Abstract

Trimethylguanosine synthase (Tgs1) is the enzyme that converts standard m7G caps to the 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (TMG) caps characteristic of spliceosomal small nuclear RNAs. Fungi and mammalian somatic cells are able to grow in the absence of Tgs1 and TMG caps, suggesting that an essential function of the TMG cap might be obscured by functional redundancy. A systematic screen in budding yeast identified nonessential genes that, when deleted, caused synthetic growth defects with tgs1Δ. The Tgs1 interaction network embraced proteins implicated in small nuclear ribonucleoprotein function and spliceosome assembly, including Mud2, Nam8, Brr1, Lea1, Ist3, Isy1, Cwc21, and Bud13. Complementation of the synthetic lethality of mud2Δ tgs1Δ and nam8Δ tgs1Δ strains by wild-type TGS1, but not by catalytically defective mutants, indicated that the TMG cap is essential for mitotic growth when redundant splicing factors are missing. Our genetic analysis also highlighted synthetic interactions of Tgs1 with proteins implicated in RNA end processing and decay (Pat1, Lsm1, and Trf4) and regulation of polymerase II transcription (Rpn4, Spt3, Srb2, Soh1, Swr1, and Htz1). We find that the C-terminal domain of human Tgs1 can function in lieu of the yeast protein in vivo. We present a biochemical characterization of the human Tgs1 guanine-N2 methyltransferase reaction and identify individual amino acids required for methyltransferase activity in vitro and in vivo.

The 5′ m7GpppN cap structure is the defining feature of eukaryal mRNAs. Caps are formed on nascent RNA polymerase II transcripts by a three-step pathway in which the 5′-triphosphate end of the primary transcript is hydrolyzed to a diphosphate, then capped by transfer of GMP from GTP to the diphosphate RNA end to form a blocked GpppRNA end, and methylated at the cap guanine-N7 using AdoMet4 as the donor. The reactions are catalyzed by the enzymes RNA triphosphatase, RNA guanylyltransferase, and RNA (guanine-N7)-methyltransferase, respectively (1). Genetic manipulations in model organisms or cultured cells have established the universal requirement for mRNA guanylylation for viability, reflecting the fundamental role of the cap in facilitating translation initiation and protecting the 5′ RNA end from exonucleolytic decay (2–8).

Hypermethylated 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (TMG) cap structures are characteristic of small nuclear and nucleolar RNAs that program pre-mRNA splicing (U1, U2, U4, and U5), pre-rRNA processing (U3 and U8), and telomere addition (telomerase RNA) (9–11). TMG is formed post-transcriptionally from m7G caps by the enzyme Tgs1, which catalyzes two successive methyl transfer reactions from AdoMet to the N-2 atom of guanosine (12–14). Tgs1 was initially identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a two-hybrid screen for proteins that interact with SmB, an essential protein component of yeast snRNPs (12). The presence of an AdoMet-binding motif in the Tgs1 polypeptide was the tip-off that this might be the cap trimethylating enzyme. Green fluorescent protein-tagged Tgs1 is localized within the nucleolus of S. cerevisiae cells (12). Biochemical characterization of Tgs1 homologs from fission yeast and Giardia lamblia established that Tgs1 sufficed for guanine-N2 methylation in vitro absent any other protein or RNA components (14–16). Tgs1 activity is strictly dependent on prior guanine-N7 methylation, thereby restricting its activity to RNAs that already have a m7G cap. Tgs1 is nonessential for growth of budding and fission yeasts (12, 16). Schizosaccharomyces pombe tgs1Δ grows normally, notwithstanding the absence of TMG caps on its U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs (16). The equivalent tgs1Δ mutation of S. cerevisiae causes a growth defect at cold temperatures, although tgs1Δ cells grow as well as TGS1 cells at 34 °C (12). These results are surprising, given that TMG caps decorate so many important cellular RNAs.

The Tgs enzymes of budding and fission yeast and Giardia are relatively small polypeptides (239–315 amino acids) consisting of little more than a C-terminal methyltransferase catalytic domain. By contrast, metazoan Tgs1 proteins are much larger (e.g. 853 aa in humans; 491 aa in Drosophila) because they include an N-terminal extension not found in lower eukarya. Mammalian Tgs1 is distributed diffusely in the cytoplasm and locally in the nucleus, where it is concentrated in Cajal bodies (17). Tgs1 depletion by RNA interference in HeLa cells, which reduced Tgs1 mRNA levels to 8% of the control value and Tgs1 protein levels to below the limit of detection, had no effect on cell growth (18). This result suggests that mammalian somatic cells, like fungi, do not require TMG modifications for viability. On the other hand, TMG synthesis plays an essential role during Drosophila development, insofar as mutations in the Tgs1 methyltransferase active site caused lethality at the early pupal stage, which correlated with depletion of TMG-containing RNAs (19).

How can we reconcile the conservation of TMG structures on eukaryal small RNAs with the ability of somatic cells to grow in the absence of Tgs1 and TMG caps? Conceivably, TMG caps might be important for cellular physiology under environmental conditions that are not interrogated by routine laboratory growth assays. Alternatively, there might be backup pathways that ensure the function of TMG-capped RNAs when the TMG modification is missing. Here we explore the latter idea via synthetic enhancement genetics (20–23), entailing the screening of a large collection of nonessential yeast genes for ones that, when deleted, are lethal or elicit an enhanced growth defect in a tgs1Δ strain background. The validated ensemble of synthetic genetic interactions with tgs1Δ is notable for its emphasis on yeast proteins involved in either of the following: (i) snRNP biogenesis and function in pre-mRNA splicing; (ii) meiosis-specific splicing; (iii) regulation of RNA polymerase II transcription; and (iv) RNA end-processing and decay.

We exploited the synthetic lethality of tgs1Δ in the absence of splicing factors Nam8 or Mud2 to establish a complementation assay for the human Tgs1 ortholog. Deletion analyses with genetic and biochemical readouts established the minimal functional domain of hTgs1 residing at the C terminus. Alanine scanning of conserved residues delineated likely constituents of the active site. The tight correlation between TMG synthase activity in vitro and cell growth highlights that the TMG cap structure, rather than the Tgs1 protein or its imputed protein-protein interactions, is essential when one of the backup pathways is disabled.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains—The query strain Y10943 (tgs1Δ::natMX) for synthetic gene array analysis was generated by PCR-mediated gene deletion in strain Y7092 (MATa can1Δ::STE2pr-Sp_his5 lyp1Δ his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 LYS2). In brief, a tgs1Δ::natMX deletion cassette was synthesized by PCR amplification of the natMX cassette (24) in plasmid p4339 (20) using oligonucleotides tgs1-natF (5′-GTGGGGGCAACAGACAGAAGTAGAAGAAAAAATTTTT-GTTGATTTAACTGAAGTGACATGGAGGCCCAGAATACCCT) and tgs1-natR (5′-CATTCATAACATAGTCATTGCATTTTCTATCATACGATTCAACTTGAACAAGTGTCAGTATAGCGACCAGCATTCAC). The PCR product (∼1.3 kb) was introduced into Y7092 by lithium acetate transformation (25) and nourseothricin-resistant (natR) transformants were selected on YPD agar medium containing clonNAT (100 mg/liter; Werner BioAgents, Jena, Germany). Correct integration of natMX at the TGS1 locus was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Genetic Analysis—Synthetic gene array analysis was carried out in an automated format as described (20, 22) by using Y10943 (tgs1Δ::natMX) as the query strain. Three iterations of the screen were performed. The synthetic interactions between tgs1Δ and 23 of the highest scoring single-deletion mutants were tested manually by tetrad dissection at 30 °C. Twenty one “SWT” genes (Table 1) were thereby validated as being “synthetic with tgs1,” i.e. we were either unable to recover viable natR kanR “tgs1Δ swtΔ” haploid progeny (synthetic lethal; n = 2) or else the viable natR kanR tgs1Δ swtΔ haploids grew slowly at one or more temperatures tested (synthetic sick, n = 19). The growth phenotypes of the 19 synthetic sick tgs1Δ swtΔ double mutants were compared with those of the respective individual deletion mutants by spotting 2-μl aliquots of serial 10-fold dilutions of yeast cultures (grown to mid-log phase in YPD broth at 30 °C and adjusted to A600 of 0.1) to YPD agar medium and then incubating the plates at various temperatures. To verify synthetic lethality of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ and tgs1Δ nam8Δ double mutants that were not recovered in the initial tetrad dissections, the heterozygous diploid strains were transformed with plasmid p360-TGS1 (CEN URA3 TGS1) (see below) and then subjected to tetrad analysis. All of the viable natR kanR haploid progeny were Ura+ (i.e. they contained the URA3 TGS1 plasmid), and they failed to grow on agar medium containing 0.75 mg/ml 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA), a drug that selects against the URA3 plasmid. Strains yTM (MATa tgs1Δ mud2Δ p360-TGS1) and yTN (MATa tgs1Δ nam8Δ p360-TGS1) were used for plasmid shuffle complementation assays of yeast and human Tgs1 function in vivo.

TABLE 1.

