Abstract

Human brains retain discrete populations of micro RNA (miRNA) species that support homeostatic brain gene expression functions; however, specific miRNA abundance is significantly altered in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer disease (AD) when compared with age-matched controls. Here we provide evidence in AD brains of a specific up-regulation of an NF-κB-sensitive miRNA-146a highly complementary to the 3′-untranslated region of complement factor H (CFH), an important repressor of the inflammatory response of the brain. Up-regulation of miRNA-146a coupled to down-regulation of CFH was observed in AD brain and in interleukin-1β, Aβ42, and/or oxidatively stressed human neural (HN) cells in primary culture. Transfection of HN cells using an NF-κB-containing pre-miRNA-146a promoter-luciferase reporter construct in stressed HN cells showed significant up-regulation of luciferase activity that paralleled decreases in CFH gene expression. Treatment of stressed HN cells with the NF-κB inhibitor pyrollidine dithiocarbamate or the resveratrol analog CAY10512 abrogated this response. Incubation of an antisense oligonucleotide to miRNA-146a (anti-miRNA-146a; AM-146a) was found to restore CFH expression levels. These data indicate that NF-κB-sensitive miRNA-146a-mediated modulation of CFH gene expression may in part regulate an inflammatory response in AD brain and in stressed HN cell models of AD and illustrate the potential for anti-miRNAs as an effective therapeutic strategy against pathogenic inflammatory signaling.

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is a common, age-related neurodegenerative disorder characterized clinically by the progressive erosion of cognition and memory and neuropathologically by defective gene expression and an up-regulation of inflammatory signaling (1–6). DNA array, Northern, reverse transcription-PCR, and Western analysis of AD neocortex and hippocampus have repeatedly shown a significant disruption in the homeostatic expression of essential brain genes, and abundant data continue to support the hypothesis that progressive up-regulation of inflammatory gene expression, driven in part by overactivation of transcription factor NF-κB, underlies elevated inflammatory signaling that supports the development and progression of the AD process (6–17). Micro RNAs (miRNAs), ∼22-nucleotide RNA molecules that represent a family of heterogeneous, evolutionarily conserved, regulatory RNAs that recognize the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of specific messenger RNA (mRNA) targets, regulate the post-transcriptional stability or translational efficiency of target mRNAs to function as natural negative regulators of gene expression (18–20). Of the 834 human miRNAs so far identified, only a specific subset are highly expressed in the brain, and these miRNAs appear to be critical to the regulation of normal brain cell function. Although miRNAs are known to be dynamically regulated during neural development, differentiation, and aging (11–18), the roles of miRNAs in inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases such as AD are not well understood. Very recent studies show that of the total miRNA population expressed in the healthy aging brain, only a selective subset appear to be involved in the AD process and that altered miRNA-mediated processing of mRNA populations may contribute to atypical mRNA abundance, altered gene expression, pro-inflammatory signaling, and secretase-mediated neurodegenerative aspects of AD pathology (20–26).

Because few miRNAs have been functionally linked to specific neurochemical pathways, these studies were undertaken to further understand the involvement of specific brain-enriched miRNAs in the molecular-genetic mechanism that drives inflammatory signaling and AD-type change. How certain mRNA populations, encoded by neural-essential genes, are significantly reduced in light of global elevations of the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB may be explained in part through the negative regulatory actions of specific miRNA species. This study provides evidence that up-regulation of an NF-κB-regulated brain-enriched miRNA-146a down-regulates a specific mRNA target encoding complement factor H (CFH), a repressor protein known to contribute to the regulation of the immune and inflammatory response of the brain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Human Brain Tissues—Human brain tissues were obtained from the Oregon Health Sciences Center (Portland OR), the University of California (Irvine, CA), and our own brain bank at the Louisiana State University Neuroscience Center (New Orleans LA); archived RNA samples were also obtained from the University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada). Brain tissues were used in accordance with the institutional review board/ethical guidelines at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center and donor institutions (6, 14, 15). Table 1 summarizes the selection of control and AD hippocampal and superior temporal lobe neocortical tissues employed in this study. All of the hippocampal and neocortical tissue samples were male or female Caucasian, because the post-mortem interval (PMI, which indicates the death to brain-freezing interval) is a factor that can affect RNA quality (6, 13–15); all of the RNAs were derived from tissues having a PMI of 4.2 h or less. Center to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease/National Institutes of Health criteria were used to categorize AD tissues in accordance with established guidelines; all of the AD tissues used in these studies had a clinical dementia rating of two or three, indicating the moderate- to severe stage of this neurological disorder (13–15).

TABLE 1.

Summary of tissues used from each case group in this study

The age is the time of death; age range refers to ranges of the individual means; and PMI (death to brain freezing interval) is the mean in hours. RNA A260/280 and RNA 18 S/28 S ratios are indicative of high brain tissue RNA spectral quality (14, 20, 22). There was no significant difference between control or Alzheimer total RNA yield. Characterization of control and Alzheimer total RNA message is shown. Hippocampal and temporal lobe neocortical tissue samples were male or female Caucasian. The means are the averages of n = 23 for each case group.

| Case group | Age | Age range | PMI*2 rangea | RNA A260/280 | RNA 28 S/18 S | RNA yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| years | years | |||||

| Control | 70.7 ± 8.1 | 65-76 | 1.1-4.2 | 2.05-2.13 | 1.4-1.6 | 1.1-1.4 |

| Alzheimer | 72.2 ± 6.6 | 67-78 | 1.2-4.1 | 2.08-2.10 | 1.4-1.5 | 1.05-1.5 |

Death to brain freezing interval in hours at -81 °C.

The values are the average yield in total μg RNA/mg of wet weight of brain tissue.

