Abstract

We propose that there is an opportunity to devise new cancer therapies based on the recognition that tumors have properties of ecological systems. Traditionally, localized treatment has targeted the cancer cells directly by removing them (surgery) or killing them (chemotherapy and radiation). These modes of therapy have not always been effective because many tumors recur after these therapies, either because not all of the cells are killed (local recurrence) or because the cancer cells had already escaped the primary tumor environment (distant recurrence). There has been an increasing recognition that the tumor microenvironment contains host noncancer cells in addition to cancer cells, interacting in a dynamic fashion over time. The cancer cells compete and/or cooperate with nontumor cells, and the cancer cells may compete and/or cooperate with each other. It has been demonstrated that these interactions can alter the genotype and phenotype of the host cells as well as the cancer cells. The interaction of these cancer and host cells to remodel the normal host organ microenvironment may best be conceptualized as an evolving ecosystem. In classic terms, an ecosystem describes the physical and biological components of an environment in relation to each other as a unit. Here, we review some properties of tumor microenvironments and ecological systems and indicate similarities between them. We propose that describing tumors as ecological systems defines new opportunities for novel cancer therapies and use the development of prostate cancer metastases as an example. We refer to this as “ecological therapy” for cancer.

Tumors as Ecological Systems

Since the work of Cairns and Nowell in the 1970s, cancer has been described as a process that can be understood in terms of darwinian evolution [1–4]. Tumor cell heterogeneity is the result of competition between various clones of cancer cells that act as competing species for resources in the tumor microenvironment [2–6]. It is generally accepted that cancers evolve by darwinian principles (Figure 1) [5–9]. These principles include clonal proliferation, mutational and epigenetic changes within the clonal population resulting in genetic diversity, and selection pressures such as lack of nutrients leading to proliferation of subclones [5–9]. This knowledge, however, has not resulted in changes in treatment paradigms for cancer therapy. Placing cancer cell clonal evolution within the context of its environment provides a novel paradigm that can lead to new therapeutic interventions.

Figure 1.

Darwinian evolution and cancer. Cancers evolve by darwinian principles that include clonal proliferation, mutational changes within the clonal population resulting in genetic diversity, and selection pressures leading to proliferation of subclones that bridge bottlenecks such as lack of nutrients and space limitations. (A) In the traditional view of tumor progression, there is competition between genetically unstable, partially transformed, proliferating cells. The cells compete for limited oxygen, essential nutrients, and growth factors, and therefore, many die. Eventually, one cell accumulates sufficient mutations to express all of the functions required for a clone of fully malignant cells to emerge as a successful species occupying an environmental niche. This founder cell can be the result of selective pressures as indicated by the bottlenecks or the result of intrinsic genetic instability leading to a full complement of mutations that are required for full malignant potential. The bottlenecks indicate where a new dominant cell type becomes apparent. (B) In addition, we have hypothesized a tumor progression model based on the theory of cooperation. Genetically unstable partially transformed cells proliferate and yield different mutant cell types. The different cell types cooperate with each other, enabling them to survive and proliferate. The concept of cooperation among partially transformed cells is added to the traditional view of tumor progression. As in the traditional view, eventually one cell may accumulate sufficient mutations to express all of the functions required for a clone of fully malignant cells to emerge as the dominant species. Adapted from (A) Greaves [6] and Axelrod et al. [5].