Synthetic interactors with Tgs1

| Category | Tgs1 interactor | Properties | Other in-group interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA splicing | Mud1 | U1 snRNP A protein | Nam8, Lea1, Brr1 |

| Mud2 | U2AF65 homolog spliceosome assembly | Ist3 | |

| Nam8 (Mud15) | U1 snRNP protein meiosis-specific splicing | Mud1, Lea1 | |

| Brr1 | snRNP protein | Mud1 | |

| Lea1 | U2 snRNP protein | Nam8, Mud1, Isy1, Rpn4 | |

| Ist3 (Snu17) | U2 snRNP protein meiosis-specific splicing | Bud13, Mud2, Htz1, Swr1 | |

| Isy1 (Ntc30) | Spliceosome protein Prp19-complex | Lea1 | |

| Cwc21 | Cef1 complex | Htz1 | |

| Bud13 (Cwc26) | Cef1, RES complexes meiosis-specific splicing | Ist3, Lsm1, Pat1, Swr1, Htz1 | |

| Transcription | Rpn4 | Transcription factor stress response | Swr1, Htz1, Soh1, Lsm1, Lea1, Prm6 |

| Spt3 | Transcription factor SAGA complex | Htz1, Swr1, Srb2, Soh1, Pat1, Lsm1 | |

| Srb2 | Pol2 mediator complex | Spt3, Soh1, Swr1, Htz1, Pat1 | |

| Soh1 (Med31) | Pol2 mediator complex | Srb2, Swr1, Rpn4, Htz1, Spt3, Pat1 | |

| Swr1 | Chromatin remodeling ATPase; deposition of H2A.Z | Htz1, Soh1, Spt3, Rpn4, Pat1, Trf4, Bud13 | |

| Htz1 | Histone H2A.Z | Swr1, Spt3, Rpn4, Trf4, Pat1, Bud13, Ist3 | |

| RNA stability | Lsm1 | Decapping, RNA decay | Pat1, Spt3, Bud13, Rpn4 |

| Trf4 (Pap2) | Poly(A) polymerase TRAMP complex | Htz1, Swr1, Soh1 | |

| Pat1 | Decapping, RNA decay P-body component | Lsm1, Srb2, Bud13, Spt3, Soh1, Htz1 | |

| Other | Prm6 | Pheromone-regulated protein | Rpn4 |

| Mrm2 | RNA 2′-O-methyltransferase | – | |

| Ynl187w (Swt21) | Interactions with snRNP proteins Prp40 and SmB | – |

Yeast Expression Plasmids—A DNA segment comprising the open reading frame encoding S. cerevisiae Tgs1 plus 345 and 201 bp of upstream and downstream DNA, respectively, was amplified by PCR from yeast genomic DNA using primers designed to introduce EcoRI and SmaI sites at the termini. The 1.5-kbp PCR product was digested and ligated into appropriately restricted pSE360 and pUN100 shuttle vectors to generate plasmids p360-TGS1 (CEN URA3 TGS1) and pUN100-TGS1 (CEN LEU2 TGS1). Alanine mutations were introduced into the TGS1 gene by two-stage PCR with mutagenic primers, and the mutated DNA fragments were inserted into pUN100. The inserts of all clones were sequenced to exclude the presence of unwanted mutations. For expression of the human TGS1 gene in yeast, BamHI-XhoI fragments were excised from bacterial hTgs1 expression vectors (see below) and inserted into pRS425-TPI1-B, a modified version of pRS425 (2μ LEU2) that contains a 2.2-kb PvuII fragment from pYX132 (Novagen) bearing a yeast TPI1 promoter that drives transcription of the hTGS1 insert. The hTGS1-(576–853) allele was introduced in a similar fashion into a CEN LEU2 vector (pRS415-TPI1-B) under the control of the TPI1 promoter.

Bacterial Expression Vectors for hTgs1—The open reading frame encoding hTgs1 was amplified from a human B lymphoid cDNA library by PCR with primers designed to introduce a BamHI site at the start codon and an XhoI site 3′ of the stop codon. The primary structure of the 853-aa polypeptide encoded by the resulting cDNA was identical to that of hTgs1 deposited in NCBI data base under accession number Q96RS0. The N-terminal deletion mutants hTgs1-(576–853), hTgs1-(607–853), hTgs1-(631–853), and hTgs1-(662–853) were constructed by PCR amplification with sense strand primers that introduced a BamHI restriction site and a methionine codon in lieu of the codons for Ser-575, Glu-606, Lys-630, or Gly-661 and an antisense strand primer that introduced an XhoI site 3′ of the stop codon. A series of C-terminal deletions was constructed by PCR amplification with antisense primers that introduced stop codons in place of the codons for Pro-806, Ser-816, Asn-832, Tyr-841, or Arg-847 and an XhoI site 3′ of the new stop codon. Alanine mutations were introduced into the hTgs1-(631–853) gene fragment by PCR amplification with mutagenic primers. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI and then ligated into BamHI/XhoI-cut plasmid pET28-His10Smt3, so as to fuse the hTgs1 proteins in-frame with an N-terminal His10Smt3 tag. The plasmid inserts were sequenced completely to exclude the acquisition of unwanted mutations during amplification and cloning.

Recombinant hTgs1—The pET28-His10Smt3-hTgs1 plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Cultures (500 ml) derived from single transformants were grown at 37 °C in LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin until the A600 reached 0.6. The cultures were adjusted to 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and 2% (v/v) ethanol, and incubation was continued for 20 h at 17 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at -80 °C. All subsequent procedures were performed at 4 °C. Thawed bacteria were resuspended in 25 ml of buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol) and supplemented with 1 tablet of protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The suspension was adjusted to 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme and incubated on ice for 30 min. Imidazole was added to a final concentration of 5 mm, and the lysate was sonicated to reduce viscosity. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The soluble extracts were mixed for 30 min with 1.6 ml of Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) that had been equilibrated with buffer A containing 5 mm imidazole. The resins were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in buffer A with 5 mm imidazole, and poured into columns. The columns were washed with 8-ml aliquots of 10 and 20 mm imidazole in buffer A and then eluted stepwise with 2.5-ml aliquots of buffer A containing 50, 100, 250, and 500 mm imidazole. The elution profiles were monitored by SDS-PAGE. The 250 mm imidazole eluates containing the hTgs1 polypeptides were dialyzed against buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol and then stored at -80 °C. The protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad dye reagent with BSA as the standard. Alternatively, the concentrations of some alanine mutants were determined by SDS-PAGE analysis of the hTgs1 preparations in parallel with serial dilutions of a BSA standard. The gels were stained with Coomassie Blue, and the staining intensities of the hTgs1 and BSA polypeptides were quantified using Bio-Rad digital imaging and analysis system. hTgs1 concentrations were calculated by interpolation to the BSA standard curve.

Methyltransferase Assay—Reaction mixtures containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 5 mm dithiothreitol, m7GDP as specified, [3H-CH3]AdoMet as specified, and enzyme were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Aliquots (4 μl) were spotted on PEI-cellulose TLC plates, which were developed with 50 mm ammonium sulfate. The AdoMet- and m2,7G-containing portions of the lanes were cut out, and the radioactivity in each was quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

Glycerol Gradient Sedimentation—An aliquot (50 μg) of the nickel-agarose preparation of hTgs1-(576–853) was mixed with catalase (45 μg), bovine serum albumin (45 μg), and cytochrome c (45 μg). The mixture was applied to a 4.8-ml 15–30% glycerol gradient containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.25 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 2 mm dithiothreitol. The gradient was centrifuged for 20 h at 4 °C in a Beckman SW50 rotor at 48,000 rpm. Fractions (0.17 ml) were collected from the bottom of the tube.

RESULTS

Genome-wide Screen for Mutation Synergy with tgs1Δ—Synthetic genetic array analysis was performed by mating a haploid S. cerevisiae tgs1::natR strain resistant to nourseothricin with a collection of ∼4700 viable haploid deletion mutants in which single nonessential genes are disrupted by a kanR marker. The resulting diploids were sporulated, and kanamycin-resistant MATa haploids were selected and then screened for growth on medium containing nourseothricin. The operations were performed robotically, and the growth of the double mutant progeny was scored by automated digital imaging and measurements of colony size (20). Three iterations of the interaction screen yielded candidates that met statistical criteria for synthetic lethality or synthetic enhancement of tgs1Δ. To validate the screen, the heterozygous diploids containing tgs1Δ and the highest scoring candidate gene deletions were subjected to sporulation and manual tetrad analysis. We thereby found synthetic lethality between tgs1Δ and deletions in two yeast genes encoding pre-mRNA splicing factors (Mud2 and Nam8), i.e. no haploid tgs1Δ mud2Δ and tgs1Δ nam8Δ progeny could be recovered at 30 °C. Nineteen other heterozygotes gave rise to viable doubly deleted haploids after sporulation, but, as shown below, the double mutants displayed growth defects more severe than either single deletion mutant. These 19 strains exemplified synthetic enhancement.

The 21 synthetic interactors with Tgs1 are listed in Table 1 and grouped according to their known or imputed functions. Nine of the verified interactors were proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing: Mud1, Mud2, Nam8, Brr1, Lea1, Ist3 (also known as Snu17), Isy1, Cwc21, and Bud13 (Cwc26). Of these nine, two (Mud1 and Nam8) are constituents of the U1 snRNP, and two others (Lea1 and Ist3) are components of the U2 snRNP. It is surely no coincidence that the synthetic genetic array analysis identified functional redundancy between Tgs1, the enzyme required for TMG cap formation, and proteins that assemble on the TMG-containing U1 and U2 snRNAs. Other Tgs1 interactors fall into two functional categories pertinent to RNA transactions. Six are implicated in regulation of RNA polymerase II transcription and/or chromatin structure as follows: Spt3, Srb2, Soh1, Swr1, Rpn4, and Htz1. Three others are implicated in RNA end processing and decay as follows: Lsm1, Pat1, and Trf4 (also known as Pap2) (Table 1).

