Abstract

Background and Purpose

Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a major contributor to mortality and morbidity following aneurysm rupture. Recently, R-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) expression has been associated with increased cerebral artery constriction in a rabbit model of SAH. The goal of the present study was to examine whether the blood component oxyhemoglobin (oxyHb) can mimic the ability of SAH to cause R-type VDCC expression in the cerebral vasculature.

Methods

Rabbit cerebral arteries were organ cultured in serum-free media for up to five days in the presence or absence of purified oxyHb (10 μmol/L). Diameter changes in response to diltiazem, (L-type VDCC antagonist) and SNX-482 (R-type VDCC antagonist) were recorded at day 1, 3, or 5 in arteries constricted by elevated extracellular potassium. RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from arteries cultured for 5 days (± oxyHb) to assess VDCC expression.

Results

After five days, oxyHb-treated arteries were less sensitive and partially resistant to diltiazem compared to similar arteries organ cultured in the absence of oxyHb. Further, SNX-482 dilated arteries organ cultured for five days in the presence, but not in the absence, of oxyHb. RT-PCR revealed that oxyHb treated arteries expressed R-type VDCCs (Cav 2.3) in addition to L-type VDCCs (Cav 1.2), whereas untreated arteries expressed only Cav 1.2.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that oxyhemoglobin exposure for 5 days induces the expression of Cav 2.3 in cerebral arteries. We propose that oxyhemoglobin contributes to enhanced cerebral artery constriction following SAH via the emergence of R-type VDCCs.

Keywords: Calcium channels, Cerebral arteries, Subarachnoid hemorrhage, Vasospasm, Vascular Smooth Muscle

Introduction

Oxyhemoglobin (oxyHb) has been implicated in the development of cerebral vasospasm and the associated delayed neurological deficits frequently encountered following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). For example, the peak in free oxyHb concentrations in the cerebral spinal fluid of SAH patients, due to lysis of red blood cells, correlates with the onset of cerebral vasospasm following aneurysm rupture1. Further, in vivo application of oxyHb into the subarachnoid space can mimic the effect of whole blood to induce cerebral vasospasm2. Although evidence suggests oxyHb contributes to the development of SAH-induced vasospasm, the mechanisms involved in this phenomenon are less clear.

Acute application of oxyHb constricts cerebral arteries via a number of mechanisms including suppression of K+ channel activity, enhanced calcium entry and increased activity of protein kinase C and Rho kinase3-9. Currently, it is uncertain whether altered gene expression may also contribute to the ability of oxyHb to decrease cerebral artery diameter. Our laboratory has recently shown expression of R-type VDCCs, encoded by the gene Cav 2.3, in small diameter cerebral arteries in a rabbit model of SAH10. The emergence of R-type VDCCs in cerebral artery myocytes, combined with existing L-type VDCCs, would promote elevated intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and ultimately increased cerebral artery constriction.

The objective of the present study was to examine whether purified oxyHb mimics SAH to induce Cav 2.3 expression in the cerebral vasculature. Here, we report the emergence of R-type VDCCs in cerebral arteries from healthy rabbits organ cultured in the presence of purified oxyHb for a period of five days. Further, our data suggest that L-type VDCCs in cerebral arteries become less sensitive to antagonists such as diltiazem following 5 day exposure to oxyHb. These findings are consistent with a role of oxyHb-induced R-type VDCC expression in enhanced constriction of small diameter cerebral arteries following SAH.

Materials and Methods

All protocols were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Vermont. New Zealand White rabbits (male, 3.0 - 3.5 kg) were euthanized by exsanguination under deep pentobarbital anesthesia (IV; 60 mg/kg). Cerebral arteries were dissected in ice cold MOPS solution containing 1% BSA with the following composition (in mmol/L): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl , 1 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1 KH2PO4, 0.02 EDTA, 2 pyruvate, 5 glucose, 3 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7.4.

Organ culture of cerebral arteries

Once blood was flushed from the lumen, anterior and posterior cerebral arteries were transferred into serum free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 supplemented with penicillin (50 U/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) and placed in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 97% humidity. Arteries were cultured for up to five days in the presence or absence of purified hemoglobin Ao (oxy form; 10 μmol/L, Hemosol Inc., Toronto, Canada)(oxyHb). Culture medium was changed twice daily to maintain oxyHb levels, as our spectrophotometric studies indicate that oxyHb concentrations decreased approximately 20% after 8 hrs in organ culture (data not shown). A concentration of 10 μmol/L oxyHb was chosen to approximate extravascular levels of this compound reported near cerebral arteries following SAH1. Preliminary studies were also performed using arteries organ cultured with a higher concentration (100 μmol/L) of oxyhemoglobin. However, we observed a dramatic decrease in the viability of arteries organ cultured with 100 μmol/L Oxyhb for a period of 5 days (5 out of 5 arteries from 3 different animals).