Cancer has been considered as an emergent property of a complex adaptive system [10–12]. Similarly, the emergent property of a classic ecosystem is the collective behavior of its constituent parts. In the 1930s, the term ecosystem was coined by Clapham and then popularized and put into print by Tansley to describe the physical and biological components of an environment considered in relation to each other as a unit [13]. In the 1950s, Odum et al. [14] popularized the concept of ecosystems as interactive systems established between a group of living creatures and their biotope (the nonliving components of the environment). Although they may be bounded and individually discussed, ecosystems do not exist independently but interact in a complex web of ecological relationships connecting all ecosystems to make up the biosphere (earth as a whole). The emergent properties of ecosystems are the consequence of the interactions of a diverse mixture of different organisms with each other and with their nonbiological environment. The organisms in ecosystems are characterized by the numbers of each type of organism, their spatial and temporal organization, and their interactions with each other and with their physical and chemical environments [13,14]. Organisms communicate with other similar and different kinds of organisms. Communication and feedback between organisms may be negative or positive [15]. Organisms compete for limited resources and cooperate for mutual advantage. Ecosystems are dynamic. The numbers and kinds of organisms may fluctuate with time. Predation may reduce the number of some organisms and increase the number of others. Organisms with low numbers may become extinct. Open systems may change over time with immigration or emigration, and closed systems may change as resources become limiting. Reproduction of organisms has consequences described by evolutionary considerations of variation, inheritance, and selection over time [16–19].

The cancer and host cells in the tumor microenvironment interact similarly to organisms in an ecological community. There are different kinds of cells within a tumor and its adjacent region, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), cancer-associated fibroblasts, myoepithelial cells, and other cells of the host stroma [20–27]. Cells associated with the tumor may have characteristic spatial organization, such as host-infiltrating macrophages and angiogenic endothelial cells within the mass of cancer cells, or myoepithelial and stromal cells external to the cancer mass. The spatial organization of the tumor, i.e., tumor morphology, is influenced by selective pressure from the microenvironment [28]. Communication between tumor cells and between tumor and host cells occurs through direct physical interactions and paracrine signaling [29–34]. Tumors, like classic ecosystems, are dynamic, and the kinds of cells and the number of cells change with time. For instance, an increase in the number of cells with constitutively up-regulated aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) [35]. In the evolutionary context, cancer cells and host cells accumulate mutations by selection or genetic drift [3,36–39]. Together, the cancer cells and host cells, interacting within their habitat, create an ecosystem. This ecosystem, in turn, exists within a larger environment or biosphere (the host patient).

Opportunities for Ecological Therapy for Cancer

The similarity of classic ecological systems and tumors suggests, by analogy, that some features of ecological systems could be exploited for cancer therapy. A species within an ecosystem can be destroyed by directly killing the species itself, e.g., the extinction of the dodo bird on Mauritius in the 16th and 17th centuries [40]. Within the paradigm of contemporary cancer therapy, this is exemplified by chemotherapy and targeted agents [41–43]. In general, this is an inefficient approach and, except for a few notable exceptions, has rarely resulted in curative cancer treatment [44]. Within the context of darwinian evolution, often the most efficient way to kill a species is to destroy its niche by altering the environment. Ecological systems exist as a network of dependencies. In a simple example, it is much easier to drain a swamp than it is to individually swat all of the mosquitoes living there. This approach, however, also kills all of the other species living in the swamp. The challenge in patients with cancer is to identify nonessential elements of the environment that are promoting the growth of the cancer cells and to eliminate them. These nonessential elements may be host cells that may be attracted to the tumor site and not normal components of that microenvironment or they may be normal host cells that have been altered by their ongoing interactions with the cancer cells. Another way to change the dynamic interactions of the ecosystem is to alter the microenvironment in such a way that is harmful to the cancer cells but does not cause long-term detriment of the patient. For example, it has been long recognized that heat is an important microenvironmental and epigenetic factor in biological development [44,45]. In many tumor types, hyperthermia (41–43°C) increases and synergizes the therapeutic response to radiation, cytotoxic drugs, and immunotherapy [44–46]. As noted by Coffey et al. [44], hyperthermia has not been widely accepted because of limitations in clinical application and understanding. With new types of thermal delivery systems, however, it is now possible to more precisely target cancer cells with specific tumor cell hyperthermia and alter the local ecology of the tumor microenvironment to enhance the effects of radiation and chemotherapy [44,47–49]. This approach has been termed temperature-enhanced metastatic therapy (R.H. Getzenberg, Johns Hopkins University). It should be noted that ecosystems, by definition, are adaptive. In this instance, if the cancer cells are not eliminated by thermally enhanced therapy, thermotolerant subclones of cancer and host cells may be selected, and the ecosystem will dynamically reorganize to a new state.

