Abstract

Cardiac myocyte intracellular calcium varies beat-to-beat and calmodulin (CaM) transduces Ca2+ signals to regulate many cellular processes (e.g. via CaM targets such as CaM-dependent kinase and calcineurin). However, little is known about the dynamics of how CaM targets process the Ca2+ signals to generate appropriate biological responses in the heart. We hypothesized that the different affinities of CaM targets for the Ca2+-bound CaM (Ca2+-CaM) shape their actions through dynamic and tonic interactions in response to the repetitive Ca2+ signals in myocytes. To test our hypothesis, we used two fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based biosensors, BsCaM-45 (Kd = ∼45 nm) and BsCaM-2 (Kd = ∼2 nm), to monitor the real time Ca2+-CaM dynamics at low and high affinity CaM targets in paced adult ventricular myocytes. Compared with BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45 tracks the beat-to-beat Ca2+-CaM alterations more closely following the Ca2+ oscillations at each myocyte contraction. When pacing frequency is raised from 0.1 to 1.0 Hz, the higher affinity BsCaM-2 demonstrates significant elevation of diastolic Ca2+-CaM binding compared with the lower affinity BsCaM-45. Biochemically detailed computational models of Ca2+-CaM biosensors in beating cardiac myocytes revealed that the different Ca2+-CaM binding affinities of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 are sufficient to predict their differing kinetics and diastolic integration. Thus, data from both experiments and computational modeling suggest that CaM targets with low versus high Ca2+-CaM affinities (like CaM-dependent kinase versus calcineurin) respond differentially to the same Ca2+ signal (phasic versus integrating), presumably tuned appropriately for their respective and distinct Ca2+ signaling pathways.

Calcium is a well recognized diffusible messenger in many cell types (1). Indeed, Ca2+ regulates multiple biological responses in cardiomyocytes, where cytosolic Ca2+ oscillates in the range of 0.1–1 μm on a beat to beat basis (2). Calmodulin (CaM),2 a ubiquitous Ca2+-sensing protein (3), is an important Ca2+ signal transducer in the heart. It is well established that the activated form of CaM, Ca2+-CaM, modulates the function of various downstream targets (4) including ion channels (5–7) and enzymes such as CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (8), myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (9), nitricoxide synthase (10), and CaM-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) (11), which play central roles in diverse cellular processes. For example, CaMKII is implicated in regulation of the excitation-contraction coupling (8, 12) and apoptosis in the heart (13, 14), whereas CaN dephosphorylates transcription factors to regulate gene expression related to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (11). Despite the wide appreciation of the importance of Ca, CaM, and CaM targets on cardiac myocyte function, an intriguing question remains unsolved about how CaM and its target proteins differentiate Ca2+ signals to ensure the appropriate cellular responses in the heart.

The concentration of free CaM in adult ventricular myocytes is ∼50–100 nm, which is only 1–2% of the total myocyte CaM (15). Thus, the pool of free CaM is limited given the abundance of CaM targets in muscle cells (16). As a result, there is likely intense competition among CaM targets for CaM activation in response to Ca2+ signals in cardiomyocytes. Consequently, the action of different CaM targets in processing Ca2+ signals may be at least partially determined by their respective affinities for Ca2+-CaM. There is an extensive range of affinities for Ca2+-CaM among CaM targets (Kd values vary from ∼0.1 to >100 nm) (4). For instance, CaN has a particularly high affinity (Kd = ∼0.1 nm) (17) for Ca2+-CaM, whereas the affinity of CaMKII for Ca2+-CaM is much lower (Kd =∼50 nm) (18). It has been shown that CaN responds to sustained, low amplitude Ca2+ signals in lymphocytes and transduces these signals into the activation of nuclear transcriptional factor NFAT (19). In skeletal muscle, activation of CaN caused by sustained Ca2+ signals (evoked by motoneuron stimulation) and subsequent nuclear translocation of NFAT has been suggested to modulate fiber type-specific gene expression (20). On the other hand, CaMKII is activated preferentially by transient, high amplitude Ca2+ spikes and can undergo autophosphorylation switching it to a prolonged Ca2+ independent active state (21). It is found that activation of CaMKII can produce a memory with frequency and amplitude in neurons (22, 23) and skeletal muscle (24). However, there is limited understanding of the potential role that the different Ca2+-CaM affinities of the CaM targets, especially CaMKII and CaN, may play in decoding the Ca2+ signals in the cardiomyocyte.

Persechini and co-workers (25–29) have recently developed fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensors allowing real time studies on the interaction of CaM with CaM targets in response to Ca2+ signals in intact cells. These biosensors work by detecting the changes of FRET between two green fluorescent protein variants, a donor (enhanced CFP) and an acceptor (enhanced YFP) connected by a linker, which is derived from the Ca2+-CaM-binding domain of the smooth muscle MLCK. Site mutations of the linker sequence confer different Ca2+-CaM affinities to the biosensors (25). Two biosensors (BsCaM-45, Kd =∼45 nm versus BsCaM-2, Kd =∼2 nm) are of particular interest because their apparent Ca2+-CaM affinities are similar to those of the low affinity targets (e.g. CaMKII) and those of the high affinity targets (e.g. CaN), respectively. Our initial report using BsCaM-45 demonstrated the feasibility of detecting dynamic beat-to-beat Ca2+-CaM changes in adult ventricular myocytes (30). The BsCaM-2 sensor, with higher Ca2+-CaM affinity, has been used to measure Ca2+-CaM changes in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells (25) and endothelial cells (28). Here, we compare BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 biosensors to test the hypothesis that the different Ca2+-CaM affinities of CaM targets may dictate their dynamic and tonic binding to Ca2+-CaM in adult ventricular myocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Di-8-Anepps, Fluo-4AM, and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate CaM (F-CaM) were from Molecular Probes. High purity calmodulin were from Calbiochem. All other chemicals were from Sigma.

Construction of Adenoviral Vectors Encoding Biosensors—The BsCaM-2 plasmid (29), a kind gift from Dr. A. Persechini (University of Missouri-Kansas City, MO), was incorporated in adenoviruses to ensure the high infection efficiency in the terminally differentiated adult ventricular myocytes. The commercially available AdEasy™ adenoviral vector system (Qbiogene, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) was used to construct the adenoviral vector encoding the BsCaM-2 biosensor following the manufacturer's instructions. The BsCaM-45 adenoviral vector was previously constructed in our lab (30).

HEK293 Cell Transfection—HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 5% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin for 24 h and then transiently transfected with expression plasmids for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 using the mammalian transfection kit (Stratagene). The cells were cultured for an additional 24 h prior to experiments.

