Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the cystectomy-induced damage on the follicular growth and ovulation of an affected ovary during natural cycles.

Methods

Twenty-eight infertile patients with unilateral ovarian endometriomas who underwent laparoscopic cystectomy were retrospectively evaluated. The ovulation rate of an affected ovary during natural cycles was compared before and after cystectomy in each patient, and it was also determined if ovulation from the affected ovaries resulted in pregnancy.

Results

After surgery, the ovulation rate was significantly lower than that before cystectomy (16.9 ± 4.5% vs. 34.4 ± 6.6%, P = 0.013). After surgery, 14 pregnancies were achieved without IVF treatment, and only 2 of them (14.3%) were achieved from an operated-side ovary. However, the pregnancy rate per ovulatory cycle of the operated-side ovary was not different from that of the intact ovary (8.8% vs. 5.8%, P = 0.750).

Conclusions

Laparoscopic cystectomy is an invasive treatment in that it reduces the frequency of ovulation; however the pregnancy rate per ovulation did not deteriorate.

Keywords: Endometrioma, Enucleation, Natural cycle, Ovarian reserve, Ovulation rate

Introduction

Widely varying figures for the prevalence of endometriosis have been published, and it is estimated that 3–10% of women of reproductive age and 25–35% of infertile women suffer from endometriosis, which is one of the leading causes of female infertility [1]. A recent review demonstrated that approximately 17–44% of women with endometriosis develop endometriomas [2–4], and the endometrioma itself may affect the outcome of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [5]. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometriomas is a favored treatment for the improvement of fecundity in infertile women with endometriosis [6, 7]. On the other hand, the presence of endometriosis without ovarian endometriomas may also affect the fecundity of infertile women [8, 9]. The impact of ovarian endometriomas on fecundity is a controversial issue [10]. Therefore, the management of an ovarian endometrioma before ART treatment is also controversial, especially for endometriomas with diameters greater than 3 cm [11].

Several surgical approaches for the treatment of endometriomas, such as aspiration, cystectomy, fenestration and ablation of the cyst wall, are performed worldwide, but currently there is no consensus on the most favorable approach with two aspects of preservation of ovarian reserve and subsequent improvement of ART outcome. Cystectomy is commonly performed on endometriomas more than 3 cm in diameter before ART treatment [12]. Some studies reported that endometrioma cystectomy had no detrimental effect on controlled ovarian hyperstimulation or on ART outcomes [13, 14], while some other studies reported that endometrioma cystectomy reduced response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation [15–18]. The authors report that reduced ovarian response and decreased ovarian reserve after cystectomy was directly affected by the surgery [15–17].

Most recently we reported that removal of endometriomas improved fecundity [19], and another report showed that, despite a reduction in ovarian reserve following laparoscopic cystectomy, pregnancy rate was unaffected [20]. In women who underwent unilateral cystectomy, the mean number of oocytes retrieved from the operated ovary was significantly less than that obtained from the contra-lateral, non-operated-ovary [21]. Most studies investigating the surgical adverse effect on the affected ovary evaluated ovarian response after stimulation in ART treatment, but there is no information concerning the frequency of ovulation from the affected ovary in non-stimulated cycles. In this study, the influence of laparoscopic cystectomy on follicle growth and ovulation in the affected ovary of unstimulated cycles was evaluated in infertile women with a unilateral endometrioma.

