Abstract

Recent progress in global sequence and microarray data analysis has revealed the increasing complexity of the human transcriptome. Alternative splicing generates a huge diversity of transcript variants and disruption of splicing regulatory networks is emerging as an important contributor to various diseases, including cancer. Current efforts to establish the dynamic repertoire of transcripts that are generated in health and disease are showing that many cancer-associated alternative-splicing events occur in the absence of mutations in the affected genes. A growing body of evidence reveals changes in splicing-factor expression that correlate with cancer development, progression and response to therapy. Here, we discuss how recent links between cancer and altered expression of proteins implicated in splicing regulation are bringing the splicing machinery to the fore as a potential target for anticancer treatment.

Keywords: cancer, pre-mRNA splicing, spliceosome, receptor, splicing factor, therapeutic target

Glossary

BCL-X BCL-2-like 1 protein, an apoptosis regulator; alternative splicing of the BCL-X precursor messenger RNA gives rise to two isoforms encoding proteins with antagonistic functional properties, a long antiapoptotic isoform and a short proapoptotic isoform

BIN1 bridging integrator 1, a tumour-suppressor gene that is involved in apoptosis; the appearance of splicing factor 2/alternative splicing factor-dependent BIN1 splicing isoforms correlates with decreased levels of apoptosis

CDC25B cell-division cycle 25B

FAS an apoptosis-stimulating fragment, also known as member 6 of the tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily; the human FAS gene encodes a transmembrane protein that mediates apoptosis upon ligation of the FAS ligand; alternative splicing produces either a membrane bound form of the receptor that promotes apoptosis or a soluble isoform that prevents programmed cell death

MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase

MNK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2; as a result of splicing factor 2/alternative splicing factor-dependent alternative splicing, the MNK2 kinase is active in the absence of upstream signals from the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway

MRP1 multidrug resistance-associated protein 1

pre-mRNA precursor messenger RNA, the initial transcript of a protein-coding gene

PTB polypyrimidine-tract binding protein, involved in splicing regulation

RBM5 RNA-binding motif protein 5, involved in splicing regulation

RNAi RNA interference

RON recepteur d'origine nantais; the RON protein belongs to the mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor proto-oncogene family of receptor tyrosine kinases

S6K1 ribosomal protein S6 kinase, involved in translational control in the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway; overexpression of splicing factor 2/alternative splicing factor induces alternative splicing of S6K1 leading to a protein isoform with oncogenic properties

SF2/ASF splicing factor 2/alternative splicing factor, a member of the serine/arginine rich protein family; participates in constitutive and alternative splicing, and is essential for cell viability

SF3b splicing factor 3b, an integral component of the U2 small-nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle

siRNA small interfering RNA

snRNPs small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles, the building blocks of the spliceosome; each is composed of a uridine-rich small-nuclear RNA packaged with proteins

SPF45/RBM17 45 kDa-splicing factor/RNA-binding motif protein 17, involved in splicing regulation

SRP20 a member of the serine/arginine rich protein family, involved in splicing regulation

SRPK serine/arginine rich protein kinase

U2AF U2 small-nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle auxiliary factor is an essential splicing factor composed of two subunits, U2AF65 and U2AF35; U2AF35 assists binding of U2AF65 to the polypyrimidine tract upstream of the 3′ splice site, which promotes recruitment of the U2AF to the precursor messenger RNA

