suggesting weak binding (Kd > 500 μm).

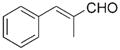

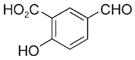

All parent peptides having free unreacted aminooxy groups, (except 14 and 15, which involved replacement of the critical P6 residue) retained binding affinities similar to the wild-type nonamer. This indicated that introduction of the aminooxy groups did not significantly disrupt native binding interactions and that the aminooxy-containing peptides provided suitable platforms for further SAR studies. Peptides 11 and 12, having trans and cis substituted 4-aminooxy-proline residues at the P3 position, showed markedly different Kd values (68 μm and 214 μm, respectively). Oxime scans of these two peptides (11 a–l and 12 a–l) provided a wide range of binding affinities. Peptide 11 j (Kd = 3.3 μm) exhibited a binding enhancement of 15–20 fold relative to the wild-type peptide (Kd ~ 50–60 μm). In contrast, the P6 position was intolerant to modification. Both the parent aminooxy peptides 14 and 15 as well as all oxime derivatives 14 a–l and 15 a–l, exhibited significantly diminished binding affinities. These results are consistent with our finding that modification of the P6 pyrrolidine ring by insertion of F, N, or O substituents adversely affects binding.[27]

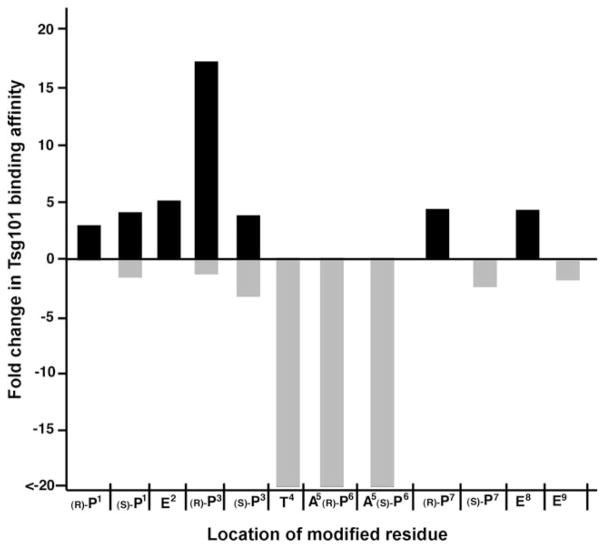

Although replacement of T4 with an unsubstitued aminooxy-containing residue (peptide 13, Kd = 64 μm) retained the binding affinity of the parent wild-type nonamer, further modification by oxime derivatization (peptides 13 a–13 l) decreased the binding affinity. This potentially indicates that a free amino or hydroxyl group is needed at this site, possibly to serve as a hydrogen-bond donor. The positions P1 (8a–l and 9 a–l), E2 (10 a–l), P7 (16 a–l), and E8 (18 a–l) were relatively insensitive to structural modifications. However, in some cases up to fivefold binding enhancement could be achieved (for example, 9 f, 10 i, 16 f, 16 i, 16 j, 18 c, 18 g, and 18 i). Interestingly, both of the parent peptides 16 and 17 having unsubstituted trans and cis 4-aminooxyproline-residues at the P7 position, exhibited similar binding affinities (43 μm and 55 μm, respectively), yet only oxime deriviatives of 16 resulted in higher affinity. Modification of 17 did not benefit binding. Changes at the E9 position (19 a–l) also had little effect on binding. These data are summarized graphically in Figure 1 as fold change in Tsg101 binding affinity.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of maximum effects on Tsg101 binding affinity achieved by modification of each residue of the wild-type sequence.

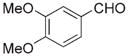

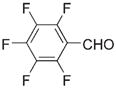

As the 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl oxime-containing peptide 11j showed a 15–20-fold binding enhancement relative to the wild-type nonamer sequence, a more focused library was prepared by reacting 11 with ten benzaldehydes containing one or more hydroxyl or methoxyl groups.[28] It was found that although 3-methoxy substituents contributed more to binding enhancement than 4-methoxy substituents, the original 3,4-dimethoxy-containing 11 j exhibited the highest affinity of the series.

