Abstract

This study examines the effects of childhood-onset conduct disorder on later antisocial behavior and street victimization among a group of homeless and runaway adolescents. Four hundred twenty-eight homeless and runaway youth were interviewed directly on the streets and in shelters from four Midwestern states. Key findings include the following. First, compared with those who exhibit adolescent-onset conduct disorder, youth with childhood onset are more likely to engage in a series of antisocial behaviors such as use of sexual and nonsexual survival strategies. Second, youth with childhood-onset conduct disorder are more likely to experience violent victimization; this association, however, is mostly through an intervening process such as engagement in deviant survival strategies.

Keywords: homeless and runaway adolescents, onset of conduct disorder, victimization

Recent studies have shown that homeless and runaway adolescents are a population characterized by a high rate of conduct problems (Buckner & Bassuk, 1997; Cauce, Paradise, & Ginzler, 2000; Feitel, Margetson, Chamas, & Lipman, 1992; McCaskill, Toro, & Wolfe, 1998), delinquent behavior and crime (S. Baron & Hartnagel, 1997; Greenblatt & Robertson, 1993; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999), and physical and sexual victimization (Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Lee & Schreck, 2005; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Researchers also have extensively examined the etiology of their antisocial behavior and victimization and suggested that these activities are influenced by various family, peer, and street factors (S. Baron, 1999; S. Baron & Hartnagel, 1997; S. W. Baron, Kennedy, & Forde, 2001; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Lee & Schreck, 2005; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999; Whitbeck, Hoyt, Yoder, Cauce, & Paradise, 2001).

Most studies have focused on the detrimental effects of socioenvironmental factors such as abusive family background, street adversity, and deviant street social networks (S. Baron, 1999; S. Baron & Hartnagel, 1998; S. W. Baron, Kennedy, & Forde, 2001; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Lee & Schreck, 2005; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). For example, Hagan and McCarthy (1997) found that situational adversities such as lack of food, shelter, and money while on the street have positive effects on delinquency and criminal behavior. However, to understand the origin of homelessness and street experiences, it is also necessary for researchers to examine stable individual propensities and their long-term cumulative effects. As suggested by Baum and Burnes (1993), homelessness and crime share causes that are related to not only the structural circumstances and social experiences they encounter but also the characteristics of the people involved. Unfortunately, most homeless studies fail to take individual differences such as childhood conduct problems into account and may overestimate effects of other structural and situational risk factors. As Hagan and McCarthy observed, social–environmental factors and individual propensity “are seldom considered simultaneously in crime research” (p. 133).

The relative paucity of research is puzzling given what is known about the link between childhood conduct problems and delinquent behavior, serious crime, and other negative social consequences among youth offenders. Evidence from longitudinal studies consistently has found that early onset of conduct problems is a significant factor that discriminates between adolescents with serious antisocial behavior and those with little or less serious antisocial behavior. Childhood onset of antisocial behavior predicts more frequent, serious, and persistent antisocial behavior than adolescent onset (Hinshaw, Lahey, & Hart, 1993; Lahey, Loeber, & Quay, 1998; Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b, 1997; Moffitt & Lynam, 1992; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997; Quay, 1993). Given these connections, it may be logical to expect that homeless adolescents with childhood-onset conduct disorder (CD) would be at more increased risk of delinquent behavior and other negative consequences than other homeless adolescents while they are on the street.

The neglect of individual differences in previous homeless studies may lead to other problems. For example, the estimation of associations between socioenvironmental factors and delinquency and street crime found in previous studies (S. Baron, 1999; S. Baron & Hartnagel, 1997; S. W. Baron et al., 2001; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999) may be biased. The causal associations between street situational risk factors and crime could be spurious or significantly inflated. For instance, a coercive interactional style developed during childhood may lead to identification with a delinquent subculture or more difficulties in street adjustment, which increases delinquency and street crime among homeless adolescents (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). In other words, individual differences such as childhood conduct problems may account for both delinquency and higher exposure to street-specific situational risk factors such as identification with the street subculture. As a result, without controlling for individual propensity, any observed positive correlation between street risk factors and delinquency and crime may be biased.

The study presented here addresses this problem by simultaneously examining the effects of individual propensity, family background, peers, and street situational factors on delinquent behavior and violent victimization. Specifically, this study assesses the long-term effects of childhood onset of CD on street experiences among a group of homeless and runaway adolescents. First, based on the age of onset of CD, our study examines the heterogeneity of antisocial behaviors such as (a) association with deviant peers and engagement in delinquent survival strategies and (b) victimization. We compare the prevalence of antisocial behavior and victimization between two homeless and runaway subgroups: adolescents with childhood-onset CD and those with adolescent-onset CD. Second, using structural equation modeling, we explore the mechanism that links onset of CD and other negative social consequences. Specifically, we extend the literature on victimization by incorporating onset of CD and assessing its direct effects and indirect effects on victimization through association with deviant peers and involvement with delinquent behavior.

Theoretical Background

Onset of CD and Delinquent Behavior

Longitudinal studies have consistently found that conduct problems during childhood are significant predictors of antisocial behavior and psychopathology during adolescence and adulthood (Hinshaw et al., 1993; Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b: Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997). Compared with the majority of youth who offend during adolescence, youth with childhood conduct problems are more likely to engage in delinquent behavior and crime in different periods and settings as well as have other negative characteristics such as inadequate parenting, neurocognitive problems, and weak attachment to school and family (Loeber, 1982; Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Moffitt et al., 1996). An exhaustive review by Farrington and colleagues (1990) suggests that early onset of antisocial behavior is the best predictor of persistent and serious crime during adolescence and adulthood. Indeed, although most children with conduct problems do not become antisocial adults, most antisocial adults do have a history of childhood conduct problems (Loeber, 1982; Olweus, 1979). The stability of antisocial behavior is strongly associated with the age of onset of conduct problems.

The robust relationship between age of onset of conduct problems and chronic offending has led some to theorize that there are two distinct developmental trajectories to CD (Hinshaw et al., 1993; Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997). For example, Moffitt (1993a, 1993b) suggested that there are at least two types of offenders—childhood-onset offenders and adolescent-onset offenders—each with a unique set of factors related to criminal and antisocial activity as well as a different pattern of antisocial behavior over the life-course. Patterson and colleague (Patterson, 1982, 1995; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997) proposed a similar two-trajectory model that differentiates early starters versus later starters. Although these two theories differ in certain aspects, both predict that individuals with childhood onset/early starters are more frequently involved with delinquent behavior and are more likely to engage in persistent offending than adolescent onsets/later starters (Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997). This line of research has been so influential that the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMIV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) has adopted this approach as part of its nomenclature for distinguishing subtypes of CD (i.e., Childhood-Onset Type, Adolescent-Onset Type).

