Abstract

To test the hypothesis that the bradykinin receptor 2 (BDKRB2) BE1 +9/−9 polymorphism affects vascular responses to bradykinin, we measured the effect of intra-arterial bradykinin on forearm blood flow and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) release in 89 normotensive, nonsmoking, white American subjects in whom degradation of bradykinin was blocked by enalaprilat. BE1 genotype frequencies were +9/+9:+9/−9:−9/−9=19:42:28. BE1 genotype was associated with systolic blood pressure (121.4±2.8, 113.8±1.8, and 110.6±1.8 mm Hg in +9/+9, +9/−9, and −9/−9 groups, respectively; P=0.007). In the absence of enalaprilat, bradykinin-stimulated forearm blood flow, forearm vascular resistance, and net t-PA release were similar among genotype groups. Enalaprilat increased basal forearm blood flow (P=0.002) and decreased basal forearm vascular resistance (P=0.01) without affecting blood pressure. Enalaprilat enhanced the effect of bradykinin on forearm blood flow, forearm vascular resistance, and t-PA release (all P<0.001). During enalaprilat, forearm blood flow was significantly lower and forearm vascular resistance was higher in response to bradykinin in the +9/+9 compared with +9/−9 and −9/−9 genotype groups (P=0.04 for both). t-PA release tended to be decreased in response to bradykinin in the +9/+9 group (P=0.08). When analyzed separately by gender, BE1 genotype was associated with bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–treated men but not women (P=0.02 and P=0.77, respectively), after controlling for body mass index. There was no effect of BE1 genotype on responses to the bradykinin type 2 receptor–independent vasodilator methacholine during enalaprilat. In conclusion, the BDKRB2 BE1 polymorphism influences bradykinin type 2 receptor–mediated vasodilation during angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition.

Keywords: bradykinin, genotype, vasodilation, angiotensin-converting enzyme, plasminogen activators

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and death attributed to acute atherothrombotic events, including myocardial infarction and stroke.1-3 Beneficial properties of ACE inhibitors on cardiovascular disease include improvements in endothelial function, particularly endothelium-dependent vasodilator and fibrinolytic function.4-8 Studies using bradykinin type 2 (B2) receptor antagonists indicate that endogenous bradykinin contributes to the beneficial effects of ACE inhibition on vasodilation and blood pressure,9,10 as well as on endothelial tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) release.11 The underlying mechanisms by which inhibition of ACE contributes to enhanced bradykinin-stimulated vasodilation and t-PA release have not been completely elucidated but include reduced degradation of endogenous bradykinin and enhanced sensitivity of the B2 receptor.12,13

Given that bradykinin contributes to the salutary effects of ACE inhibitors on vascular function via the B2 receptor, genetic factors that affect B2 receptor sensitivity could impact on responses to ACE inhibitors in vivo. Studies have identified a common variant in the B2 receptor gene (BDKRB2)in which the presence (+9) or absence (−9) of a 9-bp repeat sequence in the noncoding exon 1 (BE1) affects the transcription of the B2 receptor.14 The +9 allele has been associated with decreased B2 receptor gene transcription15 and mRNA expression16 compared with the BE1 −9 allele in vitro. Furthermore, the BE1 +9/+9 genotype has been associated with significantly higher coronary risk attributable to hypertension as compared with other BE1 genotype groups17 and with reduced regression of left ventricular mass in response to antihypertensive treatment.18 Moreover, Brull et al19 reported an interaction between the ACE I/D and BE1 +9/−9 polymorphisms on left ventricular growth response to exercise training, such that ventricular hypertrophy was greatest among those with the ACE DD (high ACE activity) and BE1 +9/+9 (low receptor expression) genotypes.

We recently reported that the BE1 +9/+9 genotype was associated with higher forearm vascular resistance (FVR) in normotensive black Americans and with higher systolic blood pressure (SBP) in normotensive white Americans.20 BE1 genotype did not influence the vasodilator response to exogenous bradykinin. However, rapid degradation of bradykinin by ACE could have obscured differences in B2 receptor sensitivity among genotype groups. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that BDKRB2 BE1 genotype affects bradykinin-stimulated vasodilation and t-PA release in the human forearm during ACE inhibition.

