Abstract

Loss of redox homeostasis and formation of excessive free radicals play an important role in the pathogenesis of kidney disease and hypertension. Free radicals such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) are necessary in physiologic processes. However, loss of redox homeostasis contributes to proinflammatory and profibrotic pathways in the kidney, which in turn lead to reduced vascular compliance and proteinuria. The kidney is susceptible to the influence of various extracellular and intracellular cues, including the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), hyperglycemia, lipid peroxidation, inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors. Redox control of kidney function is a dynamic process with reversible pro– and anti-free radical processes. The imbalance of redox homeostasis within the kidney is integral in hypertension and the progression of kidney disease. An emerging paradigm exists for renal redox contribution to hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2047–2089.

-

Redox Control of Cellular Function: How Is It Achieved?

-

Pathologic Role of ROS in Hypertension

-

NAD(P)H Oxidase Inhibition for the Treatment of Hypertension: Promises and Limitations

I. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have evolved to play an important role in routine physiologic and cellular processes. ROS and free radical formation influence pathways involved in innate immunity, cell and tissue growth, angiogenesis, cell signaling, salt and fluid homeostasis, biochemical reactions, apoptosis, etc. Free radicals such as superoxide anion (O2·−), hydroxyl moiety (·OH), hypochlorite (ClO−), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), and protein and lipid species are short lived, and after their role in the routine cellular maintenance is over, they are scavenged by a series of antioxidant enzymes (Table 1 and Fig. 1). However, after repeated exposure to external stimuli, an imbalance of reduction/oxidation (redox) control contributes to an excess of ROS and other free radicals. This is especially relevant in the pathogenesis of chronic disease states, including kidney disease and hypertension (172).

Table 1.

Examples of ROS and RNS and Oxidized Lipid, Protein, and DNA Moieties

| ROS | RNS | Lipid, protein, DNA moieties |

|---|---|---|

| O2•− | NO | oxLDL |

| 1O2 | ONOO− | •LOO |

| 3O2 | NO+ | •LO |

| H2O2 | NO− | LOONO |

| •OH | LONO | |

| ClO− | ||

| HOCl− |

O2•−, superoxide anion; 1O2, singlet oxygen; 3O2, ozone; •OH, hydroxyl anion; ClO−, chlorite ion; HOCl−, hypochlorite anion; ONOO−, peroxynitrite; NO+, nitrosonium ion; NO−, nitroxyl anion; oxLDL, oxidized LDL; •LOO, lipid peroxyl; •LO, lipid alkoxyl.

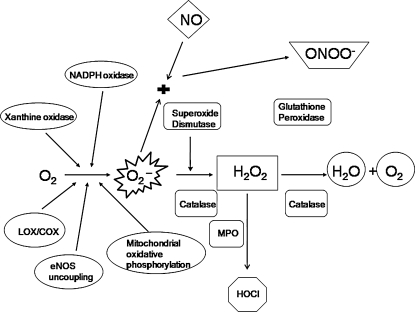

FIG. 1.

Pro- and antioxidants in cells. Superoxide anion (O2·−) is generated from oxygen (O2) by various oxidases including NAD(P)H oxidase. O2·− generated from enzymatic processes is dismutated to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase (SOD). Antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase and catalase break down H2O2 into H2O and O2, effectively terminating the cycle. Cells expressing myeloperoxidase (MPO) can convert H2O2 to hypochlorite (HOCl). O2·− can react with nitric oxide (NO) to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−), another potent oxidant.

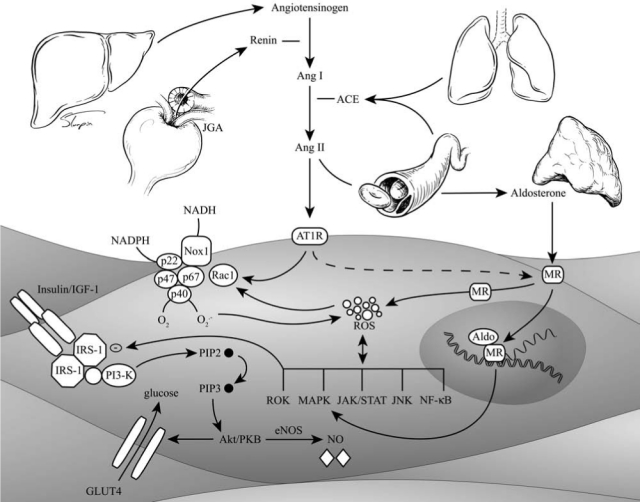

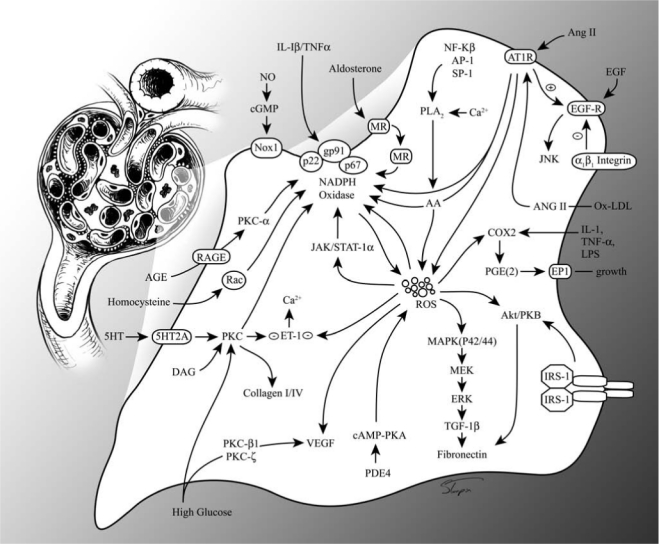

Increases in the chronic disease burden have led to identification of several important modifiers of the cellular redox mechanisms. Important among the modifiers are Ang II, aldosterone, hyperglycemia/hyperinsulinemia, modified lipids, high salt, and the peripheral nervous systems, including sympathetic and dopaminergic systems (Fig. 2). Modification of cellular redox mechanisms results in the abnormal production of O2·− and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which are mediators of many downstream signaling pathways, such as transcription factors, tyrosine kinases/phosphatases, ion channels, mitogenic factors, and cytokines. Through these signaling pathways, ROS have distinct functional effects in the kidney and various renal cellular mechanisms, including tubular sodium transport, tubuloglomerular feedback, medullary blood flow, cell migration and growth, hypertrophy, expression of inflammatory and extracellular matrix genes, and apoptosis. The effects of ROS generated within various components of the kidney ultimately depend on the locally generated concentrations and the balance of pro- and antioxidant pathways.

FIG. 2.

Classic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway and angiotensin II (Ang II)/insulin signaling in the vascular smooth muscle cell. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; Aldo, aldosterone; IGF-1, insulin growth factor1; IRS-1, insulin-receptor substrate; PKB, protein kinase B; PIP, phosphatidyl inositol phosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B.

The purpose of this review is to describe the important mechanisms that contribute to generation of oxidative stress and hypertension in the kidney and the extrarenal vascular contribution to hypertension. Further, we review pathways with antioxidant properties that support a link with hypertension. Last, we discuss ways to reduce oxidative stress–mediated renal injury.

II. Redox Control of Cellular Function: How Is It Achieved?

A. Free radical contribution to redox control of hypertension

Free radicals can broadly be subdivided into ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Table 1). These are generated for specific cellular processes: second messengers in cell-cycle progression, smooth muscle relaxation and inhibition of platelet adhesion, cell growth and differentiation, phagocytosis, production of cytokines [e.g., interleukin-2 (IL-2)], stimulation of hemoxygenase-1 (HO-1), activation of transcription factors [e.g., nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)], insulin signaling, and others. In the kidney, ROS are involved in erythropoiesis, sodium handling, and fluid homeostasis, as discussed in greater detail in later sections.

The predominant form of ROS is the O2·− (Fig. 1 and Table 1). In the mitochondria, most of the O2·− is generated by leakage from the electron-transport chain (nonenzymatically produced by semiubiquinone) and the Krebs cycle (278). This constitutes 2% of all electron-transport chain by-products; the remaining 98% goes toward producing O2 and H2O. In overall quantitative terms, mitochondrial electron-transport chain–generated O2·− may be the most important source (278). O2·− also is produced by metabolic oxidases, including nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate [NAD(P)H] oxidase, xanthine oxidase (XO), P-450 monooxygenase, lipooxygenase (LOX), and cyclooxygenase (COX) (278). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) converts O2·− into H2O2, which is detoxified into H2O by either glutathione peroxidase (GPx) or catalase. H2O2 can oxidize chloride to form the reactive HOCl− in cells that express myeloperoxidase (MPO). HOCl− can react with O2·− to form OH. HOCl− can further react with H2O2 to produce singlet oxygen (1O2). Excess O2·− also reduces transition metal ions such as Fe3+ and Cu2+, the reduced forms of which, in turn, can react with H2O2 to produce ·OH (Fenton and Haber–Weiss reactions, respectively). ·OH is the strongest of the oxidant species and reacts indiscriminately with nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins. No detoxification system is known for OH; therefore, scavenging OH is a critical antioxidant process.