Materials and methods

Patients

From August 2002 to March 2007, 28 infertile patients who had a unilateral endometrioma were recruited for this study. All patients underwent laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy at the Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Perinatal Medicine and Maternal Care, National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo Japan. Patients with a history of gynecological operations, bilateral ovarian endometriomas, other ovarian mass, tubal obstruction and male infertility were excluded from this study. All patients showed regular menstrual cycles, and none of the women received exogenous gonadotropins or clomiphene citrate for ovarian stimulation during the studying period. All endometriomas were diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasound before surgery. The biaxial diameter of each endometrioma was measured by sonography and averaged as the size of the endometrioma. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Child Health and Development.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy was performed in our hospital as previously described [22]. In brief, all laparoscopic surgeries were performed under general anesthesia. A three-port laparoscopy was used with an umbilical 11 mm port for the scope and two additional 5 mm operating ports. A 10 mm laparoscope was inserted through an umbilical incision and connected to a video monitor (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Pneumoperitoneum was achieved (8 mmHg). Complete adhesiolysis and mobilization of the ovaries were performed, if necessary. An incision was made at the antimesentric site of the cysts. The cyst was dissected from the ovary by traction and countertraction with two atraumatic 5 mm grasping forceps. Bleeding from the stripped site was stopped by bipolar cauterization of the minimally required area for the shortest possible duration to avoid thermal damage to the ovarian cortex. None of the operated ovaries were sutured. The pelvic cavity was checked for the presence of peritubal- and pelvic-adhesions and endometriotic lesions, e.g., blue or red spots. Any other endometriotic deposits were ablated as much as possible. Adhesiolysis, electro-ablation, or resection of endometriotic lesions was performed to the extent that these procedures were possible. Tubal patency was checked with indigo carmine. Finally, the pelvic cavity was irrigated with a large amount of saline. Results of the examination of the pelvic cavity were recorded and scored according to the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis and the American Fertility Society classification of adnexal adhesions [23, 24]. After surgery all endometriomas were diagnosed by histological examination.

Confirmation of ovulation and ovulation rates

Before the laparoscopic surgery, ovulation and the ovulatory side of at least three cycles were checked for all patients. The ovulation was confirmed using the transvaginal ultrasound, urinary LH test (Do test LH, Rohto Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka) and basal body temperature. Transvaginal ultrasonography Mochida Sonovista-Color II (Mochida, Tokyo, Japan) with either a 6.0 MHz transvaginal probe or a GE LOGIQ 3 (GE Yokokawa, Tokyo, Japan) with a 6.0 MHz transvaginal probe was performed in all patients 3 days before and after the follicular rupture. At least one scan was performed within 48 h of the rupture of the leading follicle. In addition to the follicular rupture, either the presence of a corpus luteum, a clouded endometrium, or fluid in the Douglas pouch was used as ultrasound criteria for presuming ovulation.

The frequency of ovulation from the affected ovary was defined as the ovulation rate. The ovulation rate was calculated for each patient as follows: the number of ovulatory cycles from an affected ovary was divided by the total number of ovulatory cycles, and the mean ovulation rate per patient was derived. The ovulation rate was compared retrospectively before and after surgery, and this rate was also compared according to the size of the endometrioma.

Clinical pregnancy was confirmed by the presence of a gestational sac with transvaginal ultrasound, and it was determined if ovulation from the diseased ovaries resulted in pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank, Mann-Whitney U, and Chi-square tests. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The characteristics of patients who underwent laparoscopic cystectomy are summarized in Table 1. The mean age and duration of infertility were 33.4 ± 0.6 years old and 5.4 ± 0.8 years, respectively. The mean endometrial cyst diameter and r-ASRM score were 4.1 ± 0.4 cm and 31.0 ± 1.9 points, respectively. The mean adnexal adhesion score of affected-side and intact-side were 3.0 ± 0.5 points (range, 0–10 points) and 1.2 ± 0.6 (range, 0–14 points) respectively, and there was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). The mean period of follow-up time (months) per patient between pre-surgery and that of post-surgery was not different (3.9 ± 0.6 vs. 6.8 ± 1.2, P = 0.07). In 28 patients, a total of 109 ovulatory cycles were confirmed before surgery, and 190 cycles were confirmed after surgery. All observational cycles were unstimulated, and there was no cycle in which two or more follicles grew and ovulated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who underwent laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy

| Number of patients | 28 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.4 ± 0.6 | 28–38 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 1–16 |

| Diameter of endometrioma (cm) | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5–6.6 |

| r-ASRM score (points) | 31.0 ± 1.9 | 18–36 |

| Adnexal adhesion score (points; affected-side) | 3.0 ± 0.5* | |

| (Points; intact-side) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | |

| Follow-up period (months; pre-surgery) | 3.9 ± 0.6** | |

| (Months; post-surgery) | 6.8 ± 1.2 |

Mann-Whitney U test was used. Values are mean ± S.E.M.