As noted, another way to alter the ecosystem is to kill other species within the environment that are supporting the growth and survival of the species of interest. One of the features of classic ecosystems is the interdependence of different types of organisms on each other. Some organisms may be dependent on others for survival, such as parasitism to the benefit of one to the detriment of the other or commensalism in which there is a benefit of one without harm to the other. Another example of biological interaction between species is mutualism or symbiosis, where both species benefit from interacting with each other. The implications for cancer therapy for commensalism and mutualism are that targeting noncancer cells, from which the cancer cells are receiving benefit, should also reduce the number of tumor cells. Examples of noncancer cells that cancer cells depend on/receive benefit from include endothelial cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and TAMs.

Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis as an Example of a Tumor Ecosystem

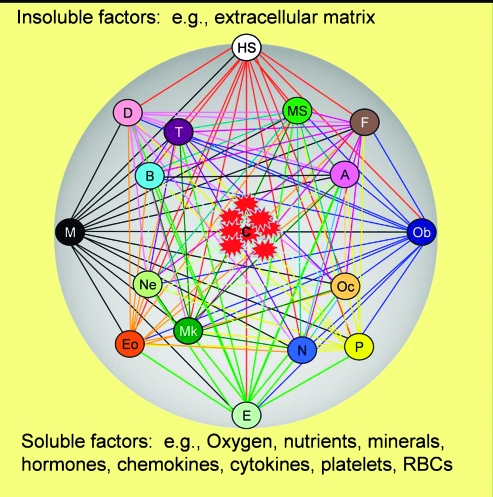

Prostate cancer provides an example to apply the potential of ecological therapy. In prostate cancer, cells metastasize to the bone by parasitizing the hematopoietic stem cell niche [50,51]. We have previously described this process in a series of steps involving emigration from the primary prostate tumor, migration through the lymphatics and blood stream, immigration to the metastatic site, and naturalization of the bone marrow as the cancer cells establish themselves and proliferate. We continue to hypothesize that the cancer cells may cooperate with each other and with host cells to share resources and provide each other with growth and survival factors to successfully create a new ecosystem in the bone microenvironment [5,15,50,51]. Prostate cancer cells in a bone metastasis ecosystem are in close proximity, or contact, and communicate with multiple kinds of host cells. Each group of cells of similar morphology and function can be considered as a separate species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The prostate cancer bone metastasis ecosystem. Prostate cancer cells (C) in the bone metastasis ecosystem are in close proximity and/or contact with a variety of cell types, each of which can be considered a species based on their similarities in morphology and function. These cell types include hematopoietic stem cells (HS), mesenchymal stem cells (MS), endothelial cells (E), pericytes (P), fibroblasts (F), macrophages (M), T lymphocytes (T), B lymphocytes (B), dendritic cells (D), adipocytes (A), neurons (N), osteoclasts (Oc), osteoblasts (Ob), megakaryocytes (Mk), neutrophils (Ne), and eosinophils (Eo). All of these cell species are interacting with the soluble and insoluble factors that make up the biotope of the bone microenvironment. Insoluble factors include the collagen and pyrophosphate of the bone extracellular matrix. Soluble factors include those supplied by host biosphere through the blood stream, e.g., oxygen, trace elements, and hormones, and those produced locally, e.g., chemokines and cytokines. The lines connecting cell types suggest possible interactions.

These cells include hematopoietic stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, adipocytes, neurons, osteoclasts, osteoblasts, megakaryocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. All of these cell species are interacting with the soluble and insoluble factors that make up the nonliving components (biotope) of the bone microenvironment [14]. Insoluble factors include the collagen and pyrophosphate of the bone extracellular matrix. Soluble factors include those supplied by host biosphere through the blood stream, e.g., oxygen, nutrients, trace elements, and hormones, and those produced locally, e.g., chemokines and cytokines. Although all of these components are interacting in a dynamic fashion, the ecosystem paradigm provides a conceptual framework to understand these interactions and defines therapeutic interventions based on them. For example, because many of these cells are providing the cancer cells with factors that promote growth and survival, inhibiting their function will in turn, inhibit cancer cell proliferation.