The NO radical (NO·) is produced by oxidation of one of the terminal nitrogen atoms of l-arginine; this reaction is catalyzed by nitric oxide synthase (NOS). NO is consumed by ROS in a series of reactions that leads to diminished levels of this important vasodilator. NO can be converted to other RNS, such as nitrosonium cation (NO+), nitroxyl anion (NO−), or peroxynitrite (ONOO−). O2·− rapidly reacts with NO to yield ONOO−, which may later dissociate into NO and ·OH. ONOO−, oxidizes the zinc-thiolate center of NO synthase, which results in decreased production of NO. H2O2 reacts with heme center of MPO to produce FeIV, which in turn oxidizes NO to NO2−. Another important interaction between ROS and NO is the oxidation of NO cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). In the absence of BH4, NOS forms O2·− instead of NO, a process called NO uncoupling, leading to increased oxidative stress. ROS also induce lipid and protein peroxidation, generating various reactive compounds such as lipid peroxyl (·LOO) and lipid alkoxyl radicals (·LO).

B. Clinical contribution to redox control of hypertension

Environmental and cellular cues that increase production of ROS include activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system with elevated levels of angiotensin II (Ang II) and aldosterone, lipids, insulin resistance with subsequent hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia with formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), as well as mechanical shear forces (Figs. 2 and 3). These ROS-generating cues are present at increased levels in certain populations genetically predisposed to hypertension and renal disease (64). Classically this has been observed in individuals that display obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and other components that compose the cardiometabolic syndrome [e.g., any pathophysiologic state characterized by elevated plasma lipids, of the modified (ox-LDL) or unmodified type, are associated with generation of ROS, redox imbalance, and oxidative stress and are known to contribute to hypertension (Fig. 4)]. The cholesterol lowering achieved after short-term use of an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor (statin) therapy is associated with a decrease in ONOO−-mediated oxidative stress and an improvement in large-artery distensibility. Indeed, the use of statins alone or in combination with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) improved antiatherosclerotic endothelial expression of quotient Q, which includes the NAD(P)H oxidase subunit gp91phox (Nox2) expression.

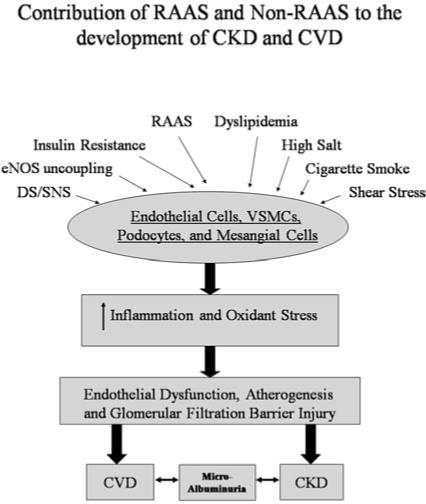

FIG. 3.

RAAS- and non-RAAS-mediated mechanisms in control of cardiovascular disease, albuminuria, and chronic kidney disease. Extra- and intracellular cues, including RAAS, high glucose, eNOS uncoupling-generated ROS, cigarette smoke, DS/SNS, oxidized lipids, shear stress, and high salt, modulate the function of endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, podocytes, and mesangial cells through oxidative stress and inflammation. This results in endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and glomerular filtration barrier injury. The hallmark of this triad is proteinuria, which is a marker for both cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

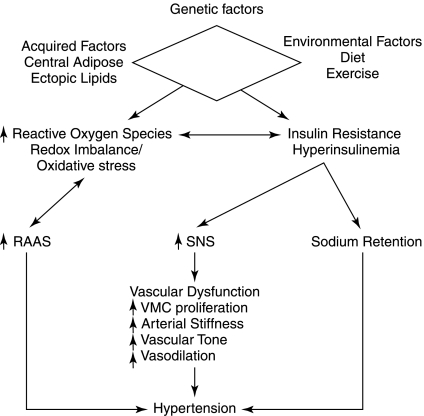

FIG. 4.

The relation between genetic, environmental, and acquired factors contributing to the redox contribution to insulin resistance and hypertension. These interactions result in activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity, and sodium retention, leading to vascular dysfunction and subsequent hypertension and increased cardiovascular risk. VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

In addition to ox-LDL, hyperglycemia by itself can lead to oxidative stress and hypertension in normal subjects and in people with diabetes (26). In healthy human subjects, administration of methacholine in euglycemia resulted in decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilation after the cohort was subjected to 6 h of acute hyperglycemia (10). Concurrent administration of the antioxidant vitamin C abrogated hyperglycemia-induced changes. The authors postulated that hyperglycemia inhibits endothelium-dependent vasodilation through preferential production of O2·− over NO, and vitamin C scavenges the extracellular oxygen-derived free radicals. Furthermore, the work of other investigators on hyperglycemia has led to the hypothesis that oxidative stress in this condition is a result of imbalances between oxidant-sensitive mechanisms and NO availability (39). Oxidative stress is attenuated by free radical scavengers that indirectly increase NO bioavailability (10, 323). Other pathways through which hyperglycemia may promote O2·− production are glucose autooxidation, advanced glycation end products (AGE) signaling, abnormal arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism and its coupling to cyclooxygenase catalysis, protein kinase C activation, depletion of BH4, and wall shear stress (10, 26, 242, 301, 323). As mentioned, hyperglycemia contributes to the formation of AGEs, examples of which include pentosidine, carboxymethyllysine, carboxyethyllysine, and argpyrimidine. These have been shown to have direct effects on oxidative stress via binding to the receptor for AGE (RAGE) (229, 290). Furthermore, blockade of RAGE resulted in abrogation of oxidative stress. This evidence is derived largely from small animal investigations and clinical trials using aminoguanidine (a.k.a., pimagedine) in Aminoguanidine Clinical Trial in Overt Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy (ACTION-II) and Alt-711 (a.k.a., alagebrium) in phase 2b Systolic Pressure Efficacy and Safety Trial of Alagebrium (SPECTRA) (7, 69). In the insulin-resistant state, hyperglycemia has been shown to have deleterious effects on vascular fluid dynamics, thereby contributing to hypertension.

C. Prooxidant enzymes and pathways

1. NAD(P)H oxidase

The enzyme complex better known as NAD(P)H oxidase is now well recognized as a major source of ROS production in vascular and renal cells (91, 248). More important, it is the enzyme complex responsible for generating Ang II-mediated O2·− in the vast majority of cardiovascular diseases including hypertension (278). The structure and function of this enzyme complex have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (6). In brief, the phagocyte enzyme complex is made up of both membrane and cytosolic components. The membrane complex consists of two subunits, gp91phox (phox stands for phagocyte oxidase), a 91-kDa protein, and p22phox, a 22-kDa protein, which together form a heterodimer, flavocytochrome b558 (154). The membrane complex is inactive under normal cell-resting conditions (an exception may be Nox4, a 66-kDa gp91phox homologue expressed in nonphagocytic cells and other Noxes expressed in nonphagocytic cells). Cytosolic components include p47phox, or its homologue NoxO1 (expressed in nonphagocytic cells), which is considered an organizer subunit, as it is strategically phosphorylated when activated. Under unstimulated conditions, the bis-SH3 domain (contains tandem repeats of SH3) is not available for binding to the proline-rich region (PRR) of p22phox because of being buried in an autoinhibitory region (AIR). On stimulation, serine phosphorylation of the AIR occurs, uncovering the bis-SH3 domain for interaction with the membrane complex cyt b558 (specifically PRR of p22phox). An additional PX domain facilitates binding to the membrane phosphatidylinositol groups. p67phox (67-kDa protein) and p40phox (40-kDa protein) are the other cytosolic components with PRR binding and activation domains (ADs). The AD in p67phox facilitates transfer of hydride ion from NAD(P)H to FAD on interaction with small G-protein Rac through the tetratricopeptide domain (TPR) of p67phox. The Rac proteins themselves exist in an inactive state when bound to GDP; however, phosphorylation leads to activated Rac-GTP and translocation to the NAD(P)H membrane complex. p40phox binds to p67phox through its counterpart phox/Bem1 (PB1) and facilitates the assembly of p47 phox−p67phox at the membrane through an additional lipid PX binding to the membrane. The final transfer of an electron to form O2·−is facilitated by two heme groups present within the NAD(P)H multisubunit complex.

Several mutations have been identified in the phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase subunits, leading to a condition known as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). This disease condition is characterized by the inability of the organism to kill engulfed bacteria by production of O2·− and other free radicals. Whereas mutations in gp91phox are inherited as an X-linked trait, mutations in other subunits are inherited as autosomal recessive conditions. So far, no mutation has been identified in the human p40phox gene, contributing to chronic granulomatous disease (CGD); however, p40phox knockout mice exhibit CGD defects similar to those of other subunit knockouts (60). Importantly, characterization of a mutation in the phox homology domain of the NAD(P)H oxidase component p40phox identified a mechanism for negative regulation of O2·− production (30).

The nonphagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase differs substantially from its phagocytic counterpart (Table 2). It is constitutively active under resting conditions, which means all subunits must be in their active conformation and together in the cell. Li et al. (182) showed that the nonphagocytic enzyme complex resides mostly in a perinuclear pattern in endothelial cells. Whereas the phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase can generate millimolar quantities of O2·− under stimulation, the nonphagocytic counterpart produces only micromolar quantities. It is now believed that the constitutively active NAD(P)H oxidase present in nonphagocytic cells is the original NAD(P)H oxidase, and the highly regulated, damaging version active only in respiratory bursts is the mutated and evolved enzyme (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences between Phagocytic and Renal NAD(P)H Oxidase Enzyme (Li and Shah)

| NAD(P)H oxidase subunit and enzyme function | Phagocytic | Renal |

|---|---|---|

| gp91phox (NOX2) | Only isoform | Several isoforms including gp91phox or Nox2, Nox1, and Nox4 |

| p22phox | Forms heterodimer with gp91phox and resides in the plasma membrane | Also forms heterodimer but may reside intracellularly associated with cytoskeleton, as in endothelial cells |

| p47phox | Activator subunit that helps translocation of cytosolic complex to the membrane | May have similar role to phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase for Nox2. However, may not be needed or may be replaced with NoxO1 for Nox1 |

| p67phox | Organizer subunit that helps keep cytosolic proteins in their inactive state | May have similar role to phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase for Nox2. However, may not be needed or may be replaced with NoxA1 for Nox1 |

| p40phox | Adaptor subunit | Very little is known about function |

| FAD and heme groups | 1 FAD and 2 heme groups complete the cytochrome | Heme groups are missing |

| Activity | Has to be activated; superoxide levels are very high in the “phagosomes” | Constitutively active at low levels; even under stimulus, the levels of superoxide generated are lower than phagocytes |

| Substrate | NADPH | May use NADH, especially Nox4 |

| Assembly | Components in inactive state, separated between cytosol and plasma membranes | Components are preassembled intracellularly |

| Superoxide production | Extracellular in “phagosomal” compartment | Intracellular |

NAD(P)H oxidase is regulated by agonist-induced activation and antagonist-induced suppression. Agonist-induced mechanisms include upregulation of the p47phox subunit by Ang II, tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), and pure pressure with helium gas, among other stimuli (141, 180, 378). This was corroborated in p47phox knockout mice, which demonstrate complete loss of agonist stimulation. Antagonists including NO are capable of suppressing NAD(P)H oxidase activity, illustrated best in mesangial cells by the downregulation of Nox1 (255).

Importantly, feedback mechanisms may be involved in the maintenance of low, constitutively active NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated ROS during physiologic processes. An example of such a regulation is the increased turnover of ubiquinated Rac1 in the presence of excess H2O2 and decreased turnover of Rac1 in the presence of NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitors like diphenyliodonium (DPI) (169). Conversely, exogenous exposure of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) or fibroblasts to H2O2 activates NAD(P)H oxidase to generate more superoxide anion, displaying a feed-forward process (185). The feed-forward mechanism may play a role in NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent oxidative stress in a variety of disease processes, including insulin resistance, hypertension, and kidney disease.

The roles of NAD(P)H oxidase in mediation of redox homeostasis and hypertension are reviewed in later sections.

2. Xanthine oxidase (XO)

XO was first proposed to play an important role in generating vascular oxidative stress in the hearts of chronically ethanol-treated rats (239). Since then, several groups have focused on the role of this enzyme in generating oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Data from double transgenic rats (dTRs) harboring both human renin and angiotensinogen genes suggests endothelial function of renal arterial rings was impaired (213). Moreover, relaxation was improved with superoxide scavenger SOD and oxopurinol, an XO inhibitor. Blockade of the angiotensin-receptor type 1 (AT1R) normalized blood pressure, oxidative stress measures, endothelial dysfunction, and the contractile responses. This supports another mechanism by which the RAAS and elevated Ang II contribute to endothelial dysfunction, redox and oxidative stress in the vasculature. However, conflicting reports exist on the function of XO in redox control of the kidney.

As discussed earlier, hypercholesterolemia is an important risk factor for the progression of kidney disease and contributes to redox imbalance and oxidative stress, potentially causing endothelial dysfunction via XO. To elucidate a contribution of XO activity and redox control of kidney function, investigators incorporated a pig model of hypercholesterolemia to evaluate renal hemodynamics (45). While infusing oxypurinol into the kidneys, they measured renal hemodynamics before and after endothelium-dependent (acetylcholine, ACh) and -independent (sodium nitroprusside) challenge. Hypercholesterolemic pigs demonstrated elevated oxidative stress, higher plasma uric acid, lower urinary xanthine, and greater renal XO expression compared with controls. Inhibition of XO with oxypurinol significantly improved the blunted responses to ACh of cortical perfusion, renal blood flow, and glomerular filtration rate, restored medullary perfusion, and, in addition, improved the blunted cortical perfusion response to sodium nitroprusside, further supporting a role for XO in redox control of the kidney. Alternatively, XO levels have been shown to be down-regulated in the 5/6 nephrectomized rats, as well as a rat model of mesangioproliferative anti-Thy 1.1 GN (glomerulonephritis) (76). NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent increases in ROS production were observed, but XO levels were not changed in these animal models. Furthermore, another study in Dahl salt-sensitive (DSS) rats showed an increase in NAD(P)H and mitochondrial sources of ROS and no change in XO levels (320).

The contribution of XO to renal redox control of hypertension may be more apparent as it relates to uric acid. Uric acid, an end product of the xanthine oxidase pathway, has been proposed both to have antioxidant and oxidant properties (145, 311). The antioxidant property of uric acid may relate to its ability to scavenge free radicals, including O2·−, ·OH, and singlet oxygen, and to increase the levels of extracellular SOD (ecSOD), thereby preventing endothelial NOS (eNOS) uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction (121, 145). Although elevated levels of uric acid may confer protective antioxidant effects on the vasculature and the kidneys, the correlation with cardiovascular disease risk is not readily apparent (145). Interestingly, elevated serum uric acid levels have been proposed as a marker for cardiovascular dysfunction and renal disease (145, 149, 152, 311). Administration of uricase inhibitor, oxonic acid (OA), has been used extensively to study the detrimental effects of increased uric acid levels. Experimentally increased uric acid levels result in accelerated renal-disease progression by variably increasing systolic BP, afferent glomerular arteriolopathy, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in different rat models, and administration of allopurinol reversed these deleterious effects (149, 158). In addition, reduction of BP with enalapril and potentiation of NO with NOS substrate L-arginine also variably improved renal function (209, 283). However, the role of uric acid as a risk factor for kidney disease is largely unknown (145). Whereas it appears that reducing uric acid levels in early kidney disease may be useful, established kidney disease is less responsive to treatment with uric acid–reducing agents, as other factors including salt sensitivity of kidneys may predominate. Moreover, clinical trials, including the Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study, have failed to show association of uric acid levels with kidney-disease progression. Interestingly, the GREek Atorvastatin and Coronary heart disease (CHD) Evaluation (GREACE) and LIFE studies reopened a fierce debate on the benefits of uric acid–level monitoring in a subset of patients with more-severe CVD risk (311).

3. Lipooxygenases (LOX) and cyclooxygenases (COX)

LOX and COX produce oxidative stress through NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent and –independent pathways (29, 195). Ang II treatment of rat aortic smooth muscle cells induced 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX), resulting in an increased production of leukotriene B(4) [LTB(4)]. LTB(4) stimulated NAD(P)H oxidase and downstream IL-6 transcripts through generation of ROS. Reversal of oxidative stress through inhibition of LOX and COX via AT1R blockade as well as NSAIDS/aspirin has been shown to modulate kidney function (83, 339). Further, COX-2 expression was increased in N(omega)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)–treated Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats, along with blood pressures and urinary isoprostanes (325). Indeed, NS-398, a COX-2–specific inhibitor, reversed L-NAME-mediated hypertension and proteinuria through reductions in COX-2 and oxidative stress, implicating COX-2 as an important mediator of oxidative stress and hypertension. COX-2 inhibition has been further shown to alter renal hemodynamics, suggesting a role for this enzyme in redox control of the kidney (33, 119, 162, 170, 263).

Prostaglandins (PGs), products of COX, have important physiologic roles in maintaining vascular tone, salt and fluid homeostasis, and renin release. In the kidneys, salt deprivation activates Ang II, which in turn inhibits renin production once homeostasis is achieved. One pathway that has been proposed to participate in this feedback loop is COX-2–mediated suppression of renin in the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA) (382). This is a long-term effect. However, before homeostasis is achieved, salt deprivation due to insufficient salt intake or diuretic adminstration contributes to increases in COX-2 expression in the cortical part of the thick ascending loop of Henle (cTALH) and JGA, leading to increase in renin release and subsequent activation of the RAAS. Thus, PGs contribute to the tubuloglomerular-feedback (TGF) response to low-salt delivery to macula densa by increasing Ang II levels and by preventing Ang II from decreasing the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). In animal models, blockade of the AT1R and ACE inhibition increase the expression of COX-2 in the macula densa. Furthermore, AT1A inhibition potentiated Ang II actions via AT2 receptors, resulting in further increases in COX-2 expression.

Interestingly, some investigators propose that COX-2 expression may be regulated in response to local chloride concentrations and not sodium concentrations (109), whereas others propose that it is the sodium load regulating COX-2 expression (170). In the renal medulla, COX-2 is regulated in a manner opposite that of the cortex. COX-2 expression decreases with salt deprivation and increases with high-salt diets to promote adaptation of medullary interstitial cells to hypertonic stress (34). Use of an NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) in primary cultures of rabbit cTALH leads to increased expression of COX-2 in the cTALH (35) through NF-κB and p38MAPK pathways. COX-2 is expressed in the macula densa, cTALH, medullary interstitial cells, and podocytes.

In addition to the normal physiologic role of COX-2, its role in increasing oxidative stress, inflammation, hypertension, and proteinuria has generated considerable interest. Several animal models that demonstrate hyperfiltration also demonstrate increased COX-2 expression; including the subtotal renal-ablation model, the streptozotocin-induced diabetes model, and the diabetes plus deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) salt-hypertension model (34). Long-term treatment with COX-2 inhibitors in these models significantly decreased proteinuria and reduced extracellular matrix deposition, as indicated by decreases in immunoreactive fibronectin expression and mesangial matrix expansion. These studies exemplify the complex role of COX-2.