Introduction

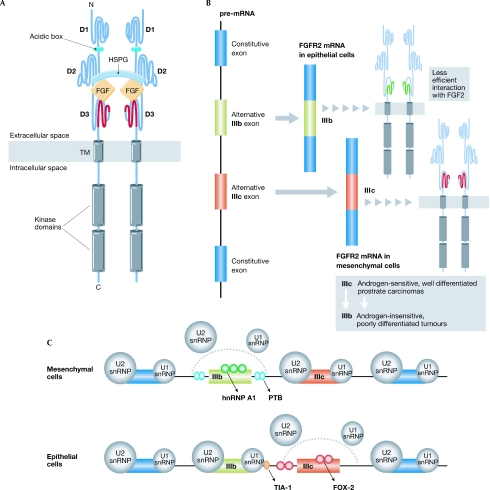

Removal of noncoding sequences (introns) from pre-messenger RNAs through splicing provides a versatile means of genetic regulation. Alternative splicing allows a single gene to generate multiple transcripts, thereby expanding the transcriptome and proteome diversity in metazoans. Several studies based on large-scale expressed sequence tag analysis estimated that more than 60% of human genes undergo alternative splicing; this number recently increased to more than 80% when microarray data became available (Black, 2003; Matlin et al, 2005). Intron excision is carried out by an assembly of snRNPs and extrinsic, non-snRNP, protein-splicing factors that are collectively recruited to pre-mRNAs and form the spliceosome. The initial events of spliceosome assembly require the recognition of specific sequences located at, and near, the 5′ and 3′ splice sites, which recruit the U1 and U2 snRNPs (Fig 1). In metazoan organisms, the splice-site sequences are weakly conserved, and require specific additional RNA sequence elements that function either to enhance or to repress the ability of the spliceosome to recognize and select nearby splice sites (Maniatis & Tasic, 2002; Matlin et al, 2005). The multiplicity of protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions that modulate the association of the spliceosome with the pre-mRNA constitutes the basis for the control of alternative splicing (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Alternative splicing of FGFR2. (A) FGF signalling is mediated by four FGFR tyrosine kinases known as FGFR1–4, which have crucial roles in morphogenesis, development, angiogenesis and wound healing. FGFRs are composed of an extracellular ligand-binding portion consisting of three immunoglobulin-like domains (D1, D2 and D3), a single transmembrane (TM) helix and a cytoplasmic portion that contains protein tyrosine kinase activity. Ligand binding and specificity reside in D2, D3 and the linker that connects them. Alternative splicing in the carboxy-terminal half of D3 is an important determinant of FGF–FGFR binding specificity. (B) The transcripts (pre-mRNA) encoding FGFR2 contain two alternative exons: IIIb and IIIc. Inclusion of exon IIIb instead of exon IIIc introduces an amino-acid sequence in the second half of D3 that is less likely to form the hydrophobic core required for efficient interaction with FGF2 (Plotnikov et al, 2000). Inclusion of exon IIIb occurs predominantly in epithelial cells, whereas inclusion of exon IIIc is exclusively detected in cells of mesenchymal origin. A switch from exon IIIb to exon IIIc inclusion accompanies the progression of androgen-sensitive, well-differentiated prostate carcinomas to androgen-insensitive, poorly differentiated tumours (Carstens et al, 1997; Yan et al, 1993). (C) In mesenchymal cells, exon IIIb silencing depends on the combined effect of weak splice sites, an exonic splicing silencer that binds hnRNP A1, and two flanking intronic splicing silencers that bind to PTB. The binding of hnRNP A1 and PTB to the splicing silencers inhibits the recruitment of U1 and U2 snRNPs to the weak splice sites of exon IIIb. In epithelial cells, exon IIIb silencing is countered by binding of TIA-1 to an intronic activating sequence located downstream of exon IIIb. TIA-1 binding promotes the recruitment of U1 snRNP to the weak 5′ splice site of exon IIIb. In addition, FOX-2 binds to intronic and exonic (U)GCAUG sequence elements, and contributes to both exon IIIb activation and exon IIIc repression. FOX-2 proteins are differentially expressed in IIIb+ cells in comparison to IIIc+ cells, and overexpression of FOX-2 is sufficient to induce a switch in splice choice from IIIc to IIIb (Baraniak et al, 2006 and references therein). FGF fibroblast growth factor; FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2; FOX-2 forkhead box-2; hnRNP heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticle; HSPG, heparan sulphate proteoglycan; PTB, polypyrimidine-tract binding protein; snRNP, small-nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle; TIA-1, cytotoxic granule-associated RNA binding protein.

