Abstract

Earlier cross-cultural research on replicability of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) suggested that personality trait structure is universal, but a recent study using an Italian translation has challenged this position. The present article reexamines the psychometric properties of the Italian NEO-PI-R and discusses the importance of orthogonal Procrustes rotation when the replicability of complex factor structures is tested. The arguments are supported by data from a slightly modified translation of the NEO-PI-R, which was administered to 575 Italian subjects. These data show a close replication of the American normative factor structure when targeted rotation is used. Further, the validity of the Italian NEO-PI-R is supported by external correlates, such as demographic variables (age, sex, education), depression, and affect scales.

Keywords: Procrustes rotation, NEO-PI-R, rotational variants, cross-cultural, validity, PANAS, CES-D

Over the past decade, the Five Factor model (FFM) of personality became one of the dominant paradigms in trait psychology (McCrae, 2001). Using translations of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) researchers have replicated the FFM in samples representing five continents and several different language families. However, in several instances, good replications were achieved only through target factor rotation, and many investigators view this method with skepticism.

In a recent study, Caprara, Barbaranelli, Hahn, & Comrey (2001) investigated the factor structure of the NEO-PI-R in Italian subjects (N = 699). In accordance with the Five-Factor Model (FFM), they extracted five factors. After varimax rotation, they found that only Neuroticism (N), Openness (O), and Conscientiousness (C) factors were well defined. They reported that the facet scales of Extraversion (E) and Agreeableness (A) defined their respective factors rather poorly: the varimax rotation combined the E facets of Warmth (E1), Gregariousness (E2), and Positive Emotions (E6) with the A facets of Trust (A1), Altruism (A3), and Tender-Mindedness (A6), and the E facets of Assertiveness (E3), Activity (E4), and Excitement Seeking (E5) with the A facets of Straightforwardness (A2), Compliance (A4), and Modesty (A5). After orthogonal Procrustes rotation, they found that “the solution agreed perfectly with the American target structure, with congruence coefficients ranging from 0.95 to 0.98” (p. 226). However, Caprara et al. (2001) did not consider the results of the targeted rotation because they “feel that this method can in some cases force a solution that would not be found by more conventional rotational criteria” (p. 223). They concluded that the Italian version of the NEO-PI-R “may not be measuring the same thing in Italy that it does in the United States” (p. 226). Using theoretical arguments and empirical data, this article intends to support the use of orthogonal Procrustes rotation and to demonstrate the equivalence between the American and Italian versions of the NEO-PI-R.

Interpersonal axes rotation

In many studies regarding the cross-cultural replicability of the NEO-PI-R (e.g., Kallasmaa, Allik, Realo, & McCrae, 2000; McCrae, Costa, del Pilar, Rolland, & Parker, 1998; McCrae, Zonderman, Costa, Bond, & Paunonen, 1996; Piedmont & Chae, 1997; Rolland, Parker, & Stumpf, 1998) exploratory factor analyses (using varimax rotations) have rearranged the E and A facets into factors better interpreted as Love and Dominance. Love vs. Hate (affiliation) and Dominance vs. Submission (status) are known as the axes of the interpersonal circumplex (Wiggins, 1979) which occupy the same two-dimensional plane defined by E and A (McCrae & Costa, 1989). Within the interpersonal circumplex, Love and Dominance factors are rotational variants of E and A. Theoretical more than empirical arguments are usually used in the choice of the reference axes. Traditionally, personality inventories assess E and A because they are considered more appropriate in the description of individual dimensions, whereas Love and Submission appear more suitable in the explanation of the interpersonal interactions (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1984; McCrae & Costa, 1989). The facets of the NEO-PI-R are designed and computed to assess the E and A factors. However, the E and A facets form a semicircular array, and simple rotations of the axes can produce the alternative interpersonal factors (e.g., Kallasmaa et al., 2000).

Although this rotational difference may be simply arbitrary, it is possible that psychologically meaningful differences may exist between cultures in which Love-Submission or E-A are the most salient dimensions extracted by varimax rotation. It has been proposed that in collectivistic cultures, in which interpersonal relationships are emphasized, Love and Submission are more salient than they are in individualistic cultures (McCrae et al., 1998). However, currently only mixed support has been found for this hypothesis (Kallasmaa et al., 2000).

There are well-known cultural differences between northern and southern Italy (Alcaro, 1999; Peabody, 1985; Petraccone, 2000; see also Galati & Sciaky, 1995). The northern Italians are characterized by a middle-European culture, less traditional and with a high level of individualism. In contrast, in the south, there is a Mediterranean culture, which is low in individualism and high in collectivism, especially “familism.” To test whether the individualism-collectivism dimension is associated with the orientation of the interpersonal axes, NEO-PI-R data from northern and southern samples will be factor analyzed. In agreement with the individualism-collectivism hypothesis, the northern sample should yield the normative E and A factors, while the southern sample should yield the alternative Love and Submission factors.

