Abstract

Recognition of a pivotal role for eicosanoids in both normal and pathologic fibroproliferation is long overdue. These lipid mediators have the ability to regulate all cell types and nearly all pathways relevant to fibrotic lung disorders. Abnormal fibroproliferation is characterized by an excess of pro-fibrotic leukotrienes and a deficiency of anti-fibrotic prostaglandins. The relevance of an eicosanoid imbalance is pertinent to diseases involving the parenchymal, airway, and vascular compartments of the lung, and is supported by studies in both humans and animal models. Given the lack of effective alternatives and the existing and emerging options for therapeutic targeting of eicosanoids, such treatments are ready for prime time.

Keywords: Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, Pulmonary fibrosis, Airway remodeling

As a result of both research advances and therapeutic disappointments over the past 20 years, favored concepts regarding the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis have shifted from a central focus on inflammation to one of abnormal fibroproliferative responses to lung injury which result in tissue remodeling.1 Such responses are thought to involve apoptotic loss of alveolar epithelial cells; recruitment, expansion, and activation of mesenchymal cells; and deposition of excess matrix proteins such as collagen, particularly by α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts. These processes in turn are driven by a pro-fibrotic milieu that is characterized by oxidant stress, growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), Th2-type immune response polarization, and abnormalities in the coagulation cascade.1 Although the prototypic fibroproliferative lung diseases are diffuse disorders of the pulmonary parenchyma such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), many aspects of their pathobiology are shared by remodeling diseases involving other compartments of the lung. Examples include airway remodeling in asthma and in bronchiolitis obliterans, and vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Unfortunately, advances in the understanding of the pathobiology of IPF have not yet been translated into effective therapies, and its prognosis remains exceedingly poor.2

This review focuses on one particular class of mediators that has been implicated in fibrotic lung disorders – namely, eicosanoid metabolites of arachidonic acid which include leukotrienes (LTs) and prostaglandins (PGs). Because of either unawareness or bias on the part of investigators and thought leaders, the participation of eicosanoids is certainly underappreciated and often entirely unmentioned in review articles or scientific symposia concerning fibrogenesis. Three features of eicosanoids in this context deserve attention and will be emphasized here: 1) remodeling disorders of the lung are characterized by an imbalance favoring pro-fibrotic LTs over anti-fibrotic PGs; 2) the eicosanoid imbalance hypothesis provides a framework which integrates and helps to explain the effects of many other mediators and modifying influences; and 3) therapeutic targeting of eicosanoids, already well-established in diseases such as asthma and pulmonary hypertension and rapidly advancing in sophistication, provides opportunities for application to fibrotic lung disease.

