Abstract

Benzophenone photophores are employed widely for photoaffinity-labeling studies. Photolabeling with benzophenone, however, is hardly a routine experiment. Even when a photoprobe binds to its target, photocrosslinking does not necessarily occur. This is because photolabeling by benzophenone is affected by many factors other than target-binding, such as conformational flexibility of photoligand. Despite the widespread recognition of such complications, there has been no systematic study to assess the relative importance of individual factors that can affect photolabeling efficiency. In order to gain an insight into this problem, we conducted a structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of benzophenone photoligands for Lck kinase, in which photoligands with varying target binding-affinity and conformational flexibility were compared. The study found that binding-affinity, as indicated by kinase inhibitory potency, did not correlate with photolabeling efficiency. Instead, conformational flexibility was found to be the determining factor for efficient photolabeling by our photoligands. Implication of the current findings, in particular, with regard to selection and optimization of benzophenone photoligands, is discussed.

Keywords: photoaffinity, Bpa, biotin, adenine, SAR, chemical proteomics

1. Introduction

Benzophenone is probably the most popular photophore for photoaffinity-labeling. It has been widely employed in studies on protein-ligand interactions and drug-target identification.1–5 Recently, the use of benzophenone surged in the field of chemical proteomics, in which molecular tools are employed to selectively tag families of proteins in complex proteomes.6–13 Despite its widespread use, photolabeling with benzophenone is hardly a routine experiment. It is not uncommon that a promising benzophenone ligand, which retains biological activities of the original ligand, turns out to be a poor photolabeling agent. Although many factors, including binding-affinity and flexibility of ligands, are known to affect the outcome of photolabeling experiments,1–3 their relative importance has not been systematically evaluated.

Since target-binding is a prerequisite for photolabeling, binding-affinity, as assessed by Kd, Ki, IC50, etc., is commonly used to select and optimize benzophenone probes for photocrosslinking experiments.14 There are, however, cases in which binding-affinity does not correlate with photolabeling efficiency. For example, in a recent study of benzophenone probes for histone deacetylases,9 enzyme inhibitory potency was not indicative of the photolabeling efficiency. Likewise, a similar discrepancy between binding affinity and photolabeling efficiency can be seen in a study on secretin analogs containing benzophenone.15 Such observations suggest that factors other than binding affinity are controlling the outcome of photoaffinity-labeling, although existing literature on benzophenone photoligands does not delve into such problems but rather focuses on successful examples.

One of the major factors that can control photolabeling experiments is conformational flexibility. It is well-known that conformational flexibility significantly affects specificity and efficiency of benzophenone photoligands.1,2 When specificity of labeling is important, as is the case for studies on ligand-receptor interactions, probes are designed to minimize flexibility so as to accomplish site-specific labeling.16 On the other hand, when high efficiency of photolabeling is desired, as is the case for applications in chemical proteomics, minimizing flexibility may or may not be a good idea. In theory, conformational restriction can improve labeling efficiency if it pre-organizes a ligand for target binding. On the other hand, conformational restriction can decrease the rate of photochemical reactions as demonstrated by a series of studies on intramolecular photoreactions of benzophenone derivatives.17,18 Thus, although it is known that flexibility has an effect on photolabeling efficiency, it remains difficult to predict how it actually affects the efficiency.