Orthogonal Procrustes rotation

Analytical rotation procedures such as varimax are exploratory in nature and can result in dimensions that have theoretically arbitrary locations in the factor space. This is particularly true with variables that do not show a simple structure but rather a circumplex order, as do the facets of E and A (McCrae & Costa, 1989). Small differences in the observed facets’ loadings can yield large differences in the position of the axes and dramatically different solutions. Therefore, varimax rotation does not seem to be the optimal method to test invariance between factor structures. McCrae et al. (1996) suggested an alternative method, orthogonal Procrustes rotation (Schönemann, 1966), which rotates factors to minimize the sums of squares of deviations from the target matrix. The technique performs a theoretically guided rotation that aligns the position of the axes in the factor space, under the constraint of maintaining orthogonality and without affecting the relative positions of the facets’ loadings. The extent of the fit achieved between the two orthogonal matrixes can be assessed by congruence coefficients (Harman, 1976, p. 344). A congruence coefficient of .90 or higher has been traditionally considered evidence of factor replication (Barrett, 1986; Mulaik, 1972).

Orthogonal Procrustes rotation, like structural equation modeling, attempts to achieve the maximum fit possible between a target structure and the empirical data. However, this rotational method does not impose or distort the empirical data to obtain the target structure. In fact, there are several examples of failed attempts to replicate factor structures using the orthogonal Procrustes rotation. For instance, using Procrustes rotation, Ball, Tennen, and Kranzler (1999) did not replicate the original factor structure of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI; Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, 1993); Helmes and Nielson (1998) did not replicate the originally postulated subscale structure of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977); Gosling and John (1998) did not fully replicate the FFM in nonhuman animals.

As an illustrative example, the data of Caprara et al. (2001) were rotated with the Procrustes procedure to the best fit with the hypothetical 5-factor matrix presented in the first 5 columns of Table 1.

Table 1.

An arbitrary target matrix for Procrustes rotation.

| NEO-PI-R scale | N | E | O/C | A | C/O | Facet Congruence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1: Anxiety | .81 | .02 | −.01 | −.01 | −.10 | .95 |

| N2: Angry Hostility | .63 | −.03 | .01 | −.48 | −.08 | .96 |

| N3: Depression | .80 | −.10 | .02 | −.03 | −.26 | .97 |

| N4: Self-Consciousness | .73 | −.18 | −.09 | .04 | −.16 | .98 |

| N5: Impulsiveness | .49 | .35 | .02 | −.21 | −.32 | .95 |

| N6: Vulnerability | .70 | −.15 | −.09 | .04 | −.38 | 1.00 |

| E1: Warmth | −.12 | .66 | .18 | .38 | .13 | .98 |

| E2: Gregariousness | −.18 | .66 | .04 | .07 | −.03 | .96 |

| E3: Assertiveness | −.32 | .44 | .23 | −.32 | .32 | .98 |

| E4: Activity | .04 | .54 | .16 | −.27 | .42 | .99 |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | .00 | .58 | .11 | −.38 | −.06 | .93 |

| E6: Positive Emotions | −.04 | .74 | .19 | .10 | .10 | .92 |

| O1: Fantasy | .18 | .18 | .58 | −.14 | −.31 | .98 |

| O2: Aesthetics | .14 | .04 | .73 | .17 | .14 | .97 |

| O3: Feelings | .37 | .41 | .50 | −.01 | .12 | .98 |

| O4: Actions | −.09 | .23 | .15 | −.13 | .74 | −.13 |

| O5: Ideas | −.33 | .17 | −.08 | .06 | .75 | .00 |

| O6: Values | −.23 | −.28 | −.04 | .22 | .57 | −.30 |

| A1: Trust | −.35 | .22 | .15 | .56 | .03 | .94 |

| A2: Straightforwardness | −.03 | −.15 | −.11 | .68 | .24 | .95 |

| A3: Altruism | −.06 | .52 | −.05 | .55 | .27 | 1.00 |

| A4: Compliance | −.16 | −.08 | −.00 | .77 | .01 | .95 |

| A5: Modesty | .19 | −.12 | −.18 | .59 | −.08 | .98 |

| A6: Tender-Mindedness | .04 | .27 | .13 | .62 | .00 | .93 |

| C1: Competence | −.41 | .17 | .13 | .03 | .64 | .96 |

| C2: Order | −.04 | .06 | −.19 | .01 | .70 | .92 |

| C3: Dutifulness | −.20 | −.04 | .01 | .29 | .68 | .96 |

| C4: Achievement Striving | −.19 | .22 | .57 | .04 | −.04 | .14 |

| C5: Self-Discipline | −.15 | −.01 | .75 | −.09 | .16 | .28 |

| C6: Deliberation | −.13 | .08 | .49 | −.07 | −.15 | −.23 |

| Factor Congruence | .95 | .91 | .54 | .94 | .49 | .77 |

Note: This matrix was created by exchanging the loadings of the last three facets of O with the last three facets of C in the American normative data (Costa & McCrae, 1992, Table 5).