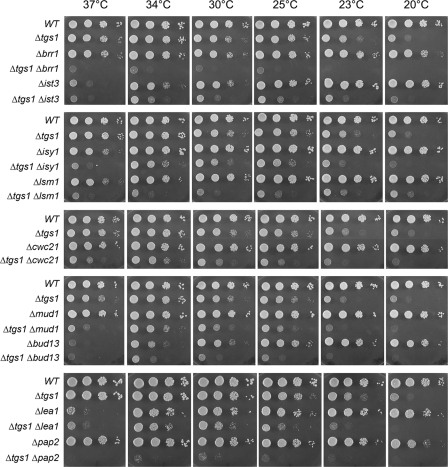

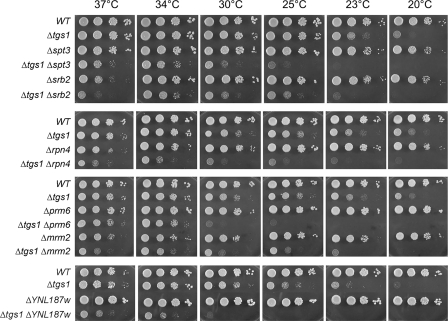

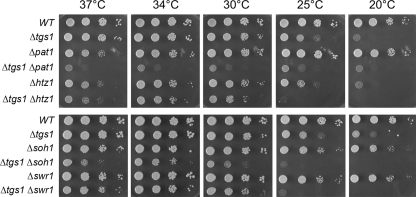

Synthetic Enhancement of Growth Phenotypes—The growth properties of the viable double-deletion strains were evaluated by spotting serial dilutions of cells (from liquid mid-log phase cultures adjusted to A600 of 0.1) on YPD agar medium and screening for growth at temperatures ranging from 20 to 37 °C. Wild-type cells and the pertinent single-deletion strains were tested in parallel (Figs. 1, 2, 3). The tgs1Δ single mutant displayed a slow-growth phenotype at low temperatures (20–23 °C) but grew well at 25–37 °C. Severe genetic enhancement was seen with brr1Δ, a mutation that had little effect per se on growth at 23–37 °C but resulted in barely detectable growth at 25–37 °C when combined with tgs1Δ (Fig. 1). Similarly, severe mutational enhancement was noted when tgs1Δ was combined with lsm1Δ, pap2Δ, pat1Δ, rpn4Δ, and YNL187wΔ (Figs. 1, 2, 3). Other genetic interactions were evinced by absent or slowed growth of the respective double-deletion mutants at particular temperatures. This was the case for ist3Δ (at 25, 30, and 34 °C), spt3Δ (23, 25, 30, and 37 °C), srb2Δ (23, 25, 30, and 37 °C), bud13Δ (25 and 30 °C), lea1Δ (23 and 25 °C), prm6Δ (23, 25, and 30 °C), mrm2Δ (25, 30, and 37 °C), soh1Δ (25, 30, and 37 °C), cwc21Δ (37 °C), mud1Δ (37 °C), isy1Δ (37 °C), swr1Δ (25 °C), and htz1Δ (25 °C) (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

FIGURE 1.

Mutational synergy of tgs1 with genes involved in splicing and RNA decay. Aliquots (2 μl) of serial 10-fold dilutions of haploid yeast strains of the specified genotypes were spotted on YPD agar medium. The plates were photographed after incubation for 2 days (37, 34, and 30 °C), 3 days (25 and 23° C), or 4 days (20 °C) as specified.

FIGURE 2.

Mutational synergy of tgs1, including genes involved in transcription. Aliquots (2 μl) of serial 10-fold dilutions of haploid yeast strains of the specified genotypes were spotted on YPD agar medium. The plates were photographed after incubation for 2 days (37, 34, and 30 °C), 3 days (25 and 23° C), or 4 days (20 °C) as specified.

FIGURE 3.

Mutational synergy of tgs1 with genes involved in RNA stability and transcription. Aliquots (2 μl) of serial 10-fold dilutions of haploid yeast strains of the specified genotypes were spotted on YPD agar medium. The plates were photographed after incubation for 2 days (37, 34, and 30 °C), 3 days (25 °C), or 4 days (20 °C) as specified.

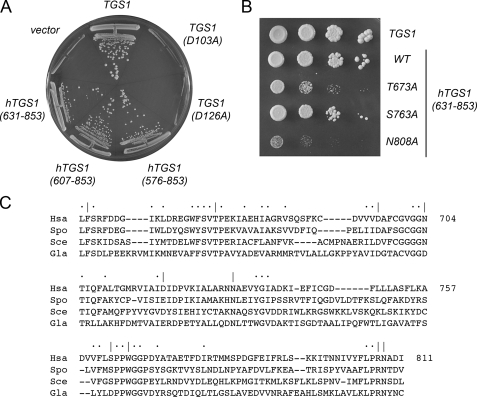

Complementation of the Synthetic Lethality of tgs1Δ mud2Δ and tgs1Δ nam8Δ by TGS1 Depends on the Tgs1 Methyltransferase Activity—The mud2Δ and nam8Δ single mutants grew as well as the wild-type strain at 18, 30, and 37 °C, as gauged by colony size (data not shown). By contrast, the mud2Δ tgs1Δ and nam8Δ tgs1Δ double mutations were lethal. To rescue the lethality of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ double mutant, we transformed the diploid TGS1 tgs1Δ MUD1 mud1Δ heterozygote with a CEN URA3 plasmid containing the wild-type TGS1 gene under the control of its native promoter. The Ura+ diploids were then sporulated, and tetrads were dissected. We thereby derived viable haploid tgs1::natR mud2::kanR progeny, all of which were Ura+. These cells were dependent on the plasmid-borne TGS1 gene for viability, insofar as they were unable to grow on medium containing FOA, a drug that selects against the CEN URA3 TGS1 plasmid (Fig. 4A). We found that transformation of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ p(URA3 TGS1) strain with a CEN LEU2 TGS1 plasmid permitted growth on FOA (Fig. 4A) because the presence of the second plasmid-borne TGS1 gene allowed for loss of the URA3 TGS1 plasmid. Having established a plasmid shuffle assay that provides a readout of essential Tgs1 functions, we queried whether Tgs1 methyltransferase activity was required for viability of mud2Δ cells, by performing the plasmid shuffle complementation test with Tgs1 mutants in which conserved aspartates of the AdoMet-binding site (Asp-103 and Asp-126 in S. cerevisiae Tgs1) were replaced with alanine. Previous studies of fungal and Giardia Tgs proteins had shown that such alanine substitutions abolish guanine-N2 methyltransferase activity in vitro and TMG cap formation in vivo (12, 15, 16). Here we found that the D103A and D126A alleles failed to complement the mud2Δ tgs1Δ strain (Fig. 4A). These results were reprised when we tested complementation of a nam8Δ tgs1Δ p(URA3 TGS1) strain with the same set of CEN LEU2 plasmids bearing wild-type TGS1, D103A, or D126A alleles (not shown). We surmise that the methyltransferase activity of Tgs1, not merely the Tgs1 protein, is required for cell viability when Mud2 or Nam8 function is ablated.

FIGURE 4.

Complementation of tgs1Δ mud2Δ by yeast and human TGS1. A, yeast tgs1Δmud2Δ p360-TGS1 (URA3 CEN TGS1) cells were transformed with CEN LEU2 plasmids harboring wild-type TGS1 (positive control) or the mutant alleles D103A and D126A, and with 2μ LEU2 plasmids carrying hTGS1-(576–853), hTGS1-(607–853), or hTGS1-(631–853). Leu+ transformants were selected at 30 °C and then streaked to agar medium containing FOA. Cells transformed with the empty 2μ LEU2 vector served as a negative control. The plate was photographed after 4 days at 30 °C. B, serial 10-fold dilutions of tgs1Δmud2Δ cells harboring LEU2 plasmids with yeast TGS1 (positive control), wild-type hTGS1-(631–853), or the hTGS1-(631–853) T673A, S763A, and N808A mutant alleles were spotted on YPD agar medium. The plate was photographed after 3 days at 30 °C. C, amino acid sequence of Homo sapiens (Hsa) Tgs1 from residues 654 to 811 is aligned to the sequences of homologous polypeptides encoded by S. cerevisiae (Sce), S. pombe (Spo), and G. lamblia (Gla). Gaps in the alignment are indicated by dashes. Positions of identity/similarity in all four proteins are indicated by dots. Positions in hTgs1 that were targeted for alanine scanning are indicated by |.

Human Tgs1 Is an Ortholog of Yeast Tgs1—hTgs1 is an 853-aa polypeptide that contains a long N-terminal extension not found in yeast Tgs1. Here we exploited the synthetic lethality of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ strain to query whether hTgs1 is a true functional ortholog of yeast Tgs1. A yeast 2μ LEU2 plasmid expressing a C-terminal fragment of hTgs1 (aa 576–853) under the control of a constitutive yeast promoter was tested for complementation of tgs1Δ mud2Δ by the plasmid shuffle procedure. We found that hTGS1-(576–853) was capable of supporting colony formation on FOA-containing medium (Fig. 4A). 2μ hTGS1-(576–853) also complemented the tgs1Δ nam8Δ strain (not shown). Expression of hTGS1-(576–853) on a CEN plasmid complemented tgs1Δ mud2Δ as well as the 2μ version (not shown). Thus, the C-terminal segment of hTgs1 could fulfill the essential functions of yeast Tgs1 in the mud2Δ or nam8Δ background.

