Abstract

Recent failures in efforts to develop an effective vaccine against HIV-1 infection have emphasized the importance of antiretroviral therapy in treating HIV-1-infected patients. Thus far, inhibitors of two viral enzymes, reverse transcriptase and protease, have had a profoundly positive impact on the survival of HIV-1-infected patients. However, new inhibitors that act at diverse steps in the viral replication cycle are urgently needed because of the development of resistance to currently available antiretrovirals. This review summarizes recent progress in antiretroviral drug discovery and development by specifically focusing on novel inhibitors of three phases of replication: viral entry, integration of the viral DNA into the host cell genome and virus particle maturation.

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), the primary causative agent of AIDS, is an important human pathogen, infecting more than 40 million people [1]. There is currently no effective vaccine or cure, although the introduction of antiretroviral drugs has significantly improved the prognosis for infected individuals with access to treatment. However, the emergence of drug-resistant virus isolates is having an increasingly detrimental impact on treatment options and disease outcome, making the identification and development of new drugs, targeting novel sites of action, a high research priority.

A key biological property of HIV-1 that facilitates the emergence of drug resistance is its capacity to evolve rapidly, resulting in extensive genetic diversity [2]. Two factors are primarily responsible for the ability of HIV-1 to generate this high degree of genetic variability: the error-prone nature of the HIV-1 polymerase (the reverse transcriptase (RT)) and the rapid rate of HIV-1 replication [2]. The rate of virus evolution is also significantly elevated by recombination events during reverse transcription [3,4]. Recombination events can accelerate the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV-1 isolates [3,4].

The generation of HIV-1 genetic variation results in a diverse but related viral population, termed quasi-species, which contains a large number of potentially drug-resistant variants [5]. However, it is the presence of antiretroviral drugs, particularly at suboptimal concentrations, which exerts a positive selection pressure for the expansion of drug-resistant viral isolates. In vitro, suboptimal drug concentrations are deliberately used to generate drug-resistant HIV-1 isolates for study, whereas In vivo a primary cause of resistance development is patient nonadherence to complex and often-toxic multidrug regimens [6,7]. Currently, the most widely used regimen, referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), combines three or four drugs that act against two viral enzymes [6,7]. Typically, HAART combines two classes of drugs active against RT (the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)) with drugs that target the viral protease (PR). Although HAART has been shown successfully to suppress viral loads for years at a time, the virus is not eradicated and persists in latent reservoirs [8,9]. These reservoirs can serve to replenish the main pool of replicating virus, allowing continued virus evolution and acquisition of resistance.

The emergence and transmission of MDR HIV-1 isolates has serious clinical implications, generating a profound need for new antiretroviral drugs that are effective against these highly resistant virus isolates. Ideally, new drugs should target steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle that are not blocked by the antiretroviral drugs currently in widespread use (i.e. the RT and PR inhibitors). Three alternative steps in HIV-1 replication – virus entry, integration and maturation – are currently the focus for the development of new antiretroviral drugs. Here we review drugs from these new classes of antiretrovirals that have recently been approved for clinical use, together with some of the most promising drug candidates currently undergoing preclinical and clinical development. A particular emphasis will be placed on mechanisms by which resistance to these new drugs develops as this knowledge is valuable in (i) confirming drug efficacy, (ii) elucidating the drugs’ target and mechanism of action and (iii) predicting the likelihood and type of resistance that may arise in treated patients [10].

Entry inhibitors

New therapeutics targeting HIV-1 entry are among the most recent additions to the current arsenal of anti-HIV-1 agents. In addition to the myriad of new therapeutic candidates in preclinical and clinical development [11–18], two drugs have been approved for clinical use: the fusion inhibitor T20 (enfuvirtide, fuzeon or DP178) was approved in 2003 [19] and in 2007 the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc (selzentry) was approved for restricted clinical use in the US (http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01677.html)(Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibitors discussed in detail in the text

| Inhibitor | Target | Status of clinical development | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Enfuvirtide (T-20, fuzeon) |

Fusion/entry (gp41) |

FDA-approved |

Ac-YTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELLFLDKWASLWNWF-NH2 |

|

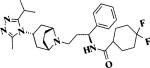

Maraviroc |

Fusion/entry (CCR5) |

FDA-approved |

|

|

Vicriviroc |

Fusion/entry (CCR5) |

Phase III |

|

|

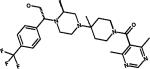

Raltegravir (MK-0518) |

Integrase strand transfer |

FDA-approved |

|

|

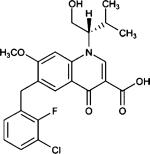

Elvitegravir (JTK-303, GS9137) |

Integrase strand transfer |

Phase II completed |

|

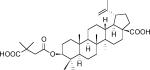

| Bevirimat (PA-457, DSB) | Maturation | Phase II |  |

Entry of HIV-1 into the host cell is essential for the virus to establish a productive infection and, therefore, represents a major target for preventing HIV-1 infection and transmission. Successful development of the entry step as a therapeutic target has been driven by basic research on the molecular mechanisms involved in virus entry. The central event in the entry process is the fusion between viral and cellular membranes, which delivers the viral genome into the target cell. The viral component that orchestrates the fusion process is the envelope (Env) glycoprotein complex, the active form of which is composed of a heterotrimer containing three molecules each of the surface glycoprotein gp120 and the transmembrane glycoprotein gp41.