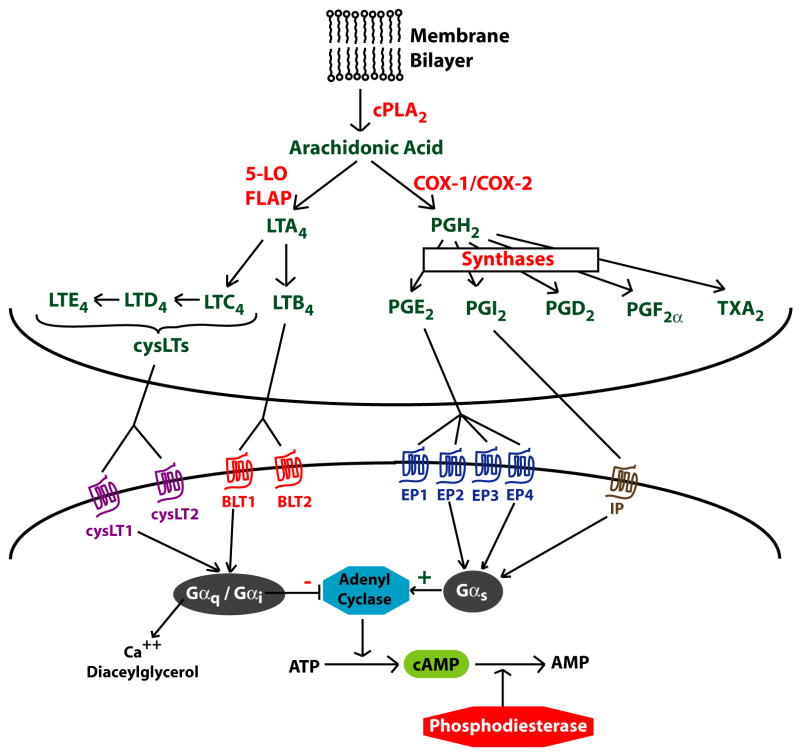

Eicosanoids: synthesis and cellular effects

Eicosanoids are a group of lipid mediators derived from the 20-carbon fatty acid arachidonic acid (eicosa = 20 in Greek). After release from membrane phospholipids by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (Fig 1), arachidonate is further metabolized by the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) pathway into LTs, or by the cyclooxygenase (COX)-1/2 pathway into PGs.3 LTs include both LTB4 and the cysteinyl LTs (cysLTs) C4, D4, and E4, and are synthesized mainly by leukocytes. PGs, including PGE2, PGI2, PGD2, PGF2α, and thromboxane A2, are synthesized by both leukocytes and structural cells. Individual cell types generate specific profiles of eicosanoids that reflect their complement of terminal synthase enzymes. LTs and PGs exert a myriad of actions that contribute to both homeostasis and disease. Eicosanoids act in a paracrine or autocrine fashion by ligating specific 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors. These receptors signal via changes in intracellular cAMP, calcium, or diacylglycerol depending on the type of associated G protein. Though best known for their role in pain, fever, and inflammatory disorders such as asthma and arthritis, a substantial body of research has shown that they modulate pulmonary fibroproliferative responses as well.4 Eicosanoids can affect the fibroproliferative response via both direct actions on structural cells and indirectly by modulating inflammatory cells, mediators, and other pathways important in pulmonary fibrosis.

Fig 1. Eicosanoid synthesis and receptors.

Arachidonic acid, released from membrane phospholipids by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), can be metabolized by the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) pathway to make leukotrienes (LT) or by the cyclooxygenase pathway (COX) to make prostaglandins (PG). Terminal synthases complete the biosynthesis of specific eicosanoid products. Eicosanoids exert their actions via binding to 7-transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors and subsequent intracellular signaling. FLAP = 5-LO activating protein.

As summarized in Table 1, eicosanoids can influence the behavior of all of the cell types relevant to pulmonary fibrosis, including leukocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells, and mesenchymal cells. LTs are well known to promote leukocyte accumulation by increasing their generation in the bone marrow, their extravasation into tissues, and their survival at sites of inflammation.5 They also activate macrophages to release other pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, and growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor.4 CysLTs stimulate epithelial cells to produce the pro-fibrotic mediator, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β),6 and endothelial cells to release pro-inflammatory chemokines (CXCL2 and IL-8).7 LTs are also known to stimulate fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and myofibroblast differentiation.8 CysLTs promote the proliferation of murine and human bone marrow-derived fibrocytes, which participate in tissue remodeling and repair.9

Table 1.

Cellular Responses to Eicosanoids

| Cell types and actions | LT effects | PG effects |

|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | ||

| Chemotaxis | ↑ | ↓ |

| Adhesion | ↑ | ↓ |

| Myelopoiesis | ↑ | ↓ |

| Th2 response | ↑ | ↓ |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokine release | ↑ | ↓ |

| Reactive O 2 species | ↑ | ↓ |

| Epithelial cells | ||

| Survival | ↓ | ↑ |

| TGF- β release | ↑ | ? |

| Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition | ? | ↓ |

| Fibroblasts | ||

| Chemotaxis | ↑ | ↓ |

| Proliferation | ↑ | ↓ |

| Collagen synthesis | ↑ | ↓ |

| Collagen crosslinking | ? | ↓ |

| Collagen degradation | ? | ↑ |

| Myofibroblast differentiation | ↑ | ↓ |

| Matrix contraction | ? | ↓ |

| Fibrocyte proliferation | ↑ | ? |

| Epithelial survival factors | ? | ↑ |

|

| ||

| Net effects | “pro-fibrotic” | “anti-fibrotic” |

Despite their reputation as “pro-inflammatory” mediators in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, the actions of PGE2 – the major prostanoid product of epithelial cells and fibroblasts –in other contexts may oppose inflammation and fibrogenesis. In contrast to LTs, PGE2 inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis.10 PGE2 enhances epithelial survival and migration, which are important in resolving lung injury.11 It also is a potent inhibitor of fibroblast activation, including migration, proliferation, collagen synthesis, and myofibroblast differentiation.12,13 PGE2 furthermore increases fibroblast collagen degradation14, decreases lysyl oxidase production which leads to decreased collagen crosslinking15, and inhibits fibroblast-mediated extracellular matrix contraction.16 PGI2 tends to have similar anti-fibrotic effects. PGE2 has been shown to attenuate the ability of TGF-β to induce myofibroblast differentiation as well as synthesis of collagen17 and connective tissue growth factor in fibroblasts. TGF-β can induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, an additional potential source of fibroblasts in the lung and other organs. PGE2 has been reported to inhibit this process in renal epithelial cells.18