This matrix presents two rearranged factors created by exchanging, in the American normative data (Table 5; Costa & McCrae, 1992), the loadings of the last three facets of O with the last three facets of C, and vice versa. This substitution is similar to the empirical rearrangement of the E and A facets, except that the facets of O and C do not naturally form a circumplex. After orthogonal Procrustes rotation, the congruence coefficients were good for N, E, and A, but not for O/C, and C/O (Table 1). Congruence coefficients for the rearranged facets were also very low, as shown in the last column of Table 1. The result of this example indicates that orthogonal Procrustes rotation does not force the data to fit the hypothetical matrix. Most notably, with a Monte Carlo simulation, McCrae et al. (1996) have shown that the orthogonal Procrustes rotation is relatively immune to capitalization on chance. They generated one thousand random matrices and each matrix was rotated to optimally fit the American normative target. McCrae et al. (1996) then examined the distribution of congruence coefficients of these random data and found that the mean values ranged from .32 to .34 for the five factors. “These low mean values clearly demonstrate that orthogonal Procrustes rotation cannot force random data into a spuriously close fit with a target. In fact, not 1 of the 5,000 factor congruence coefficients in the simulation reached .80, still less the .90 level that is traditionally considered evidence of factor replication” (McCrae et al., 1996, p.560). Thus, in spite of the name--Procrustes, in the Greek mythology, compelled his victims to fit his iron bed, cutting off the legs of those who were too tall and stretching the bodies of those who were too short --orthogonal Procrustes rotation does not force data to fit every hypothesis.

Although orthogonal Procrustes rotation appears to be an optimal strategy to test the replicability of factor structure, unfortunately, it is not yet a widely used rotational procedure. Furthermore, the replicability of the factor structure is only one aspect of a test’s validity. In order to conclude that the Italian and American versions measure the same dimensions, it is necessary to investigate other aspects of the validity, such as their relation with external measures.

External Validity

Some data on the validity of the Italian NEO-PI-R are already present in the literature, based upon the relations between the five factors and demographic variables. Cross-cultural research, including both American and Italian subjects, has shown universal patterns in maturational changes (McCrae et al., 1999) and sex differences (Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae, 2001).

Other published evidence of concurrent validity for the Italian NEO-PI-R comes from the study of Caprara et al. (2001). They factor analyzed the data from the NEO-PI-R and the Comrey Personality Scales (CPS; Caprara, Barbaranelli, & Comrey, 1992; Comrey, 1995). They found that in Italian subjects N is similar to the CPS Emotional Stability vs. Neuroticism; E is similar to the CPS Extraversion vs. Introversion; O is similar to the CPS Social Conformity vs. Rebelliousness; A is similar to two CPS factors, Trust vs. Defensiveness and Empathy vs. Egocentrism; and C is similar to the CPS Orderliness vs. Lack of Compulsion. Thus, a good correspondence was found between the NEO-PI-R and the Comrey scales that define similar domains. Further, to provide additional evidence of external validity, this article examines the correlation between the Italian NEO-PI-R with self-report measures of Positive and Negative Affect (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988; Terracciano, McCrae, & Costa, in press), and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977).

Present Study

In brief, the conclusion of Caprara et al. (2001) is limited by an incomplete analysis, since they relied upon exploratory factor analysis (varimax rotated factor solution) and did not consider targeted rotation that more directly tests factor invariance. This article intends to provide additional data in support of the Italian NEO-PI-R’s validity. The present study uses a slightly modified Italian version and data recruited from a new sample of 575 Italian subjects. The intent is to examine the factor structure of this revised version, its psychometric proprieties, and its correlations with external criteria.

Method

Participants

A sample of 575 subjects was recruited in north (n = 208) and south (n = 367) Italy, from student and non-student populations. Two student samples were recruited from the University of Trieste and the University of Naples. Two non-student samples, from north and south Italy, were recruited using a snow-ball strategy. Initial subjects asked other persons (relatives, friends, partners and acquaintances) to take part in a psychological study by completing questionnaires and recruiting further participants. Volunteers signed a consent form (approved by the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board), provided background information, and then completed questionnaires at home. Volunteers reported their address if interested in feedback concerning the personality profile. The total sample (N = 575) includes 359 women, 214 men and two subjects whose sex is unknown. The age range was 18 to 87 (age: M = 27.9, SD = 9.81). Volunteers reported their level of education as being average to high in all four samples.

