Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) can regulate all elements of the immune system, and therefore are an ideal target for vaccination. During the last two decades, as a result of extensive research, DCs became the primary target of antitumor vaccination as well. A critical issue of antitumor vaccination is the phenotype of the dendritic cell used. It has been recently shown that several nuclear hormone receptors, and amongst them the lipid-activated nuclear receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), have important roles in effecting the immunophenotype of human dendritic cells. It regulates primarily lipid metabolism and via this it influences the immunophenotype of DCs by altering lipid antigen uptake, presentation, and also other immune functions. In this review, we summarize the principles of antitumor vaccination strategies and present our hypothesis on how PPARγ-regulated processes might be involved and could be exploited in the design of vaccination strategies.

1. DENDRITIC CELLS IN TUMORS

Dendritic cells (DCs) were discovered in mouse spleen by Ralph Steinman and Zanvil Cohn in 1973 [1]. Immature dendritic cells (IDCs) are sentinels of the immune system, continuously monitoring peripheral tissues for invaders, capture and process antigens, and migrate to the draining lymph nodes where they present peptides to naive Treg cells (T cells) and activate them [2]. The full activation of T cells requires special peptide-MHCI or peptide-MHCII complexes and additional signals from DCs in the form of various costimulatory molecules and cytokines. Furthermore, activated CD4+ T cells could be polarized to T helper 1 (Th1) and T helper 2 (Th2) subtypes. These processes are dependent on the cytokines interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-4, and IL-10 secreted by mature DCs (MDCs). In response to IL-12, T cells polarize to Th1 and enhance CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell response against tumor cells or pathogens, while IL-4- and IL-10-activated Th2 cells promote humoral immune response and/or tolerance. Another important point is that DCs can induce T-cell tolerance to self-antigens and via this prevent and reduce autoimmune diseases.

Importantly, it appears that tumor tissues have characteristic immune environments with distinct DC subset distributions. Different DC subset localization within the compartments of tumor has been reported in colorectal cancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Dadabayev et al. investigated the infiltration pattern of DCs in human colorectal tumor samples analyzed with S100 and HLA class II DC markers. S100+ and CD1a+ DCs were found in tumor epithelium, in parallel with intraepithelial CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell infiltration and suggested increased disease-free survival, while HLA class II+ cells were observed in the stromal compartment, correlated with adversed outcome of the tumor [3]. Later they utilized CD208 (DC-LAMP) marker for marking MDCs and proved that CD208+ DCs were detectable in the peritumoral area, and infiltration of MDCs into tumor epithelium was correlated also with decreased patient survival [4]. In primary squamous cell carcinoma patients, IDCs and MDCs were characterized with distinct tissue localization patterns. Immature Langerhans cells (LCs) and DC-SIGN+ interstitial DCs were found inside the tumor tissue while the number of mature CD208+ DCs was limited. Moreover, CD123+ plasmacytoid DC representation in the tumor area was correlated with poor survival [5]. Importantly, DCs interact with tumor cells and cytokines produced by tumor cells or immune cells influence DC function and maturation. The tumor microenvironment affects DC differentiation from CD14+ monocytes and haematopoietic precursors promoting an early and dysfunctional maturation of DCs. Several reports described reduced the number of DC in peripherial blood, tumor tissues, and draining lymph nodes in cancer patients. Partial maturation of DCs by tumor-derived factors like IL-10, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and TGF-β induces self-tolarence and promotes conversion of naive T cells to regulator T cells, favoring development of suppressive T cells. Presence of tolerogenic T cells in tumor beds induces local immune suppression and alters the function of anticancer effector T cells. These cells, isolated from draining lymph nodes of patients with pancreas or breast cancer secrete IL-10 and TGF-β, prevent activated CD4+ CD25− and CD8+ effector T cells, and suppress tumor-specific immune response [6]. Apart from the fact that DCs are involved in activation of Treg, there is an increasing amount of evidence about T cells, which can be recruited into tumors and affect DC development. Decreased CD80 and CD86 cell surface markers by T cells lead to reduced T-cell stimulatory ability of DCs [7, 8]. Immunosuppressive B7-3/4 molecules are upregulated on DCs upon DC-Treg interaction reserving a possible feedback loop to generate more regulatory T cells [9, 10]. Another immunosuppressive cycle is the conversion of DCs by Treg-secreted INF-γ and CTLA-4 into an indolamine 2, 3-dioxigenase (IDO) expressing cells which induce Treg generation and effector T-cell apoptosis [11, 12].

Classically, CD4+ T cells have been categorized into Th1, Th2, Treg, and Th17 subsets. However, TGF-β has a crucial role in Treg and Th17 cell development, the dichotomy of Treg/Th17 is dependent on IL6. Only a few pieces of evidence has been reported on the presence and regulation of Th17 cells by IL-2 in human cancer and experimental tumors. Muranski et al. reported that tumor-specific Th17 polarized cells mediated successful treatment of large established tumor in cutaneous melanoma-bearing mice. The therapeutic effect of the cells was dependent on their INFγ production [13].

