Summary

Posttranslational arginylation mediated by arginyltransferase (Ate1) is essential for cardiovascular development and angiogenesis in mammals and directly affects the myocardium structure in the developing heart. We recently showed that arginylation exerts a number of intracellular effects by modifying proteins involved in the functioning of actin cytoskeleton and the events of cell motility. Here we investigate the role of arginylation in the development and function of cardiac myocytes and their actin-containing structures during embryogenesis. Biochemical and mass spectrometry analysis shows that alpha cardiac actin undergoes arginylation on multiple sites during development. Ultrastructural analysis of the myofibrils in wild type and Ate1 knockout mouse hearts shows that the absence of arginylation results in defects in myofibril structure that delay their development and affect the continuity of myofibrils throughout the heart, predicting defects in cardiac contractility. Comparison of cardiac myocytes derived from wild type and Ate1 knockout mouse embryos show that the absence of arginylation results in abnormal beating patterns. Our results demonstrate cell-autonomous cardiac myocyte defects in arginylation knockout mice that lead to severe congenital abnormalities similar to those observed in human disease, and outline a new function of arginylation in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton in cardiac myocytes.

Keywords: Protein arginylation, heart development, actin, posttranslational modifications, myofibrils, cardiac muscle

Introduction

Protein arginylation is a poorly understood posttranslational modification mediated by arginyltransferase Ate1 (Balzi et al., 1990) that transfers arginine (Arg) from tRNA onto proteins (Kaji et al., 1963; Soffer, 1968; Takao and Samejima, 1999). Ate1 is encoded by a single gene, highly conserved in evolution from yeast to human, and is expressed as one or more isoforms produced by alternative splicing in different mouse tissues (Kwon et al., 1999; Rai and Kashina, 2005; Rai, 2006). No other enzymes with arginyl transfer activity have been identified in eukaryotic species to date. While in yeast Ate1 gene is not essential for cell viability, Ate1 knockout in mice results in embryonic lethality and severe defects in cardiovascular development and angiogenesis (Kwon et al., 2002). Multiple proteins are arginylated in vivo (Bongiovanni et al., 1999; Decca et al., 2006a; Decca et al., 2006b; Eriste et al., 2005; Fissolo et al., 2000; Hallak and Bongiovanni, 1997; Kopitz et al., 1990; Lee et al., 2005), including 43 protein targets isolated from different mouse cells and tissues (Wong et al., 2007).

Mice with knockout of Ate1 die between days E12.5 and E17 in embryonic development with large hemorrhages, impairment of the embryonic angiogenesis, and severe heart defects that include underdeveloped myocardium, septation defects (ventricular and atrial septal defects, VSD and ASD, respectively), and non-separation of aorta and pulmonary artery (persistent truncus arteriosus, PTA) (Kwon et al., 2002). The underlying molecular mechanisms and cell lineage(s) responsible for these defects are unknown. It has been hypothesized that some, or all of these defects can be due to impaired embryonic cell migration during heart formation. VSD, ASD, and PTA defects are often observed in mice with knockout of genes that affect migration of cells of the neural crest lineage (Gitler et al., 2002) and cell adhesion (Conti et al., 2004; George et al., 1997; George et al., 1993; Tullio et al., 1997). Cells derived from Ate1 knockout embryos display severe defects in lamella formation that result in impairment of directional migration along the substrate, linked to arginylation of beta actin, a ubiquitously expressed nonmuscle actin isoform that plays a critical role in lamella formation and non-muscle cell locomotion (Karakozova et al., 2006). However, the question whether the heart defects seen in Ate1 knockout embryos are indeed linked to impairments in cell migration during development, or whether additional cell-autonomous changes in the cells composing the heart contribute to the Ate1 knockout phenotype, remains to be addressed.

It has been recently found that a number of proteins in embryonic and adult mouse tissues are arginylated (Wong et al., 2007). Among these a prominent arginylation substrate is alpha cardiac actin, the major component of the myofibrils in the cardiac muscle, whose arginylation is likely to affect myofibril development and function. It is likely that impairment of this arginylation in the Ate1 knockout mice would lead to defects in the myofibril development that can be seen by comparison of the hearts in wild type and Ate1 knockout mouse embryos and can shed light on the molecular role of arginylation in heart development and myofibril function.

To address the question of whether Ate1 knockout results in cell-autonomous changes in cardiac myocytes and whether arginylation plays a role in myofibril development and function, we performed characterization of embryonic actin by gel fractionation and mass spectrometry and found that alpha cardiac actin during development exists in a highly arginylated state and contains a total of four arginylated sites including two that were previously unknown. The four added Arg are likely to act in conjunction within the folded actin monomer to modulate actin polymerization and co-assembly with other myofibril proteins. Analysis of myofibril development at early stages of heart development, as well as between embryonic days E12.5 and E14.5, when the phenotypic changes in Ate1 knockout embryos become obvious, showed that lack of arginylation results in delayed myofibril formation and various structural myofibril defects that suggest impairment in cardiac contractility. Studies of cardiac myocytes in culture support these conclusions and suggest that arginylation plays a key role in the functioning of cardiac myocytes. These results demonstrate cell-autonomous changes in cardiac myocytes that develop in response to Ate1 knockout and suggest a key role of actin arginylation in the development and function of cardiac muscle in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Ate1 knockout mice

Mice with deletion of exons 2–4 of the Ate1 gene were newly rederived using the targeting vector and strategy described in (Kwon et al., 2002). PCR genotyping of mice and embryos used for heart and myocyte derivation was performed using a mixture of three primers: 5′-CTG TTC CAC ATA CAC TTC ATT CTC AG -3′, 5′-GGT GCA AGT TCC TGT CTA TT - 3′, and 5′ - AAT TGG AGG GGG ATA GAT AAG A - 3′ to detect products of 603 bp (for wild type allele) and 417 bp (for the knockout allele).

Actin fractionation and analysis

For 2D gel analysis, whole E12.5 embryonic hearts were washed in PBS, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, supplemented with 50 ul of 2× SDS sample buffer (5% SDS, 5% beta mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol and 60 mM Tris, pH 6.8 (Burgess-Cassler et al., 1989)), homogenized by grinding and pipetting and boiled for 10 min for the subsequent eletrophoretic fractionation. Complete dissolution of proteins was confirmed by centrifugation of the samples at 13,000g for 15 min and visual confirmation that no pellet was present in the tube. 2D gel electrophoresis was performed with SDS-boiled samples using carrier ampholines with isoelectrofocusing tube gels that enable isoelectrofocusing of samples prepared with SDS buffer as described in (Anderson and Anderson, 1978) by Kendrick Laboratories, Inc. (www.kendricklabs.com). Spots corresponding to individual actin isoforms were excised from dried Coomassie-stained gels and analyzed by mass spectrometry as described in (Karakozova et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007) for protein identification and mapping of the arginylation sites.