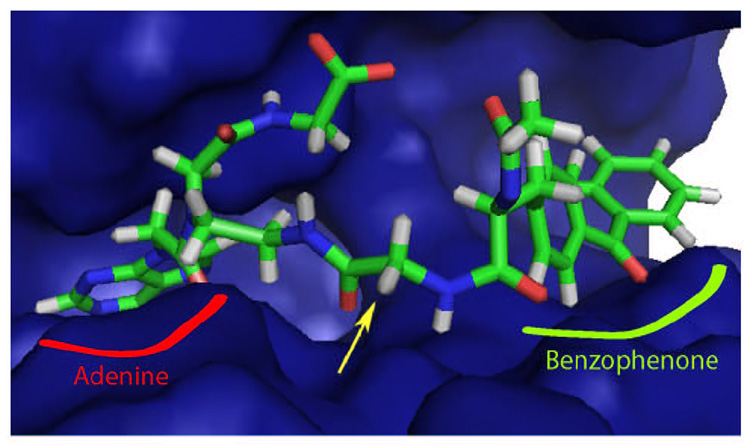

In order to gain insights into the relative importance between target-binding affinity and conformational flexibility, we conducted a structure-activity relationship (SAR) study on benzophenone photoligands for Lck kinase, which is a Src-family kinase involved in a variety of physiological and pathological processes, including thymocyte differentiation, T-cell activation, lymphocyte malignancy and immunodeficiency.19–23 The current work is based on our earlier finding, in which a small structural motif containing adenine and benzophenone can selectively photolabel Lck kinase.24 The same study determined the photocrosslinking site on Lck, which enabled us to build a model of ligand-Lck complex (Fig. 1). The model suggested that the central Gly residue, highlighted by the yellow arrow in Figure 1, could be replaced with d-amino acids without disturbing the existing interactions with the Lck surface. In this report, we first present the design and synthesis of new Lck photoligands with different amino acid residues in the central Gly position. We then show Lck inhibitory potency, photolabeling efficiency, and UV stability of individual probes. These results collectively suggest that higher conformational flexibility, but not higher binding affinity, is associated with more efficient photolabeling. We discuss the implication of our findings, especially for the applications of benzophenone in chemical proteomics.

Figure 1.

The model of the Lck-Ligand complex. The central Gly between PNA-adenine and Bpa is highlighted by the yellow arrow. For clarity the biotin moiety is removed in this figure.

2. Results

2.1. Design and synthesis of new Lck photoligands

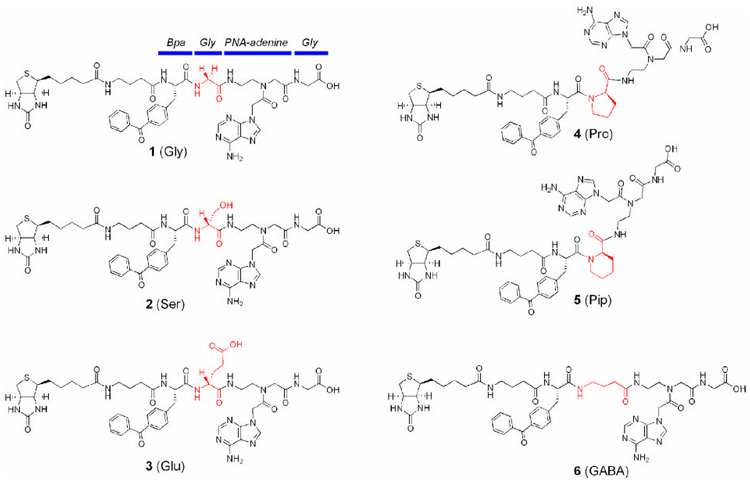

Figure 2 shows the new Lck photoligands examined in the current study. Compound 1 contains the original “Lck-targeting” framework consisting of p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (Bpa), Gly, PNA-adenine, and Gly (Fig. 2).24 The biotin moiety in 1 is used for the detection of photocrosslinked Lck by streptavidin-HRP. Compounds, 2 (“Ser” ligand) and 3 (“Glu” ligand), have d-Ser and d-Glu, respectively, in the place of the Gly between Bpa and PNA-adenine. These two compounds were designed based on the premise that higher binding affinity, which may be gained through additional hydrogen bonds or salt bridge, leads to improved photolabeling efficiency; Figure S1 summarizes the possible hydrogen-bond and/or salt bridge partners in the vicinity of the central Gly (see Supplementary data). Compounds 4 (“Pro” ligand) and 5 (“Pip” ligand), containing cyclic d-amino acids in the place of the central Gly, are conformationally restricted analogs of 1. These compounds were designed to prepay the entropic penalty for binding. The structures of 4 and 5 indeed mimic the bent conformation of photoligand bound to Lck (Fig. 1).24 Compound 6, on the other hand, contains γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the place of the central Gly. Thus, 6 (“GABA” ligand) serves as a probe to determine the effects of increased flexibility.

Figure 2.

Structures of newly synthesized Lck photoligands. The “Lck-targeting motif” is highlighted by the blue bars in 1 (Gly). The glycine between Bpa and PNA-adenine in 1 (shown in red) is replaced with different amino acid residues. See text for more details.