*P < 0.001 vs. adnexal adhesion score of intact-side ovary

**P = 0.07 vs. follow-up period of post-surgery

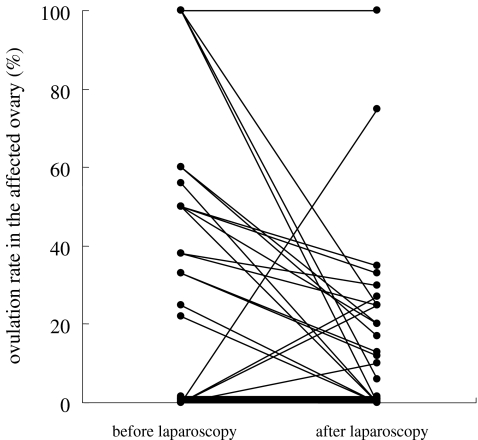

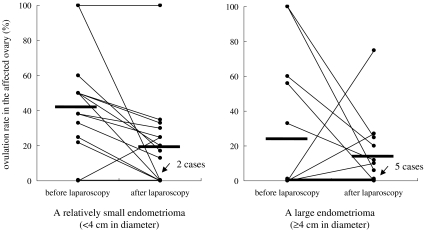

The ovulation rate after surgery was 16.9 ± 4.5%, which was significantly lower than that before surgery (34.4 ± 6.6%, P = 0.013, Table 2, Fig. 1). Fifteen of the 28 patients had a relatively small endometrioma (<4 cm in diameter) and the ovulation rate after surgery (19.8 ± 6.7%) was significantly lower than that before surgery (41.0 ± 8.0%, P = 0.010, Table 2, Fig. 2). By contrast, in the other 13 women who had a large endometrioma (≥4 cm in diameter), the ovulation rate after surgery (13.5 ± 5.8%) was comparable to that before surgery (26.8 ± 10.9%, P = 0.330, Table 2, Fig. 2). Before surgery the ovulation rate in the patients with a small (<4 cm) endometrioma was not significantly different from that in the patients with a large (≥4 cm) endometrioma (41.0 ± 8.0% vs. 26.8 ± 10.9%, P = 0.197), and the ovulation rate after surgery was similar in both groups (19.8 ± 6.7% vs. 13.5 ± 5.8%, P = 0.399).

Table 2.

Effects of endometrioma size on ovulation rate of the affected ovary before and after laparoscopic cystectomy

| Ovulation rate (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before surgery | After surgery | ||

| Total | 34.4 ± 6.6% | 16.9 ± 4.5% | 0.013 |

| A relatively small endometrioma (n = 15, <4 cm in diameter) | 41.0 ± 8.0% | 19.8 ± 6.7% | 0.010 |

| A relatively large endometrioma (n = 13, ≥4 cm in diameter) | 26.8 ± 10.9% | 13.5 ± 5.8% | 0.330 |

Values are mean ± S.E.M. All observational cycles were unstimulated, and there was no cycle in which two or more follicles grew and ovulated. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used

Fig. 1.

Changes of ovulation rates in the affected ovary in each patient. The ovulation rate in the affected ovary before and after laparoscopic cystectomy in each patient was measured. The ovulation rate in the affected ovary after laparoscopic surgery was 16.9 ± 4.5% (mean ± S.E.M.), which was significantly lower than the rate before laparoscopic surgery (34.4 ± 6.6%, P = 0.013). The bars represent the mean ovulation rates. Data were statistically analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test

Fig. 2.