Onset of CD and Deviant Survival Strategies Among Homeless and Runaway Adolescents

One type of delinquency and crime that homeless and runaway adolescents engage in daily is the use of deviant survival strategies while on the street (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Because of their marginal economic status, a large proportion have engaged in delinquent behavior and crime to meet their basic needs (S. Baron & Hartnagel, 1997; Greenblatt & Robertson, 1993; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Homeless adolescents report use of sexual survival strategies such as trading sex for money, shelter, or drugs, as well as nonsexual strategies such as breaking into a house, drug dealing, stealing and shoplifting, and scavenging food from dumpsters (Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Although past research has not linked childhood conduct problems to the use of deviant survival strategies, we have reason to believe that homeless and runaway youth with childhood conduct problems are more likely to engage in these activities. First, most survival strategies employed by these adolescents, including selling drugs for money, shoplifting, breaking into a store or house, and trading sex, are against the law. As previously discussed, individuals with childhood onset are more likely to commit delinquent behavior and crime, thus they are more likely to engage in deviant survival strategies when they are on the street. Second, adolescents with childhood CD may be more likely to have poor relationships with family and other conventional institutions than those with adolescent onset (Hinshaw et al., 1993; Moffitt, 1993a; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997) and have to resort to illegal activities to meet their daily necessities. Although most homeless youth have weak social bonds with their families and other conventional institutions such as social service agencies, some do have relatively stronger connections with their family members, friends from families, or social workers (Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2005). However, because youth with childhood CD are disproportionately raised by disadvantaged families characterized by low socioeconomic status, single parents, and ineffective parenting practices (Moffitt, 1993a; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997), they are more likely to be the ones who have weaker social bonds. The lack of emotional and material support from families and other social agencies may lead to more frequent involvement with illegal activities. Third, compared with individuals with adolescent onset, those with childhood onset are more likely to have limited social skills such as poor academic achievement and low self-esteem (Patterson & Yoerger, 1997), which may prevent them from obtaining or keeping legitimate employment.

Although much research has found an association between childhood conduct problems and delinquency and crime in the general population, the empirical studies reviewed have not examined this association among the homeless. However, limited evidence does suggest that stable individual propensities contribute to the high rates of delinquency and crime in this population. Early studies, mainly research from the 1940s to 1970s, have suggested that homeless adolescents are heterogeneous in nature and have linked street deviance and crime to individual propensity such as pathological personalities (see Armstrong, 1932, 1937; Robins & O'Neal, 1959). This approach, however, is not fully integrated into current homeless youth research. We located only two studies that examined effects of individual propensity on street delinquent behavior and crime. S. Baron (2003) found some evidence that homeless youth with low self-control reported an elevated level of involvement with a series of criminal behaviors and drug use. Those with low self-control were also more likely to have other negative social characteristics such as having deviant peers and deviant values, to be unemployed for longer periods of time, and to be homeless for greater periods of time. Hagan and McCarthy (1997) also found that individual differences had effects on street crime, especially violent street crime; however, their study did not have a direct measure of individual propensity and used prior delinquent behavior and youth-initiated violence against parents as indicators reflecting time-stable individual propensity.

Onset of CD and Violent Victimization

Although longitudinal studies have established the association between age of onset of CD and delinquency and crime in the general population, few studies have examined the linkage between CD and violent victimization. From limited literature, however, we believe onset of CD may directly and indirectly contribute to the experience of violent victimization. Childhood-onset CD may increase the chance of violent victimization directly. First, individuals with childhood conduct problems are more likely to come from disadvantaged families or neighborhoods (Frick, 1994; Moffitt, 1993a; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), thus they are more likely to be exposed to violent victimization during their childhood, which may increase their chances of revictimization during adolescence and adulthood (Wittebrood & Nieuwbeerta, 2000). Second, individuals with childhood CD are more likely to have neurocognitive deficiencies such as low IQ, lack of verbal skills, problems of impulsivity and motor hyperactivity (Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b), and insensitivity to others (Moffitt, 1993a; Moffitt et al., 1996; Moffitt & Lynam, 1992), which may leave them more vulnerable to violent victimization. Third, individuals with childhood CD are more likely to be victimized because of their coercive interactional style developed during early childhood (Moffitt, 1993a; Moffitt et al., 1996; Patterson, 1982, 1995; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997). As suggested by Patterson (1982, 1995), children with difficult temperament, when coupled with ineffective and inconsistent parenting, are likely to develop a coercive interactional style, which may extend to other situations such as schools and peers when these children grow up. The coercive interactional style may, at least, provoke others and lead to physical confrontations, which increases their chances of violent victimization.

Childhood CD may also indirectly increase experiences of violent victimization through association with deviant peers and offending behavior. First, individuals with childhood CD are more likely to associate with deviant peers during their childhood and adolescence (Patterson, 1982, 1995), which increases their chances of physical confrontations and violent victimization (Hindelang, Gottfredson, & Garofalo, 1978; Schreck, 1999; Schreck & Fisher, 2004; Schreck, Wright, & Miller, 2002). As suggested by Hindelang et al. (1978), persons who “share sociodemographic characteristics with potential offenders are more likely to interact socially with such potential offenders, thus increasing the risk factor of exposure” (pp. 257−259). Because most adolescents with childhood CD are rejected by conventional peers from childhood and have minimal social skills compared with others (Patterson & Yoerger, 1997), they may largely depend on deviant peers for emotional support. The frequent contact with deviant peers increases individuals’ chance of being victimized by peers in the group and outside of the group. Second, as indicated by previous studies, the associations between individual and situational risk factors and violent victimization are mediated by individuals’ own offending behavior (Jensen & Brownfield, 1986; Lauritsen, Sampson, & Laub, 1991; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1990). Research on victimization has shown a linkage between a deviant lifestyle and victimization (Jensen & Brownfield, 1986; Hindelang et al., 1978). For example, Sampson and his colleagues found that there was a large overlap between delinquent behavior/crime and victimization (Lauritsen et al., 1991; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1990), suggesting that involvement with delinquency and crime put individuals at a higher risk of victimization. Similar results were replicated among a group of homeless youth. Adolescents who were more involved with deviant survival strategies were more likely to be physically or sexually victimized (Whitbeck et al., 2001). Because adolescents with childhood-onset CD are more likely to associate with deviant peers and engage in delinquent behavior and crime more persistently than those with adolescent-onset CD, we expect age of onset of CD contribute to the experiences of violent victimization indirectly.