Methods

Subjects

Eighty-nine nonobese white American adults (48 males and 41 females) were studied. All of the subjects provided written informed consent. Subjects with a significant cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, endocrine, or hematologic disease were excluded by history, physical examination, laboratory screening, and ECG. None of the subjects smoked or were taking medications. Subjects with fasting cholesterol >5.7 mmol/L (220 mg/dL) were excluded. Pregnancy was excluded in women of childbearing potential by measurement of urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin. The protocol was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental Protocol

Studies were performed in the morning, in a temperature-controlled room. Subjects were studied in the supine position and in the fasting state. A 20-gauge polyurethane catheter (Cook, Inc) was inserted into the brachial artery of the nondominant arm, and an intravenous catheter was placed in the antecubital vein. Arterial catheter patency was maintained by infusion of 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 1 mL/min, and subjects were allowed to rest for 30 minutes before baseline measurements were made and between drug infusions. Heart rate and blood pressure (GE Medical Systems) were continuously monitored throughout the infusion protocol. Forearm blood flow (FBF) was measured using strain-gauge venous occlusion plethysmography (D.E. Hokanson, Bellevue, Wash), as described previously.11,21 FBF was measured at baseline and in response to incremental doses of bradykinin (Clinalfa AG, Läufelfingen, Switzerland), methacholine (Pharmaceutical Compounding Center, Nashville, Tenn), and sodium nitroprusside (Gensia Siccor Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, Calif). The 2 latter drugs were used as B2 receptor–independent controls to rule out a B2 receptor–independent effect of bradykinin on vasodilation and t-PA release. Subjects were given bradykinin at 100, 200, and 400 ng/min; methacholine at 3.2, 6.4, and 12.8 μg/min; and sodium nitroprusside at 1.6, 3.2, and 6.4 μg/min. To avoid an order effect, the sequence of drug administration was randomized. Each drug dose was infused for 5 minutes, and FBF was measured during the last 2 minutes of each drug infusion protocol. FBF is presented as milliliters per 100 milliliters of volume of tissue per minute.

After measurement of FBF, arterial and venous samples were collected simultaneously from the experimental arm at baseline and at the end of each drug dose. Plasma samples for measurement of t-PA and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 antigen were collected in tubes containing 0.105 mol/L of acidified sodium citrate and stored at −70°C until the time of assay. Plasma t-PA and PAI-1 antigen concentrations were determined using a 2-site ELISA (Biopool AB). Net endothelial release of t-PA and PAI-1 antigens in response to bradykinin and methacholine was calculated using the following equation:

where Cv and Ca represent the plasma concentration in the vein and artery, respectively, and forearm plasma flow was calculated from the FBF and hematocrit corrected for 1% trapped plasma. Hematocrit was measured in triplicate using the standard microhematocrit technique and corrected for trapped plasma volume within the trapped erythrocytes.22

To assess the influence of ACE inhibition on the forearm vascular responses to bradykinin and methacholine among the BE1 genotype groups, a continuous intra-arterial infusion of enalaprilat (Ben Venue Laboratories, Inc) was administered at 0.33 μg/min per 100 mL of forearm volume. Measurement of FBF and net release rates of t-PA antigen during bradykinin and methacholine were repeated in the presence of enalaprilat. To prevent arm swelling, the doses of bradykinin were reduced to 25, 50, and 100 ng/min during enalaprilat infusion.

Genotyping

BE1 +9/−9 genotype was determined using PCR amplification, followed by DNA sequencing. The forward 5′-AACGCCCACTGTTTACATCC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACGACCACAGGGAAACTTCT-3′ primers were designed to encompass the polymorphic promoter region, containing the noncoding exon 1 of the BDKRB2 gene. PCR was performed in a final reaction volume of 25 μL containing 80 ng of genomic DNA, 0.2 μmol/L of each oligonucleotide primer, 100 μmol/L of deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and 0.3 U of TaqDNA polymerase (Roche). The thermocycling procedure (Applied Biosystems) consisted of 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 58°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C, followed by final extension for 5 minutes at 72°C. PCR samples were sequenced at the Vanderbilt DNA Sequencing Facility using BigDye Terminator chemistry and resolved on the ABI 7900 automated sequencer platform (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics among groups were determined using 1-way ANOVA or Student t test where appropriate. Differences in responses to the vasoactive agents were determined using general linear model repeated-measures ANOVA in which the within-subject variable was dose and the between-subject variables were genotype group, gender, and/or body mass index. When indicated by a significant F value, Scheffe's test was performed to identify differences between genotype groups. Because we have demonstrated previously that BE1 genotype is associated with SBP in white Americans, FVR was calculated as the ratio of mean arterial pressure:FBF and expressed as arbitrary units (AUs). Data are presented as mean±SEM. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc).