Measures

NEO-PI-R

The NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is a 240-item questionnaire specifically designed to measure the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality. Eight-item scales are used to measure six specific traits or facets for each of the five factors. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and scales are balanced to control for the effects of acquiescence. The present study used the Italian version of the NEO-PI-R translated by Caprara and Barbaranelli (Caprara et al., 2001; McCrae et al., 1999), with the addition of 23 alternative translations of items that showed poor psychometric properties in a previous study (McCrae et al., 1999). For the analysis conducted in the present study, 8 of the Caprara and Barbaranelli items were replaced with the new alternative items that improved the internal consistency of the facet scales. These substitutions aim to improve the already excellent translation of Caprara and Barbanelli (Caprara et al., 2001).

Other measures

Participants completed the Italian version of the PANAS scales (Terracciano, et al., in press) which are composed of 10 items each. With respect to each item, subjects reported, on a 5-point Likert scale, how they feel in general (that is intended to assess trait affect). The Positive Affect scale reflects the level of pleasant engagement, the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, excited, active, and determined. The Negative Affect scale reflects a general dimension of unpleasant engagement and subjective distress that subsumes a broad range of aversive affects including fear, nervousness, guilt, and shame.

About three months later, a subset of participants (n = 60) completed the affect scales for a second time. In addition, the same subset completed the CES-D (Fava, 1983; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item self-rating scale, sensitive in detecting depressive symptoms in the general population. The 20 items were selected to represent the major symptoms of depression (e.g., poor appetite, difficulty in concentrating) with emphasis on the affective components (depressed mood). Respondents reported the frequency of symptom occurrence on a four-point scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most of the time or 5 to 7 days) within the last week. Four items are reverse-keyed.

Results and Discussion

Reliability

The first Column in Table 2 gives the internal consistency for all facet scales of the revised Italian version of the NEO-PI-R. For the five domain scales, the Cronbach alphas were 0.91, 0.88, 0.87, 0.86, and 0.91 for N, E, O, A, and C, respectively. These values were as high as the corresponding values for the original scales (Costa & McCrae, 1992, Table 5). Of the 30 facet scales, the internal consistency reliabilities range from 0.46 to 0.84 with a median of 0.73. These values are comparable to the American data.

Table 2.

Cronbach alphas, factor loadings, and congruence coefficients for the Italian NEO-PI-R scales after varimax and Procrustes rotation.

| Varimax-rotated component

|

Procrustes-rotated component

|

Facet Congruence | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEO-PI-R scale | α | I | II | III | IV | V | N | E | O | A | C | |

| N1: Anxiety | 0.77 | 82 | −04 | 04 | 04 | −04 | 82 | −06 | −03 | 05 | −02 | 99 |

| N2: Angry Hostility | 0.73 | 63 | −30 | −13 | −40 | −02 | 64 | −13 | −15 | −47 | 02 | 97 |

| N3: Depression | 0.84 | 78 | −18 | 05 | 13 | −32 | 79 | −22 | −01 | 07 | −30 | 98 |

| N4: Self-Consciousness | 0.73 | 63 | −29 | −04 | 24 | −27 | 63 | −36 | −09 | 12 | −26 | 95 |

| N5: Impulsiveness | 0.64 | 37 | 23 | 25 | −41 | −38 | 42 | 39 | 21 | −27 | −35 | 96 |

| N6: Vulnerability | 0.74 | 71 | −05 | −02 | 10 | −47 | 72 | −08 | −09 | 08 | −45 | 99 |

| E1: Warmth | 0.78 | −20 | 81 | 19 | 09 | 06 | −20 | 72 | 15 | 41 | 05 | 99 |

| E2: Gregariousness | 0.77 | −07 | 74 | 00 | −05 | −08 | −07 | 70 | −04 | 24 | −07 | 95 |

| E3: Assertiveness | 0.70 | −44 | 30 | 14 | −50 | 24 | −42 | 48 | 18 | −34 | 25 | 98 |

| E4: Activity | 0.55 | −01 | 41 | −02 | −45 | 38 | −01 | 54 | −02 | −24 | 40 | 97 |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | 0.61 | −10 | 28 | 23 | −54 | −21 | −06 | 49 | 23 | −38 | −19 | 95 |

| E6: Positive Emotions | 0.77 | −26 | 62 | 29 | −20 | −02 | −23 | 66 | 28 | 07 | −02 | 94 |

| O1: Fantasy | 0.81 | 16 | 17 | 68 | −04 | −23 | 22 | 20 | 65 | 07 | −23 | 95 |

| O2: Aesthetics | 0.73 | 19 | 24 | 69 | 07 | 12 | 24 | 22 | 66 | 21 | 11 | 96 |

| O3: Feelings | 0.64 | 19 | 36 | 63 | −26 | 10 | 24 | 45 | 60 | −05 | 11 | 98 |

| O4: Actions | 0.55 | −16 | 15 | 51 | −16 | −11 | −11 | 23 | 51 | −07 | −12 | 97 |

| O5: Ideas | 0.77 | −14 | 00 | 74 | −03 | 18 | −08 | 04 | 75 | 02 | 16 | 99 |

| O6: Values | 0.52 | −19 | −12 | 57 | 02 | −27 | −13 | −09 | 58 | −01 | −29 | 94 |

