Abstract

Many of the qualitative roles of growth factors involved in neovascularization have been delineated, but it is unclear yet from an engineering perspective how to use these factors as therapies. We propose that an approach that integrates quantitative spatiotemporal measurements of growth factor signaling using 3-D in vitro and in vivo models, mathematic modeling of factor tissue distribution, and new delivery technologies may provide an opportunity to engineer neovascularization on demand.

Keywords: Therapeutic neovascularization, Angiogenesis, Growth factor, Temporal and spatial, Quantitative, Delivery system

1. Introduction

The vascular system provides a number of critical functions, including the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to all parts of the body, transport of waste products of metabolism, and delivery of circulating soluble factors, and stem and progenitor cells. Oxygen and nutrients diffuse out from capillaries into the surrounding tissue and are rapidly consumed by cells, such that if the distance between the capillaries and cells exceeds a few hundred microns hypoxia will occur. These vascular functions require the formation of a new vasculature in the vast majority of tissue regeneration and tissue engineering processes [1,2]. In addition, if the blood stream is restricted or obstructed by, for example, atherosclerotic plaques, the inadequate blood flow may cause coronary and peripheral arterial diseases. A possible treatment for these diseases is therapeutic neovascularization [3–6].

The current approaches to rebuild networks of blood vessels largely exploit the biology underlying blood vessel formation as it naturally occurs in development, and in pathological conditions such as cancer. Vascularization is initiated during embryonic development, and the development of the cardiovascular system precedes the development of all other organs in the embryo due to its central importance [1]. Vascularization continues during postnatal growth, and in the adult during the menstrual cycle, inflammation and wound healing. It is generally believed that neovascularization includes three processes, namely vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and arteriogenesis [7]. Vasculogenesis is de novo vessel network formation in the embryo from angioblasts or endothelial progenitor cells that migrate, proliferate and differentiate to form endothelial cells, and subsequently organize into cord-like structures as the primary plexus [8]. This process has also been recently suggested to occur in adulthood, where circulating endothelial progenitor cells are recruited to ischemic sites [9,10]. Angiogenesis refers to the process of blood vessel sprouting from preexisting capillaries, and includes subsequent remodeling processes such as pruning, vessel enlargement, and intussusception (vessel splitting) to form stable vessel networks [2,11–14]. Arteriogenesis mainly denotes the enlargement of arterial vessels to adjust for lost flow in other vessels [11,15], and this term is also used at times to include the process of remodeling of existing capillaries to form arterioles [16].

All vascularization processes involve a series of interactions among cytokines, growth factors, various types of cells, and enzymes. The onset of vascularization begins with the binding of biological agents to the surface receptors of endothelial or endothelial progenitor cells, and a resulting cascade of agents act in the subsequent processes of vascularization. Numerous growth factors involved in vasculogenesis [8], angiogenesis [17], and arteriogenesis [18] have been identified and characterized, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), placenta growth factor (PIGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), Angiopoietin-1 and Angiopoietin-2, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Growth factors are often chosen as drug candidates for rebuilding networks of blood vessels for therapeutic angiogenesis [19] or for tissue engineering [20].

Despite extensive studies on the biology and delivery of growth factors involved in vessel formation, and promising results with VEGF and bFGF, perhaps the two most important and best characterized factors in vascularization, in pre-clinical [21] and small-scale clinical trials [22,23], recent large-scale double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials that utilized either intracoronary and intravenous infusion of VEGF protein (VIVA) [24], intramuscular injection of VEGF gene by adenovirus vectors (RAVE) [25], or intracoronary infusion of rFGF-2 protein (FIRST) [26] did not lead to significant therapeutic benefits yet. These failures suggested that either these are the wrong molecular targets to induce neovascularization, that they can only be effectively utilized if formulated and administered correctly, or that their presentation in the context of the overall cellular microenvironment may play a vital role in their utility. It may be necessary to present these factors in a way that mimics natural signaling events, including the concentration, spatial and temporal profiles, and their simultaneous or sequential presentation with other appropriate factors.

This review will highlight the important role of growth factor presentation in controlling the neovascularization process and neovessel function. In particular, the role of the factor concentration and spatiotemporal presentation is major foci, as they are likely as crucial as the particular factor chosen for the therapy. In addition, this review will also discuss several key elements that may be required to translate this information into a therapeutic strategy, including 3-D in vitro and in vivo models, mathematic modeling and delivery technologies. The importance of delivering growth factors in the form of proteins, plasmid DNA, or transplanted cells overexpressing the growth factors of choice will not be discussed in detail here, as they have been covered elsewhere [27–29]. Regardless of what form is used for delivery, the design criteria for their delivery will likely remain the same. Transplanting stem cells or progenitors cells to patients as a neovascularization therapy is beyond the scope of this review, yet the effects of presentation of growth factors on the recruitment of progenitors cells that may participate in neovascularization will be briefly discussed.

2. Need for quantitative spatiotemporal control

A careful examination of growth factor signaling in neovascularization suggests this process requires a quantitative spatiotemporal control. VEGF will be used as the model factor in this examination, as it has been found to be one of the most important growth factors in all stages of neovascularization [30]: VEGF participates in vasculogenesis in embryonic development [31], initiates the sprouting of existing blood vessels by its mitogenic and chemotactic effects [31], drives the processes of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis [32], and also facilitates the recruitment of circulating endothelial progenitor cells to participate in neovascularization [33,34]. VEGF is also important in maintaining the survival of blood vessels [35] and withdrawal of VEGF can cause vascular collapse and regression [36]. Therefore under ischemic conditions when the endogenous VEGF is not sufficient to drive or complete the neovascularization process, introduction of exogenous VEGF is desirable.