Using the Ecosystem Paradigm to Identify Possible Therapies: The Case of Metastatic Prostate Cancer

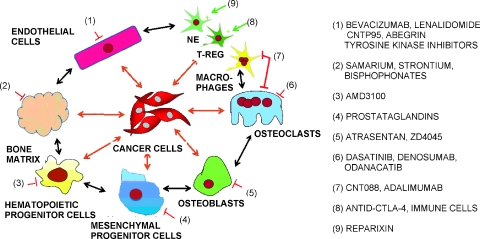

Bone metastases from prostate cancer kill 28,000 men in the United States each year [52]. Once prostate cancer cells travel to a bone marrow site and begin to naturalize, they create a tumor ecosystem that is fundamentally different from normal bone marrow. The interaction of cancer cells with the bone microenvironment results in a vicious cycle in which tumor cells cooperate with both host osteoclasts and osteoblasts to exacerbate bone destruction and increase cancer cell growth [53–56]. Targeting the various elements of this vicious cycle provides an example of ecological therapy (Table 1 and Figure 3). The normal host cells that are participating in the tumor ecosystem of a bone metastasis are functioning inappropriately. Therefore, they represent viable targets for therapy that should not harm the normal bone microenvironment of the patient.

Table 1.

Targeting the Noncancer Cell Species in the Prostate Cancer Metastasis Ecosystem with Therapeutic Intent.

| Cell Type | Target | Example Agents | References |

| Endothelial cells | VEGF | Bevacizumab | [57] |

| VEGF receptor | Sunitinib, sorafenib | [58,59] | |

| αv Integrins | CNTO95, Vitaxin | [60] | |

| Osteoblasts | Endothelin-1 | Atrasentan, ZD-4054 | [61,62] |

| IL-6 | CNTO328 | [63,64] | |

| Osteoclasts | RANKL | Denosumab | [65] |

| Maturation | Bisphosphonates | [66,67] | |

| src | Dasatanib | [68] | |

| Cathepsin K | Odanacatib | [69] | |

| Fibroblasts | TGFβ | Lerdelimumab, SB431542 | [70–73] |

| Mesenchymal progenitor cells | Prostaglandins | COX-2 inhibitors | [76,77] |

| Hematopoietic progenitor cells | CXCL12 | Sitagliptin, AMD3100 | [79–82] |

| Annexin II | Interferon gamma | [83] | |

| Eosinophils | Eotaxin (CCL11) | Heparin, prednisolone | [84,85] |

| Neutrophils | CXCR1/CXCR2 | Reparixin | [86] |

| T cells | CTLA-4 | Ipilimumab | [87,88] |

| Macrophages | CCL2 | CNTO888 | [95,96] |

| CCR2 | Adalimumab | [97] |

Figure 3.

Targeting the prostate cancer metastasis ecosystem for cancer therapy. The ecosystem of prostate cancer bone metastases presents several targets for cancer therapy that are currently being studied in the preclinical and clinical settings. Agents to inhibit osteoclast maturation and function (bisphosphonates) as well as endothelial cell proliferation (bevacizumab) are already in clinical use. Agents that inhibit osteoblast function are in clinical trial. Agents that modulate the cells of the immune system hold promise and are being studied preclinically as well as clinically. The recognition that cancer cells interact with mesenchymal and hematopoietic stem cells has opened new avenues of investigation for the treatment of bone metastases.

All cells within the bone tumor ecosystem, including the prostate cancer cells, require a constant supply of nutrients from the blood stream. A proliferating tumor mass requires new blood vessels to sprout and proliferate (neoangiogenesis). In this setting, new blood vessel growth is not required by the body, and therefore, neoangiogenesis has been recognized as an ideal target for cancer therapy. Strategies that block neoangiogenesis by inhibiting different targets are in development. These include a current phase 3 trial of the combination of the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody bevacizumab with the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel in men with advanced prostate cancer [57]. The interaction of VEGF with its receptors can also be blocked with antibodies that bind to the VEGF receptors or with kinase inhibitors, many of which are in phase 2 trials [58,59]. Another strategy blocks the sprouting of blood vessels into the extracellular matrix through inhibition of integrin binding, consequently, restricting tumor growth [60].