All compounds were synthesized using a standard Fmoc-chemistry as described previously.6,24

2.2. Lck inhibition assay

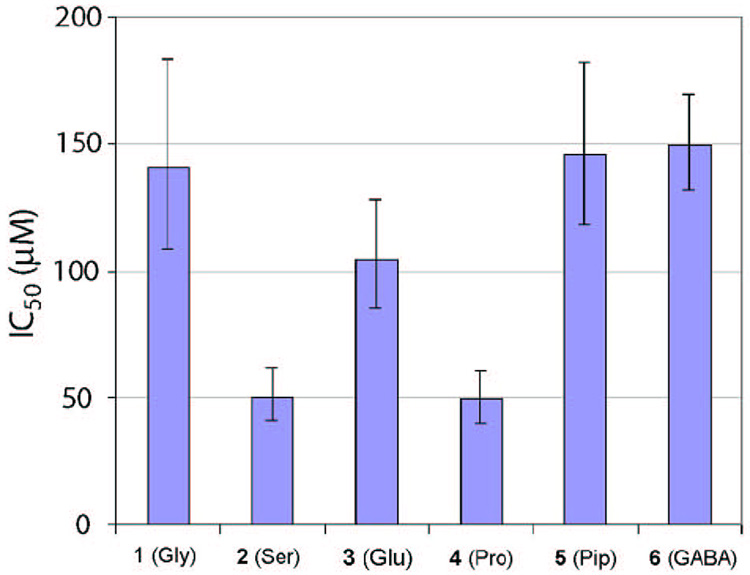

In order to assess the target-binding affinity of synthesized compounds, we conducted a kinase inhibition assay. The activities of Lck kinase in the presence and absence of photoligands were determined with an endpoint assay using a commercial kit (Promega Kinase-Glo® Plus Luminescent Kinase Assay),25 in which residual ATP at the end of each kinase reaction was quantified by luciferase; in order to prevent non-specific inhibition of Lck kinase by compound-aggregates, 0.01% Triton-X100 was included in the kinase buffer.26 The obtained IC50 values of photoligands are summarized in Figure 3. None of these compounds were potent inhibitors of Lck. Importantly, however, this assay still allowed us to assess their relative binding-affinity to Lck.

Figure 3.

The IC50 values of Lck photoligands. Lck kinase reactions in the presence and absence of photoligands were carried out on a 384-well plate. Following the incubation, residual ATP in each well was quantified with Promega Kinase-Glo® Plus Luminescent Kinase Assay. See the Experimental section for more details.

Compounds 2 (Ser) and 4 (Pro) turned out to have the highest affinity to Lck among six compounds, as indicated by their lowest IC50 values (both, ~50 µM). These results indicated that the presence of d-Pro indeed pre-organized 4 for target-binding, whereas 2 can form extra hydrogen bond(s) with the Lck surface. Compounds 1 (Gly), 3 (Glu), 5 (Pip), and 6 (GABA) were all equally poor binders to Lck as indicated by the high IC50 values; the differences among these compounds were not statistically significant. The result of 3 (Glu) indicated that the carboxylate group did not pick extra interactions with the protein. The poor binding of 5 (Pip) suggested that this compound was fixed in a wrong conformation. It was not surprising that the most flexible compound, 6 (GABA), was among the poorest binders as the molecule was expected to pay large entropic penalty for target-binding. The compounds with defined binding affinity to Lck were then subjected to photoaffinity-labeling analysis.

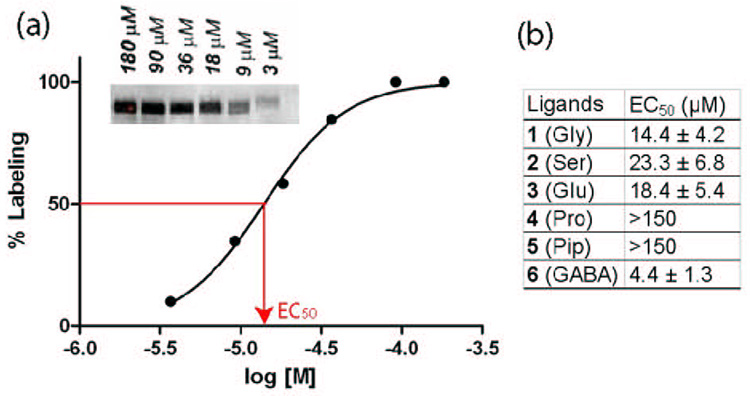

2.3. Photocrosslinking efficiency

Photolabeling efficiencies of newly prepared compounds were assessed by half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values, i.e., the ligand concentrations at which 50% of the maximum labelling was observed (Fig. 4a). Lck was photocrosslinked with ligands at various concentrations (0, 3, 9, 18, 36, 90, and 180 µM). The resulting titration curves were used to obtain EC50 values. Compound 1 (Gly) labeled Lck efficiently with the EC50 value of 14.4 µM. To our surprise, compound 4 (Pro), which exhibited the highest binding affinity to Lck, did not label Lck efficiently (EC50 > 150 µM). The most flexible one, compound 6 (GABA), on the other hand, exhibited the best photolabeling efficiency (EC50= 4.4 µM), even though it was one of the poorest binder to Lck. The labeling efficiencies of 2 (Ser) and 3 (Glu) were comparable to that of 1. Thus, the enhanced binding-affinity of 2 did not translate into higher photolabeling efficiency. The photolabeling by compounds, 1, 2, 3, and 6, was completely blocked by an ATP-competitive inhibitor of Lck (Figure S2 in Supplementary Data),27, 28 indicating that the probes bound specifically to the active site of Lck.