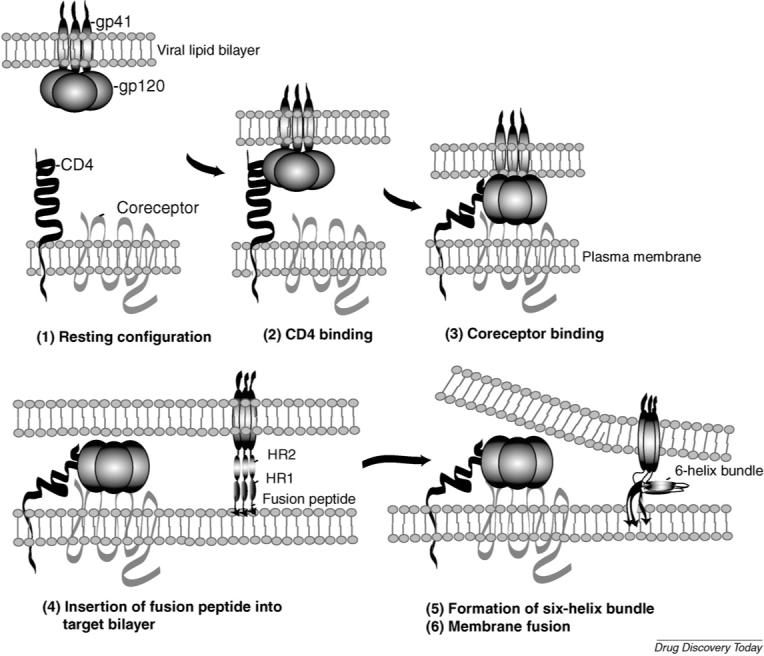

Env-mediated membrane fusion is a sequential, multistep process, which has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [15,20,21] (Fig. 1). Briefly, gp120 first binds to the cellular receptor CD4, thereby triggering conformational changes in gp120 that allow it to interact with a coreceptor. The predominant coreceptors used In vivo are CCR5 and CXCR4, which normally function as chemokine receptors [15,18,22]. Different HIV-1 strains have different tropisms, depending on which coreceptor they utilize; viruses that use CCR5 (‘R5’ strains) typically infect macrophages and primary T-cells and are usually the virus isolates that are transmitted between individuals. HIV-1 strains that use CXCR4 (‘X4’ strains) infect T-cells but not macrophages and tend to evolve years after infection and are often associated with rapid disease progression. Dual-tropic (‘R5X4’) viruses can use both coreceptors. Coreceptor binding triggers a second conformational rearrangement, which allows insertion of the hydrophobic fusion domain at the N-terminus of gp41 into the target cell membrane. Each of the three gp41 molecules then folds upon itself to form a six-helix bundle, which brings the viral and cellular membranes into close proximity. Two heptad repeats (HR1 and HR2) in the ectodomain of gp41 are required for the formation of the six-helix bundle and thus play an essential role in the fusion process.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic depiction of Env-mediated membrane fusion. (1) The Env complex (gp120 and gp41), CD4 and coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) before Env/CD4 engagement. The viral membrane is at the top and the target cell membrane at the bottom. (2) gp120 binding to CD4. (3) Interaction between gp120 and coreceptor after CD4 binding. (4) Conformational changes in gp120 and gp41 triggered by CD4 and coreceptor engagement induce gp41 to extend and insert the N-terminal fusion peptide into the target cell membrane. In this conformation, the heptat repeats 1 and 2 (HR1 and HR2) are extended in a rod-like fashion. (5 and 6) HR1 and HR2 form a six-helix bundle and membrane fusion takes place. Peptides derived from HR1 or HR2 (e.g. T20) prevent six-helix bundle formation. Reprinted with permission from Freed and Martin [94] (5th Edition, Chapter 57).

Because each step of the viral entry pathway is a potential target for antiviral agents, entry inhibitors fall into several categories depending on which step they block. Major classes include: (i) CD4-gp120-binding inhibitors, (ii) CCR5- or CXCR4-based inhibitors and (iii) fusion inhibitors. The most clinically advanced entry inhibitor is T20, a fusion inhibitor, which has been shown to potently inhibit virus replication both In vitro and In vivo [21]. T20 is a 36-amino-acid synthetic peptide, the sequence of which is derived from the gp41 HR2 [23] (Table 1). T20 is thought to block the fusion process by binding to HR1, thereby competitively inhibiting the HR1/HR2 interaction and blocking six-helix bundle formation [24–26]. By binding HR1, T20 targets a transient structural intermediate in the fusion process. Elucidation of the mechanism of action of T20 was assisted by the In vitro selection of T20-resistant viral isolates [27]. Mutations conferring resistance to T20 mapped to three amino acid residues within HR1 (Gly-Ile-Val at gp41 positions 36−38). Binding studies showed that protein fragments composed of HR1 that contained T20-resistance-conferring mutations no longer bound T20. Consistent with In vitro selection experiments, clinical studies have shown that the HR1 region of gp41 between amino acids 36 and 45 (GIVQQQNNLL) is of central importance for the development of T20 resistance [21,28]. Residues in HR2 have also been reported to contribute to T20 susceptibility, probably by acting as secondary or compensatory mutations to changes in HR1 [29]. T20 susceptibility has also been associated with mutations in gp120 that affect receptor engagement and rates of membrane fusion, resulting in a reduction in the time period that the T20-binding site is exposed and hence sensitivity to T20 [30,31].

Overall, T20 is considered to be a drug with a low genetic barrier for resistance development, despite the conserved nature of the gp41 HR1 region. Other limitations associated with T20 treatment include the high cost of the peptide manufacturing process, and its mode of delivery, which entails twice-daily subcutaneous injection [32]. An extensive research effort is currently underway to identify improved peptide or new small molecule fusion inhibitors with superior anti-HIV activity, increased bioavailability and reduced production costs [16].