2.1. Concentration

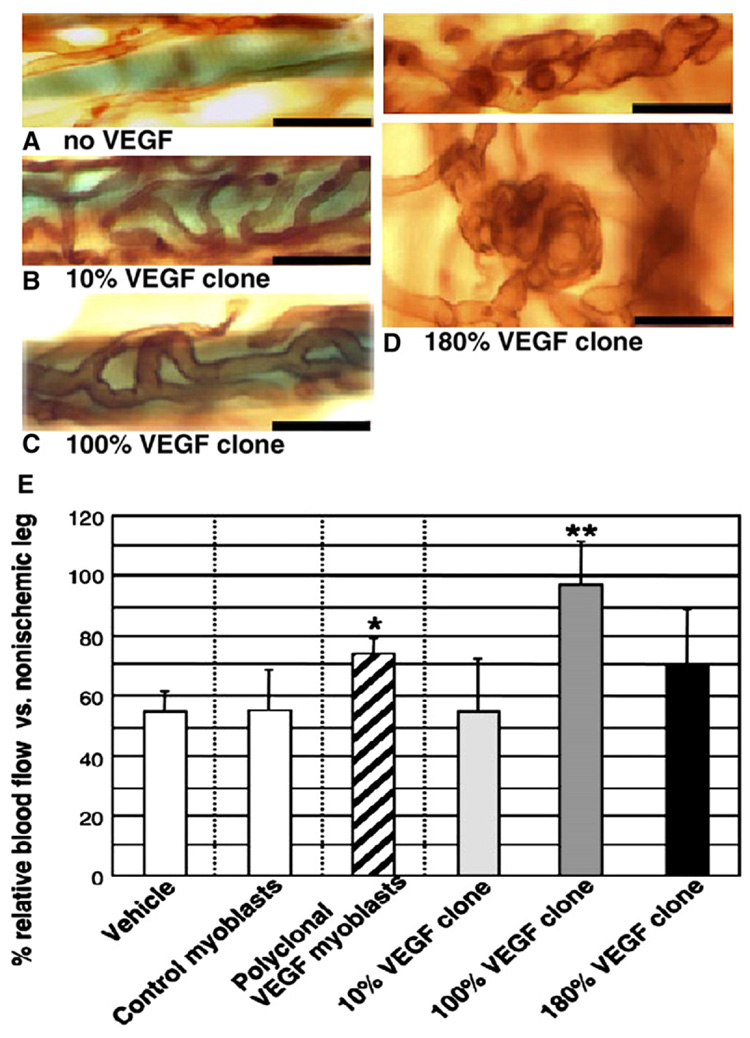

Several lines of evidence indicate that the concentration of VEGF must be strictly regulated to provide appropriate signaling to drive angiogenesis. The concentration of delivered exogenous growth factors ([v]) will affect the number of binding events that happen on the cell surface receptors, and the extent of subsequent downstream intracellular signaling that dictates the proliferation, migration and differentiation of endothelial and progenitor cells. It is expected that [v] needs to reach a threshold to generate adequate intracellular signaling. Insufficient VEGF expression leads to embryonic lethality [37,38]. On the other hand, excessive [v]may saturate the available receptors and downregulate receptor expression. For example, modest increases in VEGF gene expression can cause severe abnormalities in heart development and embryonic lethality [39], and excess VEGF can induce severe vascular leakage [40], hypertension [41], malformed and haemorrhagic vessels [42], abnormal vascular trees and disruptive edema [43] and cardiovascular malformation [44]. In contrast, an optimal level of VEGF expression may be required to completely restore blood flow and collateral growth [45] (Fig. 1). The VEGF concentration has also been found to be important in other biological processes (e.g., neuroprotective effects in dopaminergic neurons [46] and ischemic brain tissue [47]). The concept of dose thresholds is also reflected in other angiogenic growth factors; for example, overexpression of bFGF can cause tumor formation [48]. Altogether, the existing data indicate that [v] is a key parameter to consider in the delivery of exogenous growth factors.

Fig. 1.

The impact of the local concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) on new blood vessel size (A–D) and blood flow in the ischemia region (E). Transgenic mice myoblasts expressing VEGF were implanted into mice ear muscle (A–D) and mice hindlimb muscle (E) subject to femoral artery ligation. Three monoclonal populations secreted 10%, 100% and 180% of the average VEGF levels of the parental polyclonal population per cell in vitro. Vessel size increased with the increase of VEGF concentration (A–C), but the 180% VEGF clone led to enlarged and glomeruloid bodies (D). The optimal concentration of VEGF (100% clone) induced larger blood flow than either higher (180% clone) or lower (10% clone) VEGF concentrations (E). (Ref. [45], with permission from the FASEB Journal).

2.2. Temporal gradient

The temporal gradient of a growth factor (d[v]/dt) is another important variable in neovascularization processes. The half-life of exogenous VEGF is around 50 min in vivo [49], and as the survival of endothelial cells is dependent on VEGF in the early stages of angiogenesis, endothelial cells will undergo apoptosis and new blood vessels will regress with too short of VEGF exposure [36,50,51]. In contrast, the extended presence of growth factors within a local environment can lead to abnormal vessel growth and immune dysfunction [52,53], suggesting the time window in which growth factors can have a beneficial effect may be restricted. For example, bolus injection of VEGF daily for 28 days improved collateral flow while 7 days of injection did not [49]. MCP-1 facilitated arteriogenesis following artery ligation only in the first week, while introduction of MCP-1 after 3 weeks led to no significant difference against controls [54]. In contrast, the absence of MCP-1 in a mice artery occlusion model caused reduced blood flow restoration [55]. Similarly, induction of Angiopoietin-2 in mice with ischemic retinopathy during the ischemic period resulted in a significant increase in neovascularization in the retina, but induction of Angiopoietin-2 at a later time point enhanced regression of neovessels [56].

One must also consider that all vessel formation results from a multi-step sequential cascade in which multiple factors come into play at different time points. For example, angiogenesis starts with the activation and migration of endothelial cells into the surrounding matrix, and the formation of an immature and unstable vessel network [11]. After a series of remodeling and pruning processes, a stable and mature vessel network is formed by the recruitment of smooth muscle cells and pericytes [17,57]. During this process, VEGF and Angiopoietin-2 act in concert to destabilize preexisting blood vessels, to induce degradation of basement membrane, and to promote the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells [17]. Other factors such as Angiopoietin-1 and PDGF-BB act at later stages to stabilize the newly formed vessels [17,57]. Co-existence of destabilizing and stabilizing factors may cancel each other’s effects, thus the temporal profiles or kinetics of presentation of different growth factors should be taken into account to recapitulate the natural hierarchical formation of normal vascular networks.

2.3. Spatial gradient

The spatial gradient of angiogenic factors (d[v]/dr) may also dictate the architecture and functionality of new vessel networks. The directionality of angiogenesis as reflected by the directional migration of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, and the branching morphogenesis, are highly regulated by the spatial gradient of VEGF [58–61]. It is also critical to control d[v]/dr to avoid undesirable side-effects at distant sites due to high [v] at those locations, including unwanted vessel growth (e.g., diabetic retinopathy) [62], or increasing dormant tumor vasculature growth [63]. Spatial gradients are created naturally due to the diffusive nature of their transport through tissues, and their simultaneous degradation. In addition, the different isoforms of VEGF-A, all of which are important in vessel development, are distinguished by their differential binding affinity to the extracellular matrix [40]. VEGF 120 (121 for human) is fully diffusible as it has no binding capability to the extracellular matrix, and can potentially signal to endothelial cells at relatively long distances. However, transgenic mice expressing only VEGF120 developed tortuous and dilated myocardial capillaries, reduced branching and increased capillary diameter, even though the total VEGF levels were the same as wild-type animals [64,65]. In contrast, VEGF 188 (189 for human) has the most binding capability, and does not diffuse through tissues. Yet VEGF188 mice showed ectopic branching and reduced capillary diameter [65]. The differential binding affinity of VEGF isoforms may allow the formation of spatial gradients and concentrations in distinct locations of a vessel. The tips of endothelial cell sprouts have been suggested to respond to the spatial gradient of VEGF, while stalk cells may proliferate in response to the local VEGF concentration [66]. The VEGF spatial gradient may thus regulate the balance between the migration of tip cells and the proliferation of stalk cells to control the vascular pattern [61]. The breakdown of this balance may be responsible for abnormal vascular patterns under pathological situations [61]. Similar spatial effects have also been shown in PDGF-BB mutant mice, in which the deletion of a motif in the PDGF-BB gene responsible for the association with cell surface caused a 50% reduction in pericyte recruitment, and abnormal pericyte morphology [67].

Another potentially important spatial aspect of growth factor signaling in neovascularization is the tissue- and anatomy site-dependency as VEGF isoforms have differential expression in different tissues [68,69]. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis also appear to differ for the vascular beds in different tissues [70]. Neovascularization in skin suffering from psoriasis resulted in enlarged vessels [71] whereas in retina angiogenesis led to capillary sprouting [72]. The contributions of different growth factors in different anatomic sites may also vary. For example, in muscle of hindlimbs subjected to femoral artery ligation, angiogenesis is the dominant neovascularization process [73] and this requires high concentrations of angiogenic factors such as VEGF and Angiopoietin-2 to induce sprouting from pre-existing capillaries. In contrast, near the ligation site arteriogenesis or collateral vessel growth may be the major processes, and arteriogenic factors such as MCP-1 and GM-CSF likely take a leading role in remodeling arterioles to restore blood flow [18,74–76].