Results

Subject Characteristics

BDKRB2 BE1 genotype distributions were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. Baseline data and data for bradykinin-stimulated vasodilation in the absence of ACE inhibition (Figure 1) for 78 of the 89 subjects were included in an earlier publication.20 There were no differences in age, body mass, body mass index (BMI), diastolic blood pressure, resting FBF and FVR, total cholesterol, plasma t-PA, or PAI-1 antigen among genotype groups. SBP was higher in the +9/+9 group compared with the −9/−9 group (P=0.002) and intermediate in the +9/−9 group (P=0.02 versus +9/+9). Gender distributions were similar in the −9/−9 and +9/−9 groups; however, women were underrepresented in the +9/+9 genotype group (χ2=8.95; P=0.003; 1 degree of freedom).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics of BE1 Genotype Groups

| Variable | −9/−9 (n=28) |

+9/−9 (n=42) |

+9/+9 (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 28.8±1.7 | 31.5±1.9 | 31.1±2.9 |

| Gender, male/female, n | 14/14 | 18/24 | 16/3* |

| Body mass, kg | 73.5±2.5 | 70.6±2.2 | 76.4±2.3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.2±0.5 | 23.9±0.5 | 24.1±0.5 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 110.6±1.8 | 113.8±1.8 | 121.4±2.8† |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 65.9±1.2 | 66.3±1.3 | 69.3±2.2 |

| MAP, mm Hg | 80.9±1.1 | 82.3±1.9 | 85.8±2.1 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.4±0.1 | 4.4±0.1 | 4.6±0.2 |

| FBF, mL/100 mL tissue/min | 4.6±0.5 | 4.4±0.3 | 4.9±0.4 |

| FVR, AU | 22.3±2.0 | 22.5±1.3 | 19.6±1.7 |

| t-PA antigen, ng/mL | 5.6±0.5 | 5.4±0.5 | 5.3±0.7 |

| PAI-1 antigen, ng/mL | 8.8±1.4 | 11.4±1.0 | 7.2±2.2 |

Values are mean±SEM unless otherwise specified. BP indicates blood pressure.

P=0.003 vs +9/−9 and −9/−9 groups.

P=0.007 for effect of genotype by ANOVA, P=0.02 vs −9/+9, and

P=0.002 vs −9/−9 genotype groups for posthoc comparison.

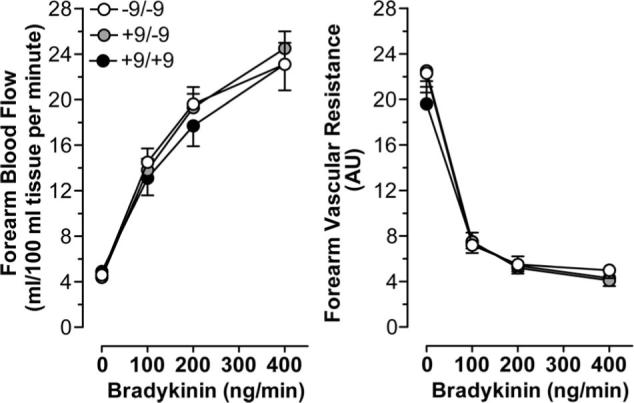

Figure 1.

FBF and FVR responses to bradykinin among BDKRB2 BE1 genotype groups in the absence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Values are means±SEM.