Although the association between onset of CD and violent victimization is theoretically sound, no studies were found that empirically tested this linkage. Previous research, however, does show that stable individual propensity is associated with violent victimization (Schreck, 1999; Schreck & Fisher, 2004; Stewart, Elifson, & Sterk, 2004). Self-control, for example, is linked to violent victimization because individuals with low self-control share certain personality patterns such as having a low tolerance for frustration, lacking tenacity and persistence, preferring physical rather than mental activities, and being more inclined to involve themselves in thrill-seeking activities (Schreck, 1999). The effect of self-control on violent victimization may be mediated through other mechanisms such as social bonding with families and association with deviant peers; however, even when family, peer, and other situational risk factors are controlled, personal traits such as self-control still contribute to the experience of violent victimization (Schreck & Fisher, 2004). Similar results are replicated among a group of female offenders (Stewart et al., 2004).

Hypothesized Model

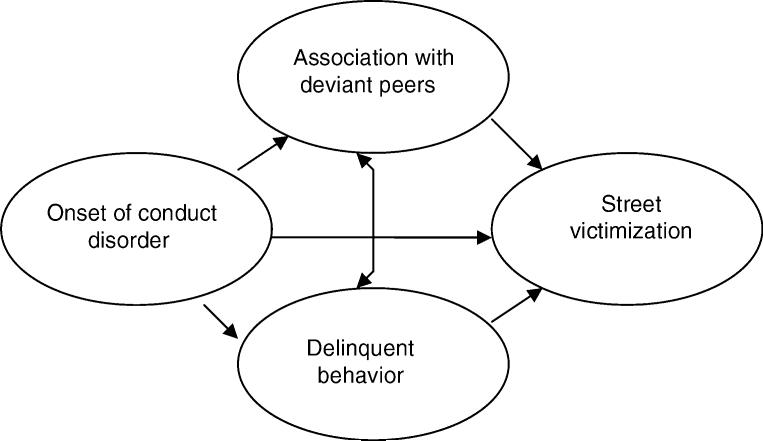

Based on the previous literature, Figure 1 presents a theoretical model that links onset of CD, street survival strategies, and violent victimization among runaway and homeless adolescents. Specifically, four hypotheses linking onset of CD and deviant subsistence strategies and street victimization are examined.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model

Hypothesis 1

Compared to those with adolescent-onset CD, homeless and runaway adolescents with a childhood-onset CD are more likely to resort to delinquent survival strategies, including sexual and nonsexual strategies.

Hypothesis 2

Homeless and runaway adolescents with childhood-onset CD have a higher level of association with deviant peers compared to those with adolescent-onset.

Hypothesis 3

Childhood-onset CD may directly increase experience of violent victimization, including physical and sexual victimization.

Hypothesis 4

Childhood-onset CD may indirectly increase violent victimization through association with deviant peers and involvement in deviant subsistence strategies while on the street.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The data were collected in the spring of 2000. There were 428 (187 male, 241 female) homeless youth interviewed directly on the streets and in shelters in eight midwestern cities (St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, Lincoln, Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, Iowa City, Wichita) by full-time specially trained street interviewers. To obtain a representative sample of homeless and runaway adolescents, we designed a sampling strategy that incorporated sampling units of fixed and natural sites similar to the design used by Kipke in her Los Angeles study of homeless youth (Kipke, Simon, Montgomery, Unger, & Iverson, 1997), with a yearlong window of sampling to capture the time dimensions. The sampling design involved repeatedly checking locations where homeless youth were likely to be found in each of the target cities. Locations included shelters and outreach programs serving homeless youth, drop-in centers, and various “street” locations where young homeless people were most likely to be located. Research has demonstrated that using sampling designs that involve multiple points of entry to homeless populations is most effective in generating a diverse sample (Burt, 1996; Koegel, Burnam, & Morton, 1996). The interviewers all had prior experience in their respective cities as youth outreach workers and brought considerable knowledge regarding optimal areas of the city for locating youth on their own. The sampling protocol included going to these locations in the cities at varying times of the day on both weekday and weekends over the course of 12 months. Because episodes of homelessness are of varying duration, a 1-year time frame provided an increased probability of capturing youth who have short-term exposure to homelessness. The interviewers were instructed to continue recruiting until their caseload reached 60 adolescents whom they would then track and reinterview at 3-month intervals.

Street interviewers underwent 2 weeks of intensive training regarding computer-assisted personal interviewing procedures and administering the four indices (major depressive episodes, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use/abuse, and drug use/abuse) from the University of Michigan–Composite International Diagnostic Interview and one index (CD) from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised (DISC-R). They then returned to their shelters and administered several “practice” interviews with staff and respondents 20 years old or older. After completing their practice interviews, the interviewers returned to the university for a 2nd week of training. All interviews were conducted on laptop computers and electronically downloaded to a secure university server.

All participants were between the ages of 16 and 19 and met the study's criteria for homelessness. Homelessness was defined as residing in a shelter, living on the street, or living independently (e.g., friends, transitional living) because they had run away, been pushed out, or drifted out of their families of origin. Sixty-one percent of male participants interviewed and 39% of female participants had spent at least one night directly on the streets. When asked where they stayed “last night” (i.e., night prior to interview), 40% had spent the night in a shelter, 11% in a relative's home, 16% in the home of a friend or “acquaintance,” 16% in a foster/group home (operated by the street agency), 6% in their own apartment (transitional living programs operated by street agency), and a little more than 10% had been in an abandoned house, on the street, or in similar settings. The number of times adolescents had runaway ranged from 1 to 51 times with a mean of 8 runs (SD = 11.2).

The adolescents were an average age of 17.4 years (SD = 1.05). Fifty-nine percent were European American, 22% were non-Hispanic African American, and 5% were Hispanic. The remaining participants (14%) identified themselves as American Indian, Asian or Pacific Islander, or biracial. Fifteen percent identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Sixty-two percent reported that they were born in a city with a population of 100,000 or more, 10% said they were from a suburb of a large city, 8% a medium-sized city of 50,000 to 100,000, 8% a small city of 10,000 to 50,000, and 12% from small towns or rural communities of 10,000 or fewer.

Adolescents were informed that this was a longitudinal study. Informed consent was a two-stage process. First, the study was explained, and informed consent was obtained from the adolescent. They were assured that refusal to participate in the study, to answer specific questions, or to discontinue the interview process would have no effect on current or future services provided by the outreach agency in which the interviewer was placed. Second, all adolescents were asked if their parents could be contacted. If permission was granted, parents were contacted, and informed consent was obtained. If the adolescent was sheltered, we followed shelter policies of parental permission for placement and guidelines concerning granting such permissions. These policies were always based on state laws. In the few cases where the adolescents were younger than 18, were not sheltered, and refused permission to contact parents, the adolescents were treated as emancipated minors in accord with National Institute of Health guidelines (Title 45, Part 46, Code of Federal Regulations, DHHS 2001). A National Institute of Mental Health Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained to protect the respondent's statement regarding potentially illegal activities (e.g., drug use).