2.4. Further considerations

Growth factor signaling in neovascularization involves precise regulation of the concentration, temporal gradient, and spatial gradient of factors, and these key parameters will likely control the final outcome of neovascularization therapies. However, data generated to date are mainly based on experimental models utilizing young and healthy animals. It is expected that the concentrations, and spatial and temporal gradients need to be reevaluated and customized for human subjects. Moreover, aged or diseased patients may have distinct capabilities for neovascularization. For example, diabetic patients have reduced angiogenic responsiveness [77,78] as do aged subjects [79]. This could result from impaired growth factor/receptor signaling [80], a reduction in endothelial cell responsiveness, or a reduction of the number of circulating progenitor cells [81,82]. Even for a population with similar health, subtle variations may still arise due to individual genetic differences [83].

3. Designing delivery systems

The biology of neovascularization points to the need for a quantitative spatiotemporal control over growth factor signaling. This leads to two important questions. First, can one establish specific quantitative design criteria for the exposure of tissues to growth factors to drive neovascularization? Second, how can one develop proper delivery systems to achieve these design criteria?

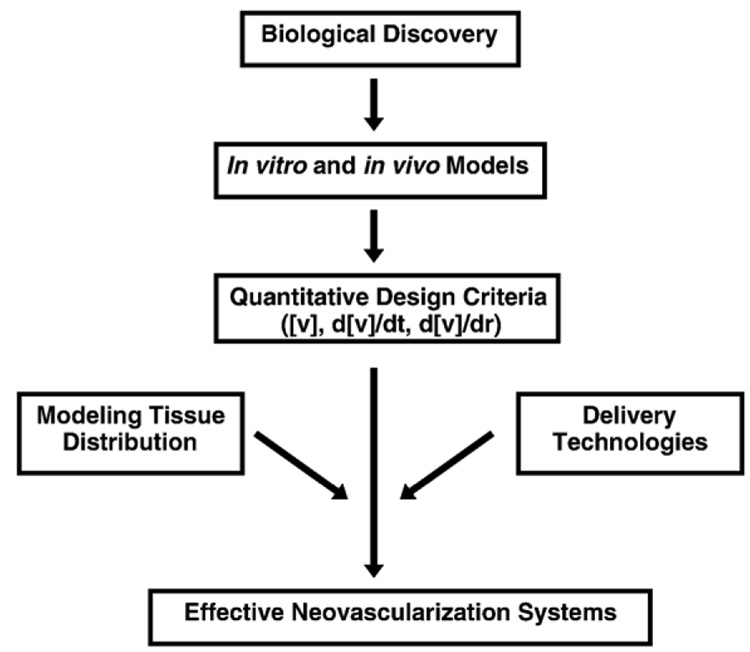

We propose that an approach that integrates appropriate in vitro and in vivo experimental models to delineate the design criteria, mathematical modeling of factor distribution, and delivery technologies, can translate the design criteria to effective therapies and provide an opportunity to engineer neovascularization on demand (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the proposed integrated approach to develop effective neovascularization strategies. Quantitative design criteria are the core to developing effective neovascularization therapies and these criteria are based on biological discovery and appropriate in vitro and in vivo models. The translation of the design criteria into effective systems requires integration with mathematical modeling of growth factor tissue distribution and delivery technologies to achieve appropriate spatiotemporal introduction of factors into the site of interest.

3.1. Quantitative in vitro and in vivo models

Appropriate in vitro or in vivo models allowing quantitative characterization of the effects of growth factors in neovascularization are crucial for the development of design criteria for therapies. In vivo models, such as the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay, corneal assay, dorsal skin chamber assay, subcutaneous implant and induced ischemia models [84–87], mimic certain aspects of human diseases. However it is challenging to extract and validate a complete list of design parameters from a single model. In addition, the complexity of the biology in in vivo models, (e.g., the presence of endogenous growth factors secreted by multiple types of cells), makes it difficult to distinguish the quantitative contribution of individual factors. Furthermore, the time and effort required with in vivo models hinder rapid and large-scale quantitative screenings for factors of interest.

3-D in vitro models capture some complex features of the in vivo cellular environment [88], but still allow quantitative assessment of the roles of growth factors in neovascularization. In vitro sprouting assays using endothelial cells embedded in a natural extracellular matrix (ECM) such as fibrin [89–91], collagen [92], or Matrigel [93] can mimic multiple angiogenesis events (proliferation, migration, differentiation, and tubule formation) in a natural sequence, and can be used to evaluate the effect of added growth factors in a temporally and spatially controlled manner. However, certain limitations of the in vitro models still exist. The ECM may degrade before the neovascularization process is completed, and the assays do not typically include other cell types needed for remodeling. Co-culture of endothelial cells with other cell types such as smooth muscle cells, may affect the gene expression of angiogenic factors [94] and VEGF responsiveness [95]. In addition, the choice of endothelial cell type and animal species or strain may alter the findings. Endothelial cells from divergent human vessel origins exhibited significantly different responsiveness to the same growth factor stimuli [96]. Transgenic animals (e.g., apolipo-protein E knock-out mice) may provide particularly relevant cells to study neovascularization in vitro in the context of specific diseases (e.g., atherosclerosis) [97]. These issues need to be addressed for choosing appropriate in vitro models.

Imaging techniques are likely another key to the delineation of neovascularization design criteria [98,99]. The final outcome of interventions needs to be assessed by a number of parameters including blood vessel density, vessel size, extent of vessel maturation, and blood perfusion rate, all of which require accurate and correct characterization. Imaging techniques that work at different molecular, cellular and tissue levels may all be useful. For example, biodistribution of VEGF can be visualized by staining [100] or by radiolabeling [101]. The dynamic nature of a series of angiogenesis events can be monitored by in situ time-lapse imaging [102]. Lumen formation, blood vessel density and size, and vessel maturation, can be examined in tissue sections [103]. The architecture and pattern of new blood vessel networks can be assessed by X-ray computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [99]. The endpoint of neovascularization, restoration of blood flow, can be visualized by ultrasound, near-infrared optical imaging, laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDPI), or fluorescent microsphere perfusion [99,104,105]. The validity of design criteria for neovascularization therapies will heavily rely on the accuracy of the analysis used in their establishment.

3.2. Mathematic modeling of factor distribution

It will be critical to understand and predict growth factor distribution in vivo if one is to design systems that achieve a desirable tissue exposure to these factors, and mathematic models can potentially provide this information [106–108]. Moreover, modeling may be crucial to allow scale-up, as one takes data obtained on mice or other small animals models and attempts to extrapolate to human subjects. The concentration and gradients of endogenous and exogenous factors in time and space within tissues of interest in vivo are controlled by a few parameters: the rate at which factors are introduced into the tissue (production rate), the rates of diffusion and convection in the extracellular microenvironment (transport rate), and the consumption rate of factors by cellular endocytosis and degradation. The production rate of exogenous angiogenic factors such as VEGF can be readily controlled (discussed in Delivery technologies section), and endogenous VEGF secretion induced by hypoxia can be correlated with the oxygen distribution using finite element analysis [109]. The transport of delivered growth factors through the delivery systems, including polymer scaffolds, microspheres, or transplanted cells, has been modeled previously [107]. Assuming the effect of convection within tissues is negligible, the diffusivity of growth factors can be calculated based on known experimental parameters [108,110]. The half-lives of growth factors are also readily measured, and the binding kinetics of angiogenic factors to cell surface receptors can be modeled by taking into consideration the effect of VEGF receptors expression and the cellular internationalize rate of VEGF [111,112]. Altogether, these parameters can be used to predict the distribution of growth factors within tissues of interest [108,113] for the assessment of design criteria for delivery systems. However, it is still challenging to validate these models with experimental methods due to the complexity of these systems [114]. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of other proteins [115,116] may be useful to provide information to guide studies on neovascularization factor tissue distribution.