In bone metastases, bone metabolism has been deregulated, and the cells that mediate bone turnover, osteoblast and osteoclasts, are inappropriately turned on. This provides another ideal target for therapy as there is very little bone remodeling in the normal adult. Much attention, therefore, has been focused on interrupting the osteoblast-osteoclast axis in bone metastases. Endothelin-1 is a mediator of growth and function for osteoblasts, and inhibition of its receptor continues to be of major interest to the prostate cancer community [61,62]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is produced by osteoblasts and serves as a potent survival cytokine for cancer cells and multiple host cells. Interruption of IL-6 has been demonstrated to have profound effects on the tumor ecosystem, including inhibiting osteoclast maturation and function, enhancing chemotherapy efficacy, and decreasing macrophage survival [63,64]. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts directly communicate through the osteoprotegerin receptor-receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) axis, which mediates maturation of the osteoclasts [65]. This axis is inhibited by denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL. Osteoclast maturation and function can also be inhibited by the bisphosphonates, which bind to exposed bone matrix and directly poison the osteoclasts, by dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the src pathway, and by odanacatib, a cathepsin K inhibitor that blocks enzyme degradation of the bone [66–69]. The bisphosphonates are in widespread clinical use as adjuncts to chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. Interrupting the bone remodeling axis is an example of therapy that inhibits host cells that are providing essential factors to the tumor cells, i.e., interrupting the ecologic network of dependencies.

While agents that inhibit endothelial cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts have all been put to clinical use, the bone metastasis ecosystem paradigm identifies several new targets for cancer therapy. Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) is a powerful regulator of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [70–73]. Transforming growth factor beta mediates interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment. For example, the loss of TGFβ signaling in fibroblasts results in a protumorigenic microenvironment that supports the transformation of adjacent epithelial cells [73]. The inhibition of TGFβ signaling is being explored with several small molecule and antibody inhibitors [70]. Mesenchymal stem cells have been proposed as the center of a bone metabolic unit that regulates bone homeostasis and the bone microenvironment [74–77]. Mesenchymal stem cells are a pluripotent cell type that can differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and other cells and, therefore, play a major supportive role in the prostate cancer metastasis ecosystem. Potential methods to clinically inhibit mesenchymal stem cells are largely unexplored. We propose, however, that prostaglandin inhibitors, e.g., COX-2 pathway, may be able to affect the function of these cells within the context of tumors [74,75]. Hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells (HSCs) are another major component of the bone tumor microenvironment. The realization of the importance of the HSC niche in the process of metastasis has been growing with the discovery that metastasizing cancer cells use many of the same mechanisms and properties of HSCs to establish themselves in the bone [51,78]. It seems that cancer cells and HSCs compete for similar binding sites on osteoblasts [78]. Agents that act to mobilize HSC and/or cancer cells out of the bone marrow microenvironment, or prevent them from binding in the endosteal niche, may be valuable additions to ecological therapy against bone metastases [79–83].

Another major component of the bone metastasis ecosystem consists of cells of the immune system. Modulators of these cells, many in development for inflammatory diseases, have been largely unexplored in cancer therapy. Eosinophils may be targeted by inhibiting eotaxin through heparin analogs or steroids [84,85]. Neutrophil recruitment may be inhibited by blocking CXCR1/CXCR2-mediated chemotaxis [86]. FoxP3 (+) regulatory T cells (Tregs) are necessary for control of deleterious immune responses [87]. Tregs have been demonstrated to have antitumor activity through a variety of immunomodulatory mechanisms. CTLA4 negatively regulates steady-state Treg homeostasis, and inhibition of CTLA4 has been demonstrated to have an anticancer activity by increasing the Treg presence and function at tumor sites [87,88].

