Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is one of these age-old diseases that have been plaguing the health of affected individuals for thousands of years. It was not until two decades ago that scientists have first got a peek on the molecular basis of the disease and uncovered the genetic abnormality. Yet, an effective therapy proves elusive and remains to be developed.

DMD is the most common form of childhood muscular dystrophies. This X-linked recessive disease affects one in every 3,000 live male births. A comprehensive description of the disease was published in 1868 by Guillaume B.A. Duchenne, hence, the eponym Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The symptoms of affected boys are often unnoticeable until they are 2∼5 years old when they have problems in crawling and walking. They begin to show severe muscle wasting and lose their walking ability at around age 10. These boys usually die in their early twenties due to difficulties in breathing and/or heart failure. Damaged skeletal muscle in the diaphragm leads to the breathing problem and damaged cardiac muscle causes heart failure.

The first major victory in the battle against DMD came in late 1980s when Kunkel's group discovered the faulty gene, which they later named the dystrophin gene (Kunkel, 2005). In the gene's name, “dystroph” because it was isolated from patients with muscular dystrophy and “in” because names of most muscle proteins are ended with “in” (Kunkel, 2005). The 2.5 megabase dystrophin gene is one of the largest in our genome. It is located on the X-chromosome and encodes a 427 kilodalton protein, also a very large protein.

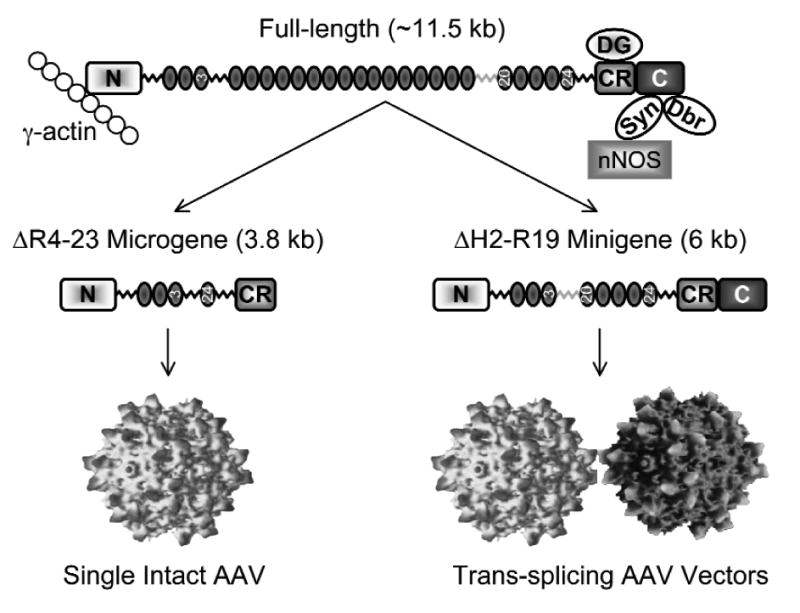

The dystrophin protein is composed of four units: the head, the body, the cysteine-rich domain, and the tail (Figure 1). The head of the protein (N-terminus) interacts with filamentous γ-actin, an important cytoskeleton protein. The vast majority of the dystrophin protein is made of a long rod-shaped body (also called the rod domain) consisting of 24 spectrin-like repeats and four hinges. Immediately following the body is the cysteine-rich domain which links dystrophin to dystroglycan, a transmembrane protein that interacts with the extracellular matrix. Essentially, dystrophin and dystroglycan form a bridge that connects cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix. The partnership among dystrophin, dystroglycan, and the extracellular matrix is further enforced by a group of small transmembrane proteins called sarcoglycans. During muscle contraction and relaxation, the change in muscle shape creates a shearing force on the sarcolemma (muscle cell membrane). The dystrophin/dystroglycan bridge protects the sarcolemma from tearing damage and therefore maintains the structural integrity of muscle cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic outline of the dystrophin protein and the strategies to deliver the micro- and mini-dystrophin genes by AAV. The N-terminus (N) of the dystrophin protein interacts with γ-actin. The body of the dystrophin body is consisted of 24 spectrin-like repeats and four hinges. Repeats 3, 20, and 24 are marked with numerical numbers. Hinge 3 (gray color) is different from other hinges and it contains a viral protease site. The cysteine-rich (CR) domain interacts with dystroglycan (DG). The C-terminus (C) of the dystrophin protein interacts with syntrophin (Syn) and dystrobrevin (Dbr). Syntrophin recruits nNOS to the sarcolemma. The 3.8 kb microgene is missing the regions from repeat 4 to repeat 23 as well as the C-terminal domain. This microgene can be delivered by a single intact AAV virion. The 6 kb minigene has a smaller deletion (from hinge 2 to repeat 19). The minigene can be efficiently expressed by the trans-splicing AAV vectors.