For the analysis of the protein composition of the myofibrils shown in Supplemental Figure 2, myofibril isolation procedure described in (Meng et al., 1996) was used. In brief, individual E12.5 embryonic hearts were homogenized in 20 volumes (per weight) of buffer I (39 mM sodium borate, 35 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, and 1mM DTT, pH 7.1) and centrifuged at 1500g for 12 minutes. The pellets were resuspended in 20 volumes of buffer II (39 mM sodium borate, 25 mM KCl, and 1mM DTT, pH 7.1) and centrifuged at 1500 g for 12 minutes. The pellets were further re-extracted for 30 minutes with TritonX-100 buffer (39 mM sodium borate, 25mM KCl, 1mM DTT and 1% triton X-100, pH 7.1) and centrifuged at 1500g for 12 minutes, followed by a wash with 20 volumes of suspension buffer (10mM Tris ,100mM KCl, 1mM DTT, pH 7.1) and centrifugation at 1500g for 30 minutes. The final pellets containing myofibrils were resuspended in 15 ul of 1× sample buffer and boiled for 15 minutes before loading on an SDS gel.

Gel scanning and densitometry for determination of the percentages of arginylated actin and the myosin to actin ratios in the myofibril preparations was performed on inverted black and white images of gels shown in Fig. 1 using ‘gray level’ quantification in Metamorph imaging software (Molecular Devices).

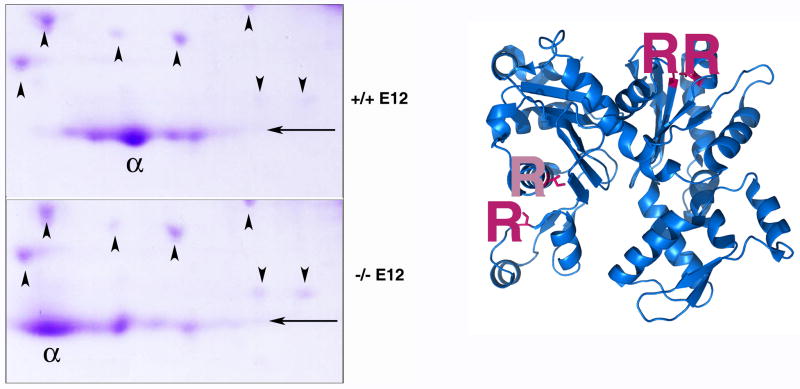

Figure 1. Alpha cardiac actin is arginylated in vivo.

Left, areas of a Coomassie stained 2D gel obtained by fractionation of the whole E12.5 mouse hearts from wild type (+/+, top) and knockout (−/−, bottom) embryos under a shallow pH gradient (pH 4–8) to enable separation of individual actin isoforms. pH increases left to right. Arrowheads indicate the position of spots, which were used for the horizontal alignment of the two gels to enable observation of gel shifts of individual actin spots. Arrows indicate the position of the 43 kDa marker at the actin molecular weight. ‘Alpha’ (α) symbol denotes the position of alpha cardiac actin, as identified by mass spectrometry. Right, 3D structure of an alpha cardiac actin monomer (PDB identifier 1J6Z) with posttranslationally arginylated sites indicated in pink within the blue actin backbone anddenoted with capital R. Pale pink R indicates a site, for which the mass spectrum is not shown and will be described elsewhere.

Electron microscopy

Whole mouse embryos at E9.5 and hearts excised from E12.5 and E14.5 mouse embryos were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in buffer C (0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4) overnight at 4oC, followed by 2 × 10 min washes in buffer C and postfixation in 2% osmium tetroxide in buffer C. For staining, fixed embryos/hearts were washed 2 × 10 min in buffer C and 1 × 10 min in dH2O, incubated 1 hour at room temperature in 2% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and washed 2 × 10 min in dH2O. For embedding, stained embryos/hearts were dehydrated 2 × 5by incubation for 10 min each in 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100% EtOH, followed by min incubations in propylene oxide (PO), overnight incubation in 1:1 PO:Epon, and 1 day in 100% Epon. Epon-embedded embryos/hearts were kept for 2 days at 60oC for Epon polymerization, sectioned, stained with 1% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol, and 2% w/v solution of bismuth subnitrite at 1:50 dilution, and overlayed onto formvar-coated grids for electron microscopy. 4 embryos at E 9.5 and 4 hearts at E12.5 (2 wild type and 2 knockout each) and 6 hearts at E14.5 (3 wild type and 3 knockout) were used for measurements and observations shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

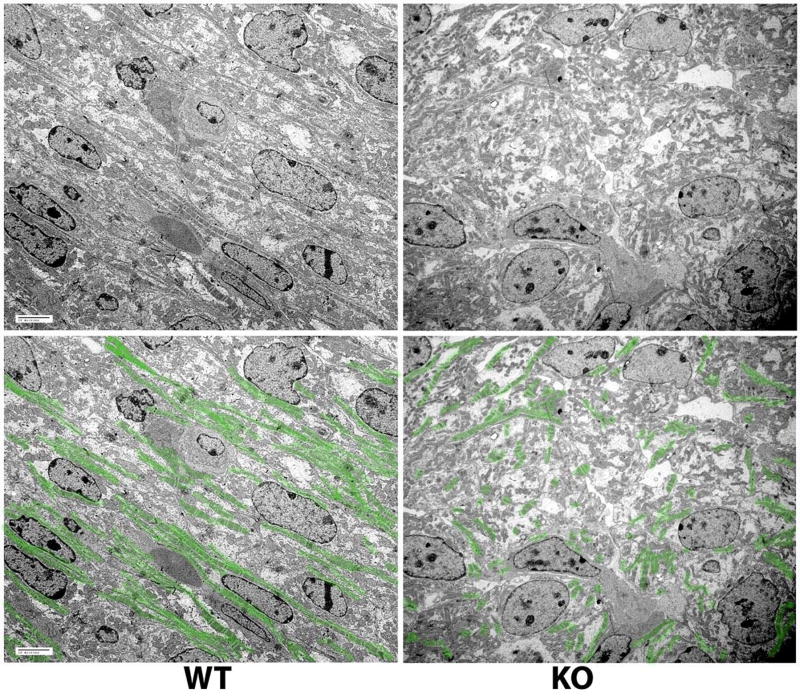

Figure 2. Ate1 knockout results in delayed development and disorganization of cardiac myofibrils.

Electron microscopic images of sections of wild type (left) and knockout (right) E14.5 hearts at 2500× magnification. Copies of the original images with myofibrils highlighted in green are shown on the bottom. While in wild type at E14.5 myofibrils are prominent and oriented along the axis of the heart muscle, in knockout at the same stage myofibrils are much less abundant and difficult to trace over continuous distances, suggesting a defect in overall myofibril organization and cardiac contractility. Bars, 10 μm.