A typical multiexon pre-mRNA can undergo various alternative-splicing patterns (Black, 2003). Most exons are constitutive, meaning that they are always included in the final mRNA; however, there are also regulated exons, which are sometimes included and sometimes excluded from the mRNA (Fig 1). Exons can also be lengthened or shortened by altering the position of one of their splice sites, or by a distinct splicing pattern that consists of failure to remove an intron, a process known as intron retention. Alternative splicing can also be coupled to differential promoter or polyadenylation site usage, giving rise to even larger transcriptome heterogeneity. Splicing abnormalities have an important role in human diseases such as cancer (Wang & Cooper, 2007). Several mutations are known to affect the splicing of oncogenes, tumour suppressors and other cancer-relevant genes (Srebrow & Kornblihtt, 2006; Venables, 2006); however, many splicing abnormalities that have been identified in cancer cells are not associated with mutations in the affected genes. Rather, a growing body of evidence indicates that the splicing machinery is an important target for misregulation in cancer. According to recent bioinformatics studies, changes in splicing-factor expression might have a key role in the general splicing disruption that occurs in many cancers (Kim et al, 2008; Ritchie et al, 2008).

Can splicing factors act as oncogenes?

As changes in the concentration, localization and/or activity of splicing factors are known to modify the selection of splice sites (Matlin et al, 2005), it is predicted that the abnormally expressed splicing factors found in tumour cells induce the production of mRNA isoforms that are either nonexistent or less abundant in normal cells. This phenomenon might contribute directly or indirectly to cancer development, progression and/or response to therapy. A recent study demonstrated for the first time that overexpression of a splicing factor can, indeed, trigger malignant transformation (Karni et al, 2007). The authors showed that the splicing factor SF2/ASF is upregulated in various human tumours, and affects alternative splicing of the tumour suppressor BIN1 and the kinases MNK2 and S6K1. The resulting BIN1 isoforms lack tumour-suppressor activity, the MNK2 isoform promotes MAPK-independent eIF4E phosphorylation and the S6K1 isoform has demonstrated oncogenic properties (Karni et al, 2007). This study acts as a proof-of-principle and provides evidence that abnormally expressed splicing proteins can have oncogenic properties.

A previous study had indicated that SF2/ASF affects alternative splicing of RON, which is a tyrosine kinase receptor involved in cell dissociation, motility and matrix invasion (Ghigna et al, 2005). An alternatively spliced isoform of RON that lacks exon 11 produces a constitutively active protein that is expressed in gastric, breast and colon cancers, and induces an invasive phenotype (Collesi et al, 1996; Ghigna et al, 2005). Binding of SF2/ASF to a regulatory sequence in exon 12 stimulates skipping of exon 11, and overexpression of SF2/ASF activates cell locomotion. This effect can be reversed by specific knockdown of the alternatively spliced RON isoform, suggesting that an upregulation of SF2/ASF could contribute to malignant transformation by inducing alternative splicing of RON.

Several additional splicing proteins have been shown to be upregulated in various human tumours (Table 1); however, in most cases, the effect that these changes have on splicing regulation is unknown. By contrast, the number of splicing proteins that have been shown to be downregulated in cancer is much lower (Table 1). For example, reduced expression of U2AF was found in pancreatic cancer cells and correlated with mis-splicing of the cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor mRNA (Ding et al, 2002). Furthermore, RNAi-mediated downregulation of U2AF in HeLa cells has been reported to alter the ratios of alternatively spliced isoforms of transcripts encoding the oncogenic CDC25B phosphatase, and to increase the level of CDC25B protein (Pacheco et al, 2006).

Table 1.

Splicing factors altered in cancer and potential splicing targets

| Name (alternative names) | Cancer tissue | Affected mRNA | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated in cancer | ||||

| SR and AR-related proteins | SF2/ASF (SFRS1) | Colon, thyroid, small intestine, kidney, lung, breast and colon | RON, BIN1, S6K1, MNK2 | Ghigna et al, 2005; Karni et al, 2007 |

| SC35 (SFRS2) | Ovary | – | Fischer et al, 2004; Xiao et al, 2007 | |

| SRp20 (SFRS3) | Ovary | MRP1 | He et al, 2004 | |

| SRp40 (SFRS5) | Breast | CD44 | Huang et al, 2007 | |

| SRp55 (SFRS6) | Breast | – | Karni et al, 2007 | |

| TRA2-β1 (SFRS10) | Breast | CD44 | Watermann et al, 2006 | |

| SRm160 (SRRM1) | Thymic epithelium, stomach and kidney | CD44 | Cheng & Sharp, 2006; Harn et al, 1996; Lee et al, 2003; Wu et al, 2003 | |