Figure 4.

Photoaffinity-labeling study of newly synthesized Lck ligands. (a) The gel image of Lck tagged with different concentrations of 1, and the resulting titration curve, from which EC50 was estimated. (b) EC50 values of all photoligands: triplicate experiments (n=3) were made for each data point.

These results indicated that the conformational flexibility, but not the binding affinity, was the determining factor for high photolabeling efficiency of our photoligands. There remained, however, one other possibility that could explain the poor labeling of 4 (Pro). The possibility was that the bent structure of 4 could facilitate intramolecular photochemical reactions.17, 18, 29 If 4 decomposed much faster than 1 under UV due to intramolecular photoreactions, the accelerated decomposition could also account for the diminished labeling efficiency. We, therefore, decided to assess this possibility.

2.4. Decomposition of free photoligands under UV light

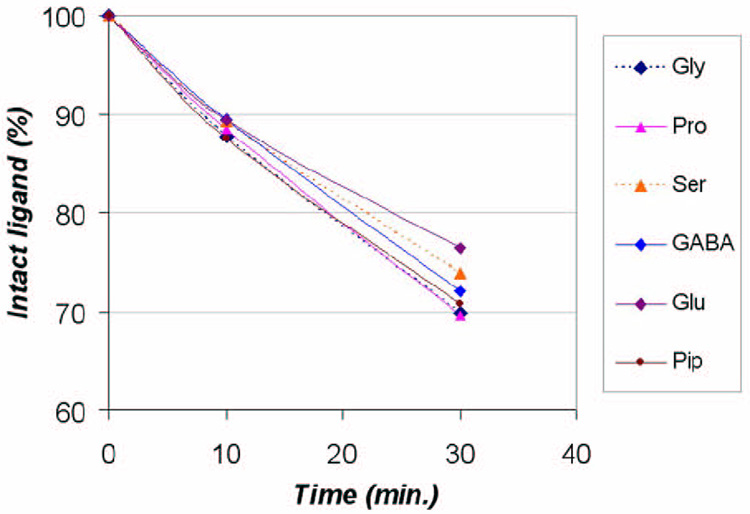

The stability of free photoligands was evaluated by an HPLC method, in which buffer solutions of free ligands were irradiated under UV and aliquots were taken at several time points to quantify the intact ligands by HPLC. As shown in Figure 5, approximately 70–77% of photoligands remained intact after 30 min irradiation under a UV-A lamp (λmax 350 nm). Decomposition of free 4 (Pro) was not significantly faster than others; in fact, it was almost identical to that of 1. Thus, decomposition of 4 could not account for the diminished photolabeling efficiency.

Figure 5.

Stability of photoligands under UV. Ligand solutions were irradiated under a UV-A lamp (λmax 350 nm). At different time points (0, 10, and 30 min), aliquots were taken and the amounts of intact ligand was quantified by HPLC (UV 280 nm). See the Methods and Materials section for more details.

3. Discussion

Target-binding is a prerequisite for photoaffinity-labeling and needs to be assessed before a newly synthesized photoligands are subjected to photocrosslinking experiments. Since benzophenone is a reversible photophore (i.e., benzophenone can be photoactivated multiple times until it undergoes photochemical reactions), it is generally believed that photolabeling by benzophenone reflects target-binding better than many other photocrosslinking agents, such as diazirine and azide; since diazirine and azide can be photoactivated only once, they are more susceptible to many factors that affects the kinetics of photochemical reaction, such as conformational flexibility. Many studies of benzophenone photoprobes describe preliminary biological data, such as Kd, Ki, and/or IC50, to show that the synthesized compounds bind to their intended targets.30–34 However, an important question that has not been addressed in existing literature is whether binding affinity is predictive of successful photolabeling experiments. A compound with high affinity could still fail to label target proteins. Conversely, a compound with low affinity could still be a good photolabeling agent. The current study indicates that binding affinity can misguide selection and optimization of benzophenone photophores. There was a clear discrepancy between IC50 and photolabeling efficiency of our Lck photoligands. Similar disagreements between binding affinity and photolabeling efficiency can also be seen in other studies.9, 15 Although existing papers usually do not delve into the photoprobes that failed to label target proteins, it is likely that similar observations have been made in many other studies. Clearly, binding affinity should not be the only criterion to select and optimize newly prepared benzophenone photoligands. In other words, benzophenone photoligands with diminished biological activity can be still useful if their specificity can be determined by appropriate control experiments, such as blocking of photolabeling with specific ligands of targets.