Modulating factors released by the tumor environment cause defective functional maturation of DCs and affect the differentiation of immature myeloid-derived suppressing cells (MDSCs). The portion of MDSC is significantly increased in spleen, peripheral blood, and bone marrow of tumor-bearing patients and correlates with tumor progression [14–16].

In conclusion, DCs are one of the potent regulator cells in tumor development. The effects of DCs in cancer patients are contraversial: several reports demonstrated that myeloid-derived MDCs induce effective antitumor immune response and tumor regression. In spite of this, the suppressive tumor environment can alter the properties of DCs. The functional defects of DCs have an essentional role in cancer patient to impede succesful antitumor immune response. These tolerogenic DCs function as tumor-promoting cells. The future challenge of anticancer-based therapies is to overcome DC tolerogenecity and to reduce their negative effects in tumor progression.

2. DENDRITIC CELL-BASED CANCER THERAPY

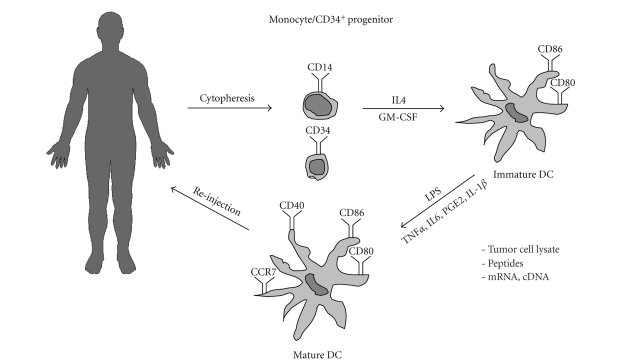

It is clear that however in low number DCs are present in tumors and can be used to elicit antitumor immune response. The challenge and goal of anticancer therapy is to elicit an effective cellular immune response against tumor cells and evoke clinical response in treated patients with negligible side effects. The discovery of isolation techniques and methods for differentiating DCs in vitro gave us the possibility to generate DCs that could be loaded by tumor-specific antigens or peptides. In this therapeutic approach, one can define DC-vaccine as a DC loaded with tumor-specific antigen. The first DC-based clinical trial against B-cell lymphoma was reported by Hsu et al. [17]. One important question in DC vaccination is to decide whether to use an ex vivo or in vivo vaccination strategy. The ex vivoapproaches (see Figure 1) allow to monitor the quality of the cells during the differentiation procedure, analyze cell surface markers, the proper maturation state, cell viability, or subtype specificity of DCs by FACS analysis. It is also possible to evaluate the effective tumor antigen-specific T-cell response by ELISpot, mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) before targeted DCs are introduced back to the patient. The possible sources of human DCs are CD34+ precursors, hematopoetic progenitors, and monocytes, isolated from blood by cytopheresis, adherent techniques or magnetic-based immunoselection, or immunodepletion [18–20]. IDCs can be differentiated from peripheral blood-derived monocytes in vitro in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 [18, 20]. Alternatively, DC precursors can be isolated from human peripheral blood, but for effective anticancer therapy one has to obtain high amount of targetable DCs. In a clinical trial, FLT-3 ligand-expanded DCs were prepared from the blood of colon and nonsmall cells of lung cancer patients. Because of the limited blood DC number, patients underwent FLT-3 treatment before DC isolation. As a result, three times more PBMC was obtained from these patients after standardized leukopheresis as compared to control patients. The isolated patient-derived DCs showed immature CD83−/CD40low/CD80low/CD86low phenotype, but after two days in culture, cells started to express CD83, elevated levels of CD86 and CCR7 proteins, which reflect MDC phenotype and migration capacity [21]. DC-vaccine studies utilize DCs loaded with peptide fragments or whole proteins providing an opportunity to present all potential peptide sequences of the antigen to recognize even more specific T-cell clones and tumor lysates exogenously [22]. Alternatively, one can target DCs endogenously with antigen-coded mRNA or cDNA [23]. After loading IDCs with tumor-specific antigens, it is very important to add adequate maturation agents (e.g., proinflammatory cytokines, LPS, CD40L) to ensure that DCs achieve their maximum migratory capacity to the lymph nodes, otherwise only a small portion of antigen-loaded DCs could migrate to the site of the naive T-cell activation. Following quality control steps, the generated DC vaccines have to be reinjected into the patients. An important issue is also the DC injection site. DC vaccines could be reinjected to patients by intravenous, subcutaneous, intradermal, or intralymphatic injections. In a clinical study, the efficiency of different injection sites was compared by Fong et al. [24]. According to their results, the intradermal or intralymphatic administration was more effective compared to intravenous injection. In general, DC delivery via the skin is preferable to intravenous injection. Combining the different routes of reinjections may be beneficial, depending on the tumor localization. Most of the early phase I clinical trials, using the ex vivo approach, have not shown long-term tumor regression or improved survival. Probably it is mostly due to the fact that in these studies the researchers selected only advanced-stage cancer patients who were immonosuppressed by recurrent tumors or by chemotherapy. However, an in vitro approach could provoke Th1 cell response in metastatic malignant melanoma [25].

Figure 1.