The first-wave interview consisted of two parts. The first component was a social history and symptom scales. The respondent was then asked to meet for a second interview during which the diagnostic interview was conducted. Based on interviewer reports, approximately 90% of the adolescents who were approached for an initial interview and who met study criteria agreed to participate in the study. Of 455 respondents who completed the first interview, 94.3% (n = 428) completed the second baseline interview. The respondents were paid $25 for the first interview and $25 for the second.

Measures

Onset of CD

To assess behavioral problems, the conduct disorder module was used from the DISC-R. The DISC-R is a highly regarded, structured interview intended for use with trained interviewers who are not clinicians. It has been shown to have from good to excellent interrater and test–retest reliability (Jenson et al., 1995; Schaffer et al., 1993) and is considered a state-of-the-science structured interview for use in assessing behavioral disorders of childhood and adolescence (Schaffer et al., 1993; Schwab-Stone et al., 1993; Weinstein, Noam, Grimes, Stone, & Schwab-Stone, 1990). For detailed information about specific diagnostic criteria, please see the first appendix table. Onset of conduct disorder is a dichotomized variable with 1 (childhood onset) and 0 (adolescent onset). Adolescents who met the criteria of CD and met at least one criterion characteristic of CD prior to age 10 were defined as having childhood onset (American Psychiatric Association, 2003).

Family abusive background

Researchers have found that family background, especially abusive family background such as physical and sexual abuse at home, is an important determinant of leaving home and engaging in various delinquent activities (S. W. Baron et al., 2001; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Lee & Schreck, 2005; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). In addition, physical and sexual abuse during childhood are strong predictors of adolescent or adult revictimization (Wittebrood & Nieuwbeerta, 2000). Caretaker physical abuse was measured with an eight-item scale that asked adolescents how often a parent or adult caretaker who was supposed to be taking care of them ever punished them by making them go a full day without food or water, abandoned them for at least 24 hours, threw something at them in anger, pushed them, slapped them, hit them with an object, beat them up with their fist, and threatened or assaulted them with a weapon (Straus & Gelles, 1990). A mean procedure was performed to create a composite measure. Scale scores were coded such that the higher the score, the higher the abuse. Cronbach's alpha for caretaker physical abuse was .82.

Caretaker sexual abuse was measured by a two-item scale that asked adolescents how often a parent or adult caretaker who was supposed to be taking care of them ever asked them to do something sexual or forced them to do something sexual. Because of the skewness of this measure, this composite measure was dichotomized so that 0 indicates never and 1 indicates at least one time. The correlation between these two items was .86. One fourth of these adolescents reported that they have been asked or forced to have sex by adult caretakers at least once.

Street exposure

Recent studies have suggested that more proximate factors such as marginal street economy, especially lack of housing, money, food, and jobs, are the main factors that contribute to delinquency and crime among homeless adolescents (Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Lee & Schreck, 2005). Street experiences such as time spent on the street, especially spending nights directly on the streets, coupled with adolescents’ embeddedness in street social networks that promote deviance and crime (S. W. Baron et al., 2001; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997, McCarthy, Hagan, & Martin, 2002; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999), leads to an elevated level of delinquency and criminal behavior among homeless adolescents. Street exposure is also related to street victimization. For example, studies found that adolescents living on the street for one night or more were more likely to experience physical and sexual victimization (Tyler, Hoyt, & Whitbeck, 2000; Tyler, Hoyt, Whitbeck, & Cauce, 2001; Whitbeck et al., 2001). In addition, many of these youth run away from home at an early age (Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999), which makes them ideal targets for victimization because of their inability to physically protect themselves.

We measured street exposure by using two items: ever spent one or more nights on the street and age on own. Adolescents were asked if they had ever spent one or more nights on the street in an abandoned building or another place out in the open. Those individuals who had not spent at least one night on the street were coded as 0. Approximately 49% of the sample had spent at least one night on the street. Age on own was a single item. Adolescents reported how old they were when they left home and were on their own for the first time. The mean age adolescents were first on their own was 13.4 years old (SD = 2.97).

Association with deviant peers was measured using a 12-item scale that asked adolescents if any of their friends had engaged in deviant behaviors, included running away, selling drugs, using drugs, being suspended from school, dropping out of school, shoplifting, breaking and entering, stealing, selling sex, being arrested, and threatening or assaulting someone with a weapon (Whitbeck & Simons, 1990). The response categories for each item were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). A mean procedure was then performed to create a composite scale of association with deviant peers, with high scores indicating an increased association with deviant peers. Because the scale was created from dichotomous questions, the KR20 was used to assess internal consistency (Kuder & Richardson, 1937). The KR20 coefficient was .87.

Deviant subsistence strategies and violent victimization

We examined both sexual and nonsexual deviant subsistence strategies employed by homeless and runaway adolescents. Sexual deviant subsistence strategies was measured using three items in which the respondents were asked if they had ever traded sex for food or shelter, traded sex for money, or traded sex for drugs since they were on their own (adapted from Whitbeck & Simons, 1990). The three items were summed and then dichotomized. Those who had never traded sex were coded as 0 and those who had traded sex were coded as 1. Participation in nonsexual deviant subsistence strategies was assessed by six items that focused on different tactics that adolescents may have used to survive on the street (adapted from Whitbeck & Simons, 1990). Adolescents were asked to report if they had ever spare changed for money or for food, broken in and taken things from a store or house for money, sold drugs for money, stole or shoplifted food, or engaged in dumpster diving for food. The summated scale had a KR20 coefficient of .65 and ranged from 0 to 6, with higher values indicating engaging in more deviant subsistence strategies.

Similarly, to measure violent victimization, we examined physical and sexual victimization experienced by these adolescents while on the street. Physical victimization when adolescents were on their own was assessed with a four-item scale in which the adolescents were asked to report how often they had been beaten up, robbed, threatened with a weapon, and assaulted with a weapon. Response categories were never, once, two to five times, and more than five times. The mean scale has an alpha reliability of .71 and ranges from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more frequent victimization. Our measure of sexual victimization consisted of two items that focused on whether respondents had any unwanted or unpleasant sexual experiences with people since they had been on their own. Adolescents were asked, “How often have you been asked to do something sexual that you didn’t want to” and “How often have you been sexually assaulted or raped?” Respondents who answered yes to either of the items were coded 1 (being sexually victimized). More than one third (37.1%) of the respondents reported that they had been sexually victimized when on the streets.

