Abstract

The obligate intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii, a member of the phylum Apicomplexa that includes Plasmodium spp., is one of the most widespread parasites and the causative agent of toxoplasmosis. Adhesive complexes composed of microneme proteins (MICs) are secreted onto the parasite surface from intracellular stores and fulfil crucial roles in host-cell recognition, attachment and penetration. Here, we report the high-resolution solution structure of a complex between two crucial MICs, TgMIC6 and TgMIC1. Furthermore, we identify two analogous interaction sites within separate epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) domains of TgMIC6—EGF2 and EGF3—and confirm that both interactions are functional for the recognition of host cell receptor in the parasite, using immunofluorescence and invasion assays. The nature of this new mode of recognition of the EGF domain and its abundance in apicomplexan surface proteins suggest a more generalized means of constructing functional assemblies by using EGF domains with highly specific receptor-binding properties.

Keywords: apicomplexa, microneme proteins, invasion, solution structure, EGF

Introduction

The intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is uniquely adapted to infect a wide range of hosts, including virtually all warm-blooded animals and humans. Toxoplasmosis causes a variety of disease states in humans, including severe disseminated disease in immunosuppressed individuals owing to reactivation of encysted parasites and birth defects in infants where mothers are exposed to the parasite for the first time during pregnancy (Hill & Dubey, 2002). T. gondii also causes significant disease and economic loss in the farming industry, principally by inducing abortion and fetal abnormality in sheep (Fusco et al, 2007). Raw and undercooked meat from infected animals represents a principal source of human infection with T. gondii (Dubey, 2004). Around 500 million of the world's population have been infected with Toxoplasma, and toxoplasmosis is considered to be the third leading cause of death attributed to foodborne illness in the United States.

Toxoplasma and other apicomplexan parasites, including Plasmodium (the agents of malaria), share a set of apical secretory organelles such as micronemes and rhoptries, which release a large number of soluble and membrane proteins onto the parasite's surface during invasion. Microneme proteins (MICs) are stored in the micronemes before secretion, after which they participate in the attachment of parasites to the host cell surface (Carruthers et al, 1999) and in the formation of a connection with the parasite actinomyosin system (Jewett & Sibley, 2003), which drives motility and invasion (Soldati & Meissner, 2004). The integrity of the MIC cargo is controlled by several molecular checkpoints during transport and after secretion, which include conformation-dependent sorting and proteolytic processing events. These processes are particularly well characterized for the TgMIC4–MIC1–MIC6 complex (TgMIC4–1–6) from T. gondii (Reiss et al, 2001; Saouros et al, 2005a).

The TgMIC4–1–6 complex binds tightly to host cell receptors and has a central function in invasion and virulence (Blumenschein et al, 2007). TgMIC6 contains a membrane-spanning domain and a carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail encompassing the sorting signal that is essential for the accurate targeting of the complex to the micronemes (Fig 1A). TgMIC6 also contains three extracellular epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) domains, the first of which is proteolytically removed during its transport to the microneme organelles and is not present in mature forms of the complex (Meissner et al, 2002a). In addition, an interaction between the third EGF-like domain of TgMIC6 (TgMIC6-EGF3) and the C-terminal galectin-like domain of TgMIC1 (TgMIC1-GLD; Fig 1A) is crucial for the correct folding of TgMIC6-EGF3 and the transport of the whole complex to the micronemes (Reiss et al, 2001; Saouros et al, 2005a). TgMIC1 comprises a tandem repeat of a new cell-binding motif called the microneme adhesive repeat (MAR), which has been shown to bind to sialylated oligosaccharides on the host cell surface and recruitment of the third component of the complex, TgMIC4 (Blumenschein et al, 2007). TgMIC4 is also a soluble cell-adhesion protein composed of six apple domains that interacts with TgMIC1 and is processed extracellularly, releasing a 15-kDa C-terminal fragment (Brecht et al, 2001).

Figure 1.