HN Cells in Primary Culture—HN cells (CC-2599; Lonza Biosciences-Cambrex, Walkersville, MD), a co-culture of human neuronal and glial cells, were grown in human neural maintenance medium (HNMM) supplemented with human fibroblast growth factor, neuronal survival factor 1 epidermal growth factor, and gentamicin-amphotericin B G/A as previously described (11, 15, 22, 26). HNMM was changed at 3.5 -day intervals; after 2 weeks of culture, the cytokine-stressed HN cell group received at each HNMM change human recombinant IL-1β (I4019; Sigma-Aldrich), AB42 peptide, H2O2, and/or human serum albumin as a control (11, 26) and were cultured for one additional week, after which the total RNA and protein fractions were prepared (22, 26).

HN Cell Transfection—Two-week-old HN cells were transfected with an NF-κB-containing pre-miRNA-146a promoter and luciferase reporter vector (50 nm; A547; Addgene, Cambridge, MA) or a Renilla control vector (Promega) using FuGENE 6 following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). At 24–48 h post-transfection, under various treatment conditions, the cells were processed for luciferase assay using a luciferase reporter assay kit (Dual Luciferase System; Promega) (11, 26). miRNA Isolation from Human Tissues and Cells—In human tissue studies 10-mg wet weight samples were isolated from the hippocampal CA1 region or the superior temporal lobe neocortex of AD brain or age-matched controls. In HN cell studies cells from three to six 70% confluent 3.5-cm diameter 6-well CoStar plates were scraped, taken up into a 20-ml syringe and RNase- and DNase-free, diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated plasticware, and gently packed using centrifugation (11, 26). For both tissues and cells, a guanidine isothiocyanate- and silica gelbased membrane total RNA purification system was used to isolate total RNA (5SRNA, tRNA, miRNA, and mRNA) from each sample. A miRNA isolation kit (PureLink™; Invitrogen) was further used to isolate miRNA from total RNA samples. Total RNA concentrations were quantified using RNA 6000 Nano LabChips and a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Caliper Technologies, Mountainview, CA; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) and typically yielded about 1. 6–1.9 μg of total RNA/mg of wet weight of tissue. No significant differences between the spectral purity or molecular size of small RNA between AD and control tissue samples were noted (see Table 1). Total small RNA was typically run out on 15% Tris-Borate-EDTA-urea polyacrylamide denaturing gels (TBE-urea; Invitrogen), and after ethidium bromide staining the total miRNA species (<25 nucleotides) were excised and end-labeled using [γ-32P]δATP (6000 Ci/mmol) according to the manufacturer's protocols (Invitrogen) (20, 26).

DNA Arrays and Brain-enriched miRNAs—As a preliminary screen and to obtain general trends for miRNA abundance, total miRNA was pooled and analyzed as an AD group (n = 23) and an age-matched control group (n = 23) using commercially available miRNA arrays (LC Sciences, Houston, TX). Specific controls and miRNAs showing strong hybridization signals in disease or controls were studied further. Subsequently, DNA targets for human 5SRNA, miRNA-9, miRNA-132, and miRNA-146a (see Table 2) were spotted onto GeneScreen Plus nylon membranes using a Biomek® 2000 laboratory automation work station (Beckmann, Fullerton, CA), and these mini-miRNA array panels were cross-linked, baked, hybridized, and probed according to the manufacturer's protocol (PerKinElmer Life Sciences Research Products, Boston, MA) (20, 26). Every second mini-miRNA array panel generated was normalized by probing with purified single radiolabeled miRNAs (5SRNA, miRNA-9, miRNA132, and/or miRNA-146a) to ascertain equivalent 5SRNA and individual miRNA loadings (26). Mini-miRNA panels were next probed with total labeled miRNAs isolated from late adult AD or control hippocampus or neocortex. AD or control extracts (25 μg) containing miRNA or 5SRNA (5 μg) were run out on 15% TBE-urea denaturing gels, transferred to GeneScreen membranes, cross-linked, baked, hybridized, and probed with specific DNA oligomers corresponding to specific miRNAs (see Table 2), radiolabeled using [γ-32P]δATP (6000 Ci/mmol) and a T4 polynucleotide kinase labeling system (Invitrogen) (14, 15, 20, 26).

TABLE 2.

DNA sequences of miRNA and anti-miRNA-146a (AM-146A) probes used in this study

The 5SRNA probe was derived from the first 21 nucleotides of the 107-nucleotide human 5SRNA (20, 26). AM-146a control (AM-146ac), containing the same nucleotide composition as anti-miRNA-146a, is a scrambled anti-miRNA-146a control oligonucleotide.

| RNA species | GenBank™ accession number or designation | DNA sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 5SRNA | NR002758 | 5′-ATACTCTGGTTTCTCTTCAGA-3′ |

| miRNA-9 | AJ459704 | 5′-TCTTTGGTTATCTAGCTGTATGA-3′ |

| miRNA-132 | AJ459743 | 5′-TAACAGTCTACAGCCATGGTCGT-3′ |

| miRNA-146a | EU147785 | 5′-TGAGAACTGAATTCCATGGGTT-3′ |

| Anti-miRNA-146a | AM-146a | 5′-AACCCATGGAATTCAGTTCTCA-3′ |

| AM-146a control | AM-146ac | 5′-CACATACAAGGGACTTTCTACT-3′ |

Gel Shift Assay—Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for NF-κB, oligonucleotide radiolabeling, normalization, and quantification using transcription factor SP1 as an internal control were performed as previously described (11, 13).