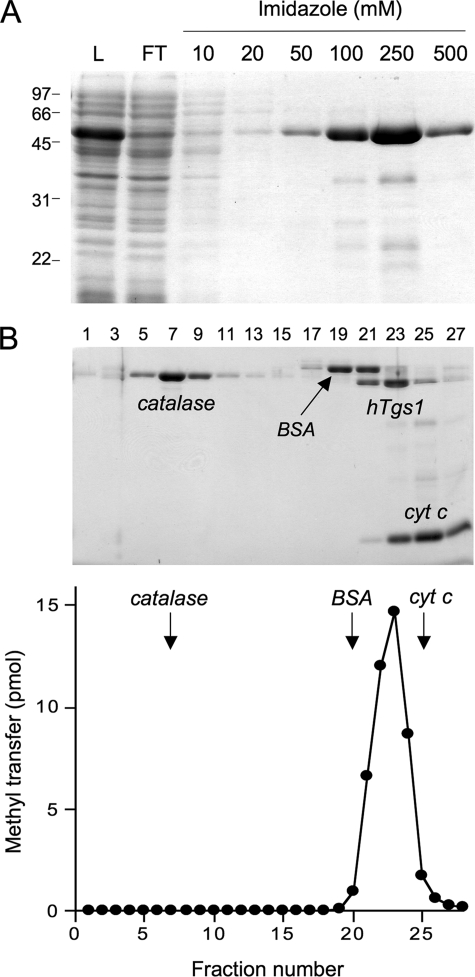

Methyltransferase Activity of Recombinant hTgs1—Having validated the biological activity of hTgs1, we sought to thoroughly characterize the enzyme biochemically. An initial effort to purify full-length hTgs1 was hampered by its intractable insolubility when produced in E. coli. By contrast, the biologically active C-terminal domain hTgs1-(576–853) was produced with reasonable yield and solubility as a His10Smt3 fusion, which was amenable to purification by Ni2+-agarose chromatography (Fig. 5A). The quaternary structure of His10Smt3-hTgs1-(576–853) was examined by zonal velocity sedimentation in a 15–30% glycerol gradient. Marker proteins catalase (native size 248 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), and cytochrome c (12 kDa) were included as internal standards in the gradient. The tagged hTgs1-(576–853) polypeptide (calculated mass of 45 kDa) sedimented as a discrete peak (fraction 21–25) between bovine serum albumin and cytochrome c (Fig. 5B). The methyltransferase activity of hTgs1-(576–853) was demonstrated by incubating the enzyme with [3H-CH3]AdoMet and m7GpppA, which resulted in label transfer from AdoMet to m7GpppA to form an anionic methylated product that was separated from the cationic AdoMet substrate by PEI-cellulose TLC in 50 mm ammonium sulfate (see below). The extent of 3H-methyl transfer by the glycerol gradient fractions paralleled the abundance of the tagged Tgs1-(576–853) polypeptide and peaked at fraction 23 (Fig. 5B, lower panel). We surmise from these results that the methyltransferase activity is intrinsic to hTgs1 and that the tagged enzyme is a monomer in solution.

FIGURE 5.

Methyltransferase activity of recombinant hTgs1-(576–853). A, purification. Aliquots (10 μl) of the soluble bacterial lysate (L), the nickel-agarose flow-through (FT), and the 10, 20, 50, 100, 250, and 500 mm imidazole eluate fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The polypeptides were visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue dye. The positions and sizes (kDa) of marker polypeptides are indicated on the left. B, velocity sedimentation was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Aliquots (18 μl) of the odd-numbered glycerol gradient fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The Coomassie Blue-stained gel is shown in the upper panel. The identities of the polypeptides are indicated. The methyltransferase activity profile is shown in the lower panel. Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 2.5 mm m7GpppA, 6.7 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, and 1.5 μl of the indicated glycerol gradient fractions were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. cyt c, cytochrome c.

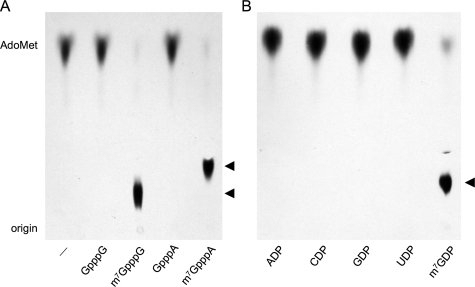

Substrate Specificity of hTgs1-(576–853)—Various nucleotides were tested as methyl acceptors at 2.5 mm concentration (Fig. 6). hTgs1-(576–853) catalyzed nearly quantitative label transfer from AdoMet to the cap dinucleotides m7GpppG and m7GpppA to form unique products (m2,7GpppG and m2,7GpppA) that were resolved from AdoMet by PEI-cellulose TLC in 50 mm ammonium sulfate (Fig. 6A). The labeled nucleotide products migrated immediately ahead of the respective input unlabeled cap dinucleotides m7GpppG and m7GpppA (not shown). Tgs1-(576–853) formed no new labeled product when reacted with unmethylated cap dinucleotides GpppG and GpppA (Fig. 6A). Thus, hTgs1 guanine-N2 methyltransferase activity with cap analogs is stringently dependent on prior guanine-N7 methylation.

FIGURE 6.

Methyl acceptor specificity of hTgs1. Methyltransferase reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, 4 μg of hTgs1-(576–853), and 2.5 mm cap dinucleotide (A) or nucleoside diphosphate (B) as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Nucleotide was omitted from the control reaction in lane -. Aliquots (4 μl) were spotted onto PEI-cellulose TLC plates. The anionic nucleotides were resolved from AdoMet by ascending TLC in 50 mm ammonium sulfate. The chromatograms were treated with Enhance (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and 3H-labeled material was visualized by autoradiography. The methyltransferase reaction products m2,7GpppG and m2,7GpppA (A) or m2,7GDP (B) are denoted by ◂.

We also tested hTgs1-(576–853) activity with a series of nucleoside diphosphates at 2.5 mm concentration. The enzyme catalyzed near quantitative methyl transfer from AdoMet to m7GDP to form a unique labeled product that comigrated with m2,7GDP during PEI-cellulose TLC in 50 mm ammonium sulfate (Fig. 6B). No new labeled product was formed in the presence of ADP, CDP, UDP, or GDP. Similar experiments with nucleoside triphosphates showed that hTgs1 methylated m7GTP but not GTP (data not shown).

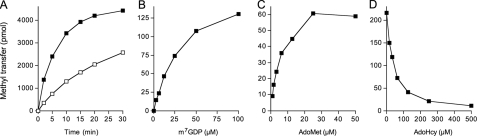

Further characterization of hTgs1-(576–853) was performed using m7GDP as the methyl acceptor. Activity was optimal in Tris buffer at pH 8.5–9.5, declined to 65% of the optimum at pH 7.0, and was nil at pH ≤5 (data not shown). The extent of methylation of m7GDP increased with time, and the initial rate was proportional to input enzyme (Fig. 7A). From these data, we estimated a turnover number of 2.7 min-1. The extent of methyl transfer in the presence of 50 μm AdoMet displayed a hyperbolic dependence on m7GDP (Fig. 7B). From a double-reciprocal plot of the data, we calculated a Km of 30 μm m7GDP and a kcat of 2.4 min-1. Methylation of 1 mm m7GDP displayed a hyperbolic dependence on AdoMet concentration (Fig. 7C); from these data, we calculated a Km of 5 μm AdoMet and a kcat of 1.9 min-1. Methylation of 1 mm m7GDP in the presence of 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet was inhibited in a concentration-dependent fashion by the reaction product AdoHcy; the apparent IC50 for AdoHcy was 40 μm (Fig. 7D). Thus, hTgs1-(576–853) has similar affinity for its substrate AdoMet and its product AdoHcy.

FIGURE 7.

Characterization of the hTgs1 methyltransferase reaction. A, kinetics. Reaction mixtures (100 μl) containing 1 mm m7GDP, 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, and either 2.5 μg (□) or 10 μg (▪) of hTgs1-(576–853) were incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots (4 μl) were withdrawn at the times indicated, and product formation was analyzed by TLC. B, m7GDP dependence. Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, 200 ng of hTgs1-(576–853), and m7GDP as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. C, AdoMet dependence. Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 1 mm m7GDP, 100 ng hTgs1-(576–853), and [3H-CH3]AdoMet as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. D, inhibition by AdoHcy. Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 1 mm m7GDP, 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, 300 ng hTgs1-(576–853), and AdoHcy as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C.

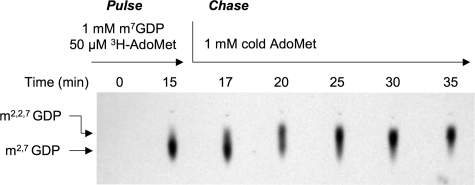

hTgs1 Can Add Two Methyl Groups at N-2 of m7GDP—The labeled product formed by Tgs1 in reactions containing excess m7GDP methyl acceptor comigrated during TLC with the m2,7GDP product synthesized by Giardia Tgs2 (a dimethylguanosine synthase; data not shown). The absence of a trimethylated m2,2,7GDP product under these conditions implies either of the following: (i) hTgs1 is not responsible for the second methylation reaction or (ii) hTgs1 does catalyze a second methylation reaction, but we are precluded from detecting it because the enzyme acts distributively, i.e. the labeled m2,7GDP product dissociates after a single round of catalysis and must compete with a large molar excess of unlabeled m7GDP for rebinding to Tgs1. Previous studies showed that S. pombe Tgs1 does catalyze sequential methylation reactions at N-2 via a distributive mechanism (14). To address these issues for the human enzyme, we performed a pulse-chase labeling experiment, as outlined in Fig. 8. During the pulse phase, hTgs1-(576–853) was reacted with 1 mm m7GDP and 50 μm [methyl-3H]AdoMet for 15 min, at which time >90% of the label had been transferred to the substrate to form m2,7GDP (Fig. 8). The chase phase was initiated by supplementing the reaction mixture with 1 mm cold AdoMet and fresh hTgs1-(576–853). Aliquots were taken at serial intervals after the addition of the cold AdoMet, and the products were analyzed by TLC. The instructive finding was that all the 3H-labeled m2, 7GDP formed during the pulse phase was subsequently converted by Tgs1 to the slightly more rapidly migrating trimethylated product m2,2,7GDP during the chase (Fig. 8). Approximately half of the pulse-labeled m2,7GDP was converted to m2,2,7GDP after 5 min of the chase phase. We surmise that hTgs1 is a trimethylguanosine synthase capable of performing two methyl addition reactions at the N-2 atom of m7G.