These down-regulatory effects of PGs on fibroblasts, which also extend to other mesenchymal cells such as smooth muscle cells, are typically mediated by cyclic AMP-coupled E prostanoid (EP) and I prostanoid (IP) receptors. Together, these data support predominant “pro-fibrotic” effects of LTs and “anti-fibrotic” effects of PGE2 (and PGI2).

The impact of these in vitro actions is supported by in vivo animal studies. Mice deficient in 5-LO, which are unable to synthesize LTs and have undetectable levels in lung lavage fluid, have less severe fibrosis after treatment with bleomycin than do wild type mice.19 Targeted disruption of LTC4 synthase, the terminal enzyme for cysLT biosynthesis, also provided significant protection against fibrosis in this model.20 Protection against bleomycin fibrosis was also observed with administration of a 5-LO inhibitor and a cysLT1 antagonist.21 By contrast, bleomycin-induced fibrosis was worse in COX-2 deficient mice22 and in animals treated with the COX inhibitor indomethacin23, and was attenuated by administration of a PGI2 analog.24

The leukotriene/prostaglandin imbalance: a paradigm for pulmonary fibrosis

Additional evidence supporting a critical role for eicosanoids in fibrotic lung disease derives from observations that human and animal models of pulmonary fibrosis exhibit a synthetic imbalance favoring pro-fibrotic LTs over anti-fibrotic PGE2.

Lavage fluid from patients with IPF contains lower levels of PGE2 than does fluid from normal controls.25 Fibroblasts grown from lung tissue of patients with IPF synthesize less PGE2 than do cells from normal controls due to diminished COX-2 expression.26–28 This has important pathologic consequences, as the decrease in COX-2 and PGE2 in these cells was shown to contribute to the enhanced collagen synthesis and cell proliferation in response to TGF-β.28 On the other hand, lavage fluid from patients with IPF contains higher levels of LTB4 than in controls.29 Lung tissue homogenates from patients with IPF have 15-fold higher levels of LTB4 and 5-fold higher levels of LTC4 than controls, reflecting constitutive activation of the 5-LO enzyme in alveolar macrophages.30 Increased lung LT levels have also been observed in mice19 after intratracheal administration of bleomycin, a commonly used animal model of pulmonary fibrosis.