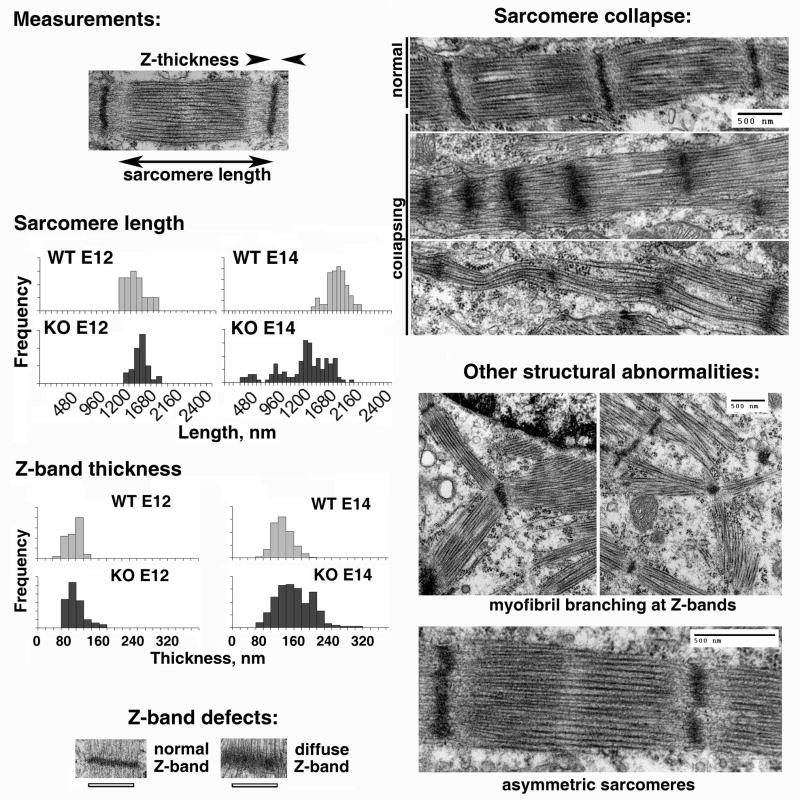

Figure 3. Ate1 knockout results in defects in the sarcomeric structure of cardiac myofibrils.

Left top, wild type sarcomere with measured parameters indicated. Left middle, frequency distribution of sarcomere length and Z-band thickness in wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) hearts at embryonic days E12.5 (E12) and E14.5 (E14). While in wild type and E12.5 hearts both sarcomere length and Z-band thickness are relatively constant with small variations due to differences in the contractile state of individual myocytes, in knockout hearts at later stages (E14.5) the frequency distribution of both parameters becomes wider, suggesting disorganization of the sarcomeres. Left bottom and right top panels illustrate the defects in Z-band thickness and sarcomere length, respectively. Average sarcomere lengths were 1389 +/− 141 nm (WT E12, n=27), 1490 +/− 101 nm (KO E12, n=39), 1682 +/− 116 (WT E14, n=116) and 1179 +/− 199 (KO E14, n=124). Average Z-band thicknesses were 86 +/− 19 nm (WT E12, n=27), 87 +/− 23 nm (KO E12, n=39), 120 +/− 23 (WT E14, n=116) and 142 +/− 36 (KO E14, n=124) (errors represent SD). Bottom right, examples of other defects in myofibril structure seen in Ate1 knockout hearts, including myofibril branching at Z-bands and asymmetric sarcomeres, in which the density of the filaments on the two sides is markedly different. Bars, 500 nm.

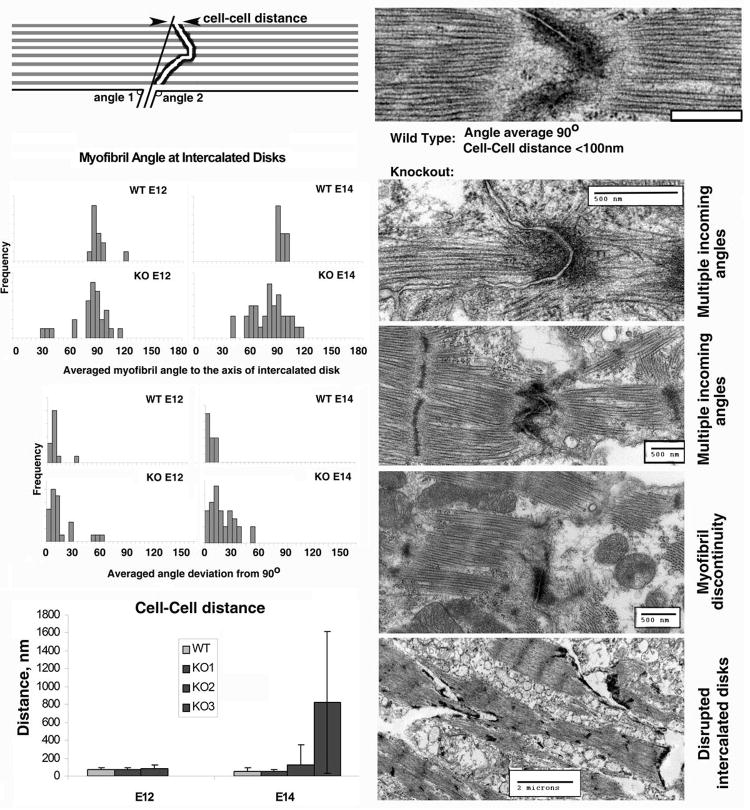

Figure 4. Ate1 knockout results in defects in myofibril continuity at intercataled disks.

Left top, an illustration of the parameters measured. Left middle, frequency distribution of myofibril angle average at each intercalated disk (top diagram) and deviation of this angle from 90° (bottom diagram). Left bottom, cell-cell distance averaged for all wild type hearts together (light gray bars) and for individual knockout hearts (dark gray bars), sorted by embryo age. As the severity of the knockout phenotype progresses, average cell-cell distance as well as the standard deviation between distances in a single heart increase, as seen at E14 for the three KO hearts shown. Right column, examples of intercalated disks in wild type (top) and knockout (bottom four panels). Abnormalities at intercalated disks included disorganization of the myofibrils, resulting in angle deviations for incoming filaments from 90° (top two images), myofibril asymmetry on two sides of intercalated disk (middle images), and disruption of the cell-cell contacts at intercalated disks (bottom image). Bars, 500 nm for top images and 2 μm for the bottom right image.