Diameter measurements in isolated arteries

Isolated arteries were cannulated in a 5-ml myograph chamber (Living Systems Instruments, Burlington, VT) and perfused with aerated physiological saline solution (PSS) with the following composition (in mmol/L): 118.5 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.18 KH2PO4, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 0.023 EDTA, and 11 glucose, pH 7.4) at 37 °C, as previously described 11. Arteries were discarded if an initial constriction representing less than a 40% decrease in diameter to 60 mmol/L K+ PSS (iso-osmotic replacement of NaCl with KCl) was observed. To explore VDCC function, isolated arteries were constricted by increasing extracellular K+ from 6 mmol/L to 60mmol/L, shifting the K+ equilibrium potential (EK) from approximately -85 mV to approximately -20 mV. In cerebral artery myocytes, the membrane potential depolarization accompanying this positive shift in EK leads to an increase in the open-state probability of VDCCs, an increase in the concentration of free intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), and vasoconstriction12,13. To selectively study VDCC function, arteries were held at a relatively low intravascular pressure (20 mmHg) to minimize activation of mechanosensitive cation channels and other cell signaling pathways such as protein kinase C14. Cumulative concentration-response curves to the L-type VDCC blocker diltiazem15 were obtained from arteries constricted with 60 mmol/L K+ PSS at an intravascular pressure of 20 mmHg. Dilations to the R-type VDCC blocker SNX-482 (200 nmol/L)16 were obtained from arteries constricted with 60 mmol/L K+ PSS in the presence and absence of diltiazem. Responses to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine and the nitrovasodilator sodium nitroprusside were examined in arteries constricted by a combination of histamine (30 μmol/L) and serotonin (30 μmol/L) at an intravascular pressure of 60 mmHg. Oxyhemoglobin was not included in the PSS during diameter measurements in isolated cerebral arteries.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from freshly isolated and organ cultured cerebral arteries and brain using RNeasy Micro kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized by Omniscript reverse transcriptase (QIAGEN) using 250 ng of total RNA. Reactions were also performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase as a negative control, using an equal amount of total RNA. A unique coding region of the R-type VDCC α1 subunit (α1E; Cav 2.3 GenBank Accession # X67855) was amplified using the following set of primers: sense nucleotides 6562-6580 (5’-GAGCAGCGACAACACCTAC-3’) and antisense nucleotides 6996-6978 (5’-GCTGGTGGAGAGAAGTTGC-3’). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed by comparing band intensities of arteries organ cultured in the absence and presence of oxyHb when equivalent amounts of cDNA were used for each preparation as determined by GAPDH PCR amplification. To further verify expression of Cav 2.3, nested PCR was used with the following sets of primers: forward primer 5’-ACCCCTCGTCCTGT CCTCAC-3’ (3586-3605) and reverse primer 5’-TGCTCTCGGTGGTGACCTTG-3’ (3773-3754) for the 1st round PCR; 5’-CGAGGGTGTGGGGAAAGAG-3’ (3607-3625) and 5’-CGGTGGTGACCTTGTCTGTG-3’ (3767-3748) for the 2nd round PCR. The amplified DNA was extracted from gel bands and sequenced to confirm PCR products.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was considered at the level of p < 0.05 (*) or p < 0.01 (**) using Student’s t-test for comparisons between two groups or analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test for pairwise multiple comparisons.