Anti-miRNA, Pyrollidine Dithiocarbamate (PDTC), or CAY10512 Treatments—A 22-oligonucleotide anti-miRNA-146a (AM-146a; 5′-AACCCATGGAATTCAGTTCTCA-3′) was used, at 5 and 20 nm concentrations, in 2-week-old HN cells at every 3.5 days, i.e. at every change of HNMM (see above; Lonza Biosciences-Cambrex) for a total treatment time of 1 week after IL-1β,Aβ42 peptide, and/or H2O2 induction. When required, 2-week-old HN cells were treated with the metal chelator, anti-oxidant, and NF-κB translocation inhibitor PDTC (P8765; Sigma) at 20 or 50 μm of PDTC or the polyphenolic trans-stilbene resveratrol analog CAY10512 (10009536; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) at 0.2 or 0.5 μm just prior to the addition of the NF-κB-containing pre-miRNA-146a promoter and luciferase reporter vector A547 (Figs. 3 and 6).

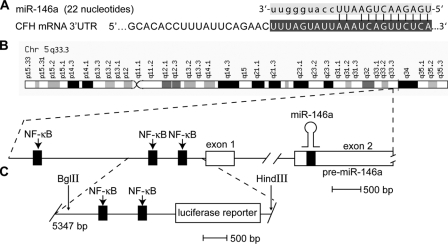

FIGURE 3.

The primary transcript for miRNA-146a (chr 5q33.3) is a NF-κB-regulated gene. A, the sequence of the 22-nucleotide miR-146a shows highly specific complementarity to the human CFH mRNA 3′-UTR (11 of 12 base pairs of the 5′ of miRNA-146a align; structural stability –27 kcal/mol) (21). B, chromosomal organization of the miRNA-146a gene locus on chromosome 5q33.3 indicating three NF-κB-DNA-binding sites in the pre-miRNA-146a gene promoter. C, BglII-HindIII fragment (5347 bp) of containing 547 bp of the proximal pre-miRNA-146a promoter containing two tandem NF-κB-binding sites linked to a luciferase reporter, used in the A547 construct (21, 30).

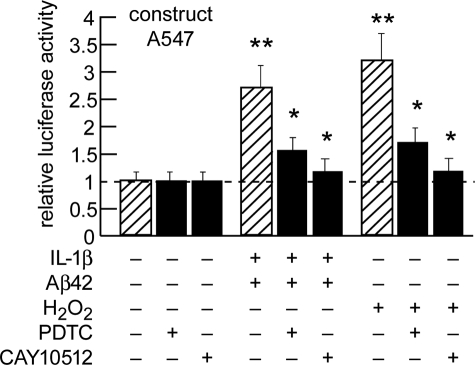

FIGURE 6.

Transfection of pre-miRNA-146a promoter-luciferase reporter pGL3 expression A547 construct into HN cells and inhibition with the NF-κB inhibitor PDTC or the resveratrol analog CAY10512. Two-week-old HN cells were transfected with an NF-κB-containing pre-miRNA-146a promoter and luciferase reporter vector (construct A547; Addgene, Cambridge, MA) using FuGENE 6 following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). The cells were untreated or treated with PDTC (20 μm) or CAY10512 (0.5 μm) just prior to IL-1β+Aβ42- or H2O2-induced stress (22, 26), and 24–48 h post-transfection, the cells were processed using a luciferase reporter assay kit (Dual Luciferase System; Promega). The significance over control was p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**) (ANOVA).

Data Analysis and Interpretation—5SRNA, an abundant 107 ribonucleotide marker, and miRNA-9 and miRNA-132, two human brain-enriched small RNAs, were used as internal controls for miRNA determinations in each brain sample. Relative miRNA and CFH mRNA signal strengths were quantified against 5SRNA in each sample using data acquisition software provided with a GS250 molecular imager (Bio-Rad). Graphic presentations were performed using Excel algorithms (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Statistical significance (p) was analyzed using a two-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A p < 0.05 was deemed as statistically significant; the experimental values in the figures are expressed as the means ± S.E.

RESULTS

Human Brain Case Selection and Messenger RNA Quality—Table 1 shows the age, age range, PMI in hours, RNA A260/280, RNA 28 S/18 S ratios, and RNA yields of adult control (n = 23) and Alzheimer (n = 23) brain tissues, many of which were previously analyzed for global miRNA and mRNA gene expression patterns (6, 10, 14, 15, 20, 26). PMIs for age-matched control or AD human brain tissues were all ≤4.2 h; sample tissues age-matched control or AD exhibited no significant differences in age (70.7 ± 5.1 versus 72.2 ± 6.1 years, p < 0.87), post-mortem interval (mean 2.6 ± 1.1 versus 2.5 ± 1.4 h, p < 0.96), or RNA A260/280 indices (2.1 ± 0.3 versus 2.09 ± 0.3, p < 0.97), age-matched control versus AD, respectively. We noted no differences in total RNA yields between the control and AD groups, although there was a trend in younger aged brains for a slightly higher total RNA yield (6, 14).