Another strategy under development to inhibit HIV-1 entry is aimed at blocking the interaction between gp120 and the CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptors [12,14,20,33,34]. Molecules in this group of inhibitors are primarily being designed to target the cellular rather than the viral component of the interaction. The rationale for targeting CCR5 stems from the observation that a defective form of the CCR5 gene with a 32-base-pair deletion (CCRD32) protects homozygous individuals from infection with R5 strains of HIV-1 and heterozygous individuals from rapid disease progression. The CCRD32 allele does not appear to be accompanied by severe adverse health effects, suggesting that CCR5-targeted therapies would be well tolerated. The finding that CXCR4 knockout mice suffer from a variety of severe disorders suggests that drugs targeting CXCR4 may be less well tolerated compared with CCR5-based inhibitors. Indeed, although several CXCR4 inhibitors potently block HIV-1 infection In vitro, their preclinical development has not generally advanced because of adverse effects.

At present one CCR5 inhibitor, maraviroc, has been approved for clinical use. Several others are currently in preclinical and clinical development, including vicriviroc (Table 1), which recently entered phase III clinical trials [12,14,15,18,20,33]. Both maraviroc and vicriviroc are small molecules that bind CCR5, preventing its interaction with gp120 [35,36]. By specifically targeting CCR5 they do not inhibit X4- or R5X4-tropic viral isolates [35,36]. Hence, FDA approval of maraviroc stipulates that it is used as therapy for treatment-experienced adult patients in which only R5-tropic HIV-1 is detectable (http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01677.html). This baseline coreceptor screening is required because there is considerable concern about the clinical consequences of selection and/or expansion of X4-tropic viruses [22,37]. A study monitoring viral tropism in patients enrolled in a ten-day maraviroc mono-therapy study concluded that rare X4 variants probably emerged by outgrowth of a pretreatment X4 reservoir, rather than R5-tropic clones evolving the ability to switch coreceptor use to CXCR4 [38]. The consensus of In vitro selection studies is that the development of resistance to CCR5-based inhibitors generally does not involve coreceptor switching to CXCR4 use but instead arises by the virus retaining the use of CCR5 even though CXCR4 remains available [39–42]. Indeed, In vitro selection of maraviroc-resistant isolates documented continued reliance on CCR5 while maraviroc was still bound to CCR5 [39]. However, several studies have reported coreceptor switching to occur under selection pressure from CCR5 and CXCR4 inhibitors [42–45]. The height of the genetic barrier to coreceptor switching may depend on the HIV-1 isolate, as some strains only require a few amino acid changes to undergo a coreceptor switch [43,46,47], whereas others require the accumulation of several mutations [48]. More extensive studies on the mechanisms of resistance development to coreceptor-based inhibitors will be essential as this promising group of therapeutics moves into the clinic.

Inhibitors targeting the initial CD4-gp120-binding step of the entry process are also being investigated [11–13,49]. A variety of different candidate molecules with different mechanisms of action have been studied. These include PRO-542, a soluble fusion protein that mimics the CD4 receptor; TNX-355, a monoclonal antibody directed against CD4; and small molecules such as BMS-378806 and BMS-488043, which bind gp120 primarily interfering with its ability to bind CD4, although an alternative mechanism of action not attributed to inhibited CD4 binding has also been proposed. To date, none of these compounds have progressed into the clinic, although initial In vivo studies have been performed. Recently, two exciting new classes of entry inhibitor have been reported. First, a natural peptide was discovered from human hemofiltrate and then optimized for increased anti-HIV potency [50]. Uniquely, this inhibitor targets the gp41 fusion peptide and, encouragingly, preliminary attempts to isolate resistant viruses In vitro proved difficult [50]. Second, a cholesterol-binding compound, amphotericin B methyl ester (AME), has been reported to inhibit potently HIV entry In vitro [51]. Interestingly, a novel mechanism of resistance was revealed by In vitro selection in the presence of AME [52]. Resistance was conferred by single amino acid substitutions in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 that introduced a cleavage site for the HIV-1 PR into gp41. This PR-mediated cleavage of the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 caused the tail to be removed after Env incorporation into virions, thereby activating Env fusogenicity and inducing AME resistance. It is intriguing that truncation of the transmembrane Env protein by PR in response to AME mimics a strategy used by other retroviruses to activate Env function [52].

Integrase inhibitors

Major successes have been achieved in the development and clinical use of drugs that inhibit the HIV-1 RT and PR enzymes. HIV-1 encodes a third enzyme, integrase (IN), which is currently the focus of an intense research effort to develop new anti-HIV-1 drugs [53–57]. This research effort was validated in 2007 by the FDA approval of the first IN inhibitor for clinical use, MK-0518 (raltegravir) (http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01726.html). A second compound, GS-9137 (JTK-303, elvitegravir), is also performing well in clinical trials [58] (Table 1).

IN catalyzes the integration of HIV-1 viral DNA into the host cell genome. The integrated viral DNA, termed the provirus, serves as the template for viral RNA synthesis and is maintained as a part of the host cell genome for the lifetime of the infected cell. Integration is an essential step in the HIV-1 life cycle, making IN a viable drug target. The IN protein is composed of three structural domains: an N-terminal and a C-terminal domain, and a central catalytic domain. The catalytic domain contains an essential catalytic triad, composed of residues D64, D166 and E152, known as the DDE motif [53].

