Abstract

DNA has been used to build a variety of devices, ranging from those that are controlled by DNA structural transitions to those that are controlled by the addition of specific DNA strands. These sequence-dependent devices fulfill the promise of DNA in nanotechnology because a variety of devices in the same physical environment can be controlled individually. Many such devices have been reported, but most of them contain one or two structurally robust end states, in addition to a floppy intermediate or even a floppy end state. We describe a system in which three different structurally robust end states can be obtained, all resulting from the addition of different set strands to a single floppy intermediate. This system is an extension of the PX-JX2 DNA device. The three states are related to each other by three different motions, a twofold rotation, a translation of ≈2.1–2.5 nm, and a twofold screw rotation, which combines these two motions. We demonstrate the transitions by gel electrophoresis, by fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and by atomic force microscopy. The control of this system by DNA strands opens the door to trinary logic and to systems containing N devices that are able to attain 3N structural states.

Keywords: three-state device, DNA devices, multiple transitions, nanomachines, sequence specificity

DNA has been used since 1999 to produce a variety of nanomechanical devices (1). Some of these devices are controlled by structural transitions triggered by small molecules or pH. Although interesting, devices controlled by global changes in the environment lack the programmability associated with sequence-dependent devices, controlled by the addition of individual DNA strands. For example, a device based on the B-Z transition of DNA (2) will permit only two states, the B-state and the Z-state, regardless of how many different species are present, although some nuance in Z-forming proclivity (3) might increase this number somewhat. Sequence-dependent devices offer the ability to address a collection of them individually, so that, say, N two-state devices can lead to 2N structural states. For example, a translation machine containing two different sequence-dependent two-state devices has been reported, leading to four different products (4).

The first sequence-dependent DNA device was a tweezers-like machine reported by Yurke and colleagues (5). The key contribution of that group was the introduction of a “toehold” region on a state-setting strand so that it could be removed, thereby enabling an alteration of the structure. A robust nanomechanical device is one that behaves like a macroscopic device: It has well defined endpoints and does not undergo component-changing isomerizations, such as dissociation or dimerization. The tweezers device lacked this robustness in that it could dimerize during the transition between states; in addition, its open state was not geometrically very well defined. Simmel and Yurke (6) later developed a device with two well structured end-states, in addition to a floppy intermediate.

The PX-JX2 device is a robust two-state rotary nanomechanical DNA device controlled by hybridization topology (7). As a function of two different pairs of set strands, one end swivels relative to the other by a half turn; the intermediate state is poorly structured because it has a lot of single-stranded character. The PX-JX2 device lies at the heart of the translation device described above (4). Recently, a cassette was developed to insert the PX-JX2 device into a two-dimensional DNA array (8), thereby enabling a series of these devices to be associated with each other in a larger context; this system creates situations where the number of devices, N, can grow, and the number of possible states of the system, 2N, can grow accordingly.

Another way to increase the total states of a system is to increase the number of states available to each device. We report the development of a three-state device by adding a translational contraction/expansion motion to the previous PX-JX2 device, thereby creating what we call a PX-JX2-BX device. This alteration would increase significantly the number of states in a multicomponent system, 3N vs. 2N. The three states, PX, JX2, and BX, are illustrated in Fig. 1. The PX and JX2 states are similar to those described in ref. 7. They are both controlled by a pair of set strands, drawn in green for the PX state and in yellow for the JX2 state. The green set strands continue a PX structure (9) that is present in the outer regions of the device frame. The yellow set strands also promote the PX structure in the central part of the device, but they lead to two strand juxtapositions near the upper part of the set strand region. This difference leads to a half-turn difference between the tops of their helical domains (indicated as A and B) and the bottoms (C and D). Both strands are removed by binding their complete complements, including the toeholds, which are octanucleotides drawn extending horizontally from the device. This portion of the device differs from previously reported PX-JX2 devices because the set-strand region is much longer (six half-turns of double-helical DNA, rather than three half-turns) and because there is some PX character to the set strand region of the JX2 state.