FIGURE 8.

Trimethylguanosine synthesis by Tgs1. A reaction mixture containing 1 mm m7GDP, 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, and 2.2 μm hTgs1-(576–853) was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C (pulse) and then supplemented with 1 mm unlabeled AdoMet and 6.8 μm hTgs1-(576–853) (chase). Aliquots (4 μl) were withdrawn at the times indicated (relative to initiation of the pulse reaction) and then spotted onto PEI-cellulose TLC plates. The products were analyzed by ascending TLC in 100 mm ammonium sulfate. The chromatogram was treated with Enhance (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and 3H-labeled material was visualized by autoradiography. The portion of the chromatogram containing the guanosine nucleotides is shown.

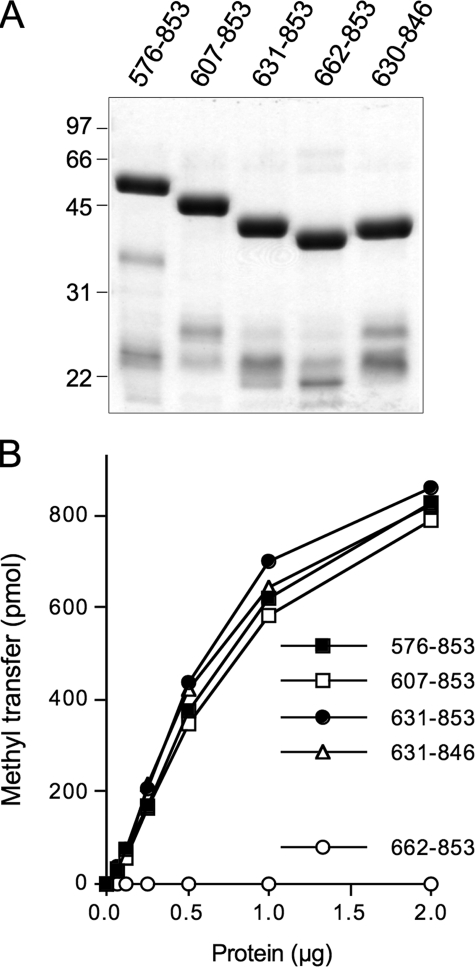

Deletion Analysis Defines a Methyltransferase Catalytic Domain—Several more extensively truncated N-terminal deletion mutants of hTgs1 were expressed in bacteria as His10Smt3 fusions and purified from soluble lysates by nickel-agarose chromatography. SDS-PAGE revealed the expected increases in electrophoretic mobility with each serial deletion (Fig. 9A). Enzyme titrations in the presence of saturating substrate concentrations (1 mm m7GDP; 50 μm [3H]AdoMet) showed that specific activities of hTgs1-(607–853) and hTgs1-(631–853) were 93 and 120% of the specific activity of hTgs1-(576–853) (Fig. 9B). We conclude that the N-terminal 630 amino acids of human Tgs1 are not required for catalysis. By contrast, hTgs1-(662–853) was catalytically inert, indicating that the segment between position 631 and 662 is essential (Fig. 9B). The two catalytically active deletions mutants, hTgs1-(607–853) and hTgs1-(631–853), were biologically active in yeast, as gauged by complementation of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ and tgs1Δ nam8Δ strains (Fig. 4A and data not shown).

FIGURE 9.

Effects of N- and C-terminal deletions on hTgs1 methyltransferase activity. A, aliquots (4 μg) of the nickel-agarose preparations of deletion mutants Tgs1-(576–853), Tgs1-(607–853), Tgs1-(631–853), Tgs1-(662–853), and Tgs1-(631–846) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Polypeptides were visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye. The positions and sizes (kDa) of marker proteins are indicated on the left. B, methyltransferase reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, 1 mm m7GDP, and hTgs1 proteins as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. The extent of methyl transfer is plotted as a function of input enzyme.

C-terminal deletion mutants hTgs1-(631–805), hTgs1-(631–815), hTgs1-(631–831), hTgs1-(631–840), and Tgs1-(631–846) were also produced in bacteria as His10Smt3 fusions. The hTgs1-(631–805), hTgs1-(631–815), hTgs1-(631–831), and hTgs1-(631–840) polypeptides were insoluble (not shown) and therefore not amenable to purification and further study. The hTgs1-(631–846) protein was soluble and readily purified (Fig. 9A). The methyltransferase-specific activity of hTgs1-(631–846) was 120% of the activity of Tgs1-(631–853) (Fig. 9B). Thus, the last seven amino acids are dispensable for catalysis.

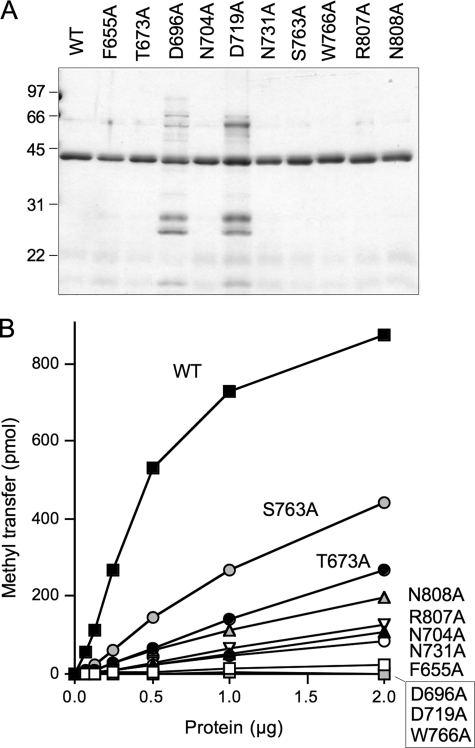

Alanine Scanning of the hTgs1 Catalytic Domain—We introduced 10 single alanine mutations into the hTgs1-(631–853) protein. The targeted residues, Phe-655, Thr-673, Asp-696, Asn-704, Asp-719, Asn-731, Ser-763, Trp-766, Arg-807, and Asn-808, are located within the minimal catalytic domain and most are conserved among Tgs homologs (Fig. 4C). The hTgs1-(631–853)-Ala proteins were produced in bacteria as His10Smt3 fusions, purified by Ni2+-agarose chromatography (Fig. 10A), and then assayed by protein titration for methyltransferase activity with m7GDP as substrate (Fig. 10B). The specific activities of the mutants relative to wild-type hTgs1-(631–853) are compiled in Table 2. Four of the mutants, F655A, D696A, D719A, and W766A, had <1% of wild-type specific activity. These findings are concordant with previously reported mutational effects at the equivalent conserved amino acids in Giardia Tgs2 (Phe-18, Asp-68, Glu-91, and Trp-143, respectively) (15, 16). The six other hTgs1-Ala mutants analyzed here displayed a hierarchy of activity decrements, from severe to moderate, as follows: N731A (4% of wild-type); N704A (5%); R807A (6%); N808A (11%); T673A (13%); and S763A (26%).

FIGURE 10.

Effects of alanine mutations on hTgs1 methyltransferase activity. A, aliquots (1 μg) of the nickel-agarose preparations of wild-type hTgs1-(631–853) and the indicated hTgs1-(631–853)-Ala mutants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Polypeptides were visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye. The positions and sizes (kDa) of marker proteins are indicated on the left. B, methyltransferase reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 μm [3H-CH3]AdoMet, 1 mm m7GDP, and hTgs1 proteins as specified were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. The extent of methyl transfer is plotted as a function of input enzyme. WT, wild type.

TABLE 2.

Mutational effects on hTgs1 activity

| hTGS1-(631–853) allele | Methyltransferase (% of wild type) | Complementation of tgs1Δ mud2Δ |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 100 | +++ |

| F655A | <1 | – |

| T673A | 13 | + |

| D696A | <1 | – |

| N704A | 5 | – |

| D719A | <1 | – |

| N731A | 4 | – |

| S763A | 26 | ++ |

| W766A | <1 | – |

| R807A | 6 | – |

| N808A | 11 | ± |

The effects of the 10 alanine mutations on hTgs1 function in vivo were gauged by plasmid shuffle assay for complementation of the tgs1Δ mud2Δ strain, entailing transformation with 2μ LEU2 plasmids bearing wild-type hTGS1-(631–853) or the various hTGS1-(631–853)-Ala alleles. The seven “lethal” alanine changes (F655A, D696A, N704A, D719A, N731A, W766A, and R807A) that abolished complementation in vivo (scored as - in Table 2, signifying no colony formation on growth on FOA-containing medium at 20, 25, 30 or 37 °C) were those mutations that caused the most severe reductions in methyltransferase activity in vitro (≤6% of wild-type). Three of the hTGS1-(631–853)-Ala alleles that gave rise to FOA-resistant tgs1Δ mud2Δ derivatives were tested for growth on YPD medium. Each displayed a slow growth phenotype compared with wild-type hTGS1-(631–853), as gauged by colony size (Fig. 4B). The severity of the growth defects correlated well with methyltransferase-specific activity in vitro, as follows: N808A (±growth; 11% activity), T673A (+growth; 13% activity), and S763A (++growth; 26% activity) (Table 2). These results underscore that hTgs1 function in the yeast complementation assay is a reflection of its TMG synthetic capacity.

DISCUSSION

Structure-Function Analysis of Human Tgs1—Previous studies of hTgs1 focused on its intracellular compartmentalization. Girard et al. (26) reported that hTgs1 exists as two species in HeLa cells as follows: (i) a full-length cytoplasmic isoform migrating at ∼110 kDa during SDS-PAGE and (ii) an ∼70-kDa nuclear isoform comprising a C-terminal proteolytic fragment. The cytoplasmic and nuclear variants have imputed roles in TMG modification of snRNAs and snoRNA, respectively (26). A GST-hTGS1-(380–853) fusion protein was produced in bacteria and judged to have methyltransferase activity (26), based on label transfer from [3H-CH3]AdoMet to m7GTP to generate a radiolabeled anionic species that adhered to a DEAE filter. However, Girard et al. (26) did not quantify the hTgs1 transmethylation activity or identify the methylated reaction product.