BE1 +9/−9 Genotype and Forearm Vascular Response to Bradykinin in the Absence of ACE Inhibition

Intra-arterial infusion of bradykinin did not affect mean arterial pressure or heart rate. Bradykinin increased FBF and decreased FVR in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). FBF and FVR responses to bradykinin were similar in men and women (maximum FBF: 24.9±1.4 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute in men versus 22.4±1.5 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute in women, P=0.24; minimum FVR: 4.0±0.6 AU in men versus 4.9±0.7 AU in women, P=0.22). FBF and FVR responses to bradykinin were also similar among the BE1 genotype groups in the absence of enalaprilat (P=0.88 and P=0.78, respectively).

BE1 +9/−9 Genotype and Forearm Vascular Response to Bradykinin in the Presence of ACE Inhibition

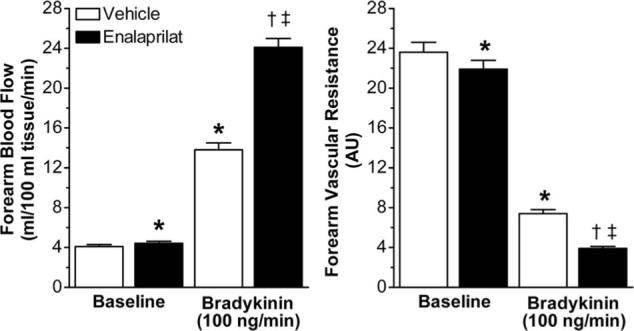

Intra-arterial enalaprilat increased resting FBF (from 4.1±0.2 to 4.4±0.2 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute; P=0.002) and decreased resting FVR (from 23.6±1.0 to 21.9±0.9 AU; P=0.01) but did not affect mean arterial pressure. As illustrated in Figure 2, enalaprilat potentiated the FBF response to bradykinin to 24.1±0.9 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute during enalaprilat versus 13.8±0.7 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute during vehicle at the 100 ng/min dose (P<0.001). The FVR response to bradykinin was also potentiated by enalaprilat (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

FBF and FVR at baseline and during bradykinin (100 ng/min), in the absence and presence of enalaprilat (0.33 μg/min per 100 mL forearm volume). Values are mean±SEM. *P≤0.01 vs baseline vehicle; †P<0.001 vs baseline enalaprilat; ‡P<0.001 vs bradykinin+vehicle.

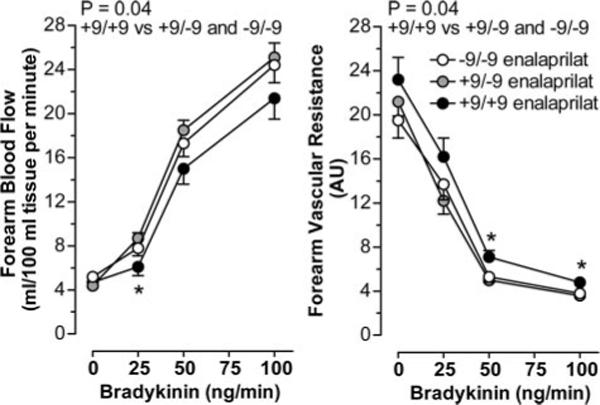

During enalaprilat, the forearm vasodilatory response to intra-arterial bradykinin was related to the BE1 genotype. Thus, in the presence of enalaprilat, FBF was significantly lower and FVR higher during bradykinin in the +9/+9 group compared with the +9/−9 and −9/−9 genotype groups combined (P=0.04 for both; Figure 3). During enalaprilat, BMI significantly affected FBF responses to bradykinin (P=0.005). As in the absence of enalaprilat, there was no effect of gender on bradykinin-stimulated FBF, and adjustment for gender and BMI did not alter the significance of the effect of genotype (P=0.03).

Figure 3.

FBF and FVR responses to bradykinin among BDKRB2 BE1 genotype groups in the presence of enalaprilat. Values are mean±SEM. *P<0.05 for BE1 +9/+9vs +9/−9 and −9/−9.

BE1 +9/−9 Genotype and Endothelial t-PA Antigen Release

Basal endothelial t-PA antigen release was similar among the genotype groups (P=0.46). Bradykinin increased t-PA antigen release across the forearm in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.001). In the absence of enalaprilat, the capacity of the endothelium to release t-PA in response to bradykinin was similar among genotype groups (P=0.64). For example, at the highest dose of bradykinin (400 ng/min), net release rates of t-PA antigen were similar in the −9/−9 (from 0.2±0.8 to 58.8±10.1 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute), +9/−9 (from −0.2±0.5 to 60.8±9.5 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute), and +9/+9 (from 1.3±1.5 to 72.6±9.7 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute) groups.