One of the best examples of cooperation among cell types within the tumor microenvironment is the relationship between cancer cells and TAMs [89–91]. Tumor-associated macrophages and cancer cells cooperate with each other in the tumor ecosystem in a symbiotic relationship that promotes the proliferation and growth of each other. Tumor-associated macrophages are a rich source of growth factors, e.g., VEGF, promoting blood vessel growth to the tumor, and epidermal growth factor, promoting cancer cell proliferation [92–94]. In turn, cancer cells provide soluble factors to promote survival of the TAMs, e.g., IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1, CCL2) [95]. Because TAMs are not a part of the normal bone microenvironment, they can be treated as an invasive species to the ecosystem. We, and others, have demonstrated that inhibition of TAM infiltration into the tumor microenvironment by blocking CCL2-mediated chemoattraction is a potent suppressor of tumor growth in preclinical models [95,96]. Interruption of this pathway is an area of active clinical investigation [95–97].

Conclusion

Initially, an expanding population of cancer cells, whether they are at the primary site or at a metastatic site, exists as an invasive species of a particular organ ecosystem. As the cancer cells proliferate, they become the dominant species and naturalize the environment to create a tumor ecosystem that is not only based on the properties of the tumor cells but also defined by the cell types and biotope of that particular organ [3]. By recognizing that tumors have similarities to classic ecosystems, we have extended the concept of the tumor microenvironment. The ecosystem framework reminds us that tumors are dynamic evolving systems that involve not only the cancer cells changing with time, but the host components as well. This strategy suggests multitargeted therapeutic approaches based on defining the unique elements of the ecological niche created by tumor-host interactions. We have termed this strategy ecological therapy for cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rhonda Hotchkin for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

K.J. Pienta is supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA093900, an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship, NIH Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in prostate cancer grant P50 CA69568, Cancer Center support grant P30 CA 46592, SouthWest Oncology Group grant CA32102, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a Ralph Wilson Medical Research Foundation grant, and a Wallace H. Coulter Foundation Translational Partners Seed grant. R. Axelrod is supported by the University of Michigan's LS&A Enrichment Fund. D.E. Axelrod is supported by NIH grant CA113004.