TgMIC6-EGF2 interacts independently with TgMIC1-GLD. (A) Schematic representation of the domain structure of TgMIC6 (top) and TgMIC1 (bottom). Microneme adhesive repeat (MAR) domain, galectin-like domain (GLD), epidermal growth factor-like (EGF), transmembrane (TM) and acidic domains are shown. The first EGF domain is proteolytically removed during transport to the micronemes. (B) Gel filtration profiles for TgMIC6-EGF2 (green), TgMIC1-GLD (orange) and TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex (blue). (C) Isothermal titrations of TgMIC1-GLD with TgMIC6-EGF2. Analysis of the titration data shows Kd=53±13 nM; ΔH=−1820±19 cal mol−1 and ΔS=27.2 eu. MIC, microneme proteins.

Here, we describe a new interaction between TgMIC1 and the second EGF domain from TgMIC6 (TgMIC6-EGF2), and provide a high-resolution basis for assembly of this complex. Experiments based on immunofluorescence studies and host cell invasion assays indicate that both MIC1–MIC6 interactions contribute to the formation of active host cell-binding sites for the invasion of T. gondii. Our study provides a new insight into the mode of interaction between TgMIC1–4–6 and host receptors, as both EGF domains contribute to MIC1 recruitment, recognition of host cell and subsequent invasion.

Results And Discussion

EGF2 from TgMIC6 interacts independently with TgMIC1

Although interactions between MICs are of central importance to their integrity and surface presentation, little is known about the high-resolution determinant of complex assembly. For example, the mature extracellular portion of TgMIC6 contains two canonical EGF domains (EGF2 and EGF3; Fig 1A), and although TgMIC6-EGF3 is known to interact with the C-terminal galectin-like domain of TgMIC1 (TgMIC1-GLD; supplementary Fig 1 online; Reiss et al, 2001; Saouros et al, 2005a), no role has been reported for the second EGF domain (TgMIC6-EGF2). To address this issue, the second EGF domain from the extracellular portion of mature TgMIC6 (TgMIC6-EGF2) was produced in Escherichia coli and assayed for binding to TgMIC1-GLD by gel filtration (Fig 1B). Examination of the gel filtration profiles showed the co-elution of a protein complex of around 25 kDa molecular weight, corresponding to TgMIC1-GLD with TgMIC6-EGF2. To determine the affinity of this interaction, the binary complex was characterized by using isothermal calorimetry. The binding data for TgMIC1-GLD and TgMIC6-EGF2 followed a standard binding curve. Recorded measurements for enthalpy changes during the titration were fit to a model for a single binding event yielding Kd=53±13 nM with an observed stoichiometry consistent with a 1:1 interaction (Fig 1C).

A new and specific mode of EGF domain recognition

The high-resolution solution structure of the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex was solved by using heteronuclear multidimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Fig 2A,B; supplementary Table I online). In agreement with the structure of TgMIC1-GLD (Saouros et al, 2005a), this region shows the classic β-sandwich of a galectin-like domain when in complex with TgMIC6-EGF2. The structure of the EGF domain within the complex shows a canonical EGF domain topology (Fig 2B), in which two double-stranded β-hairpins stack in a staggered arrangement that is fixed by the three disulphide bonds present within the core. The two β-hairpins from TgMIC6-EGF2 clamp onto one side of the β-sandwich from TgMIC1-GLD burying an intimate and large surface area at the interface (∼1450 Å2), which explains the high affinity of the complex. Gap volume index for the complex is 1.1 Å, indicating highly complementary interacting surfaces (Laskowski, 1995).

Figure 2.