Here we report a comprehensive physical, biochemical, and genetic analysis of hTgs1 that advanced our understanding of this enzyme. We purified and characterized an autonomous C-terminal catalytic domain of hTgs1, spanning aa 576–853, that sufficed for two serial methyl transfer reactions as follows: conversion of m7GDP to m2,7GDP and then to m2,2,7GDP. The dimethylated and trimethylated species formed in vitro by hTgs1 were indistinguishable by TLC from the DMG and TMG nucleotides produced by S. pombe Tgs1 (data not shown) (14). The hTgs1-(576–853) enzyme readily utilized m7GpppA, m7GpppG, m7GTP, or m7GDP as the methyl acceptor, displaying a stringent requirement for the N-7 methyl group. The apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of hTgs1-(576–853) for the first guanine-N2 methylation step were as follows: Km 5 μm AdoMet, 30 μm m7GDP, and kcat 2.4 min-1. Reference to the analogous kinetic data reported for S. pombe Tgs1 (Km 8 μm AdoMet, 570 μm m7GDP; kcat 2 min-1) (14) highlights the nearly 20-fold higher affinity of human Tgs1 for the m7GDP methyl acceptor. Zonal velocity sedimentation analysis of the Smt3-tagged hTgs1-(576–853) suggested a monomeric native structure, similar to the monomeric S. pombe and Giardia Tgs enzymes (14, 15). Because we were unable to produce a recombinant version of full-length hTgs1, we do not exclude the possibility that the missing N-terminal segment might confer a more complex quaternary structure.

We defined a minimal catalytic domain of hTgs1 from aa 631 to 853 that sufficed for guanine-N2 methyltransferase activity in vitro. The N terminus of this domain is located immediately upstream of the region of primary structure conservation among members of the Tgs clade (Fig. 4C). Further truncation of hTgs1 to amino acid 662 (thereby penetrating the conserved region) abolished its methyltransferase activity. Most important was our exploitation of yeast synthetic lethality to develop a genetic complementation assay for hTgs1 function in vivo. We thereby established the following: (i) the minimal C-terminal catalytic domain sufficed for the biological activity of hTgs1, and (ii) biological activity of hTgs1 in yeast was directly reflective of its TMG synthetic capacity. From these results, we surmise that the large N-terminal domain of hTgs1 is not strictly necessary for TMG capping in vivo. It remains be seen whether and how the N-terminal domain might contribute to hTgs1 function in the mammalian cells, which could embrace transactions other than TMG synthesis (27, 28). The hTgs1 N-terminal domain might exert effects on the intracellular localization, protein-protein interactions, or protein-nucleic acid interactions of hTgs1.

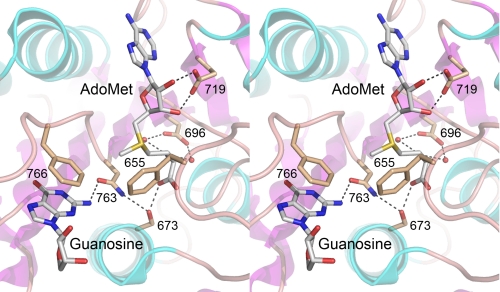

An alanine scan of 10 conserved residues of the hTgs1 catalytic domain identified seven (Phe-655, Asp-696, Asn-704, Asp-719, Asn-731, Trp-766, and Arg-807) as essential for methyltransferase activity in vitro and in vivo. Ala mutations at three other positions (Thr-673, Ser-763, and Asn-808) reduced hTgs1 activity in vitro and in vivo. The essential hTgs1 residues Asp-696, Asn-704, and Asp-719 are located within conserved peptide motifs that include the AdoMet-binding site; Ser-763 and Trp-766 are located within a conserved peptide that is proposed to include the binding site for the m7G methyl acceptor (13, 15, 16, 29). A fuller understanding of the basis for Tgs1 catalysis and substrate specificity awaits a crystal structure, either of the Michaelis complex or of binary complexes of Tgs1 with the methyl donor and acceptor. Meanwhile, we can interpret some of the mutational effects on hTgs1 in light of the recently reported crystal structure of the Thermus thermophilus 16 S rRNA guanine-N2 methyltransferase RsmC in complex with AdoMet and guanosine (76). A view of the RsmC active site (Fig. 11) shows that the guanosine N-2 atom is pointed toward the AdoMet methyl group, consistent with an in-line mechanism. Four of the amino acids identified here as essential for hTgs1 activity have easily identified counterparts in RsmC, whereby hTgs1 residues Phe-655, Asp-696, Asp-719, and Trp-766 correspond to RsmC residues Phe-207, Asp-239, Glu-262, and Phe-308, respectively. The residue numbers in Fig. 11 refer to the hTgs1 equivalents of the RsmC side chains shown. We surmise the following: (i) essential hTgs1 residue Asp-719 coordinates the ribose hydroxyls of AdoMet; (ii) essential residue Asp-696 makes water-mediated contacts to the AdoMet α-amino group; (iii) essential residue Trp-766 forms a π stack on the guanine base of the methyl acceptor (this would be a π-cation interaction with an m7G in the case of Tgs1); (iv) essential residue Phe-655 is poised over the reactive sulfonium of AdoMet. We speculate that the van der Waals contacts of Phe-655 to the AdoMet S-δ and C-ε atoms, and the electron-rich environment around the sulfonium, serve to stabilize the transition state of the transmethylation reaction.

FIGURE 11.

Insights to Tgs1 from the structure of rRNA guanine-N2 methyltransferase RsmC. Stereo view of the active site of T. thermophilus RsmC in complex with AdoMet and guanosine (from Protein Data Bank 3DMH). Highlighted are the RsmC side chains that contact the methyl donor and acceptor and that have putative counterparts in hTgs1. Hydrogen bond interactions are denoted by dashed lines. The residue numbers refer to the homologous positions in hTgs1.

Synthetic Genetic Interactions Suggest a Redundant Role of the TMG Cap in Spliceosome Assembly—It is a testament to the power of synthetic arraying that the output of the screen for mutational enhancement of tgs1Δ was highly biased toward proteins implicated in U1 and U2 snRNP function during pre-mRNA splicing. The two strongest interactors with Tgs1, resulting in synthetic lethality, were Mud2 and Nam8 (also known as Mud15). Mud2 and Nam8 were identified in a “MUD screen” (mutant U1 die) for yeast mutations that cause synthetic lethality with otherwise viable mutations in the U1 snRNA (30–32). Nam8 is an intrinsic RNA-binding component of the U1 snRNP and is present in the so-called commitment complex of U1 snRNP at the 5′ splice site, a key intermediate in spliceosome assembly (32, 33). Its putative mammalian homolog is the alternative-splicing regulator TIA-1 (34, 35). Although normally inessential for mitotic growth and splicing in yeast, Nam8 is necessary for splicing in situations when U1 snRNP binding to the splice site is inefficient (33, 36). Mud2, the yeast homolog of metazoan splicing factor U2AF65, interacts with the pre-mRNA/U1snRNP commitment complex in a manner that depends on the branch point sequence of the intron; Mud2 is proposed to facilitate subsequent recruitment of the U2 snRNP (31, 37). The synthetic lethal interactions of Nam8 and Mud2 with Tgs1 suggest a simple explanation for the surprising inessentiality of conserved components of the RNA “metabolome,” TMG caps, Nam8 and Mud2, whereby spliceosome assembly depends on either the TMG cap structure or Nam8 and Mud2, because the TMG cap on the U1 (or U2) snRNA is functionally redundant with certain proteins that assist U1 and/or U2 snRNP assembly on the pre-mRNA.

Synthetic interactions of Tgs1 with other splicing factors reinforce this model of functional redundancy of TMG caps. Brr1, which displays a strong synthetic sick interaction with Tgs1, is a 40-kDa snRNP-associated protein important for cell growth and splicing at cold growth temperatures (38). brr1 cells have decreased levels of U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs at 16 °C; the brr1 conditional growth defect can be reversed by overexpression of the core SmD1 component of the U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNPs (38). brr1 cells have a kinetic delay in 3′-processing of U2 snRNA at restrictive temperature (38). Synergy between Tgs1 and Brr1 suggests that TMG caps and Brr1 might play overlapping roles in U2 snRNP biogenesis and function.

Consistent with this idea, we documented synthetic interactions between Tgs1 and two U2-specific snRNP proteins, Lea1 and Ist3 (also known a Snu17), and between Tgs1 and the U1-specific Mud1 protein (Table 1). Lea1 is the homolog of the mammalian U2A′ protein (39). lea1Δ cells are temperature-sensitive (39; Fig. 1) and have reduced U2 snRNA levels (39). Extracts of lea1Δ cells display an in vitro defect in spliceosome assembly at the step of U2 snRNP addition to the commitment complex (39). Ist3 is a 17-kDa RNA-binding component of the U2 snRNP (40). The single ist3Δ mutation confers a temperature-sensitive growth phenotype in our strain background (Fig. 1) and synergizes strongly with tgs1Δ at 25 °C. Gottschalk et al. (40) found that ist3Δ cells have normal levels of U2 snRNPs. Yet, extracts of ist3Δ cells have feeble in vitro splicing activity and accumulate unusual U2 snRNP-containing intermediates in the spliceosome assembly process (40). Mud1 is an intrinsic component of the U1 snRNP and is a homolog of mammalian U1A (30, 47). Ablation of Mud1 has no apparent effect on splicing in vitro or in vivo when wild-type U1 RNA is present. However, Mud1 becomes important when yeast rely on a mutated U1 snRNA, leading to the suggestion that Mud1 helps maintain the U1 snRNP in an active conformation (30).