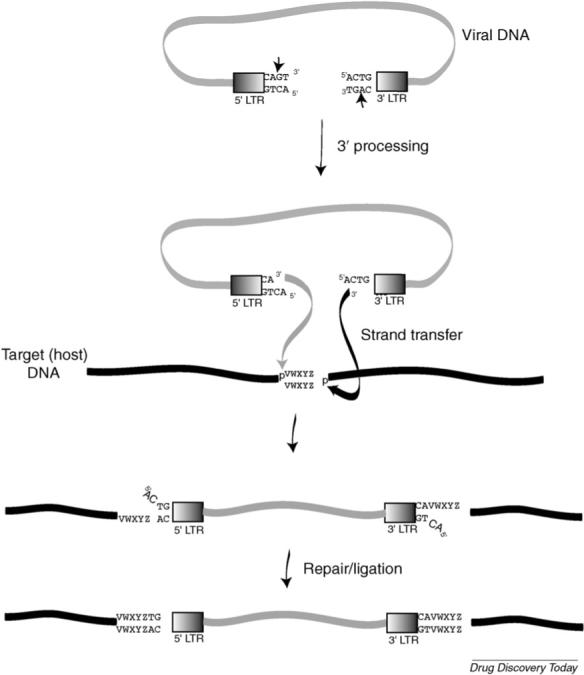

Integration is a complex multistep process with two distinct reactions catalyzed by IN: (i) 3′-processing (3′P) and (ii) strand transfer (ST) (reviewed elsewhere [53,54,59])(Fig. 2). Briefly, 3′P occurs in the cytoplasm following conversion of the viral RNA genome into viral DNA by RT. IN recognizes specific sequences in the long terminal repeats (LTRs) of the viral DNA and, in the case of most retroviruses, performs a site-specific endonucleolytic cleavage reaction adjacent to a CA dinucleotide. This endonuclease reaction results in the removal of two (or occasionally three) nucleotides from each 3′ end of the viral DNA, producing new 3′-hydroxyl ends (CA–OH-3′) that are recessed by two nucleotides. Following 3′P, IN remains bound to the viral DNA as a part of a high-molecular-weight preintegration complex (PIC), which is transported through the nuclear pore complex into the nucleus where IN catalyzes the ST reaction. ST results in the insertion of the processed viral DNA ends into the chromosomal DNA. This insertion is a transesterification reaction, which involves a staggered cleavage of 4−6 bp in the target (host) DNA and the joining of processed CA–OH-3′ viral DNA to the 5′-phosphate ends of the host DNA. Both the 3′P and ST reactions require divalent metal-ion cofactors (Mg2+ or Mn2+) whose binding in the catalytic active site of IN is mediated by the catalytic DDE motif. The ST reaction produces a gapped intermediate which is repaired by host cell enzymes, perhaps in conjunction with IN, to complete the integration process.

FIGURE 2.

Integration pathway. The IN enzyme cleaves the viral DNA ends after a CA dinucleotide (3′ processing) and integration occurs in the nucleus (strand transfer). Viral DNA integration leads to a signature duplication of a short stretch of cellular DNA, represented as ‘VWXYZ’. After integration, cellular enzymes repair and ligate the viral/cellular DNA junction. Reprinted with permission from Freed and Martin [94] (5th Edition, Chapter 57).

IN inhibitor development has lagged behind that of HIV-1 RT and PR inhibitors as many of the early inhibitors lacked specificity and/or were highly toxic when tested in cells [56]. Significant progress was achieved with the development of an assay that identified compounds that specifically inhibited ST [56], aiding the discovery of a series of related inhibitors including the lead compounds MK-0518 and GS-9137. These lead compounds have been shown to inhibit potently HIV-1 integration at nanomolar concentrations In vitro [60–65] and block HIV-1 replication In vivo [58,66–69]. The functional commonality shared by this family of compounds is a diketo acid or structurally related derivative, with a diketo or diketo-like group linking a coplanar acid group and an aromatic group. The clinically effective compounds MK-0158 and GS-9137 are derivatives of this basic structure and contain functional hydroxypyrimidinone carboxamide and quinolone groups, respectively (Table 1). The chemical development of IN inhibitors has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [53–57].

The mechanism of selective ST inhibition has been elucidated by several key experimental observations. The first significant observation was obtained by a crystal structure of the inhibitor 5-CITEP in complex with the catalytic core of IN [61]. In this structure, the inhibitor was bound in the center of the catalytic active site, lying between the three residues of the DDE motif without displacing the metal ions [61]. The next key observation was that inhibitor binding required a catalytically active IN assembled on viral DNA ends. Target (host chromosomal) DNA substrates that are competent for ST are effective competitors of inhibitor binding, suggesting that the host DNA and inhibitor occupy similar sites in the IN complex [70,71]. Further mechanistic insights were provided by experiments establishing that inhibitor binding and function are dependent on the metal-ion cofactors coordinated with the DDE motif [71,72]. Based on these key observations, interfacial inhibition has been hypothesized as a mechanism of action of selective ST inhibitors [54]. In this model it is proposed that the ST inhibitors preferentially bind a structural intermediate at the interface of the viral DNA-IN–divalent metal complex formed during the 3′P step. Upon inhibitor binding, the 3′P intermediate is stabilized, IN is unable to bind target chromosomal DNA and the ST reaction is unable to proceed [54].