In Vitro Fluorescence Measurements—Fluorescence measurements of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 were performed using a spectrofluorometer (SLM, model LS-8100). Excitation and emission slits were set at 4 nm. An excitation wavelength of 430 nm was used, and dual photon counting emission detectors were set at 480 nm (F480) and 530 nm (F530), respectively. The cytosolic fraction of the transfected HEK cells were diluted in Ca2+-free internal solution (in 100 mm potassium asparate, 30 mm KCl, 20 mm HEPES, 5 mm 5′-ATP-DiTris, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm NaCl, 3 mm KH2PO4, 5 mm sodium pyruvic acid, 0.5 mm K4-BAPTA, pH 7.2, at 23 °C) with the biosensor concentration ∼0.8–4.8 nm. Standard Ca2+ solutions were added to achieve free Ca2+ of 50 μm according to the calculation with the Max-Chelator program. Incremental addition of CaM was used to reach various concentrations as indicated in the experiments. CaM binding affinity (Kd) of biosensors were estimated using nonlinear regression analysis (Prizm 4.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Myocyte Isolation and Adenoviral Infection—Adult rabbit ventricular myocytes were isolated as previously described (31). All of the procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Loyola University Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Myocytes were seeded on laminin-coated culture inserts in serum-free PC-1™ medium (Lonza Group Ltd.) supplemented with penicillin (400 units/ml) and streptomycin (400 μg/ml). After 1 h of incubation in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for cell attachment, the nonadherent myocytes were washed off. Then the myocytes were infected for 2 h at multiplicity of infection of 10–100 with adenovirus expressing BsCaM-2 or BsCaM-45 and subsequent fresh medium replacement with one further time change before the experiment ∼36–48 h later. Adenovirus expressing CaM (gift from Dr. David Yue, Johns Hopkins University) was used to co-infect cells to boost the FRET signals as previously reported (30).

Confocal Microscopy Imaging—Inserts containing the cultured myocytes were mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Zeiss, LSM5 Pascal) equipped with a 40× 1.4 NA water immersion objective lens. The superfusate for experiments was Tyrode solution (140 mm NaCl, 4 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.4, at 23 °C). CFP emission fluorescence at 485 ± 15 nm was measured by confocal microscopy with argon laser excitation at 458 nm, indicating infection and localization. Di-8-Anepps, a dye staining the T-tubules of myocytes, was excited with argon laser excitation at 488 nm with emission at >560 nm to avoid fluorescence signal cross-talk. YFP excitation was at 514 nm, and emitted fluorescence was measured at >530 nm. Acceptor photobleaching was performed by YFP excitation at 514 nm (laser at power of 90% for 45 s). Image-J software was used for image analysis.

Dynamic Fluorescence Measurements in Ventricular Myocytes—The cells were superfused with normal Tyrode solution (23 °C) or in the presence of 1 μm isoproterenol (Iso). The cells were field stimulated at 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 Hz. Beat-to-beat fluorescence signals of CFP (F480) and YFP (F530) from the infected cells were monitored using a standard epifluorescence microscope, attached to two photomultiplier tubes allowing simultaneous detection of CFP and YFP emission. Customized filters included: a CFP exciter 430 ± 10 nm, a 505-nm long pass dichroic filter to separate CFP signal from YFP signals, a CFP emitter 480 ± 10 nm, and a YFP emitter 535 ± 15 nm (Chroma, Brattleboro, VT). FRET signals were presented as the ratio of F480 to F530 (F480/F530 or R), indicating the Ca2+-CaM interaction with the biosensors. For intracellular Ca2+ measurements ([Ca2+]i), the cells were loaded for 20 min with the membrane-permeant fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM (6 μm). Fluo-4 was excited at 480 ± 5 nm, and emission was measured using a 535 ± 20 nm bandpass filter. [Ca2+]i signals are presented as background-subtracted normalized fluorescence (F/Fo) where F is the fluorescence intensity and Fo is the resting fluorescence recorded under steady state conditions. All of the fluorescence signals were recorded with the Axon pClamp8 software and analyzed using custom software designed by Dr. Eckard Picht.

F-CaM Binding Experiments in Permeabilized Ventricular Myocytes—After settling in Tyrode solution, some myocytes were switched to internal solution (50 nm free calcium) containing saponin (50 μg/ml) for 20 s to permeabilize the sarcolemma (15). Internal solutions with various levels of F-CaM as indicated were immediately washed in, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for at least 4 h to reach steady state. Confocal images of F-CaM were recorded using a laser excitation wavelength of 488 nm and the emission wavelength of 500–530 nm. Note that the F-CaM signal could be calibrated based on the known bath concentration and fluorescence (15). The apparent CaM binding affinity of permeabilized cell was estimated using nonlinear regression analysis with Prizm 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego CA).

Statistics—Pooled data are represented as the means ± S.E. Statistical comparisons were made using repeated two-way analysis of variance, paired, and unpaired Student's t test where applicable. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

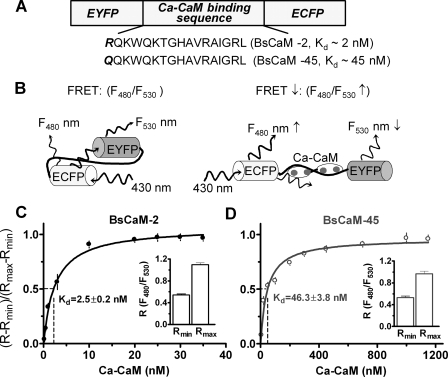

CaM-dependent FRET Responses of Ca2+-CaM Biosensors—The goal of the current study is to test the hypothesis that the different affinities of CaM targets for Ca2+-CaM alter the transduction of Ca2+ signals to appropriate cellular processes in adult cardiomyocytes via the Ca2+-CaM-CaM target signaling axis. To accomplish this, two versions of FRET-based biosensors with different affinities for Ca2+-CaM were established (Fig. 1A). In the absence of Ca2+-CaM binding to the linker of the biosensors, excitation of CFP at 430 nm generates FRET between the CFP and YFP. Upon binding of Ca2+-CaM to the biosensors, the CFP and YFP move apart, and FRET is reduced because of its strong dependence on the CFP to YFP distance. Reduced FRET is shown as an increased ratio of fluorescence emission of CFP at 480 nm (F480) to YFP at 530 nm (F530). Thus, the ratio of F480 to F530 (F480/F530) is a read-out of Ca2+-CaM interaction with the biosensors (Fig. 1B). To ensure that Ca2+-CaM-dependent FRET changes reflect the expected biosensor affinities, the F480/F530 signals for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 were assessed in the cytosolic fraction of transfected HEK cells upon sequential addition of CaM in the presence of 50 μm Ca. In the absence of Ca2+-CaM, the minimal F480/F530 (Rmin) for BsCaM-2 is 0.542 ± 0.042 (n = 5) versus BsCaM-45 (0.529 ± 0.058, n = 5). At saturating Ca2+-CaM, the maximal ratio (Rmax) of BsCaM-2 is 1.094 ± 0.072 versus BsCaM-45 (0.965 ± 0.102), indicating a similar dynamic range of the two sensors. The apparent affinity for Ca2+-CaM (as Kd) assessed by FRET reduction for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45, was 2.5 ± 0.2 nm (Fig. 1C) and 46.3 ± 3.8 nm (Fig. 1D), respectively.

FIGURE 1.