3.3. Delivery technologies

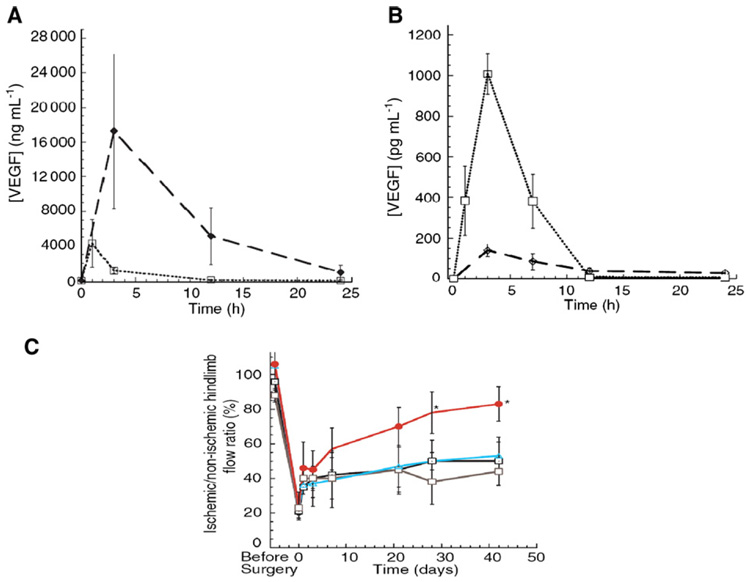

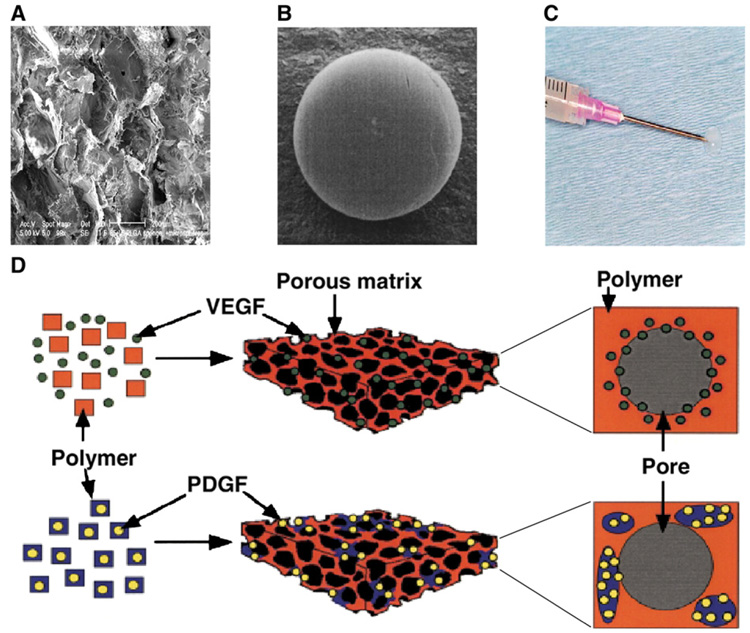

Quantitative studies of neovascularization processes and mathematical modeling of factor distribution are anticipated to provide specific criteria for factor introduction into tissues that must be met with delivery technologies. Unfortunately, the most commonly used delivery strategies for neovascularization therapies utilize bolus injection or infusion into systemic circulation or the tissues of interest. The rapid degradation of these proteins and the resultant low local availability (Fig. 3) do notmeet the spatial and temporal design criteria, and it is probably not surprising that large-scale clinical trails have not been successful [24,117,118]. In contrast, polymer vehicles encapsulating growth factors can provide a controlled release into the local cellular microenvironment to yield desirable concentrations over a period of days to months (Fig. 3). Moreover, polymer properties can be readily manipulated to change the temporal and spatial release profiles, making polymer delivery systems promising candidates for neovascularization therapies [119–123]. The most commonly used polymers for angiogenic factor delivery include synthetic polymers such as poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), and their copolymers (PLGA) [124–126], and natural polymers such as fibrin [127], collagen [128], alginate [129–131], chitosan [132], gelatin [133] and other hydrogels [134,135]. Delivery vehicles have been made in the physical forms of porous scaffolds, hydrogels, or microspheres to deliver VEGF according to specific applications [20,121,123] (Fig. 4). The fabrication method used to produce the scaffold or vehicle can denature or inactivate the incorporated angiogenic factors, which places an emphasis on this aspect of this technology. For example, the gas-foaming techniques can be used to produce porous materials that retain the bioactivity of incorporated and released VEGF [136].

Fig. 3.

Examples of the effects of in vivo temporal and spatial presentation of exogenous vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) on restoring blood perfusion in ischemia. A) VEGF delivered by injectable alginate hydrogels (♦) led to a higher concentration in the local injection region than VEGF delivered by bolus injection (□). B) In contrast, VEGF delivered by injectable alginate hydrogels (♦) exhibited a lower concentration in the systemic circulation (peripheral serum) than VEGF delivered by bolus injection (□). C) Local presentation of VEGF delivered from alginate gels (●) induced higher blood perfusion in the ischemia region than VEGF delivered with bolus injection ( ), alginate vehicle alone (△), or blank control condition (□). (Ref. [130], with permission from Blackwell Publishing).

), alginate vehicle alone (△), or blank control condition (□). (Ref. [130], with permission from Blackwell Publishing).

Fig. 4.

Examples of delivery systems for neovascularization factors. A) Scanning electron micrograph of a typical poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) scaffold. B) PLGA microspheres. C) Injectable alginate hydrogel. D) Combination of scaffolds and microspheres. Scaffold can incorporate VEGF only or be fabricated from PDGF pre-encapsulated PLGA microspheres. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [Nature Biotechnology], (Ref. [103]), copyright (2001).

The local concentration of neovascularization factors delivered with polymer carriers can be altered by adjusting the physical or chemical properties of the vehicles. Porosity, pore size, inter-pore distance, tortuosity, the degree of crosslinking, and the degradation rate all affect the diffusion of encapsulated proteins through the polymer network. Pore size and porosity have also been found to affect host inflammation and angiogenesis [137–139]. Varying the composition of synthetic polymer such as PLGA can control the degradation rate to produce differential VEGF release profiles [140]. Natural polymer like alginate can be oxidized, irradiated, crosslinked or varied in the molecular weight distribution [141–143] to affect the degradation rate. Reversible binding of the factors to the alginate vehicles is also often used to modulate the factor release rate [144]. In addition to passive diffusion, systems can be designed to release angiogenic growth factors in response to specific cues from the cellular environment, including cell secreted proteinases [145,146] and mechanical signals [131]. Polymer systems can also be customized to allow sequential growth factor delivery [147] (Fig. 4), and sequential release of VEGF and PDGF-BB [103], VEGF and Angiopoietin-1 [148], or FGF-2 and PDGF-BB [149] have proved to induce more mature and stable vessel networks than introducing the factors simultaneously.