General scheme of anticancer vaccination. Dendritic cell progenitors (either CD34+ or CD14+ cells) are obtained using cytopheresis. Cells are differentiated using cytokines GM-CSF and IL-4. Immature dendritic cells are loaded with tumor lysate, peptides, or expression vector. DC maturation is induced and DCs are reinjected to patient.

As far as the migratory capacity of DCs is concerned, less than 5% of the MDCs reach the lymph nodes after intradermic injection [26]. Therefore, it would be more beneficial to activate and target DCs within the host. In this case, we are not concerned with cell isolation or differentiation protocols, but rather DC-initiated tumor-specific immune responses have to be monitored inside the body. Monoclonal antibodies and fusion construct can be used for more productive tumor antigen delivery directly into the DCs and probably the cells do not need to be cultured in vitro. Many vaccination studies target DC-specific c-type lectin receptors for efficient targeting of tumor antigens into the cells. These receptors bind to particular self- or nonself-sugar patterns by means of their carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) and have roles in endocytotic antigen uptake [27]. One of them, DEC205/DC205, is expressed at high levels by MDC in mice, but human B cells, NK cells, monocytes, and macrophages also express this receptor [28]. Bozzacco et al. designed a fusion monoclonal antibody construct by taking the light and heavy chain coding cDNA sequence of an anti-DEC205 antibody and by inserting different gag p24 peptides at the carboxy terminus of the heavy chain. According to their results, these antibodies increased antigen presentation in the treated HIV-infected patients. They could further demonstrate DC-primed cross-presentation of internalized, nonreplicating proteins to MHCI complexes inducing CD8+ T-cell activity [29]. These results support the feasibility of engineering tumor-specific peptide fragment into DC-targeted antibodies against various types of cancer in vivo.

3. THE ROLE OF THE PPARγ RECEPTOR IN DENDRITIC CELLS

3.1. PPARγ-altered phenotype of DCs

Nuclear hormone receptors are ligand-activated transcription factors. There are three different PPAR isoformes in the human body and these show distinct tissue-specific distribution with different physiological functions. PPARα is most highly expressed in the liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, and heart, and it regulates fatty acid oxidation [30]. PPARδ shows a ubiquiter distribution while PPARγ expression can be detected in various cell types like adipocytes, macrophages, and DCs. The receptor was initially described in mouse adipose tissue [31] and its role in myeloid development was shown by Nagy and Tontonoz in 1998 [32, 33]. PPARγ knockout mice are lipodystrophic and die of placental defect, showing the essential regulatory role for the receptors in embryonic differentiation [34]. Moreover, high level of PPARγ expression can be detected in monocyte-derived macrophages in atheroscleric lesions [33]. PPAR receptors heterodimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) in the nucleus and bind to certain receptor-specific response elements (PPREs) in the promoter or enhancer regions of their target genes [35]. The PPRE contains direct repeat sequences separated by one base pair (DR1). Endogenous or exogenous ligands bind into the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of PPARγ and modulate PPARγ-mediated gene expression. PPARγ can be activated by components of the oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) and prostaglandin derivate (e.g.,15d-PGJ2) [32, 36]. Ligand activation of the receptor induces the expression of CD36 scavenger receptor which in turn leads to oxLDL uptake of macrophages and this metabolic process can lead to foam cell formation [32]. From these studies, we know that PPARγ regulates fatty acid uptake into the cell by induced cell surface receptors and it also promotes lipid storage and accumulation. Beside this fundamental regulatory role in metabolism, the receptor also functions as a key modulatory factor in macrophage immune function [37]. Earlier microarray data suggested that the PPARγ gene is upregulated during monocyte-to-DC differentiation [38]. According to our experiments and those of others, the receptor is immediately upregulated in cultured DCs, while it is barely detectable in monocytes [39]. We have shown that the transcription factor in this system is active, because synthetic agonists induce dose-dependent gene expression of the bone fide PPARγ target gene FABP4 in IDCs [39, 40]. Through global gene expression analysis, we found that PPARγ-activated genes involved primarily in the first 6 hours are involved primarly in lipid metabolism and transport (CD36, LXRα, and PGAR). Genes, coupled to the immune regulatory role of human DCs, were upregulated only for 24 and 120 hours after ligand treatment. It is possible that immunophenotype of DCs could be altered by PPARγ activation indirectly through activation of lipid metabolism and signaling pathways [41].