Resistant mutants played an important role in defining the mechanism of action of ST transfer inhibitors. In vitro selection studies mapped the majority of resistance-conferring mutations to residues clustered around the IN catalytic active site (the DDE motif) [60,63,65,73,74]. The close proximity of resistance-conferring mutations to the enzyme's active site establishes IN as the target of viral inhibition. Resistance mutations also helped in determining the essential role of the divalent metal ions in ST inhibitor binding and function. Resistance was shown to be metal-dependent, with active-site mutants displaying resistance only when assays were performed in the presence of Mg2+. This metal-ion dependence implies that resistance involves effects on ion binding [71]. A substantial reduction in virus replication fitness in cell-based assays was observed for all resistance-conferring mutations [60,63,65,73,74], suggesting that a high genetic barrier to resistance may exist In vivo. However, recent studies have reported the emergence of a potential MK-0158-resistance-conferring mutation (N155H) in a rhesus macaque animal model [69]. The significance of this mutation was confirmed by preliminary resistance profiles from clinical trials evaluating MK-0158. These resistance data demonstrate three broad genetic pathways to resistance defined by key mutations at residues N155, Y143 or Q148 [66,75–77]. In vivo resistance profiles to GS-9137 contained mutations at residues E92, E138, Q148, N155, S147 and T66 [78,79]. In studies with both inhibitors a complex variety of other mutations, many of which overlap with resistance-conferring mutations selected In vitro, were also observed In vivo to enhance resistance and/or compensate for replication defects imposed by resistance-conferring mutations [66,69,75,76,78–80]. This complex array of secondary and/or compensatory mutations may be suggestive of a high genetic barrier to resistance, however data from the clinic are too preliminary for any definitive conclusions. Depending on the ST inhibitor derivative tested, varying degrees of cross-resistance to IN inhibitors have been reported [63,65,73,76,78–80]. The emergence of cross-resistance will have consequences for the future choices of clinical drug regimens if multiple IN inhibitors are approved for clinical use.

Maturation inhibitors

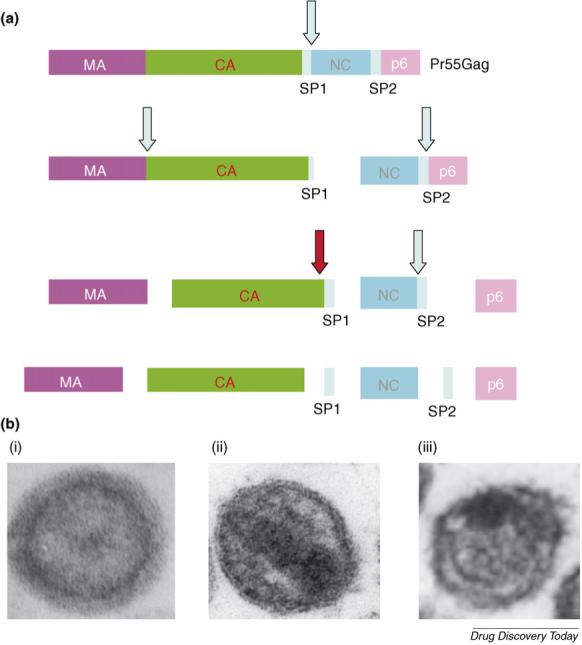

The assembly of HIV-1 particles is driven by the expression of the Gag precursor protein, Pr55Gag. At the plasma membrane, Gag assembles into a spherical particle that buds off from the surface of the infected cell [81,82]. Concomitant with virus budding, the viral PR cleaves Pr55Gag to generate the mature Gag proteins p17 (matrix or MA), p24 (capsid or CA), p7 (nucleocapsid or NC) and p6. Located between CA and NC and between NC and p6 are two small spacer peptides (SPs) known as SP1 and SP2, respectively (Fig. 3). PR-mediated cleavage of Pr55Gag and the GagPol polyprotein precursor Pr160GagPol leads to a structural rearrangement in viral Gag proteins and nucleic acid, a process known as maturation. During maturation, the immature virion, which contains an electron-lucent center, is converted to a mature virus particle containing an electron-dense, conical core (Fig. 3). The essential role of maturation in the virus replication cycle has made PR inhibitors highly effective antiretroviral agents, particularly when administered in combination with RT inhibitors. However, as with other antiretroviral therapies, resistance limits the efficacy of PR inhibitors in an ever-increasing number of patients.

FIGURE 3.

(a) HIV-1 Gag processing cascade, indicating the major Gag domains matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC), and p6 and spacer peptides SP1 and SP2. The order of processing events is depicted by vertical flow diagram, with arrows indicating sites of cleavage by PR. The red arrow denotes the cleavage event blocked by 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (PA-457 or bevirimat). (b) Immature HIV-1 particle showing ‘doughnut-like’ morphology (i); mature virion with condensed, conical core (ii); virion produced in the presence of bevirimat, showing aberrant core and crescent of electron density inside the viral lipid bilayer (iii).

One of the notable features of Gag processing is that it occurs as a highly ordered cascade of cleavage events. Several studies have demonstrated that disruption of the regulated nature of Gag processing is highly detrimental to virus maturation and infectivity [81,82]. These observations suggest that interfering with the ability of PR to cleave individual processing sites within Gag could constitute a viable approach to developing novel antiretroviral therapies. Indeed, this is the mechanism of action of 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (known variously as PA-457, DSB or bevirimat) [83–86] (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

An early study of the antiviral activity of bevirimat suggested that it blocked virus budding [87]. However, subsequent studies [84,85] showed clearly that this compound disrupts the processing of Gag at the CA–SP1 cleavage site, leading to the accumulation of the CA–SP1 processing intermediate. Virions produced from bevirimat-treated cells display an unusual ultrastructural morphology characterized by the formation of an electron-dense crescent under the virion lipid bilayer and a globular aggregate of electron density often acentrically positioned in the particle (Fig. 3).