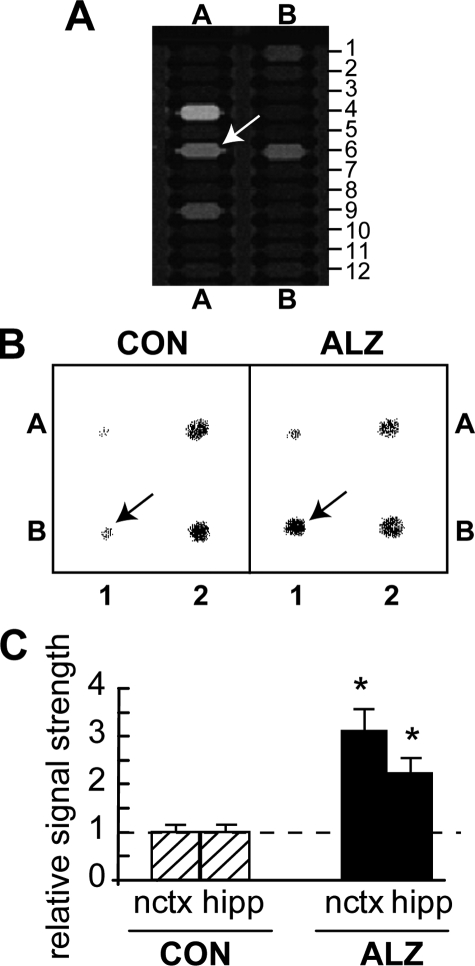

Relative Abundance of miRNA in Control and AD Brain—DNA miRNA arrays were initially used to screen for relative miRNA abundance in adult control neocortex and hippocampus, and then quantitative differences between adult control and AD miRNA in these 2 brain regions were further examined (20, 26) (Fig. 1A). DNA oligonucleotides corresponding to miRNAs of interest were then dot blotted and probed against total small RNA using mini-miRNA dot blot panels (20, 26) (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). Both DNA array-based analysis and the more quantitative Northern dot blot analysis showed that miRNA relative abundance in control brain was 5SRNA > miRNA-132 > miRNA-146a > miRNA-9 in adult neocortex and hippocampus changing to 5SRNA > miRNA-146a > miRNA-132 > miRNA-9 in AD brain tissue samples. Although abundant in the brain, 5SRNA, miRNA-9, and miRNA-132 exhibited no significant change in relative abundance among any of the samples tested.

FIGURE 1.

miRNA-146a up-regulation in AD brain. A, merge of cy3/cy5 signals from a human micro-RNA panel (LC Sciences) indicates specific up-regulation of miRNA-146a (position A6; arrow). Levels of miRNA-9 (position A4), miRNA-132 (position A9), or miRNA-185 (position B6) showed no such changes (complete miRNA grid pattern available from LC Sciences). B, nylon membrane-bound DNA equivalents (10 μm) of three brain-enriched miRNAs and 5SRNA were probed with total 32P-radiolabeled miRNA fractions isolated from control or AD affected hippocampal CA1; representative Northern hybridization of select brain-enriched miRNAs reconfirmed up-regulation of miR-146a (arrows). Position A1, miRNA-9; A2, miRNA-132; B1, miRNA-146a; B2, 5SRNA. C, signals were quantified against internal 5SRNA levels in bar graph format. Data analysis of 23 control (CON) and 23 Alzheimer (ALZ) brains show a 3.3-fold increase of miRNA-146a expression in the neocortex (nctx) and a 2.3-fold increase in the hippocampus (hipp) over age-matched controls. *, significance over control p < 0.01 (ANOVA).

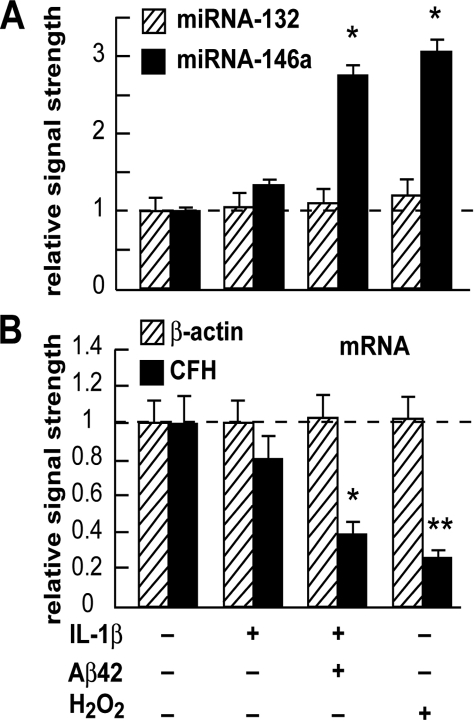

Relative Abundance of miRNA in Control and in IL-1β-, Aβ42-, and/or H2O2-stressed HN Cells—IL-1β- and Aβ42-stressed HN cells in primary culture have been used to study mechanistic aspects of inflammatory gene expression and signaling in in vitro models of AD, neurodegeneration, chelation, and metal-induced neurotoxicity studies (10, 11, 15, 22, 26, 29). HN cells treated with IL-1β alone showed a 1.35-fold increase in miRNA-146a abundance and no change in miRNA-132 abundance in the same sample when compared with untreated control HN cells (Fig. 2). When compared with untreated HN controls miRNA-146a showed a significant 2.7-fold increase in abundance after [IL-1β+Aβ42]-treatment and a 3.1-fold increase after treatment with H202. Under the same treatment conditions, no increases in the abundance of miRNA-132 (or 5SRNA or miRNA-9) were observed.

FIGURE 2.

Specific up-regulation of miRNA-146a, but not miRNA-132 in IL-1β, IL-1β+Aβ42, and in H2O2 treated HN cells in primary culture. A, 2-week-old HN cells were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml cell medium), IL-1β+Aβ42 (8 μm) (22), and/or H2O2 (2.5 μm) in HN maintenance medium for 1 week, representing, respectively, inflammatory cytokine IL-1β-, Aβ42 peptide-, and/or ROS-mediated stress for one-third of their in vitro lifetime. Total small RNA was isolated, radiolabeled, and used to probe dot blot arrays containing brain-enriched miRNA targets as previously described (20, 26). The results indicate a specific up-regulation of miRNA-146a but not a related brain-enriched miRNA-132, after IL-1β, IL-1β+Aβ42, or H2O2 treatment, to 1.4-, 2.6-, and 3.1-fold, respectively, over untreated normally aging HN cell controls. Control miRNA levels (miR-132 and miR-146a) arbitrarily set to 1.0 (dashed horizontal line; n = 4). *, p < 0.05 (ANOVA). B, down-regulation of CFH mRNA in the same HN cell samples as in A. Taken together with the data shown (A), the results suggest that miRNA-146a is up-regulated in HN cells stressed with inflammatory cytokines and amyloid peptides or oxidative stressors known to be present in AD brain (2–6, 14, 26).