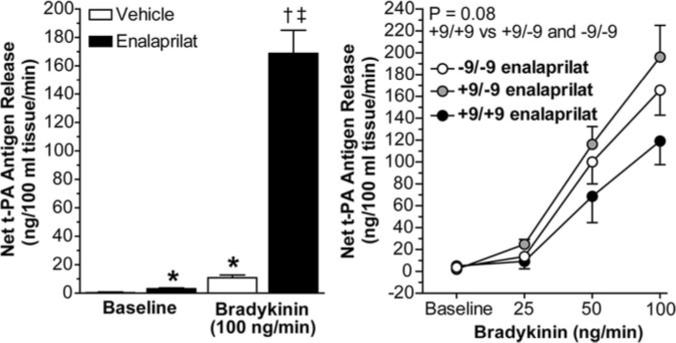

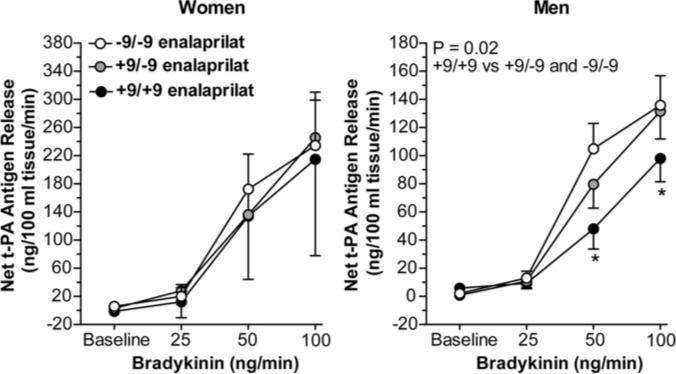

Intra-arterial administration of enalaprilat increased basal release of t-PA antigen (P<0.001) without affecting basal release of PA1−1 antigen and potentiated the response to exogenous bradykinin (P<0.001; Figure 4). During enalaprilat, the t-PA response to bradykinin tended to be blunted (≈55%; P=0.08) in the +9/+9 group (from 5.0±1.7 to 119.1±21.5 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute) compared with the +9/−9 (from 2.0±0.8 to 196.0±29.0 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute) and −9/−9 (from 3.7±1.2 to 165.7±23.0 ng/100 mL of tissue per minute) genotype groups combined. Gender affected bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in the presence of ACE inhibition (P<0.001). Endothelial t-PA release was 83% higher in women compared with men. After controlling for gender, an effect of BE1 genotype was no longer evident in the overall group. When analyzed separately in men and women, however, BE1 genotype tended to influence the t-PA response to bradykinin during enalaprilat in men such that t-PA release tended to be lower in the +9/+9 group compared with the +9/−9 and −9/−9 geno-type groups combined (P=0.05 for dose × BE1 genotype interaction). When BMI was included in the analysis, net t-PA release in response to bradykinin was significantly decreased in +9/+9 men compared with +9/−9or −9/−9 men (P=0.02 for effect of genotype; Figure 5). In contrast, there was no effect of BE1 genotype on the t-PA response to bradykinin in the presence of ACE inhibition in women, even after controlling for BMI (P=0.77; Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Left, Net release rate of t-PA antigen at baseline and during bradykinin (100 ng/min), in the absence and presence of enalaprilat (0.33 μg/min per 100 mL forearm volume). *P<0.001 vs baseline vehicle; †P<0.001 vs baseline enalaprilat; ‡P<0.001 vs bradykinin+vehicle. Values are mean±SEM. Right, Net release rate of t-PA in response to bradykinin in the presence of enalaprilat among BDKRB2 BE1 genotype groups.

Figure 5.

Effect of bradykinin on net release of t-PA antigen during enalaprilat among BDKRB2 BE1 genotype groups, analyzed separately in women and in men. Data presented are estimated marginal means after controlling for quartile of BMI. *P≤0.05 vs −9/−9 and −9/+9.