Several additional lines of evidence support the hypothesis that the CA–SP1 junction is the target for bevirimat activity: (1) selection for viral variants that can replicate in the presence of bevirimat identified a series of mutations in a relatively small region (approximately ten amino acids) spanning the CA–SP1 cleavage site that conferred resistance to this compound [84,88,89]. (2) Mutations conferring resistance to bevirimat have not been observed in PR or at locations in Gag outside the CA–SP1 junction [89]. (3) The simian immunodeficiency virus from rhesus macaques (SIVmac) is inherently insensitive to bevirimat. This nonhuman primate lentivirus can be made sensitive to bevirimat by introducing a CA–SP1 fragment from HIV-1 into SIVmac [85]. (4) Mutations engineered into the CA–SP1 boundary region can confer resistance to bevirimat.

Although there is a significant amount of evidence to support the hypothesis that bevirimat targets the CA–SP1 junction (see above), the precise mechanism of action remains to be defined. The observation that bevirimat does not block the processing of purified Gag in solution [84] raised the possibility that the compound binds an assembled target. Indeed, binding of bevirimat to immature (uncleaved) viral particles can be detected, whereas PR-mediated Gag processing or mutations in the CA–SP1 boundary region ablate binding [90]. Furthermore, bevirimat was shown to block CA–SP1 processing In vitro when Gag self-assembled into VLPs but not in the absence of assembly [91]. Thus, the current working model for bevirimat activity posits that the compound binds a site at the CA–SP1 junction created by Gag assembly. The binding site is not present before assembly (i.e. on monomeric Gag) and Gag processing by PR destroys the binding site.

Based on the model for bevirimat activity described above, the most straightforward path to bevirimat resistance would involve the introduction of mutations in the CA–SP1 boundary region that block bevirimat binding. Indeed, bevirimat-resistance mutations have been observed to block compound binding to immature VLPs [92]. However, in some cases, resistant mutants still displayed a significant level of bevirimat binding [92] and resistant mutants that exhibit enhanced replication and maturation ability in the presence of bevirimat have been reported [89]. Thus, it appears that multiple mechanisms of resistance to this maturation inhibitor may be possible.

Bevirimat is currently undergoing phase II clinical testing [93]. Initial studies, which were conducted over a ten-day period of dosing in a small number of HIV-1-infected volunteers given single daily oral doses of bevirimat, showed reductions in viral loads of 1 log at the highest doses of the compound. Viral genotyping was performed before initiation of therapy and several weeks after the completion of the study. No mutations associated with resistance In vitro [89] were observed in the patient-derived sequences [93]. No significant adverse effects of the compound have been observed thus far. Ongoing follow-up trials will involve higher doses of bevirimat, administered for longer periods of time. Development of bevirimat-related compounds that may possess pharmacological properties superior to those of bevirimat, or that may be effective against bevirimat-resistant isolates, is underway [86]. Future efforts in the area of maturation inhibitor development will probably also focus on compounds structurally unrelated to bevirimat that block cleavage at the CA–SP1 junction or at other Gag processing sites.