Spatial gradients of factors in tissues can be controlled by varying the placement of polymer vehicles, immobilizing insoluble ligands on polymer networks to localize cells of interest, or designing delivery systems to provide spatially distinct cues. For example, a porous bi-layered PLG scaffold system locally presenting VEGF alone in one spatial region, and VEGF and PDGF-BB in an adjacent region produced spatially different vessel morphologies [150]. Similarly, presenting pro- and anti-angiogenesis factors at different locations in the polymer scaffold may produce distinct vascular structures. Patterning endothelial cells or mural cells by coupling cell adhesive ligands such as Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) [151,152] to the location of interest can also be used to control the neovessel region, and the nano-scale organization of RGD may affect endothelial cell adhesion and motility [153,154]. Modern 3-D fabrication techniques provide more opportunities to control the geometry and patterning of polymer scaffolds [155], thus making it possible to integrate growth factor releasing vehicles into micro- or nano-scale electromechanical devices [156–158] to have more accurate control over spatial and temporal presentation of factors. The combination of growth factor delivery-based neovascularization therapies with nanomedicine strategies [159] may also offer more exciting research and practical applications.

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

Quantitative spatiotemporal information concerning the impact of angiogenic or arteriogenic factors on cell populations of interest is critical for understanding the basic biology of neovascularization, and for rational design of therapeutic growth factor delivery systems. Continual progress in understanding the basic biology of neovascularization in development, physiologic and pathologic conditions will provide important information for the design of these systems. The advancement of appropriate 3-D in vitro or in vivo models, including accurate characterization methods (e.g., in situ imaging techniques), will facilitate these studies. Of special note, while limited quantitative data currently exists for the early stages of angiogenesis, understanding and controlling the vessel remodeling processes in angiogenesis and arteriogenesis may lead to important new opportunities. In this regard, quantitative criteria are desired for vessel maturation factors such as PDGF-BB and Angiopoietin-2 that mediate the association of the mural cells to newly formed vessels, and pro-arteriogenesis factors such as MCP-1 and GM-CSF that affect the enlargement of collateral vessels. In addition, the effects of controlled presentation of angiogenic factors on homing of circulating progenitor and stem cells are also not well understood currently in a quantitative manner. The establishment of predictive mathematical models of factor tissue distribution, in concert with the development of novel and potent delivery technologies, will also dramatically improve neovascularization therapies.

Growth factor induced neovascularization processes are multivariate events. Because of the highly interlinked relationship between growth factors, multiple types of cells, extracellular matrix, delivery vehicles, hydrodynamic forces, and interstitial flow, ultimately a system biology approach incorporating all of these factors may be needed to fully appreciate the complex nature of these processes and generate optimal therapies.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Institute of Health to their laboratory (RO1 HL 069957).

Footnotes

This review is part of the Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews theme issue on “Natural and Artificial Cellular Microenvironments for Soft Tissue Repair”.