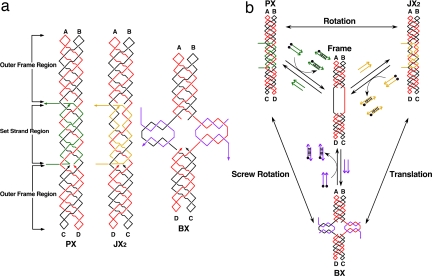

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawings of the three-state device. (a) The PX, JX2, and BX motifs. The Frame consists of two strands, one drawn in red and one in black, where arrowheads indicate the 3′ ends of strands. The outer Frame regions consist of PX-DNA, two double helices wrapped around each other. The green set strands in the PX motif (left) continue this pattern. The toeholds, used to remove the set strands, are drawn as horizontal lines, one on the 5′ end and one on the 3′ end. The set strands in the JX2 motif are drawn in yellow, but the same conventions apply. Note the lack of two crossovers in the set strand region. The set strands in the BX motif are drawn in purple, and the toeholds are vertical. The color-coding of the strands and labels in Fig. 1a indicates that the top ends, A and B, are the same in all of the molecules but that the bottom ends, C and D, are rotated 180° in JX2 and BX molecules. BX is contracted vertically, relative to PX and JX2. (b) Principles of device operation. The three states are shown at the corners of this diagram, and the nature of the transitions (rotation, translation, or screw rotation) is indicated by labels next to the double-headed arrows. All transitions go through the unstructured Frame, shown in the center of the diagram. The addition of set strands (drawn as colored arrows) transforms the Frame to the PX state (green set strands), the JX2 state (yellow set strands), or the BX state (purple set strands). The set strands can be removed from any motif by the addition of the unset or fuel strands, drawn as arrows with black dots (representing 5′ biotin groups), thereby returning the device to the Frame state; the duplex molecules so generated can be removed by the addition of streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

We have added the new state BX, which entails contracting the single-stranded portions of the set strand region of the device frame via the addition of the purple strands (Fig. 1a). The designed structures of the extruded part of the BX state involving the set strands are much like the central portion of a DAO DNA double crossover molecule (10). The set strand region of the device is much longer than in the original PX-JX2 device because we needed to have enough single-stranded DNA to produce a detectable contraction, in addition to the need to have a sufficiently long region to stabilize the set strands in each of two domains on each branch.

Another feature of this system is that there are three different transitional motions between the endpoints. The two-state PX-JX2 device simply rotates a half turn from the PX state to the JX2 state and then rotates through the inverse twofold rotation back to the PX state. The new device also performs this motion between those two endpoints, but in addition, it contracts and expands between the JX2 and the BX state. Furthermore, transitions between the PX state and the BX state correspond to a twofold screw rotation. These motions are shown in Fig. 1b. It should be noted that these motions describe the relationships between the starting and ending states of the transitions. The intermediate, shared by all transitions, is known to be floppy and structurally ill defined (7).

Results

Formation and Operation of the Device.