4. P450 monooxygenase and mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes (I-IV)

Although P450 monooxygenase has been proposed to play a role in the redox control of kidney function, little evidence exists of this enzyme in this role (1, 262). Importantly, the P4502E1 isoform has been proposed to be activated by ·OH and, by positive feedback, acts as an iron donator and for further production of ·OH through the Fenton reaction. In addition, this isoform was found at five-to eightfold higher levels in kidneys of streptozotocin-treated rats. Importantly, the mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes (I-IV) have been proposed to play important physiologic and pathologic roles in the vasculature and the kidney. Complex I and III are the major sites of superoxide production, which is an unavoidable byproduct of ATP generation in the mitochondria. Mitochondrial ROS have also been proposed to play important roles in cellular signaling processes. Autosomal recessive mutations in the coenzyme Q(10) protein leads to glomerular damage via decreased activity of complex II + III in abnormal mitochondrions in podocytes (54). Blockade of mitochondrial complex I leads to lack of ureteric bud-branching morphogenesis in response to high glucose (383). Hyperglycemia induces mitochondrial electron-transport chain enzymes in cultured human mesangial cells to increase ROS production, leading to NF-κB activation and COX-2 protein expression (162). The renal outer medulla is considered to be the major site for mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme–mediated ROS production and, together with nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NADH) oxidase (not NADPH oxidase), has been implicated in regulation of medullary blood flow (MBF) and sodium excretion (387). DETC (a SOD inhibitor) decreased MBF and increased sodium retention and hypertension, whereas the SOD mimetic, tempol, had the opposite effects, demonstrating that O2·− is vasconstrictive and antinatriuretic. In addition to unmasking NO-induced vasodilation, tempol has other effects on O2·−. Among the proposed mechanisms are reduction in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, thereby keeping the vascular smooth muscle cells relaxed and preventing inhibition of prostacycline (PGI2).

Importantly, several lines of evidence indicate that hypertension may be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction through mechanisms involving increased ROS production and RAAS activation (253, 326). Losartan attenuates renal mitochondrial dysfunction in SHRs and decreases proteinuria (48). Pretreatment of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats with losartan was associated with lower mitochondrial H2O2 production, kidney structural damage, and proteinuria (47). The benefits of losartan were shown to be beyond its blood pressure–lowering effects, as treatment with amlodipine also lowered BP but did not have the improvement in mitochondrial dysfunction (47). Interestingly, Ang II has been shown to stimulate mitochondrial H2O2 production, leading to endothelial dysfunction via a PKC-dependent pathway; however, p22phox inhibition did abrogate mitochondrial H2O2 production, underscoring the role of NAD(P)H oxidase enzyme once again (56). Furthermore, a study by Kimura et al. (160) demonstrated that abrogation of mitochondrial ROS did not result in a decrease in the vasoconstriction induced by prolonged Ang II inhibition, although other benefits, including reduction in MAP kinase activity, were apparent. In spite of this conflicting report, the consensus points to an important role for mitochondria-generated ROS and hypertension via the mediation of RAAS and other cellular cues.

D. Antioxidant enzymes and pathways

O2·− free radicals are scavenged efficiently by cellular antioxidants when their normal functions (e.g., cellular signaling) are over (Fig. 1). Antioxidants, including SOD, convert O2·− to H2O2, which is then converted to O2 and H2O by catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). Under certain conditions of excess O2·− or depleted SOD and catalase enzymes, the thioredoxin (TRX)/glutaredoxin (GRX) system comes to the rescue of cells under attack from oxidants (15, 207, 302, 374). The TRX and GRX systems have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (15). In brief, the TRX system consists of cytosolic TRX1/TRXR1 and mitochondrial TRX2/TRXR2. Mammalian TRXs are homodimeric selenoenzymes containing an FAD and a penultimate COOH-terminal selenocysteine residue in their Gly-Cys-SeCys-Gly active site. Cytosolic TRX1 plays important roles as electron donors to enzymes forming disulfide bonds and exert redox control of transcription factors such as NF-κB. Mitochondrial TRX2 are essential for embryonic development and actively respiring cells. The GRX system consists of the glutathione redox couple (GSH/GSSG), glutathione reductase, and GRX. Humans have three types of GRXs; cytosolic GRX1 is an electron donor for enzymes forming disulfide bonds similar to cytosolic TRX1; mitochondrial GRX catalyzes the reversible glutathionylation of mitochondrial complex I. This modification of two critical thiol groups regulates the production of O2·− by the complex, and knockout of yeast mitochondrial GRX5 (yGRX5) led to constitutive oxidative damage (15, 276). The TRX/GRX enzyme systems are especially important in protecting against ischemia/reperfusion injury after myocardial infarction, atherosclerotic plaque rupture, left ventricular hypertrophy in congestive heart failure, and kidney oxidative stress. In SHRs and SHRSP rats, TRX levels were lower in kidneys by both immunohistochemistry/Western blots and real time PCR, when compared with those in normal WKY rats (319). Of note, whereas the roles of TRX/GRX systems are better understood in the cardiovascular disease, their role in the kidney is just emerging.

NO is another biomolecule with antioxidant functions, and decreased NO is associated with increased oxidative stress and hypertension (3, 23, 111, 118, 167). NO bioavailability has been shown to be decreased in advanced atherosclerotic lesions in humans attributed to lower expression of eNOS (361). A lack of substrate or cofactors for eNOS can lead to decreased bioavailability of NO (257). In addition, loss of endothelial pertussis toxin–sensitive G-protein function in atherosclerotic porcine coronary arteries showed that alterations of cellular signaling led to eNOS not being appropriately activated (300). Furthermore, accelerated NO degradation by ROS occurs because of kinetics favoring this reaction over scavenging of ROS by SOD (111). Overexpression of NO via delivery of neuronal NOS (nNOS) results in improvement in oxidative stress and hypertension through improved parasympathetic nerve transmission (116). However, NO is a complex molecule, and uncoupling of eNOS due to reduced levels of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) can lead to increased generation of O2·−; the interaction of NO and O2·− can lead to production of other oxidants including peroxynitrite (ONOO−). NO has important roles in the kidney, including regulation of medullary perfusion and pressure natriuresis, tubuloglomerular feedback, tubular sodium transport, and modulation of renal sympathetic nerves (224, 358). These roles of NO are discussed in further detail in section IVC.

E. Role of ROS in physiologic processes

Chronic inflammation and ROS have been implicated in the progression of insulin resistance, cardiovascular and kidney disease, and age-related diseases (Fig. 4). ROS serve a dual role not only in enabling immune cells to kill invading pathogens but also essential mediators of inflammatory signaling. This latter role is not limited to inflammation, but it is now known that these species serve as essential mediators of a wide array of signaling mechanisms, such as cell-cycle progression, growth, and proliferation, as well as insulin signaling and others. In addition to the contributions from metabolic oxidases such as NAD(P)H oxidase and xanthine oxidase, ROS are produced as by-products of mitochondrial aerobic metabolism, with ~2% of oxygen (O2) being converted to O2·− at any given time. Excess ROS, redox imbalance, and oxidative stress are thought to be the main cause underlying the aging processes and chronic diseases, as their electrophilic character allows them to oxidize cell constituents such as proteins, lipids, and DNA. The paradoxic nature of ROS can be resolved by understanding that only excessive production of these radicals results in damage, whereas their roles as mediators of cell signaling are temporally and spatially controlled. As an example, ROS are known to oxidize/reduce cysteine residues within proteins, a mechanism particularly active with MAPK, protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP), protein tyrosine kinase (PTK), transcription factors, and even other enzymes being redox regulated via their cysteine residues. This redox regulation allows the cell to activate/inhibit signaling proteins and hence dynamically to change gene expression according to external stimuli. NF-κB is a redox-regulated transcription factor involved in the activation of inflammatory signaling, and its constitutive activation may underlie its role as a long-term inflammatory mediator in the pathogenesis of age-related diseases.

ROS are involved in routine cell functions including (a) host defense, (b) cellular signaling, (c) gene expression, (d) cellular death and senescence, (e) regulation of cell growth, (f) oxygen sensing, (g) biosynthesis and protein crosslinking, (h) regulation of cellular redox potential, (i) reduction of metal ions, (j) regulation of matrix metalloproteinases, (k) angiogenesis, and (l) cross-talk with the nitric oxide system (11).

III. Pathologic Role of ROS in Hypertension

In general, increased production of ROS can lead to the development of insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart injury, congestive heart failure), acute and chronic kidney disease (precipitating factors for these include ischemic renal injury, hypertension, nephritis, obstructive nephropathy, glomerular damage, and rhabdomyolysis), obesity, cancers, and shock (sepsis, etc.) (Fig. 3). ROS can cause hypertension, as demonstrated by several lines of evidence (359). Rats administered lead in drinking water can generate O2·− and ·OH in blood vessels, which ultimately results in hypertension. Scavenging of ROS with vitamin E or ·OH scavenger dimethylthiourea prevented hypertension in these rats. It was further shown that development of oxidative stress can precede hypertension in the SHRs. Our laboratory also observed this phenomenon of oxidative stress preceding hypertension in Ren2 transgenic rats (unpublished observations). Interestingly, deletion of ecSOD results in oxidative stress and hypertension, whereas gene transfer to SHRs ameliorates hypertension. We and others also observed that tempol fails to “treat hypertension” (61, 358), although it has multiple beneficial effects, including reduction of oxidative stress, improvement in insulin sensitivity, reduction of myocardial remodeling, etc. This illustrates the complex relation between oxidative stress and hypertension and requires further clarification through studies. ROS can be generated by RAAS and non-RAAS–mediated mechanisms, and this section focuses on extrarenal ROS in the control of systemic and renal hypertension (Figs. 2, 3, and 5).