BE1 +9/−9 Genotype and Responses to Methacholine and Sodium Nitroprusside

There was no effect of BE1 genotype on FBF, FVR, or net release of t-PA antigen in response to the endothelium-dependent, B2 receptor-independent agonist methacholine either in the absence or presence of enalaprilat (Table 2). In addition, there were no significant differences among the −9/−9 (from 4.1±0.3 to 20.9±1.5 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute), +9/−9 (from 4.4±0.3 to 19.6±1.1 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute), and +9/+9 (from 4.4±0.3 to 19.0±1.4 mL/100 mL of tissue per minute) genotype groups in the forearm vasodilator responses to sodium nitroprusside.

Table 2.

Forearm Vascular Responses to Methacholine in the Absence and Presence of ACE Inhibition Among the BE1 Genotype Groups

| Variable |

FBF, mL/100 mL tissue/min |

FVR, AU |

t-PA Antigen Release, ng/100 mL tissue/min |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methacholine Dose (μg/min) | Baseline | 3.2 | 6.4 | 12.8 | Baseline | 3.2 | 6.4 | 12.8 | Baseline | 3.2 | 6.4 | 12.8 |

| Genotype group | ||||||||||||

| −9/−9 vehicle | 4.4±0.4 | 18.4±1.4* | 25.3±1.7* | 34.1±2.3* | 22.5±1.8 | 5.9±0.9* | 3.7±0.3* | 2.8±0.3* | 0.8±0.7 | 10.1±6.2 | 9.1±6.1 | 15.0±10.4 |

| −9/−9 enalaprilat | 4.6±0.4 | 19.2±1.3* | 27.7±1.6* | 34.3±2.1* | 21.0±1.7 | 4.9±0.4* | 3.3±0.2* | 2.7±0.2* | 1.6±0.8 | 4.0±3.8 | 18.8±5.4* | 21.8±6.9* |

| +9/−9 vehicle | 5.3±0.6 | 18.9±1.1* | 34.0±9.1* | 31.9±1.6* | 21.2±1.8 | 5.0±0.3* | 3.7±0.2* | 2.9±0.2* | 0.5±0.7 | 4.2±3.6 | 3.3±4.3 | 33.0±11.3* |

| +9/−9 enalaprilat | 4.7±0.4 | 21.0±1.2* | 27.2±1.6* | 35.2±1.7* | 21.5±1.5 | 4.5±0.3* | 3.6±0.2* | 2.6±0.2* | 1.5±0.8 | 4.5±3.7 | 9.2±4.3 | 14.9±5.9* |

| +9/+9 vehicle | 4.7±0.5 | 17.2±1.3* | 26.2±2.4* | 32.0±3.2* | 21.4±1.5 | 5.8±0.5* | 3.9±0.4* | 3.3±0.4* | 0.8±0.9 | 12.2±6.0 | 2.2±10.0 | 5.1±8.8 |

| +9/+9 enalaprilat | 4.3±0.4 | 20.2±1.7* | 26.6±2.5* | 34.8±3.6* | 23.1±2.0 | 4.8±0.4* | 3.8±0.3* | 2.9±0.2* | 1.5±1.4 | 4.3±6.5 | 6.3±6.4 | 10.5±8.6 |

Values are mean±SEM.

P<0.05 vs baseline.

Discussion

We have reported previously that the BDKRB2 BE1 polymorphism associates with SBP in normotensive white Americans but does not affect the vasodilator response to exogenous bradykinin in the forearm.20 Here we report the effect of intra-arterial bradykinin infusion during administration of the ACE inhibitor enalaprilat. As expected,11,23 ACE inhibition potentiated the effect of bradykinin on FBF and t-PA release. More importantly, BDKRB2 BE1 genotype influenced bradykinin-stimulated vasodilation and tended to influence t-PA release during ACE inhibition, such that individuals homozygous for the BE1 +9 allele exhibited blunted responses to bradykinin compared with carriers of a −9 allele. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address the effect of variation at the BDKRB2 gene on the vascular effects of bradykinin during ACE inhibition in humans. Moreover, there was no effect of BDKRB2 BE1 genotype on nitroprusside-stimulated vasodilation or methacholine-stimulated vasodilation or t-PA release, either in the absence or presence of ACE inhibition, suggesting that the BE1 genotype specifically affected B2 receptor sensitivity.