References

- 1.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Diagnostic and therapeutic applications of angiogenesis research. C. R. Acad. Sci., Ser. III. 1993;316:909–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isner JM. Therapeutic angiogenesis: a new frontier for vascular therapy. Vasc. Med. 1996;1:79–87. doi: 10.1177/1358863X9600100114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes GC, Annex BH. Angiogenic therapy for coronary artery and peripheral arterial disease. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2005;3:521–535. doi: 10.1586/14779072.3.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao YH, Hong A, Schulten H, Post MJ. Update on therapeutic neovascularization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005;65:639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Muinck ED, Simons M. Re-evaluating therapeutic neovascularization. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patan S. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cancer Treat. Res. 2004;117:3–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8871-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, Chen D, Silver M, Kearney M, Magner M, Isner JM, Asahara T. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nat. Med. 1999;5:434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li B, Sharpe EE, Maupin AB, Teleron AA, Pyle AL, Carmeliet P, Young PP. VEGF and PlGF promote adult vasculogenesis by enhancing EPC recruitment and vessel formation at the site of tumor neovascularization. FASEB J. 2006;20:E664–E676. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5137fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat. Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dvorak HF. Angiogenesis: update 2005. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:1835–1842. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer ML. Abalancing act: therapeutic approaches for the modulation of angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2006;7:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons M. Angiogenesis: where do we stand now? Circulation. 2005;111:1556–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159345.00591.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helisch A, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis: the development and growth of collateral arteries. Microcirculation. 2003;10:83–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price RJ, Owens GK, Skalak TC. Immunohistochemical identification of arteriolar development using markers of smooth muscle differentiation. Evidence that capillary arterialization proceeds from terminal arterioles. Circ. Res. 1994;75:520–527. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat. Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaper W, Scholz D. Factors regulating arteriogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:1143–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000069625.11230.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losordo DW, Dimmeler S. Therapeutic angiogenesis and vasculogenesis for ischemic disease. Part I: angiogenic cytokines. Circulation. 2004;109:2487–2491. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128595.79378.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen RR, Mooney DJ. Polymeric growth factor delivery strategies for tissue engineering. Pharm. Res. 2003;20:1103–1112. doi: 10.1023/a:1025034925152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeshita S, Zheng LP, Brogi E, Kearney M, Pu LQ, Bunting S, Ferrara N, F. SJ, Isner JM. Therapeutic angiogenesis. A single intraarterial bolus of vascular endothelial growth factor augments revascularization in a rabbit ischemic hind limb mode. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:662–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI117018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Udelson JE, Dilsizian V, Laham RJ, Chronos N, Vansant J, Blais M, Galt JR, Pike M, Yoshizawa C, Simons M. Therapeutic angiogenesis with recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2 improves stress and rest myocardial perfusion abnormalities in patients with severe symptomatic chronic coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102:1605–1610. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumacher B, Pecher P, von Specht BU, Stegmann T. Induction of neoangiogenesis in ischemic myocardium by human growth factors: first clinical results of a new treatment of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1998;97:645–650. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry TD, Annex BH, McKendall GR, Azrin MA, Lopez JJ, Giordano FJ, Shah PK, Willerson JT, Benza RL, Berman DS, Gibson CM, Bajamonde A, Rundle AC, Fine J, McCluskey ER. VIVA Investigators, The VIVA trial: vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemia for vascular angiogenesis. Circulation. 2003;107:1359–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061911.47710.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajagopalan S, Mohler ER, Lederman RJ, Mendelsohn FO, Saucedo JF, Goldman CK, Blebea J, Macko J, Kessler PD, Rasmussen HS, Annex BH. Regional angiogenesis with vascular endothelial growth factor in peripheral arterial disease: a phase II randomized, double-blind, controlled study of adenoviral delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor 121 in patients with disabling intermittent claudication. Circulation. 2003;108:1933–1938. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093398.16124.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simons M, Annex BH, Laham RJ, Kleiman N, Henry T, Dauerman H, Udelson JE, Gervino EV, Pike M, Whitehouse MJ, Moon T, Chronos NA. Pharmacological treatment of coronary artery disease with recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2: double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Circulation. 2002;105:788–793. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Tissue engineering strategies for in vivo neovascularisation. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2002;2:805–818. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storrie H, Mooney DJ. Sustained delivery of plasmid DNA from polymeric scaffolds for tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:500–514. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafii S, Lyden D. Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nat. Med. 2003;9:702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr. Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K, Rossant J. Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature. 2005;438:937–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruhrberg C. Growing and shaping the vascular tree: multiple roles for VEGF. BioEssays. 2003;25:1052–1060. doi: 10.1002/bies.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asahara T, Takahashi T, Masuda H, Kalka C, Chen DH, Iwaguro H, Inai Y, Silver M, Isner JM. VEGF contributes to postnatal neovascularization by mobilizing bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:3964–3972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunewald M, Avraham I, Dor Y, Bachar-Lustig E, Itin A, Jung S, Chimenti S, Landsman L, Abramovitch R, Keshet E. VEGF-induced adult neovascularization: recruitment, retention, and role of accessory cells. Cell. 2006;124:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alon T, Hemo I, Itin A, Pe’er J, Stone J, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat. Med. 1995;1:1024–1028. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamin LE, K E. Conditional switching of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in tumors: induction of endothelial cell shedding and regression of hemangioblastoma-like vessels by VEGF withdrawal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:8761–8766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, Declercq C, Pawling J, Moons L, Collen D, Risau W, Nagy A. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miquerol L, Langille BL, Nagy A. Embryonic development is disrupted by modest increases in vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. Development. 2000;127:3941–3946. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrara N, Gerber H-P, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiefer FN, Neysari S, Humar R, Li W, Munk VC, Battegay EJ. Hypertension and angiogenesis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003;9:1733–1744. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drake CJ, Little CD. Exogenous vascular endothelial growth-factor induces malformed and hyperfused vessels during embryonic neovascularization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:7657–7661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dor Y, Djonov V, Abramovitch R, Itin A, Fishman GI, Carmeliet P, Goelman G, Keshet E. Conditional switching of VEGF provides new insights into adult neovascularization and pro-angiogenic therapy. EMBO J. 2002;21:1939–1947. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feucht M, Christ B, Wilting J. VEGF induces cardiovascular malformation and embryonic lethality. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;151:1407–1416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Degenfeld G, Banfi A, Springer ML, Wagner RA, Jacobi J, Ozawa CR, Merchant MJ, Cooke JP, Blau HM. Microenvironmental VEGF distribution is critical for stable and functional vessel growth in ischemia. FASEB J. 2006;20:E2277–E2287. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6568fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasuhara T, Shingo T, Muraoka K, Ji YW, Kameda M, Takeuchi A, Yano A, Nishio S, Matsui T, Miyoshi Y, Hamada H, Date I. The differences between high and low-dose administration of VEGF to dopaminergic neurons of in vitro and in vivo Parkinson’s disease model. Brain Res. 2005;1038:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manoonkitiwongsa PS, Schultz RL, McCreery DB, Whitter EF, Lyden PD. Neuroprotection of ischemic brain by vascular endothelial growth factor is critically dependent on proper dosage and may be compromised by angiogenesis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:693–702. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000126236.54306.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sola F, Gualandris A, Belleri M, Giuliani R, Coltrini D, Bastaki M, Tosatti MP, Bonardi F, Vecchi A, Fioretti F, Ciomei M, Grandi M, Mantovani A, Presta M. Endothelial cells overexpressing basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) induce vascular tumors in immunodeficient mice. Angiogenesis. 1997;1:102–116. doi: 10.1023/A:1018309200629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazarous DF, Shou M, Scheinowitz M, Hodge E, Thirumurti V, Kitsiou AN, Stiber JA, Lobo AD, Hunsberger S, Guetta E, Epstein SE, Unger EF. Comparative effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor on coronary collateral development and the arterial response to injury. Circulation. 1996;94:1074–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell CA, Risau W, Drexler HC. Regression of vessels in the tunica vasculosa lentis is initiated by coordinated endothelial apoptosis: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor as a survival factor for endothelium. Dev. Dyn. 1998;213:322–333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199811)213:3<322::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meeson AP, Argilla M, Ko K, Witte L, Lang RA. VEGF deprivation-induced apoptosis is a component of programmed capillary regression. Development. 1999;126:1407–1415. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 1996;2:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laxmanan S, Robertson SW, Wang E, Lau JS, Briscoe DM, Mukhopadhyay D. Vascular endothelial growth factor impairs the functional ability of dendritic cells through Id pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoefer IE, van Royen N, Buschmann IR, Piek JJ, Schaper W. Time course of arteriogenesis following femoral artery occlusion in the rabbit. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;49:609–617. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voskuil M, Hoefer IE, van Royen N, Hua J, de Graaf S, Bode C, Buschmann IR, Piek JJ. Abnormal monocyte recruitment and collateral artery formation in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 deficient mice. Vasc. Med. 2004;9:287–292. doi: 10.1191/1358863x04vm571oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oshima Y, Oshima S, Nambu H, Kachi S, Takahashi K, Umeda N, Shen J, Dong A, Apte RS, Duh E, Hackett SF, Okoye G, Ishibashi K, Handa J, Melia M, Wiegand S, Yancopoulos G, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA. Different effects of angiopoietin-2 in different vascular beds: new vessels are most sensitive. FASEB J. 2005;19:963–965. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2209fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peirce SM, Skalak TC. Microvascular remodeling: a complex continuum spanning angiogenesis to arteriogenesis. Microcirculation. 