Three other known splicing factors displayed Tgs1 mutational enhancement: Isy1, Cwc21, and Bud13 (Table 1). Isy1 (also known as Ntc30) is a nonessential spliceosome protein (41) and a constituent of the “nineteen complex,” a multiprotein assembly that interacts with the essential splicing factor Prp19 (42, 43). Isy1 binds the spliceosome at the point during its assembly when the U4 snRNP is ejected (42). Ablation of Isy1 impacts the efficiency of the first catalytic step of splicing and the fidelity of the second step (44). Cwc21 and Bud13 (also known as Cwc26) are components of a multiprotein “Cef1 complex,” associated with Cef1, an essential splicing factor and a component of the nineteen complex (45). The Cef1 complex consists of the constituents of the nineteen complex plus many additional splicing factors (45), among which are Lea1, Ist3, and Cwc21, and Bud13 that we see are synthetic enhancers of tgs1Δ. Bud13 was independently identified as a component of the heterotrimeric RNA retention and splicing (RES) complex composed of Bud13, Ist3/Snu17, and Pml1 (46).

One of the strongest synthetic sick tgs1Δ interactions was with YNL187w (Fig. 2), an unchristened yeast open reading frame encoding a 357-aa polypeptide. YNL187w had been identified previously by Murphy et al. (51) in a screen for synthetic enhancement with an otherwise viable mutation of Prp40, an essential constituent of the U1 snRNP (47). The YNL187w protein was also scored as interacting with the core SmB1 protein in a two-hybrid screen (53), suggesting that it too could be a nonessential spliceosome protein. Its synergy with Tgs1 supports that idea; thus we propose that YNL187w be known henceforth as Swt21 (synthetic with Tgs1 number 21; see Table 1). To our inspection, the Swt21 protein belongs to the WD40 repeat family.

In sum, the physical association of so many of the splicing factors identified as Tgs1 synthetic enhancers with each other, with either individual snRNPs or larger snRNP complexes (48), or with early spliceosome assembly intermediates provides a compelling case for an important, albeit redundant, function of the TMG cap during splicing in mitotically growing yeast. A striking feature of the Tgs1 genetic “neighborhood” is its inclusion of three splicing factors, Nam8, Ist3, and Bud13, that are nonessential in mitotic cells, but essential during meiosis, by virtue of their requirement for Mer1-activated splicing of pre-mRNAs that encode proteins required for meiotic recombination and cell division (35, 49, 50). The pre-mRNAs subject to meiotic splicing regulation have either suboptimal 5′ splice sites or a large 5′ exon that apparently dictates their reliance on otherwise nonessential splicing factors. In this context, it is noteworthy that a genome-wide screen of the yeast single-gene deletion library for defects in sporulation and meiosis identified Tgs1 as a novel sporulation factor (52). A homozygous tgs1Δ diploid strain displayed low sporulation efficiency. Survey of meiotic landmarks indicated that induction of the early meiosis-specific transcription factor IME1 occurred in tgs1Δ diploids, but nuclear division did not occur (52).

Synthetic Genetic Interactions with Proteins Involved in RNA Decay—Strong synthetic sick tgs1Δ interactions were observed with the following three yeast proteins involved in RNA decay pathways: Lsm1, Pat1, and Trf4. Lsm1 and Pat1 are components of the RNA decapping machinery that exposes RNA 5′ ends to exonucleolytic digestion. Lsm1 is the distinctive subunit of a cytoplasmic heptameric Lsm1–7 complex that associates with Pat1 (an activator of decapping) and Xrn1 (a 5′-exoribonuclease) (54–56). These proteins, along with the Dcp1/2 decapping enzyme, localize to cytoplasmic P-bodies within which mRNAs are degraded (57). It is difficult to envision how a defect in cytoplasmic mRNA decapping and decay caused by ablation of Pat1 and Lsm1 function might synergize with the absence of trimethylguanosine caps on certain nuclear RNAs. It seems more plausible to invoke an additional role for Pat1 and Lsm1 in nuclear RNA transactions that involve TMG-capped RNAs. This hypothesis is in keeping with recent findings that a fraction of Pat1 is localized in the nucleus (57) and the identification of Pat1 and Lsm1 as components of the purified yeast spliceosomal penta-snRNP (48). We speculate that Pat1 and Lsm1 could play a role in spliceosome assembly that was previously unappreciated because of functional overlap with the TMG cap.

Trf4 (also known as Pap2) is a catalytic subunit of the TRAMP complex, a nuclear poly(A) polymerase that targets certain transcripts for decay by adding a 3′ poly(A) tail that serves as beacon for 3′-exonucleolytic degradation by the exosome (58–61). In light of evidence that the exosome is involved in forming the mature 3′ ends of U1, U4, and U5 snRNAs (62–64), we envision a scenario for synergy of Trf4 and Tgs1 in which snRNA maturation or function in the face of a 3′ end-formation defect becomes more acutely dependent on the TMG cap.

Genetic Links between Tgs1 and Transcription Regulators—We recovered six yeast transcriptional regulators as synthetic enhancers of tgs1Δ (Table 1). These proteins play key roles in assembly of the pol II initiation complex and/or chromatin dynamics. Srb2 and Soh1(Med31) are subunits of the RNA polymerase II mediator complex (65–67). Spt3 is a subunit of the SAGA complex (68). Rpn4 is a DNA-binding transcription factor that regulates expression of genes encoding proteasome subunits (69). Swr1 is an ATPase subunit of a chromatin remodeling factor that deposits the histone variant Htz1 (H2A.Z) at the 5′ end of yeast transcription units (70–73). Two plausible scenarios could explain how these proteins synergize with Tgs1 as follows: (i) an indirect effect whereby they regulate the expression of genes either involved in splicing or snRNP formation (e.g. there is an Rnp4-binding site located at the 5′ end of the yeast U2 snRNA gene) (74), or (ii) a direct effect whereby they aid in physically and temporally coupling pre-mRNA splicing to pol II transcription.

A Tgs1 Neighborhood—Gene-specific and genome-wide analyses of the functional and physical interactions of yeast gene products have provided powerful insights to cellular physiology. All of the available interactions (two-hybrid, affinity purification, synthetic enhancement, synthetic suppression, dosage suppression, dosage lethality, etc.) are curated at Saccharomyces Genome Data Base, where the cupboard containing Tgs1 is virtually bare. Tgs1 was identified originally in a two-hybrid screen against snRNP core protein SmB. Tgs1 binds in vitro to snRNP proteins SmB and SmD1 and to snoRNP proteins Nop58 and Cbf5 (12). As shown here and previously (14, 15), the guanine-N2 methyltransferase activity of Tgs family proteins does not require a specific RNA polynucleotide or a protein cofactor. Tgs1 has not been detected as a stable constituent of purified yeast spliceosomal snRNPs (32, 48). Accordingly, the interactions with snRNP core proteins are likely to be transient in vivo and serve the purpose of targeting guanine-N2 methylation to just a few of the cellular RNAs that contain an m7G cap. Tgs1 interactions with snoRNP proteins could be relevant to the imputed function of Tgs1 in nucleolar ribosome assembly at low growth temperatures at which tgs1Δ cells are inviable (75). Note that this particular function of S. cerevisiae Tgs1 is unrelated to its TMG synthase catalytic activity (75).

By identifying 21 yeast proteins that overlap functionally with Tgs1 in vivo, we gain an understanding of the likely role of the TMG cap in RNA metabolism, insofar as the largest group of interactors includes a coherent set of proteins involved in snRNP function and spliceosome assembly. Other interactors include pol II transcriptional regulators and RNA 3′-processing/decay factors. The full spectrum of genetic and physical interactions between the 21 Tgs1 synthetic enhancers (“in-group” interactions) have been culled from SGD and are listed in Table 1. As one might expect, many of the Tgs1-interaction splicing proteins interact with one another physically or functionally. The same is true of the transcriptional regulators. The remarkable aspect is that many of the Tgs1 interactors interact with each other across the functional categories. For example: (i) decay factors Pat1 and Lsm1 score as interactors with both transcription regulators and splicing factors, and (ii) splicing factors Ist3, Cwc21, Bud13, and Lea1 are annotated as interactors with various transcriptional regulators (Table 1). Our results suggest the existence of a dense local neighborhood (21, 23) surrounding Tgs1 that embraces RNA transactions in which the TMG cap overlaps the functions of the interacting proteins. Although dissecting the molecular basis of the synthetic phenotypes of the 21 Tgs1 interactions described here is well beyond the scope of this study, there is no shortage of testable hypotheses (see above). In addition to providing a useful genetic assay for TMG synthase activity in vivo, as documented here, the synthetic lethal and synthetic sick double mutants comprise a valuable toolkit for structure-function studies of some of the nonessential proteins listed in Table 1.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM52470 (to S. S. and B. S.). This work was also supported by Research Agreement 2004-OGI-3-01 from Genome Canada, the Ontario Genomics Institute, and Research Agreement GSP-41567 from Canadian Institutes of Health (to C. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AdoMet, S-adenosylmethionine; TMG, 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine; snRNP, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; aa, amino acid; BSA, bovine serum albumin; FOA, 5-fluoroorotic acid; AdoHcy, S-adenosylhomocysteine; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA; h, human; y, yeast.