Solution structure of the complex between TgMIC1-GLD and TgMIC6-EGF2. (A) Stereo diagram showing Cα traces representing the ensemble of nuclear magnetic resonance-derived structures (TgMIC1-GLD is shown in orange and TgMIC6-EGF2 is shown in green). (B) Ribbon representation of a representative structure for the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex (TgMIC1-GLD is shown in orange and TgMIC6-EGF2 is shown in green). Strand assignments are indicated. The orientation shown on the left is identical to that in (A), whereas the orientation shown on the right represents a 90° rotation about the y axis. (C) Stereo diagram showing an enlarged view of interface I from the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex illustrating crucial hydrophobic residues at the interface. (D) Stereo diagram showing an enlarged view of interface II from the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex. Residues are numbered for both TgMIC1-GLD and TgMIC6-EGF2 (labelled with quotes). EGF, epidermal growth factor-like; GLD, galectin-like domain; MIC, microneme proteins.

Although TgMIC1-GLD is in contact with many residues along the length of the TgMIC6-EGF2 sequence, two principal interfacial regions can be delineated. The first comprises Ala 82, Val 84, Ala 98 and Val 100 from β-strands H and I in TgMIC1-GLD, which forms an exposed hydrophobic surface on one of the large β-sheets (strands KBGHI; Fig 2B) and interacts with residues Ile 44, Leu 46 and Val 52 from the underside of the C-terminal β-hairpin from EGF2 (Fig 2C; interface I). A second important point of contact is presented by TgMIC1-GLD at one edge of the β-sandwich (Fig 2D; interface II). In the centre of this region are the hydrophobic residues Phe 49, Val 60 and Tyr 99 from TgMIC1-GLD, which form a binding pocket for Ile 35 from TgMIC6-EGF2 (Fig 2D). Classical antiparallel hydrogen bonding patterns are also observed between main chain atoms of the second β-strand (residues Cys 38, Cys 36 and Tyr 34) from the EGF domain and the edge of the KBGHI β-sheet (Ser 96, Ala 98 and Val 100 from strand I) to form a contiguous seven-stranded sheet.

To provide a complete structural insight into the mode of interaction, the high-resolution solution structure of TgMIC6-EGF2 in its unbound form was solved. Although the absence of principal rearrangements of secondary structure between the free and bound forms (r.m.s.d. of 1.8 and 1.4 Å over 102 and 41 Cα atoms within secondary structure elements of TgMIC1 and TgMIC6, respectively) supports a lock-and-key mode of interaction, several loop regions become more ordered on complex formation. For example, the disordered C terminus of TgMIC1-GLD (residues 128–137) provides a ‘latch' by folding back over the KBGHI β-sheet and making numerous intermolecular contacts with the EGF domain (supplementary Fig 2 online).

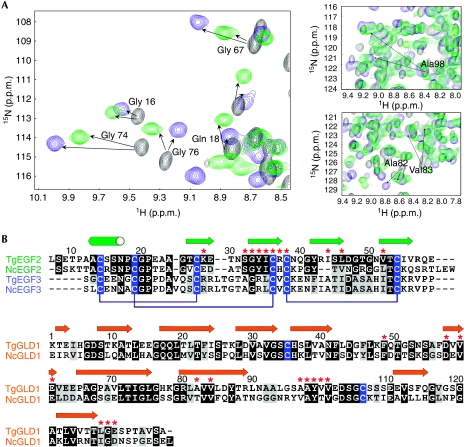

To propose a model for the assembly of mature, full-length forms of TgMIC1 and TgMIC6, we used NMR spectroscopy to establish whether TgMIC1-GLD binds to TgMIC6-EGF3 in the same mode as EGF2. Most of the TgMIC1 amides (>85%) experiencing chemical shift changes in the EGF2 complex are also perturbed when TgMIC1 is bound to EGF3 (Fig 3A). Furthermore, the amides showing the largest chemical shift changes, indicative of principal changes in the chemical environment as a result of binding, are of comparable magnitude in both complexes (supplementary Table II online). We also recorded an isotope 13C-filtered/edited nuclear Överhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) spectrum on a hybrid 13C–15N-labelled sample and confirmed several predicted intermolecular nuclear Överhauser effects (NOEs) based on the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex (supplementary Fig 3 online). Therefore, we conclude that the modes of recognition of the two EGF domains by TgMIC1 are analogous, consistent with a sequence alignment that shows a conservation of crucial interfacial residues between the two EGF domains (20% identity between TgEGF2 and TgEGF3; Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