2003;10:99–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tufro A. VEGF spatially directs angiogenesis during metanephric development in vitro. Dev. Biol. 2000;227:558–566. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grosskreutz CL A-AB, Duplaa C, Quinn TP, Terman BI, Zetter B, D’Amore PA. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Microvasc. Res. 1999;58:128–136. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Makanya AN, Stauffer D, Ribatti D, Burri PH, Djonov V. Micro-vascular growth, development, and remodeling in the embryonic avian kidney: the interplay between sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenic mechanisms. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2005;66:275–288. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C. How do endothelial cells orientate? EXS. 2005;94:3–15. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7311-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gariano RF, Gardner TW. Retinal angiogenesis in development and disease. Nature. 2005;438:960–966. doi: 10.1038/nature04482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Indraccolo S, Stievano L, Minuzzo S, Tosello V, Esposito G, Piovan E, Zamarchi R, Chieco-Bianchi L, Amadori A. Interruption of tumor dormancy by a transient angiogenic burst within the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:4216–4221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carmeliet P, Ng YS, Nuyens D, Theilmeier G, Brusselmans K, Cornelissen I, Ehler E, Kakkar VV, Stalmans I, Mattot V, Perriard JC, Dewerchin M, Flameng W, Nagy A, Lupu F, Moons L, Collen D, D’Amore PA, Shima DT. Impaired myocardial angiogenesis and ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Nat. Med. 1999;5:491–492. doi: 10.1038/8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruhrberg C, Gerhardt H, Golding M, Watson R, Ioannidou S, Fujisawa H, Betsholtz C, Shima DT. Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2684–2698. doi: 10.1101/gad.242002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D, Betsholtz C. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lindblom P, Gerhardt H, Liebner S, Abramsson A, Enge M, Hellstrom M, Backstrom G, Fredriksson S, Landegren U, Nystrom HC, Bergstrom G, Dejana E, Ostman A, Lindahl P, Betsholtz C. Endothelial PDGF-B retention is required for proper investment of pericytes in the microvessel wall. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1835–1840. doi: 10.1101/gad.266803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bacic M, Edwards NA, Merrill MJ. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (vascular permeability factor) forms in rat tissues. Growth Factors. 1995;12:11–15. doi: 10.3109/08977199509003209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ng YS, Rohan R, Sunday ME, Demello DE, D’Amore PA. Differential expression of VEGF isoforms in mouse during development and in the adult. Dev. Dyn. 2001;220(2):112–121. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1093>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pettersson A, Nagy JA, Brown LF, Sundberg C, Morgan E, Jungles S, Carter R, Krieger JE, Manseau EJ, Harvey VS, Eckelhoefer IA, Feng D, Dvorak AM, Mulligan RC, Dvorak HF. Heterogeneity of the angiogenic response induced in different normal adult tissues by vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Lab. Invest. 2000;80:99–115. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leong TT, Fearon U, Veale DJ. Angiogenesis in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: clues to disease pathogenesis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2005;7:325–329. doi: 10.1007/s11926-005-0044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kvanta A. Ocular angiogenesis: the role of growth factors. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006;84:282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ito WD, Arras M, Scholz D, Winkler B, Htun P, Schaper W. Angiogenesis but not collateral growth is associated with ischemia after femoral artery occlusion. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 1997;273:H1255–H1265. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buschmann IR, Hoefer IE, van Royen N, Katzer E, Braun-Dulleaus R, Heil M, Kostin S, Bode C, Schaper W. GM-CSF: a strong arteriogenic factor acting by amplification of monocyte function. Atherosclerosis. 2001;159:343–356. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hershey JC, Baskin EP, Glass JD, Hartman HA, Gilberto DB, Rogers IT, Cook JJ. Revascularization in the rabbit hindlimb: dissociation between capillary sprouting and arteriogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;49:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Voskuil VRNM, Hoefer IE, Seidler R, Guth BD, Bode C, Schaper W, Piek JJ, Buschmann IR. Modulation of collateral artery growth in a porcine hindlimb ligation model using MCP-1. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H1422–H1428. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00506.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martin A, Komada MR, Sane DC. Abnormal angiogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Med. Res. Rev. 2003;23:117–145. doi: 10.1002/med.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waltenberger J, Lange J, Kranz A. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A-induced chemotaxis of monocytes is attenuated in patients with diabetes mellitus — a potential predictor for the individual capacity to develop collaterals. Circulation. 2000;102:185–190. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martinez P, Esbrit P, Rodrigo A, Alvarez-Arroyo MV, Martinez ME. Age-related changes in parathyroid hormone-related protein and vascular endothelial growth factor in human osteoblastic cells. Osteoporos. Int. 2002;13:874–881. doi: 10.1007/s001980200120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Waltenberger J. Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;49:554–560. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eizawa T, Murakami Y, Matsui K, Takahashi M, Muroi K, Amemiya M, Takano R, Kusano E, Shimada K, Ikeda U. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells are reduced in hemodialysis patients. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2003;19:627–633. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheubel RJ, Zorn H, Silber RE, Kuss O, Morawietz H, Holtz J, A S. Age-dependent depression in circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rakic JM, Lambert V, Munaut C, Bajou K, Peyrollier K, Alvarez-Gonzalez ML, Carmeliet P, Foidart JM, Noel A. Mice without uPA, tPA, or plasminogen genes are resistant to experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:1732–1739. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jain RK, Schlenger K, Hockel M, Yuan F. Quantitative angiogenesis assays: progress and problems. Nat. Med. 1997;3:1203–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Auerbach R, Lewis R, Shinners B, Kubai L, Akhtar N. Angiogenesis assays: a critical overview. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:32–40. doi: 10.1373/49.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Staton CA, Stribbling SM, Tazzyman S, Hughes R, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. Current methods for assaying angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2004;85:233–248. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hasan J, Shnyder SD, Bibby M, Double JA, Bicknel R, Jayson GC. Quantitative angiogenesis assays in vivo—a review. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:1–16. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000037338.51851.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat. Rev., Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakatsu MN, Sainson RCA, Aoto JN, Taylor KL, Aitkenhead M, Perez-del-Pulgar S, Carpenter PM, Hughes CCW. Angiogenic sprouting and capillary lumen formation modeled by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in fibrin gels: the role of fibroblasts and Angiopoietin-1. Microvasc. Res. 2003;66:102–112. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(03)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakatsu MN, Sainson RCA, Pérez-del-Pulgar S, Aoto JN, Aitkenhead M, Taylor KL, Carpenter PM, Hughes CCW. VEGF121 and VEGF165 regulate blood vessel diameter through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in an in vitro angiogenesis model. Lab. Invest. 2003;83:1873–1885. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000107160.81875.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nehls V, Drenckhahn D. A novel, microcarrier-based in vitro assay for rapid and reliable quantification of three-dimensional cell migration and angiogenesis. Microvasc. Res. 1995;50:311–322. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1995.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dietrich F, Lelkes PI. Fine-tuning of a three-dimensional microcarrier-based angiogenesis assay for the analysis of endothelial–mesenchymal cell co-cultures in fibrin and collagen gels. Angiogenesis. 2006;9:111–125. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zimrin AB, Villeponteau B, Maciag T. Models of in vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell differentiation on fibrin but not Matrigel is transcriptionally dependent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;213:630–638. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Helenius G, Johansson BR, Li JY, Mattsson E, Risberg B. Co-culture of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells affects gene expression of angiogenic factors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;89:1250–1259. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Korff T, Kimmina S, Martiny-Baron G, Augustin HG. Blood vessel maturation in a 3-dimensional spheroidal coculture model: direct contact with smooth muscle cells regulates endothelial cell quiescence and abrogates VEGF responsiveness. FASEB J. 2001;15:447–457. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0139com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harvey K, Welch Z, Kovala AT, Garcia JG, English D. Comparative analysis of in vitro angiogenic activities of endothelial cells of heterogeneous origin. Microvasc. Res. 2002;63:316–326. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2002.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Dewerchin M, Mackman N, Luther T, Breier G, Ploplis V, Muller M, Nagy A, Plow E, Gerard R, Edgington T, Risau W, Collen D. Insights in vessel development and vascular disorders using targeted inactivation and transfer of vascular endothelial growth factor, the tissue factor receptor, and the plasminogen system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997;811:191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miller JC, Pien HH, Sahani D, Sorensen AG, Thrall JH. Imaging angiogenesis: applications and potential for drug development. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005;97:172–187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McDonald DM, Choyke PL. Imaging of angiogenesis: from microscope to clinic. Nat. Med. 2003;9:713–725. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Milkiewicz M, Brown MD, Egginton S, Hudlicka O. Association between shear stress, angiogenesis, and VEGF in skeletal muscles in vivo. Microcirculation. 2001;8:229–241. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yoshimoto M, Kinuya S, Kawashima A, Nishii R, Yokoyama K, Kawai K. Radioiodinated VEGF to image tumor angiogenesis in a LS180 tumor xenograft model. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2006;33:963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Amyot F, Camphausen K, Siavosh A, Sackett D, Gandjbakhche A. Quantitative method to study the network formation of endothelial cells in response to tumor angiogenic factors. Syst. Biol. (Stevenage) 2005;152:61–66. doi: 10.1049/ip-syb:20045036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Polymeric system for dual growth factor delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sun Q, Chen RR, Shen Y, Mooney DJ, Rajagopalan S, Grossman PM. Sustained vascular endothelial growth factor delivery enhances angiogenesis and perfusion in ischemic hind limb. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:1110–1116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-5644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Springer ML, Ip TK, Blau HM. Angiogenesis monitored by perfusion with a space-filling microbead suspension. Mol. Ther. 2000;1:82–87. doi: 10.1006/mthe.1999.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lauffenburger DA, Chu LL, French A, Oehrtman G, Reddy C, Wells A, Niyogi S, Wiley HS. Engineering dynamics of growth factors and other therapeutic ligands. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996;52:61–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19961005)52:1<61::AID-BIT6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mahoney MJ, Saltzman WM. Controlled release of proteins to tissue transplants for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996;85:1276–1281. doi: 10.1021/js9601602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mac Gabhann F, Ji JW, Popel AS. Computational model of vascular endothelial growth factor spatial distribution in muscle and proangiogenic cell therapy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2(9):1107–1120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Radisic M, Deen W, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Mathematical model of oxygen distribution in engineered cardiac tissue with parallel channel array perfused with culture medium containing oxygen carriers. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H1278–H1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00787.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Filion RJ, Popel AS. Intracoronary administration of FGF-2: a computational model of myocardial deposition and retention. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H263–H279. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00205.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mac Gabhann YMF, Popel AS. Monte Carlo simulations of VEGF binding to cell surface receptors in vitro. BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2005;1746:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun SY, Wheeler MF, Obeyesekere M, Patrick CW. A deterministic model of growth factor-induced angiogenesis. Bull. Math. Biol. 2005;67:313–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bulm.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mac Gabhann F, Ji JW, Popel AS. VEGF gradients, receptor activation, and sprout guidance in resting and exercising skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:722–734. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00800.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kelm JM, Diaz Sanchez-Bustamante C, Ehler E, Hoerstrup SP, Djonov V, Ittner L, Fussenegger M. VEGF profiling and angiogenesis in human microtissues. J. Biotechnol. 2005;118:213–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ramakrishnan R, Cheung WK, Wacholtz MC, Minton N, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after single and multiple doses in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;44:991–1002. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Woo S, Krzyzanski W, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after intravenous and subcutaneous administration in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:1297–1306. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Freedman SB, Isner JM. Therapeutic angiogenesis for coronary artery disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;136:54–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-1-200201010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Simons M, Ware JA. Therapeutic angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev., Drug Discov. 2003;2:863–871. doi: 10.1038/nrd1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Langer R. Delivery systems for angiogenesis stimulators and inhibitors. EXS. 1992;61:327–330. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7001-6_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Patel ZS, Mikos AG. Angiogenesis with biomaterial-based drug- and cell-delivery systems. J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 2004;15:701–726. doi: 10.1163/156856204774196117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fischbach C, Mooney DJ. Polymeric systems for bioinspired delivery of angiogenic molecules. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2006;203:191–221. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Brey EM, Uriel S, Greisler HP, McIntire LV. Therapeutic neovascularization: contributions from bioengineering. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:567–584. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Biopolymeric delivery matrices for angiogenic growth factors. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2003;12:295–310. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(03)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.King TW, Patrick CWJ. Development and in vitro characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-loaded poly(dl-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/poly(ethylene glycol) microspheres using a solid encapsulation/single emulsion/solvent extraction technique. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., A. 2000;51:383–390. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<383::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Murphy WL, Peters MC, Kohn DH, Mooney DJ. Sustained release of vascular endothelial growth factor from mineralized poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2521–2527. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cleland JL, Duenas ET, Park A, Daugherty A, Kahn J, Kowalski J, Cuthbertson A. Development of poly-(d,l-lactide-coglycolide) microsphere formulations containing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor to promote local angiogenesis. J. Control. Release. 2001;72:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wong C, Inman E, Spaethe R, Helgerson S. Fibrin-based biomaterials to deliver human growth factors. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;89:573–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Steffens GC, Yao C, Prevel P, Markowicz M, Schenck P, Noah EM, Pallua N. Modulation of angiogenic potential of collagen matrices by covalent incorporation of heparin and loading with vascular endothelial growth factor. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1502–1509. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Augst AD, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 2006;6:623–633. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Silva EA, Mooney DJ. Spatiotemporal control of VEGF delivery from injectable hydrogels enhances angiogenesis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5:590–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lee KY, Peters MC, Anderson KW, Mooney DJ. Controlled growth factor release from synthetic extracellular matrices. Nature. 2000;408:998–1000. doi: 10.1038/35050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ishihara M, Obara K, Nakamura S, Fujita M, Masuoka K, Kanatani Y, Takase B, Hattori H, Morimoto Y, Ishihara M, Maehara T, Kikuchi M. Chitosan hydrogel as a drug delivery carrier to control angiogenesis. J. Artif. Organs. 2006;9:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s10047-005-0313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Young S, Wong M, Tabata Y, Mikos AG. Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules. J. Control. Release. 2005;109:256–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:1869–1879. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002;54:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mooney DJ, Baldwin DF, Suh NP, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Novel approach to fabricate porous sponges of poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) without the use of organic solvents. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1417–1422. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)87284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ratner BD. Reducing capsular thickness and enhancing angiogenesis around implant drug release systems. J. Control. Release. 2002;78:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dziubla TD, Lowman AM. Vascularization of PEG-grafted macroporous hydrogel sponges: a three-dimensional in vitro angiogenesis model using human microvascular endothelial cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., A. 2004;68:603–614. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bezuidenhout D, Davies N, Zilla P. Effect of well defined dodecahedral porosity on inflammation and angiogenesis. ASAIO J. 2002;48:465–471. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ennett AB, Kaigler D, Mooney DJ. Temporally regulated delivery of VEGF in vitro and in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., A. 2006;79:176–184. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kong HJ, Kaigler D, Kim K, Mooney DJ. Controlling rigidity and degradation of alginate hydrogels via molecular weight distribution. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1720–1727. doi: 10.1021/bm049879r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Boontheekul T, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Controlling alginate gel degradation utilizing partial oxidation and bimodal molecular weight distribution. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2455–2465. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lee KY, Bouhadir KH, Mooney DJ. Controlled degradation of hydrogels using multi-functional cross-linking molecules. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2461–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Peters MC, Isenberg BC, Rowley JA, Mooney DJ. Release from alginate enhances the biological activity of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 1998;9:1267–1278. doi: 10.1163/156856298x00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Ehrbar M, Raeber GP, Rizzi SC, Davies N, Schmokel H, Bezuidenhout D, Djonov V, Zilla P, Hubbell JA. Cell-demanded release of VEGF from synthetic, biointeractive cell ingrowth matrices for vascularized tissue growth. FASEB J. 2003;17:2260–2262. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1041fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Seliktar D, Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Wrana JL, Hubbell JA. MMP-2 sensitive, VEGF-bearing bioactive hydrogels for promotion of vascular healing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., A. 2004;68:704–716. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Sohier J, Vlugt TJ, Cabrol N, Van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Bezemer JM. Dual release of proteins from porous polymeric scaffolds. J. Control. Release. 2006;111:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Peirce SM, Price RJ, Skalak TC. Spatial and temporal control of angiogenesis and arterialization using focal applications of VEGF164 and Ang-1. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;286:H918–H925. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00833.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Cao R, Bråkenhielm E, Pawliuk R, Wariaro D, Post MJ, Wahlberg E, Leboulch P, Cao YH. Angiogenic synergism, vascular stability and improvement of hind-limb ischemia by a combination of PDGF-BB and FGF-2. Nat. Med. 2003;9:604–613. doi: 10.1038/nm848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chen RR, Silva EA, Yuen WW, Mooney DJ. Spatio-temporal VEGF and PDGF delivery patterns blood vessel formation and maturation. Pharm. Res. 2007;24:258–264. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Rowley JA, Madlambayan G, Mooney DJ. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Massia SP, Hubbell JA. Human endothelial cell interactions with surface-coupled adhesion peptides on a nonadhesive glass substrate and two polymeric biomaterials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., A. 1991;25:223–242. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820250209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1677–1686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kong HJ, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Quantifying the relation between adhesion ligand-receptor bond formation and cell phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:18534–18539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605960103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Tsang VL, Bhatia SN. Three-dimensional tissue fabrication. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:1635–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.La Van DA, McGuire T, Langer R. Small-scale systems for in vivo drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nbt876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Staples M, Daniel K, Cima MJ, Langer R. Application of micro- and nano-electromechanical devices to drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2006;23:847–863. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9906-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Santini JJT, Richards AC, Scheidt R, Cima MJ, Langer R. Microchips as controlled drug-delivery devices. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2000;39:2396–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Nanomedicine: developing smarter therapeutic and diagnostic modalities. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:1456–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]