Effects of endometrioma size on ovulation rate. Out of 28 patients, 15 had a relatively small endometrioma (<4 cm in diameter), and, for this group, the ovulation rate after laparoscopic surgery (19.8 ± 6.7%) was significantly lower than the rate before laparoscopic surgery (41.0 ± 8.0%, P = 0.010). On the other hand, for the other 13 patients who had a large endometrioma (≥4 cm in diameter), there was no statistically significant difference in ovulation rates before (26.8 ± 10.9%, P = 0.330) and after laparoscopic surgery (13.5 ± 5.8%). The bars represent the mean of ovulation rates. Data were statistically analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test

After surgery, 14 of 28 patients (50%) achieved pregnancy without IVF treatment; 12 resulted from timed intercourse and 2 resulted from intrauterine insemination. Only 2 of these 14 (14.3%) pregnancies occurred in the cycles ovulated from the operated side. After surgery, 156 of 190 ovulatory cycles occurred in the intact-side ovary, and 12 pregnancies were achieved (pregnancy rate per ovulatory cycles = 5.8%). In the other 34 cycles, ovulation occurred in the operated-side ovary, and 2 pregnancies were achieved (pregnancy rate per ovulatory cycles = 8.8%) this rate did not differ from that occurred in intact-side ovaries (P = 0.750, Table 3).

Table 3.

Pregnancy rate per ovulation cycle of the operated- and intact-side ovaries after cystectomy

| Operated-side | Intact-side | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy cycles/ovulation cycles | 2/34 | 12/156 | |

| (%) | (8.8) | (5.8) | 0.750 |

All observational cycles were unstimulated, and there was no cycle in which two or more follicles grew and ovulated. There was no statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate per ovulation cycle between operated- and intact-side ovaries (P = 0.750). Data were statistically analyzed using the Chi-square test

Discussion

There is some evidence that excisional surgery for endometriomas provides for a more favorable outcome than drainage and ablation, with regard to the recurrence of the endometrioma, recurrence of symptoms and subsequent spontaneous pregnancy in women who were previously subfertile [10]. However, the indication for a surgical approach to the management of small asymptomatic ovarian endometrioma in the subfertile patient is controversial. Therefore, management of ovarian endometriomas remains to be a daunting task for many clinicians.

Many previous reports have demonstrated that the presence of an ovarian endometrioma impairs the quality of oocytes, as revealed by reduced rates of fertilization and implantation [5, 25, 26]. Since an ovarian endometrioma itself reduces fecundity in infertile patients, the removal of it might be an optimal treatment. Indeed, our recent report indicated that laparoscopic removal of an ovarian endometrioma had significant benefits for infertile patients, including an improved pregnancy outcome [19].

Recent evidence suggests that laparoscopic cystectomy of an ovarian endometrioma reduces ovarian reserve and consequently the response to ovarian stimulation [12, 15–18]. Most of these reports compared the adverse effects of cystectomy on subsequent response to IVF treatments, such as the response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and the mean number of oocytes retrieved in operated versus non-operated patients [21, 27–29], but there were few reports studying the effect of the presence of endometrioma and cystectomy on ovulation and the adverse effect of cystectomy in unstimulated cycles. In this study, to evaluate surgically adverse effects in the affected ovary we investigated the frequency of ovulation from the affected ovaries, using a within-subject design, before and after laparoscopic cystectomy. This study has some meaningful results of clinical significance. First, a change of the ovulation rate in each patient was continuously observed before and after surgery in non-stimulated cycles. Second, laparoscopic cystectomy of an endometrioma was an invasive treatment in terms of the frequency of ovulation, because the ovulation rate in the diseased ovary was significantly decreased after surgery, particularly in patients with small endometriomas (<4 cm). But, there was no significant change in ovulation rate among patients with relatively large endometriomas (≥4 cm) before and after surgery, because follicular growth and ovulation had been already impaired by the presence of the large endometrioma. Therefore, laparoscopic cystectomy might not have an additional negative effect on ovulation in patients having relatively large endometrioma. As regards the surgically adverse effects, our results were comparable to previous reports investigating ovarian response to stimulation [21, 27–29]. Particularly in patients with a small (<4 cm) endometrioma, laparoscopic cystectomy should not be performed to preserve ovarian reserve in terms of ovulation rate.