In terms of DC-based vaccination therapy, the most important question is how PPARγ activation might effect the DC-initiated immune responses and DC phenotype. PPARγ expression was first detected in murine DCs by Faveeuw et al. and they reported that there is a PPARγ receptor-dependent inhibition of IL-12 secretion of IDCs and MDCs [42]. Furthermore, it was also shown that PPARγ ligand activation caused anti-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages [37]. These findings support the idea that PPARγ might have an essential role in the APC-based DC-vaccine therapies. The DC-secreted IL-12 is indispensable for Th1 cell promotion and CD8+ T-cell activation. Earlier publications by Gosett et al. and Nencioni et al. assessed that PPARγ ligand activation alters the immunogenicity of human monocyte-derived DCs [43, 44]. During DC maturation, costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86) are upregulated on the surface of DCs [2]. Some bacterial products, such as LPS, are able to induce signals via TLR receptors or CD40 molecules induce IL-12 secretion of DCs. They have also found that upon ligand activation of PPARγ, the phenotype and cytokine expression patterns of the cells were changed [43]. PPARγ ligands altered iDC-specific surface markers involved in APC function. The CD83 activation marker expression in treated MDCs was uneffected, which means that PPARγ ligand-activated cells showed mature phenotype. After ligand activation, elevated CD86 protein level was detected on the surface of MDCs. They also showed that activation of PPARγ inhibits the secretion of IL-12p70 active form into the supernatant by MDCs while the levels of IL-6 and IL-10 were unchanged. Furthermore, chemokines involved in Th1 cell recruitment (IP-10, RANTES, and MIP1α), were also decreased after ligand treatment in the same study. Nencioni et al. later characterized the effects of PPARγ on DC maturation and found that ligand activation reduced the surface expression of CD1a molecule in a concentration-dependent manner, resulting in an unusual phenotype of differentiated IDCs [44]. Lower levels of IL-10, IL-6, and TNFα cytokines were measured upon ligand treatment. PPARγ agonist impaired the allogenic T-cell stimulating capacity in MLR assays and the secreted INFγ concentration was also reduced. T-cell activation capacity could not be restored by IL-12 administration suggesting that the impaired T-cell activation of MDCs was not only due to lack of IL-12 expression but also to other effects that modulate DC maturation process were involved.

In conclusion, the PPARγ ligand-activated cells not only impede the naive T cell to Th1 cell differentiation, but these cells also showed decreased antigen-specific T-cell response. Appel et al. reported that important anti-inflammatory effects of the receptor as ligand activation of the PPARγ receptors inhibited the LPS-activated MAP kinase and NF-κB proinflammatory signaling pathways, probably due to transrepression mechanism in DCs that subvert IL-12 expression [45].

Flow cytometry measurements performed by some of us largely supported the phenotypic results reviewed above [39]. Furthermore, when treated DCs with PPARγ, we detected that enhanced endocytosis in the form of enhanced latex bead uptake and ligand-treated cells were CD1a−. We could not detect any differences in case of HLA-ABC molecule expression, suggesting that the MHCI-mediated peptide antigen presentation capacity of the cell is probably not affected [46]. As reported by Angeli, PPARγ inhibits the expression of CCR7 on the surface of MDCs and this decreased the migration of DCs in mice. In this model, TNFα-induced epidermal LC motility from epidermis to dermal lymph nodes was reduced by PPARγ ligand treatment. They also found that ligand-activated PPARγ impaired the steady-state migration of DCs from the mucosal to the thoracic lymph nodes, but the maximal inhibitory effect was detected at a considerably high concentration of the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (10 μM) that suggested receptor-independent effects [47].

Summarizing these data, PPARγ activation in DCs prevented IL-12 secretion, lowered CD80/CD86 ratio, and probably shifted naive T-cell differentiation toward Th2 cells. According to our own experiments, PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone at 2.5 μM concentration did not decrease the activation of allogeneic T cell and INFγ production [39]. So far, no one was able to detect Th2 response in MLR in response to PPARγ ligand activation.