| A1: Trust | 0.80 | −26 | 53 | 16 | 38 | −01 | −27 | 35 | 13 | 56 | −03 | 97 |

| A2: Straightforwardness | 0.77 | 04 | 21 | 04 | 69 | 21 | 01 | −08 | 00 | 73 | 18 | 98 |

| A3: Altruism | 0.69 | −07 | 63 | 15 | 33 | 34 | −09 | 45 | 11 | 57 | 33 | 97 |

| A4: Compliance | 0.66 | −12 | 15 | −10 | 72 | −11 | −15 | −15 | −13 | 70 | −14 | 96 |

| A5: Modesty | 0.71 | 26 | 03 | −08 | 60 | −05 | 23 | −21 | −12 | 56 | −07 | 98 |

| A6: Tender-Mindedness | 0.46 | 13 | 40 | 29 | 37 | 07 | 13 | 23 | 24 | 52 | 06 | 96 |

| C1: Competence | 0.59 | −31 | 09 | 07 | −02 | 71 | −33 | 08 | 10 | 03 | 70 | 98 |

| C2: Order | 0.74 | 04 | −10 | −19 | −03 | 67 | 01 | −10 | −17 | −05 | 67 | 97 |

| C3: Dutifulness | 0.72 | −10 | 09 | −01 | 25 | 78 | −14 | −03 | 00 | 29 | 77 | 99 |

| C4: Achievement Striving | 0.71 | −12 | 14 | 09 | −25 | 74 | −13 | 22 | 11 | −15 | 75 | 99 |

| C5: Self-Discipline | 0.80 | −24 | 05 | −04 | 02 | 81 | −27 | 02 | −01 | 06 | 80 | 98 |

| C6: Deliberation | 0.78 | −28 | −21 | −16 | 35 | 54 | −32 | −35 | −13 | 24 | 52 | 98 |

| Factor Congruence | 97 | 88 | 95 | 89 | 98 | 98 | 96 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 97 | |

Note: N = 575. Procrustes rotation is targeted to the American normative structure. Decimal points are omitted; loadings with absolute values greater than or equal to.40 are given in bold. All congruence coefficients are higher than that of 99% of rotations from random data.

Factor analysis

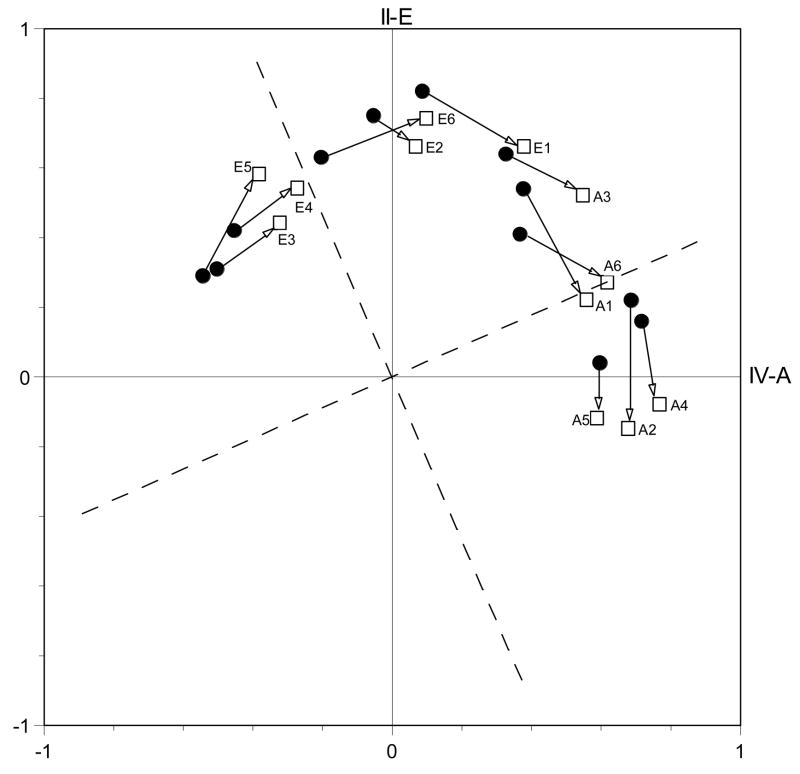

The 30 facet scales were factored using principal component analysis. Table 2 shows the varimax-rotated five-factor solution. Similar to Caprara et al. (2001) for O and C factors (the third and fifth factors), the facet scores had loadings of at least 0.40 on their expected factors with no major loadings elsewhere. Five facets of N loaded on the first factor, and only N5: Impulsiveness had its highest loading elsewhere. As in several previous studies, the E and A factors were not easily identified. The second and fourth varimax factors produced the alternative interpersonal factors of Love and Submission. E1: Warmth, E2: Gregariousness, E6: Positive Emotions, A1: Trust, A3: Altruism, and A6: Tender-Mindedness define the former. A2: Straightforwardness, A4: Compliance, A5: Modesty, low E3: Assertiveness, low E4: Activity, and low E5: Excitement Seeking define the latter factor. These alternative factors derive from rotational differences within the two-dimensional plane of the interpersonal circumplex.* Figure 1 shows that the major difference between the Italian varimax factor structure (Table 2) and the normative American structure appears to be the position of the axes. The arrangement of the facets in the plane is very similar except that the Italian axes are rotated about 23 degrees away from the American axes.§

Figure 1.