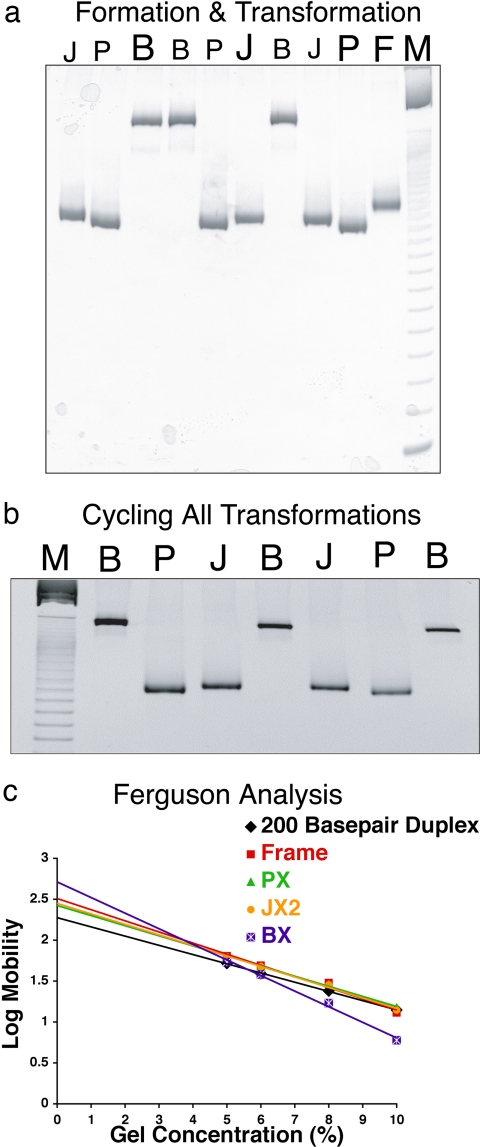

To demonstrate the operation of a robust molecular mechanical device, it is necessary to both show the uniform behavior of the bulk material and visualize the structural transformations of selected molecules. Fig. 2a illustrates the formation and interconversion of the Frame structure PX, JX2, and BX DNA by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. The absence of species other than the PX, BX, or JX2 molecules [for example, the dimers noted by Yurke et al. (5) or potential dissociation products] at the concentrations used attests to the robustness of the device in bulk. Lane F (at right) contains the unstructured intermediate termed “Frame” (1 μM), lane P contains the device (1 μM) assembled with PX set strands, lane J contains the device (1 μM) assembled with JX2 set strands, and lane B contains the device (1 μM) assembled with BX set strands. Gel mobility differs because the PX and JX2 devices are likely to have a more compact time-averaged structure than the BX device; smaller differences between the mobilities of PX and JX2 were noted previously (7). Lanes B and J (left of P) contain the products of removing the PX set strands from the material in lane P and replacing them with set strands corresponding to the BX and JX2 conformations, respectively. Likewise, lanes B and P (left of J) contain the products of removing the JX2 set strands from the material in lane J and replacing them with those corresponding to the BX and PX conformations. Lanes J and P (left of B) contain the products of removing the BX set strands from the material in lane B and replacing them with those corresponding to the JX2 and PX conformation. Note the absence of extraneous products in all lanes containing transformation products, indicating the robustness of the transformations.

Fig. 2.

Gel evidence for the operation of the device. (a) Formation and interconversion of Frame structure and PX, JX2, and BX motifs demonstrated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. This is a 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, run at 22°C and stained with stains-all dye (Sigma E-7762). The lanes are described from the right: lane M, 10-bp ladder marker; lane F, the unstructured intermediate, Frame; lane P, the device assembled with PX set strands; lane J, the device assembled with JX2 set strands; lane B, the device assembled with BX set strands. Lanes J and B (left of P) contain the products of removing the PX set strands from the material in lane P and replacing them with set strands corresponding to BX and JX2, respectively. Lanes B and P (left of J) contain the products of removing the JX2 set strands from the material in lane J and replacing them with those corresponding to BX and PX. Lanes J and P (left of B) contain the products of removing the BX set strands from the material in lane B and replacing them with those corresponding to JX2 and PX. (b) Cycling the device. The gel shows the cycling of the device through six possible transitions starting from any of the three states (here, we have started with BX). Lane M shows the 10-bp ladder marker. Continuing right, lane B is the initial BX conformation, lane P is PX transformed from BX in lane B, lane J is JX2 from PX in lane P, and lane B is BX from the JX2. Proceeding right, lane J is JX2 again from BX in lane B, lane P is PX from JX2 in lane J, and finally lane B is BX from PX in lane P. Thus, BX can be formed after six steps of operation through all possible transitions. (c) Ferguson analysis of the motifs used here. The plots of the PX, JX2, BX, and Frame molecules are compared with a double-helical molecule of similar length.

Fig. 2b contains a nondenaturing gel that shows the cycling of the device through six possible transitions starting from any of the three states (here we have started with BX). Lane M shows a 10-bp ladder marker; proceeding right, lane B is the initial BX conformation, and lane P is PX transformed from the material in the BX state in lane B. It is flanked at right in lane J by JX2 obtained from the material in lane P. To its right in lane B is BX from the JX2. On its right, this material is transformed back to JX2 (lane J), then to PX (lane P), and finally to BX again (lane B at right). Thus, BX can be formed after six steps of operation through all possible transitions between three states. The addition of unset strands, followed by set strands, was repeated five times for the cycle. These data establish the robustness of the device as well as the ability to transform it from any state to any other state.

Ferguson Analysis.

We determined the Ferguson (11) plots of these species by comparing their mobilities as a function of polyacrylamide concentration. The mobility, M, of a molecule as a function of total gel concentration, T, may be described by the well known relationship (12)

where Mo is the free mobility, and KR is the retardation coefficient. Rodbard and Chrambach (13) have shown that KR is an approximately linear function of the exposed surface area (friction constant) of the electrophoresing species. Fig. 2c illustrates the Ferguson plot for all of the robust states of the device, the floppy frame, and a 200-nt-pair duplex, similar in size to the device. The largest slope characterizes the BX device, probably because of its “X” shape. The PX and JX2 molecules are slightly different, as can be seen in the plot, but in both cases they contain large occluded surfaces, which decrease their friction constants relative to the BX structure. Similar behavior is seen with four-arm junctions, which also occlude part of their surfaces (14). These results suggest that the BX structure does not occlude its surface significantly and is thus closer to the 4 × 4 structure (15) than to an eight-helix equivalent of the stacked four-arm junction.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Illustrating the Operation of the Device.