References

- 1.Cairns J. Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature. 1975;255:197–200. doi: 10.1038/255197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves M. Darwinian medicine: a case for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nrc2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merlo LM. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:924–935. doi: 10.1038/nrc2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axelrod R. Evolution of cooperation among tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13474–13479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greaves M. Cancer causation: the darwinian downside of past success? Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:244–251. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00716-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elser JJ. Biological stoichiometry in human cancer. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagy JD. The ecology and evolutionary biology of cancer: a review of mathematical models of necrosis and tumor cell diversity. Math Biosci Eng. 2005;2:381–418. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2005.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vineis P. Cancer as an evolutionary process at the cell level: an epidemiological perspective. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson AR. Integrative mathematical oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:227–234. doi: 10.1038/nrc2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munsury Y. Modeling tumors as complex biosystems: an agent-based approach. In: Deisboeck TS, editor. Complex Systems Science in Biomedicine. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. pp. 573–602. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwab ED. Cancer as a complex adaptive system. Med Hypotheses. 1996;47:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis A. The ecosystem: an evolving concept viewed historically. Funct Ecol. 1997;11:268–271. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odum EP. Fundamentals of Ecology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Axelrod R. The evolution of cooperation. Science. 1981;211:1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.7466396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begon M. Ecology: Individuals, Populations, and Communities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall CAS. Ecosystem Modeling in Theory and Practice: An Introduction with Case Histories. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitching R. Systems Ecology: An Introduction to Ecological Modeling. St. Lucia, Queensland: University Queensland Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricklefs R. Ecology. New York, NY: WH Freeman; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhowmick NA. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowther M. Microenvironmental influence on macrophage regulation of angiogenesis in wounds and malignant tumors. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:478–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones JL. Primary breast myoepithelial cells exert an invasion-suppressor effect on breast cancer cells via paracrine down-regulation of MMP expression in fibroblasts and tumour cells. J Pathol. 2003;201:562–572. doi: 10.1002/path.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly PM. Macrophages in human breast disease: a quantitative immunohistochemical study. Br J Cancer. 1988;57:174–177. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olumi AF. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephens TC. Repopulation of gamma-irradiated Lewis lung carcinoma by malignant cells and host macrophage progenitors. Br J Cancer. 1978;38:573–582. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1978.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sternlicht MD. The human myoepithelial cell is a natural tumor suppressor. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1949–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson AR. Tumor morphology and phenotypic evolution driven by selective pressure from the microenvironment. Cell. 2006;127:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhowmick NA. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elenbaas B. Heterotypic signaling between epithelial tumor cells and fibroblasts in carcinoma formation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:169–184. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu M. Microenvironmental regulation of cancer development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orimo A. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tlsty TD. Stromal cells can contribute oncogenic signals. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11:97–104. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinberg R. Eighteenth Annual Pezcoller Symposium: tumor microenvironment and heterotypic interactions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11550–11553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatenby RA. A microenvironmental model of carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nrc2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aranda-Anzaldo A. Cancer development and progression: a non-adaptive process driven by genetic drift. Acta Biotheor. 2001;49:89–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1010215424196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cahill DP. Genetic instability and darwinian selection in tumours. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:M57–M60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crespi BJ. Positive selection in the evolution of cancer. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2006;81:407–424. doi: 10.1017/S1464793106007056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawsawi NM. Breast carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and their counterparts display neoplastic-specific changes. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2717–2725. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuller E. The Dodo: Extinction in Paradise. Piermont, NH: Bunker Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allgayer H. An introduction to molecular targeted therapy of cancer. Adv Med Sci. 2008;53 doi: 10.2478/v10039-008-0025-9. doi:10.2478/v10039-008-0025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones SE. Metastatic breast cancer: the treatment challenge. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:224–233. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasui H. Novel molecular-targeted therapeutics for the treatment of cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:470–480. doi: 10.2174/187152008784533099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coffey DS. Hyperthermic biology and cancer therapies: a hypothesis for the “LanceArmstrong effect”. JAMA. 2006;296:445–448. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dewhirst MW. Re-setting the biologic rationale for thermal therapy. Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:779–790. doi: 10.1080/02656730500271668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahn GM. Thermochemotherapy: synergism between hyperthermia (42–43 degrees) and adriamycin (of bleomycin) in mammalian cell inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:937–940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brizel DM. Radiation therapy and hyperthermia improve the oxygenation of human soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5347–5350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roti Roti JL. Nuclear matrix as a target for hyperthermic killing of cancer cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:245–255. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0245:nmaatf>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westermann AM, et al. First results of triple-modality treatment combining radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hyperthermia for the treatment of patients with stage IIB, III, and IVA cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:763–770. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pienta KJ. The “emigration, migration, and immigration” of prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2005;4:24–30. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2005.n.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shiozawa Y. The bone marrow niche: habitat to hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells, and unwitting host to molecular parasites. Leukemia. 2008;22:941–950. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clines GA. Molecular mechanisms and treatment of bone metastasis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e7. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guise TA. The vicious cycle of bone metastases. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2002;2:570–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loberg RD. Pathogenesis and treatment of prostate cancer bone metastases: targeting the lethal phenotype. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8232–8241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:584–593. doi: 10.1038/nrc867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ryan CJ. Angiogenesis inhibition plus chemotherapy for metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer: history and rationale. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:250–253. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baka S. A review of the latest clinical compounds to inhibit VEGF in pathological angiogenesis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10:867–876. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flaherty KT. Sorafenib: delivering a targeted drug to the right targets. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:617–626. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tucker GC. Integrins: molecular targets in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006;8:96–103. doi: 10.1007/s11912-006-0043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bagnato A. The endothelin axis in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1443–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lalich M. Endothelin receptor antagonists in cancer therapy. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:785–794. doi: 10.1080/07357900701522588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adachi Y. The blockade of IL-6 signaling in rational drug design. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1217–1224. doi: 10.2174/138161208784246072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallner L. Inhibition of interleukin-6 with CNTO328, an anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, inhibits conversion of androgendependent prostate cancer to an androgen-independent phenotype in orchiectomized mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3087–3095. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gallagher JC. Advances in bone biology and new treatments for bone loss. Maturitas. 2008;60:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fuller K. Cathepsin K inhibitors prevent matrix-derived growth factor degradation by human osteoclasts. Bone. 2008;42:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lipton A. Treatment of bone metastases and bone pain with bisphosphonates. Support Cancer Ther. 2007;4:92–100. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2007.n.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luo FR, et al. Identification and validation of phospho-SRC, a novel and potential pharmacodynamic biomarker for dasatinib (SPRYCELTM), a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:1065–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith MR. Osteoclast targeted therapy for prostate cancer: bisphosphonates and beyond. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bierie B. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Biswas S. Inhibition of TGF-beta with neutralizing antibodies prevents radiation-induced acceleration of metastatic cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1305–1313. doi: 10.1172/JCI30740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pardali K. Actions of TGF-beta as tumor suppressor and pro-metastatic factor in human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:21–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stover DG. A delicate balance: TGF-beta and the tumor microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:851–861. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Helder MN. Stem cells from adipose tissue allow challenging new concepts for regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1799–1808. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knippenberg M. Prostaglandins differentially affect osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2495–2503. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Post S. Demonstration of the presence of independent pre-osteoblastic and pre-adipocytic cell populations in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone. 2008;43:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang DC. cAMP/PKA regulates osteogenesis, adipogenesis and ratio of RANKL/OPG mRNA expression in mesenchymal stem cells by suppressing leptin. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shiozawa Y, et al. Annexin II/Annexin II receptor axis regulates adhesion, migration, homing, and growth of prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:370–380. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doupis J. DPP4 inhibitors: a new approach in diabetes treatment. Adv Ther. 2008;25:627–643. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Focosi D. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell engraftment by inhibition of CXCL12 proteolysis with sitagliptin, an oral dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitor: a report in a case of delayed graft failure. Leuk Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hassane DC. Discovery of agents that eradicate leukemia stem cells using an in silico screen of public gene expression data. Blood. 2008;111:5654–5662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hastie C. Interferon-gamma reduces cell surface expression of annexin 2 and suppresses the invasive capacity of prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12595–12603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800189200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pelus LM. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization: new regimens, new cells, where do we stand. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:285–292. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328302f43a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanabar V. Heparin and structurally related polymers attenuate eotaxin-1 (CCL11) release from human airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:833–842. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oliveira MS. Suppressive effects of nitric oxide-releasing prednisolone NCX-1015 on the allergic pleural eosinophil recruitment in rats. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coelho FM, et al. The chemokine receptors CXCR1/CXCR2 modulate antigen-induced arthritis by regulating adhesion of neutrophils to the synovial microvasculature. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2329–2337. doi: 10.1002/art.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang AL. CTLA4 expression is an indicator and regulator of steady-state CD4+ FoxP3+ T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:1806–1813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lens M. Anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody ipilimumab in the treatment of metastatic melanoma: recent findings. Recent Patents Anticancer Drug Discov. 2008;3:105–113. doi: 10.2174/157489208784638767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guruvayoorappan C. Tumor versus tumor-associated macrophages: how hot is the link? Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7:90–95. doi: 10.1177/1534735408319060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sica A. Cancer related inflammation: the macrophage connection. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yuan A. Pathophysiology of tumor-associated macrophages. Adv Clin Chem. 2008;45:199–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bierie B. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates mammary carcinoma cell survival and interaction with the adjacent microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1809–1819. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.DeNardo DG. Immune cells as mediators of solid tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Johansson M. Polarized immune responses differentially regulate cancer development. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loberg RD. Targeting CCL2 with systemic delivery of neutralizing antibodies induces prostate cancer tumor regression in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9417–9424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lu Y. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 mediates prostate cancer-induced bone resorption. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3646–3653. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Kuijk AW. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study to identify biomarkers associated with active treatment in psoriatic arthritis: effects of adalimumab treatment on synovial tissue. Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]