Our current finding is reminiscent of the studies on intramolecular photochemical reactions a few decades ago, which founded the basis of many important concepts in photochemistry.17,18,29 Those studies identified conformational mobility as a critical factor controling the rate of intramolecular benzophenone photochemistry; molecules need flexibility to attain stereoelectronic requirements for intramolecular hydrogen abstraction and radical recombination.1,35,36 After all, the photocrosslinking of Lck by a “bound” ligand is akin to intramolecular photochemical reactions. The high labeling efficiency of 6 (GABA) reflects the flexibility around benzophenone in the bound ligand, which permits a rapid photocrosslinking reaction. On the other hand, 4 (Pro) did not label Lck because of the conformational constraint on the backbone. In the case of compound 2 (Ser), hydrogen bond(s) with the Lck surface probably restricted the mobility of benzophenone in the bound ligand. Thus, the higher binding-affinity of 2 did not result in enhanced labeling efficiency.

Conformational flexibility has been recognized as an important parameter which can be tweaked to optimize benzophenone probes. In their review on benzophenone photophores, Dorman and Prestwich offer the following prescriptive advice: “BP (benzophenone) photochemistry in biochemical systems is most regioselective when the flexibility is limited to only that which is necessary to achieve efficient H-abstraction.”1 While regioselectivity is a particularly important issue when ligand-receptor interactions are studied in atomic details,16 efficiency of photolabeling is emphasized in other applications, including chemical proteomics.6–13 The shift in the emphasis, i.e., from regioselectivity to efficiency, can change the way conformational flexibility is modulated when new benzophenone photoprobes are designed. Higher conformational flexibility can dramatically increase the rate of photochemical reactions. Our current study also shows a striking improvement in labeling efficiency when two methylene carbons are inserted in the middle of our Lck photoligand. Thus, a slight increase of conformational flexibility is a reasonable option to improve benzophenone photoprobes in cases where regioselectivity/specificity is not the central concern.

Modulation of conformational flexibility can also affect the rate of intramolecular photochemical reactions. To address this concern, the current study examined the stability of our Lck photoligands under UV light. This additional HPLC study allowed us to eliminate the possibilities of undesired side-reactions, which, in turn, provided a clearer mechanistic picture. The stability of photoprobes under UV light is rarely discussed in other studies. However, it may be an important issue especially when the probes of interest have modest binding-affinity to targets.

4. Conclusions

The current SAR of our Lck photoligands provided a new insight into the relative importance of binding affinity and conformational flexibility. The study showed that binding-affinity did not foretell photolabeling efficiency of our Lck photoligands. Instead, conformational flexibility correlated with the labeling efficiency. A slight increase of conformational flexibility can be a simple strategy to improve labeling efficiency of benzophenone photoprobes, especially in the applications for chemical proteomics. It is our expectation that the increasing usage of benzophenone in chemical proteomics will generate further SAR data, which, in turn, will improve our ability to design and execute photoaffinity-labeling studies.

5. Experimental

5.1. Materials

Fmoc-Gly-Wang resin, Fmoc-protected amino acids, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) were purchased from Fluka. Biotin-N-hydroxysuccinimide was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The Fmoc-protected PNA-adenine monomer (Fmoc-PNA-adenine-(Bhoc)-OH) was purchased from Applied Biosystems. Laemmli sample buffer, Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer, and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate were purchased from BioRad. Lck was obtained from Invitrogen. ECL-Plus chemiluminescence reagent was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. Kinase-Glo® Plus Luminescent Kinase Assay kit was purchased from Promega. Src tyrosine kinase substrate was obtained from Biomol. Greiner Bio-One Lumitrac 384 well-plate (solid white) was purchased from VWR Scientific. 4-Amino-5-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-7H-pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-7-yl-cyclopentane (the ATP-competitive Lck inhibitor; Calbiochem) was purchased through VWR Scientific. All other chemicals and solvents were obtained through Fisher Scientific and used without further purification.

5.2. Physicochemical analyses

NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in δ units (ppm) using the solvent peak as the internal standard. 1H NMR splitting patterns are designated as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), doublet of doublet (dd), and doublet of triplet (dt). Splitting patterns that could not be interpreted or easily visualized are designated as multiplet (m).