Altered gel mobilities do not guarantee that the construct undergoes the designated structural transformation. We demonstrate this aspect of the device with the system shown in Fig. 3a. We have used half-hexagon trapezoidal markers made of three triangles via edge sharing, as done previously (7, 16). The trapezoids are connected into one-dimensional oligomeric arrays by linkages that include PX-JX2-BX devices. The drawing shows that if the devices are all in the PX state, the trapezoids have a parallel arrangement, and when the devices are all in the JX2 state, the trapezoids form a zigzag structure. If the device is in the BX state, the markers will have the same zigzag orientation as in JX2; however, the distances between individual markers will be smaller, owing to the translational motion, which contracts the device. Although estimated to be small (<3 nm), in one-dimensional arrays the contraction adds up and we see a marked change from end to end. All AFM images shown in Fig. 3 b and c have dimensions of 200 nm × 200 nm.

Fig. 3.

Visualization of the transition of the devices by AFM. (a) A highly simplified representation of the system used. It consists of a one-dimensional array of half-hexagon trapezoids (light blue outer strands, orange inner strands) joined by the device. Each trapezoid consists of three edge-sharing DNA triangles. The color-coding used for the set strands for each oligomer of the device has been retained from Fig. 1, and (in a lighter shade) as background with green set strands in the PX state, yellow set strands in the JX2 state, and purple set strands for the BX state, with constant strands in red and black. The strand topology is both more complex and larger than shown here and is drawn in detail in SI Appendix. There are 40 nucleotides between the first device crossover point and the nearest triangle crossover point, a number that was determined empirically to give the most nearly planar structure. The Frame intermediate is not shown. In the lower molecule, all of the half-hexagons point in the same direction, whereas they point in opposite directions in the upper molecule. Biotinylated fuel strands (with black circles) are shown removing set strands in all parts of the cycle. (b) Control AFM images. The trapezoid oligomer is shown in the PX state in I, in the JX2 state in II, and in the BX state in III. (c) Cycling of the device between two states. c illustrates the operation of the device by displaying representative molecules sampled from solutions as the system is cycled. Upper Left is the initial state, Upper Right and Lower Left are a transformed state, and Lower Right is transformed back to the same state as Upper Left. I shows the system originating in the BX state, converting to the JX2 state, and then back to the BX state. II starts from the BX state, is converted to the PX state, and is then converted back to the BX state. III starts with the JX2 state, forms PX, and returns to JX2.

Fig. 3b contains AFM images of the three states of the oligomers shown in Fig. 3a. These images contain control molecules, not devices, which are constrained to be in the PX, BX, or JX2 motifs. The PX state (Fig. 3bI) contains a series of trapezoids extended parallel to each other, much like the extended fingers of a hand. By contrast, the JX2 state (Fig. 3bII) is characterized by a zigzag arrangement of trapezoids, and the BX state (Fig. 3bIII) is a contracted version of the JX2 state. Fig. 3c illustrates the operation of the device by displaying representative molecules sampled from solutions as the system is cycled. The intermediate state produces a single band on a gel, but it is not well structured when examined by AFM (data not shown). Fig. 3c shows three sets of two-step conversions of the device state. Upper Left in each is the original state, Upper Right and Lower Left are aliquots from the transformed state, and Lower Right shows the return to the original state. In the first set (Fig. 3cI), the system originates in the BX state and is then converted to the JX2 state and back to the BX state. The second set (Fig. 3cII) also begins in the BX state, which is converted to the PX state and back to the BX state. The third set (Fig. 3cIII) begins with the JX2 state, which is converted to PX and then converted back to JX2. The PX device arrays are clearly in a parallel arrangement, and the distance between the units is ≈60 nm; the JX2 device arrays are clearly in the zigzag arrangement, and the half-repeat distance on one side is ≈34 nm; and BX device arrays are in a contracted zigzag orientation with the half-repeat distance on one side at ≈26 nm. Thus, the system operates as designed, both in bulk and in individual cases. The large difference between the PX and JX2 distances, expected to be similar, makes us suspicious of interpreting the BX-JX2 difference (≈8 nm) quantitatively.