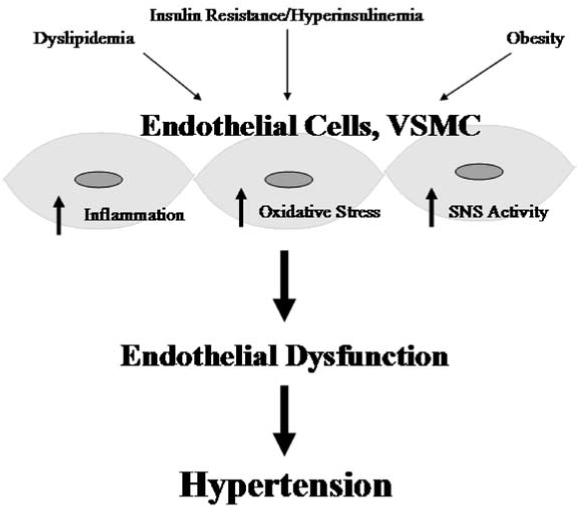

FIG. 5.

Schematic showing the link between cardiometabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, and obesity together lead to oxidative stress, inflammation, and increased sympathetic nervous system activity in the endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells of the vasculature. This creates redox imbalances and leads to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and an increased cardiovascular disease risk.

A. Non–RAAS-mediated oxidative stress in hypertension

1. High intravascular pressure

Elevated blood pressure, or hypertension, is characterized by increased hydrostatic pressure within the kidney arterial/arteriolar and intraglomerular systems. High pressure induces O2·− production in isolated arteries via protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase. In this experimental model system, reduction of high intraluminal pressure (Pi) with SOD, DPI, apocynin, and protein kinase C inhibitors (chelerythrine or staurosporin) or the removal of calcium during high-Pi treatment prevented the increases in O2·− production, whereas inhibition of the RAAS had no effect. The authors concluded that high Pi itself elicits arterial O2·− production, most likely by PKC-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase, thus providing a potential explanation for the presence of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in various forms of hypertension and the vasculo-protective effect of antihypertensive agents with different mechanisms of action (332). However, in subsequent in vivo studies, the same authors showed a partial effect of Ang II inhibitors and proposed that in vivo, a local RAAS-mediated control of redox homeostasis may exist. In a separate group of experiments in an aortic-coarctation animal model, hypertension per se was postulated to be enough to cause upregulation of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits above the coarctation (340).

2. Shear stress

As described in the previous sections, mechanical forces, comprising both unidirectional laminar and oscillatory shear, have been postulated to lead to alterations in the redox state in the kidney, resulting in differential expression of genes (247). Vascular studies suggest laminar shear stress to be beneficial to intimal health by upregulating eNOS and NO production, whereas oscillatory shear results in increased production of ROS via NAD(P)H oxidase and XO (49, 212). Increased ROS production then leads to a familiar cascade of events, leading to inflammation, growth, fibrosis, and scarring in the intimal portion of the vasculature, which ultimately contributes to kidney disease and hypertension.

Oscillatory shear stress, present at sites where atherosclerosis develops, appears to be a potent stimulus of O2·− production (110). Atherosclerotic lesions are found opposite vascular flow dividers at sites of low shear stress and oscillatory flow (49, 306). Continuous oscillatory shear stress leads to a sustained activation of prooxidant processes resulting in redox-sensitive gene expression in human endothelial cells. Steady laminar shear stress initially activates these processes but appears to induce compensatory antioxidant defenses. It is speculated that differences in the endothelial redox state, orchestrated by different regimens of shear stress, may contribute to the focal nature of atherosclerosis.

Although the majority of the evidence for oscillatory shear stress stems from the vascular investigations, limited evidence does exist in the kidneys (70). Podocytes have been shown to be sensitive to fluid shear forces in vitro, and mechanical stretch has been proposed as a mechanism that can lead to glomerulosclerosis. Specifically, in the presence of hypertension, NO may work in the kidney by inhibiting both mesangial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia (260). The efferent arteriole at the transition of the intraglomerular segment to the segment that passes through the extraglomerular mesangium has a conspicuously narrow portion with endothelial cells protruding into the vessel lumen. In addition, this segment is prominent for the expression of nNOS. Therefore, it has been proposed that this segment acts as a specific shear-stress receptor (58, 59, 123).

Collectively, these data suggest that elevated blood pressure and increased hydrostatic forces within the kidney contribute to excess ROS, redox imbalance, and oxidative stress mediated by several factors, including oscillatory shear and NO. Abrogation of high blood pressure is through a common Ca2+/PKC/p47phox-mediated pathway in the kidney.

3. Lipids

This class of molecules is important physiologically for nutrition, energy, membrane integrity, cellular signaling, binding, and transport of important minerals and vitamins. However, excessive amounts of lipids or modification of these lipids (i.e., dyslipidemia) directly contribute to altered redox homeostasis, oxidative stress, and hypertension (105, 241). Epidemiologic studies, such as the Helsinki Heart Study and Physician Health Study, demonstrate that higher levels of the LDL/HDL ratio (>4.4) and higher cholesterol levels are associated with rapidly deteriorating kidney function and hypertension, respectively (288). Further, high levels of cholesterol and LDL-C (e.g., ox-LDL) were predictors of risk for development of CKD in the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study (21).

Animal models for dyslipidemia-induced renal disease include genetic models (zucker obese and SHRs), diet-induced model (rat, guinea pig, and rabbit), and secondary hyperlipidemia model (DSS rat, mass-reduction kidney model). Rats fed a high-fat diet develop obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension via an increase in NAD(P)H oxidase activity in the kidney, as seen in other animal models (273), and this contributes to endothelial dysfunction via oxidant degradation of NO (112).

In addition, impaired redox homeostasis can result in the formation of ox-LDL, which further potentiates renal injury. A proatherosclerotic, vicious cycle of NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent ROS formation with an augmented generation and uptake of ox-LDL, which then causes further potentiation of oxidative stress by ox-LDL itself, has been proposed (277). ox-LDL promotes glomerulosclerosis, similar to the progression of atherosclerosis: both are characterized by the presence of LDL and ox-LDL; infiltration of monocytes/macrophages; and overexpression of adhesion molecules (e.g., monocyte chemotactic proteins, growth factors, and cytokines) within the lesions. Both LDL receptors, which bind native LDL, and scavenger receptors (SR-AI), receptors for ox-LDL and acetylated LDL, are expressed in glomerular epithelial and mesangial cells. LDL stimulates DNA synthesis and cell proliferation, whereas ox-LDL is cytotoxic and induces apoptosis. In other experiments, the expression of ox-LDL receptor LOX-1, was increased in experimental hypertensive glomerulosclerosis (227). DSS rats, when salt loaded with 0.8% salt, showed evidence of impaired renal function and histologic glomerulosclerotic changes, along with markedly elevated levels of LOX-1. These deleterious effects were ameliorated when these animals were treated with a calcium channel blocker.

Clinically, hyperlipidemia is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases [JNC VII, (36)]. Substantial evidence from both human and animal studies now indicates that reduction of cholesterol levels has beneficial effects on blood-pressure regulation and kidney function. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have been used to reduce cholesterol. Statins have also been proposed to have pleiotropic effects, actions independent of their cholesterol-lowering mechanism. Evidence for non–HMG-CoA effects now includes inhibition of NF-κB, a nuclear transcription factor, decrease in geranylation and translocation of Rac1 to the membrane, and even transcriptional regulation of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits, including Nox4, p22phox, and Nox2 in the kidney (71, 353).

4. Eicosanoids

In addition to LDL and ox-LDL, small lipids such as eicosanoids are implicated in the pathogenesis of glomerular injury and hypertension. COX-derived prostanoids are integral in preserving renal function, vascular fluid homeostasis, and blood pressure. Kidney cortical COX2-derived prostanoids such as PGI2 and PGE2 preserve blood pressure and renal function in the volume-contracted state, whereas medulla-derived prostanoids appear to have an antihypertensive effect in individuals challenged with a high salt diet.

5-LOX-derived leukotrienes are involved in inflammatory glomerular injury. LOX product 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) is associated with pathogenesis of hypertension and may mediate Ang II- and transforming growth factor (TGF-β)–induced mesangial cell abnormalities observed in diabetic kidney disease. P450 hydroxylase–derived 20-HETE is a potent vasoconstrictor and is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension. P450 epoxygenase–derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) have both vasodilator and natriuretic effects. Blockade of EET formation is associated with salt-sensitive hypertension. Ceramide has also been demonstrated to be an important signaling molecule, which is involved in pathogenesis of acute kidney injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion and toxic insults. 8-Isoprostaglandin F2α (8-ISO) is formed nonenzymatically from the attack of the O2·− radical on arachidonic acid and is considered a marker of kidney oxidative stress in vivo (293). These pathways provide compelling targets for pharmacologic intervention in renal redox control of hypertension.