Results

Five day oxyhemoglobin exposure reduces the efficacy of the L-type VDCC blocker diltiazem to dilate cerebral arteries

Our initial goal was to examine the impact of 1-5 day oxyHb exposure on VDCC function in small diameter cerebral arteries. Increasing extracellular K+ to 60 mmol/L caused freshly isolated cerebral arteries to constrict by 113 ± 12 μm, representing a 59 % decrease in diameter (n = 5). In the presence of 60 mmol/L K+, the L type VDCC blocker diltiazem evoked a concentration-dependent dilation of freshly isolated cerebral arteries, causing a maximum dilation of 98.8 ± 0.4 percent at a concentration of 1 mmol/L (Figure 1a). To explore the influence of oxyHb on VDCC function, cerebral arteries were placed in serum-free organ culture media in the presence or absence of purified oxyHb (10 μmol/L) for a period of one to five days. Following organ culture, arteries were removed from the media, placed in PSS (in the absence of oxyHb), and canulated for in vitro diameter measurements. Following a 30 min equilibration period, in vitro arterial diameters in PSS were not significantly different between organ cultured and freshly isolated arteries (Table 1). As with freshly isolated arteries, diltiazem (1 mmol/L) fully dilated arteries organ cultured for 24 or 72 hours (± oxyHb) that were constricted with 60 mmol/L extracellular K+ (Figure 1a, b). The IC50 values for diltiazem-induced dilation were not significantly different (approximately 1 μmol/L, Table 1) in freshly isolated arteries and arteries organ cultured for 24 or 72 hours (± oxyHb). However, after 5 days of organ culture, a marked difference emerged between arteries maintained in the presence and absence of oxyHb. K+-induced constrictions from arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence of oxyHb were significantly less sensitive to diltiazem as evidenced by a greater than 10-fold increase in the IC50 value (16. 9 ±6.9 μmol/L). Further, approximately 20% of the K+-induced constriction in these arteries was resistant to 1 mmol/L diltiazem, a concentration nearly 1000-fold higher than the IC50 for freshly isolated arteries (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves to the L-type VDCC blocker. Extracellular K+ was increased to 60 mmol/L (maximum constriction) prior to addition of increasing concentrations of diltiazem. a) Freshly isolated and arteries organ cultured for 24 hours (± oxyHb, 10 μmol/L). b) Arteries organ cultured for 72 hours (± oxyHb). c) arteries organ cultured for 96 hours (± oxyHb). Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 4-7. * p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, students t-test.

TABLE 1.

Diltiazem-induced dilation of fresh and organ cultured cerebral arteries.

| Day 0 (n=5) | Day1 | Day3 | Day5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - oxyHb (n=5) | + oxyHb (n=6) | - oxyHb (n=7) | + oxyHb (n=5) | - oxyHb (n=4) | + oxyHb (n=5) | ||

| Arterial diameter at 20 mmHg (μm)§ | 192.6±24.0 | 258.6±25.7 | 259.5±20.1 | 215.1±17.5 | 257.6±20.6 | 212.3±26.4 | 184.0±17.0 |

| K+-induced constriction (% decrease in diameter)§ | 59.0±1.4 | 57.9±3.9 | 58.9±3.0 | 59.0±1.0 | 61.2± 2.9 | 57.7±3.1 | 62.4±1.8 |

| Diltiazem IC50 (μmol/L) | 0.93±0.06 | 0.76±0.07 | 0.95±0.14 | 0.78±0.12 | 1.07±0.06 | 1.1±0.10 | 16. 9±6. 9 * |

| Diltiazem max dilation (% passive diameter) | 98.8±0.4 | 99.5±0.5 | 99.0±0.2 | 99.3±0.3 | 98.6±0.4 | 98.3±0.6 | 80.7±1. 3 * |

p<0.05, Analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test for pairwise multiple comparisons.

The power of the performed test was below the desired power of 0.800. The lack of statistical difference should be interpreted cautiously.

We next examined whether organ culture of arteries for 5 days affected responses to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (Ach) or the endothelium-independent nitrovasodilator sodium nitroprusside (SNP). As Ach and SNP may act in part through K+ channel activation 17, arteries were constricted with a combination of histamine and serotonin, rather than with 60 mmol/L K+. Ach-induced dilations were significantly reduced in arteries organ cultured for 5 days compared to freshly isolated arteries (Figure 2b). However, no significant differences were observed in Ach-induced dilations in arteries cultured for 5 days in the absence compared to the presence of oxyHb. In contrast to Ach responses, SNP-induced dilations were similar in freshly isolated arteries and arteries organ cultured in the absence and presence of oxyHb (Figure 2c). Thus, although organ culture of arteries may lead to a decrease in endothelial cell viability, inclusion of oxyHb in the organ culture media did not per se alter Ach-induced vasodilation. Further, responses to the exogenous nitrovasodilator, SNP, were not altered by organ culture or oxyHb treatment. These data suggest that the decreased efficacy of diltiazem to dilate arteries organ cultured in the presence of oxyHb reflects a selective and fundamental change in VDCCs of cerebral artery myocytes.