Cardiac myocyte derivation and beat measurements

For cardiac myocyte derivation, whole hearts from E12.5 embryos were washed with warm PBS, placed into 200 ul of pre-warmed 1% trypsin in PBS and incubated at 37ºC for ~5 minutes. After digestion, heart tissue was gently pipetted up and down until the visually large aggregates were broken apart, cell suspension was diluted with 1ml of DMEM:F10 culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS, centrifuged for 5 minutes at ~1000 RPM, resuspended in of the same medium, and plated onto 3.5 cm collagen coated glass bottom dishes (Matek). Cells were incubated overnight in culture for attachment and spreading. For myocyte beat measurements, time-lapse videos of individual myocytes or islands were obtained over 1 min at ½ sec time intervals (120 frames) using phase contrast 10x, 20x or 40x objectives and Orca AG digital camera (Hamamatsu). In each video, beats of individual cells or isolated islands were measured by selecting a 10×10 pixel region in the cell area where gray value (image intensity) displays obvious changes during each contraction (as shown in Fig. 5, top right), and total gray value over time in this region was measured using Metamorph imaging software (Molecular Devices). Time intervals between the centers of gray value peaks determined automatically after smoothing the baseline and scaling up the peaks were used for frequency diagrams and calculation of means and ratios shown in Fig. 5. For measurements of calcium changes during beats, media in the dishes with cultured myocytes was supplemented with 2.5 μM cell-permeable Fluo-4 fluorescent calcium indicator dye (Invitrogen), followed by 30 min incubation for dye loading. Individual cells and islands were then placed into fresh media and imaged by phase contrast time lapse over 25 sec, acquired at 4 frames per second, followed by imaging of the same field in the fluorescent channel for the same time interval. Calcium change periodicity was measured by changes in light intensity (gray levels) in a 10×10 pixel region located in the center of a beating cell and intervals between peaks were determined and compared to those obtained during phase contrast imaging of the same cells for the correlation plot shown in Fig. 5.

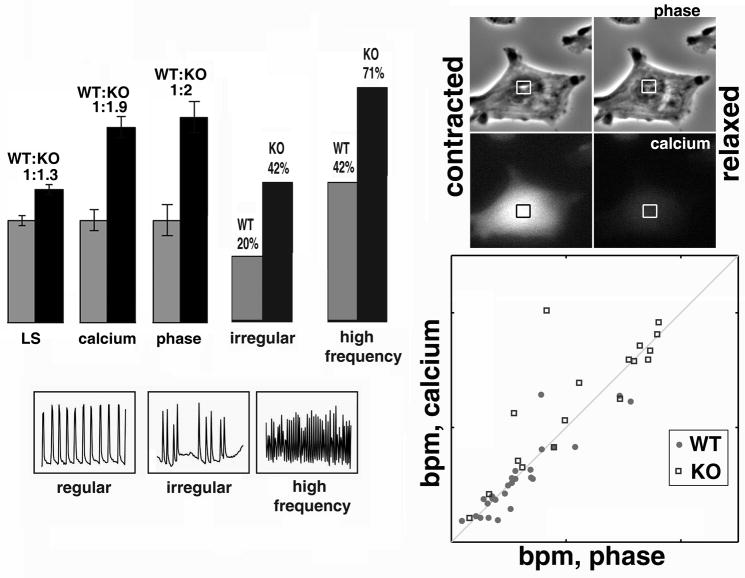

Figure 5. Ate1 knockout results in defects in cardiac myocyte beating patterns.

Left top, comparison of mean beats per minute (bpm), percentage of cells beating with high frequency, and percentage of cells with visible irregularities in the beating patterns between wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) cultured myocytes derived from E12.5 embryonic hearts. Calculations were made for 164 WT and 233 KO cells/islands for the left set of bars at low sampling rate (LS, 2 frames per second), 28 WT and 17 KO cells/islands for the next two sets of bars (phase and calcium, sampled at 4 frames per second for the same cell/islands in phase contrast and fluorescence (calcium) channel), and 194 WT and 250 KO cells for the two right-hand sets of bars. See the images of individual beating curves in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3. Left bottom, examples of beating frequency curves, which were considered as regular, irregular, and high frequency during manual calculation of curves shown in Supplemental Figures 2, 3, and 4 to derive the percentages shown above. Right top, illustration of the beat and calcium wave measurements as total gray level in a square region taken in the area of the beating cell with most visible changes (usually, the center). Right bottom, correlation plot between the physical beats observed in phase contrast (x axis) and calcium changes over time in the same cells (y axis) shows that for the most part beats are correlated with calcium waves in both cultures. See Supplemental Figure 4 for beating curves obtained by imaging of the same cells by phase contrast and Fluo4 Ca fluorescence.

Results

Alpha cardiac actin is arginylated in vivo on multiple sites

We have recently found that actin is arginylated in vivo and that this arginylation regulates its key properties and functions in the actin cytoskeleton (Karakozova et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007). One of the two actin isoforms shown to undergo arginylation is alpha cardiac actin – a key heart protein and the major component of the cardiac myofibrils. To address the question whether alpha cardiac actin is arginylated during embryogenesis and to estimate the percentage of actin arginylated in vivo, we fractionated whole mouse hearts derived from E12.5 wild type and Ate1 knockout mouse embryos by 2D gel electrophoresis under pH gradient that allows separation of actin isoforms (Fig. 1, left panel), and identified actin isoform composition of the individual spots by mass spectrometry. Actin isoforms (alpha, beta, and gamma) are over 99% identical to each other, with small variations in aminoacid composition that leads to shifts in the isoelectric points (Otey et al., 1987; Otey et al., 1986; Rubenstein and Spudich, 1977; Vandekerckhove and Weber, 1978), which can be seen when fractionation is performed under a shallow pH gradient (pH range 4–8); alpha actin is the most acidic and appears as the leftmost spot(s) on such gels.

While adult hearts express predominantly alpha cardiac actin, more actin isoforms are expressed simultaneously during embryogenesis (Hayward and Schwartz, 1986; Otey et al., 1988; Sassoon et al., 1988), resulting in multiple spots being present in the appropriate range of the gel in addition to the major, alpha actin spot (Fig. 1, left, top panel). Comparison of the actin spot composition in wild type and Ate1−/− E12.5 hearts revealed a striking change in the position of the major isoform spot (marked α on the two panels in Fig. 1), which was significantly shifted to the more acidic range (left), consistent with the loss of several positive charges. Since Arg is highly positively charged, and addition of Arg to proteins is expected to result in an isoelectric point shift toward the basic range, the gel shift observed between wild type and Ate1 knockout hearts is consistent with addition of several positively charged Arg to the wild type actin molecule. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the major actin spots excised from the gels similar to those shown in Fig. 1 by mass spectrometry, using high accuracy LTQ-Orbitrap MS instrument and database search algorithm to look for addition of an extra Arg to the N-terminus of the peptides (Wong et al., 2007). While sequence coverage of gel-excised spots was significantly lower than for samples analyzed in solution, analysis of actin spots excised from several different gels resulted in identification of two previously unknown arginylation sites, one at isoleucine 87 (denoted in pale pink on the diagram in Fig. 1, right; this site will be described in detail elsewhere), and one at glycine 152 (see Supplemental Fig. 1 for the mass spectrum of the corresponding peptide). Remarkably, although both sites are located far from the N-terminus and are expected to require a preceding proteolytic cleavage to become accessible for arginylation, they were found in actin excised from an intact 2D gel spot (43 kDa), suggesting that the molecule was held together in SDS PAGE after the processing. The chemistry behind this reaction and the processing that leads to intrachain cleavage and arginylation without destroying the integrity of the molecule will be described elsewhere.