Mass spectrometric data were acquired on an Agilent Technologies 1100 Series LC/MSD model G1946D using electrospray (ESI) ionization. Ionization was carried out with a drying gas temperature of 175 °C, a nebulizer pressure of 40 psi and a flow rate of 13 L/min. The mass range scanned was between 140 and 1000 amu. The capillary was set to 4000 volts. Samples were introduced into the mass spectrometer using a 1:1 mixture of water and acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid and 50 µM ammonium acetate. The flow rate of the solvent was 500 µl/min. Data was processed using Agilent's Chemstation software.

5.3. Synthesis of Lck photoligands

5.3.1. General

Synthesis was accomplished using the Fmoc-chemistry on solid phase as described previously.6, 24 The purified probes were characterized using analytical HPLC, mass spectrometry, and NMR. The NMR spectra exhibited conformational isomerism at room temperature, which arise from the tertiary amide conformers at the PNA-adenine moiety. The 1H-NMR data given below are for the major conformers of the probes.

5.3.2. Compound 1 (Gly ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.50 (1H, t, NH), 8.42 (1H, m, NH), 8.29 (1H, s, CH), 8.25 (1H, s, CH), 8.04 (1H, m, NH), 7.70-7.22 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.30 (2H, s, NH2), 6.35 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.25 (2H, m, CH2), 4.65 (1H, m, CH), 4.32 (1H, m, CH), 4.20 (2H, m, CH2), 4.15 (1H, m, CH), 3.70 (2H, m, CH2), 3.60 (2H, m CH2), 3.40 (2H, m, CH2), 3.29 (2H, m, CH2), 3.20 (2H, t, CH2), 3.10 (2H, m, CH2), 2.90 (1H, m, CH) 2.75 (2H, m, CH2), 2.19-2.17 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 1.82 (2H, m, CH2), 1.10–1.55 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 971.07 [M+H]+, 993.06 [M+Na]+, 486.03 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 19.01 min.

5.3.3. Compound 2 (Pro ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.60 (1H, t, NH), 8.45 (1H, m, NH), 8.40 (1H, s, CH), 8.35 (1H, s, CH), 8.15 (1H, m, NH), 7.65-7.20 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.20 (2H, s, NH2), 6.35 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.48 (2H, m, CH2), 4.52 (1H, m, CH), 4.32 (1H, m, CH), 4.24 (1H, t, CH), 4.10 (1H, m, CH), 3.70 (2H, m, CH2), 3.65 (2H, m CH2), 3.38–3.47 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 3.20 (2H, m, CH2), 3.16 (2H, m, CH2), 3.10 (2H, m, CH2), 2.80 (1H, m, CH) 2.75 (2H, m, CH2), 2.15-2.05 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 1.18 (2H, m, CH2), 1.75(2H, m, CH2), 1.45–1.55 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 1.10–1.34 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 1025.16 [M+H]+, 513.58 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 20.15 min.

5.3.4. Compound 3 (Pip ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.65 (1H, t, NH), 8.50 (1H, m, NH), 8.39 (1H, s, CH), 8.30 (1H, s, CH), 8.10 (1H, m, NH), 7.70-7.20 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.25 (2H, s, NH2), 6.30 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.40 (2H, m, CH2), 4.60 (1H, m, CH), 4.30 (1H, m, CH), 4.24 (1H, t, CH), 4.15 (1H, m, CH), 3.75 (2H, m, CH2), 3.60 (2H, m CH2), 3.35–3.45 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 3.29 (2H, m, CH2), 3.24 (2H, t, CH2), 3.15 (2H, m, CH2), 2.90 (1H, m, CH) 2.80 (2H, m, CH2), 2.19-2.17 (6H, m, 3×CH2), 1.19 (2H, m, CH2), 1.80 (2H, m, CH2), 1.15–1.50 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 1011.11 [M+H]+, 506.55 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 20.05 min.

5.3.5. Compound 4 (Ser ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.64 (1H, t, NH), 8.48 (1H, m, NH), 8.25 (1H, s, CH), 8.20 (1H, s, CH), 8.04 (1H, m, NH), 7.75-7.20 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.30 (2H, s, NH2), 6.37 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.20 (2H, m, CH2), 4.55 (1H, m, CH), 4.40 (1H, m, CH), 4.32 (1H, m, CH), 4.18 (2H, m, CH2), 4.15 (1H, m, CH), 3.75 (2H, m, CH2), 3.62 (2H, m CH2), 3.44 (2H, m, CH2), 3.26 (2H, m, CH2), 3.20 (2H, t, CH2), 3.08 (2H, m, CH2), 2.90 (1H, m, CH) 2.75 (2H, m, CH2), 2.30-2.20 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 2.04 (1H, t, OH), 1.80 (2H, m, CH2), 1.15–1.60 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 1002.00 [M+H]+, 501.03 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 16.05 min.