At the tail end of the dystrophin protein is the C-terminus. Instead of participating directly in the physical link between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton, the C-terminus recruits a unique set of cytosolic proteins to the site of sarcolemma. These include dystrobrevin, syntrophin, and indirectly, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). The biological significance of this cytosolic protein complex remains to be fully appreciated but it is thought to at least contribute to the signaling transduction process in muscle cells. Furthermore, nitric oxide generated by nNOS reduces vasoconstriction in contracting muscle and facilitates blood perfusion during exercise. Collectively, dystrophin orchestrates its interacting proteins into a functional complex known as dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex or DGC. In DMD, the loss of dystrophin results in the collapse of the DGC and eventually muscle cell death.

The discovery of the dystrophin gene has raised the hope of curing this devastating disease by gene therapy. The goal is to re-express the lost dystrophin protein in muscle cells. This can be achieved either by introducing to muscle cells a new copy of a functional dystrophin gene or by repairing the mutated gene. Irrespective of the approach, a key issue is to have an effective method to deliver the therapeutic gene to muscle cells. Many viral and nonviral vectors have been evaluated for muscle cell gene transfer. The champion goes to adeno-associated virus (AAV), considered the most powerful and the least toxic viral vector.

AAV is the smallest DNA virus with an average size of 20 nm. AAV was discovered in 1965 as a defective contaminating virus in an adenovirus stock (Atchison et al., 1965). Wild-type AAV has a 4.8 kilobase (kb) genome, and in a recombinant AAV vector a therapeutic gene expression cassette of up to 5 kb can be efficiently packaged. This is apparently not enough for the full-length dystrophin gene. How can we take advantage of the efficient muscle transduction property of AAV and use this smallest virus to deliver the largest gene?

Theoretically, this can be achieved by either shrinking the size of the dystrophin gene and/or enlarging the packaging capacity of the AAV vector. If we strip off all the non-coding parts of the dystrophin gene, we will end up with a ∼11.5 kb cDNA that can be translated into the full-length protein. Any further truncation will endanger the completeness of the protein itself. The whole question now boils down to what we can do without. As it often happens, nature has its way of divulging its secret. A breakthrough came when Davies and her colleagues examined the dystrophin gene in a patient with a very mild version of the disease in 1990 (England et al., 1990). Unlike the rest of the patients, this patient in Davies's study was still able to walk at age 60. Detailed genetic examination showed that the patient had a large deletion in the middle of the dystrophin gene. Instead of the full-length protein, this patient had a smaller mini-protein about 54% the size of the full-length protein. Out of 24 spectrin-like repeats and four hinges of the rod-domain, 15 and a half repeats and one hinge were missing in the mini-dystrophin protein in this patient. Further manipulation of this mini-protein by Chamberlain and colleagues resulted in a 6 kb minigene that is as functional as the full-length gene in a mouse model of DMD (Harper et al., 2002). These results suggest that a smaller rod domain is sufficient to protect muscle.

“Collectively, dystrophin orchestrates its interacting proteins into a functional complex known as dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex or DGC. In DMD, the loss of dystrophin results in the collapse of the DGC and eventually muscle cell death.”

Although promising, the mini-dystrophin gene is still too large for the AAV vector. What else can we take out from the full-length gene without inactivating the entire protein? Obviously the parts that are involved in connecting cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix are essential to maintaining the physical link and buffering the stress during muscle contraction. These parts include the actin-binding domain and the cysteine-rich domain. Removing the C-terminal domain, on the other hand, results in a tail-less dystrophin that seems to have minimal effect on muscle function in mice. Based on these findings, several laboratories generated the massively truncated micro-dystrophin genes by deleting parts of the rod domain and the C-terminal tail (Harper, et al., 2002). Although the microgene was not as competent as the minigene, it was able to protect dystrophic mice from contraction-induced injury. Furthermore, it reduced muscle fibrosis and inflammation and extended the life span of dystrophic mice (Gregorevic et al., 2006; Yue et al., 2006).