Mapping of all four of the identified arginylated sites onto the actin 3D structure (PDB identifier 1J6Z (Otterbein et al., 2001)) revealed that all these sites are accessible on the surface of the folded subunit, but some sites may not be accessible after polymerization (the two sites on the top), suggesting that the modification of these sites could occur after the subunit folding but before its incorporation into the polymer. The identified sites are located pairwise on the actin surface, with two arginylated residues directly facing each other in the folded structure (marked in pink within the blue chain of the actin backbone). Insertion of Arg into these positions be predicted to affect the molecular structure of the actin monomer, its polymerization properties, and interaction with other proteins in the myofibril.

Estimation of the arginylation-dependent gel shifts of the alpha cardiac actin shown in figure 1 by gel densitometry suggests that as much as 40% of total embryonic heart actin, and 50% of the alpha actin, is arginylated in vivo. Thus, alpha cardiac actin in embryonic hearts exists in a highly arginylated state and Ate1 knockout results in abolishment of actin arginylation, expected to result in significant structural and functional changes in the actin molecule.

Arginylation regulates myofibril assembly, structure, and continuity throughout the heart

To test whether arginylation knockout results in defects in myofibril structure and/or assembly at the onset and progression of the phenotypic changes in Ate1−/− embryos, we analyzed sections of fixed hearts derived from E12.5 and E14.5 wild type and knockout littermate embryos by electron microscopy. These stages were chosen because at E12.5 Ate1−/− embryos appear to be phenotypically normal, and therefore only the most significant early myofibril defects, if any, are expected to be seen, while at E14.5 most knockout embryos look grossly abnormal and some of them start to die, so that if any myofibril defects indeed develop in response to the Ate1 knockout, they would be highly prominent at this point.

Examination of the heart structure at lower magnification (×250, not shown), confirmed that Ate1 knockout hearts, consistent with previously reported observations, had thin walls due to the reduced size of the compact zone of the myocardium (Kwon et al., 2002). Higher magnification views of the large areas of the heart (×2500, Fig. 2) revealed significant structural changes in Ate1 knockout hearts compared to their wild type counterparts. While in wild type hearts development of highly organized, continuous myofibrils prominently progressed from E12.5 to E14.5, in Ate1 knockout this development appeared to be delayed, resulting in scarce, disorganized myofibrils whose continuity could not be traced through multiple myocytes (Fig. 2, right). The prominence and severity of these defects varied between individual embryos and across the heart areas analyzed, but all the hearts used in this analysis displayed similar trends. In the most severe cases, observed in hearts taken from the E14.5 embryos with prominent phenotypic changes (reduced size, paleness, and hemorrhages as described in (Kwon et al., 2002)), the myofibril structure and connection between the myocytes were disrupted, suggesting that such hearts would likely not be able to function normally. Overall, the observed changes suggested that Ate1 knockout resulted in the delayed development, disorganization of the myofibrils and disruption of their continuity between interconnected cells, predicted to affect contractility within the heart muscle.

To address the question whether such global changes in the myofibril layout are accompanied by ultrastructural changes in the myofibrils, we first compared protein composition of the myofibrils isolated from wild type and Ate1 knockout hearts taken at E12.5. While no consistent changes were observed, the preparations from knockout hearts were somewhat more variable and the ratio of the myosin to actin quantified by gel densitometry was slightly lowered compared to wild type (Supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that at this stage the myofibrils in the knockout hearts may be more structurally unstable than control. This instability may be due either to the specific structural changes in the myofibrils themselves or to the general onset of heart failure because of Ate1 knockout.

We next analyzed higher magnifcation images of the sarcomeres and intercalated disks in wild type and mutant hearts (Figs 3 and 4). Several structural features of the myofibrils and intercalated disks were evaluated quantitatively, including sarcomere length and Z-band thickness (measures of sarcomere structure, Fig. 3), angle of myofibrils and their composing filaments at intercalated disks (a measure of myofibril continuity throughout the heart), and cell-cell distance at intercalated disks (a measure of heart muscle integrity) (Fig. 4). In addition, the general appearance of the myofibrils was evaluated. Only the fully developed, structurally distinct myofibrils were evaluated in both conditions, so the analysis presented in Figs 3 and 4 does not reflect any measures of the rate of myofibril development, which was difficult to evaluate due to possible variations in the areas of the heart muscle used for sectioning in each heart.

Several prominent defects were observed in the myofibrils with the progression of Ate1 knockout-related phenotypic changes. While at E12.5 most of the sarcomeres and Z-bands in fully developed myofibrils appeared normal, at E14.5, hearts with more severe defects showed sarcomere collapse (Fig. 3), with progressive decrease of the length of individual sarcomeres and the diffusion of the Z-bands in a way that suggested disconnection of the Z-bands from the myofibrils. Some of the myofibrils became wavy and uneven, with prominent loss of Z-bands and fraying of the filaments out of the sarcomeres (bottom image in the top right panel on Fig. 3). A variety of other structural abnormalities was observed in individual cases, including myofibril branching at Z-bands, asymmetric sarcomeres with different apparent density of filaments on two sides of the same sarcomere (Fig. 3, bottom right panels), and patchy or missing Z-bands (not shown; also observed in wild type, but more often seen in knockout).

Defects were also seen at intercalated disks, which serve as the sites of connection of the myofibrils between the two neighboring myocytes and ensure the myofibril continuity throughout the heart. First, in most of the observed cases, including E12.5 hearts where other ultrastructural features were apparently normal, the filaments within a myofibril came into an intercalated disk at different angles, resulting in tapered (E12.5 and E14.5), frayed and/or disoriented (E14.5), or disconnected (i [a-z]. [a-z]., missing myofibril on one side of the intercalated disk, E14.5) morphology (Fig 4, bottom right panel, top three images) that suggested structural and functional discontinuity of the myofibrils between myocytes. In more severe cases, disruption of the intercalated disks themselves was observed (Fig 4, bottom right panel, bottom image). All these changes suggest contractility defects and disconnection between individual myocytes in the myocardium.