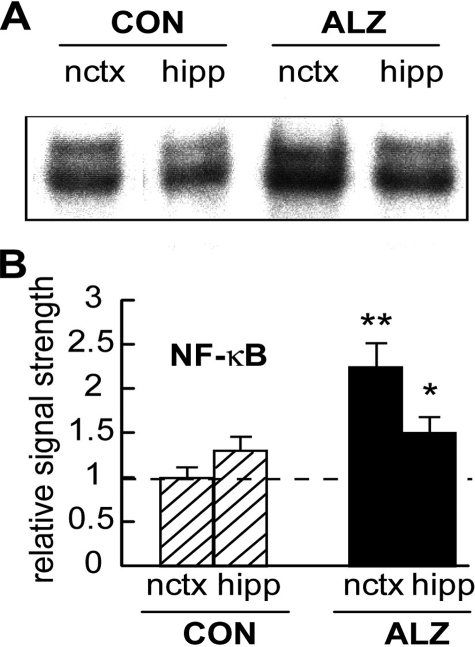

miRNA-146a Is Transcribed from a Pre-miRNA-146a NF-κB-regulated Gene—miRNA-146a is transcribed from a pre-miRNA-146a precursor gene, and the 5′ regulatory region of that gene has been sequenced revealing three upstream NF-κB-DNA binding sites (NT_023133; 21,26) (Fig. 3). Because of 1) endotoxin responsiveness, 2) activation by pro-inflammatory cytokines, 3) a proposed role for miRNA-146 in control of Toll-like receptor and cytokine signaling (21), 4) 5′ regulatory region promoter mapping studies, pre-miRNA-146a transcription and hence miRNA-146a abundance are thought to be under the regulatory control of NF-κB-DNA binding (21, 29). Using gel shift assay, we next assayed for NF-κB abundance in control and AD neocortex and hippocampus and found that in controls, NF-κB abundance was about 1.4-fold higher in the hippocampus when compared with the neocortex. However, in AD, the mean NF-κB signal was found to be 2.2-fold more abundant than in control neocortex and 1.2-fold more abundant than in control hippocampus (Fig. 4). This and previous data in cultured HN cells suggest that part of the inflammatory signaling pathway in IL-1β,Aβ42 peptide, and H2O2 oxidatively stressed and inflammation-triggered brain cells both in vitro and in vivo involves an up-regulation of the transcription factor NF-κB, which appears to be a transcription factor in part responsible for driving expression of the pre-miRNA-146 gene (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 4.

NF-κB is up-regulated in AD neocortex. A, NF-κB, a known inducer of pre-miR-146a transcription (Fig. 3) is up-regulated in AD affected neocortex and hippocampus compared with age-matched controls (13). Parallel electrophoretic mobility shift assay experiments for the transcription factor SP1 in control and AD brain and in stressed HN cells showed no such up-regulation and served as an internal experimental control (data not shown and Refs. 11, 13). B, data in bar graph format for control (CON) and Alzheimer (ALZ) neocortex (nctx) and hippocampus (hipp) indicate 2.2- and 1.2-fold increases in NF-κB-DNA binding, respectively (see text; n = 18 for each case group; Table 1). The significance when compared with controls was p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**) (ANOVA).

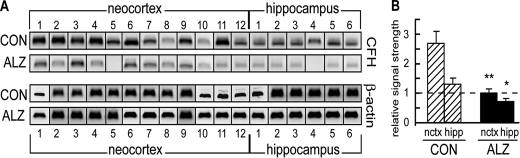

CFH Is Down-regulated in AD Brain—One strong predicted mRNA target for miRNA-146a is the CFH mRNA 3′-UTR (Fig. 3). Using the same whole tissue extracts as we analyzed in the previous section, we next analyzed for CFH protein abundance against β-actin protein abundance in 18 samples derived from control and AD neocortex and hippocampus (Fig. 5). CFH was found to be down-regulated in AD to 0.4-fold in the neocortex and 0.6-fold in the hippocampus, and the results were highly significant.

FIGURE 5.

CFH is down-regulated in AD brain. A, analysis of CFH, a highly specific miRNA-146a target and inflammatory regulator, in 18 Alzheimer (ALZ) and 18 control (CON) neocortical and hippocampal samples, compared with the control β-actin marker in the same tissue sample, shows a general down-regulation of CFH in ALZ neocortex and hippocampus compared with age-matched controls. The data analysis of 18 CON and 18 ALZ brains show a 2.7-fold decrease of CFH expression in the neocortex and a 2-fold decrease in the hippocampus. The significance over control was p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**) (ANOVA).

Transfection of HN Cells with A547-Luciferase Reporter Vector and Induction of the Pre-miRNA-146a Promoter with IL-1β, Aβ42, and/or H2O2—Transfection of HN cells with the A547-luciferase reporter vector (Fig. 3) showed no significant effects on relative luciferase signal strength in controls (leftmost bars in Fig. 6 and data not shown); however, in the presence of IL-1β+Aβ42, A547-luciferase activity was stimulated 2.7- and 3.2-fold in the presence of H2O2, and the results were highly significant (Fig. 6). Although the NF-κB inhibitors PDTC and CAY10512 had no effect on A547-luciferase reporter vector in transfected controls (leftmost bars in Fig. 6; data not shown), PDTC reduced A547-luciferase activity from 2.7- to 1.5-fold after IL-1β+Aβ42 treatment and reduced A547-luciferase activity from 3.2- to 1.7-fold after H2O2 treatment. Similarly the resveratrol analog CAY10512 had no effect on A547-luciferase reporter vector transfected controls (leftmost bars in Fig. 6; data not shown); however, CA10512 reduced A547-luciferase activity from 2.7- to 1.2-fold after IL-1β+Aβ42 treatment and reduced A547-luciferase activity from 3.2- to 1.2-fold after H2O2 treatment. In agreement with other reports, these data suggest an NF-κB-mediated mechanism of pre-miRNA-146a transcriptional activation (21, 30).