3.2. The role of PPARγ in CD1d-mediated lipid antigen presentation

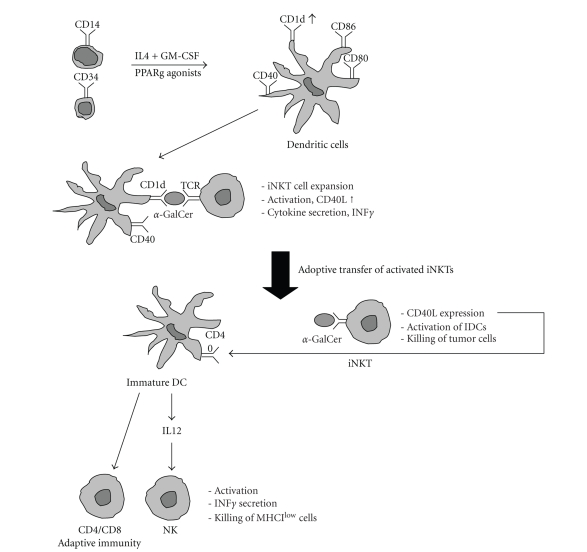

Szatmari et al. provided evidence that PPARγ activation could effect the lipid antigen presentation capacity of monocyte-derived DCs through upregulated expression of CD1d molecule on the surface of DCs [39]. This finding links PPARγ to invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells. After isolation, monocytes fail to express CD1 group I molecules (CD1a, b, c) but the CD1a protein is upregulated during monocyte-to-IDC differentiation [20]. Inversely, the CD1 group II molecule CD1d is expressed at high levels on monocytes and downregulated on the surface of DCs [39]. Induced signaling pathways are able to regulate CD1d gene expression and lipid metabolism upon PPARγ ligand treatment [41]. Utilizing PPARγ agonist treatment, Gogolak et al. could induce the expression of CD1d molecules along with downregulation of CD1a at both mRNA and protein levels [48]. Later we established that PPARγ ligand activation enhanced indirectly the CD1d expression by turning on endogenous lipophilic ligand synthesis in the DCs through activation of the expression of retinol dehydrogenase 10 (RDH10) and retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (RALDH2) enzymes, which are involved in retinol and retinal metabolism and endogenous all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) production from retinol [46]. The intracellularly synthesized ATRA induced CD1d and other retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) target genes in DCs. We looked at the functional role of PPARγ-induced retinoid-regulated CD1d expression on DC surface. DCs pulsed with synthetic alpha-galactosilceramide (αGalCer) ligand for 24 hours elevated iNKT cell expansion and INFγ secretion [39, 41]. As CD1d-mediated lipid antigen presentation is essential for iNKT cell activation, we could conclude that PPARγ-induced CD1d expression can be translated to the increased activation and proliferation of iNKT cells under these in vitro conditions [39]. Our results suggest that combination of PPARγ activator ligands along with αGalCer during the differentiation of DCs might be beneficial in iNKT-based adoptive transfer therapy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The molecular basis for the potential use of PPARγ-programed dendritic cells during tumor vaccination. DC progenitors are differentiated in the presence of PPARγ agonists. A PPARγ-programed DC showed increased CD1d expression. In the presence of αGalCer, the treated DC is capable of inducing iNKT cell expansion. The adoptively transfered iNKTs can induce activation of iDCs and IL-12 secretion in cancer patients. This can lead to improved ability to kill tumor cells.

4. CD1d-RESTRICTED iNKT CELLS IN CANCER THERAPY

4.1. iNKT cell-based anticancer effects in animal models

Besides DCs and T cells, there are other important cell types contributing to antitumor immunity. iNKT cells are a unique T-lymphocyte population. These cells share both NK (CD161) and T-cell-specific markers (TCRs) on their surfaces. iNKT cells have restricted T-cell receptors (TCRs): in mice, the most frequently expressed α-chain rearrangement is Vα14-Jα18 while human NKT cells express Vα24-Jα18/Vβ11 TCRs (reviewed by Godfrey and Kronenberg [49]). For iNKT activation, it is essential to interact with cells displaying the evolutionarily conserved CD1d, nonclassical antigen-presenting molecules that present glicolipids in the context of hydrophobic antigen binding to these cells [50, 51]. αGalCer is the most frequently used lipid ligand for iNKT activation. It is derived from a marine sponge.

αGalCer has shown antimetastatic activity in various experimental tumor models (e.g., B16 melanoma, Lewis lung carcinoma, FBL-3 erytroleukemia, Colon26, and RMA-S 3LL tumor cells) in vivo [52–54]. This effect of the compound was tested in CD1d−/−, Ja281−/− RAG−/− NKT mice, which have no iNKT cells and in NK-depleted wild-type mice. The results indicated that the antitumor effect of the glycolipid was abolished on all of the three tested genetic backgrounds in mice and the αGalCer-mediated antimetastatic function likely acts through iNKT cell activation and NK-like effector function [52]. Adoptive transfer experiments provided further proof for the key role of iNKT cell-secreted INFγ in the antimetastatic role of αGalCer in mice. Furthermore, activation and proliferation of NK cells downstream to iNKT activation, and subsequent INFγ production was also required to be essential for antimetastatic cytotoxic activity in vitro and in vivo [55, 56]. αGalCer activates iNKT cells, which produce INFγ, and secondary activates NK cells. These activated NK cells have been implicated also in the regulation of angiogenesis during tumor development. The αGalCer treatment inhibits the subcutaneous tumor growth, tumor-induced angiogenesis, and epithelial cell proliferation, which are required for tumor vessel formation [57]. Later it has been established that αGalCer treatment, in combination with IL-21, prolonged and elevated the NK cell cytotoxicity, maturing NK cells into perforine-expressing cells by IL-21. Moreover, this combination inhibited spontaneous tumor metastases. Presentation of αGalCer by DC to iNKT cells in contrast to soluble compound injection was even more effective in the suppression of metastasis formation [58]. Similar successful antitumor effects of αGalCer-pulsed DC have been published by Toura et al. using B16 melanoma liver metastasis and lung metastasis of LLC model in vivo. Beside the inhibition of metastatic nodule formation in these tissues, αGalCer-DC administration also has a significant beneficial effect in the regression of established nodules [59, 60].

4.2. iNKT cells in human cancer therapy

Human Vα24+ iNKT cells also mediate αGalCer-dependent antitumor activity by perforin-dependent cytotoxic lysis against Daudi lymphoma and other various cell lines [53, 61]. Others demonstrated effective direct iNKT-mediated cytotoxicity only against CD1d+ cell lines such as U937, while CD1d− cell lines were killed only after CD1d transfection into the cells. NKT cells provoked NK cell-induced cytotoxitity by IL-2 and INFγ secretion [62].