Figure 2.

Endothelium-dependent and –independent dilation of cerebral arteries organ cultured in the presence and absence of oxyHb. Arteries were constricted with a combination of histamine (30 μmol/L) and serotonin (30 μmol/L) prior to addition of increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (Ach) (panel a) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (panel b). Day 0 represents freshly isolated cerebral arteries. ** p < 0.01, Day 0 versus Day 5 (± oxyHb). In many cases, where no statistical differences were observed, the power of the performed test was below the desired power of 0.800. The lack of statistical difference should be interpreted cautiously.

The R-type VDCC blocker SNX-482 dilates cerebral arteries following 5-day exposure to oxyhemoglobin

The above data demonstrates that K+-induced constriction of cerebral arteries exposed to oxyHb for 5 days is partially resistant to the L-type VDCC blocker diltiazem. We have previously reported a similar phenomenon due to the emergence of R-type VDCCs in cerebral arteries obtained from a rabbit model of subarachnoid hemorrhage10. We next examined whether diltiazem-resistant constrictions observed following 5-day oxyHb treatment could be reversed by SNX-482, a blocker of R-type VDCCs 16. In arteries treated with oxyHb for a period of 5 days, diltiazem (1 mmol/L) dilated K+-constricted arteries by 83.2 ± 3.1 percent, and subsequent addition of SNX-482 (200 nmol/L) caused a further dilation of these arteries to their maximum diameter. Thus, the combination of diltiazem and SNX-482 caused a complete reversal of K+-induced constriction in oxyHb-treated arteries, similar to the effects of diltiazem alone in untreated organ cultured arteries (figure 3a). In the absence of diltiazem, SNX-482 significantly dilated arteries treated with oxyHb for five days (33.5 ± 4.7 μm, n = 4), but did not significantly alter the diameter of arteries organ cultured for a similar period in the absence of oxyHb (figure 3b). As predicted, SXNX-482 did not dilate arteries exposed to oxyHb for shorter periods of time (1 or 3 days, n = 3, data not shown). These results indicate the functional presence of R-type VDCCs in small diameter cerebral arteries treated with oxyHb for 5 days whereas arteries organ cultured for a similar period in the absence of oxyHb have a single population of diltiazem-sensitive L-type VDCCs.

Figure 3.

The R-type VDCC blocker, SNX-482, dilates arteries following 5 day organ culture in the presence of oxyHb. a) Diltiazem (Dilt, 1 mmol/L) caused maximal dilation of arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the absence of oxyHb (n = 4). However, in arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence of oxyHb, K+-induced constrictions were partially resistant to diltiazem (n = 5). SNX-482 (200 nmol/L) abolished these diltazem-resistant constrictions. ** p< 0.001, using Student-Newman-Keuls pairwise multiple comparison method. b) SNX-482 dilated arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence, but not absence of oxyHb. * p< 0.05, students t-test, n =4. In many cases, where no statistical differences were observed, the power of the performed test was below the desired power of 0.800. The lack of statistical difference should be interpreted cautiously