5.3.6. Compound 5 (Glu ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.45 (1H, t, NH), 8.42 (1H, m, NH), 8.30 (1H, s, CH), 8.23 (1H, s, CH), 8.10 (1H, m, NH), 7.70-7.20 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.27 (2H, s, NH2), 6.30 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.25 (2H, m, CH2), 4.75 (1H, m, CH), 4.60 (1H, m, CH), 4.42 (1H, m, CH), 4.25 (1H, m, CH), 3.75 (2H, m, CH2), 3.60 (2H, m CH2), 3.54 (2H, m, CH2), 3.36 (2H, m, CH2), 3.22 (2H, t, CH2), 3.10 (2H, m, CH2), 2.80 (1H, m, CH) 2.65 (2H, m, CH2), 2.47-2.35 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 2.30-2.17 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 1.82 (2H, m, CH2), 1.20–1.60 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 1043.23 [M+H]+, 522.06 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 16.10 min.

5.3.7. Compound 6 (GABA ligand)

1H-NMR δ ppm (500MHz, DMSO) 8.55 (1H, t, NH), 8.45 (1H, m, NH), 8.30 (1H, s, CH), 8.20 (1H, s, CH), 8.14 (1H, m, NH), 7.70-7.20 (9H, m, 9×CH), 7.20 (2H, s, NH2), 6.25 (2H, m, 2×NH), 5.20 (2H, m, CH2), 4.62 (1H, m, CH), 4.31 (1H, m, CH), 4.15 (2H, m, CH2), 4.10 (1H, m, CH), 3.74 (2H, m, CH2), 3.60 (2H, m CH2), 3.45 (2H, m, CH2), 3.30 (2H, m, CH2), 3.25-3.18 (4H, m, 2×CH2), 3.15 (2H, m, CH2), 2.95 (1H, m, CH) 2.70 (2H, m, CH2), 2.20-2.10 (8H, m, 4×CH2), 1.80 (2H, m, CH2), 1.15–1.55 (6H, m, CH2CH2CH2). ESIMS m/z 999.12 [M+H]+, 1021.10 [M+Na]+, 500.04 [M+2H]2+. tR (analytical): 19.25 min.

5.4. Lck kinase assay

The inhibitory activities of individual photoligands were determined using Kinase-Glo® Plus Luminescent Kinase Assay (Promega). This assay utilizes luciferase to monitor unused ATP in kinase reactions; thus the signal is high when kinase is inhibited. Assays were performed per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 8 µl of 0.25mM Src substrate peptide (Biomol) in a buffer (50 mM HEPES pH7.3, 2.5 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2) was added to each well of 384 well plate (Greiner Bio-One Lumitrac plate, solid white). 0.5 µl of Lck (Invitrogen, Part# P3043, Lot# 37621F), which had been prediluted in the buffer above to 46 ng/µl, and 0.5 µl of ligand at different concentrations were then added to each well. Kinase reaction was initiated by 1 µl of 100 µM ATP. After 1 hour incubation at the room temperature, 10 µl of Kinase-Glo reagent was added to each well and incubated further for 10 min at room temperature. Luminescence of each well was measured by SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices). IC50 values and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of a mean were obtained by fitting the data from replicate trials (n = 2 or 3) to a sigmoidal dose-response curve using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

5.5. Photolabeling of Lck and Western blot

Photolabeling and Western blot was carried out using a reported protocol6, 24 with a minor modification. Specifically, after the blocking of the blotted PVDF membrane, streptavidin-HRP conjugate (1:10,000 dilution in 3% non-fat milk in TBS-T) was used to visualize the biotinylated Lck. Bands were observed and quantified with the BioRad ChemiDoc gel documentation system. In band quantitation, background signal, which defined the 0% labeling, was subtracted from each band. The 100% labeling was defined as the maximum band intensity obtained with the highest concentration (180 µM) of compound 1 (Gly).