Factor plot of NEO-PI-R Extraversion (E1 to E6) and Agreeableness (A1 to A6) facets in Italian and American normative data. See Table 1 for facet scale labels. The figure was created by plotting E and A facets using Italian varimax-rotated factor loadings (filled circle) and American factor loadings (empty square), with arrows pointing in the direction of the corresponding American facets. The dashed lines represent the position of Extraversion and Agreeableness axes in the Italian data.

In this new Italian sample, the interpersonal axes were closer to the normative E and A, compared with the Caprara et al. (2001) varimax solution. In fact, in that sample the axes were rotated about 33 degrees away from the American axes. Difference in the interpersonal axes position were also observed between the northern and southern Italian samples, but not associated in the expected direction with the individualism-collectivism dimensions. Contrary to the hypothesis, in the southern Italy sample the facets of E and A describe essentially the expected factors, whereas in the northern sample, the facets define the Love and Submission factor variants. In fact, the congruence coefficients for E and A factors between the varimax-rotated factors and the American normative matrix were good for the southern sample, .93 and .96 respectively, but were only .86 and .87 for the northern sample. Also the congruence coefficients for E and A facets were larger in the southern (range from .86 to .99, M = .95, SD = .04) than the northern sample (range from .67 to .94, M = .86, SD = .08; the full Varimax and Procrustes solutions, and congruence coefficients for the southern and northern sample are available upon request from the author). The degrees of rotation of the interpersonal axes from the American normative structure were 10 for the southern and 26 for the northern sample. It is noteworthy to consider that varimax rotation indicated E and A as the most salient factors in the southern sample. Thus the same Italian version can achieve the normative varimax structure as well as the alternative rotational variant, Love and Dominance/Submission. The differences between the Italian samples are in line with the discrepancies found in two Korean samples (Kallasmaa et al., 2000), and the fact that in a Filipino sample, analysis of data from a university student subsample yielded standard E and A factors while Love and Submission emerged in a business school subsample (McCrae et al., 1998). These differences within culture indicate the need to explore additional causes of the interpersonal axes position (e.g., proportion of males and females, age, scores on the dimensions of the FFM), other than the cultural collectivism-individualism dimension.

Orthogonal Procrustes Rotation

These rotational differences within the two-dimensional plane of the interpersonal circumplex do not indicate a failure in the cross-cultural replicability of the NEO-PI-R factor structure. In fact, the realignment of the axes in the factor space, using a confirmatory Procrustes procedure, produces the factor solution presented in Table 2. After orthogonal Procrustes rotation all five factors are well defined, with all 30 facet scores loading chiefly on the intended factors. Congruence coefficients comparing the Italian factors with American normative factors ranged from 0.96 to 0.98. Variable congruence coefficients for the 30 facet scales were greater or equal to 0.94--higher than that of 99% of rotations from random data (McCrae et al., 1996). Thus, the Italian version of the NEO-PI-R closely replicates the American normative structure.

External Validity

At least by internal criteria, the Italian version of the NEO-PI-R shows convergent and discriminant validity. However, analysis relying merely upon rotational method may not resolve the question of whether the Italian NEO-PI-R measures dimensions similar to the American NEO-PI-R. External criteria are thus important to confirm the validity of the Italian version, and replication of American findings can corroborates the equivalence between the two versions.

Demographic variables

Studies on American samples as well as cross-cultural research across a large number of cultures and languages have shown a significant pattern of associations between demographic variables and NEO-PI-R scales (Costa et al., 2001; McCrae et al., 1999). The present study, using the revised version of the Italian NEO-PI-R, replicates those findings. In fact, the correlations of age with the five factors suggests a developmental pattern similar to the American data (Costa & McCrae, 1994; McCrae & Costa, 1990), with systematic declines in the mean levels of N, E, and O, and increases in A and C. In particular, age correlates −0.19 (p < .01) with N, −0.20 (p < .01) with E, −0.25 (p< .01) with O, 0.08 (p < .05) with A, and 0.20 (p < .01) with C.