Conclusion

The emergence and transmission of HIV-1 isolates resistant to existing antiretroviral drugs has serious clinical consequences and is the nemesis of sustained successful clinical treatment of HIV-1 patients. The development of resistance is therefore driving research to identify new drugs targeting novel steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle. Recent progress has been made in developing drugs targeting HIV-1 entry, integration and maturation. The addition of new drugs to the existing therapeutic arsenal will improve treatment options and clinical prospects particularly for those patients failing current drug regimens based primarily on combinations of RT and PR inhibitors. Despite the negative impact of drug resistance in the clinic, understanding resistance mechanisms provides a powerful tool to aid the discovery and development of new HIV-1 therapies.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic. UNAIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rambaut A, et al. The causes and consequences of HIV evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:52–61. doi: 10.1038/nrg1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu WS, et al. Retroviral recombination: review of genetic analyses. Front. Biosci. 2003;8:d143–d155. doi: 10.2741/940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Najera R, et al. Genetic recombination and its role in the development of the HIV-1 pandemic. AIDS. 2002;16(Suppl 4):S3–S16. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200216004-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson MM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 genetic forms and its significance for vaccine development and therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002;2:461–471. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LF, et al. Ten years of highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Med. J. Aust. 2007;186:146–151. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon V, et al. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Lancet. 2006;368:489–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69157-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lassen K, et al. The multifactorial nature of HIV-1 latency. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcello A. Latency: the hidden HIV-1 challenge. Retrovirology. 2006;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richman DD. Antiviral drug resistance. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rusconi S, et al. An update in the development of HIV entry inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:1273–1289. doi: 10.2174/156802607781212239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegert S, et al. Novel anti-viral therapy: drugs that block HIV entry at different target sites. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2006;6:557–562. doi: 10.2174/138955706776876267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briz V, et al. HIV entry inhibitors: mechanisms of action and resistance pathways. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:619–627. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsibris AM, Kuritzkes DR. Chemokine antagonists as therapeutics: focus on HIV-1. Annu. Rev. Med. 2007;58:445–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.080105.102908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Este JA, Telenti A. HIV entry inhibitors. Lancet. 2007;370:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu S, et al. HIV entry inhibitors targeting gp41: from polypeptides to small-molecule compounds. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007;13:143–162. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnegan C, Blumenthal R. Dissecting HIV fusion: identifying novel targets for entry inhibitors. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2006;6:355–367. doi: 10.2174/187152606779025851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas P, et al. Access denied? The status of co-receptor inhibition to counter HIV entry. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007;8:923–933. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson D. US FDA approves new class of HIV therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:470–471. doi: 10.1038/nbt0503-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierson TC, et al. Prospects of HIV-1 entry inhibitors as novel therapeutics. Rev. Med. Virol. 2004;14:255–270. doi: 10.1002/rmv.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg M, et al. HIV fusion and its inhibition in antiretroviral therapy. Rev. Med. Virol. 2004;14:321–337. doi: 10.1002/rmv.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger EA, et al. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wild CT, et al. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CH, et al. A molecular clasp in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 TM protein determines the anti-HIV activity of gp41 derivatives: implication for viral fusion. J. Virol. 1995;69:3771–3777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3771-3777.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furuta RA, et al. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilgore NR, et al. Direct evidence that C-peptide inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry bind to the gp41 N-helical domain in receptor-activated viral envelope. J. Virol. 2003;77:7669–7672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7669-7672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimsky LT, et al. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J. Virol. 1998;72:986–993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.986-993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg ML, Cammack N. Resistance to enfuvirtide, the first HIV fusion inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:333–340. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu L, et al. Emergence and evolution of enfuvirtide resistance following long-term therapy involves heptad repeat 2 mutations within gp41. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1113–1119. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1113-1119.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves JD, et al. Sensitivity of HIV-1 to entry inhibitors correlates with envelope/coreceptor affinity, receptor density, and fusion kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16249–16254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252469399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore JP, Doms RW. The entry of entry inhibitors: a fusion of science and medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:10598–10602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932511100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaBonte J, et al. Enfuvirtide. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:345–346. doi: 10.1038/nrd1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lederman MM, et al. Biology of CCR5 and its role in HIV infection and treatment. JAMA. 2006;296:815–826. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujii N, et al. The therapeutic potential of CXCR4 antagonists in the treatment of HIV. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003;12:185–195. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorr P, et al. Maraviroc (UK-427,857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4721–4732. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4721-4732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strizki JM, et al. Discovery and characterization of vicriviroc (SCH 417690), a CCR5 antagonist with potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4911–4919. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4911-4919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regoes RR, Bonhoeffer S. The HIV coreceptor switch: a population dynamical perspective. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westby M, et al. Emergence of CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variants in a minority of HIV-1-infected patients following treatment with the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc is from a pretreatment CXCR4-using virus reservoir. J. Virol. 2006;80:4909–4920. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4909-4920.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westby M, et al. Reduced maximal inhibition in phenotypic susceptibility assays indicates that viral strains resistant to the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc utilize inhibitor-bound receptor for entry. J. Virol. 2007;81:2359–2371. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02006-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trkola A, et al. HIV-1 escape from a small molecule, CCR5-specific entry inhibitor does not involve CXCR4 use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012519099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuhmann SE, et al. Genetic and phenotypic analyses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape from a small-molecule CCR5 inhibitor. J. Virol. 2004;78:2790–2807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2790-2807.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marozsan AJ, et al. Generation and properties of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate resistant to the small molecule CCR5 inhibitor, SCH-417690 (SCH-D). Virology. 2005;338:182–199. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosier DE, et al. Highly potent RANTES analogues either prevent CCR5-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vivo or rapidly select for CXCR4-using variants. J. Virol. 1999;73:3544–3550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3544-3550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Este JA, et al. Shift of clinical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from X4 to R5 and prevention of emergence of the syncytium-inducing phenotype by blockade of CXCR4. J. Virol. 1999;73:5577–5585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5577-5585.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulick RM, et al. Phase 2 study of the safety and efficacy of vicriviroc, a CCR5 inhibitor, in HIV-1-infected, treatment-experienced patients: AIDS clinical trials group 5211. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:304–312. doi: 10.1086/518797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Jong JJ, et al. Minimal requirements for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 domain to support the syncytium-inducing phenotype: analysis by single amino acid substitution. J. Virol. 1992;66:6777–6780. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6777-6780.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chesebro B, et al. Mapping of independent V3 envelope determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 macrophage tropism and syncytium formation in lymphocytes. J. Virol. 1996;70:9055–9059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9055-9059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pastore C, et al. Intrinsic obstacles to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptor switching. J. Virol. 2004;78:7565–7574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7565-7574.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryser HJ, Fluckiger R. Progress in targeting HIV-1 entry. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munch J, et al. Discovery and optimization of a natural HIV-1 entry inhibitor targeting the gp41 fusion peptide. Cell. 2007;129:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waheed AA, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by amphotericin B methyl ester: selection for resistant variants. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28699–28711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waheed AA, et al. HIV-1 escape from the entry-inhibiting effects of a cholesterol-binding compound via cleavage of gp41 by the viral protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:8467–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701443104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nair V, Chi G. HIV integrase inhibitors as therapeutic agents in AIDS. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007;17:277–295. doi: 10.1002/rmv.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pommier Y, et al. Integrase inhibitors to treat HIV/AIDS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:236–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao G, et al. New developments in diketo-containing inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2007;7:707–725. doi: 10.2174/138955707781024535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savarino A. A historical sketch of the discovery and development of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2006;15:1507–1522. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.12.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dayam R, et al. HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: 2005−2006 update. Med. Res. Rev. 2008;28:118–154. doi: 10.1002/med.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeJesus E, et al. Antiviral activity, pharmacokinetics, and dose response of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor GS-9137 (JTK-303) in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006;43:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233308.82860.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandegraaff N, Engelman A. Molecular mechanisms of HIV integration and therapeutic intervention. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2007;9:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hazuda DJ, et al. Inhibitors of strand transfer that prevent integration and inhibit HIV-1 replication in cells. Science. 2000;287:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldgur Y, et al. Structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic domain complexed with an inhibitor: a platform for antiviral drug design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:13040–13043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pais GC, et al. Structure activity of 3-aryl-1,3-diketo-containing compounds as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:3184–3194. doi: 10.1021/jm020037p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hazuda DJ, et al. A naphthyridine carboxamide provides evidence for discordant resistance between mechanistically identical inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:11233–11238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402357101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sato M, et al. Novel HIV-1 integrase inhibitors derived from quinolone antibiotics. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1506–1508. doi: 10.1021/jm0600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimura K, et al. Broad anti-retroviral activity and resistance profile of a novel human immunodeficiency virus integrase inhibitor, elvitegravir (JTK-303/GS-9137). J. Virol. 2008;82:764–774. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01534-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Markowitz M, et al. Rapid and durable antiretroviral effect of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir as part of combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: results of a 48-week controlled study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007;46:125–133. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318157131c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grinsztejn B, et al. Safety and efficacy of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir (MK-0518) in treatment-experienced patients with multidrug-resistant virus: a phase II randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Markowitz M, et al. Antiretroviral activity, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability of MK-0518, a novel inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase, dosed as monotherapy for 10 days in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006;43:509–515. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802b4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hazuda DJ, et al. Integrase inhibitors and cellular immunity suppress retroviral replication in rhesus macaques. Science. 2004;305:528–532. doi: 10.1126/science.1098632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Espeseth AS, et al. HIV-1 integrase inhibitors that compete with the target DNA substrate define a unique strand transfer conformation for integrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11244–11249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200139397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grobler JA, et al. Diketo acid inhibitor mechanism and HIV-1 integrase: implications for metal binding in the active site of phosphotransferase enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:6661–6666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092056199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marchand C, et al. Metal-dependent inhibition of HIV-1 integrase by beta-diketo acids and resistance of the soluble double-mutant (F185K/C280S). Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:600–609. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fikkert V, et al. Multiple mutations in human immunodeficiency virus-1 integrase confer resistance to the clinical trial drug S-1360. AIDS. 2004;18:2019–2028. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fikkert V, et al. Development of resistance against diketo derivatives of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by progressive accumulation of integrase mutations. J. Virol. 2003;77:11459–11470. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11459-11470.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malet ID, et al. Biochemical cheracterizations of the effect of mutations selected in HIV-1 integrase gene associated with failure to raltegravir (MK-0158).. Conference in Antiviral Therapy; 2007. Barbadospp. S9 (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hazuda DM, et al. Resistance to the HIV-integrase inhibitor raltegravir: analysis of protocol 005, a phase II study in patients with triple-class resistant HIV-1 infection.. Conference in Antiviral Therapy; 2007. Barbadospp. S10 (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cahn P, Sued O. Raltegravir: a new antiretroviral class for salvage therapy. Lancet. 2007;369:1235–1236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McColl DF, et al. Resistance and cross resistance to first generation integrase inhibitors: insights from a phase II study of elvitegravir (GS-9137).. Conference in Antiviral Therapy; 2007. Barbadospp. S11 (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 79.McColl DG, et al. Patterns of resistance to first generation integrase inhibitors: an update on elvitegravir (GS-9137).. Proceedings of the 8th Annual Symposium on Antiviral Drug Resistance; 2007. USA (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Witmer MD, et al. In vitro resistance selection studies using raltegravir: a novel inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase.. Proceedings of the 8th Annual Symposium on Antiretroviral Drug Resistance; 2007. USA (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Freed EO. HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology. 1998;251:1–15. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adamson CS, Freed EO. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly, release, and maturation. Adv. Pharmacol. 2007;55:347–387. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)55010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujioka T, et al. Anti-AIDS agents, 11. Betulinic acid and platanic acid as anti-HIV principles from Syzigium claviflorum, and the anti-HIV activity of structurally related triterpenoids. J. Nat. Prod. 1994;57:243–247. doi: 10.1021/np50104a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li F, et al. PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13555–13560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234683100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou J, et al. The sequence of the CA–SP1 junction accounts for the differential sensitivity of HIV-1 and SIV to the small molecule maturation inhibitor 3-O-{3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl}-betulinic acid. Retrovirology. 2004;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salzwedel K, et al. Maturation inhibitors: a new therapeutic class targets the virus structure. AIDS Rev. 2007;9:162–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kanamoto T, et al. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of YKFH312 (a betulinic acid derivative), a novel compound blocking viral maturation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1225–1230. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1225-1230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou J, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by specific targeting of the final step of virion maturation. J. Virol. 2004;78:922–929. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.922-929.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adamson CS, et al. In vitro resistance to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 maturation inhibitor PA-457 (Bevirimat). J. Virol. 2006;80:10957–10971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou J, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 maturation via drug association with the viral Gag protein in immature HIV-1 particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42149–42155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sakalian M, et al. 3-O-(3′,3′-Dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid inhibits maturation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor assembled in vitro. J. Virol. 2006;80:5716–5722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02743-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to the small molecule maturation inhibitor 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)-betulinic acid is conferred by a variety of single amino acid substitutions at the CA–SP1 cleavage site in Gag. J. Virol. 2006;80:12095–12101. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01626-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smith PF, et al. Phase I and II study of the safety, virologic effect, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of single-dose 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (bevirimat) against human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3574–3581. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00152-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Freed EO, Martin MA. HIVs and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Williams and Wilkins; Lippincott: 2007. pp. 2107–2185. [Google Scholar]