5. High salt

Humans have evolved to function in a low-salt environment. The high-salt content of modern diets contributes to hypertension, and reduction in dietary sodium intake to <2.4 g/day has been shown to reduce the severity of hypertension by 2–8 mm Hg, on average [JNC-VII (36)]. Recent data suggest a more nontraditional role for salt in promoting hypertension. Dobrian et al. (55, 228) demonstrated that salt loading leads to hypertension via NAD(P)H-dependent mechanisms that can also exacerbate renal injury and proteinuria in obese spontaneously hypertensive rats. Salt loading has also been shown to increase oxidative stress and blood pressure when the animals are treated for longer intervals and to induce p47phox and gp91phox in rat kidney cortices (201). Proposed mechanisms include paradoxic mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation of NAD(P)H oxidase and oxidative stress. Another study in DSS rats demonstrated that MR blockade reduced salt-induced hypertension by increasing endothelium-derived relaxing factors, inhibiting RAAS components, and decreasing oxidative stress (9).

6. Cigarette smoke

Smoking is an independent risk factor for hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (350). In a Texas cohort with hypertension but no evidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), smoking was independently associated with worsening of GFR after patients were monitored prospectively (264). Furthermore, in patients with diabetic nephropathy (DN) undergoing therapy with an ACE inhibitor for blood pressure control, smokers had worse plasma creatinine levels after 7 years of follow-up (37). Smoking has been shown to induce oxidative stress (330) and also has been found to be a strong predictor for the extent of endothelial injury in patients with hypertensive kidney injury (350). Subjects who smoke heavily and for a long time, as well as passive smokers, seem to be particularly exposed to endothelial damage.

7. Insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia

Insulin resistance is a prominent feature of the cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) and is the precursor to type 2 diabetes and links between obesity, hypertension, and renal disease (Figs. 4 and 5). The metabolic dysregulation observed in the development of insulin-resistance/hyperinsulinemia is proposed to result from oxidative stress: disruption of phosphatidyl inositol 3–kinase (PI3-kinase) and Akt signaling through serine/threonine phosphorylation, reduced and impaired glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) function (286). Insulin resistance has been shown to induce oxidative stress via generation of excessive superoxide anion/H2O2 and decreased catalase synthesis. This is part of a feed-forward mechanism that results in chronic conditions of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress then leads to modulation of vascular endothelial function, smooth muscle contractility, and organ function (Fig. 5). As described in detail elsewhere, the acute sodium-retaining action of insulin at the level of the kidney is one of the unifying mechanisms that connect insulin resistance with renal redox control of hypertension. Indeed, this mechanism appears to play a role in the development of salt sensitivity. Recent data support that oxidative stress can also be involved in this association, as ROS influence sodium handling in the kidney. In particular, increased free radical generation is suggested to promote primary salt retention. One of the mechanisms possibly involved in this action is the modulation of renal cortical and medullary microcirculation. In isolated renal afferent arterioles, O2·− can lead to vasoconstriction, inhibited by a mimetic of SOD, the enzyme responsible for O2·− degradation. Furthermore, infusion of an SOD inhibitor in the medullary interstitium resulted in vasoconstriction accompanied with decreases in urine flow and sodium excretion, whereas infusion of an SOD mimetic opposed these alterations.

8. eNOS uncoupling

eNOS is responsible for the production of NO, a potent vasodilator with an important role in preserving endothelial function. Superoxide-producing enzymes, such as NAD(P)H oxidase and xanthine oxidase, promote NO degradation as they generate a variety of ROS. For example, in hypercholesterolemic rabbits with impaired endothelial relaxation, NO bioavailability was decreased because of oxidation of NO into vasoinactive nitrates/nitrites, and treatment with SOD reversed endothelial dysfunction (225). Other animal models also demonstrate increased degradation of NO as the cause of endothelial dysfunction and hypertension (192). eNOS is a cytochrome p450 reductase–like enzyme that catalyzes flavin-mediated electron transport from the electron donor NAD(P)H to a prosthetic heme group. eNOS uncoupling is a phenomenon that results when deficiency of l-arginine is present for accepting electrons to form NO; instead, eNOS produces O2·− and H2O2. The enzyme reaction uses tetrahydrobiopterin as a cofactor, deficiency of which also results in the production of O2·− instead of NO (23). In SHRs and DOCA-salt sensitive mice, aortas demonstrated increased O2·−, levels that were normalized by L-NAME or endothelium removal (23, 157). Nitrate tolerance and increased O2·− production was postulated to be due to eNOS uncoupling in long-term nitroglycerin treatment of rat aortic rings (226). Last, supplementation of BH4 to insulin-resistant rats and chronic smokers improved their endothelium-dependent vasodilation, implicating eNOS uncoupling as the culprit mechanism (117, 301). Oxidization of BH4 by peroxynitrite (O2·− + NO) and mutations in enzymes involved in BH4 synthesis have been proposed as mechanisms active in vivo that can contribute to eNOS uncoupling (23).

9. Dopaminergic system (DS)/sympathetic nervous system

Dopamine is produced locally in the proximal tubule cells and, after binding to D1 and D5 receptors, inhibits sodium absorption, thereby promoting natriuresis (381). Downstream signaling is mediated through G-protein subunits that are activated by G protein–coupled receptor kinase type 4 (GRK-4). Activating variants of GRK-4, along with abnormal dopamine production, leads to uncoupling of the receptors from their G-protein effector complexes. Both people with essential hypertension and animal models, including DSS rats and SHRs, have been shown to harbor these variants. Overexpression of GRK-4 in mice contributes to hypertension, probably by allowing the unopposed action of Ang II, whereas GRK-4 blockade ameliorates hypertension in rat genetic models. The dopaminergic system has been extensively reviewed by Zeng et al. (381), and readers are advised to refer to their article for further details.

An extensive body of literature links the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and hypertension (2, 191, 205, 279, 285). NO has been shown to play a central role in offsetting oxidative stress/SNS–mediated increase in arterial pressures (118). The NO-cGMP pathway is known to suppress cardiac norepinephrine (NE) release, and oxidative stress can upset this protective relation. A recent study demonstrated that restoring NO levels via adenovirus-mediated nNOS in SHRs improved cardiac sympathetic neurotransmission and ameliorated hypertension (179). In another recent study in the mesenteric arterial bed from SHRs, NE levels were shown to be increased, whereas neuropeptide Y (NPY) levels were reduced (196). N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) reversed these levels and restored NO modulation of SNS activity, demonstrating the importance of antioxidants in maintenance of redox states and normal vascular function. In the DOCA salt-sensitive rats, NAD(P)H oxidase subunits are differentially regulated in the sympathetic (celiac ganglia) and sensory (dorsal root ganglia) nervous systems. The authors postulate that this may lead to vasomotor imbalances and vasoconstriction in the splanchnic beds (24).

It has been shown that modulation of the SNS through various mechanisms contributes to the control of hypertension. In salt-loaded DSS rats, administration of intracere-broventricular tempol (SOD-mimetic) and DPI reversed increased systemic arterial pressure, SNS activity, and heart rate (73). Furthermore, inhibition of Rac1-derived ROS in nucleus tractus solitarius decreased blood pressure and heart rate in stroke-prone SHRs (236). The antioxidant adrenomedullin was shown to inhibit SNS-induced hypertension in salt-loaded mice (74). Overexpression of inducible NO synthase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla causes hypertension and sympathoexcitation via an increase in oxidative stress (161). Increased ROS in the rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to neural mechanisms of hypertension in stroke-prone SHRs (163). ET-1 was shown to be important in O2·− production in the sympathetic neurons of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, and this was mediated by upregulation of ET (B) receptors (46). Renal sympathetic nerves respond to tempol by ameliorating elevation of high blood pressures in SHRs by decreasing oxidative stress (304). Longterm antioxidant treatment improves sympathetic functions and the β-adrenergic pathway in the SHRs (80). Collectively, these experiments emphasize the role of the SNS in mediating hypertension via dysregulation of redox balances in the neurons and the vasculature.

B. Role of the RAAS in oxidative stress and hypertension

The contribution of the RAAS to redox homeostasis has generated extraordinary interest since the discovery of renin >100 years ago. Initially, renin was discovered in kidney extracts by Tigersted and Bergman in 1898, and its role later was explained by Harry Goldblatt, in 1934 (8). It was not until 1939 that hypertensin was discovered by Braun-Menendez, and later in 1958, it was renamed angiotensin by Braun-Menendez and Page (19, 20). Subsequent experiments, including those done by Sir Arthur Guyton, elucidated the physiologic implications of the RAAS and highlighted the importance of the kidney in blood pressure control (97–104, 151). Several decades of hard work ushered us into the 1980s, when Ang II was established as a potent vasoconstrictor that, when inhibited, would lead to improvements in hypertension. Ang II has other important biologic functions, including growth and neovascularization, regulation of glomerular filtration, and tubular transport.