| hnRNP proteins | hnRNP A1 (HNRNPA1) | Lung, breast and ovary | – | Patry et al, 2003; Zerbe et al, 2004 |

| hnRNP B1 (HNRNPA2B1) | Lung | – | Sueoka et al, 2001; Zhou et al, 1996 | |

| hnRNP F (HNRNPF) | Colon | – | Balasubramani et al, 2006 | |

| hnRNP L (HNRNPL) | Oesophageal cancer cell lines | – | Qi et al, 2008 | |

| hnRNP K (HNRNPK) | Colorectal and oral | – | Carpenter et al, 2006; Roychoudhury & Chaudhuri, 2007 | |

| PTB (PTBP1, HNRNPI) | Glioblastoma and ovary | FGFR1, MRP1 | Jin et al, 2003; He et al, 2004 | |

| Other factors | YB-1 (YBX1) | Ovary | CD44 | Fischer et al, 2004 |

| SPF45 (RBM17) | Bladder, breast, colon, lung, ovary, pancreas and prostate | FAS | Corsini et al, 2007; Sampath et al, 2003 | |

| SRPK1 (SFRSK1) | Pancreas, breast, colon, T cells and chronic myelogenous leukaemia | MAP2K2 | Hayes et al, 2006 | |

| HuR (ELAVL1) | Breast and ovary | FAS | Denkert et al, 2004; Izquierdo, 2008 | |

| HuD (ELAVL4) | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | IK | Bellavia et al, 2007 | |

| Sam68 (KHDRBS1) | Prostate | – | Busa et al, 2007 | |

| Downregulated in cancer | ||||

| hnRNP | hnRNP E2 (PCBP2) | Oral | – | Roychoudhury & Chaudhuri, 2007 |

| Other factors | U2AF35 (U2AF1) | Pancreas | CCK-B | Ding et al, 2002; Pacheco et al, 2006 |

| SF1 (Sf1) | Colorectal | WISP1, FGFR3 | Shitashige et al, 2007a,b | |

| RBM5 (LUCA15) | Lung | – | Oh et al, 2006 |

BIN1, bridging integrator 1; CCK-B, cholecystokinin-B/gastrin; FAS, apoptosis-stimulating fragment; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticle; HuD, Hu antigen D; HuR, Hu antigen R; IK, transcription factor Ikaros; MAP2K2, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MNK2, mitogen-activated protein kinase-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2; mRNA, messenger RNA; MRP1, multidrug-resistance protein 1; PTB, polypyrimidine-tract binding protein; RBM5, RNA-binding motif protein 5; Ron, recepteur d'origine nantais; S6K1, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; Sam68, Src-associated in mitosis 68 kDa; SC35, splicing component 35 kDa; SF, splicing factor; SFR, splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich; SF2/ASF, splicing factor 2/alternative splicing factor; SPF45, 45 kDa-splicing factor; SR, serine/arginine rich; SRm160, serine/arginine-related nuclear matrix protein; SRp, serine/arginine rich protein; SRPK, serine/arginine rich protein kinase; Tra2-β1, human homologue of Drosophila splicing regulator Transformer 2; U2AF, U2 small-nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle auxiliary factor; WISP, wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 1-inducible signalling pathway protein 1; YB-1, Y-box binding protein 1.

In conclusion, there is a growing list of splicing factors that have been found to be upregulated or downregulated in cancers, as compared with the corresponding normal tissues. Nevertheless, in most cases the available data are strictly correlative. A challenge for the future will be to determine whether these changes contribute directly to the cancer phenotype, or whether they are simply among the many processes that are altered in cancer cells. A crucial issue is whether cells expressing abnormal levels of certain splicing factors are positively selected for during tumour progression, as misregulated splicing factors might generate splice variants encoding protein isoforms that provide advantages to these cells, such as increased proliferation, anti-apoptotic or pro-angiogenic effects, enhanced cell motility or tumour-cell survival. Moreover, many RNA-binding proteins are multifunctional and their abnormal expression might have oncogenic effects that are independent from splicing. What triggers the upregulation and downregulation of splicing proteins is also unknown (Sidebar A). Consistent with the view that cancer-associated genetic instability is likely to have an important role in this process, overexpression of splicing factor SF2/ASF was shown to associate with amplification of the gene encoding it (Karni et al, 2007), whereas reduced expression of RBM5 in lung cancer correlates with deletion of its gene locus at chromosomal region 3p21.3 (Oh et al, 2006). Alternatively, or in addition, splicing-factor transcripts seem to be preferential targets for disrupted splicing in cancer tissues (Kim et al, 2008; Ritchie et al, 2008). Cancer-specific splicing-factor isoforms could either alter the function of the protein in the cell or reduce its level owing to the introduction of premature stop codons, thereby leading to nonsense-mediated decay of the mRNA.