We have reported previously that, during ACE inhibition, bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release is enhanced in women compared with men, whereas there is no effect of gender on bradykinin-stimulated vasodilation.11 In the current study we also observed an interactive effect of the BKDRB2 BE1 +9/−9 polymorphism and gender on bradykinin-mediated t-PA release, such that the BE1 +9/+9 genotype was associated with decreased t-PA release in men but not in women. The mechanism of this gender effect requires further exploration. One nonrandomized study of hormone therapy suggests that estrogen affects bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release24; however, endogenous and bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release are also increased in ACE inhibitor–treated postmenopausal women compared with age-matched men, suggesting an estrogen-independent effect of gender.25 In this regard, decreased bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in men during ACE inhibition may reflect an effect of testosterone to decrease bradykinin-stimulated calcium influx.26

Two potential limitations merit discussion. First, in an effort to minimize variability in the present study, we included white, healthy, nonsmoking adults of similar age who were not taking medications. We have reported previously that ethnicity influences the effect of the BDKRB2 BE1 genotype on resting vascular function, such that the BE1 +9/+9 genotype is associated with increased SBP in normotensive white Americans and with increased FVR in normotensive black Americans.20 In addition, ethnicity has been shown to influence the cardioprotective effects of ACE inhibitors.27 For this reason, the findings of the present study are not necessarily generalizable to other ethnic groups.

In addition, by chance, men were overrepresented in the BE1 +9/+9 genotype group. Because there was no effect of gender on the vasodilator response to bradykinin, either in the presence or absence of enalaprilat, this is unlikely to have impacted the relationship between BDKRB2 BE1 genotype and the vasodilator response to bradykinin during ACE inhibition. Indeed, adjusting for gender did not alter the results. Gender did, however, influence bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release. We, therefore, conducted separate analyses of the effect of BE1 genotype on bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in men and women. The observation that BE1 genotype did not affect bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in women but that t-PA release was 2-fold greater in women compared with men, regardless of genotype, suggests that increased endothelial storage of t-PA trumps genetic variability at the B2 receptor in determining bradykinin-stimulated t-PA release in women.