To further address the question whether the myofibril defects in Ate1−/− hearts are accompanied by a delay in myofibril development, we analyzed myofibril ultrastructure in the hearts of Ate1−/− embryos at earlier stages (embryonic day E9.5). At these stages no gross phenotypic changes in Ate1−/− embryos have been reported, however Ate1 expression is at its peak (Kwon et al., 2002) and therefore Ate1-related developmental defects should already be initiated. Consistent with the earlier studies (Kwon et al., 2002), no gross morphological changes were seen in E9.5 Ate1 −/− hearts compared to control. Both types of hearts contained prominent myofibrils as well as disarrayed myofibril-like structures, indicating that at this stage the development of the heart muscle is still ongoing. Comparison of the ‘least developed’ and the ‘most developed’ myofibrils seen in both types of embryos at this stage (Supplemental Figure 3) suggested that in Ate1 knockout mice myofibrils were thinner than in wild type and contained smaller amount of prominent Z-bands. To quantify this defect, we measured the length of the Z-bands (a measure of the myofibril thickness and therefore of the extent of myofibril development) in both types of hearts at E9.5 and E14.5 and compared the distributions of Z-band lengths in wild type and knockout at these stages. We found that while the length of the Z-bands increased considerably at later developmental stages, they were consistently shorter in Ate1−/− compared to wild type; this effect was especially prominent at E9.5, where the peak Z-band lengths were approximately 300 nm in wild type versus 200 nm in Ate1 knockout (Supplemental Figure 3). These results suggest that in addition to the ultrastructural changes in the myofibrils seen at later stages, the myofibril development in Ate1 knockout embryos is also delayed.

Thus, we find that Ate1 knockout results in delayed myofibril development, changes in the sacromere structure, and discontinuity of the myofibrils throughout the heart.

Arginylation regulates cardiac myocyte contractility in culture

To address the question whether the observed myofibril defects result in changes in the contractility of the cardiac myocytes, we isolated myocytes from E12.5 wild type and Ate1 knockout embryos and observed their spontaneous contractility in a tissue culture dish. In both cultures, two types of cells were present: flat, well-spread and polarized fibroblasts, and less spread, mostly hexagonally-shaped myocytes that often formed small islands with two or more cells clustering together. Most of the cells with myocyte morphology exhibited spontaneous contractility during the first 2–3 days in culture – the time interval used for the analysis. Fewer myocytes appeared to be beating in the knockout cultures, but this effect was not quantified because of the lack of criteria for a formal quantitative distinction between myocytes and non-myocyte cells in culture. After a few days in culture most of the Ate1 knockout myocytes ceased to beat, while in control cultures many more cells were still beating (suggesting that the wild type cells are ‘sturdier’ to the culture conditions and/or more capable of continuous beating), but since by that time the culture dish was usually overgrown with fibroblasts and cells of the myocyte morphology were difficult to identify, this effect was not quantified.

To measure the beating rates of individual myocytes and myocyte islands in culture, we made time-lapse movies of beating myocytes taken at 1/2s intervals over the course of 1 min in both cultures during the first two days after isolation, and measured the light intensity changes in phase contrast time lapse images over time (see Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 for the normalized plots of gray level changes over time for individual wild type and knockout cells/islands). Since this relatively low sampling rate may have precluded us from measuring the actual beating rate at higher frequencies (>60 bpm), we also manually calculated the amount of cells beating at high frequency, and the amount of cells displaying visibly irregular beating patterns with variable intervals and strength between individual beats (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

In both cultures, the range of beating frequencies of individual cells and islands and the regularity of beats varied greatly (see Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 for wild type and knockout beating curves), however while in the wild type cultures many cells were beating regularly at fairly slow rate (10–20 bpm, Fig. 5 and Supplemental Figure 2), in the knockout cultures a considerable number of cells beat at high frequency (>50 bpm, Fig. 5 and Supplemental Figure 2), elevating the mean bpm by a statistically significant number (Fig. 5 left and Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). The range of bpm observed in individual cells or islands displayed a somewhat wider distribution in the knockout cultures, but the difference was not statistically significant (not shown), however the percentage of high frequency-beating cells and cells with visible irregularities in the beating curves, calculated by manual counting of curves shown in Supplemental Figures 2, 3, and 4, varied considerably between the two cultures, with Ate1 knockout cells having a significantly higher percentage of both high frequency and irregularly beating cells compared to wild type (Fig. 5, middle). In addition, visual observations suggested that knockout cells and islands appear to contract more locally, with variations throughout the cell areas, suggesting local ‘twitching’ rather than a cell-wide contraction, in agreement with the defects in myofibril continuity seen at the ultrastructural level. These observations suggest that the increased occurrence of high frequency beats in the knockout cultures could reflect abnormal, fibrillating behavior of the cells, however this effect was not quantified.

To confirm that the physical beating frequency measured in our experiments correlates with the changes in intracellular Ca2+, we performed measurements of calcium waves (using Fluo-4 Ca2+ vital dye) and physical beats (using light intensity measurements of phase contrast images) in the same cells and/or islands and plotted the correlation between the two measurements (Fig. 5, right). We find that in most wild type and knockout cells beats and calcium waves show a good correlation, suggesting that changes in the beating frequencies seen in the knockout cells, even if originated by structural defects in the myofibrils, are tied into the calcium-dependent regulation. To minimize the UV exposure for live cells in culture, these measurements were performed at higher sampling rate (4 frames per second over 25 seconds), resulting in an elevated average bpm value for both cell types (not shown) and the elevated ratio of beating frequencies between wild type and knockout compared to those measured in the previous set of experiments (Fig. 5, left). This difference suggested that the earlier measurements, taken at lower sampling rate, may not have reflected the real beating frequencies of the cultured myocytes. The rates detected in our studies are similar to those seen by other researchers studying myocyte beats in culture, but since mouse hearts in vivo beat at much higher frequencies, over 300 bpm (Mai et al., 2004), it is possible that sampling rates in time lapse imaging of cultured cells precludes accurate measurements of the beating rate. For this reason, actual bpm values were not used in our analysis, and only the bpm ratios between wild type and knockout cultures are shown.

Thus, in agreement with our ultrastructural data, we find that Ate1 knockout results in changes in the contractility and beating patterns of cardiac myocytes, suggesting corresponding changes in the cardiac contractility in vivo.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates cell-autonomous defects in cardiac myocytes that develop in embryogenesis after the knockout of arginyltransferase Ate1 and affect myofibril development and structure, myocardium integrity, and myocyte contractility. While it has been previously known that Ate1 knockout results in significant defects in heart development and the reduced number of cells composing the heart walls, this is the first demonstration that some of the Ate1-regulated defects are directly associated with the defects in the cells composing the myocardium and responsible for heart contractility.

We have previously shown that two actin isoforms, beta and alpha cardiac, are arginylated in vivo (Karakozova et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007), and both isoforms are present in the developing heart. In this study we identify two new sites of arginylation on alpha cardiac actin and provide a possible functional correlation between alpha actin arginylation and myofibril development and function. Our data suggest that an extremely high percentage of cardiac actin (~50%) is arginylated, supporting the possibility that actin arginylation is critical for the myofibril integrity. It has been previously shown that substitution of alpha cardiac actin with gamma enteric muscle isoform (presumed to be non-arginylated) leads to altered mechanochemical properties of myofibrils isolated by detergent extraction of the heart muscle (Martin et al., 2002). While gamma enteric smooth muscle actin could hypothetically become partially arginylated during this substitution, this finding is overall consistent with our data that actin arginylation state and the identity of the N-terminal actin sequence is important for myofibril function. Further, our data suggest a direct role of arginylation in the regulation of actin during myofibril assembly and heart development.