Covariate variables

Our analysis controlled demographic variables age and gender. Age of adolescent at time of interview was calculated using the date of birth of the respondent and the date of the baseline interview. Age ranged from 16 to 19 with a mean age of 17.4 (SD = 1.05). Gender of adolescent was coded 0 for female and 1 for male (54% vs. 46%, respectively). Each of these variables is a correlate of delinquent behavior and victimization and is sometimes interpreted as a proxy of lifestyles with high victimization risk (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Cohen, Kleugel, & Land, 1981; Finkelhor & Asdigian, 1996; Hindelang et al., 1978; Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, Tyler, & Johnson, 2004). The second appendix table presents detailed information of bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations of all study variables.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Among the 428 homeless and runaway adolescents, three fourths (75.7%, n = 324) were classified as having lifetime CD. Of these, 63% (n = 203) were classified as having childhood onset of CD. Because our study focuses on the effect of age of onset of CD on deviant street behavior and victimization, youth who did not meet lifetime CD characteristic criteria were excluded (n = 104). In addition, of the 203 adolescents with childhood-onset CD, 28 had onset after their first runaway. To avoid confounding effects between onset of CD and street situational factors, these 28 cases were also excluded from this study. Six cases were also excluded from this study because of a listwise deletion. Overall, of the 428 homeless youth, 290 (68%) were retained for the analysis.

We first compared the distribution of association with deviant peers, use of subsistence strategies, and street victimization between adolescents with childhood-onset CD and those with adolescent-onset CD. Using t test of means comparisons, our findings reveal that adolescents with childhood onset reported a higher level of use of survival strategies than those with adolescent onset (see Table 1). For example, although a large percentage of street youth reported use of deviant subsistence strategies, adolescents with childhood onset reported more frequent delinquent behavior and serious crime such as taking something from someone, selling drugs, and stealing or shoplifting from stores. In addition, adolescents with childhood-onset CD were more likely to engage in deviant sexual strategies, especially trading sex for money and drugs. However, there was no significant difference between these two groups in terms of less serious delinquent behavior such as panhandling/spare changing. It is also interesting to learn that adolescents with childhood-onset CD were more likely to engage in dumpster diving for food. As expected, we also found that adolescents with childhood-onset CD reported more frequent association with deviant friends.

Table 1.

Comparison of Association With Deviant Peers, Use of Subsistence Strategies, and Street Victimization Between Youth With Childhood-Onset Conduct Disorder Versus Adolescent-Onset Conduct Disorder (t Test)

| Conduct Disorder | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | Childhood Onset (%) | Adolescent Onset (%) | |

| Association with deviant peers | 0.70 | 0.73* | 0.66 |

| Nonsexual strategies | |||

| Panhandling or spare changing | 17.97 | 20.23 | 14.75 |

| Take something from a store | 27.03 | 33.53** | 17.89 |

| Sold drugs | 50.34 | 58.38** | 39.02 |

| Stealing or shoplifting | 18.92 | 23.12** | 13.01 |

| Dumpster diving | 5.07 | 7.51** | 1.63 |

| Sexual strategies | |||

| Trade sex for food/shelter | 7.43 | 8.68 | 5.69 |

| Trade sex for money | 8.11 | 11.56** | 3.25 |

| Trade sex for drugs | 6.42 | 9.25** | 2.44 |

| Physical victimization | |||

| Ever been beaten up | 37.50 | 39.31 | 34.96 |

| Ever been robbed | 32.09 | 38.15** | 23.58 |

| Been threatened with a weapon | 52.03 | 56.65† | 45.53 |

| Been assaulted and wounded with a weapon | 25.34 | 30.64* | 17.89 |

| Sexual victimization | |||

| Unwanted sex | 36.95 | 36.63 | 37.40 |

| Been sexually assaulted or raped | 19.56 | 16.76 | 22.76 |

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.10.

Our findings also indicated that adolescents with childhood onset reported more extensive victimization experiences than those with adolescent onset (see Table 1). The magnitude of these differences (as measured with t tests), however, varies substantially by the form of victimization. For example, adolescents with early onset reported an elevated rate of violent victimization such as being robbed (38% vs. 24%), being threatened with a weapon (57% vs. 46%), and being assaulted and wounded with a weapon (31% vs. 18%). However, no significant differences in sexual victimization were found.

Structural Equation Modeling

Structural equation modeling (Mplus 3.0) allows us to evaluate our theoretical model by simultaneously identifying the direct and indirect effects of onset of CD on delinquency and victimization while taking other risk factors into account. Because observed indicators of deviant nonsexual and sexual strategies were dichotomized, unweighted least square method was used to estimate the final model (Muthén & Muthén, 2001). A fully recursive model that links onset of CD, deviant survival strategies, and violent victimization was tested (Table 2). Because this model was saturated, no model fit indexes such as chi-square or other goodness-of-fit indexes are presented.

Table 2.

Fully Recursive Structural Equation Model Linking Onset of Conduct Disorder, Deviant Survival Strategies, and Violent Victimization

| Deviant Peers | Nonsexual Survival Strategies | Sexual Survival Strategies | Physical Victimization | Sexual Victimization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | B | β | B | β | B | β | |

| Childhood onset of conduct disorder | 0.05 | .09 | 0.48** | .17 | 0.47* | .20 | 0.03 | .02 | −0.21 | −.08 |

| Age | 0.01 | .05 | 0.01 | .01 | 0.26** | .25 | 0.13* | .20 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Gendera | 0.00 | .00 | 0.43** | .15 | −0.42* | −.18 | 0.06 | .04 | −0.90** | −.37 |

| Physical abuse | 0.03 | .08 | 0.05 | .02 | −0.06 | −.04 | 0.14** | .15 | 0.21* | .13 |

| Sexual abuse | 0.08** | .15 | 0.07 | .02 | 0.23 | .09 | 0.17** | .11 | 0.63** | .22 |

| Age on own | −0.01 | −.10 | 0.00 | .01 | −0.03 | −.05 | −0.03** | −.11 | −0.05 | −.09 |

| Ever on the street | 0.06* | .11 | 1.06** | .38 | 0.59** | .26 | 0.16* | .11 | −0.10 | −.04 |

| Deviant peers | 0.34* | .12 | 0.36 | .07 | ||||||

| Nonsexual survival strategies | 0.11** | .22 | 0.12 | .13 | ||||||

| Sexual survival strategies | 0.08 | .12 | 0.26* | .24 | ||||||

| R2 or pseudo R2 | 9% | 24% | 23% | 38% | 42% | |||||

Note: N = 290

1 = male

p < .05.

p < .01 (one-tailed test)

Direct and Indirect Effects of Childhood Onset of CD

Consistent with bivariate analysis, childhood onset of CD predicted an elevated level of delinquent behavior such as sexual and nonsexual deviant strategies while on the street. Specifically, those with childhood onset were more likely to trade sex for money, food and shelter, or drugs (β = .20); in addition, these adolescents were more likely to use deviant survival strategies such as breaking into a store or a house, stealing/shoplifting, and selling drugs to meet their daily needs (β = .17). Our first hypothesis is supported. However, after covariates such as family and street risk factors were taken into account, the significant association between onset of CD and association with deviant peers disappeared. Our second hypothesis, which states that adolescents with childhood onset of CD have higher levels of association with deviant peers, is thus rejected.