FRET-based Ca2+-CaM biosensor. A, the domain structure of Ca2+-CaM biosensor. Two versions of the biosensor were developed: BsCaM-2 with a high Ca2+-CaM binding affinity versus BsCaM-45 with a lower Ca2+-CaM binding affinity similar to that of CaMKII. B, diagram showing the Ca2+-CaM-dependent FRET changes of the biosensors. C and D, titration of BsCaM-2 (C) and BsCaM-45 (D) in the presence of 50 μm Ca2+ with increasing concentrations of CaM. The data were fitted to a standard single-site binding model. The Kd values were obtained as 2.5 nm (BsCaM-2) and 46.3 nm (BsCaM-45), respectively. R is the ratio of F480 to F530. Rmin (the minimal ratio of biosensor in absence of Ca2+-CaM) and Rmax (the maximal ratio of biosensor saturated with Ca2+-CaM) are shown in the insets.

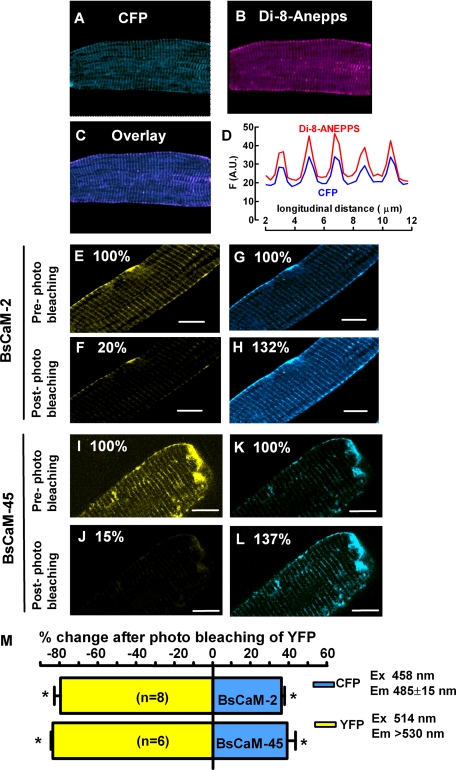

Detection of Biosensor Expression and FRET in Adult Ventricular Myocytes—Adult rabbit ventricular myocytes were cultured for 36–48 h to obtain sufficient expression of the biosensors without detectable cellular toxicity. The expression of both BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 sensors exhibited striated patterns as shown in the images of Fig. 2. To test whether this striated localization of biosensors is at Z-lines versus M-lines, myocytes were stained with the membrane indicator Di-8-Anepps to identify transverse tubules, which occur at the Z-lines (Fig. 2B). The line plot (Fig. 2D) of the superimposed images (Fig. 2C) shows that Di-8-Anepps and CFP signals of the biosensors overlapped spatially and that the distance between striations was about 1.9 μm (the sarcomere length). This suggests that the biosensors are relatively concentrated at Z-lines.

FIGURE 2.

FRET signals of the Ca2+-CaM biosensors in resting adult ventricular myocytes. A–D, relative localization of Ca2+-CaM biosensors at T-tubule/Z-line in adult rabbit ventricular myocytes. The cells were also loaded with Di-8-Anepps, marking T-tubules. A, images of CFP (excitation 458 nm and emission 485–500 nm). B, images of Di-8-Anepps (excitation, 488 nm, and emission, >560 nm). C, overlay of the CFP and Di-8-Anepps images. D, line profile of the fluorescence intensity of CFP and Di-8-Anepps. E–L, acceptor (YFP) photobleach was achieved by exposing cells to laser light of 514 nm at maximal intensity for 30–45 s. The increase in donor (CFP) fluorescence intensity after acceptor photobleach implies FRET between CFP and YFP. E–H, cells expressing BsCaM-2. I–L, cells expressing BsCaM-45. CFP: excitation, 458 nm, and emission, 470–500 nm; YFP: excitation, 514 nm, and emission, > 530 nm. M, average percentage changes of increases in donor (CFP, blue) and decreases in acceptor (YFP, yellow) fluorescence intensities. Scale bar, 4 μm in all images. *, p < 0.05 versus pre-photo bleaching.

A critical hallmark of FRET is an increase in donor (CFP) fluorescence upon bleaching of the acceptor (YFP) (32). Therefore, acceptor YFP photo-bleaching experiments were performed with quiescent myocytes superfused with normal Tyrode's solution. Fig. 2 (E–H) illustrates that photobleach of YFP (with the 514-nm laser line; note the ∼80% decrease in YFP fluorescence) increased CFP donor fluorescence by ∼30% in a rabbit ventricular myocyte expressing BsCaM-2. Comparable results were found in cells expressing BsCaM-45 (Fig. 2, I–L). As shown in Fig. 2M, the mean values for increased CFP fluorescence after YFP photobleach are 32 ± 1.3% (n = 8) and 29 ± 1.5% (n = 8) for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45, respectively. Therefore, both BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 sensors have similar FRET efficiency in the infected myocytes.

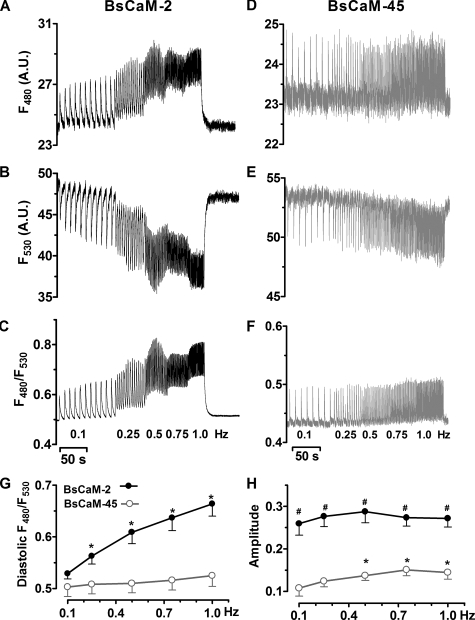

Frequency-dependent Diastolic Ca2+-CaM Integration in Paced Ventricular Myocytes—A unique character of Ca2+ signals in adult ventricular myocyte is the rhythmic Ca2+ oscillation occurring with each heartbeat (2). We expected that the FRET based biosensors would detect the beat-to-beat Ca2+-CaM changes in cardiomyocytes. Indeed, using epifluorescence dual emission microscopy in field-stimulated intact adult ventricular myocytes, we found dynamic alterations of the emission of both CFP (F480), YFP (F530), and the corresponding F480/F530 in cells expressing either BsCaM-2 (Fig. 3, A–C) or BsCaM-45 (Fig. 3, D–F) with supplemental CaM via adenoviral infection, which was previously found to overcome the endogenous decline in CaM expression during cell culture (30). The simultaneous yet opposite changes of F480 and F530 at each cell contraction (Fig. 3, A, B, D, and E) demonstrate that the fluorescence responses (Fig. 3, C and F) are not due to movement artifact. Moreover, appropriate control experiments showed that the beat-to-beat F480/F530 signal was still observed in the presence of cytochalastin D, an inhibitor of contraction (33) (not shown), corroborating the dynamic FRET signal as a reliable indicator of Ca2+-CaM change in the paced cells.

FIGURE 3.