The crosstalk between innate and adaptive immunity was established in several anticancer studies. This linkage could be mediated via reciprocal interaction between iNKT cells and iDCs. Upon αGalCer activation, iNKT cells express CD40L [63]. The CD40 ligand binds to the CD40 molecules of DCs and triggers IL-12 expression and secretion by the DCs. The produced IL-12 generates a positive feedback and induces INFγ secretion by the iNKTs [63, 64]. The secondary activation of DCs leads to NK, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell activation by standard activation of memory T cells and adaptive immune response against peptides presented by DCs [65–67].

The fact that αGalCer-loaded DC could trigger iNKT expansion and mediate antitumor immune response in several in vitro experiments and in vivo antimetastatic models in mice supported the notion that using αGalCer-pulsed DCs for iNKT activation in cancer patients in situ might induce an effective anticancer therapy. Other alternative approach could be the adoptive transfer of in vitro expanded and activated iNKT cells to patients.

The number of NKT cells in cancer patients is significantly lower compared to healthy volunteers. Giaccone et al. showed the disappearance of iNKT cells after 24 hours of αGalCer administration from the peripheral blood of patients and only transient iNKT activation was registered in some individuals [68]. Others found quantitative defects in iNKT cell-derived INFγ production among patients with advanced prostate cancer [69]. Showing that NK cells were able to respond to IL-12, those cells could secrete increased levels of INFγ demonstrating the selective loss of INFγ-secreting capacity of iNKT cells in patients [69]. As it was expected from mouse experiments, Chang et al. were able to expand the number of iNKT cells for more than a month in all treated patients, proving that αGalCer-pulsed MDCs could be more effective than using αGalCer-pulsed IDC or the soluble compound [70]. However, the levels of IL-12p40 and IL-10 in the serum were elevated after the treatment and iNKT cells showed reduced-INFγ secretion. The future challenge of this type of tumor therapy is to induce extended iNKT number and activity. One possible approach is to use additional pharmacological ligands upon cancer therapies. It has been shown that the thalidomide analogue, lenalidomide (LEN), enhanced the predominant iNKT cell expansion in vitro and in vivo in response to αGalCer-loaded DC. LEN elicits higher level of INFγ secretion in response to αGalCer-loaded DC, suggesting that LEN might be restoring the INFγ-producing activity of iNKT cells in cancer patients [71]. Alternative possibility is the adoptive transfer method: in phase I clinical trial, adoptive transferred iNKTs were used in patients with malignancy to increase the number of iNKT cells [72]. They expanded iNKT cells in vitro in the presence of IL-2 and αGalCer. The activated iNKT cells showed cytotoxic activity against PC-13 and Daudi human cancer cell lines. Reinjection of activated iNKT cell into the patients enhanced the level of INFγ secreting iNKT cells in the peripheral blood from day one up to two weeks [72].

5. DENDRITIC CELL PPARγ IN ANTICANCER THERAPY

Despite the enormous research effort, cancer is still a significant clinical problem as well as basic science problem. However, immunotherapy opened up some possibility in the fight against cancer. General APC features of DCs are capturing antigens in the periphery, processing, and enhancing MHC-peptide complex presentation capacity to naive T cells. These phenomena highlighted possible roles for DCs in anticancer therapy. However, DC-based vaccination often does not elicit clinical responses and fails to ensure long-time tumor regression in patients with malignant tumors. One reason for this failure could be the immunosuppressed state of the patient, for example, due to chemotherapy in the therapeutical history. Recently, we have identified a new target gene, ABCG2, which is transcriptionally regulated by PPARγ in DCs. ABCG2 transporters modify the drug resistance against anticancer agent of PPARγ agonist-treated DCs. PPARγ has a protective function in these cells, and using PPARγ-specific ligands during in vitro differentiation could revert the xenobiotics-induced toxicity in DCs [73].

Due to the fact that we did not find reduced capacity of DCs to activate T cell in MLR assays, we concluded that ligand activation does not suppress DC-mediated peptide antigen presentation. For effective anticancer therapy, one should provoke adaptive immune response against tumor-specific peptides presented by DCs. In mouse experiments, simultaneously added αGalCer and peptide-loaded DCs induced CD4/CD8 T-cell-specific anticancer immune response mediated by iNKT cell. In case of human patients, αGalCer-loaded DCs could not induce adaptive immunity, partly because of the ineffective INFγ secretion by iNKT cells. Pharmacological approaches like LEN may solve this problem. The ability of PPARγ to upregulate CD1d expression on DCs raises the possibility to use receptor agonists in iNKT-based adoptive transfer treatments.