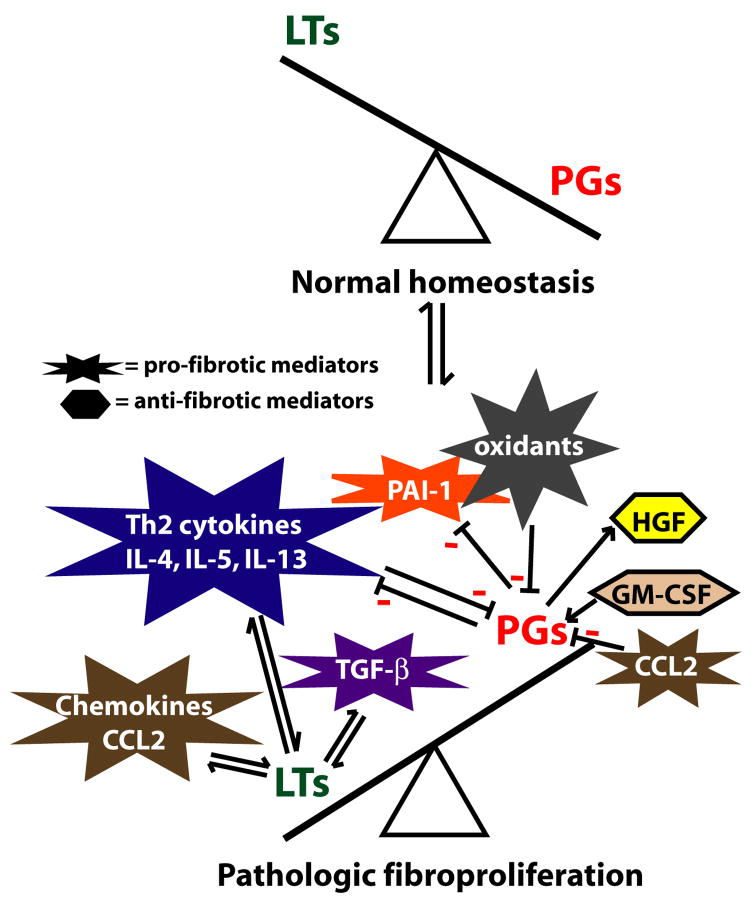

Cross-talk between eicosanoids and other mediators of fibrosis

Eicosanoids and many other classes of mediators, including cytokines, modulate the generation of each other, and it is likely that such crosstalk is central to the influence of both classes of molecules on fibrogenesis (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Crosstalk between eicosanoids and other mediators.

During normal homeostatic conditions, lung levels of PGs exceed LT levels. However, abnormal fibroproliferation is characterized by a synthetic imbalance favoring LTs over PGs. Moreover, other mediators known to play important roles in modulating fibrogenesis can regulate, or be regulated, by LTs or PGs. Arrows indicate stimulatory effects and minus signs indicate inhibitory effects.

Certain of the potent pro-fibrotic effects of CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), a chemokine known to promote fibrosis through its ability to recruit fibrocytes, increase extracellular matrix, and abrogate the ability of epithelial cells to inhibit fibroblast proliferation, are mediated by a decrease in PGE2 synthesis.31 On the other hand, the anti-fibrotic cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is able to decrease fibroblast proliferation by upregulating PGE2 synthesis.32 PGE2 has also been shown to induce the synthesis of hepatocyte growth factor, an anti-fibrotic mediator that enhances epithelial cell survival and whose deficiency in fibroblasts of patients with IPF was overcome by exogenous PGE2.33 TGF-β stimulates LT synthesis34, while the 5-LO pathway is required for optimal stimulation and activation of TGFβ.35

An imbalance favoring elaboration of Th2 over Th1 cytokines is a key feature of pulmonary fibrosis. Interestingly, eicosanoids can influence this balance and their synthesis/actions are influenced by it. Both LTB4 and cysLTs have been shown to promote a polarized Th2 response in T cells, augmenting synthesis of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.5 While PGE2 favors Th2 responses in vitro, mounting evidence suggests the opposite effect in the lung in vivo.36 Both IL-4 and IL-13 down-regulate PGE2 production by inhibiting COX-2 induction37, while promoting the expression of LT biosynthetic enzymes and cysLT1 receptor.38

Eicosanoids also interact with several other pathways important in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Oxidant stress has been implicated in promoting fibrogenesis, and iloprost, a prostacyclin analog, has been shown to have antioxidant effects.39 The antioxidant molecule glutathione, whose levels in lung lavage fluid are reduced in IPF, is required for PGE2 synthesis. The plasminogen activation system has been shown to be dysregulated in pulmonary fibrosis, and PGE2 has been reported to inhibit expression of the key pro-fibrotic molecule, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.40 Prostaglandin-induced elevations in cAMP have also been shown to upregulate matrix metalloproteinases41, which play an anti-fibrotic role in pulmonary fibrosis. The extensive cross-talk between eicosanoids and other mediators provides a framework for better understanding the potential mechanisms by which each influence pulmonary fibroproliferative responses.

Role of eicosanoids in other types of remodeling disorders of the lung

The potential role of eicosanoids in pulmonary parenchymal fibrosis is not limited to IPF. Increased levels of LTs in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid have been noted in patients with scleroderma lung disease42 and pigeon breeder’s lung.43 Increased generation of LTs has also been shown in alveolar macrophages from patients with asbestosis.44

Airway remodeling in asthma refers to structural changes including epithelial injury, smooth muscle cell accumulation, and subepithelial fibrosis. These are thought to contribute to airflow obstruction and hyperreactivity observed in chronic asthma. Beyond their well-known role in the inflammatory component of asthma, LTs may also contribute to airway remodeling. They can induce proliferation of bronchial smooth muscle cells as well as fibroblasts.6 In a mouse model of chronic allergic asthma, cysLT1 antagonists have been shown to not only prevent airway remodeling, but also to reverse established remodeling.45 A cysLT1 antagonist has also been shown to reduce the accumulation of airway wall myofibroblasts following allergen challenge in humans.46 In addition, bronchial fibroblasts from patients with severe asthma have been shown to have impaired PGE2 production.47

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is characterized by vascular intimal proliferation, medial hypertrophy, and vascular fibrosis. PGI2 deficiency is a central feature in the pathogenesis of this disorder, and exogenously administered PGI2 analogs are considered standard therapy. Although such agents were originally employed for their vasodilator properties, they are now appreciated to also limit vascular remodeling.48 Moreover, a role for LT overproduction in pulmonary hypertension is also supported by studies in patients and animals. It is therefore apparent that an imbalance of eicosanoids is a paradigm common to remodeling disorders affecting parenchymal, airway, and vascular compartments of the lung.