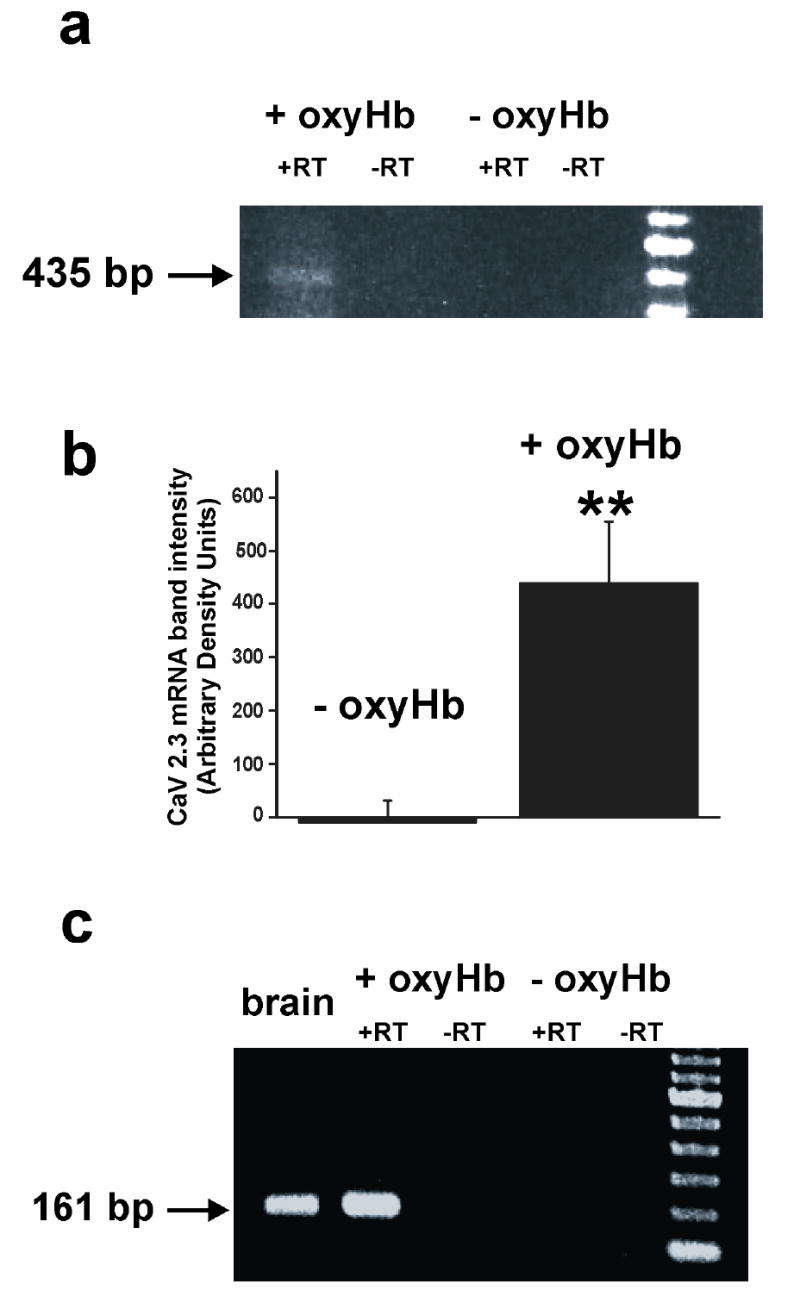

Oxyhemoglobin increases expression of R-type VDCCs in cerebral arteries

To further examine the ability of oxyHb to increase R-type VDCCs in cerebral arteries, RT-PCR was used to determine mRNA levels of Cav 2.3, the gene encoding the pore-forming α1 subunit of R-type VDCCs. In the absence of oxyHb, Cav 2.3 mRNA was not detected in arteries cultured for 5 days (n = 5). However, following 5 day treatment with oxyHb, Cav 2.3 mRNA was observed in 3 out of 5 preparations, although the intensities of these bands were relatively faint (figure 4a). RT-PCR studies were repeated on arteries obtained from an additional 6 animals. In this second RT-PCR series, semi-quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in Cav 2.3 mRNA levels in samples organ cultured in the presence compared to the absence of oxyHb (figure 4b). To confirm the selective expression of Cav 2.3 in arteries cultured in the presence of oxyHb, we performed nested PCR. Nested PCR is a highly sensitive method to detect low levels of gene expression by utilizing two rounds of PCR. Here, the first round PCR product, as amplified using primers targeting a region that is unique to Cav 2.3, was employed as a template for the second round of PCR. Using nested PCR, expression of R-type Ca2+ channels after 5 day treatment with oxyHb was clearly seen in five out of five preparations examined (figure 4b). In arteries organ cultured in the absence of oxyHb, a PCR band corresponding to Cav 2.3, was observed one out of five samples. DNA analysis confirmed that the sequence of these bands matched the Cav 2.3 sequence in published database (GenBank Accession number X 67855). These results demonstrate that organ culture of arteries with oxyHb induces R-type VDCC gene expression.

Figure 4.

Cav 2.3 expression in cerebral arteries following 5 day organ culture in the presence of oxyHb. a) RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for the R-type VDCC (Cav 2.3). The expected 435 bp product (arrow) was detected using 250 ng of total RNA extracted from cerebral arteries from arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence (+ oxyHb), but not absence of oxyhemoglobin (- oxyHb). b) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed by comparing band intensities using equivalent amounts of cDNA (n = 6). c) Nested RT-PCR was performed using primers encoding a sequence unique to Cav 2.3.