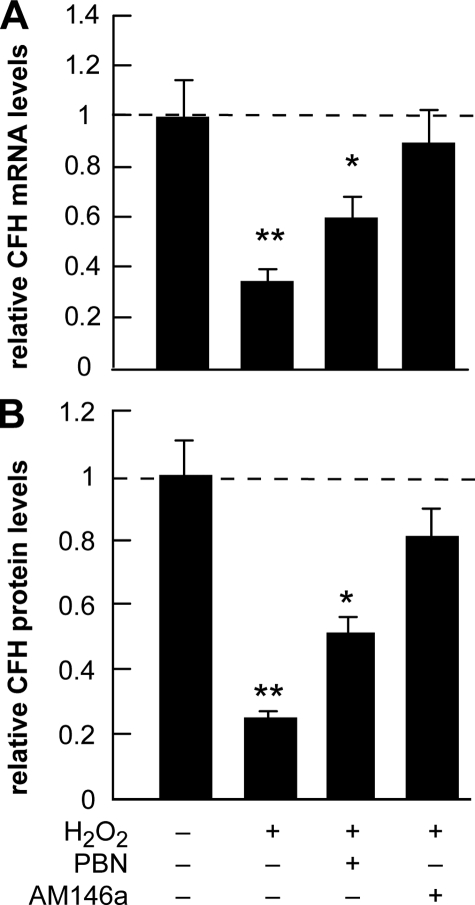

CFH Abundance in Stressed HN Cells and Treatment with Anti-miRNA-146a (AM-146a)—In these experiments the maximal amount of A547-luciferase reporter activity was found to be induced using the oxidative stress promoting H2O2, and this ROS-generating peroxide was subsequently used to study specific oxidative and miRNA effects on CFH expression in HN cells (Figs. 6 and 7). The presence of H2O2 alone was found to reduce CFH mRNA to 0.35-fold that of control and CFH protein abundance to 0.2-fold that of control; however, in the presence of the free radical scavenger phenyl butyl nitrone (PBN), this reduction was not as severe and reduced CFH mRNA abundance to 0.6-fold of control and CFH protein abundance to 0.5-fold that of control (Fig. 7). Incubation of HN cells with anti-miRNA-146a (AM-146a) restored CFH mRNA levels to 0.9-fold that of control and CFH protein levels to 0.8-fold of control levels, suggesting that the sequestration of miRNA-146a by AM-146a and the reduced free miRNA-146a abundance effectively restores HN cells to more homeostatic levels of CFH. When used in place of AM-146a, the scrambled AM-146a control oligonucleotide AM-146ac (containing the same nucleotide composition but in a different nucleotide order) (Fig. 3 and Table 2) exhibited none of these effects (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Expression of CFH in H2O2-stressed HN cells before and after treatment with the antioxidant PBN and an anti-miR-146a oligonucleotide AM-146a. A, 2-week-old HN cells were analyzed for CFH mRNA abundance before (leftmost bar) and after H2O2 (2.5 μm) for 1 week, representing the presence ROS-mediated stress for one-third of their in vitro lifetime. After ROS treatment a significant reduction of CFH mRNA abundance to 0.34 of control levels was observed. Treatment with PBN (5 μm twice daily to the culture medium) or the presence of an antisense oligonucleotide to miR-146a (AM-146a; 5 nm;5′-UUUAGUAUUAAAUCAGUUCUCA-3′; Ambion, Houston, TX; added with every change of culture medium) restored CFH mRNA levels to 0.61 and 0.9 of control levels, respectively. B, CFH protein abundance in same samples as in A. After ROS treatment, a reduction of CFH protein abundance to 0.24 of control levels was observed. Treatment with PBN or the presence of AM-146a as in A restored CFH protein levels to 0.5 and 0.8 of control levels, respectively. Individually, PBN or AM-146a had no significant effect on either CFH mRNA or protein levels in unstressed HN cells (data not shown). The significance over untreated control for mRNA and protein (leftmost lane; arbitrarily set to 1.0; dashed horizontal line) was p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**) (ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

Gene expression is regulated by a rich variety of chromatin- and sequence-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional signals that control and coordinate gene product abundance, and this is achieved in part through mRNA speciation and complexity (12–17). The neurobiology of the relatively recently described miRNAs and their roles in brain function in health and disease are only beginning to be appreciated (18–26). Of the 834 human miRNAs so far identified, only a specific subset is detectable or enriched in brain cells (23–25). Although miRNAs are generally regarded as negative regulators of gene expression, multiple miRNAs may regulate the expression of a single mRNA, and conversely, one miRNA may have multiple mRNA targets and hence multiple effects on the expression of several related gene families (18–27). The in vivo half-lives of specific miRNAs have not been well characterized; however, their relatively high adenine and uridine (A+U) ribonucleotide content (for miRNA-9, miRNA-146a, and miRNA-132, 52, 59, and 65% A+U, respectively; Table 2), and their single-stranded character when not complexed with ribonucleoproteins or target mRNA 3′-UTRs make these miRNAs highly labile entities (20, 26).3