Sidebar A | In need of answers.

The precise mechanism underlying the induction of malignant transformation by splicing-factor overexpression remains unknown. The current working model postulates that changes in splicing-factor expression induce a switch in splice choice from target messenger RNAs, and that this, in turn, leads to production of new splicing variants with oncogenic properties.

What triggers the upregulation and downregulation of splicing proteins in tumours?

The ultimate remaining challenge is to integrate the different layers of gene-expression regulation that are disrupted in cancer and construct a systems view for the molecular pathology of this disease.

Splicing factors and anticancer therapy

During the past 20 years, anticancer drug development has focused on targeted medicines that are more specifically associated with tumour cells than conventional cytotoxic drugs. More than 600 new agents are now in the development pipeline, in the hope of attaining greater anticancer activity with fewer side effects (Dancey & Chen, 2006). Several approaches are being explored for the correction of cancer-associated splicing abnormalities that are still at the preclinical stage (for comprehensive reviews, see Pajares et al, 2007; Wang & Cooper, 2007). One strategy uses synthetically modified oligonucleotides that are able to block spliceosome assembly at specific sites, thereby preventing the generation of cancer-associated splice variants. This approach has been successfully used to shift the ratio of anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic proteins produced by alternative splicing of the BCL-X gene, thereby sensitizing refractory cancer cells to undergo apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic drug treatment (Taylor et al, 1999). Another strategy that is being explored consists of raising antibodies against epitopes that are uniquely present in the cancer-associated protein isoforms and conjugating the antibodies to tumour-cell toxins. For example, human recombinant antibodies specific to the alternatively spliced domains of tenascin-C large isoform—an abundant glycoprotein of the cancer extracellular matrix that is largely undetectable in normal adult tissues—have shown promising tumour-targeting properties (Brack et al, 2006).

Strategies aimed at targeting components of the splicing machinery that are abnormally expressed in cancer are expected to be less specific because they are likely to impinge on splicing regulation in normal cells. Nevertheless, many approaches have been attempted with encouraging results. Particular attention has been devoted to the development of protein kinase inhibitors that modulate the activity of splicing factors containing RS domains, which are characterized by repeats of arginine–serine dipeptides. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of these serine residues is thought to act as a switch that modulates the binding properties of these kinases to both RNA and proteins (Singh & Valcarcel, 2005). Although there are several known splicing-factor kinases, members of the SRPK family seem to be the most relevant in cancer (Table 1). Downregulation of SRPK1 expression by siRNA in cancer cell lines caused a reduction of cell proliferation, and increased sensitivity to gemcitabine and cisplatin, making the approach of targeting SRPK1 a promising tool that might prove to be therapeutically effective for tumours that overexpress this protein (Hayes et al, 2006, 2007).

In addition, the aberrant expression of splicing factors in tumour cells might be implicated in resistance to drugs that are commonly used in cancer therapy. For example, increased expression of the splicing factors PTB and SRP20 in ovarian cancer correlates with the production of alternatively spliced isoforms of MRP1, which confers increased resistance to doxorubicin (He et al, 2004). Another splicing factor that is highly expressed in numerous carcinomas, SPF45 (RBM17), affects the alternative splicing of the apoptosis regulator FAS (Corsini et al, 2007), and the overexpression of SPF45 has been implicated in resistance to doxorubicin and vincristine (Sampath et al, 2003).