Eicosanoids as therapeutic targets

As noted, PGI2 analogs as well as 5-LO inhibitors and cysLT receptor antagonists are already used for pulmonary hypertension and asthma, respectively. Although both of these disorders are characterized by tissue remodeling, as discussed above, these therapeutic approaches were of course not originally undertaken to ameliorate or prevent fibroproliferation. Given the multiple lines of evidence which have emerged to support a central role of eicosanoids in tissue remodeling, however, it is now rational to therapeutically target eicosanoids with an explicit goal of attenuating fibroproliferative responses. With such a goal in mind, collateral benefits from this approach – such as smooth muscle relaxation and suppression of inflammatory/immune activation – are desirable but of secondary importance. Unlike biological therapies against peptide mediators such as chemokines or growth factors, which are still in early stage development, already existing anti-LT drugs and PGs for administration have known properties, acceptable safety profiles, and reasonable costs. Moreover, newer strategies to block LTs or to administer PG analogs are advancing rapidly as a result of interest in developing better therapeutics not only for pulmonary conditions but for diseases such as atherosclerosis and osteoporosis. Here we will discuss certain aspects of therapeutic targeting of pulmonary fibroproliferative disorders from an “eicosanoid-centric” perspective.

More than 20 years ago, the first generation lipoxygenase inhibitor, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, was shown to inhibit bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.49 Since this drug not only inhibits lipoxygenases other than the 5-LO but also possesses generalized anti-oxidant activity, this study did not specifically establish a potential for LT targeting. Since then, however, bleomycin-induced fibrosis in mice has been shown to be attenuated by both the specific 5-LO inhibitor zileuton21 as well as the cysLT1 antagonist montelukast50, and dramatic effects of montelukast to prevent and reverse45 airway remodeling in a mouse model of chronic allergic asthma have been observed. Zileuton has been explored in a single-center study for the treatment of IPF, and the results are pending. New generation LT receptor antagonists as well as inhibitors of LT biosynthesis which target 5-LO, 5-LO activating protein, LTA4 hydrolase, and LTC4 synthase are currently under development, so it is likely that the available options for more potently and specifically targeting these mediators will continue to expand over the next decade. In order for anti-LT therapy to be intelligently applied in patients with fibrotic lung disease, remaining questions regarding the relative importance of cysLT1 vs. cysLT220 and of LTB4 vs. cysLTs30 in human pulmonary fibrosis need to be answered.

Given the diverse and potent anti-fibrotic effects of PGs, therapeutic approaches to administer them directly or to increase their synthesis can also be envisioned. As the most abundant prostanoid product of alveolar epithelial cells and fibroblasts, the one whose anti-fibrotic actions have been most extensively investigated, and whose deficiency has been established in fibrotic lung disease, PGE2 administration is attractive. This approach would thus parallel that of administering PGI2 analogs to pulmonary hypertension patients who are known to be deficient in endothelial synthesis of this prostanoid. In fact, short-term administration of aerosolized PGE2 has been performed in humans with IPF and has been shown to augment deficient lung lavage PGE2 levels to those of normal subjects25; no functional effects or longer-term administration were examined, however. In subjects with asthma, inhaled PGE2 has been shown to elicit bronchodilation and to protect against induced bronchoconstriction as well as airway inflammation.51 A practical limitation of PGE2 inhalation is that this elicits cough in some patients. It is possible that this side effect could be overcome by selective EP targeting if the PGE2 receptor which mediates most anti-fibrotic effects (EP2) does not mediate cough, but this remains to be determined. Another potential hurdle was raised by a recent study demonstrating that fibroblasts from some patients with IPF are resistant to the anti-fibrotic actions of PGE2, owing to down-regulation of EP2;52 it remains to be determined if this translates into in vivo resistance to PGE2. Since PGI2 via IP signaling shares with EP2 the ability to activate adenyl cyclase to produce cAMP and to inhibit fibroblast activation, and IP responsiveness seemed to be preserved in EP2-deficient IPF fibroblast lines, administration of PGI2 analogs might circumvent this concern. Although in pulmonary hypertension these drugs are administered either via continuous intravenous infusion or by very frequent (6–9 times daily) inhalation, the need for such arduous dosing reflects the transient nature of their vasodilatory actions. With an alternative goal of inhibiting fibroproliferative events that undoubtedly involve cAMP modulation of gene expression, it seems likely that less frequent PG administration regimens may be feasible, but these will require examination in animal models. Preliminary results from a small 6-week trial of 6 to 9 daily doses of inhaled iloprost in patients with IPF and pulmonary hypertension failed to demonstrate improvement in walk distance, dyspnea, or oxygenation53; however, this study was certainly not designed to detect changes in the extent or progression of pulmonary fibrosis and should not deter properly designed studies to directly explore this question.