Discussion

Here we provide evidence that oxyhemoglobin can induce R-type VDCC expression in small diameter cerebral arteries. We report that arteries organ cultured for a period of 5 days in the presence of oxyHb exhibit constrictions that were partially resistant to the L-type VDCC antagonist, diltiazem. This diltiazem-resistant constriction was abolished by SNX-482, a blocker of R-type VDCCs. In contrast, diltiazem completely dilated freshly isolated arteries or arteries organ cultured in the absence of oxyHb, and SNX-482 was without effect. Consistent with functional observations, mRNA encoding R-type VDCCs (Cav 2.3) was detected in arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence, but not in the absence of oxyHb. These observations suggest that cerebral arteries typically contain L-type VDCCs, but prolonged exposure (5 days) to oxyHb can induce R-type VDCC expression that may contribute to cerebral artery constriction. Further, we report that L-type VDCCs become less sensitive to diltiazem following 5 day exposure to oxyHb.

The present work is consistent with our recent observations of the emergence of R-type VDCCs in small diameter cerebral arteries of a rabbit SAH model five days following the intracisternal injection of whole blood10. In cerebral arteries from SAH rabbits, R-type VDCC expression was associated with enhanced VDCC membrane currents and increased constriction at physiological intravascular pressures10. The present study suggests oxyHb, a major blood component, is the causative agent leading to the emergence of R-type VDCCs in cerebral artery myocytes following SAH. OxyHb-induced expression of R-type VDCCs would promote increased Ca2+ entry and enhanced constriction of cerebral arteries. We estimate, based on our present and past studies, that R-type VDCC expression caused by SAH or oxyhemoglobin is responsible for approximately 20 % of the constriction in response to elevated extracellular K+ or increased intravascular pressure. Considering flow through a cylinder is a function of the radius to the fourth power (Poiseuille’s Law), we believe R-type VDCC expression could have a substantial impact on cerebral blood flow following SAH. It is interesting to note that dilations to SNX-482 were slightly larger in the absence of diltiazem compared to in the presence of diltiazem in arteries organ cultured for five days in the presence of oxyHb (figure 3). Considering that SNX-482 had little, if any, effect in freshly isolated arteries, or arteries organ cultured in the absence of oxyHb, it is unlikely that 200 μmol/L SNX-482 is blocking L-type VDCCs. However, it is possible that the high concentration of diltiazem used in the present study (1mmol/L) may be influencing R-type VDCC activity or that there may be some unknown interaction between R-type and L-type VDCCs.

Numerous reports have provided evidence suggesting oxyHb plays a role in the development of SAH-induced vasospasm6,8,18,19. An action commonly attributed to oxyHb is vasoconstriction occurring shortly upon exposure of this agent to cerebral arteries in vitro3,4,9,20. Several mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to this acute oxyHb-induced contraction including Kv channel suppression3,5, inhibition of Ca2+ sparks4, elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels8,20,21, increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus due to increased activity of Rho kinase and/or protein kinase C9,22, decrease availability of nitric oxide23 and increased synthesis of the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE24. In the present study, arteries were organ cultured with oxyHb, however, oxyHb was not included in the physiological saline solution used during functional assessment following the organ culture period. Thus, our present findings suggest that in addition to the acute effects detailed above, long-term (5 day) oxyHb can impact cerebral artery function via changes in VDCC expression. It should be noted that the observed changes in CaV2.3 expression cannot be simply attributed to the organ culture conditions used in the present study. Firstly, a large body of previous work supports the approach of organ culturing intact artery segments in serum-free media11,25-28. Secondly, in the present study, cerebral arteries organ cultured in the absence of oxyHb exhibit properties comparable to freshly isolated arteries (e.g. figures 1 &2). Although organ culture conditions clearly do not exactly replicate in vivo conditions, we believe the approach used in the current study has allowed us to examine whether oxyHb can induce CaV2.3 expression in contractile cerebral artery myocytes. Considering that multiple cell types are present in intact cerebral arteries, it is, however, possible that cells other than vascular smooth muscle may contribute to the observed increased in Cav 2.3 mRNA levels following 5-day oxyHb exposure. Although we can not definitively rule out this possibility, functional data within this manuscript supports the notion that expression of Cav 2.3 occurs primarily in cerebral artery myocytes following oxyHb exposure.