It is fully anticipated that inhibiting the function of either a splicing kinase or a splicing protein will have a pleiotropic effect, as it will alter the splicing of numerous gene products in both cancerous and normal cells. However, a well-established principle of cancer therapy is to use a combination of drugs with various mechanisms of action and resistance, at their optimal doses and according to schedules that are compatible with normal cell recovery. Therefore, it might be possible to develop and to optimize agents that temporarily inhibit a splicing regulator and partly correct abnormal splicing, resulting in enhanced tumour-cell killing by chemotherapeutic drugs.

Recently, proof-of-principle has been provided for the development of anti-tumour compounds that target the splicing machinery. Spliceostatin A (Kaida et al, 2007) and pladienolide (Kotake et al, 2007), which are two potent inhibitors of cycling cancer cells, target the essential splicing protein SF3b and inhibit the splicing of several transcripts. Both drugs are only mildly toxic to animals and a pladienolide derivative, E7107, has already progressed to clinical trials. This moderate toxicity is probably due to partial inhibition of splicing throughout the organism; however, the mechanism behind the enhanced vulnerability of cancer cells to these drugs remains unknown. Most importantly, these studies have defined a new mode of action of anticancer drugs and identified a ubiquitous core component of the U2 snRNP, SF3b, as a valuable new therapeutic target.

Conclusion

The rapid development and increasing availability of novel genome-wide tools will soon provide a catalogue of all splicing factors and all splice variants that are differentially expressed in specific cancer types and the corresponding normal tissues. Irrespective of whether changes in splicing have a direct causative role in cancer, or act as modifiers or susceptibility factors in the oncogenic process, the identification of splicing signatures is likely to provide important markers for diagnosis, prognosis and/or sensitivity to treatment. A full description of all components of the splicing machinery and splicing events altered in cancer will also identify potential new targets for therapeutic approaches. However, the most challenging goal for the future will be to integrate the different layers of gene-expression regulation altered in cancer and to acquire a systems-biology view of the many molecular mechanisms that contribute to the pathophysiology of this disease.

From left: Maria Carmo-Fonseca, Sandra Martins & Ana Rita Grosso

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleague João Ferreira for stimulating discussions. Our laboratory is supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Portugal, and the European Commission (LSHG-CT-2005-518238, European Alternative Splicing Network). A.R.G. is supported by a Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia fellowship (SFRH/BD/22825/2005).