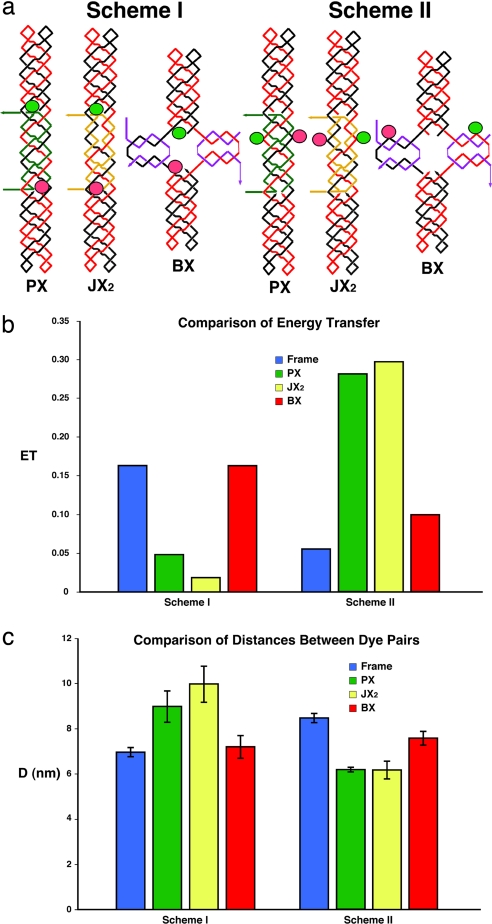

Quantitative Visualization of the Transition via Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Measurements.

Fig. 4a illustrates two different labeling schemes that have been used to yield FRET measurements. The diagrams for the two schemes are similar to those in Fig. 1a, and the conventions there apply here as well. A green ellipse indicates the site where a fluorescein dye has been placed, and a red ellipse indicates the site of a Cy3 unit. Scheme I shows the dye-pairs are far apart in PX and JX2 (theoretical distance: 10.5 nm) but closer in BX (theoretical distance: 4.8 nm). In scheme II, dye-pairs are placed the opposite way where they are closer in PX and JX2 (theoretical distance: 4.8 nm) but far apart in BX (theoretical distance: 11.0 nm). Fig. 4b illustrates the donor energy transfer for device molecules in the three different states and for the two different schemes. In scheme I, the energy transfer trend is PX ≈ JX2 ≪ BX. In scheme II, the trend is PX ≈ JX2 ≫ BX. Fig. 4c converts these measurements into distances between the dye-pairs. In scheme I, the distances follow the expected trend PX (9.0 ± 0.7 nm) ≈ JX2 (10.0 ± 0.8 nm) > BX (7.2 ± 0.5 nm). In scheme II, the trend is PX (6.2 ± 0.1 nm) ≈ JX2 (6.2 ± 0.4 nm) < BX (7.6 ± 0.3 nm). These distance estimates are in agreement with the models shown in Fig. 4a, and the range of the errors does not lead to ambiguity. The similarities between the PX and JX2 distances lead us to accept the BX-JX2 differences of 2.1–2.5 nm as being more reliable than the larger differences seen by AFM.

Fig. 4.

FRET data for the motifs used here. (a) Labeling schemes used for the experiments. Two sets of molecules are shown, corresponding to two different labeling schemes. The molecules are drawn according to the conventions in Fig. 1a, but they now include green ellipses to represent the locations of fluorescein donor dyes and red ellipses to represent the locations of Cy3 acceptor dyes. (b) Donor energy transfer for the frame plus the device molecules in three different states and for two different labeling schemes. The color-coding is indicated. The ordinate shows the extent of donor energy transfer. (c) Distances between the dye-pairs plotted for device molecules in three different states and for two different labeling schemes. Color-coding is the same as in b. The ordinate shows the distance (D) of the dye-pairs. Standard deviations are indicated.

Discussion

Construction of the Device.

We have built and demonstrated a robust DNA nanomechanical device with three well structured endpoints, as well as a weakly structured common intermediate. Gel evidence for the end states of ensembles of the device is clear, so that neither multimerization nor breakdown of the motif is seen after the transition. Data from both FRET and AFM clearly support the operation of the device as engineered. The route to a robust three-state device from its predecessor two-state PX-JX2 device was not straightforward. Extending the control region from three to six half-turns to permit the formation of the BX state was successful, but extending it to seven half-turns was unsuccessful. Seven half-turns was the product of adding a full PX turn to the control region. However, the presence of three major groove half-turns and four minor groove half-turns led to smeared or split bands in the PX and JX2 states, whereas four major groove half-turns and three minor groove half-turns led to split bands in the BX state. Model building (17) confirmed that it is necessary to have an even number of half turns in the control region of the three-state device. Nevertheless, the frame of the six-half-turn molecule was found to be unstable unless we extended its outer portions from three to five half-turns.