It is also instructive to consider the effects of current or candidate anti-inflammatory/anti-fibrotic therapies on eicosanoid production and the possibility that such effects may have ramifications for pulmonary fibrogenesis. As many connective tissue diseases are associated with increased risk of pulmonary fibrosis, nonsteroidal agents for pain or inflammatory arthritis should be used with caution since they inhibit PG synthesis and, at least in animal models, promote pulmonary fibrosis. No clinical data definitively address whether such a correlation exists in patients. Efforts to determine this are undoubtedly confounded by the varying dosages and durations of therapy with these agents, their availability as over-the-counter medicines, and the difficulties patients may have recalling their usage. However, a controlled study to answer this question may have important implications. Corticosteroids are still used to treat IPF in some instances, but have proven to have very limited efficacy. Likewise, the ability of inhaled corticosteroids to ameliorate airway remodeling in asthma has similarly been disappointing. It is at least possible that the lack of anti-fibrotic efficacy of corticosteroids is in part related to their ability to limit PGE2 synthesis by potently inhibiting transcriptional induction of both COX-2 and PGE synthase.54 At the same time, they are often ineffective at inhibiting LT synthesis.4 By exacerbating the existing LT-PG imbalance in fibrotic diseases, corticosteroids may actually worsen fibrosis. Interestingly, certain other therapeutic approaches have the potential to enhance PGE2 biosynthesis. One example is antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine; by augmenting glutathione levels, this agent may increase PGE2 production since the terminal PGE synthase enzyme is glutathione-dependent. Additionally, the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan has been shown to attenuate bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, and this was associated with its ability to increase PGE2 synthesis.55

As cAMP signaling mediates the direct inhibitory effects of PGs on fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, advances in PG analog development may yield synergies with other lines of drug development. One example is phosphodiesterase inhibitors, which block cyclic nucleotide degradation and can thereby exert anti-fibrotic effects similar to PGE2. In fact, synergistic benefits on vascular remodeling were observed when iloprost was combined with a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.56

Conclusion

Eicosanoids have been shown to influence nearly all of the pathobiological aspects of pulmonary fibroproliferation. They can directly influence inflammatory cells, alveolar epithelial cells, and mesenchymal cells, and exert indirect effects by modulating a multitude of peptide mediators, chemokines, and other relevant pathways. Accumulating evidence supports a paradigm of eicosanoid imbalance in which human fibrotic lung disorders are characterized by an excess of pro-fibrotic leukotrienes, a deficiency of anti-fibrotic PGs, or both. Animal studies have provided support for the in vivo importance of this imbalance. Potential therapies can be designed to address this imbalance, and may include the inhibition of LT synthesis or actions and the administration of prostanoids. Agents that promote the anti-fibrotic downstream signaling effects of prostanoids, such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors, hold additional promise. While clinical trials are of course needed to explore and optimize these potential therapies, the potential of eicosanoid targeting is evident.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at the University of Michigan and funded by NIH P50 HL56402 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. SKH was supported by NIH T32 HL07749.