Also in line with the American findings and some theoretical predictions are the sex differences (Costa et al., 2001). These differences were analyzed by using paired t-tests. Women were found significantly higher than men with respect to the N, A and O factors (p < .001). No significant differences were found for the E and C factors. At the facet level, women were found to score significantly higher than men in all facets of N (p < .05), and four of the six facets of A (p < .05). Sex differences on A1: Trust and A4: Compliance did not reach statistical significance. Sex differences in the facets of E are predictable from the interpersonal circumplex viewpoint: Women reported themselves to be higher than men in E1: Warmth (p < .05), E2: Gregariousness (p < .001), and Positive E6: Emotions (p < .05) but lower in E3: Assertiveness (p < .001), and E5: Excitement-seeking (p < .01). As in American data, Italian men were slightly higher than women in C1: Competence (p < .05), and C6: Deliberation (p < .05), but there were no other consistent differences in facets of C. Women were found to score higher also on all facets of the O domain, with the first four facets reaching statistical significance (p < .01). The fact that women are slightly higher than men in O5: Ideas is the only interesting exception to the successful replication of the American sex differences.

Level of education is another demographic variable that showed meaningful associations with personality traits. As in the American data (Costa & McCrae, 1992, p. 55), in the present study O showed the strongest association with level of education (r = 0.15; p < .01). The above pattern of correlations provides a reasonably clear picture and is very consistent with expectations and previous research. Further evidence of external validity derives from the relation of the five factors with affect scales.

PANAS

A large body of literature supports the assumption of temperamental differences in experience of positive or negative affect: “extroverts are simply more cheerful and high-spirited than introverts; individuals high in N are more prone to negative affect than those low in N” (McCrae & Costa, 1991, p. 228). Furthermore, McCrae and Costa (1991) proposed that A and C play an instrumental influence on mood and emotions. “Agreeable people are warm, generous and loving. Conscientious people are competent, efficient and hard working” (McCrae & Costa, 1991, p. 228). These characteristics create conditions, life circumstances, and lifestyle differences that promote differential levels of positive and negative affect. As can be seen in Table 3, the correlations among the five factors and the PANAS scale are consistent with the above hypothesis and with previous research on American samples (Costa & McCrae, 1980; McCrae & Costa, 1991; Watson & Clark, 1992). In fact, E and in particular E4: Activity (r = .45; p < 01) and E6: Positive Emotions (r = .47; p < 01), were related to Positive Affect. As expected, N and its facets were found strongly related to Negative Affect. In line with the hypotheses, significant but moderate correlations were found between C and both affect scales, and between A and Negative Affect. Finally, O showed only a modest correlation with Positive Affect.

Table 3.

Correlations of NEO-PI-R domains with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D).

| NEO-PI-R | Positive Affecta | Negative Affecta | CES-Db |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | −.34* | .69* | .70* |

| Extraversion | .51* | −.29* | −.47* |

| Openness | .34* | .01 | −.11 |

| Agreeableness | .00 | −.20* | −.22 |

| Conscientiousness | .38* | −.27* | −.42* |

Note:

N = 575,

n = 60.

p < .01, two-tailed.

CES-D

Further, the NEO-PI-R scales appear to be good predictors of the CES-D score. In fact, as reported in Table 3, and consistent with expectations based in theory and previous research (Costa & McCrae, 1996), the CES-D scale shows a strong positive correlation with N and a significant negative correlation with the E factor. At the facet level, N3: Depression shows the strongest relation with the CES-D (r = .68; p < .01). The other N facets were significantly correlated (p < .01). E3:Assertiveness, E4: Activity, and E6: Positive Emotions were the facets of E with significant negative correlations (p < .01). At present, there are no published data regarding the correlation between the CES-D and the other three factors. However, Bagby, Joffe, Parker, Kalemba, & Harkness, (1995) reported that depressed subjects scored low on C and had average levels on O and A, besides the very high score in N and low score on E. Table 3 presents comparable results. These correlations reveal a clear pattern. High levels of Neuroticism, in particular N3: Depression, low Extraversion, and low Conscientiousness appear to be the personality profile of subjects at risk for depression.

Conclusion

A major aim of this study was to reexamine conceptual arguments and to provide empirical data in support of the targeted rotation in factor analysis. This study also tested the cross-cultural replicability of the NEO-PI-R factor structure in an Italian sample. A confirmatory analysis using orthogonal Procrustes rotation showed that the Italian version replicates the American normative factor structure. In fact, congruence coefficients for the five factors range from 0.96 to 0.98, and all facets clearly define the intended factor. In addition, the validity of the Italian NEO-PI-R was clearly supported by external correlates. Personality questionnaires that have been shown to be valid across culture, such as the NEO-PI-R or the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975) to name a few, provide a common metric by which cultures can be compared. Using these instruments and data recruited from samples around the world it is possible to investigate the effects of the biological (genetic) and environmental (cultural) underpinnings of personality traits.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Paul T. Costa, Jr., and Robert R. McCrae for helpful comments and suggestion concerning data analysis and manuscript preparation. I wish to thank Ivan Conte, Lisa Di Blas, Carmen Migliaccio, and Bruno Varriale for their help in recruiting subjects, and Giovanni Fava for providing the Italian version of the CES-D.