MIC6 and MIC1 from Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum assemble in an analogous manner. (A) Regions of two-dimensional 1H–15N HSQC spectra for 13C–15N-labelled TgMIC1-GLD alone (black) and in the presence of unlabelled TgMIC6-EGF2 (green) or TgMIC6-EGF3 (blue) at a molar ratio of 1:1. Assignments for resonances experiencing large chemical shift deviations are labelled. (B) Sequence alignments for the EGF domains from TgMIC6 and from a putative MIC6 homologue from N. caninum (top), and for the GLD domains from TgMIC1 and NcMIC1 (bottom), including TgMIC6 (EGF2 aa 93–146, EGF3 aa 146–196, TgMIC1 (GLD aa 320–456) and NcMIC1 (GLD aa 323–460)). Cysteines are highlighted in blue and disulphide bond connectivities are indicated (brackets) for the EGF domains. Secondary structure elements are indicated above the sequence alignments; β-strands are shown as arrows and the α-helix is shown as a cylinder. Prominent interfacial side chains are indicated by red asterisks. EGF, epidermal growth factor-like; GLD, galectin-like domain; HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence; MIC, microneme protein.

EGF domains are often found in cell surface proteins where they are involved in protein–protein interactions that promote intercellular signalling, often in multivalent interactions to increase specificity. EGF domains are also present in other apicomplexan MICs and in several malarial surface proteins (Anantharaman et al, 2007). A notable example includes a homologue of TgMIC6 identified in the Neospora caninum genome sequence. The alignment of the EGF domains from these two sequences, together with the alignment of galectin-like domains from TgMIC1 and NcMIC1, shows a high degree of conservation at positions identified as crucial interacting residues in the MIC1–MIC6 complex, suggesting that an equivalent complex is assembled in N. caninum (Fig 3B). Further examples containing tandem repeats of EGF domains include TgMIC3, TgMIC7, TgMIC8 and TgMIC9 (Meissner et al, 2002b), MIC4 from Eimeria, Plasmodium falciparum Pfs25, which is expressed in zygotes and ookinetes, and the merozoite surface protein MSP1. Our structure for the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex provides the first structural insight into the recognition of the EGF domain at the surface of apicomplexans and might represent a generalized mode of interaction, in which the first β-hairpin of the EGF domain extends an intermolecular β-sheet and the second β-hairpin clamps the surface. It is conceivable that β-sheet-rich domains other than GLDs interact with EGF domains in a similar manner.