Frequency-dependent Ca2+-CaM signals on a beat-to-beat basis in adult cardiomyocytes expressing either BsCaM-2 or BsCaM-45. A–C, fluorescence signals from CFP emission (F480), YFP emission (F530), and the corresponding ratio (F480/F530) of BsCaM-2. D–F, signals from F480, F530, and F480/F530 of BsCaM-45. G, averaged data of frequency-dependent diastolic levels of F480/F530 of BsCaM-2 (•) and BsCaM-45 (○). n = 6–10. *, p < 0.05 versus 0.1 Hz in the same group. H, averaged data of amplitude of BsCaM-2 (•) and BsCaM-45 (○). Amplitude: (Rsystolic – Rdiastolic)/(Rmax – Rmin). n = 6–10. *, p < 0.05 versus 0.1 Hz in the same group; #, p < 0.05 versus BsCaM-45 at the same frequency.

The frequency of Ca2+ signals triggered by different extracellular stimuli has been suggested to influence the resulting biologic reactions in several cell types such as neurons (22, 23) and skeletal muscle (9, 20, 24, 34). Along this line, we studied the changes of FRET signals of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 in response to pacing at various rates (which drives oscillations of [Ca2+]i). As the pacing rate increased from 0.1 to 1 Hz, there was a clear frequency-dependent F480/F530 signal integration in BsCaM-2 sensor as shown by the significant elevation of diastolic F480/F530 levels (Fig. 3C). In contrast, there was only a tendency of diastolic F480/F530 integration of BsCaM-45 at 1 Hz (Fig. 3F). A similar slight integration of diastolic Ca2+ signal detected by the Fluo-4 AM Ca2+ indicator was observed in parallel experiments using control cells without biosensor adenoviral infection (not shown). Average diastolic Ca2+-CaM signal levels of myocytes paced at increasing frequencies are summarized in Fig. 3G. The diastolic F480/F530 level of the higher affinity BsCaM-2 sensor was increased at 1 Hz (125% ± 2.9% versus 0.1 Hz, n = 10, p < 0.05), whereas the lower affinity sensor BsCaM-45 (like CaMKII) turned on and off almost completely each beat with only a slight diastolic increase at 1.0 Hz (103% ± 3.1%, versus 0.1 Hz, n = 10, p > 0.05). The BsCaM-2 amplitude of F480/F530 oscillations ((Rsystolic – Rdiastolic)/(Rmax – Rmin)), was ∼2.5-fold larger than that of BsCaM-45 in beating myocytes (Fig. 3H), despite similar dynamic ranges of Ca2+-CaM-dependent FRET (Rmax – Rmin) for the sensors (Fig. 1, C and D). As the pacing frequency increased, BsCaM-45 signal amplitude tended to increase, but not significantly so for BsCaM-2 (Fig. 3H).

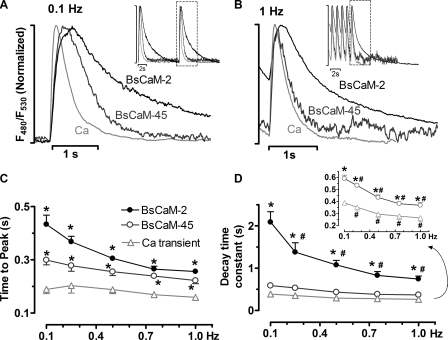

Dynamic Properties of Ca2+-CaM Signals Detected in Living Cardiomyocytes—To better appreciate the different dynamic properties of the biosensors in response to repetitive Ca2+ signals, the normalized F480/F530 signals of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transients were superimposed with expanded time scales (Fig. 4A). When cells were paced at 0.1 Hz, the Ca2+-CaM signals of both BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 have a rising phase closely following the Ca2+ transient, whereas they reached the peak slower than the Ca2+ transient (Fig. 4C). With respect to the signal decline at 0.1 Hz, BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 have slower decay compared with the Ca2+ transient, which was demonstrated by their τ (time constant of decay, s): BsCaM-2, 2.09 ± 0.25; BsCaM-45, 0.48 ± 0.03; and Ca2+ transient, 0.36 ± 0.02. Therefore, at 0.1 Hz, Ca2+-CaM bound to BsCaM-2 more tightly and thus presumably dissociated slower than for BsCaM-45. This was also true when the cells were paced at 1 Hz as shown in Fig. 4B, τ (s): BsCaM-2, 0.75 ± 0.07; BsCaM-45, 0.34 ± 0.01; and Ca2+ transient, 0.24 ± 0.04. Notably, as the pacing frequency increased from 0.1 Hz to 1.0 Hz, both BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 revealed an accelerated Ca2+-CaM signal decay in association with the enhanced [Ca2+]i decline (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Dynamics of Ca2+-CaM signals from FRET-based biosensors in adult cardiomyocytes. A and B, normalized tracings of fluorescence signals of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transients from cells paced at 0.1 Hz (A) and 1.0 Hz (B). Inset, tracings with representative beats indicated. C, averaged data of time to peak of the F480/F530. n = 6–10. *, p < 0.05 versus Ca2+ transient at the same frequency. D, averaged data of time constant (τ) of the decay of the F480/F530. The data of BsCaM-45 and Ca2+ transient was zoomed in and showed as inset. n = 6–10. *, p < 0.05 versus Ca2+ transient at the same frequency; #, p < 0.05 versus 0.1 Hz in the same group.