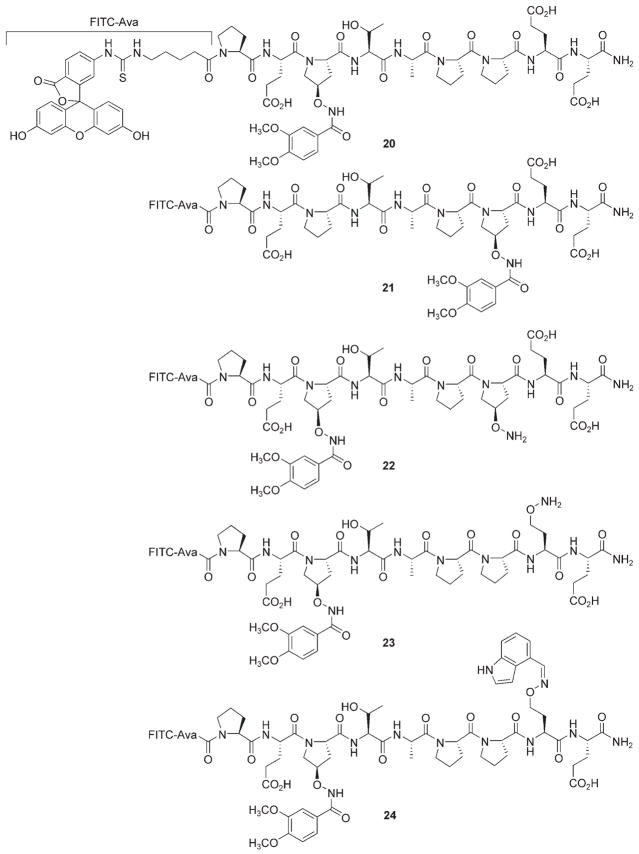

Using 11j as a starting point, the P7 and E8 sites were chosen for secondary modification. This was based on the fact that these locations were among the farthest removed from P3, the site of oxime derivatization in 11 j. In order to withstand the 90 % TFA conditions necessary to cleave peptides from the solid-phase resin, the P3 oxime bond in 11 j was replaced by an amide bond to yield peptide 20 (Scheme 3). This was accomplished using methyltrityl-protected reagent 7, which was deprotected on the resin and acylated with 3,4-dimethoxybenoic acid active ester. A similar hydrolytically stable version of 16 j (peptide 21) was prepared.

Scheme 3.

Structures of Tsg101-binding peptides.

Both 20 and 21 exhibited an approximately threefold loss of binding affinity relative to their parent oximes (20, Kd = 9 μm; 21, Kd = 41 μm). Bis-aminooxy-containing peptides 22 and 23 were prepared (Kd = 8.9 μm and 12 μm, respectively) and oxime libraries were generated from a selection of aldehydes determined by previous oxime binding data. Most of these “bi-modified” peptides exhibited a slight increase in binding affinity, with peptide 24 showing the greatest increase (Kd = 3.1 μm; fourfold relative to 23).[29]

Conclusions

In summary, an SAR study was conducted based on the application of post solid-phase oxime formation and utilizing aminooxy-containing residues substituted in a nonamer parent peptide. Approximately 15–20-fold enhancement in binding affinity was achieved by this approach. The methodology may be broadly applicable for peptide ligand optimization, especially in the early stages of SAR development where a three-dimensional knowledge of protein–ligand interactions is lacking.