It is generally assumed that the frequency of ovulation occurred equally in each ovary with same ovarian reserve [30]. But, in this study the ovulation rate in the affected ovary before surgery was 34.4%, and this figure is the mean of the ovulation rate in each patient. If the frequency of ovulation were equal between the intact and the affected ovaries, this figure would be statistically lower than the theoretical frequency (50%) (Chi square test, P < 0.05). Thus, the ovulation rate of the affected ovary was already decreased before surgery; an endometrioma itself might cause this impairment. However, before surgery there was no statistical difference between the ovulation rate of small and large endometriomas, ovulation rate tended to decrease more in a large endometrioma. A large endometrioma might cause more impairment. Further studies with larger numbers of patients are needed.

Recently, Esinler et al. showed that patients with an endometrioma who were confirmed to have intact fallopian tubes and tubal patency, especially in intact ovaries, had higher pregnancy rates after laparoscopic surgery [12]. In fact, after laparoscopy, 50% of infertile patients achieved pregnancy by timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination without IVF treatment in this study. Although there were more adhesive findings in affected-side adnexa, there was no significant difference in the rate of pregnancy per ovulation cycle between the operated- and intact-side ovaries after surgery. This result indicated that the quality of oocytes did not deteriorate during folliculogenesis after laparoscopic cystectomy. This is an advantageous aspect about laparoscopic surgery. But further studies with a larger number of patients are needed.

Conclusions

In this study, we were able to clarify the surgically adverse effects on ovarian reserve by assessing a change of the frequency of ovulation from affected ovaries during the natural cycle of patients with unilateral endometriomas before and after surgery. This study demonstrated that the presence of an endometrioma already reduced the frequency of ovulation and laparoscopic cystectomy caused a reduction of the ovarian reserve, as evidenced by the reduced ovulation rate of the affected ovary after surgery. However, half of the patients who underwent laparoscopic cystectomy achieved pregnancy without IVF in spite of some disadvantageous influences. According to these results, laparoscopic cystectomy reduces the frequency of ovulation in the operated ovary, but maintains the pregnancy rate per ovulation. In terms of preserving ovarian reserve, it is recommended that laparoscopic cystectomy should be performed for infertile patients with a large (≥4 cm) endometrioma. However, for patients with a small (<4 cm) endometrioma you should exercise great care in deciding whether or not to perform cystectomy.

Footnotes

Capsule

The frequency of ovulation in an affected ovary was significantly reduced after laparoscopic endometriomal cystectomy; however, the pregnancy rate per ovulation was unaffected by cystectomy.

References

- 1.Speroff LGR, Kase NG, editors. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- 2.Busacca M, Vignali M. Ovarian endometriosis: from pathogenesis to surgical treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2003;15:321–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jenkins S, Olive DL, Haney AF. Endometriosis: pathogenetic implications of the anatomic distribution. Obstet Gynecol 1986;67:335–8. [PubMed]