The role of Ang II in the development of kidneys is supported by evidence from deletion of the angiotensinogen gene in mice (Agt−/−). The consequent defective kidney organogenesis is lethal within 10 days of birth (53, 308). Angiotensinogen is expressed mainly in the kidney tubules of mice by embryonic day 17, and its expression declines shortly after birth. Similarly, mice with targeted mutations in ACE, AT1R genes, and in both renin genes, have nearly identical phenotypes characterized by poor survival to weaning, low blood pressure, and abnormal kidney structure. Their kidneys are thickened with hypercellular arterial walls, interstitial fibrosis, inflammation, papillary atrophy, and tubular dilation. Angiotensinogen-overexpression models (transgenic mice expressing the rat angiotensinogen gene alone in the liver and brain, TGM[rAOGEN]123) and (transgenic mice expressing the human angiotensinogen gene alone and treated with human renin bolus, or double transgenic mice expressing both human renin and human angiotensinogen), manifest hypertension (159, 375, 376). Over-expression of angiotensinogen and elevated levels of Ang II can lead to kidney disease by causing growth, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Ang II classically exerts its effects through AT1R and AT2R binding. AT1R binding has been shown to lead to many of the deleterious effects and vasoconstrictor actions of Ang II. Alternatively, AT2R binding leads to some beneficial effects, including reduction of blood pressure. In addition, many other angiotensin receptor–binding effects of Ang II exist, and it is now widely recognized to have not only endocrine effects but also exocrine, paracrine, and autocrine effects. Ligand-receptor binding also leads to G protein versus non–G protein–mediated effects. G protein–mediated effects may be mediated through phospholipase C with formation of 1,4,5-inositol and DAG, whereas non–G protein–mediated effects are through stimulation of tyrosine kinases. Both of these pathways eventually contribute to activation of components of NAD(P)H oxidase/other metabolic oxidases and generation of O2·− and other free radicals.

Some effects of Ang II are direct; however, a number of profibrotic effects are mediated through stimulation of aldosterone. In addition, aldosterone itself has certain actions that are independent of Ang II stimulation. For example, aldosterone acts through AT1R to mediate vascular oxidative stress by increasing mRNA levels of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase components; this effect was abolished by selective MR antagonism, whereas AT1R blockade and tempol decreased only the p47phox mRNA level but not that of p22phox or gp91phox (122). In the same study, MR antagonism uniformly abrogated aldosterone-mediated stimulation of proinflammatory genes, whereas AT1R blockade and tempol had gene-specific effects. The authors concluded that both Ang II–dependent and Ang II–independent pathways are involved in the mechanisms leading to the development of hypertension, vascular inflammation, and oxidative stress induced by aldosterone.

Last, renin itself has been proposed to have proinflammatory effects through binding to the renin receptor on target tissues. Direct inhibition of renin with aliskerin has been shown to have beneficial effects on blood pressure, inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage (155, 243, 256, 333). A recent study, Aliskiren in the EValuation of PrOteinuria In Diabetes (AVOID) Trial, showed that the addition of a renin inhibitor to an ARB in diabetic and hypertensive patients decreases proteinuria further when compared with an ARB alone (251). However, it remains to be seen whether these benefits are sustained over the longer term [i.e., >6 months (133)].

1. Ang II, ROS, and systemic hypertension

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, evidence for Ang II–mediated ROS production and its role in hypertension began to emerge. Landmark studies demonstrated that O2·− production underlies the pathogenesis of hypertension, and this was attributed primarily to Ang II, whereas other catecholamines failed to stimulate production of ROS (176, 233). Others showed that treatment of rats with Ang II infusions led to increases in ROS production and elevated blood pressure, which was effectively reduced by treatment with SOD, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (363). A direct link was then established between Ang II–impaired vasomotor tone resulting in hypertension and increasing vascular O2·− production via membrane NAD(P)H oxidase activation (261).

2. Ang II stimulation of NAD(P)H oxidase and hypertension

Vascular and renal NAD(P)H oxidase is a multicomponent enzyme complex implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension. In addition, NAD(P)H oxidase requires Rac1/Rac2 and Rap1 for activation in some cellular systems. These activating small-molecular-weight G proteins have been demonstrated in some studies to affect O2·− production and hypertension (115, 240, 355). The vascular and renal NAD(P)H oxidases share several characteristics with the multicomponent enzyme complex, as described in neutrophils in an earlier section (6). The active enzyme complex is composed of one of the Noxs plus or minus p22phox. p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox, or one of their isoforms, completes the subunit architecture. However, organizational and functional differences are found between nonphagocytic and phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase, as illustrated in Table 2, including the perinuclear location of all of the subunits. This facilitates rapid recruitment of subunits to generate ROS for signaling purposes.

In the vasculature, the endothelial as well as adventitial NAD(P)H oxidase is composed of gp91phox (Nox2) and p22phox, as well as p47phox and p67phox and the G protein Rac1 (88, 245). It is now established that NAD(P)H oxidase expressed in endothelial cells is an important source of free oxygen radical generation in the arterial wall (147). In contrast, smooth muscle cells either lack Nox2 or have several orders of magnitude lower expression of this subunit when compared with Nox2 homologues such as Nox1 and Nox4 (174). In vitro studies in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) support Ang II–stimulated Nox1 expression in a protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent fashion (245). Use of PKC inhibitor GF109203X efficiently inhibited PKC activity, decreased Nox1 basal expression, and abrogated Ang II-induced upregulation of Nox1 expression. Anti-sense Nox1 mRNA completely inhibited Ang II-induced O2·− production, supporting a role for Nox1 in redox signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells.

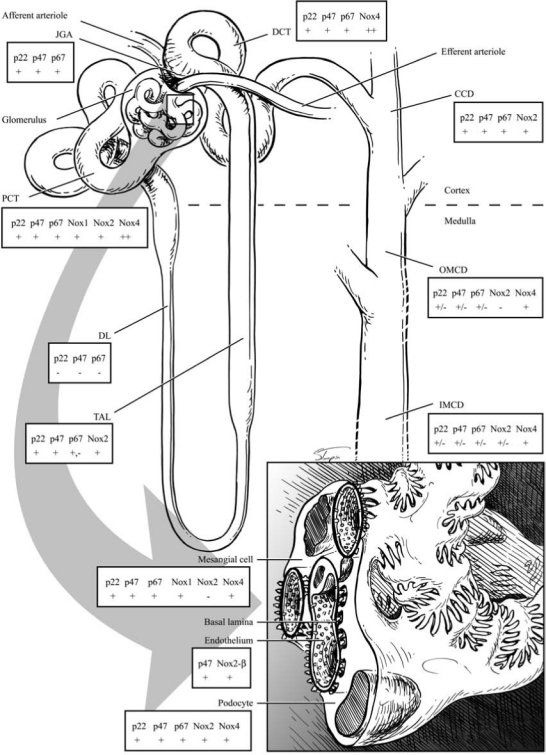

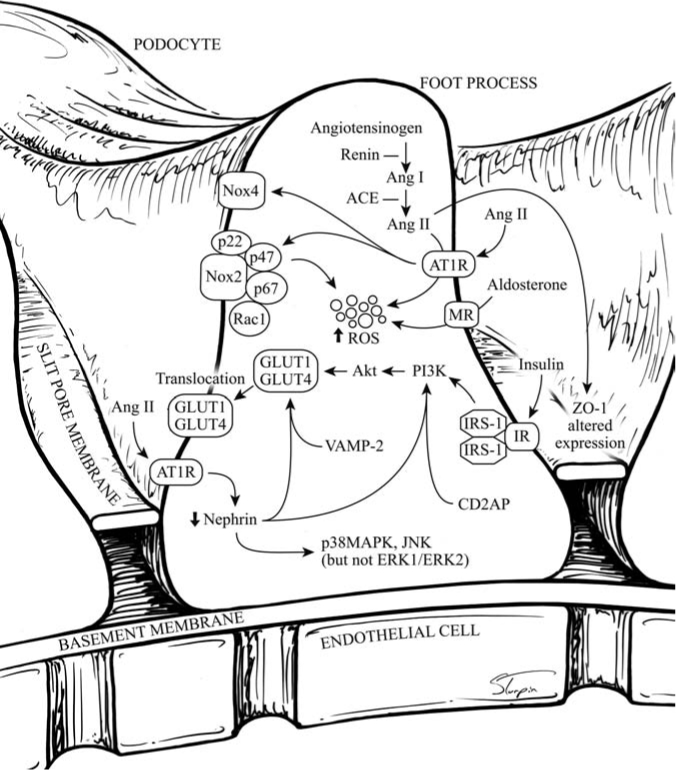

NAD(P)H oxidase, as well as other metabolic oxidases such as xanthine oxidase and mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes (I–IV), are functional in the kidney (278). However, we and others have identified NAD(P)H oxidase–induced ROS production as a primary initiator of oxidative stress within the kidney (183, 353, 355, 356). Various cells in the kidney have now been shown to possess a fully functional NAD(P)H oxidase system, which produces O2·− free radicals under stimulation by cues such as Ang II, agonists that bind to D1-like receptors, and to H+ fluxes (28, 89, 146, 184, 259, 353, 377, 384) (Figs. 6 through 9). Nox4 is expressed at high levels in kidney and other Noxs, including Nox1, Nox2, and Nox-regulatory subunits, are expressed at lower but quantitatively significant levels (4, 78, 146, 214, 244, 259, 303) making Nox enzymes attractive candidates for the origin of renal ROS, including the relatively high levels of H2O2 seen in urine (172). No consensus appears to exist for the corticomedullary differences between the different subunits, as the literature has data from different animals undergoing different treatments. Indeed, a few studies demonstrated no or very little expression of the regulatory subunits in the medulla. However, one report shows that, in SHRs, the expression of Nox1, Nox2, and p67phox is higher in the renal medulla as compared with the cortex, and the expression of Nox4 and p22phox is higher in the cortex than in the medulla (291). Per this group, the expression of p47 is about the same in the cortex versus medulla. The mesangial cells are unique in that they express Nox1, Nox4, and p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox, but not Nox2 (86, 127, 146, 164, 214, 223, 371, 380) (Fig. 6). This may be biologically important, as some data support the fact that mesangial cells may be similar to VSMCs, which also lack Nox2 (expressed at very low levels) (Stockand et al.). In mesangial cells, NO inhibits the expression of Nox1, suggesting cross-talk between NO and O2·−-generating systems (244). p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox are all expressed in the PCT, DCT, CCD, and the macula densa cells (12, 72, 107, 139, 148, 342, 366) (Fig. 6). Nox2 expression has been shown in the PCT and CCD; Nox4, in the PCT and DCT; whereas Nox1 expression is confined to the PCT, once again demonstrating differential regulation of redox control within the cortex. In situ hybridization experiments initially localized Nox4 mRNA expression to the renal cortex, whereas the medulla showed much lower expression (244, 303). However, immunohistochemical studies also demonstrate Nox4 expression in distal portions of the human nephron, and Nox4 mRNA has been demonstrated in medullary collecting ducts (244, 303). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the data for Nox4 were obtained from different animal groups. The Nox4 isoform of NAD(P)H oxidase is unique in that it also can use NADH as the substrate for generating O2·− (173). This may be relevant to the kidneys, as the cortex and outer medulla preferentially use NADH as a substrate and express Nox4 at high levels in these regions (387).