Experimental Section

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized using commercially available Fmoc protected proline derivatives. Peptides were synthesized on NovaSyn®TGR resin (purchased from Novabiochem, cat. no. 01–64–0060) using standard Fmoc solid-phase protocols. 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) and N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) were used as coupling reagents for primary amines (single coupling, 2 h); Except as noted below, bromo-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBroP) was used for coupling of secondary amines (double coupling, 2 h). Coupling of Fmoc-trans-4-hydroxyproline-OH, Fmoc-cis-4-hydroxyproline-OH and Fmoc-trans-3-hydroxyproline-OH was conducted by using 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and HOBT (single coupling, 2 h); followed by masking the hydroxyl group with trityl chloride (TrtCl) (10 equiv) and DIPEA (12 equiv) in DCM/DMF (1:1) at RT (repeated once, 1 h each). The final coupling step was conducted using fluoresceine isothiocyanate (5.0 equiv) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (5.0 equiv) in NMP (overnight). The resin was washed (DMF, MeOH, DCM and Et2O) then dried under vacuum (overnight). Peptides were cleaved from the resin (200 mg) by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid/triisobutylsilane/H2O (90:5:5; 5 mL, 4 h). The resin was removed by filtration and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum, then precipitated with Et2O, and the precipitate was washed with Et2O. The resulting solid was dissolved in 50% aqueous acetonitrile (5 mL) and purified by reversed-phase preparative HPLC using a Phenomenex C18 column (21 mm Ø 0 250 mm, cat. no: 00G-4436-P0) with a linear gradient from 0 % aqueous acetonitrile (0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid) to 80% acetonitrile (0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid) over 35 min (flow rate of 10.0 mL min−1, detection at 220 nm). Lyophilization provided products as yellow powders.

Post solid-phase diversification

A mixture of HPLC-purified aminooxy-proline containing peptide (8–19; 15 mμm in DMSO, 10 μmL), aldehdye (a–l; 15 mμm in DMSO, 10 μmL), and acetic acid (70 μm in DMSO, 10 μmL) was gently agitated at room temperature (overnight). Examination by HPLC showed the reactions had gone to completion to produce oxime products in higher than 90% purity. Crude reaction mixtures were used directly for biological evaluation.

Acknowledgments

The Work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Center for Cancer Research, NCI-Frederick, and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, neither does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Loregian A, Marsden HS, Palu G. Rev Med Virol. 2002;12:239–262. doi: 10.1002/rmv.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loregian A, Palu G. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:750–762. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arkin M. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chène P. Chem Med Chem. 2006;1:400–411. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells JA, McClendon CL. Nature. 2007;450:1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kritzer JA, Stephens OM, Guarracino DA, Reznik SK, Schepartz A. Bio org Med Chem. 2004;12:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sillerud LO, Larson RS. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6:151–169. doi: 10.2174/1389203053545462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond MC, Harris BZ, Lim WA, Bartlett PA. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1247–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Li C, Ke S, Satyanarayanajois SD. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4038–4047. doi: 10.1021/jm0700868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieddu E, Pasa S. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:21–32. doi: 10.2174/156802607779318271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadowsky JD, Fairlie WD, Hadley EB, Lee HS, Umezawa N, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Wang S, Huang DCS, Tomita Y, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:139–154. doi: 10.1021/ja0662523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Nandy SK, Lawrence DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3394–3395. doi: 10.1021/ja037300b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F, Stephen AG, Adamson CS, Gousset K, Aman MJ, Freed EO, Fisher RJ, Burke TR., Jr Org Lett. 2006;8:5165–5168. doi: 10.1021/ol0622211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu F, Stephen AG, Fisher RJ, Burke TR., Jr Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1096–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Thomas J, Burke TR., Jr Synthesis. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turpin JA. Exp Rev Anti-Infective Ther. 2003;1:97–128. doi: 10.1586/14787210.1.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shehu-Xhilaga M, Ablan S, Demirov DG, Chen C, Montelaro RC, Freed EO. J Virol. 2004;78:724–732. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.724-732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinger PP, Schubert U. Exp Rev Anti-Infective Ther. 2005;3:61–79. doi: 10.1586/14787210.3.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrus JE, von Schwedler UK, Pornillos OW, Morham SG, Zavitz KH, Wang HE, Wettstein DA, Stray KM, Côté M, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Sundquist WI. Cell. 2001;107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demirov DG, Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:955–960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032511899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.See Supporting Information I.

- 22.Pornillos O, Alam SL, Davis DR, Sundquist WI. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2002;9:812–817. doi: 10.1038/nsb856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pornillos O, Alam SL, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Davis DR, Sundquist WI. EMBO J. 2002;21:2397–2406. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freed EO. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:56–59. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen JT, Turck CW, Cohen FE, Zuckermann RN, Lim WA. Science. 1998;282:2088–2092. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.See Supporting Information II.

- 27.See Supporting Information III.

- 28.See Supporting Information IV.

- 29.See Supporting Information V.