- 4.Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril 1999;72:310–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Yanushpolsky EH, Best CL, Jackson KV, Clarke RN, Barbieri RL, Hornstein MD. Effects of endometriomas on ooccyte quality, embryo quality, and pregnancy rates in in vitro fertilization cycles: a prospective, case-controlled study. J Assist Reprod Genet 1998;15:193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yoshida S, Harada T, Iwabe T, Terakawa N. Laparoscopic surgery for the management of ovarian endometrioma. Gynecol Obstet Investig 2002;54 Suppl 1:24–7. discussion 27–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2005: CD004992. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004992.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Harada T, Iwabe T, Terakawa N. Role of cytokines in endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2001;76:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Yoshida S, Harada T, Iwabe T, Taniguchi F, Mitsunari M, Yamauchi N, et al. A combination of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor impairs sperm motility: implications in infertility associated with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2004;19:1821–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Isaacs JD Jr, Hines RS, Sopelak VM, Cowan BD. Ovarian endometriomas do not adversely affect pregnancy success following treatment with in vitro fertilization. J Assist Reprod Genet 1997;14:551–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chapron C, Vercellini P, Barakat H, Vieira M, Dubuisson JB. Management of ovarian endometriomas. Hum Reprod Updat 2002;8:591–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Esinler I, Bozdag G, Aybar F, Bayar U, Yarali H. Outcome of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection after laparoscopic cystectomy for endometriomas. Fertil Steril 2006;85:1730–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril 1998;70:1176–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Canis M, Mage G, Wattiez A, Pouly JL, Bruhat MA. The ovarian endometrioma: why is it so poorly managed? Laparoscopic treatment of large ovarian endometrioma: why such a long learning curve? Hum Reprod 2003;18:5–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marconi G, Vilela M, Quintana R, Sueldo C. Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy of endometriomas does not affect the ovarian response to gonadotropin stimulation. Fertil Steril 2002;78:876–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ho HY, Lee RK, Hwu YM, Lin MH, Su JT, Tsai YC. Poor response of ovaries with endometrioma previously treated with cystectomy to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J Assist Reprod Genet 2002;19:507–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Somigliana E, Ragni G, Benedetti F, Borroni R, Vegetti W, Crosignani PG. Does laparoscopic excision of endometriotic ovarian cysts significantly affect ovarian reserve? Insights from IVF cycles. Hum Reprod 2003;18:2450–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Suganuma N, Wakahara Y, Ishida D, Asano M, Kitagawa T, Katsumata Y, et al. Pretreatment for ovarian endometrial cyst before in vitro fertilization. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2002;54 Suppl 1:36–40. discussion 41–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Nakagawa K, Ohgi S, Kojima R, Sugawara K, Ito M, Horikawa T, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on fecundity of infertility patients with ovarian endometrioma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2007;33:671–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Loo TC, Lin MY, Chen SH, Chung MT, Tang HH, Lin LY, et al. Endometrioma undergoing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy: its influence on the outcome of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET). J Assist Reprod Genet 2005;22:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Loh FH, Tan AT, Kumar J, Ng SC. Ovarian response after laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometriotic cysts in 132 monitored cycles. Fertil Steril 1999;72:316–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Nakagawa K, Ohgi S, Horikawa T, Kojima R, Ito M, Saito H. Laparoscopy should be strongly considered for women with unexplained infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2007;33:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril 1988;49:944–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril 1997;67:817–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Cahill DJ, Wardle PG, Maile LA, Harlow CR, Hull MG. Ovarian dysfunction in endometriosis-associated and unexplained infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet 1997;14:554–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Pal L, Shifren JL, Isaacson KB, Chang Y, Leykin L, Toth TL. Impact of varying stages of endometriosis on the outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet 1998;15:27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Donnez J, Wyns C, Nisolle M. Does ovarian surgery for endometriomas impair the ovarian response to gonadotropin? Fertil Steril 2001;76:662–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Somigliana E, Infantino M, Benedetti F, Arnoldi M, Calanna G, Ragni G. The presence of ovarian endometriomas is associated with a reduced responsiveness to gonadotropins. Fertil Steril 2006;86:192–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ragni G, Somigliana E, Benedetti F, Paffoni A, Vegetti W, Restelli L, et al. Damage to ovarian reserve associated with laparoscopic excision of endometriomas: a quantitative rather than a qualitative injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:1908–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Balasch J, Penarrubia J, Marquez M, Mirkin SR, Carmona F, Barri PN, et al. Ovulation side and ovarian cancer. Gynecol Endocrinol 1994;8:51–4. [DOI] [PubMed]