Our third hypothesis, which states that childhood onset of CD increases violent victimization while on the street directly, is also rejected. No significant direct association was found between onset of CD and physical and sexual victimization. However, the model indicated that age of onset of CD had indirect effects on victimization through engagement in deviant subsistence strategies. Specifically, involvement with sexual subsistence strategies strongly predicted sexual victimization (β = .24), and use of nonsexual strategies strongly predicted physical victimization (β = .22). A formal analysis of indirect effects provided further support, suggesting that age of onset of CD had significant indirect effect on violent victimization while on the street (result not shown). Specifically, through mostly use of nonsexual deviant strategies, age of onset of CD had a significant indirect effect on physical victimization (β = .07, t = 2.62); similarly, age of onset of CD had a significant indirect effect on sexual victimization (β = .08, t = 1.96). Our final hypothesis is thus supported.

Effects of Abusive Family Background

Abusive family background appears to have significant effects on association with deviant peers and violent victimization experiences. Specifically, physical abuse by caretakers at home significantly increased the chance of being physically victimized (β = .15) and sexually victimized while on the street (β = .13). Similarly, sexual abuse by caretakers predicted an elevated level of physical victimization (β = .11) and sexual victimization (β = .22). Being sexually abused at home also increased adolescents’ involvement with deviant peers (β = .15).

Effects of Street Exposure

As expected, street exposure was significantly associated with deviant survival strategies. Staying on the street or other public places for one night or more increased the risk of associating with deviant peers (β = .11), and engaging in sexual (β = .26) and nonsexual deviant subsistence strategies (β = .38). Street exposure was also associated with experiences of violent victimization. Specifically, early independence on the street predicted an elevated level of physical victimization (β = −.11). That is, adolescents who were first on the street at an early age were more likely to be physically victimized, possibly because of their physical vulnerability. In addition, staying on the street for one night or more predicted a higher level of physical victimization (β = .11). Finally, association with deviant peers increased the level of physical victimization while on the street (β = .12).

Effects of Covariate Variables

Effects of age and gender were examined in this model (Table 2). Age was positively associated with participation in deviant sexual strategies (β = .25) and directly associated with physical victimization (β = .20). Gender was significantly associated with participation in sexual and nonsexual strategies. Female adolescents were more likely to participate in sexual subsistence strategies (β = −.18), and male adolescents were more likely to participate in nonsexual strategies (β = .15). In addition, there was a strong direct association between gender and sexual victimization (β = −.37), indicating that girls were much more likely to be sexually victimized even when their deviant sexual activities and other factors were taken into account.

Discussion and Conclusions

Much attention has been paid to the high prevalence of disruptive behavior, crime, and street victimization, as well as structural and situational risk factors that lead to antisocial behavior among homeless and runaway adolescents. Most of these studies, however, fail to take into account stable individual propensities such as childhood conduct problems. Using a sample of 290 CD homeless youth, this study simultaneously examines effects of individual propensity, abusive family background, peers, and street situational factors on street experiences. In addition, this study explores the mechanism that links onset of CD, delinquent survival strategies, and street victimization.

Our research provides support for the argument that stable individual propensity, along with family, peers, and street situational risk factors, should be taken into account in explaining delinquent behavior and crime (Baron, 2003; Hagan & McCarthy, 1997). Consistent with previous literature (Hinshaw et al., 1993; Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Moffitt et al., 1996; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997), adolescents with childhood conduct problems exhibit an elevated level of delinquent behavior. Although most homeless adolescents use deviant survival strategies such as spare changing, youth with childhood onset are more likely to break into a store, to steal, and to sell drugs. These youth are also more likely to use sex as a strategy to get money or drugs. The higher level of delinquency and crime among adolescents with childhood-onset CD may be because of two reasons. First, as Moffitt and Patterson's two-trajectory model suggests, youth with childhood onset are more impulsive, short-sighted, and aggressive (Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Patterson, 1982). Their social and personal vulnerability may be further amplified when they are on the street (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). When facing daily stress such as hunger, housing problems, and violence, adolescents with childhood conduct problems may be more likely to respond with further delinquent behavior and serious crime. This pattern of behavior could be reinforced in the street subculture because aggression and crime is expected and is routinely taken as an effective coping strategy by street peers (Baron et al., 2001). Second, adolescents with childhood-onset CD may have little social support from friends or families to buffer the negative effects of stressful street life. Previous research has shown that most homeless youth have weak social bonds with families and other conventional institutions (Johnson et al., 2005; Unger et al., 1998); adolescents with childhood CD, however, may have even less family and peer resources because of their disadvantaged family background and their coercive interactional style (Moffitt, 1993a, 1993b; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997). Their vulnerability is further exacerbated because of their lack of social skills such as poor education achievement and a lack of self-esteem (Baron, 2003; Patterson & Yoerger, 1997), which may prevent them from obtaining and keeping legal income sources such as stable employment.

Unexpectedly, there is no association between onset of CD and association with deviant peers. Although bivariate analysis showed significant differences of peer delinquency between adolescents with childhood onset and those with adolescent onset, the difference decreased to nonsignificance when abusive family background and street exposure indicators were taken into account. This may imply that part of the common variance shared by onset of CD and peer delinquency is because childhood-onset CD adolescents are disproportionately raised by disadvantaged or abusive families (Frick, 1994; Moffitt, 1993a; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), or adolescents with childhood onset are more likely to stay on the street for longer time, which leads to a higher level of association with deviant peers.

This study also extends previous research on victimization by incorporating age of onset of CD and examining the direct and indirect effects of onset of CD on violent victimization. Although it is known that homeless adolescents have a higher rate of victimization than the general population (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999), this study shows that there is much heterogeneity of violent victimization even in this high-in-risk population. Compared with those with adolescent onset, youth with childhood onset have even higher rates of violent victimization. The association, however, is mainly because of their elevated level of delinquent behavior and crime. As Sampson and Lauritsen (1990) and other routine activity theorists have suggested, delinquent activities lead to an elevated level of exposure to conflictual situations, which in turn leads to physical or sexual victimization. It appears that adolescents with childhood-onset CD are more likely to engage in a series of antisocial behavior while on the street, which increases their risk of being physically and sexually victimized. Although there is little research that links childhood conduct problems to later victimization, our study provides further support for the argument that stable individual propensity is associated with violent victimization (Schreck, 1999; Schreck & Fisher, 2004; Stewart et al., 2004). For example, Schreck and colleague (Schreck, 1999; Schreck & Fisher, 2004) argued that low self-control is associated with a higher risk of violent victimization.