EGF2 and EGF3 promote host cell receptor recognition

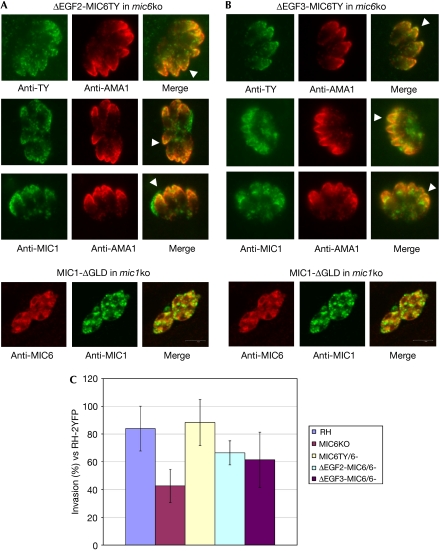

Our observation of two independent TgMIC1 interactions within TgMIC6 has profound consequences for the recognition of host cell receptors, as TgMIC1 is able to discriminate oligosaccharides in a highly specific manner (Blumenschein et al, 2007). To determine the relative importance of the twin TgMIC1-binding sites within TgMIC6, transport of the components of the complex was analysed by immunofluorescence assay in a mic6 knock out (ko) strain, as well as in mic6ko parasites complemented with constructs expressing full-length TgMIC6, TgMIC6-ΔEGF3 or TgMIC6-ΔEGF2. It has been shown previously that, in the absence of TgMIC6, TgMIC1 is mistargeted to the dense granules but that the expression of full-length TgMIC6 in the mic6ko background fully rescues the correct targeting of TgMIC1 to the micronemes (Reiss et al, 2001; Saouros et al, 2005a). Complementation of the mic6ko with either TgMIC6-ΔEGF3 or TgMIC6-ΔEGF2 also restores the transport of TgMIC1 to the micronemes (Fig 4A,B), suggesting that both TgMIC6 EGF domains are able to interact independently with TgMIC1 within the parasite. It has recently been shown for TgMIC3 that the minimal requirement for microneme delivery is the presence of its pro-peptide together with any one of the adjacent EGF domains (El Hajj et al, 2008). In other studies, it has been suggested that short α-helical segments are important for secretory organelle sorting (Dikeakos et al, 2007). Interestingly, our structural data show the presence of an α-helix within the amino terminus of TgMIC6-EGF2, which is immediately adjacent to the predicted TgMIC6-EGF1 cleavage site (Fig 1A); therefore, the subsequent exposure of the helix by the proteolytic removal of TgMIC6-EGF1 could reflect a biological signal that indicates the correct assembly of the complex and, in turn, allows correct targeting.

Figure 4.

Functional characterization of the mic6 knock out strain and mic6 knock out parasites complemented with either full-length TgMIC6 or ΔEGF2-MIC6TY and ΔEGF3-MIC6TY mutant proteins. Immunofluorescence assays showing that (A) ΔEGF2-MIC6TY and (B) ΔEGF3-MIC6TY are stably expressed and correctly targeted to the micronemes (anti-TY; green). Transport of TgMIC1 to the micronemes is partly restored in these parasites (anti-MIC1; green), as shown by colocalization with the microneme marker AMA1 (anti-AMA1; red). White arrowheads indicate examples of correct targeting to the micronemes. Note that ΔEGF2-MIC6TY is TY-tagged. A control assay is shown (bottom in A,B) in which MIC1-ΔGLD is unable to interact with either EGF domain from MIC6 and rescue correct microneme localization. TgMIC6 and TgMIC1 are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi and dense granules, respectively. A green/magenta version of this figure is shown as supplementary Fig 4 online. (C) Functional assay comparing various parasite strains for their invasion efficiency using RH-2YFP parasites as an internal standard for parasite fitness and human foreskin fibroblasts as host cells. Invasion data were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman–Keuls test. Invasion data for ΔEGF2-MIC6/6 and ΔEGF3-MIC6/6 parasites are statistically different from MIC6KO and RH-2YFP parasites, supporting the partial complementation of invasion activity in these mutants. ANOVA, analysis of variance; EGF, epidermal growth factor-like; GLD, galectin-like domain; ko, knock out; MIC, microneme protein; RH-2YFP, RH strain of Toxoplasma gondii transformed with a plasmid expressing yellow fluorescent protein.

To determine whether the mutant complexes in the TgMIC6-ΔEGF3 and TgMIC6-ΔEGF2 parasites are functional in invasion, we characterized the relative invasion efficiency of the mic6ko and the various complemented strains. The host cell invasion efficiency of the mic6ko strain was reduced to around 50% of the level of the parental RH strain (Fig 4C). Invasion efficiency was partly restored when the mic6ko strain was complemented with TgMIC6, TgMIC6-ΔEGF3 or TgMIC6-ΔEGF2, providing evidence that both EGF domains allow the presentation of TgMIC1 and recognition of host cell receptors for invasion (Fig 4C). Microneme targeting and subsequent invasion by the mutant parasites are not as efficient as with full-length TgMIC6, which most likely reflects the perturbed stoichiometry of the complex (Fig 4).