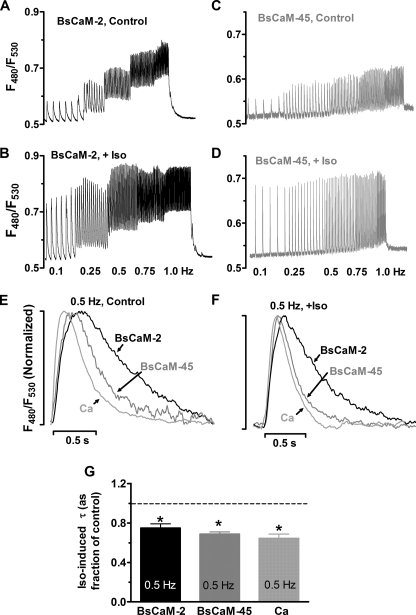

Effects of β-Adrenergic Stimulation on the Beat-to-beat Changes of Ca2+-CaM Signals—Cardiac Ca2+ oscillations are regulated not only by pacing frequency but also by β-adrenergic stimulation, which modulates Ca2+ signal amplitude and accelerates Ca2+ transient decline via multiple pathways, including Ca2+-CaM targets (35). Therefore, the responses of biosensors with different Ca2+-CaM affinities to β-adrenergic stimulation were explored by pacing cells in the presence of 1 μm Iso. The amplitude of Ca2+-CaM signals of both sensors were significantly increased upon Iso stimulation at all pacing frequencies (Fig. 5, A–D, e.g. at 0.5 Hz, BsCaM-2: 186% ± 15% versus control, p < 0.05; BsCaM-45: 236% ± 28% versus control, p < 0.05). Representative F480/F530 traces showed that the frequency-dependent diastolic elevation of Ca2+-CaM signal in BsCaM-2 was sustained with Iso stimulation (Fig. 5, A and B), whereas Iso-stimulated BsCaM-45 kinetics still exhibited more modest diastolic elevation at increased rates (Fig. 5, C and D). Quantitative comparisons of the kinetics of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transients at 0.5 Hz pacing rate with and without β-adrenergic stimulation are shown in Fig. 5 (E and F). In control cells, BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 had slower decay compared with the Ca2+ transient (Fig. 5E), which is consistent with our findings for 0.1 and 1 Hz described above. Upon application of Iso, the rates of decline of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transient were all enhanced (Fig. 5G). However, their relative positions in the superimposed tracings was still largely maintained (Fig. 5F) compared with control (Fig. 5E).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of β-adrenergic stimulation on the beat-to-beat changes of Ca2+-CaM signals. A–D, representative tracings of Ca2+-CaM signals from cells expressing BsCaM-2 or BsCaM-45 without (control, A and C) or with β-adrenergic stimulation using 1 μm Iso (+Iso, B and D). E and F, superimposed normalized tracings of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45 and Ca2+ transients when cells were paced at 0.5 Hz under control conditions (E) or 1 μm Iso (F). G, averaged data of the Iso-induced signal decay time constant (τ) of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transient. n = 5–6. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

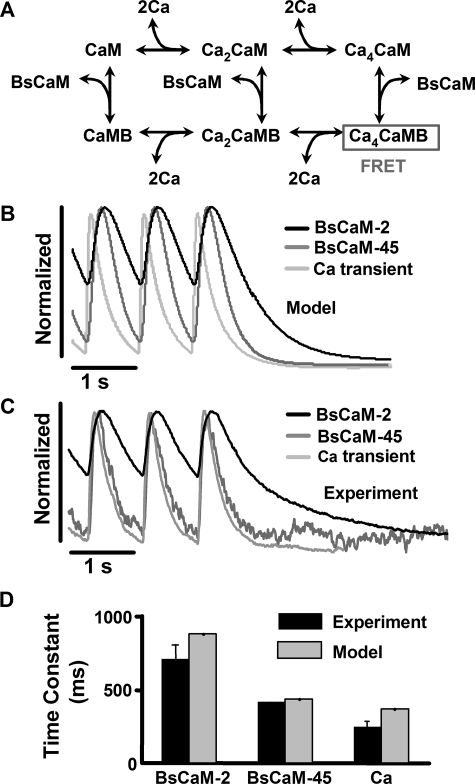

Mathematical Model of CaM Biosensor Dynamics in Ventricular Myocytes—To better understand the biochemical basis for differential activation of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45, we developed a mathematical model of the interaction of these biosensors with CaM (Fig. 6A), which we embedded in a previously described detailed model of Ca2+ handling in the adult rabbit ventricular myocyte (36). The present model for CaM and CaM biosensors was adapted from our recent compartmental models (dyadic cleft versus cytosol) of CaM activation, CaM buffering, and two specific CaM targets (CaMKII and CaN) (37). Reactions of Ca2+ binding to CaM are modeled as previously (37), with sequential binding of two Ca2+ first to the C-terminal sites of CaM and then two Ca2+ to the N-terminal sites at lower affinity. The remaining reactions were based on biochemical data of CaM interactions with MLCK (whose CaM-binding domain is the linker for the biosensors used here) or when available, BsCaM-2 itself. For BsCaM-45, similar parameters are used assuming that the decreased affinity is due to an increased off rate of Ca4CaM with unaltered on rate. We assume that FRET only occurs with Ca4CaM bound to BsCaM. Because we overexpressed CaM in our experiments (which restores endogenous CaM levels or increases ∼2-fold) (30), we also simulated conditions with an extra 6 μm CaM. Simulations at either CaM level produced very similar kinetic results but with lower amplitude signals at lower [CaM]. Complete model equations and parameter values along with their sources from the biochemical literature are provided in the supplemental data. Note that none of these parameters were curve fit or adjusted to mimic the BsCaM myocyte data obtained in our experiments.

FIGURE 6.

Computational model of the dynamic responses of Ca2+-CaM biosensors in cardiac myocytes. A, reaction scheme of the mechanistic model of Ca, CaM, and Ca2+-CaM biosensors, which are embedded in a model of Ca2+ handling in the adult ventricular myocyte (36). B, model-predicted kinetics of cytosolic BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transients at 1 Hz from the model are remarkably close to corresponding experimental measurements (C). D, comparison of the decay time constant of BsCaM-2, BsCaM-45, and Ca2+ transient at 1 Hz between model and experiments.

Simulations of BsCaM kinetics during 1 Hz pacing showed that BsCaM-45 FRET signal decays much more quickly than BsCaM-2 (Fig. 6B), remarkably consistent with what we observe experimentally without any curve fitting (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, predicted overall decay rates of both BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 (1.4 and 2.3 s–1, respectively) were significantly faster than the rate constants for Ca4CaM dissociation from BsCaM-Ca4CaM complex (0.05 and 1.5 s–1, respectively). This indicates that Ca2+ dissociation from the complex (rather than Ca4CaM dissociation) may be the dominant BsCaM deactivation pathway in the beating myocyte. Simulations in which Ca2+ dissociation was blocked produced greatly slowed inactivation, consistent with this interpretation. Ca2+ dissociation has been previously shown to be a significant inactivation pathway in experiments and models of purified CaM targets including MLCK (38, 39), CaMKII (40), and CaN (41).

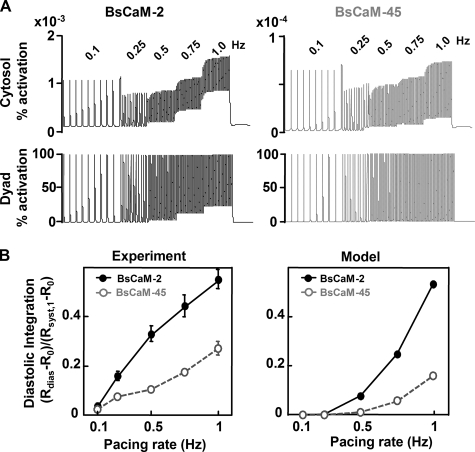

Next, we simulated BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 dynamics in response to a staircase of increasing pacing rates (0.1–1 Hz). BsCaM-2 exhibited significantly greater diastolic integration at increasing pacing rates compared with BsCaM-45 (Fig. 7A, upper panels), in a manner quite consistent with the experimental data (Figs. 3 and 7B) given that no curve fitting was used. This demonstrates that the biochemical mechanisms included in our model are sufficient to qualitatively predict differential signal integration and kinetics by BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45.

FIGURE 7.

Model-predicted diastolic integration of Ca2+-CaM signals for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 with increasing pacing rates. A, simulation of BsCaM-2 (left panels) and BsCaM-45 (right panels) kinetics in cytosolic (upper panels) and dyadic cleft (lower panels) compartments in response to increasing pacing rates from 0.1 to 1 Hz. B, comparison of cytosolic model predictions with experimental results of diastolic integration for BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45. Diastolic integration is quantified as the magnitude of diastolic signal compared with the systolic signal at 1 Hz: (Rdias – Ro)/(Rsyst,1 – Ro), where Rdias is the diastolic ratio at the indicated pacing rate, Ro is the ratio without pacing, and Rsyst,1 is the systolic ratio at the pacing rate of 1 Hz.