Finally, this study provides support for the previous research that claims abusive family background and street exposure contributes to an elevated level of victimization (Hagan & McCarthy, 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). For example, the more prominent risk factors for sexual victimization are sexual abuse at home, use of sexual survival strategies while on the street, and being female. The experience of sexual victimization by family members may alter an individual's perception of self-efficacy or change one's perceptions of and beliefs about others in society (Macmillan, 2001), which may directly or indirectly increase later sexual victimization (Macmillan, 2001; Wittebrood & Nieuwbeerta, 2000). Being female has direct effects on sexual victimization even after abusive background and survival strategies were taken into account. As suggested by Finkelhor and Asdigian (1996), girls and women are more likely to be sexually victimized simply because of their gender. Similarly, being physically victimized while on the street is associated with a series of family, peers, and street situational factors (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Experiences of physical or sexual abuse at home, early independence on the street, spending nights on the street, associating with deviant peers, and delinquent behavior all contribute to a higher level of physical victimization.

It should be noted that there are some limitations to this study. First, the study uses self-reports for age of onset. Although this may result in systematic under- or overreporting of early behavioral problems, Kessler (1994) has set precedence for using self-reports to determine age of onset of mental disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Second, because it is almost impossible to randomly sample runaway and homeless adolescent populations (Wright, Allen, & Devine, 1995), these data are not based on a probability sample. The data were collected from multiple sites in the Midwest, which increased the reliability and generalizability of these data. Finally, cross-sectional data are used in this study, which may raise questions about causal relationships hypothesized in the structural equation model. For example, the causal direction between victimization and delinquent behavior may be reversed, as some literature suggests that victimization among street girls may lead to gang affiliation, which increases the frequency of delinquent behavior (Nurge & Shively, 2002). However, as Sampson and his colleagues suggested (Lauritsen et al., 1991; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1990), victimization may be in large part because of the exposure to dangerous situations such as involvement in delinquent behavior or crime. The causal direction needs to be further clarified from empirical support of future longitudinal studies.

Despite these limitations, this study offers important empirical contributions. Hagan and McCarthy (1997) suggested that situational adversity such as lack of housing, money, and food as well as embeddedness in street social networks increases adolescents’ involvement in delinquency and crime. Although our study provides support for this argument, our results also suggest that the elevated levels of delinquency and victimization observed among homeless youth are not simply a function of homelessness-related problems and experiences; instead, individual propensity such as childhood-onset CD helps to account for some of the observed variations. Furthermore, disruptive behavior during childhood may have cumulative effects on other life dimensions, which enhance the probability of future antisocial behavior and street victimization during adolescence.

Our study provides insight for prevention and treatment programs for homeless and runaway adolescents. Although more longitudinal studies are needed, this study suggests classifying childhood versus adolescent onset of CD among homeless and runaway adolescents may improve our understanding of heterogeneity of their antisocial behavior. Adolescents with early onset of CD create unique challenges for agency staff because they may not seek help or utilize the services that are provided but rather continue on a destructive trajectory. In addition to providing support services for homeless/runaway youth, it may also be necessary to address the problem indirectly by screening for and addressing the needs of early-onset CD youth.

Despite the theoretical and empirical importance of this study, the nature of cross-sectional data suggests that longitudinal studies are needed to examine the long-term effects of childhood conduct problems such as chronic homelessness and more severe antisocial behavior. In addition, future studies need to examine how the “snares” of being “homeless,” especially the social network of street peers and attitudes toward deviance/crime learned from the street, affects the timing of desistance of delinquency/crime among homeless adolescent-onset offenders, as well as childhood-onset offenders.

Table A2.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of All Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Onset of conduct disorder | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. Age | .08 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. Gendera | .16** | .19** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. Physical abuse | .13* | .11 | −.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. Sexual abuse | .03 | .11 | −.31** | .19** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. Age on own | −.07 | .07 | .03 | −.11 | −.04 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. Ever on the street | .01 | .34** | .22** | .21** | .06 | .00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. Deviant peers | .12* | .11 | .00 | .16** | .18** | −.12* | .16** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. Nonsexual strategies | .20** | .18** | .26** | .13** | .01 | .00 | .42** | .33** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. Sexual strategies | .11 | .21** | −.05 | .06 | .14* | −.02 | .20** | .29** | .18** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. Sexual victimization | −.03 | .04 | −.38** | .18** | .36** | −.11 | .04 | .24** | .08 | .20** | 1.00 | |

| 12. Physical victimization | .16** | .36** | .12* | .28** | .20** | −.14* | .38** | .35** | .41** | .27** | .20** | 1.00 |

| M | 0.59 | 17.36 | 0.46 | 1.35 | 0.25 | 13.76 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 1.36 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.68 |

| SD | 0.49 | 1.06 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 2.19 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 1.42 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

Note: N = 290.

1 = male.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 57110), Les Whitbeck, Principal Investigator. The authors thank Dr. Timothy Brezina for his helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Appendix

Table A1.

Distribution of Conduct Disorder Diagnostic Criteria

| Items | % |

|---|---|

| Aggression to people and animals | |

| Ever bullies, threatens, or intimidates others | 63 |

| Ever initiates physical fights | 52 |

| Has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others | 42 |

| Has been physically cruel to people | 8 |

| Has been physically cruel to animals | 18 |

| Has stolen while confronting a victim | 12 |

| Has forced someone into sexual activity | 1 |

| Destruction of property | |

| Has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage | 37 |

| Has deliberately destroyed others’ property | 56 |

| Deceitfulness or theft | |

| Has broken into someone else's house, building, or car | 35 |

| Often lies to obtain goods or favors or to avoid obligations | 73 |

| Has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim | 84 |

| Serious violations of rulesa | |

| Often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13 | 28 |

| Is often truant from school, beginning before age 13 | 34 |

Note: N = 428

One criterion, “running away from home overnight at least twice while living in parental or parental surrogate home” was excluded from the criteria because of the nature of this sample.

Contributor Information

Xiaojin Chen, Tulane University.