Speculation

Fig 5 shows a model of the relative arrangement of the two EGF domains based on a structural alignment with the tandem EGF domains from MSP1. Both TgMIC1-binding sites lie on opposite sides of the complex and are available for interaction, which projects the host cell-binding MAR domains of TgMIC1 and the associated TgMIC4 into the extracellular milieu. Previous results from carbohydrate microarray experiments have shown that the most potent binders of TgMIC1 were branched carbohydrates having two or more terminal sialic acids, which raised the possibility that tandem MAR regions provide highly specialized ligands for recognizing bidentate receptors (Blumenschein et al, 2007). Our new discovery extends this model for TgMIC4–1–6 complex function in that four receptor-binding sites could be presented through two branches of TgMIC1 molecules bound to one TgMIC6. This subunit multivalency is further reminiscent of the erythrocyte-binding antigen (EBA-175) from P. falciparum (Blumenschein et al, 2007; Hager & Carruthers, 2008), which is dimeric and comprises tandem Duffy-binding ligand domains that recognize several sialyl glycans (Tolia et al, 2005).

Figure 5.

A new model for the architecture of the TgMIC4–1–6 complex. A schematic representation of a model for the TgMIC4–1–6 complex illustrating the relative location of the domains and host cell-binding sites. The sialic acid-containing receptor(s) are shown as pink space-filling spheres. Colour code: yellow, apple domains; purple, microneme adhesive repeat (MAR) domain; orange, galectin-like domain (GLD); green and blue, second and third epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) domains; grey, transmembrane (TM); and red cylinder, acidic region. The six apple domains of TgMIC4 are represented as yellow circles, as no structural information is available. MIC, microneme protein.

Methods

Recombinant TgMIC1-GLD, TgMIC6-EGF2 (residues 87–147) and TgMIC6-EGF3 (residues 141–209) were expressed and purified as described previously (Saouros et al, 2005a, 2005b).

T. gondii mic6ko parasites, as well as the mic6ko-complemented stable parasite strains MIC6TY, MIC6-ΔEGF2 and MIC6-ΔEGF3, were obtained as described previously (Reiss et al, 2001). Indirect immunofluorescence assays were used to probe the transport of TgMIC6 and TgMIC1. Comparison of the various T. gondii strains for invasion efficiency was carried out using the RH strain transformed with a plasmid expressing yellow fluorescent protein (RH-2YFP) as the internal standard.

The interaction between TgMIC1-GLD and either TgMIC6-EGF2 or TgMIC6-EGF3 was probed using two-dimensional 1H–15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR mapping experiments, gel filtration chromatography and isothermal titration calorimetry.