However, the amplitudes of model-predicted cytosolic BsCaM signals were smaller than what was observed experimentally. Given the localization data in Fig. 2A, some BsCaM biosensors may be located in regions of high local [Ca2+] signals (42). To determine whether BsCaM localization may explain the remaining discrepancy between model and experiment, we also simulated BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 in the dyadic cleft (Fig. 7A, lower panels), which predicted fully activated biosensors but with lesser diastolic integration and no gradual increase in systolic FRET ratio at higher pacing rates (Fig. 7A, lower panels). Although the experimental data is not fully explained by either BsCaM completely in the cytosol or completely in the dyadic cleft, it seems likely that some combination of these occurs. Another possible explanation for the smaller predicted amplitudes of BsCaM may be that free CaM may increase more than the expected from total CaM expression measurements (endogenous to 2-fold) (30). That is, if myocyte free CaM-binding sites are nearly saturated under basal endogenous conditions, then a doubling of total [CaM] may increase free [CaM] much more than 2-fold. This higher free [CaM] could then greatly enhance the ability of the sensors to compete for CaM in our experiments. Note that without CaM co-expression, FRET transients were not readily detectable (30).

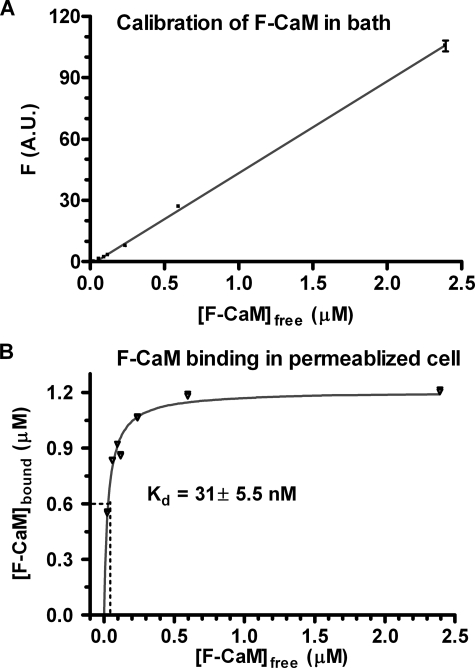

CaM Binding in Permeabilized Ventricular Myocytes—To test the overall CaM binding affinity in cardiac myocytes, we titrated permeabilized myocytes with fluorescent CaM (F-CaM) at 50 nm free [Ca2+]i using confocal microscopy (Fig. 8). The total [CaM] in the permeabilized myocyte can be calibrated by the fluorescence intensity of pixels in the extracellular space (Fig. 8A). We previously demonstrated (15) that when specific CaM sites were saturated (blocked) with nonfluorescent CaM, the apparent [F-CaM] in the myocyte space was nearly the same as [F-CaM] in the bath myocyte space (within 10%) over a wide range of [F-CaM]. We used this relationship (Fig. 8A) to calibrate the [F-CaM] in images where bath [F-CaM] is known and the cellular fluorescence is measured (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Calibration of F-CaM binding in permeabilized adult cardiomyocytes. A, the fluorescence of different [F-CaM] in internal solution (50 nm free Ca2+) was recorded by confocal microscopy and linear regression was shown (n = 10). B, F-CaM binding affinity in myocytes, which were permeabilized and followed by incubation of [F-CaM] in internal solution for 4–6 h. Fluorescence was taken after reaching the F-CaM binding steady status in the cells (n = 8–10), and the bound F-CaM (μm) was plotted according to A. Standard nonlinear regression analysis was performed to obtain the apparent Kd.

At 50 nm [Ca2+]i the apparent Kd for CaM with nonsoluble myocyte proteins is 31 ± 5.5 nm. This indicates that at the 62–100 nm free [CaM] and 6 μm total [CaM] in ventricular myocytes (15, 30), that endogenous CaM-binding sites would be 67–76% saturated (and ∼99% of total CaM is bound). If we then double the total CaM (e.g. from 6–12 μm), the endogenous sites (with 31 nm Kd) would be saturated, and free [CaM] could rise to 3–4 μm (i.e. >40-fold increase). Although it is surprising that endogenous CaM-binding sites seem near saturation at 50 nm [Ca2+]i, this may help explain why biosensor signal amplitude is higher than expected from the model.

We also estimated the sensor concentration in myocytes using two methods. First, we used semi-quantitative Western blots of myocyte lysates versus known amounts of green fluorescent protein (correcting for two green fluorescent proteins/sensor and myocyte protein concentration, 112 mg/ml myocyte). Second, we compared the fluorescence intensity (in confocal images) of known [YFP] with YFP signals in BsCaM expressing myocytes. Both methods yielded values ∼0.7 μmol/liter myocyte volume. This would add to endogenous Ca2+-CaM buffering and help explain why exogenous CaM was required for robust signals.

DISCUSSION

The biosensors used in our study are recombinant proteins that mimic endogenous CaM target proteins binding to Ca2+-CaM with different affinities (25). We measured FRET signals from these biosensors to assess real time interaction of CaM targets with Ca2+-CaM in response to the rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations in adult rabbit ventricular myocytes. Our measurements demonstrated that the higher affinity sensor BsCaM-2 (like CaN) binds Ca2+-CaM more tightly and therefore integrates repetitive Ca2+ signals in a tonic way, whereas the lower affinity sensor BsCaM-45 (like CaMKII) turns on and off more completely by binding to and dissociating from Ca2+-CaM with each contraction of the ventricular myocyte (i.e. in a phasic way). We could quantitatively predict these different behaviors of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 with a myocyte mathematical model using known biochemical differences in CaM affinity. Our study bridges experiments with different Ca2+-CaM affinity targets and modeling and implies that the different Ca2+-CaM affinities of CaM target proteins may provide an important mechanism for differential decoding of Ca2+ signals in myocytes. Considering the broad importance (and complexity) of CaM signaling in cardiac electrophysiology, excitation-contraction coupling, transcriptional regulation, and apoptosis, this study is a critical step in developing a more comprehensive understanding of Ca2+-CaM-dependent signaling in intact cardiac myocytes.

CaM Binding Integrates at High Affinity Targets (Like CaN) upon Increased Pacing in Myocytes—We showed diastolic accumulation of Ca2+-CaM bound to the higher affinity BsCaM-2 during field stimulation of myocytes (between 0.1 and 1 Hz), reflecting an integration of repetitive Ca2+ signals. Moreover, the frequency-dependent elevation of diastolic Ca2+-CaM signal from BsCaM-2 (0.1 Hz versus 1 Hz) was also observed with β-adrenergic stimulation, a physiological stimulus that enhances the amplitude and rate of decline of the Ca2+ transient in myocytes (35). These findings illustrate how high affinity CaM targets like BsCaM-2 (and CaN) can integrate repetitive Ca2+ signals in cardiac myocytes to generate a tonic component of their signaling output. Although it is oversimplified to consider the BsCaM-2 to be an analog of CaN because the apparent Ca2+-CaM affinity of CaN is ∼10-fold higher than that of BsCaM-2 (17), it is reasonable to speculate that the integration of Ca2+ signals by CaN may be even greater (see also Ref. 37). Moreover, the agreement here between kinetics of the BsCaM-2 sensor and the computational model give us confidence that the CaN kinetics predicted in our recent modeling study (37) may be reasonable.