Perspectives

ACE inhibitors reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and death attributed to acute atherothrombotic events, including myocardial infarction and stroke.1-3 Bradykinin contributes to vasodilation and endogenous t-PA release during ACE inhibition via its B2 receptor.11 This study provides the first evidence that the BE1 +9/−9 polymorphism influences bradykinin-mediated vasodilation, as well as bradykinin-mediated t-PA release in men, during ACE inhibition. Preventing the degradation of bradykinin by ACE unmasked the association between the bradykinin B2 receptor BE1 genotype and responses to bradykinin.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rhoda Jones for technical assistance and Tami Neal, RN, and Delia Woods, RN, for their nursing assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants HL065193, HL060906, HL085740, and M01RR000095. G.P.V.G. and J.M.L. were supported by Clinical Pharmacology Training Grant T32 GM97569. J.B.B. was supported by HL076133.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study investigators Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet. 1993;342:821–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Jr, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. The SAVE investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs I, Toth J, Tarjan J, Koller A. Correlation of flow mediated dilation with inflammatory markers in patients with impaired cardiac function. Beneficial effects of inhibition of ACE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura M, Funakoshi T, Arakawa N, Yoshida H, Makita S, Hiramori K. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on endothelium-dependent peripheral vasodilation in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pretorius M, Murphey LJ, McFarlane JA, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition alters the fibrinolytic response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 2003;108:3079–3083. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105765.54573.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancini GB, Henry GC, Macaya C, O'Neill BJ, Pucillo AL, Carere RG, Wargovich TJ, Mudra H, Luscher TF, Klibaner MI, Haber HE, Uprichard AC, Pepine CJ, Pitt B. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with quinapril improves endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. The Trend (Trial on Reversing Endothelial Dysfunction) study. Circulation. 1996;94:258–265. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan DE, Rouleau JL, Ridker PM, Arnold JM, Menapace FJ, Pfeffer MA. Effects of ramipril on plasma fibrinolytic balance in patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;96:442–447. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gainer JV, Morrow JD, Loveland A, King DJ, Brown NJ. Effect of bradykinin-receptor blockade on the response to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1285–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810293391804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witherow FN, Dawson P, Ludlam CA, Fox KA, Newby DE. Marked bradykinin-induced tissue plasminogen activator release in patients with heart failure maintained on long-term angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:961–966. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pretorius M, Rosenbaum D, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition increases human vascular tissue-type plasminogen activator release through endogenous bradykinin. Circulation. 2003;107:579–585. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046268.59922.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcic B, Deddish PA, Jackman HL, Erdos EG. Enhancement of bradykinin and resensitization of its B2 receptor. Hypertension. 1999;33:835–843. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdos EG. Kinins, the long march–a personal view. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:485–491. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun A, Kammerer S, Maier E, Bohme E, Roscher AA. Polymorphisms in the gene for the human B2-bradykinin receptor. New tools in assessing a genetic risk for bradykinin-associated diseases. Immunopharmacology. 1996;33:32–35. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun A, Maier E, Kammerer S, Muller B, Roscher AA. A novel sequence polymorphism in the promoter region of the human B2-bradykinin receptor gene. Hum Genet. 1996;97:688–689. doi: 10.1007/BF02281884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lung CC, Chan EK, Zuraw BL. Analysis of an exon 1 polymorphism of the B2-bradykinin receptor gene and its transcript in normal subjects and patients with C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:134–146. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhamrait SS, Payne JR, Li P, Jones A, Toor IS, Cooper JA, Hawe E, Palmen JM, Wootton PT, Miller GJ, Humphries SE, Montgomery HE. Variation in bradykinin receptor genes increases the cardiovascular risk associated with hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1672–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallberg P, Lind L, Michaelsson K, Karlsson J, Kurland L, Kahan T, Malmqvist K, Ohman KP, Nystrom F, Melhus H. B2 bradykinin receptor (B2BKR) polymorphism and change in left ventricular mass in response to antihypertensive treatment: Results from the Swedish Irbesartan Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Investigation versus Atenolol (SILVHIA) Trial. J Hypertens. 2003;21:621–624. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200303000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brull D, Dhamrait S, Myerson S, Erdmann J, Woods D, World M, Pennell D, Humphries S, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Montgomery H. Bradykinin B2BKR receptor polymorphism and left-ventricular growth response. Lancet. 2001;358:1155–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pretorius MM, Gainer JV, Van Guilder GP, Coelho EB, Luther JM, Fong P, Rosenbaum DD, Malave HA, Yu C, Ritchie MD, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. The bradykinin type 2 receptor BE1 polymorphism and ethnicity influence systolic blood pressure and vascular resistance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100250. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Guilder GP, Hoetzer GL, Smith DT, Irmiger HM, Greiner JJ, Stauffer BL, DeSouza CA. Endothelial t-PA release is impaired in overweight and obese adults but can be improved with regular aerobic exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E807–E813. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00072.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaplin H, Jr, Mollison PL. Correction for plasma trapped in the red cell column of the hematocrit. Blood. 1952;7:1227–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labinjoh C, Newby DE, Pellegrini MP, Johnston NR, Boon NA, Webb DJ. Potentiation of bradykinin-induced tissue plasminogen activator release by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01562-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoetzer GL, Stauffer BL, Irmiger HM, Ng M, Smith DT, DeSouza CA. Acute and chronic effects of oestrogen on endothelial tissue-type plasminogen activator release in postmenopausal women. J Physiol. 2003;551:721–728. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretorius M, Luther JM, Murphey LJ, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition increases basal vascular tissue plasminogen activator release in women but not in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2435–2440. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000186185.13977.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio-Gayosso I, Garcia-Ramirez O, Gutierrez-Serdan R, Guevara-Balcazar G, Munoz-Garcia O, Morato-Cartajena T, Zamora-Garza M, Ceballos-Reyes G. Testosterone inhibits bradykinin-induced intracellular calcium kinetics in rat aortic endothelial cells in culture. Steroids. 2002;67:393–397. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weir MR, Gray JM, Paster R, Saunders E. Differing mechanisms of action of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in black and white hypertensive patients. The trandolapril multicenter study group. Hypertension. 1995;26:124–130. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]