For the structural determination, NMR spectra on the complex were recorded on hybrid labelled samples of 15N, 13C- or 14N, 12C-TgMIC1-GLD (residues 320–456 in the full-length TgMIC1 sequence) and 14N, 12C- or 15N, 13C-TgMIC6-EGF2 (residues 87–147 in the full-length TgMIC6 sequence). Backbone and side-chain assignments were completed using standard methodology (Sattler et al, 1999). Intermolecular NOE identification was aided by filtered (12C,14N)H-NOESY–13C-HSQC experiments (Zwahlen et al, 1997). Coordinates for the NMR structures of unbound TgMIC6-EGF2 and the TgMIC1-GLD–TgMIC6-EGF2 complex have been deposited at the Protein Databank under the accession codes 2K2T and 2K2S. For detailed descriptions, see the supplementary information online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to our friend and colleague Laurent Bonomo, who died in July 2008. This study was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC grant numbers G0400423 and G0800038, S.M.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant number E02520X, S.J.M.) and Swiss National Foundation (31-116722, D.S.-F.). This study is part of the activities of the BioMalPar European Network of Excellence supported by a European grant (LSHP-CT-2004-503578). K.S. identified the TgMIC1–TgMIC6-EGF2 interaction and carried out all MIC6-related structural work; S.S. carried out all MIC1-related structural work; and N.F. carried out the localization and invasion assays.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Anantharaman V, Iyer LM, Balaji S, Aravind L (2007) Adhesion molecules and other secreted host-interaction determinants in apicomplexa: insights from comparative genomics. Int Rev Cytol 262: 1–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenschein TM et al. (2007) Atomic resolution insight into host cell recognition by Toxoplasma gondii. EMBO J 26: 2808–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht S, Carruthers VB, Ferguson DJP, Giddings OK, Wang G, Jakle U, Harper JM, Sibley LD, Soldati D (2001) The Toxoplasma micronemal protein MIC4 is an adhesin composed of six conserved apple domains. J Biol Chem 276: 4119–4127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers VB, Giddings OK, Sibley LD (1999) Secretion of micronemal proteins is associated with Toxoplasma invasion of host cells. Cell Microbiol 1: 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikeakos JD, Lacombe M-J, Mercure C, Mireuta M, Reudelhuber TL (2007) A hydrophobic patch in a charged α-helix is sufficient to target proteins to dense core secretory granules. J Biol Chem 282: 1136–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey JP (2004) Toxoplasmosis—a waterborne zoonosis. Vet Parasitol 126: 57–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj H, Papoin J, Cérède O, Garcia-Réguet N, Soête M, Dubremetz JF, Lebrun M (2008) Molecular signals in the trafficking of the Toxoplasma gondii protein MIC3 to the micronemes. Eukaryot Cell 7: 1019–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco G, Rinaldi L, Guarino A, Proroga YTR, Pesce A, Giuseppina DM, Cringoli G (2007) Toxoplasma gondii in sheep from the Campania region (Italy). Vet Parasitol 149: 271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager KM, Carruthers VB (2008) MARveling at parasite invasion. Trends Parasitol 24: 51–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, Dubey JP (2002) Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin Microbiol Infect 8: 634–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett TJ, Sibley LD (2003) Aldolase forms a bridge between cell surface adhesins and the actin cytoskeleton in apicomplexan parasites. Mol Cell 11: 885–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA (1995) SURFNET: a program for visualizing molecular surfaces, cavities, and intermolecular interactions. J Mol Graph 13: 323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M, Schluter D, Soldati D (2002a) Role of Toxoplasma gondii myosin A in powering parasite gliding and host cell invasion. Science 298: 837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M, Reiss M, Viebig N, Carruthers VB, Toursel C, Tomavo S, Ajioka JW, Soldati D (2002b) A family of transmembrane microneme proteins of Toxoplasma gondii contain EGF-like domains and function as escorters. J Cell Sci 115: 563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Viebig N, Brecht S, Fourmaux MN, Soete M, Di Cristina M, Dubremetz JF, Soldati D (2001) Identification and characterization of an escorter for two secretory adhesins in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Biol 152: 563–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saouros S et al. (2005a) A novel galectin-like domain from Toxoplasma gondii micronemal protein 1 assists the folding, assembly and transport of a cell-adhesion complex. J Biol Chem 280: 38583–38591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saouros S, Chen HA, Simpson P, Cota E, Edwards-Jones B, Soldati-Favre D, Matthews S (2005b) Complete resonance assignments of the C-terminal domain from MIC1: a micronemal protein from Toxoplasma gondii. J Biomol NMR 31: 177–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M, Schleucher J, Griesinger C (1999) Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog NMR Spectrosc 34: 93–158 [Google Scholar]

- Soldati D, Meissner M (2004) Toxoplasma as a novel system for motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolia NH, Enemark EJ, Sim BKL, Joshua-Tor L (2005) Structural basis for the EBA-175 erythrocyte invasion pathway of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell 122: 183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwahlen C, Legault P, Vincent SJF, Greenblatt J, Konrat R, Kay LE (1997) Methods for measurement of intermolecular NOEs by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to a bacteriophage λ N-peptide/boxB RNA complex. J Am Chem Soc 119: 6711–6721 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information