Two of the four arginylated sites were identified in the actin polypeptides of intact size isolated from SDS gel after electrophoresis, suggesting that these modifications exist within the intact, folded actin molecule that maintains its integrity in SDS PAGE, and do not result in protein degradation or disassembly. The chemistry and enzymology of this reaction remains to be studied. The position of the arginylation sites in the actin 3D structure (Fig. 1) suggests that arginylation of one, or more of these sites would significantly alter actin polymerization properties and its ability to associate with other subunits during polymerization. Since the arginylated (Ate1-positive) state of actin is the wild type state, it is logical to assume that the absence of arginylation would result in the reduction of the ability of actin monomers to polymerize and/or interact with other actin-binding proteins, likely by abolishment of Arg residues from key positions within the molecule.

Our findings that myofibril development is delayed at as early as E9.5 suggest that Ate1 phenotypic changes begin much earlier than previously observed. It is conceivable that underdeveloped myofibrils, forced to contract under duress during growth and development of the embryo, become more and more abnormal as the development progresses. Such strain-dependent progression would also explain the variability of the Ate1-dependent myofibril defects. Indeed, thicker, better developed, myofibrils can endure longer, while thinner myofibrils disintegrate faster, leading to a variety of phenotypes both in the whole embryos and in individual myofibrils.

The timing of the myofibril defects seen in our study is consistent with the timing of other phenotypic changes in Ate1 knockout mice, which become apparent after day E12.5, closer to E14.5. While some of the defects described in the current work (disruption of intercalated disks) might constitute secondary defects due to the loss of the heart integrity, possibly preceding death, others (myofibril disorganization, sarcomere collapse, and Z-band diffusion) are likely to be primary defects due to the lack of arginylation of the major structural components of the myofibrils. Since a prominent peak of Ate1 expression is observed at E8–E9, after which Ate1 expression goes down, and the phenotypic changes take another 3–4 days to develop (Kwon et al., 2002), it is conceivable that E8–E9 mark the timing in development when a major quantity of myofibril proteins are arginylated and stocked up for further use. Actin is a good candidate for this type of regulation, since it is a highly abundant highly stable protein and a major structural component of the myofibrils and it has been found in our study to be arginylated in embryogenesis to a significant extent, however other proteins may also undergo similar regulation.

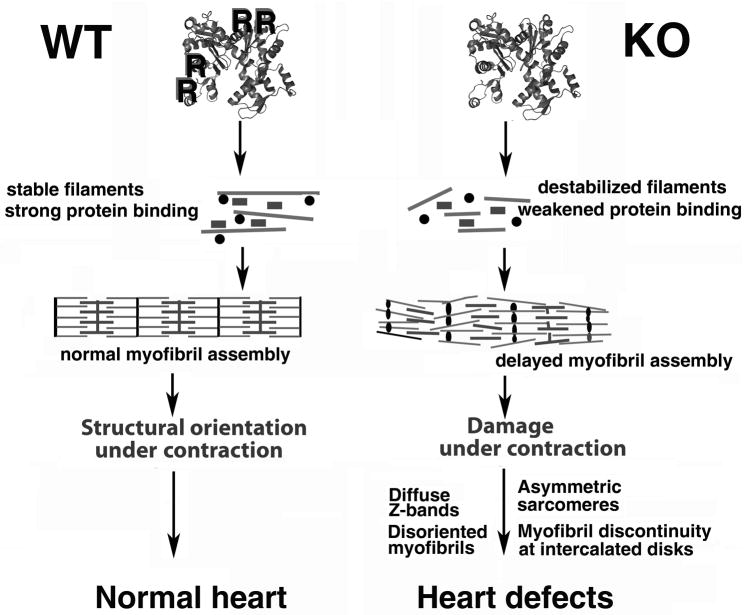

Among the current models of myofibril assembly during development, the more favorable model suggests their formation from premyofibrils by association of cytoplasmic actin filaments into minisarcomeres that later align into nascent myofibrils and further mature into myofibrils (LoRusso et al., 1997; Rhee et al., 1994; Sanger et al., 2000; Sanger et al., 2005). Lack of arginylation of actin and other myofibril components could conceivably affect one or more stages in this process, by slowing the polymerization of the initial actin filaments, enforcing their abnormal aggregation instead of normal association, or affecting their interaction with other important proteins that form the core of the myofibril structure (myosin II, capZ, alpha-actinin, troponins, tropomyosin, and others). In addition to alpha cardiac actin, our previous work showed that talin (that participates in membrane association of premyofibril complexes) as well as spectrin and filamin, generally responsible for assembly of actin-containing structures, are also targets for arginylation in vivo (Wong et al., 2007). We believe that a combination of these factors leads to a delay in the myofibril assembly (Fig. 6), resulting in fewer myofibrils formed in the Ate1 knockout hearts at the same embryonic stage as the control. Since these myofibrils receive the same contractility signals as the wild type heart (as follows from our data, Fig. 5, right), underdeveloped myofibrils under stress are more likely to develop structural abnormalities, eventually leading to their collapse and disintegration.

Figure 6. Model of the regulation of myofibril assembly and function by arginylation.

In wild type (WT) arginylated actin assembles into stable filaments and eventually into normal myofibrils. In Ate1 knockout, unarginylated actin forms destabilized filaments, resulting in delayed myofibril development and profound structural defects.

Our studies predict that cell-autonomous regulation of cardiac myocytes by arginylation is essential for myofibril stability, heart integrity, and mechanical continuity of the contraction throughout the myocardium. Changes in these processes constitute the underlying causes of congenital heart abnormalities and heart disease in humans. Studies of their regulation by arginylation are an emerging field, promising to uncover new molecular mechanisms of heart development and function in normal physiology and disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Neelima Shah and Ray Meade for heart sectioning and assistance with electron microscopy, Dr. Roberto Dominguez for help with actin structure analysis and preparation of Fig. 1, right panel, Jon Johansen and the staff of Kendrick Laboratories, Inc. for 2D gel electrophoresis, Dr. Bruce Freedman for helpful suggestions on calcium imaging, Drs. Howard Holtzer, Clara Franzini-Armstrong, John Murray, members of the Pennsylvania Muscle Institute and A. Kashina’s lab for helpful discussions, and Drs. Sougata Saha and Sat oshi Kurosaka for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant 5R01HL084419 and awards from WW Smith Charitable Trust and Philip Morris Research Management Group to AK and NIH P41 RR011823 to JRY.