In the field of experimental medicine, the results obtained in animal studies do not always pan out in human patients. Whether the therapeutic magic of the microgene will reproduce itself in human patients remains to be tested. One important concern is the lack of the C-terminal tail in the microgene. It is possible that mouse studies are not sensitive enough to reveal the functional importance of this region in human muscle. In clinics, there do exist DMD patients whose only mutation is located at the C-terminus.

Comparing with the microgene, the future of the mini-dystrophin gene is much brighter. First, it contains all four units of the full-length protein. Second, it comes from human and we already know it works in human. Third, unlike the microgene, the minigene is fully competent in mice.

Putting the entire minigene in a single AAV virion is mission impossible. However, a line-up of two virions will add up to a total of 10 kb packaging capacity. This should be sufficient for the 6 kb minigene. One can imagine splitting the minigene into two parts and having them carried by two AAV virions. The question is how to reconstitute the original gene after the gene fragments are delivered into muscle cells. There are several critical considerations. First, the refurbished gene should be organized in the right order, meaning the head in front of the tail. Second, the protein coding sequence should be faithfully maintained. Third, each piece of the fragmented gene should not yield protein products. If partial proteins are expressed, they can act as new antigens and induce unwanted immune responses, and they can compete with the therapeutic protein for interacting sites with γ-actin and dystroglycan. Fourth, the reconstitution efficiency should be high enough to meet the therapeutic need. Among these issues, the third one is the easiest to handle. To express a protein, the gene should have a promoter, a polyadenylation signal, and the start and the stop codons. When a gene is split into two parts, none of the fragments will have all four components, therefore minimizing the risk of partial protein expression.

Creative means are needed to solve other issues. Luckily, nature has done its homework for us. If two genes share an identical region, they will likely recombine through a process called homologous recombination. Based on this knowledge, we and other investigators have developed a dual vector approach called the overlapping AAV vectors. In this approach, the first two-third of the gene is packaged in one AAV virion and the second two-third of the gene is packaged in another AAV virion. So, the vector genome in one virus overlaps with that in the other virus. The middle third of the gene is shared by both viruses. When these two viruses meet inside a cell, the shared region will recombine through homologous recombination and restore the full-length gene. When this overlapping approach was tested, it worked extremely well for certain genes such as the alkaline phosphatase gene. Unfortunately, it did not work for other genes such as the β-galactosidase gene and the mini-dystrophin gene. Since homologous recombination is a DNA sequence-dependent process, it is very likely that certain sequences are more prone to recombination than others.

Are there other ways to bring two AAV genomes together? At the ends of the AAV genome, there is a structure called the inverted terminal repeat (ITR). The ITR acts as a packaging signal during AAV production. Interestingly, once inside cell, the ITR directs a head-to-tail recombination between two AAV genomes. Basically, the tail-end ITR of one AAV genome will recombine with the head-end ITR of another AAV genome. Thus two AAV genomes are connected. If we can remove the ITR junction, we will then be able to reconstitute a full-length gene that has been split and packaged in two AAV viruses. To solve this problem, we need to re-visit the basic molecular biology. Our gene is consisted of two elements, exons and introns. Exons are transcribed into messenger RNA for protein expression. Introns are removed through a process called splicing. If we engineer a splicing donor signal at the tail-end ITR of one AAV genome and a splicing acceptor signal at the head-end ITR of another AAV genome, we should then be able to splice out the ITR junction that is created when the two gene segments are linked. Based on this knowledge, we and other investigators developed another dual vector approach called the trans-splicing approach.

In the trans-splicing approach, we have two AAV vectors to carry a large gene. The head portion of the gene is carried by a vector called AV.Donor. This vector also carries the splicing donor signal. The tail portion of the gene is carried by a vector called AV.Acceptor and it also carries the splicing acceptor signal. When we deliver both vectors to the same cell, their genomes recombine. The engineered splicing signals will then remove the ITR junction and finally the full-length protein will be expressed (Figure 2). Many groups including ours tested the trans-splicing approach. The conclusion of these studies is that the strategy works but the efficiency is too low to be useful for DMD gene therapy.