FIG. 6.

NADPH oxidase isoform and subunit expression in the nephron. JGA, juxtaglomerular apparatus; PCT, proximal convoluted tubule; DL, descending limb; TAL, thick ascending limb; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; CCD, cortical collecting duct; OMCD, outer medulla collecting duct; IMCD, inner medulla collecting duct; ++, high expression; +, expression; −, no expression.

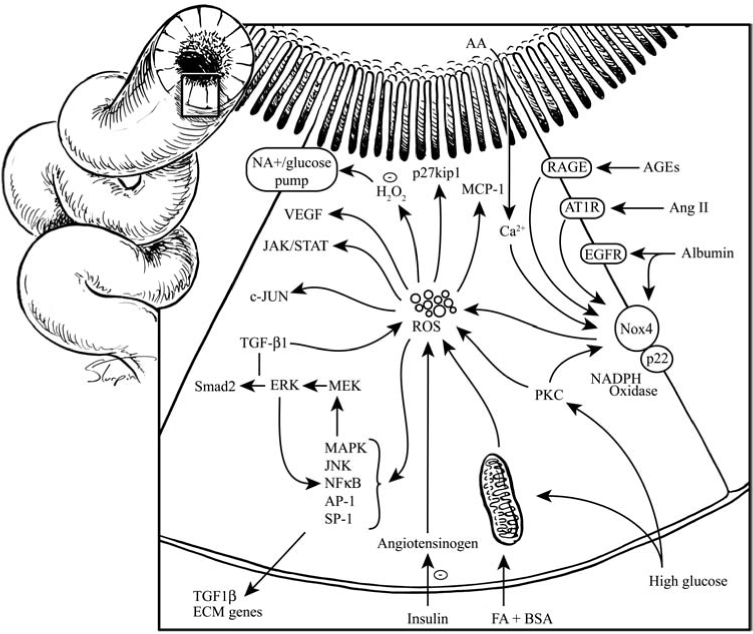

FIG. 9.

Schematic representation of known redox pathways within the proximal tubule cells. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; FA-BSA, free fatty acid-linked bovine serum albumin; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; ECM, extracellular matrix; Smad2, small mothers against decapentaplegic homologue 2. These are transcription factors and regulators of TGF-β ligands. For other abbreviations, see other figure legends and abbreviations page.

The main physiologic function of Nox4 is largely unknown. Nox4 may serve varying roles, depending on the tissue where it is expressed and its function as an ROS producer. The expression pattern of Nox4 in the kidney is consistent with several renal-specific functions. For example, by virtue of close proximity to EPO expression, Nox4 might regulate EPO production in the kidney. The major site for EPO synthesis in adults is generally believed to be the peritubular fibroblast-like cells, although EPO receptors have been demonstrated in mesangial cells, PTCs, and the glomerulus (208, 238, 297). As mentioned before, EPO synthesis is ramped up in response to hypoxia (with proline hydroxylases as main sensors) and anemia. Interestingly, recent observations suggest that Nox4 may regulate EPO synthesis through HIF-dependent pathways [hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α)] and HIF-independent pathways (H2O2-sensitive target GATA-2) (131; 202). Finally, SOD3, which is expressed in PTC, has been proposed to play a role in EPO production (314).

Another putative functional role in host defense has been proposed in the kidney for Nox4, by virtue of expression in the inner medulla, which is known to be a hypoxic environment (244). ROS produced by Nox4 could potentially have microbicidal effects on the urine, and this is supported by evidence of high H2O2 in the urine (338).

Most important, Nox4 is integral in the development of the renal complications of insulin resistance and hypertension. Increased expression of Nox4 and p22phox and accumulation of 8-hydroydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), marker for ROS-induced DNA damage, in the kidney of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats was reversed after treatment with insulin for 2 weeks (63). Another group working with the same animal model showed that infusing antisense oligonucleotides for 2 weeks, targeting Nox4 mRNA, was effective in reducing ROS in cortical and glomerular homogenates, organelle hypertrophy, and fibronectin expression, which are characteristic markers of diabetic kidney disease. One putative pathway proposed to increase Nox4 expression has been the Rho/Rho-kinase pathway, and this was inhibited by administration of fasudil (Rho-kinase inhibitor) and statins (81). Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] attenuated Nox4 expression, decreased NAD(P)H oxidase activity, and improved proteinuria in streptozotocin-treated SHRs (diabetic SHRs) (14). These data suggest a signaling role for Nox4-derived ROS in the development of diabetic kidney disease (84). We now discuss the role of each subunit as it relates to Ang II–mediated hypertension.

a. p22phox and hypertension

One of the first subunits to be implicated in redox control of hypertension was p22phox. This 22-kDa protein was initially thought to be confined to the plasma membranes of cells; however, data now show that p22phox, along with Nox2, may localize to the perinuclear area (181). Expression of p22phox mRNA was reported to increase in Ang II–infused hypertensive rats (75). Impaired endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation observed in this animal model was reversed in part by increasing vascular SOD levels, suggesting a crucial role for vascular (O2·−) in endothelial dysfunction. Additionally, a polymorphism of p22phox, which alters an amino acid in the potential heme-binding sites, has been demonstrated to be more frequent in control subjects compared with patients with coronary artery disease (135). Overexpression of p22phox, selectively in smooth muscle of transgenic (Tg) mice [Tg(p22smc)], potentiated Ang II–induced hypertrophy of the aorta and led to hypertension (346). Interestingly, mice not stimulated with Ang II did not manifest either increases in aortic-wall thickness or blood pressure, emphasizing the importance of the stimulated enzyme in hypertension when compared with the role of constitutive enzyme in normal processes, such as cellular signaling. Further, overexpression of p22phox led to chronic oxidative stress caused by excessive H2O2 production (175). This evoked a compensatory response involving increased eNOS expression and NO production. NO in turn increased eSOD protein expression and counterbalanced increased ROS production, leading to the maintenance of normal vascular function and hemodynamics. So far, p22phox-specific inhibitors are not available; however, siRNA induced knockdown of p22phox gene expression in SD rats, led to decrease in renal NAD(P)H oxidase activity, expression of Nox proteins and oxidative stress, and a slight decrease in blood pressure during an Ang II slow-pressor response (217). With the recent identification of a naturally existing p22phox knockout mouse (nmf333 mouse strain), the contribution of this subunit to redox regulation of blood pressure can be studied (232). Collectively, these reports support the hypothesis that the alteration of p22phox expression might modulate ROS levels in the vasculature and influence the progression of vascular diseases (203).

b. gp91phox (Nox2) and hypertension

gp91phox (Nox2) was among the first to be discovered to cause a phagocytic burst to kill engulfed bacteria. The expression of nonphagocytic gp91phox, as described earlier, is confined to the endothelial cells and adventitia of the blood vessels; surprisingly, it is not detected in the VSMCs of large arteries; however, its isoform Nox2 is expressed in the VSMCs (173, 174, 312). In contrast, gp91phox expression was knocked down by antisense oligos in resistance arteries from humans, and this led to abrogation of ROS production, whereas Nox1 expression was not detected here (327). The role of gp91phox (Nox2) in hypertension was described by Morawietz et al. (219), who showed that tenfold-elevated mRNA levels in the aorta were associated with threefold elevated levels of O2·− anion production in stroke-prone SHRs (SHR15) (219). In SHR15 rats, a decreased response to ACh, NO-donor (S-nitroso-N-acetyl-d, l-penicillamine), and organic nitrate (glyceryl trinitrate) was found, compared with an age-matched wild-type control, Wistar rats (WIS15). NO stimulates soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and sGC β(1)-subunit proteins (heterodimers), which are involved in the formation of cGMP, which is an important vasodilator. Expression of guanylate cyclase enzyme complex was downregulated in both aorta and lungs of SHR15. This article was among the first to suggest that hypertension is a manifestation of an imbalance between excess vascular ROS and an impaired NO signal-transduction pathway. In another model of hypertension, Ang II–infused SD rats, gp91phox expression was increased threefold at both mRNA and protein levels when the infusion was continued for 1 week. They also showed that NAD(P)H oxidase–induced superoxide production may trigger NOS III uncoupling, leading to impaired NO/cGMP signaling and to endothelial dysfunction in this animal model. However, as noted earlier, gp91phox has been documented to be absent in VSMCs from large arteries but present in resistance arteries in humans.

c. p47phox and hypertension