References

- 1.Shuman, S. (2001) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 66 301-312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwer, B., and Shuman, S. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 4328-4332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fresco, L. D., and Buratowski, S. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 6624-6628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan, P., Piano, F., and Shatkin, A. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 14168-14173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takagi, T., Walker, A. K., Sawa, C., Diehn, F., Takase, Y., Blackwell, T. K., and Buratowski, S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 14174-14184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ping, Y. H., Chu, C., Cao, H., Jacque, J. M., Stevenson, M., and Rana, T. M. (2004) Retrovirology 1 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao, X., Schwer, B., and Shuman, S. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 475-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwer, B., Mao, X., and Shuman, S. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26 2050-2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch, H., Reddy, R., Rothblum, L., and Choi, Y. C. (1982) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 51 617-654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seto, A. G., Zaug, A. J., Sobel, S. G., Wolin, S. L., and Cech, T. R. (1999) Nature 401 177-180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liou, R. F., and Blumenthal, T. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 1764-1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouaikel, J., Verheggen, C., Bertrand, E., Tazi, J., and Bordonné, R. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 891-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouaikel, J., Bujnicki, J. M., Tazi, J., and Bordonné, R. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 4899-4909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausmann, S., and Shuman, S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 4021-4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hausmann, S., and Shuman, S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 32101-32106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausmann, S., Ramirez, A., Schneider, S., Schwer, B., and Shuman, S. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35 1411-1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verheggen, C., Lafontaine, D. L. J., Samarsky, D., Mouaikel, J., Blanchard, J. M., Bordonné, R., and Bertrand, E. (2002) EMBO J. 21 2736-2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemm, I., Girard, C., Kuhn, A. N., Watkins, N. J., Schneider, M., Bordonné, R., and Lührmann, R. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 3221-3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komonyi, O., Papai, G., Enunlu, I., Muratoglu, S., Pankotai, T., Kopitova, D., Maróy, P., Udvarty, A., and Boros, I. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 12397-12404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong, A. H., Evangelista, M., Parsons, A. B., Xu, H., Bader, G. D., Page, N., Robinson, M., Raghibizadeh, S., Hogue, C. W., Bussey, H., Andrews, B., Tyers, M., and Boone, C. (2001) Science 294 2364-2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong, A. H., Lesage, G., Bader, G. D., Ding, H., Xu, H., Xin, X., Young, J., Berriz, G. F., Brost, R. L., Chang, M., Cheng, X., Chua, G., Friesen, H., Goldberg, D. S., Haynes, J., et al. (2004) Science 303 808-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong, A. H., and Boone, C. (2006) Methods Mol. Biol. 313 171-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boone, C., Bussey, H., and Andrews, B. J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Genet. 8 437-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein, A. L., and McCusker, J. H. (1999) Yeast 15 1541-1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiestl, R. H., and Gietz, R. D. (1989) Curr. Genet. 16 339-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girard, C., Verheggen, C., Neel, H., Cammas, A., Vagner, S., Soret, J., Bertrand, E., and Bondonné, R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 2060-02069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu, Y., Qi, C., Cao, W. Q., Yeldandi, A. V., Rao, M. S., and Reddy, J. K. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 10380-10385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra, P., Qi, C., Yu, S., Shah, S. H., Cao, W. Q., Rao, M. S., Thimmapaya, B., Zhu, Y., and Reddy, J. K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 20011-20019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabrega, C., Hausmann, S., Shen, V., Shuman, S., and Lima, C. D. (2004) Mol. Cell 13 77-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao, X. C., Tang, J., and Rosbash, M. (1993) Genes Dev. 7 419-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abovich, N., Liao, X. C., and Rosbash, M. (1994) Genes Dev. 8 843-854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gottschalk, A., Tang, J., Puig, O., Salgado, J., Neubauer, G., Colot, H. V., Mann, M., Séraphin, B., Rosbash, M., Lührmann, R., and Fabrizio, P. (1998) RNA (N. Y.) 4 374-393 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puig, O., Gottschalk, A., Fabrizio, P., and Séraphin, B. (1999) Genes Dev. 13 569-580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Gatto-Konczak, F., Bourgeois, C. F., Le Guiner, C., Kister, L., Gesnel, M., Stévenin, J., and Breathnach, R. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 6287-6299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Förch, P., Puig, O., Kedersha, N., Martinez, C., Granneman, S., Séraphin, B., Anderson, P., and Valcárcel, J. (2000) Mol. Cell 6 1089-1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spingola, M., and Ares, M. (2000) Mol. Cell 6 329-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutz, B., and Seraphin, B. (1999) RNA (N. Y.) 5 819-831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noble, S. M., and Guthrie, C. (1996) EMBO J. 15 4368-4379 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caspary, F., and Séraphin, B. (1998) EMBO J. 21 6348-6358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottschalk, A., Bartels, C., Neubauer, G., Lührmann, R., and Fabrizio, P. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3037-3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dix, I., Russell, C., Ben Yehuda, S., Kupiec, M., and Beggs, J. D. (1999) RNA (N. Y.) 5 360-368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, C. H., Tsai, W. Y., Chen, H. R., Wang, C. H., and Cheng, S. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 488-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, C. H., Yu, W. C., Tsao, T. Y., Chen, H. R., Lin, J. Y., Tsai, W. Y., and Cheng, S. C. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 15 1029-1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villa, T., and Guthrie, C. (2005) Genes Dev. 19 1894-1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohi, M. D., Link, A. J., Ren, L., Jennings, J. L., McDonald, W. H., and Gould, K. L. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 2011-2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dziembowski, A., Ventura, A. P., Rutz, B., Caspary, F., Faux, C., Halgand, F., Leprévote, O., and Séraphin, B. (2004) EMBO J. 23 4847-4856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neubauer, G., Gottschalk, A., Fabrizio, P., Séraphin, B., Lührmann, R., and Mann, M. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 385-390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens, S. W., Ryan, D. E., Ge, H. Y., Moore, R. E., Young, M. K., Lee, T. D., and Abelson, J. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 31-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spingola, M., Armisen, J., and Ares, M. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1242-1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scherrer, F. W., and Spingola, M. (2006) RNA (N. Y.) 12 1361-1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy, M. W., Olson, B. L., and Siliciano, P. G. (2004) Genetics 166 53-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enyenihi, A. H., and Saunders, W. S. (2003) Genetics 163 47-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fromont-Racine, M., Rain, J. C., and Legrain, P. (1997) Nat. Genet. 16 277-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouveret, E., Rigaut, G., Schevchenko, A., Wilm, M., and Séraphin, B. (2000) EMBO J. 19 1661-1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tharun, S., He, W., Mayes, A. E., Lennertz, P., Beggs, J. D., and Parker, R. (2000) Nature 404 515-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pilkington, G. R., and Parker, R. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 1298-1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teixeira, D., and Parker, R. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 2274-2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kadaba, S., Krueger, A., Trice, T., Krecic, A. M., Hinnebusch, A. G., and Anderson, J. (2004) Genes Dev. 18 1227-1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LaCava, J., Houseley, J., Saveanu, C., Petfalski, E., Thompson, E., Jaquier, A., and Tollervey, D. (2005) Cell 121 713-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyers, F., Rougemaille, M., Badis, G., Rouselle, J. C., Dufour, M. E., Boulay, J., Régnault, B., Devaux, F., Namane, A., Séraphin, B., Libri, D., and Jacquier, A. (2005) Cell 121 725-737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanacova, S., Wolf, J., Martin, G., Blank, D., Dettwiler, S., Friedlin, A., Langen, H., Keith, G., and Keller, W. (2005) PLoS Biol. 3 986-997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allmang, C., Kufel, J., Chanfreau, G., Mitchell, P., Petfalski, E., and Tollervey, D. (1999) EMBO J. 18 5399-5410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Hoof, A., Lennertz, P., and Parker, R. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 441-452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell, P., Petfalski, E., Houalla, R., Podtelejnikov, A., Mann, M., and Tollervey, D. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 6982-6992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson, C. M., Koleske, A. J., Chao, D. M., and Young, R. A. (1993) Cell 73 1361-1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Linder, T., and Gustafsson, C. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 49455-49459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giglielmi, B., van Berkum, N. L., Klapholz, B., Bijma, T., Boube, M., Boschiero, C., Bourbon, H. M., Holstege, F. C. P., and Werner, M. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32 5379-5391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu, P. J., Ruhlmann, C., Winston, F., and Schultz, P. (2004) Mol. Cell 15 199-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dohmen, R. J., Willers, I., and Marques, A. J. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773 1599-1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krogan, N. J., Keogh, M. C., Datta, N., Cawa, C., Ryan, O. W., Ding, H., Haw, R. A., Pootoolal, J., Tong, A., Canadien, V., Richards, D. P., Wu, X., Emili, A., Hughes, T. R., Buratowski, S., and Greenblatt, J. F. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 1565-1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mizuguchi, G., Shen, X., Landry, J., Wu, W. H., Sen, S., and Wu, C. (2004) Science 303 343-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobor, M. S., Vankatasubrahmanyan, S., Meneghini, Gin, J. W., Jennings, J. L., Link, A. J., Madhani, H. D., and Rine, J. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2 587-599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guillemette, B., and Gaudreau, L. (2006) Biochem. Cell. Biol. 84 528-535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harbison, C. T., Gordon, D. B., Lee, T. I., Rinaldi, N. J., McIsaac, K. D., Danford, T. W., Hannett, N. M., Tagne, J. B., Reynolds, D. B., Yoo, J., Jennings, E. G., Zeitlinger, J., Pokholok, D. K., Kellis, M., Rolfe, P. A., Takusagawa, K. T., Lander, E. S., Gifford, D. K., Traenkel, E., and Young, R. A. (2004) Nature 431 99-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colau, G., Thiry, M., Leduc, V., Bordonné, R., and Lafontaine, D. L. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 7976-7986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Demirci, H., Gregory, S. T., Dahlberg, A. E., and Jogl, G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 26548-26556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]