At present, the signaling pathway linking oxyHb to Cav 2.3 expression in cerebral arteries is unclear. However, reactive oxygen species (ROSs), produced during the oxidation of oxyHb can regulate gene expression29, and may play a role in the pathogenesis of cerebral vasospasm23. Further, Peiro et al.30 have demonstrated that glycosylated human oxyHb leads to the activation of two transcription factors, nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1), in cultured human aortic smooth muscle via redox-sensitive pathways. Interestingly, activated NFκB has also been detected in cerebral cortices of a mouse SAH model in wild-type, but not super-oxide dismutase overexpressing mice31. Additionally, oxyHb-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i, could lead to the activation of Ca2+-dependent transcription factors such as cyclic-AMP dependent response element binding protein (CREB)32,33 and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (N-FAT)34. Future studies are needed to determine the transcriptional events associated with oxyHb-induced R-type VDCC expression.

In addition to enhanced expression of R-type VDCCs, 5 day exposure to oxyHb caused a decrease in the sensitivity of cerebral arteries to the L-type VDCC antagonist diltiazem. The IC50 value of diltiazem to reverse K+-induced constriction was 10-fold higher in arteries organ cultured for 5 days in the presence, compared to the absence of oxyHb (figure 1). This action of oxyHb is similar to the decreased functional response to L-type VDCC blockers reported by others following SAH35,36 or oxyHb incubation37. We have also demonstrated that VDCC membrane currents obtained from cerebral artery myocytes isolated from 5 day SAH rabbits were less sensitive to diltiazem and nisoldipine10. These findings may help to explain why L-type VDCC antagonists are potent dilators of arteries from healthy individuals, yet exhibit only modest efficacy in the improvement of clinical outcome in SAH patients.

In summary, here we have demonstrated that oxyHb can induce R-type VDCC gene expression and decrease the sensitivity of cerebral arteries to the L-type VDCC antagonist diltiazem. We propose that oxyHb-induced changes in VDCCs are likely to play an important role in diameter regulation in cerebral arteries following SAH.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hemosol Inc. for their gracious gift of the purified oxyhemoglobin used in this study. The authors also thank Drs. Masanori Ishiguro and Masayo Koide for their helpful comments on this study. This work was supported by the Totman Medical Research Trust Fund, the Peter Martin Brain Aneurysm Endowment, the American Heart Association (SDG # 003029N) and the NIH (NCRR, P20 RR16435 and NHLBI, R01 HL078983).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript that was accepted for publication in Stroke, copyright The American Heart Association. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, title 17, U.S. Code) without prior permission of the copyright owner, The American Heart Association. The final copyedited article, which is the version of record, can be found at Stroke. The American Heart Association disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties.