Our findings of CaM signal integration in cardiac myocytes are consistent with prior work on MLCK. Frequency-dependent increases in myosin light chain phosphorylation have been explained by staircasing MLCK activity arising from the kinetic properties of the CaM-MLCK complex. This was first predicted in a mathematical model (9) and later demonstrated with a MLCK biosensor in skeletal muscle (34). Frequency-dependent integration of Ca2+ signals at high Ca2+-CaM affinity targets (such as CaN and MLCK) has been shown to be of functional importance in Ca2+-dependent pathways of lymphocytes (19) and skeletal muscle (9, 20, 34). In cardiac muscle, increasing evidence has shown the significance of CaN in regulation of hypertrophy and heart failure (11), where Ca2+ regulation is also often disrupted (43). Interestingly, overexpression of MLCK in cardiomyocytes results in attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy (44). Our finding of Ca2+ signal integration caused by the high Ca2+-CaM affinity of CaM targets will help develop a comprehensive picture of how cells distinguish between Ca2+ signaling through this pathway versus others.

CaM Binding to Low Affinity Targets (Like CaMKII) Exhibits Modest Integration—In contrast to the BsCaM-2 sensor, the BsCaM-45 sensor showed only a slight tendency toward frequency-dependent diastolic integration whether the cell was exposed to isoproterenol or not. The phasic changes of BsCaM-45 track the beat-to-beat Ca2+ transient much more closely than BsCaM-2. In particular, the decline of the Ca2+-CaM signal of BsCaM-45 is always faster than that of BsCaM-2, although not as fast as the Ca2+ transient. The different kinetic properties of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 are consistent with their respective Ca2+-CaM binding affinities, which are similar to that of CaN and CaMKII (especially for the latter). Furthermore, the difference in the time course of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 in response to the intracellular Ca2+ oscillation could indicate their distinctive patterns of activation in beating myocytes. Activation of CaMKII, preferentially by transient and large amplitude local Ca2+ spikes (21), has been implicated in CaMKII signaling at post-synaptic densities in neurons (22), in mediating local InsP3 receptor signaling in Ca2+-dependent cardiac transcriptional activation via HDAC5 nuclear export (45) and could even participate in frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation (46, 47). Thus, local high Ca2+-CaM signals may preferentially signal activation of low affinity CaM targets such as CaMKII (like BsCaM-45), and this may contribute to the ability of cardiac myocytes to use multiple Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways for different processes in the cell simultaneously.

It should also be noted that downstream CaMKII signaling can still exhibit integration or memory, even though BsCaM-45 did not show this appreciably. This is because the affinity of CaMKII for CaM can be increased by CaMKII autophosphorylation, which may prolong the active state of CaMKII versus BsCaM-45. However, we have included that behavior in our computational model (37), and with best estimates of these CaMKII properties CaMKII seems still to activate phasically to high local [Ca2+]i without much integration on the timescale of the heartbeat. Again our modeling and experimental data suggest that under normal conditions there is little progressive CaMKII autophosphorylation, unless the phosphatases are inhibited (37, 48). This does not preclude functional importance of CaMKII autophosphorylation in the heart, but this may be most important in pathophysiological setting like acidosis, ischemia/reperfusion (13, 49), or heart failure (50, 51). CaMKII can also phosphorylate many targets, and the lifetime and integration of those phosphorylation effects are controlled by a balance of kinase and phosphatase reactions, and these may differ among different targets and in different cellular environments (where local phosphatase and kinase activities vary). This is also true for high affinity CaM targets such as CaN, where the integrated effect of its phosphatase activity on downstream targets (e.g. NFAT) will be dictated by the kinase-phosphatase balance for a given target, location, and ambient conditions. Thus, our characterization here (and in Ref. 37) is an important initial quantitative step toward comprehensive understanding of CaM signaling in cardiac myocytes.

BsCaM Signal Amplitude May Differ Locally—The amplitude of the global BsCaM-45 signals was smaller than those of BsCaM-2 (Fig. 3H). Although the smaller BsCaM-45 signal is not surprising because of the affinity difference, it may reflect a fundamental difference in the way that lower affinity CaM targets (like CaMKII) are activated by Ca. That is, these low affinity Ca2+-CaM targets may only be activated in restricted compartments where local [Ca2+]i is especially high during excitation-contraction coupling (as in the cleft and subsarcolemmal region near ryanodine receptor and L-type Ca2+ channels). The fact that only a minor fraction of total cellular BsCaM-45 sensor (or CaMKII) is likely to reside at the cleft or subsarcolemmal region (even if concentrated there) would be consistent with the smaller global BsCaM-45 signal amplitude in both experiments and model. Further experiments aimed at testing the model predictions for the cleft and subsarcolemmal domains would require biosensors like BsCaM-45 to be more appropriately localized and to function more like endogenous CaM targets (e.g. CaMKII).

We further speculate that our inability to detect BsCaM-45 transients without overexpression of CaM is not because signals do not occur but because they may be restricted to sensor in the cleft or subsarcolemmal (<1% of cell volume). Because this represents a small fraction of the sensor in the cell, the signals may remain below our detection sensitivity. When we overexpress CaM, this may disproportionately raise free [CaM] and increase the sensor activation level in the bulk cytosol. This increases signal amplitude to detectable levels but may artificially enhance the cytosolic signal. Clarification of this could come from the same sort of targeted sensor studies suggested above.

Limitations—Our dynamic FRET-based Ca2+-CaM measurements in intact ventricular myocytes uncovered differential signal integration of CaM targets because of Ca2+-CaM affinity. Furthermore, mechanistic computational modeling of the activation of these CaM targets reveals that the kinetic differences and diastolic integration of BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 myocyte responses can be quantitatively explained by their known differences in biochemistry. These models help us identify not only what can be currently explained but also where there are limitations or gaps in our understanding. One such aspect is the difference in expected signal amplitude between model and experiments, which may be explained by altered CaM availability and important local CaM signaling (as above). With respect to CaM co-expression, our models indicate that the results are qualitatively similar in terms of kinetics regardless of CaM co-expression. Another issue is the diverse localization of endogenous CaM targets. Although our biosensors are relatively enriched at the T-tubule/Z-line (i.e. the dyadic cleft localization), the dynamic Ca2+-CaM signals are detected globally from the whole cell. Comparison of the amplitudes of the Ca2+-CaM signals in experiments versus simulations suggests that there is likely a combination of cytosolic, subsarcolemmal, and dyadic cleft, which add up to produce the cellular signals. These results point the way for new experimental studies to assess local Ca2+-CaM signals (e.g. with subcellular site specific targeting biosensors or imaging) and also with assessment of downstream CaM target activation (e.g. phosphorylation level of CaMKII and CaN targets). Although the BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45 reporters used here do not share all of the properties of endogenous CaM targets like CaMKII and CaN, FRET biosensors of both CaN activity (52) and CaMKII activity (53) have recently been developed. Future iterations of these biosensors may have sufficient responsiveness for local Ca2+-CaM studies with endogenous CaM targets.