References

- Anderson NG, Anderson NL. Analytical techniques for cell fractions. XXI. Two-dimensional analysis of serum and tissue proteins: multiple isoelectric focusing. Anal Biochem. 1978;85:331–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzi E, Choder M, Chen WN, Varshavsky A, Goffeau A. Cloning and functional analysis of the arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase gene ATE1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7464–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni G, Fissolo S, Barra HS, Hallak ME. Posttranslational arginylation of soluble rat brain proteins after whole body hyperthermia. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:85–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<85::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Cassler A, Johansen JJ, Santek DA, Ide JR, Kendrick NC. Computerized quantitative analysis of coomassie-blue-stained serum proteins separated by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Clin Chem. 1989;35:2297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti MA, Even-Ram S, Liu C, Yamada KM, Adelstein RS. Defects in Cell Adhesion and the Visceral Endoderm following Ablation of Nonmuscle Myosin Heavy Chain II-A in Mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41263–41266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decca MB, Bosc C, Luche S, Brugiere S, Job D, Rabilloud T, Garin J, Hallak ME. Protein arginylation in rat brain cytosol: a proteomic analysis. Neurochem Res. 2006a;31:401–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-9037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decca MB, Carpio MA, Bosc C, Galiano MR, Job D, Andrieux A, Hallak ME. Post-translational arginylation of calreticulin: A new isospecies of calreticulin component of stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2006b doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608559200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriste E, Norberg A, Nepomuceno D, Kuei C, Kamme F, Tran DT, Strupat K, Jornvall H, Liu C, Lovenberg TW, et al. A novel form of neurotensin post-translationally modified by arginylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35089–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fissolo S, Bongiovanni G, Decca MB, Hallak ME. Post-translational arginylation of proteins in cultured cells. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:71–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1007539532469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Baldwin HS, Hynes RO. Fibronectins Are Essential for Heart and Blood Vessel Morphogenesis But Are Dispensable for Initial Specification of Precursor Cells. Blood. 1997;90:3073–3081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development. 1993;119:1079–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Brown CB, Kochilas L, Li J, Epstein JA. Neural crest migration and mouse models of congenital heart disease. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2002;67:57–62. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallak ME, Bongiovanni G. Posttranslational arginylation of brain proteins. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:467–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1027315912242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward L, Schwartz R. Sequential expression of chicken actin genes during myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1485–1493. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji H, Novelli GD, Kaji A. A Soluble Amino Acid-Incorporating System from Rat Liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;76:474–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakozova M, Kozak M, Wong CC, Bailey AO, Yates JR, 3rd, Mogilner A, Zebroski H, Kashina A. Arginylation of beta-actin regulates actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Science. 2006;313:192–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1129344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopitz J, Rist B, Bohley P. Post-translational arginylation of ornithine decarboxylase from rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1990;267:343–8. doi: 10.1042/bj2670343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YT, Kashina AS, Davydov IV, Hu RG, An JY, Seo JW, Du F, Varshavsky A. An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science. 2002;297:96–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YT, Kashina AS, Varshavsky A. Alternative splicing results in differential expression, activity, and localization of the two forms of arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase, a component of the N-end rule pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:182–93. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Tasaki T, Moroi K, An JY, Kimura S, Davydov IV, Kwon YT. RGS4 and RGS5 are in vivo substrates of the N-end rule pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507533102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoRusso SM, Rhee D, Sanger JM, Sanger JW. Premyofibrils in spreading adult cardiomyocytes in tissue culture: evidence for reexpression of the embryonic program for myofibrillogenesis in adult cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:183–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)37:3<183::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai W, Le Floc’h J, Vray D, Samarut J, Barthez P, Janier M. Evaluation of cardiovascular flow characteristics in the 129Sv mouse fetus using color-Doppler-guided spectral Doppler ultrasound. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:568–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AF, Phillips RM, Kumar A, Crawford K, Abbas Z, Lessard JL, de Tombe P, Solaro RJ. Ca2+ activation and tension cost in myofilaments from mouse hearts ectopically expressing enteric gamma -actin 10.1152/ajpheart.00890.2001. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H642–649. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00890.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Leddy JJ, Frank J, Holland P, Tuana BS. The association of cardiac dystrophin with myofibrils/Z-disc regions in cardiac muscle suggests a novel role in the contractile apparatus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12364–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otey CA, Kalnoski MH, Bulinski JC. Identification and quantification of actin isoforms in vertebrate cells and tissues. J Cell Biochem. 1987;34:113–24. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240340205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otey CA, Kalnoski MH, Bulinski JC. Immunolocalization of muscle and nonmuscle isoforms of actin in myogenic cells and adult skeletal muscle. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1988;9:337–48. doi: 10.1002/cm.970090406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otey CA, Kalnoski MH, Lessard JL, Bulinski JC. Immunolocalization of the gamma isoform of nonmuscle actin in cultured cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1726–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LR, Graceffa P, Dominguez R. The Crystal Structure of Uncomplexed Actin in the ADP State 10.1126/science.1059700. Science. 2001;293:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1059700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R, Kashina A. Identification of mammalian arginyltransferases that modify a specific subset of protein substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R, Mushegian A, Makarova K, Kashina A. Molecular dissection of arginyltransferases guided by similarity to bacterial peptidoglycan synthases. EMBO Reports. 2006;7:800–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee D, Sanger JM, Sanger JW. The premyofibril: evidence for its role in myofibrillogenesis. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1994;28:1–24. doi: 10.1002/cm.970280102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein PA, Spudich JA. Actin microheterogeneity in chick embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:120–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger JW, Ayoob JC, Chowrashi P, Zurawski D, Sanger JM. Assembly of myofibrils in cardiac muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;481:89–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4267-4_6. discussion 103–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger JW, Kang S, Siebrands CC, Freeman N, Du A, Wang J, Stout AL, Sanger JM. How to build a myofibril. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2005;26:343–54. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon D, Garner I, Buckingham M. Transcripts of alpha-cardiac and alpha-skeletal actins are early markers for myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Development. 1988;104:155–164. doi: 10.1242/dev.104.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soffer RL. The arginine transfer reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;155:228–40. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(68)90352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao K, Samejima K. Arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase activities in crude supernatants of rat tissues. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:1007–9. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullio AN, Accili D, Ferrans VJ, Yu ZX, Takeda K, Grinberg A, Westphal H, Preston YA, Adelstein RS. Nonmuscle myosin II-B is required for normal development of the mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12407–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove J, Weber K. At least six different actins are expressed in a higher mammal: an analysis based on the amino acid sequence of the amino-terminal tryptic peptide. J Mol Biol. 1978;126:783–802. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CCL, Xu T, Rai R, Bailey AO, Yates JR, Wolf YI, Zebroski H, Kashina A. Global Analysis of Posttranslational Protein Arginylation. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.