References

- 1.Pluta RM, Afshar JK, Boock RJ, Oldfield EH. Temporal changes in perivascular concentrations of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:557–561. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayberg MR, Okada T, Bark DH. The role of hemoglobin in arterial narrowing after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:634–640. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.4.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishiguro M, Morielli AD, Zvarova K, Tranmer BI, Penar PL, Wellman GC. Oxyhemoglobin-induced suppression of voltage-dependent K+ channels in cerebral arteries by enhanced tyrosine kinase activity. Circ Res. 2006;99:1252–1260. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250821.32324.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewell RP, Saundry CM, Bonev AD, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Inhibition of Ca++ sparks by oxyhemoglobin in rabbit cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:295–302. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koide M, Penar PL, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor mediates oxyhemoglobin-induced suppression of voltage-dependent potassium channels in rabbit cerebral artery myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1750–H1759. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00443.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishizawa S, Laher I. Signaling mechanisms in cerebral vasospasm. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takenaka K, Yamada H, Sakai N, Ando T, Nakashima T, Nishimura Y, Okano Y, Nozawa Y. Cytosolic calcium changes in cultured rat aortic smooth-muscle cells induced by oxyhemoglobin. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:620–624. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.4.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wellman GC. Ion channels and calcium signaling in cerebral arteries following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2006;28:690–702. doi: 10.1179/016164106X151972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wickman G, Lan C, Vollrath B. Functional roles of the rho/rho kinase pathway and protein kinase C in the regulation of cerebrovascular constriction mediated by hemoglobin: relevance to subarachnoid hemorrhage and vasospasm. Circ Res. 2003;92:809–816. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000066663.12256.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiguro M, Wellman TL, Honda A, Russell SR, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Emergence of a R-type Ca2+ channel (CaV 2.3) contributes to cerebral artery constriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circ Res. 2005;96:419–426. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000157670.49936.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishiguro M, Puryear CB, Bisson E, Saundry CM, Nathan DJ, Russell SR, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Enhanced myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from a rabbit model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2217–H2225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00629.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earley S, Waldron BJ, Brayden JE. Critical role for transient receptor potential channel TRPM4 in myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Circ Res. 2004;95:922–929. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147311.54833.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Striessnig J, Grabner M, Mitterdorfer J, Hering S, Sinnegger MJ, Glossmann H. Structural basis of drug binding to L Ca2+ channels. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:108–115. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newcomb R, Szoke B, Palma A, Wang G, Chen X, Hopkins W, Cong R, Miller J, Urge L, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Loo JA, Dooley DJ, Nadasdi L, Tsien RW, Lemos J, Miljanich G. Selective peptide antagonist of the class E calcium channel from the venom of the tarantula Hysterocrates gigas. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15353–15362. doi: 10.1021/bi981255g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellman GC, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Gender differences in coronary artery diameter involve estrogen, nitric oxide, and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. Circ Res. 1996;79:1024–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietrich HH, Dacey RG., Jr Molecular keys to the problems of cerebral vasospasm. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:517–530. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laher I, Zhang JH. Protein kinase C and cerebral vasospasm. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:887–906. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald RL, Weir BK. A review of hemoglobin and the pathogenesis of cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 1991;22:971–982. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vollrath BA, Weir BK, Macdonald RL, Cook DA. Intracellular mechanisms involved in the responses of cerebrovascular smooth-muscle cells to hemoglobin. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:261–268. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lan C, Das D, Wloskowicz A, Vollrath B. Endothelin-1 modulates hemoglobin-mediated signaling in cerebrovascular smooth muscle via RhoA/Rho kinase and protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H165–H173. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00664.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pluta RM. Delayed cerebral vasospasm and nitric oxide: review, new hypothesis, and proposed treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:23–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi K, Miyata N, Renic M, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Hemoglobin, NO, and 20-HETE interactions in mediating cerebral vasoconstriction following SAH. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R84–R89. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00445.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleppisch T, Winter B, Nelson MT. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in cultured arterial segments. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2462–H2468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reading SA, Earley S, Waldron BJ, Welsh DG, Brayden JE. TRPC3 mediates pyrimidine receptor-induced depolarization of cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2055–H2061. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00861.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:248–250. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeidan A, Nordstrom I, Dreja K, Malmqvist U, Hellstrand P. Stretch-dependent modulation of contractility and growth in smooth muscle of rat portal vein. Circ Res. 2000;87:228–234. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Colavitti R, Rovira II, Finkel T. Redox-dependent transcriptional regulation. Circ Res. 2005;97:967–974. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000188210.72062.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peiro C, Matesanz N, Nevado J, Lafuente N, Cercas E, Azcutia V, Vallejo S, Rodriguez-Manas L, Sanchez-Ferrer CF. Glycosylated human oxyhaemoglobin activates nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 in cultured human aortic smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:681–690. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito A, Kamii H, Kato I, Takasawa S, Kondo T, Chan PH, Okamoto H, Yoshimoto T. Transgenic CuZn-superoxide dismutase inhibits NO synthase induction in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:1652–1657. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulver RA, Rose-Curtis P, Roe MW, Wellman GC, Lounsbury KM. Store-operated Ca2+ entry activates the CREB transcription factor in vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2004;94:1351–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127618.34500.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wellman GC, Cartin L, Eckman DM, Stevenson AS, Saundry CM, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Membrane depolarization, elevated Ca2+ entry, and gene expression in cerebral arteries of hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2559–H2567. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevenson AS, Gomez MF, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT. NFAT4 movement in native smooth muscle. A role for differential Ca2+ signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15018–15024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahlin C, Owman C, Chang JY, Delgado T, Salford LG, Svendgaard NA. Changes in contractile response and effect of a calcium antagonist, nimodipine, in isolated intracranial arteries of baboon following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Res Bull. 1990;24:355–361. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90089-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida K, Nakamura S, Umezawa T, Nakano M, Tsubokawa T. Effect of diltiazem and thromboxane A2 synthetase inhibitor (OKY-046) on vessels following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 1990;34:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90006-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshimoto Y, Kim P, Sasaki T, Kirino T, Takakura K. Functional changes in cultured strips of canine cerebral arteries after prolonged exposure to oxyhemoglobin. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:867–874. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.5.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]