Alterations in the abundance of specific miRNAs appear to be associated with several neurological disorders including AD and stressed human neural cell models of AD (20, 26, 27). Central to AD pathogenesis is the observation that inflammatory processes contribute to the onset, progression, and propagation of this common disorder and that Aβ42 peptides, key pathological lesions of AD, are important inflammatory mediators, as are up-regulation of the cytokine IL-1β and the oxidative stress-inducing H2O2 (13, 14). Changes in global gene expression patterns in AD reveal increases in stress-related gene signaling and up-regulation in the expression of a family of proapoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes that include βAPP and IL-1β precursor (11–17). Cytokine, Aβ peptide, and/or oxidative stress of aging HN cells in primary culture emulates many of the up-regulated patterns of this same gene family and have been used as valuable in vitro models for studying the AD process (6, 10–17). The majority of pathogenic genes are positively up-regulated, in part, via the action of the transcription factor NF-κB that plays key roles in orchestrating inflammatory responses and cell fate decisions (6, 13, 21). How increased NF-κB signaling observed in AD brain and in stressed HN cells could account for gene down-regulation may in part be explained through the negative post-transcriptional regulatory controls imparted by specific miRNAs and their actions on discrete mRNA targets (20, 21, 28).

In this study we characterized miRNA expression in AD brain and in IL-1β-, Aβ42-, and H2O2-treated HN cells stressed up to one-third of their in vitro lifespan and found a significant up-regulation of an NF-κB-sensitive miRNA-146a and a down-regulation in a miRNA-146a mRNA target encoding CFH, an important repressor of the immune response and inflammatory signaling in the complement cascade. Six lines of evidence suggest that an NF-κB-sensitive miRNA-146a acts as a repressor of its CFH mRNA target: 1) up-regulation of NF-κB and miRNA-146a in two different regions of AD brain corresponds to down-regulation of CFH in those same brain regions (Figs. 1, 4, and 5); 2) IL-1β-, Aβ42-, and H2O2-stressed HN cells exhibit up-regulation of miRNA-146a corresponding to down-regulation of CFH in the same HN cell sample (Fig. 2); 3) human miRNA-146a is highly complementary to human CFH mRNA 3′-UTR (92% homology between 12 bp in the miRNA-146a 5′ region and CFH 3′-UTR; structural stability –27 kcal/mol; Fig. 3); 4) the NF-κB inhibitor PDTC abrogated miRNA-146a promoter-luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 6); 5) the substituted trans-stilbene resveratrol analog and NF-κB inhibitor CAY10512 also strongly inhibited miRNA-146a promoter-luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 6); and 6) an AM-146a specifically directed against miRNA-146a was found to restore both CFH mRNA and CFH protein to near control levels in H2O2-stressed HN cells (Fig. 7). The results suggest involvement of 1) oxidative stress and 2) miRNA-146a in the regulation of CFH, a key repressor protein in the complement cascade. Importantly, anti-miRNA strategies may be preferred over antisense mRNA strategies in neurological disorders such as AD because of the potential of miRNA to affect the regulation of multiple disease-related genes.

In agreement with these findings, other studies have shown miRNA-146a to be an NF-κB-sensitive endotoxin-responsive gene, induced in response to a variety of microbial components and inflammatory cytokines, and miRNA-146a also has been predicted to base pair with sequences in the 3′-UTRs of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 mRNAs (21, 29). miRNA-146a has also been proposed to function in the control of Toll-like receptor (TLR) and cytokine signaling through a negative feedback regulation loop involving down-regulation of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 levels (21). In AD TLRs provide a critical link between immune stimulants, such as Aβ42 peptide oligomers, their aggregation, and the initiation of host defense, and TLR activation modulates the release of inflammatory cytokines (5, 21, 29, 30). Interestingly, Aβ peptide stimulation of TLR3, TLR5, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR10 transcription has been found to be severely depressed in AD mononuclear cells, and down-regulation of TLRs may impair microglia-mediated clearance of Aβ deposits in the brain (31, 32).

Although an AD-related family of NF-κB-sensitive pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic genes is significantly up-regulated in AD brain (12–17), another population of genes such as those encoding inflammation regulators and primary synaptic and cytoskeletal-related markers appear to be significantly down-regulated (Refs. 10 and 13 and this report). For example synapsin II mRNA, encoding a neuron-specific, neurotransmitter release-regulating phosphor-protein that is significantly down-regulated in AD, has been identified as a target for miRNA-125b, and small increases in miRNA-125b in AD may have bearing on the synaptic protein deficits observed in affected AD tissues (20). Other researchers have described decreased miRNA-29 and miRNA-107 abundance that correlates with increased β-secretase expression in AD (27–29). Although altered miRNA-146a-mediated processing of mRNA populations may contribute to atypical CFH mRNA abundance and neural inflammation in AD brain, other miRNA-mediated signaling circuits may prove to be critical to AD development, pathogenesis, and neuropathology (30–34). Further miRNA studies in AD and in AD primary human neural cell models should delineate the full complement of the capacity of a miRNA to interact with select mRNAs and the coordinated role each of these plays in the regulation of brain gene expression in both healthy aging and in neurological disease.