Many features of DCs, which are critical during DC-vaccination design, are affected by PPARγ. Reduced migratory capacity, inhibited IL-12 cytokine production, inadequate Th1 and CD8+ T-cell response, and presumed generation of IL-10-producing tolerogenic DC could influence the outcome of DC-based vaccination therapies against cancer. Based mainly on these in vitro results, activation of the PPARγ receptor in tumor peptide-pulsed DCs could be less beneficial in terms of in vivo vaccination strategies. At the same time, increased phagocytic capacity, increased CD1d expression, and iNKT activation potential are useful features of PPARγ-programed DCs. In spite of the vast amount of in vitro obtained results on the potential role of PPARγ in DCs, the most controversial issue remains open: whether synthetic PPARγ agonists have significant modifying effects on antitumor immune response in vivo or not. Further in vivo studies are needed to clarify the receptor-specific immunomodulatory effects of PPARγ ligands (agonists or antagonists) in cancer patients. For that, the use of siRNA-based gene-silencing techniques or DC-specific PPARγ, KO animal models would probably be useful.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work in the author's laboratory is supported by a grant from the National Research and Technology Office RET-06/2004 to L. Nagy; and one from the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA no. NK72730). L. Nagy is an International Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and holds a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Biomedical Sciences in Central Europe no. 074021.