Footnotes

De Raad, Di Blas, and Perugini (1998) found that an Extraversion and an Agreeableness factor emerged from the analyses of two independent constructed Italian trait taxonomies (Caprara and Perugini, 1994; Di Blas and Forzi, 1998). Of interest, the Italian NEO PI-R varimax solution does not seem to deviate in the direction of these “emic” Italian structures, but follows a pattern observed in other cultures.

“The degrees of rotation were estimated from the inverse cosines of appropriate entries in the factor transformation matrix from the Procrustes analysis in which the varimax structure was rotated to best approximate the American structure” (Kallasmaa et al., 2000, p. 273).

References

- Alcaro M. Southern identity: Form of mediterranean culture. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri; 1999. Sull’identita’ meridionale: Forme di una cultura mediterranea. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Joffe RT, Parker JDA, Kalemba V, Harkness KL. Major depression and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1995;9:224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Factor replicability and validity of the Temperament and Character Inventory in substance-dependent patients. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:514–524. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P. Factor comparison--an examination of 3 methods. Personality and Individual Differences. 1986;7:327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Comrey AL. Validation of the Comrey Personality Scales on an Italian sample. Journal of Research in Personality. 1992;26:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Hahn R, Comrey AL. Factor analyses of the NEO-PI-R inventory and the Comrey Personality Scales in Italy and the United States. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Perugini M. Personality described by adjectives: the generalizability of the Big Five to the Italian lexical context. European Journal of Personality. 1994;8:357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL. Revised manual and handbook of interpretations for the Comrey Personality Scales. San Diego: EdITS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Influence of Extraversion and Neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality from adolescence through adulthood. In: Halverson CF, Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Mood and personality in adulthood. In: Magai C, McFadden SH, editors. Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 369–383. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, Terracciano A, McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:322–331. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Raad B, Di Blas L, Perugini M. Two independently constructed Italian trait taxonomies: Comparisons among Italian and between Italian and Germanic languages. European Journal of Personality. 1998;12:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Di Blas L, Forzi M. An alternative taxonomic study of personality-descriptive adjectives in the Italian language. European Journal of Personality. 1998;12:75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck M. Personality and individual differences. London: Plenum Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, CA: EdITS; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA. Assessing depressive symptoms across cultures: Italian validation of the CES-D self-rating scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983;39:249–251. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198303)39:2<249::aid-jclp2270390218>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati D, Sciaky R. The representation of antecedents of emotions in northern and southern Italy: A textual analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1995;26:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, John OP. Personality dimensions in dogs, cats, and hyenas; 1998, June; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Society; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Harman HH. Modern factor analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Helmes E, Nielson WR. An examination of the internal structure of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale in two medical samples. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25:735–743. [Google Scholar]

- Kallasmaa T, Allik J, Realo A, McCrae RR. The Estonian version of the NEO-PI-R: An examination of universal and culture-specific aspects of the five-factor model. European Journal of Personality. 2000;14:265–278. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR. 5 years of progress: A reply to Block. Journal of Research in Personality. 2001;35:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins’s circumplex and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:586–595. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . Personality in adulthood. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Adding liebe und arbeit: The full Five-Factor Model and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Jr, Lima MP, Simões A, Ostendorf F, Angleitner A, Maru©i I, Bratko D, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Chae JH, Piedmont RL. Age differences in personality across the adult lifespan: Parallels in five cultures. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:466–477. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Jr, del Pilar GH, Rolland JP, Parker WD. Cross-cultural assessment of the five-factor model: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1998;29:171–188. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Jang KL, Livesley WJ, Riemann R, Angleitner A. Sources of structure: Genetic, environmental, and artifactual influences on the covariation of personality traits. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:511–535. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Zonderman AB, Costa PT, Jr, Bond MH, Paunonen SV. Evaluating replicability of factors in the revised NEO personality inventory: Confirmatory factor analysis versus Procrustes rotation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Mulaik SA. The foundations of factor analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Peabody D. National Characteristics. Cambridge: Cambridge University press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Petraccone C. The two cultures: Northern and Southern in the history of Italy. Bari: Laterza; 2000. Le due civilta’: Settentrionali e meridionali nella storia d’Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Chae JH. Cross-cultural generalizability of the Five-Factor Model of personality: Development and validation of the NEO PI-R for Koreans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1997;28:131–155. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland JP, Parker WD, Stumpf H. A psychometric examination of the French translations of the NEO-PI-R and NEO-FFI. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1998;71:269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Schönemann PH. A generalized solution of the orthogonal Procrustes problem. Psychometika. 1966;31:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Factorial and construct validity of the Italian Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) European Journal of Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.19.2.131. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. On traits and temperament: General and specific factors of emotional experience and their relation to the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:441–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:395–412. [Google Scholar]