The photocrosslinking efficiency was assessed by measuring EC50. To this end, the dose-labelling relationship was first obtained by labelling Lck with different concentrations of each compound (0, 3, 9, 18, 36, 90, 180 µM). Intensities of the observed bands were plotted against probe concentration. EC50 values and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of a mean were obtained by fitting the data from triplicate trials (n = 3) to a sigmoidal dose-response curve using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

5.6. Measurement of probe decomposition under UV

The decomposition of probes under UV irradiation was monitored by RP-HPLC. 100 µl of each probe (30 µM) in the buffer was irradiated under six Sylvania 350 Blacklight lamps (15 W, λmax 350 nm), in which samples were kept on ice and placed approximately 5 cm below the lamps. At various time intervals (t = 0, 10, and 30 min), aliquots were taken and examined by HPLC. Peak areas on chromatograms were used to estimate the intact probe concentrations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:xxxxxxxxx

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by PSC-CUNY Grant (PSCREG-37-813). RR-03037 from NCRR/NIH, which supports the research infrastructure at Hunter College, is also acknowledged. L.J. thanks fellowship support from the MARC program (GM007823) at Hunter College. We thank Mr. Kwang Won Cha for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5661. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prestwich GD, Dorman G, Elliott JT, Marecak DM, Chaudhary A. Photochem. Photobiol. 1997;65:222. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kale TA, Hsieh SA, Rose MW, Distefano MD. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003;3:1043. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chorev M. Receptors Channels. 2002;8:219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawamura A, Hindi S. Chirality. 2005;17:332. doi: 10.1002/chir.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourot A, Grutter T, Goeldner M, Kotzyba-Hibert F. Chembiochem. 2006;7:570. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uttamchandani M, Li J, Sun H, Yao SQ. Chembiochem. 2008;9:667. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salisbury CM, Cravatt BF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2184. doi: 10.1021/ja074138u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salisbury CM, Cravatt BF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieber SA, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Cravatt BF. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:274. doi: 10.1038/nchembio781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saghatelian A, Jessani N, Joseph A, Humphrey M, Cravatt BF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:10000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402784101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan EW, Chattopadhaya S, Panicker RC, Huang X, Yao SQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14435. doi: 10.1021/ja047044i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry LK, Khare S, Son C, Babu VVS, Naider F, Becker JM. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6128. doi: 10.1021/bi015863z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong M, Li Z, Pinon DI, Lybrand TP, Miller LJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittelsberger A, Mierke DF, Rosenblatt M. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2008;71:380. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winnik MA. Chem. Rev. 1981;81:491. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1983;16:461. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina TJ, Kishihara K, Siderovski DP, van Ewijk W, Narendran A, Timms E, Wakeham A, Paige CJ, Hartmann KU, Veillette A, et al. Nature. 1992;357:161. doi: 10.1038/357161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson SJ, Levin SD, Perlmutter RM. Nature. 1993;365:552. doi: 10.1038/365552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palacios EH, Weiss A. Oncogene. 2004;23:7990. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman FD, Ballas ZK, Schutte BC, Kemp J, Hollenback C, Noraz N, Taylor N. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:421. doi: 10.1172/JCI3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marth JD, Overell RW, Meier KE, Krebs EG, Perlmutter RM. Nature. 1988;332:171. doi: 10.1038/332171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hindi S, Deng H, James L, Kawamura A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:5625. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koresawa M, Okabe T. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2004;2:153. doi: 10.1089/154065804323056495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2385. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold LD, Calderwood DJ, Dixon RW, Johnston DN, Kamens JS, Munschauer R, Rafferty P, Ratnofsky SE. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:2167. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00441-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burchat AF, Calderwood DJ, Hirst GC, Holman NJ, Johnston DN, Munschauer R, Rafferty P, Tometzki GB. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:2171. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winnik MA. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977;10:173. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qvit N, Monderer-Rothkof G, Ido A, Shalev DE, Amster-Choder O, Gilon C. Peptide Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1002/bip.21010. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeGraw AJ, Zhao Z, Strickland CL, Taban AH, Hsieh J, Jefferies M, Xie W, Shintani DK, McMahan CM, Cornish K, Distefano MD. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4587. doi: 10.1021/jo0623033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato E, Howitt R, Dzyuba SV, Nakanishi K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:3758. doi: 10.1039/b713333b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuwa H, Hiromoto K, Takahashi Y, Yokoshima S, Kan T, Fukuyama T, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Natsugari H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:4184. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen R, Inoue T, Forgac M, Porco JA., Jr J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3686. doi: 10.1021/jo0477751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Severance D, Pandey B, Morrison H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3231. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner PJ, Pabon R, Park B-S, Zand AR, Ward DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:589. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:xxxxxxxxx