Figure 2.

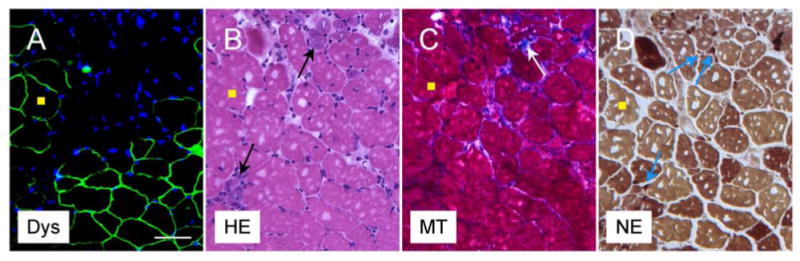

AAV gene therapy reduces dystrophic pathology in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Representative photomicrographs of serial sections of an AAV treated muscle at two months after gene therapy. A, immunostaining for dystrophin (Dys). Dystrophin expression (green) is only seen in AAV infected myofibers. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). B, Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining shows small degenerative myofibers in untreated areas (arrows). The treated muscle is protected from degeneration. C, Masson trichrome (MT) staining illustrates fibrosis (blue) in untreated area (arrow). D, Non-specific esterase (NE) staining reveals macrophage (small dark brown cells) infiltration in untreated areas (arrows). Yellow squares mark the same myofiber in serial sections. Scale bar, 50 μm.

To improve the efficiency of the trans-splicing approach, we have evaluated the potential rate-limiting steps. Our results suggest that rational selection of the gene-splitting site is the key to the success of the trans-splicing approach (Lai et al., 2005). After screening a series of the potential sites in the mini-dystrophin gene, we have identified a perfect site. This site is located at the junction between exons 60 and 61. The trans-splicing vectors based on this site transduced 90% of muscle cells in a mouse model of DMD after local injection of the recombinant viruses (Figure 2). Furthermore, dystrophic pathology was ameliorated and force was improved in treated muscle (Lai, et al., 2005).

“To improve the efficiency of the trans-splicing approach, we have evaluated the potential rate-limiting steps. Our results suggest that rational selection of the gene-splitting site is the key to the success of the trans-splicing approach (Lai et al., 2005). After screening a series of the potential sites in the mini-dystrophin gene, we have identified a perfect site.”

The discovery of the dystrophin gene divides the battle against DMD into pre-molecular and molecular periods. To win the battle, we need to transform our knowledge on the dystrophin gene into an effective therapy. There is no doubt that gene therapy, likely the AAV-mediated gene therapy, will produce the magic. But the road from the smallest viral vector to the largest gene is not without obstacles. We have now reached the critical point of “the proof-of principle” success in the mouse model of DMD. We are quite optimistic that further development of AAV-mediated microgene and/or minigene therapy in large animal models will bring the cure to patients in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The DMD gene therapy research in Duan laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR-49419) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

References and Further Readings

- Atchison RW, Casto BC, Hammon WM. Adenovirus-associated defective virus particles. Science. 1965;149:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3685.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SB, Nicholson LV, Johnson MA, Forrest SM, Love DR, Zubrzycka-Gaarn EE, Bulman DE, Harris JB, Davies KE. Very mild muscular dystrophy associated with the deletion of 46% of dystrophin. Nature. 1990;343:180–182. doi: 10.1038/343180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, Finn E, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Murry CE, Chamberlain JS. rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:787–789. doi: 10.1038/nm1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper SQ, Hauser MA, DelloRusso C, Duan D, Crawford RW, Phelps SF, Harper HA, Robinson AS, Engelhardt JF, Brooks SV, et al. Modular flexibility of dystrophin: implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature Medicine. 2002;8:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel LM. 2004 William Allan Award address. Cloning of the DMD gene. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:205–214. doi: 10.1086/428143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Yue Y, Liu M, Ghosh A, Engelhardt JF, Chamberlain JS, Duan D. Efficient in vivo gene expression by trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;23:1435–1439. doi: 10.1038/nbt1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Liu M, Duan D. C-terminal truncated microdystrophin recruits dystrobrevin and syntrophin to the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex and reduces muscular dystrophy in symptomatic utrophin/dystrophin double knock-out mice. Molecular Therapy. 2006;14:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]