References

- Balasubramani M, Day BW, Schoen RE, Getzenberg RH (2006) Altered expression and localization of creatine kinase B, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F, and high mobility group box 1 protein in the nuclear matrix associated with colon cancer. Cancer Res 66: 763–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraniak AP, Chen JR, Garcia-Blanco MA (2006) Fox-2 mediates epithelial cell-specific fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 exon choice. Mol Cell Biol 26: 1209–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia D, Mecarozzi M, Campese AF, Grazioli P, Talora C, Frati L, Gulino A, Screpanti I (2007) Notch3 and the Notch3-upregulated RNA-binding protein HuD regulate Ikaros alternative splicing. EMBO J 26: 1670–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL (2003) Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 291–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack SS, Silacci M, Birchler M, Neri D (2006) Tumor-targeting properties of novel antibodies specific to the large isoform of tenascin-C. Clin Cancer Res 12: 3200–3208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busa R, Paronetto MP, Farini D, Pierantozzi E, Botti F, Angelini DF, Attisani F, Vespasiani G, Sette C (2007) The RNA-binding protein Sam68 contributes to proliferation and survival of human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 26: 4372–4382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B, McKay M, Dundas SR, Lawrie LC, Telfer C, Murray GI (2006) Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is over expressed, aberrantly localised and is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 95: 921–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens RP, Eaton JV, Krigman HR, Walther PJ, Garcia-Blanco MA (1997) Alternative splicing of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGF-R2) in human prostate cancer. Oncogene 15: 3059–3065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Sharp PA (2006) Regulation of CD44 alternative splicing by SRm160 and its potential role in tumor cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol 26: 362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collesi C, Santoro MM, Gaudino G, Comoglio PM (1996) A splicing variant of the RON transcript induces constitutive tyrosine kinase activity and an invasive phenotype. Mol Cell Biol 16: 5518–5526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini L, Bonnal S, Bonna S, Basquin J, Hothorn M, Scheffzek K, Valcarcel J, Sattler M (2007) U2AF-homology motif interactions are required for alternative splicing regulation by SPF45. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 620–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey JE, Chen HX (2006) Strategies for optimizing combinations of molecularly targeted anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5: 649–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkert C, Weichert W, Winzer KJ, Muller BM, Noske A, Niesporek S, Kristiansen G, Guski H, Dietel M, Hauptmann S (2004) Expression of the ELAV-like protein HuR is associated with higher tumor grade and increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 10: 5580–5586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WQ, Kuntz SM, Miller LJ (2002) A misspliced form of the cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor in pancreatic carcinoma: role of reduced cellular U2AF35 and a suboptimal 3′-splicing site leading to retention of the fourth intron. Cancer Res 62: 947–952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DC, Noack K, Runnebaum IB, Watermann DO, Kieback DG, Stamm S, Stickeler E (2004) Expression of splicing factors in human ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep 11: 1085–1090 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigna C, Giordano S, Shen H, Benvenuto F, Castiglioni F, Comoglio PM, Green MR, Riva S, Biamonti G (2005) Cell motility is controlled by SF2/ASF through alternative splicing of the Ron protooncogene. Mol Cell 20: 881–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harn HJ, Ho LI, Shyu RY, Yuan JS, Lin FG, Young TH, Liu CA, Tang HS, Lee WH (1996) Soluble CD44 isoforms in serum as potential markers of metastatic gastric carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 22: 107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes GM, Carrigan PE, Beck AM, Miller LJ (2006) Targeting the RNA splicing machinery as a novel treatment strategy for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res 66: 3819–3827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes GM, Carrigan PE, Miller LJ (2007) Serine-arginine protein kinase 1 overexpression is associated with tumorigenic imbalance in mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast, colonic, and pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res 67: 2072–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Ee PL, Coon JS, Beck WT (2004) Alternative splicing of the multidrug resistance protein 1/ATP binding cassette transporter subfamily gene in ovarian cancer creates functional splice variants and is associated with increased expression of the splicing factors PTB and SRp20. Clin Cancer Res 10: 4652–4660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CS, Shen CY, Wang HW, Wu PE, Cheng CW (2007) Increased expression of SRp40 affecting CD44 splicing is associated with the clinical outcome of lymph node metastasis in human breast cancer. Clin Chim Acta 384: 69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo JM (2008) Hu antigen R (HuR) functions as an alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulator of Fas apoptosis-promoting receptor on exon definition. J Biol Chem 283: 19077–19084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Bruno IG, Xie TX, Sanger LJ, Cote GJ (2003) Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein down-regulates fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 α-exon inclusion. Cancer Res 63: 6154–6157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida D et al. (2007) Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nat Chem Biol 3: 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni R, de Stanchina E, Lowe SW, Sinha R, Mu D, Krainer AR (2007) The gene encoding the splicing factor SF2/ASF is a proto-oncogene. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 185–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goren A, Ast G (2008) Insights into the connection between cancer and alternative splicing. Trends Genet 24: 7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake Y, Sagane K, Owa T, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shimizu H, Uesugi M, Ishihama Y, Iwata M, Mizui Y (2007) Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nat Chem Biol 3: 570–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Harn HJ, Lin TS, Yeh KT, Liu YC, Tsai CS, Cheng YL (2003) Prognostic significance of CD44v5 expression in human thymic epithelial neoplasms. Ann Thorac Surg 76: 213–218; Discussion 218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Tasic B (2002) Alternative pre-mRNA splicing and proteome expansion in metazoans. Nature 418: 236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW (2005) Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 386–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JJ, Razfar A, Delgado I, Reed RA, Malkina A, Boctor B, Slamon DJ (2006) 3p21.3 tumor suppressor gene H37/Luca15/RBM5 inhibits growth of human lung cancer cells through cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res 66: 3419–3427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco TR, Moita LF, Gomes AQ, Hacohen N, Carmo-Fonseca M (2006) RNA interference knockdown of hU2AF35 impairs cell cycle progression and modulates alternative splicing of Cdc25 transcripts. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4187–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares MJ, Ezponda T, Catena R, Calvo A, Pio R, Montuenga LM (2007) Alternative splicing: an emerging topic in molecular and clinical oncology. Lancet Oncol 8: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patry C, Bouchard L, Labrecque P, Gendron D, Lemieux B, Toutant J, Lapointe E, Wellinger R, Chabot B (2003) Small interfering RNA-mediated reduction in heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticule A1/A2 proteins induces apoptosis in human cancer cells but not in normal mortal cell lines. Cancer Res 63: 7679–7688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov AN, Hubbard SR, Schlessinger J, Mohammadi M (2000) Crystal structures of two FGF–FGFR complexes reveal the determinants of ligand-receptor specificity. Cell 101: 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi YJ, He QY, Ma YF, Du YW, Liu GC, Li YJ, Tsao GS, Ngai SM, Chiu JF (2008) Proteomic identification of malignant transformation-related proteins in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cell Biochem 104: 1625–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie W, Granjeaud S, Puthier D, Gautheret D (2008) Entropy measures quantify global splicing disorders in cancer. PLoS Comput Biol 4: e1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhury P, Chaudhuri K (2007) Evidence for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K overexpression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 97: 574– 575; author reply 576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath J et al. (2003) Human SPF45, a splicing factor, has limited expression in normal tissues, is overexpressed in many tumors, and can confer a multidrug-resistant phenotype to cells. Am J Pathol 163: 1781–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitashige M, Naishiro Y, Idogawa M, Honda K, Ono M, Hirohashi S, Yamada T (2007) Involvement of splicing factor-1 in β-catenin/T-cell factor-4-mediated gene transactivation and pre-mRNA splicing. Gastroenterology 132: 1039–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitashige M, Satow R, Honda K, Ono M, Hirohashi S, Yamada T (2007) Increased susceptibility of Sf1+/− mice to azoxymethane-induced colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Sci 98: 1862–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Valcarcel J (2005) Building specificity with nonspecific RNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebrow A, Kornblihtt AR (2006) The connection between splicing and cancer. J Cell Sci 119: 2635–2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka E, Sueoka N, Goto Y, Matsuyama S, Nishimura H, Sato M, Fujimura S, Chiba H, Fujiki H (2001) Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein B1 as early cancer biomarker for occult cancer of human lungs and bronchial dysplasia. Cancer Res 61: 1896–1902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JK, Zhang QQ, Wyatt JR, Dean NM (1999) Induction of endogenous Bcl-xS through the control of Bcl-x pre-mRNA splicing by antisense oligonucleotides. Nat Biotechnol 17: 1097–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP (2006) Unbalanced alternative splicing and its significance in cancer. Bioessays 28: 378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Cooper TA (2007) Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nat Rev Genet 8: 749–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watermann DO, Tang Y, Zur Hausen A, Jager M, Stamm S, Stickeler E (2006) Splicing factor Tra2-β1 is specifically induced in breast cancer and regulates alternative splicing of the CD44 gene. Cancer Res 66: 4774–4780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ST, Sun GH, Hsieh DS, Chen A, Chen HI, Chang SY, Yu D (2003) Correlation of CD44v5 expression with invasiveness and prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. J Formos Med Assoc 102: 229–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Sun Y, Ding JH, Lin S, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD, Li X (2007) Splicing regulator SC35 is essential for genomic stability and cell proliferation during mammalian organogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 27: 5393–5402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G, Fukabori Y, McBride G, Nikolaropolous S, McKeehan WL (1993) Exon switching and activation of stromal and embryonic fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-FGF receptor genes in prostate epithelial cells accompany stromal independence and malignancy. Mol Cell Biol 13: 4513–4522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbe LK, Pino I, Pio R, Cosper PF, Dwyer-Nield LD, Meyer AM, Port JD, Montuenga LM, Malkinson AM (2004) Relative amounts of antagonistic splicing factors, hnRNP A1 and ASF/SF2, change during neoplastic lung growth: implications for pre-mRNA processing. Mol Carcinog 41: 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Mulshine JL, Unsworth EJ, Scott FM, Avis IM, Vos MD, Treston AM (1996) Purification and characterization of a protein that permits early detection of lung cancer. Identification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-A2/B1 as the antigen for monoclonal antibody 703D4. J Biol Chem 271: 10760–10766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]