Lisa Thrane, Wichita State University.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. APA; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. 660 runaway boys: Why boys desert their homes. R. G. Badger; Boston: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. A psychoneurotic reaction of delinquent boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1937;32:329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. Street youths and substance use: The role of background, street lifestyle, and economic factors. Youth & Society. 1999;31:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. Self-control, social consequences and criminal behavior: Street youth and the general theory of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40:403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Baron S, Hartnagel T. Attribution, affect, and crime: Street youths’ reaction to unemployment. Criminology. 1997;35:409–434. [Google Scholar]

- Baron SW, Kennedy LW, Forde DR. Male street youths’ conflict: the role of background, subcultural, and situational factors. Justice Quarterly. 2001;18:759–789. [Google Scholar]

- Baum AS, Burnes DW. A nation in denial: The truth about homelessness. Westview; Boulder, CO: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J, Bassuk E. Mental disorders and service utilization among youths from homeless and low-income housed families. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:890–990. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR. Practical methods for counting homeless people: A manual for state and local jurisdictions. 2nd ed. Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Paradise M, Ginzler JA. The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: Age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 2000;8:230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, Felson M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:588–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, Kluegel JR, Land KC. Social inequality and predatory criminal victimization: An exposition and test of a formal theory. American Sociological Review. 1981;46:505–524. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Loever R, Elliott DS, Hawkins DJ, Kandel DB, Klein MW, et al. Advancing knowledge about the onset of delinquency and crime. In: Lahey B, Kazdin A, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 13. Plenum; New York: 1990. pp. 231–342. [Google Scholar]

- Feitel B, Margetson N, Chamas J, Lipman C. Psychosocial background and behavioral and emotional disorders of homeless and runaway youth. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1992;43:155–159. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Asdigian NL. Risk factors for youth victimization: Beyond a lifestyle/routine activities theory approach. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. Family dysfunction and the disruptive behavior disorders: A review of recent empirical findings. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 16. Plenum; New York: 1994. pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt M, Robertson MJ. Life-styles, adaptive strategies, and sexual behaviors of homeless adolescents. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:1177–1180. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.12.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, McCarthy B. Mean streets: Youth crime and homelessness. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Gottfredson MR, Garofalo J. Victims of personal crime. Ballinger; Cambridge, MA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Lahey BB, Hart EL. Issues of taxonomy and comorbidity in the development of conduct disorder. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen GF, Brownfield D. Gender, lifestyles, and victimization: Beyond routine activity. Violence and Victims. 1986;1:85–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenson P, Roper M, Fisher P, Piacenti J, Camino G, Richters J, et al. Test–retest reliability of the diagnostic interview schedule for children DISC.2.1. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:67–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130061007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KD, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Predictors of social network composition among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:231–248. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The U.S. National Comorbidity Survey: Onset, chronicity and comorbidity patterns of mood disorders in the general population. In: Langer SZ, Brunello N, Racagni G, Mendlewicz J, editors. Critical issues in the treatment of affective disorders. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 1994. pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Simon TR, Montgomery SB, Unger JB, Iverson EF. Homeless youth and their exposure to and involvement in violence while living on the streets. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;20:360–367. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel P, Burnam M, Morton J. Enumerating homeless people: Alternative strategies and their consequences. Evaluation Review. 1996;20:378–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kuder G, Richardson ME. The theory of the estimation of test reliability. Psychometrika. 1937;2:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Loeber R, Quay HC. Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of conduct disorder based on age of onset. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL, Sampson RJ, Laub JH. The link between offending and victimization among adolescents. Criminology. 1991;29(2):265–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BA, Schreck CJ. Danger on the streets: Marginality and victimization among homeless people. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48:1055–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. The stability of antisocial and delinquent child behavior: A review. Child Development. 1982;53:1431–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R. Violence and the life course: The consequences of victimization for personal and social development. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy B, Hagan J, Martin MJ. In and out of harm's way: Violent victimization and the social capital of fictive street families. Criminology. 2002;40:831–865. [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill PA, Toro PA, Wolfe SM. Homeless and matched housed adolescents: A comparative study of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;29:306–319. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993a;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993b;5:135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent offending: A complementary pair of developmental theories. In: Thornberry T, editor. Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1997. pp. 11–54. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescent-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva P, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history from age 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Lynam D. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder and delinquency: implications for understanding antisocial behavior. Progress in Experimental Personality and Psychopathology Research. 1992;15:233–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LL, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. second edition Author; Los Angeles, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nurge DM, Shively M. The role of victimization in criminal offending of female youth gangs. In: Sgarzi JM, McDevitt J, editors. Victimology. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2002. pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Stability of aggressive reaction patterns in males: A review. Psychological Review. 1979;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family interactions. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercion as a basis for early age of onset for arrest. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1995. pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Yoerger K. A developmental model for late-onset delinquency. In: Dienstbier R, Osgood DW, editors. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 44, Motivation and delinquency. Series Ed. Vol. Ed. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1997. pp. 119–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay HC. The psychobiology of undersocialized aggressive conduct disorder: A theoretical perspective. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5:165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, O'Neal P. The adult prognosis for runaway children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1959;29:752–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1959.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL. Deviant lifestyle, proximity to crime, and the offender-victim link in personal violence. Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency. 1990;27:110–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, Cohen P, Piacentini J, Davies M, et al. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version DISC-R: I. Preparation field testing interrater reliability and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:643–650. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ. Criminal victimization and low self-control: An extension and test of a general theory of crime. Justice Quarterly. 1999;16:633–654. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ, Fisher BS. Specifying the influence of family and peers on violent victimization: Extending routine activities and lifestyles theories. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1021–1041. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck CJ, Wright RA, Miller JM. A study of individual and situational antecedents of violent victimization. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, Piacentini J, Schaffer D, Davies M, Briggs-Gowan M. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version DISC-R: II. Test–retest reliability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:651–657. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Elifson KW, Sterk CE. Integrating the general theory of crime into an explanation of violent victimization among female offenders. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21:159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. The effects of early sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among female homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt LB, Whitbeck LB, Cauce AM. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among runaway youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Kipke MD, Simon TR, Johnson CJ, Montgomery SB, Iverson E. Stress, coping, and social support among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1998;13:134–157. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein S, Noam G, Grimes K, Stone K, Schwab-Stone M. Convergence of DSM-III diagnoses and self-reported symptoms in child and adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;19:627–634. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Tyler KA, Johnson KD. Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41:329–342. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Nowhere to grow: Homeless and runaway adolescents and their families. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Yoder K, Cauce AM, Paradise M. Deviant behavior and victimization among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1175–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Whitback LB, Simons KL. Life on the streets: The victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth & Society. 1990;22:108–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wittebrood K, Nieuwbeerta P. Criminal victimization during one's life course: the effects of previous victimization and patterns of routine activities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2000;37:91–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wright JD, Allen TL, Devine JA. Tracking non-traditional populations in longitudinal studies. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1995;18:267–277. [Google Scholar]