In summary, dysfunctional gene regulation in AD brain has been attributed to disease-specific changes in brain chromatin structure, metal-ion induced genotoxicity, gene mutations in coding and regulatory regions of AD-related genes, genetic changes induced by the progressively deposited lesions that characterize AD, and other aberrant neuromolecular processes (12–16, 20, 22, 25, 26). These data are the first to suggest that the up-regulation of miRNA-146a abundance in AD brain and in stressed human brain cells in primary culture are linked to a repression of CFH bioavailability and suggest that the misregulation of specific miRNAs in AD brain contributes to inflammatory pathology. Importantly, because brain tissues are composed of multiple neuronal, glial, vascular, and other cell types, the contributions of each brain cell type to miRNA production and speciation remain to be elucidated. Investigations involving systematic, computational nucleic acid sequence examination of the interaction of brain-specific and brain-enriched miRNAs with the 3′-UTRs of target neural mRNAs, and validation through molecular techniques, especially those whose levels are altered in aging and in AD, should provide further insight into the role of miRNAs in the development, progression, and propagation of AD neuropathology (18, 20, 26, 35–38). The use of directed anti-miRNA strategies to repress the effects of specifically up-regulated miRNAs may be an effective therapeutic approach against inflammation and related pathogenic signaling in stressed brain cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Taganov and D. Baltimore for the use of the NF-κB-containing pre-miRNA-146a promoter-luciferase reporter vector (A547; Addgene, Cambridge, MA) and controls, and to Dr. Hilary Thompson, Yuan Yuan Li, and Darlene Guillot for expert statistical analysis and technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AG18031. This work was also supported by a Translational Research Initiative grant from Louisiana State University. Part of this work was presented at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology annual meeting in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, April 28, 2008. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AD, Alzheimer disease; UTR, untranslated region; 5SRNA, 5S ribosomal RNA; Aβ, amyloid β; CFH, complement factor H; HN, human neural; mRNA, messenger RNA; miRNA, micro RNA; PDTC, pyrollidine dithiocarbamate; IL, interleukin; HNMM, human neural maintenance medium; ANOVA, analysis of variance; PBN, phenyl butyl nitrone; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

W. J. Lukiw, Y. Zhao, and J. G. Cui, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Jellinger, K. A. (2006) J. Alzheimers Dis. 9 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLegge, M. H., and Smoke, A. (2008) Nutr. Clin. Pract. 23 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Infante-Duarte, C., Waiczies, S., Wuerfel, J., and Zipp, F. (2008) J. Mol. Med. 86 975–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi, Q., and Gibson, G. E. (2007) Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 21 276–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasto, S., Candore, G., Duro, G., Lio, D., Grimaldi, M. P., and Caruso, C. (2007) Pharmacogenomics 8 1735–1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colangelo, V., Schurr, J., Ball, M. J., Pelaez, R. P., Bazan, N. G., and Lukiw, W. J. (2002) J. Neurosci. Res. 70 462–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minghetti, L. (2007) Subcell. Biochem. 42 127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lio, D., Scola, L., Romano, G. C., Candore, G., and Caruso, C. (2006) Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 18 163–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho, G. J., Drego, R., Hakimian, E., and Masliah, E. (2005) Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 4 247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukiw, W. J., and Bazan, N. G. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34 1277–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazan, N. G., and Lukiw, W. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 30359–30367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustincich, S., Sandelin, A., Plessy, C., Katayama, S., Simone, R., Lazarevic, D., Hayashizaki, Y., and Carninci, P. (2006) J. Physiol. 575 321–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukiw, W. J., Rogaev, E. I., and Bazan, N. G. (2001) Alzheimer Rep. 3 233–245 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukiw, W. J. (2004) Neurochem. Res. 29 1287–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui, J. G., Hill, J. M., Zhao, Y., and Lukiw, W. J. (2007) Neuroreport 18 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mufson, E. J., Counts, S. E., Che, S., and Ginsberg, S. D. (2006) Prog. Brain Res. 158 197–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loring, J. F., Wen, X., Lee, J. M., Seilhamer, J., and Somogyi, R. (2001) DNA Cell Biol. 20 683–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson, P. T., Wang, W. X., and Rajeev, B. W. (2008) Brain Pathol. 18 130–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh, S. K. (2007) Pharmaco-genomics 8 971–978 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukiw, W. J. (2007) Neuroreport 18 297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taganov, K. D., Boldin, M. P., Chang, K. J., and Baltimore, D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 12481–12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukiw, W. J., Cui, J. G., Marcheselli, V. L., Bodker, M., Botkjaer, A., Gotlinger, K., and Bazan, N. G. (2005) J. Clin. Investig. 115 2774–2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sempere, L. F., Freemantle, S., Pitha-Rowe, I., Moss, E., Dmitrovsky, E., and Ambros, V. (2004) Genome Biol. 5 R13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schratt, G. M., Tuebing, F., Nigh, E. A., Kane, C. G., Sabatini, M. E., Kiebler, M., and Greenberg, M. E. (2006) Nature 439 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogaev, E. I. (2005) Biochemistry. 70 1404–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukiw, W. J., and Pogue, A. I. (2007) J. Inorg. Biochem. 101 1265–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, W. X., Rajeev, B. W., Stromberg, A. J., Ren, N., Tang, G., Huang, Q., Rigoutsos, I., and Nelson, P. T. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28 1213–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hébert, S. S., Horré, K., Nicolaï, L., Papadopoulou, A. S., Mandemakers, W., Silahtaroglu, A. N., Kauppinen, S., Delacourte, A., and De Strooper, B. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 6415–6420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, V. N. (2005) Mol. Cells 19 1–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taganov, K. D., Boldin, M. P., and Baltimore, D. (2007) Immunity 26 133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tahara, K., Kim, H. D., Jin, J. J., Maxwell, J. A., Li, L., and Fukuchi, K. (2006) Brain 129 3006–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Letiembre, M., Hao, W., Liu, Y., Walter, S., Mihaljevic, I., Rivest, S., Hartmann, T., and Fassbender, K. (2007) Neuroscience 146 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connell, R. M., Taganov, K. D., Boldin, M. P., Cheng, G., and Baltimore, D. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 1604–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudder, A., and Novak, R. F. (2008) Toxicol Sci. 103 228–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson, P. T., and Keller, J. N. (2007) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66 461–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobert, O. (2008) Science 319 1785–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, Y., Cui, Jian-Guo, and Lukiw, W. J. (2006) Mol. Neurobiol. 34 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niwa, R., Zhou, F., Li, C., and Slack, F. J. (2008) Dev. Biol. 315 418–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]