Abbreviation List

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- PG

prostaglandin

- LT

leukotriene

- cysLT

cysteinyl leukotriene

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- 5-LO

5-lipoxygenase

- EP

E prostanoid receptor

- IP

I prostanoid receptor

- cysLT1

cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1

- cysLT2

cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2

Footnotes

Dr. Peters-Golden declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Huang declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charbeneau RP, Peters-Golden M. Eicosanoids: mediators and therapeutic targets in fibrotic lung disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108:479–491. doi: 10.1042/CS20050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosse Y, Thompson C, McMahon S, et al. Leukotriene D4-induced, epithelial cell-derived transforming growth factor beta1 in human bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzonyi B, Lotzer K, Jahn S, et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor and protease-activated receptor 1 activate strongly correlated early genes in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6326–6331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601223103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phan SH, McGarry BM, Loeffler KM, et al. Leukotriene C4 binds to rat lung fibroblasts and stimulates collagen synthesis. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot Res. 1987;17B:997–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannella KM, McMillan TR, Charbeneau RP, et al. Cysteinyl leukotrienes are autocrine and paracrine regulators of fibrocyte function. J Immunol. 2007;179:7883–7890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong RA. Investigation of the inhibitory effects of PGE2 and selective EP agonists on chemotaxis of human neutrophils. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2903–2908. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savla U, Appel HJ, Sporn PH, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) regulates wound closure in airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L421–431. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine A, Poliks CF, Donahue LP, et al. The differential effect of prostaglandin E2 on transforming growth factor-beta and insulin-induced collagen formation in lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16988–16991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White ES, Atrasz RG, Dickie EG, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) inhibits fibroblast migration by E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in PTEN activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:135–141. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum BJ, Moss J, Breul SD, et al. Effect of cyclic AMP on the intracellular degradation of newly synthesized collagen. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:2843–2847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choung J, Taylor L, Thomas K, et al. Role of EP2 receptors and cAMP in prostaglandin E2 regulated expression of type I collagen alpha1, lysyl oxidase, and cyclooxygenase-1 genes in human embryo lung fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 1998;71:254–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skold CM, Liu XD, Zhu YK, et al. Glucocorticoids augment fibroblast-mediated contraction of collagen gels by inhibition of endogenous PGE production. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111:249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.99269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas PE, Peters-Golden M, White ES, et al. PGE(2) inhibition of TGF-beta1-induced myofibroblast differentiation is Smad-independent but involves cell shape and adhesion-dependent signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L417–428. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00489.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A, Wang MH, Dong Z, et al. Prostaglandin E2 is a potent inhibitor of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: interaction with hepatocyte growth factor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1323–1331. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00480.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters-Golden M, Bailie M, Marshall T, et al. Protection from pulmonary fibrosis in leukotriene-deficient mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:229–235. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.2104050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beller TC, Friend DS, Maekawa A, et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor controls the severity of chronic pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400235101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Failla M, Genovese T, Mazzon E, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of leukotrienes in an animal model of bleomycin-induced acute lung injury. Respir Res. 2006;7:137. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodges RJ, Jenkins RG, Wheeler-Jones CP, et al. Severity of lung injury in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice is dependent on reduced prostaglandin E(2) production. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1663–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63423-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore BB, Coffey MJ, Christensen P, et al. GM-CSF regulates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via a prostaglandin-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;165:4032–4039. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami S, Nagaya N, Itoh T, et al. Prostacyclin agonist with thromboxane synthase inhibitory activity (ONO-1301) attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L59–65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00042.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borok Z, Gillissen A, Buhl R, et al. Augmentation of functional prostaglandin E levels on the respiratory epithelial surface by aerosol administration of prostaglandin E. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1080–1084. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilborn J, Crofford LJ, Burdick MD, et al. Cultured lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a diminished capacity to synthesize prostaglandin E2 and to express cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1861–1868. doi: 10.1172/JCI117866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vancheri C, Sortino MA, Tomaselli V, et al. Different expression of TNF-alpha receptors and prostaglandin E(2)Production in normal and fibrotic lung fibroblasts: potential implications for the evolution of the inflammatory process. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:628–634. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.5.3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keerthisingam CB, Jenkins RG, Harrison NK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency results in a loss of the anti-proliferative response to transforming growth factor-beta in human fibrotic lung fibroblasts and promotes bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1411–1422. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wardlaw AJ, Hay H, Cromwell O, et al. Leukotrienes, LTC4 and LTB4, in bronchoalveolar lavage in bronchial asthma and other respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilborn J, Bailie M, Coffey M, et al. Constitutive activation of 5-lipoxygenase in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1827–1836. doi: 10.1172/JCI118612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore BB, Peters-Golden M, Christensen PJ, et al. Alveolar epithelial cell inhibition of fibroblast proliferation is regulated by MCP-1/CCR2 and mediated by PGE2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L342–349. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00168.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charbeneau RP, Christensen PJ, Chrisman CJ, et al. Impaired synthesis of prostaglandin E2 by lung fibroblasts and alveolar epithelial cells from GM-CSF−/− mice: implications for fibroproliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L1103–1111. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00350.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchand-Adam S, Marchal J, Cohen M, et al. Defect of hepatocyte growth factor secretion by fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1156–1161. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1514OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinhilber D, Radmark O, Samuelsson B. Transforming growth factor beta upregulates 5-lipoxygenase activity during myeloid cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5984–5988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shim YM, Zhu Z, Zheng T, et al. Role of 5-lipoxygenase in IL-13-induced pulmonary inflammation and remodeling. J Immunol. 2006;177:1918–1924. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peebles RS, Jr, Dworski R, Collins RD, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibition increases interleukin 5 and interleukin 13 production and airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:676–681. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9911063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endo T, Ogushi F, Kawano T, et al. Comparison of the regulations by Th2-type cytokines of the arachidonic-acid metabolic pathway in human alveolar macrophages and monocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:300–307. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.2.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espinosa K, Bosse Y, Stankova J, et al. CysLT1 receptor upregulation by TGF-beta and IL-13 is associated with bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to LTD4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1032–1040. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balbir-Gurman A, Braun-Moscovici Y, Livshitz V, et al. Antioxidant status after iloprost treatment in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1517–1521. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0613-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allan EH, Martin TJ. Prostaglandin E2 regulates production of plasminogen activator isoenzymes, urokinase receptor, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in primary cultures of rat calvarial osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1995;165:521–529. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Ostrom RS, Insel PA. cAMP-elevating agents and adenylyl cyclase overexpression promote an antifibrotic phenotype in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1089–1099. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00461.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kowal-Bielecka O, Distler O, Kowal K, et al. Elevated levels of leukotriene B4 and leukotriene E4 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with scleroderma lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1639–1646. doi: 10.1002/art.11042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selman M, Barquin N, Sansores R, et al. Increased levels of leukotriene C4 in bronchoalveolar lavage from patients with pigeon breeder’s disease. Arch Invest Med (Mex) 1988;19:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia JG, Griffith DE, Cohen AB, et al. Alveolar macrophages from patients with asbestos exposure release increased levels of leukotriene B4. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:1494–1501. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.6.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson WR, Jr, Chiang GK, Tien YT, et al. Reversal of allergen-induced airway remodeling by CysLT1 receptor blockade. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:718–728. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200501-088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly MM, Chakir J, Vethanayagam D, et al. Montelukast treatment attenuates the increase in myofibroblasts following low-dose allergen challenge. Chest. 2006;130:741–753. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierzchalska M, Szabo Z, Sanak M, et al. Deficient prostaglandin E2 production by bronchial fibroblasts of asthmatic patients, with special reference to aspirin-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1041–1048. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuder RM, Zaiman AL. Prostacyclin analogs as the brakes for pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation: is it sufficient to treat severe pulmonary hypertension? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:171–174. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.2.f230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phan SH, Kunkel SL. Inhibition of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by nordihydroguaiaretic acid. The role of alveolar macrophage activation and mediator production. Am J Pathol. 1986;124:343–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Izumo T, Kondo M, Nagai A. Cysteinyl-leukotriene 1 receptor antagonist attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Life Sci. 2007;80:1882–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauvreau GM, Watson RM, O’Byrne PM. Protective effects of inhaled PGE2 on allergen-induced airway responses and airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:31–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9804030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam CM, et al. Variable prostaglandin E2 resistance in fibroblasts from patients with usual interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:66–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-963OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krowka MJ, Ahmad S, de Andrade JA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of iloprost inhalation in adults with abnormal pulmonary arterial pressure and exercise limitation associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:633a. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kujubu DA, Herschman HR. Dexamethasone inhibits mitogen induction of the TIS10 prostaglandin synthase/cyclooxygenase gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7991–7994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molina-Molina M, Serrano-Mollar A, Bulbena O, et al. Losartan attenuates bleomycin induced lung fibrosis by increasing prostaglandin E2 synthesis. Thorax. 2006;61:604–610. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.051946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips PG, Long L, Wilkins MR, et al. cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitors potentiate effects of prostacyclin analogs in hypoxic pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L103–115. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00095.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]