References

- 1.Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice: I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1973;137(5):1142–1162. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dadabayev AR, Sandel MH, Menon AG, et al. Dendritic cells in colorectal cancer correlate with other tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2004;53(11):978–986. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandel MH, Dadabayev AR, Menon AG, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in colorectal cancer: role of maturation status and intratumoral localization. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(7):2576–2582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Donnell RK, Mick R, Feldman M, et al. Distribution of dendritic cell subtypes in primary oral squamous cell carcinoma is inconsistent with a functional response. Cancer Letters. 2007;255(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(5):2756–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cederbom L, Hall H, Ivars F. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells down-regulate co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2000;30(6):1538–1543. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1538::AID-IMMU1538>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oderup C, Cederbom L, Makowska A, Cilio CM, Ivars F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4-dependent down-modulation of costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression. Immunology. 2006;118(2):240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zou L, et al. Cutting edge: induction of B7-H4 on APCs through IL-10: novel suppressive mode for regulatory T cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(1):40–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahnke K, Ring S, Johnson TS, et al. Induction of immunosuppressive functions of dendritic cells in vivo by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells: role of B7-H3 expression and antigen presentation. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(8):2117–2126. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Hwang KW, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(12):1206–1212. doi: 10.1038/ni1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellor AL, Munn DH. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4(10):762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muranski P, Boni A, Antony PA, et al. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112(2):362–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, et al. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;166(1):678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronte V, Serafini P, Apolloni E, Zanovello P. Tumor-induced immune dysfunctions caused by myeloid suppressor cells. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2001;24(6):431–446. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2006;55(3):237–245. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu FJ, Benike C, Fagnoni F, et al. Vaccination of patients with B-cell lymphoma using autologous antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. Nature Medicine. 1996;2(1):52–58. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romani N, Gruner S, Brang D, et al. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180(1):83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardavín C, Martínez del Hoyo G, Martín P, et al. Origin and differentiation of dendritic cells. Trends in Immunology. 2001;22(12):691–700. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor α . The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(4):1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong L, Hou Y, Rivas A, et al. Altered peptide ligand vaccination with Flt3 ligand expanded dendritic cells for tumor immunotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(15):8809–8814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141226398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(3):328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Tendeloo VFI, Ponsaerts P, Lardon F, et al. Highly efficient gene delivery by mRNA electroporation in human hematopoietic cells: superiority to lipofection and passive pulsing of mRNA and to electroporation of plasmid cDNA for tumor antigen loading of dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98(1):49–56. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong L, Brockstedt D, Benike C, Wu L, Engleman EG. Dendritic cells injected via different routes induce immunity in cancer patients. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;166(6):4254–4259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuler-Thurner B, Schultz ES, Berger TG, et al. Rapid induction of tumor-specific type 1 T helper cells in metastatic melanoma patients by vaccination with mature, cryopreserved, peptide-loaded monocyte-derived dendritic cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195(10):1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vries IJM, Krooshoop DJEB, Scharenborg NM, et al. Effective migration of antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to lymph nodes in melanoma patients is determined by their maturation state. Cancer Research. 2003;63(1):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y, Adema GJ. C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells and langerhans cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(2):77–84. doi: 10.1038/nri723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato M, McDonald KJ, Khan S, et al. Expression of human DEC-205 (CD205) multilectin receptor on leukocytes. International Immunology. 2006;18(6):857–869. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bozzacco L, Trumpfheller C, Siegal FP, et al. DEC-205 receptor on dendritic cells mediates presentation of HIV gag protein to CD8+ T cells in a spectrum of human MHC I haplotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(4):1289–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610383104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-α, -β, and -γ in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPARγ2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes & Development. 1994;8(10):1224–1234. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JGA, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ . Cell. 1998;93(2):229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JGA, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARγ promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, et al. PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(4):585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature. 1992;358(6389):771–774. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ . Cell. 1995;83(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391(6662):79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Naour F, Hohenkirk L, Grolleau A, et al. Profiling changes in gene expression during differentiation and maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells using both oligonucleotide microarrays and proteomics. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(21):17920–17931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szatmari I, Gogolak P, Im JS, Dezso B, Rajnavolgyi E, Nagy L. Activation of PPARγ specifies a dendritic cell subtype capable of enhanced induction of iNKT cell expansion. Immunity. 2004;21(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of adipocyte gene expression and differentiation by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ . Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 1995;5(5):571–576. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szatmari I, Töröcsik D, Agostini M, et al. PPARγ regulates the function of human dendritic cells primarily by altering lipid metabolism. Blood. 2007;110(9):3271–3280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faveeuw C, Fougeray S, Angeli V, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activators inhibit interleukin-12 production in murine dendritic cells. FEBS Letters. 2000;486(3):261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosset P, Charbonnier A-S, Delerive P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activators affect the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2001;31(10):2857–2865. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2857::aid-immu2857>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nencioni A, Grünebach F, Zobywlaski A, Denzlinger C, Brugger W, Brossart P. Dendritic cell immunogenicity is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . The Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(3):1228–1235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Appel S, Mirakaj V, Bringmann A, Weck MM, Grünebach F, Brossart P. PPAR-γ agonists inhibit toll-like receptor-mediated activation of dendritic cells via the MAP kinase and NF-κB pathways. Blood. 2005;106(12):3888–3894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szatmari I, Pap A, Rühl R, et al. PPARγ controls CD1d expression by turning on retinoic acid synthesis in developing human dendritic cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203(10):2351–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angeli V, Hammad H, Staels B, Capron M, Lambrecht BN, Trottein F. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ inhibits the migration of dendritic cells: consequences for the immune response. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(10):5295–5301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gogolak P, Rethi B, Szatmari I, et al. Differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells is biased by lipid environment and PPARγ . Blood. 2007;109(2):643–652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(10):1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burdin N, Brossay L, Koezuka Y, et al. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: α-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates Vα14+ NK T lymphocytes. The Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(7):3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(8):557–568. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated Vα14 NKT cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(10):5690–5693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawano T, Nakayama T, Kamada N, et al. Antitumor cytotoxicity mediated by ligand-activated human Vα24 NKT cells. Cancer Research. 1999;59(20):5102–5105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Pellicci DG, et al. Sequential production of interferon-γ by NK1.1+ T cells and natural killer cells is essential for the antimetastatic effect of α-galactosylceramide. Blood. 2002;99(4):1259–1266. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, et al. Cutting edge: cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(9):4647–4650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, et al. Critical contribution of IFN-γ and NK cells, but not perforin-mediated cytotoxicity, to anti-metastatic effect of α-galactosylceramide. European Journal of Immunology. 2001;31(6):1720–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, et al. IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by natural killer T-cell ligand, α-galactosylceramide. Blood. 2002;100(5):1728–1733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smyth MJ, Wallace ME, Nutt SL, Yagita H, Godfrey DI, Hayakawa Y. Sequential activation of NKT cells and NK cells provides effective innate immunotherapy of cancer. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(12):1973–1985. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toura I, Kawano T, Akutsu Y, Nakayama T, Ochiai T, Taniguchi M. Cutting edge: inhibition of experimental tumor metastasis by dendritic cells pulsed with α-galactosylceramide. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(5):2387–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Kronenberg M, Steinman RM. Prolonged IFN-γ-producing NKT response induced with α-galactosylceramide-loaded DCs. Nature Immunology. 2002;3(9):867–874. doi: 10.1038/ni827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi T, Nieda M, Koezuka Y, et al. Analysis of human Vα24+CD4+ NKT cells activated by α- glycosylceramide-pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;164(9):4458–4464. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Metelitsa LS, Naidenko OV, Kant A, et al. Human NKT cells mediate antitumor cytotoxicity directly by recognizing target cell CD1d with bound ligand or indirectly by producing IL-2 to activate NK cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(6):3114–3122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomura M, Yu W-G, Ahn H-J, et al. A novel function of Vα14+CD4+NKT cells: stimulation of IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells in the innate immune system. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(1):93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand α-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;189(7):1121–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, et al. Requirement for Vα14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278(5343):1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eberl G, MacDonald HR. Selective induction of NK cell proliferation and cytotoxicity by activated NKT cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2000;30(4):985–992. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200004)30:4<985::AID-IMMU985>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujii S, Liu K, Smith C, Bonito AJ, Steinman RM. The linkage of innate to adaptive immunity via maturing dendritic cells in vivo requires CD40 ligation in addition to antigen presentation and CD80/86 costimulation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;199(12):1607–1618. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giaccone G, Punt CJA, Ando Y, et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand α-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 2002;8(12):3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tahir SAM, Cheng O, Shaulov A, et al. Loss of IFN-γ production by invariant NK T cells in advanced cancer. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(7):4046–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang DH, Osman K, Connolly J, et al. Sustained expansion of NKT cells and antigen-specific T cells after injection of α-galactosyl-ceramide loaded mature dendritic cells in cancer patients. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(9):1503–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang DH, Liu N, Klimek V, et al. Enhancement of ligand-dependent activation of human natural killer T cells by lenalidomide: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2006;108(2):618–621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Motohashi S, Ishikawa A, Ishikawa E, et al. A phase I study of in vitro expanded natural killer T cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(20):6079–6086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szatmari I, Vámosi G, Brazda P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-regulated ABCG2 expression confers cytoprotection to human dendritic cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(33):23812–23823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]