In conclusion, we found that BsCaM-2 and BsCaM-45, two sensors mimicking the Ca2+-CaM binding at the high versus low affinity CaM targets, are both capable of tracking the beat-to-beat intracellular Ca2+ changes, but they respond to the same Ca2+ signal in different ways. In particular, the BsCaM-2 (whose Ca2+-CaM affinity is similar to those of the high affinity CaM targets including CaN) integrates rhythmic Ca2+ signals, whereas the BsCaM-45 (whose Ca2+-CaM affinity is similar to those of the low affinity CaM targets like CaMKII) turns on and off more completely at each heartbeat. These results suggest that various CaM targets (e.g. CaN versus CaMKII) may be differentially regulated during the heart-beat via integration, thereby shaping subsequent cellular processes in the heart. Because both diastolic Ca2+ and heart rate can be changed in the disease state of the heart, this mechanism can differentially tune the downstream CaM-CaM target signaling with pathophysiologic significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anthony Persechini (Division of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, University of Missouri-Kansas City) for the generous gift of the biosensor constructs and Dr. Tao Guo for assistance with the CaM titration experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL30077 and HL80101 (to D. M. B.). This work was also supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (to Q. S.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental data.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: CaM, calmodulin; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; CaMKII, CaM-dependent protein kinase II; CaN, calcineurin; Ca2+-bound CaM, Ca2+-CaM; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; HEK, human embryonic kidney; Iso, isoproterenol; F-CaM, fluorescent CaM.

References

- 1.Clapham, D. E. (2007) Cell 131 1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bers, D. M. (2008) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 70 23–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin, D., and Means, A. R. (2000) Trends Cell Biol. 10 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klee, C. B. (1988) Interaction of Calmodulin with Ca2+and Target Proteins, Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- 5.Pitt, G. S. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73 641–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi, N., Xu, L., Pasek, D. A., Evans, K. E., and Meissner, G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 23480–23486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuhlke, R. D., Pitt, G. S., Deisseroth, K., Tsien, R. W., and Reuter, H. (1999) Nature 399 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier, L. S., and Bers, D. M. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73 631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney, H. L., Bowman, B. F., and Stull, J. T. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 264 C1085–C1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spratt, D. E., Taiakina, V., Palmer, M., and Guillemette, J. G. (2007) Biochemistry 46 8288–8300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vega, R. B., Bassel-Duby, R., and Olson, E. N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 36981–36984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu, Y., Colbran, R. J., and Anderson, M. E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 2877–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vila-Petroff, M., Salas, M. A., Said, M., Valverde, C. A., Sapia, L., Portiansky, E., Hajjar, R. J., Kranias, E. G., Mundina-Weilenmann, C., and Mattiazzi, A. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73 689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu, W., Woo, A. Y., Yang, D., Cheng, H., Crow, M. T., and Xiao, R. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 10833–10839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu, X., and Bers, D. M. (2007) Cell Calcium 41 353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tansey, M. G., Luby-Phelps, K., Kamm, K. E., and Stull, J. T. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 9912–9920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubbard, M. J., and Klee, C. B. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262 15062–15070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis, B. A., Schwartz, A., Samaha, F. J., and Kranias, E. G. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258 13587–13591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolmetsch, R. E., Lewis, R. S., Goodnow, C. C., and Healy, J. I. (1997) Nature 386 855–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCullagh, K. J., Calabria, E., Pallafacchina, G., Ciciliot, S., Serrano, A. L., Argentini, C., Kalhovde, J. M., Lomo, T., and Schiaffino, S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 10590–10595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Koninck, P., and Schulman, H. (1998) Science 279 227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colbran, R. J., and Brown, A. M. (2004) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanhueza, M., McIntyre, C. C., and Lisman, J. E. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 5190–5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chin, E. R. (2005) J. Appl. Physiol. 99 414–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persechini, A., and Cronk, B. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 6827–6830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romoser, V. A., Hinkle, P. M., and Persechini, A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 13270–13274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teruel, M. N., Chen, W., Persechini, A., and Meyer, T. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10 86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran, Q. K., Black, D. J., and Persechini, A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 24247–24250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran, Q. K., Black, D. J., and Persechini, A. (2005) Cell Calcium 37 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maier, L. S., Ziolo, M. T., Bossuyt, J., Persechini, A., Mestril, R., and Bers, D. M. (2006) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 41 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassani, J. W., Bassani, R. A., and Bers, D. M. (1995) Biophys. J. 68 1453–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lippincott-Schwartz, J., Snapp, E., and Kenworthy, A. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2 444–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biermann, M., Rubart, M., Moreno, A., Wu, J., Josiah-Durant, A., and Zipes, D. P. (1998) J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 9 1348–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryder, J. W., Lau, K. S., Kamm, K. E., and Stull, J. T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 20447–20454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakatta, E. G. (2004) Cell Calcium 35 629–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon, T. R., Wang, F., Puglisi, J., Weber, C., and Bers, D. M. (2004) Biophys. J. 87 3351–3371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saucerman, J. J., and Bers, D. M. (2008) Biophys. J., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Johnson, J. D., Snyder, C., Walsh, M., and Flynn, M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peersen, O. B., Madsen, T. S., and Falke, J. J. (1997) Protein Sci. 6 794–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaertner, T. R., Putkey, J. A., and Waxham, M. N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 39374–39382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quintana, A. R., Wang, D., Forbes, J. E., and Waxham, M. N. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334 674–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka, H., Sekine, T., Kawanishi, T., Nakamura, R., and Shigenobu, K. (1998) J. Physiol. 508 145–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bers, D. M. (2006) Physiol. (Bethesda) 21 380–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang, J., Shelton, J. M., Richardson, J. A., Kamm, K. E., and Stull, J. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 19748–19756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, X., Zhang, T., Bossuyt, J., Li, X., McKinsey, T. A., Dedman, J. R., Olson, E. N., Chen, J., Brown, J. H., and Bers, D. M. (2006) J. Clin. Investig. 116 675–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeSantiago, J., Maier, L. S., and Bers, D. M. (2002) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 34 975–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Picht, E., DeSantiago, J., Huke, S., Kaetzel, M. A., Dedman, J. R., and Bers, D. M. (2007) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 42 196–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huke, S., and Bers, D. M. (2007) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 42 590–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattiazzi, A., Vittone, L., and Mundina-Weilenmann, C. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73 648–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ai, X., Curran, J. W., Shannon, T. R., Bers, D. M., and Pogwizd, S. M. (2005) Circ. Res. 97 1314–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, T., Maier, L. S., Dalton, N. D., Miyamoto, S., Ross, J., Jr., Bers, D. M., and Brown, J. H. (2003) Circ. Res. 92 912–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman, R. H., and Zhang, J. (2008) Mol. Biosyst. 4 496–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piljic, A., and Schultz, C. (2008) ACS Chem. Biol. 3 156–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.