Features of the Device.

Robust devices built previously had two well defined endpoints, so a collection of N independent devices were capable of forming 2N independent states, perhaps representative of binary logic or other sets of states. Under similar circumstances, this device is capable of forming 3N states, leading, perhaps, to trinary logic but certainly to greater diversity of physical states. Currently, this device, like most of its predecessors, is a shape-shifter when free in solution. Were this device to be incorporated into a cassette capable of insertion into a two-dimensional DNA array (8), tiles of different sizes, as well as different sticky ends (18), could be directed to form arrays.

The uses of a nanorobotic device can derive either from the number of states in its endpoints or from the number and types of different structural transitions between those endpoints. This device has three different physical transition types between endpoint states under the control of the set strands, regardless of transition mechanism: the twofold rotation between PX and JX2, the translation between JX2 and BX, and the twofold screw rotation between PX and BX. In general, there will be N!/[(N − 2)! 2!] different transition types between endpoints associated with an N-state device; of course, each transition can go in two different directions. It is not hard to imagine extending the device reported here to more than three states and correspondingly more structural transitions. For example, the two ends of the frame could be bent toward one another by an appropriate pair of set strands. Although one can obtain multiple states by combining many different simple, say two-state, devices, combinations of identical devices will not display the variety of transitional movements of which multiple-state devices are capable.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Design.

The sequences were designed by using the program Sequin (19) to apply the principles of sequence symmetry minimization, within the constraints of this system. The crossover points on each strand are predetermined in a PX-6:5 molecule (9) with an asymmetric sequence; crossover isomerization would produce mispairing because major groove unit tangles would become minor groove unit tangles and vice versa (9). The sequences of the molecules used are given in supporting information (SI) Appendix.

Synthesis and Purification of DNA.

All DNA molecules in this study were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 394 automatic DNA synthesizer, removed from the support, and deprotected, using routine phosphoramidite procedures (20). All of the DNA strands were purified by using denaturing gel electrophoresis. Fluorescein-modified strands are the products of incorporating Fluorescein-on phosphoramidite (Clontech). Cy3 labeling was done by filling-in Cyanine 3-dCTP (PerkinElmer) with Klenow Fragment (NEB) DNA polymerase, according to a protocol suggested by the supplier. Strands longer than 120 nt were produced by ligating shorter fragments.

Formation and Transformation of Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes.

Complexes were formed by mixing a stoichiometric quantity of each strand, as estimated by OD260, in a solution containing 40 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM acetic acid, 2 mM EDTA, and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate (TAE/Mg). This mixture was then heated to 90°C for 5 min and cooled to the desired temperature by the following protocol: 15 min at 65°C, 30 min at 45°C, 20 min at 37°C, and 30 min at room temperature. Stoichiometry was determined by titrating pairs of strands designed to hydrogen bond together and visualizing them by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis; absence of monomer bands was taken to indicate the endpoint (21). To achieve transitions between states, unset (fuel) strands were added to the preformed PX, BX, or JX2 molecules at 22°C and kept at 22°C overnight. The mixture was treated with streptavidin beads at 22°C for 30 min to remove the set-strand/unset-strand duplexes. After removing the set strands of PX, BX, or JX2, the set strands of the next target molecules were added to the solution and kept at 22°C for 3 h to establish the targeted device conformation. Set strand removal took 2–3 h at 22°C, except for BX, which took 6 h; all removals can be performed in 30 min at 37°C.

Ligation.

One unit of T4 polynucleotide ligase (Amersham) was added to a buffer supplied by the manufacturer that had been brought to 1 mM in ATP; the reaction was allowed to proceed at 16°C for 7 h. The reaction was stopped by phenol/chloroform extraction. Samples were then ethanol-precipitated.

Nondenaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis.

Gels contained 6–10% acrylamide (19:1, acrylamide/bisacrylamide). DNA was suspended in 10–25 μl of a solution of TAE/Mg buffer; the quantities loaded varied as noted. Gels were prepared and analyzed as described in ref. 10.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Measurements.

Steady-state fluorescence measurements were performed with an AMINCO BOWMAN Series 2 spectrometer at room temperature. The emission spectra were corrected for instrument response, lamp fluctuations, and buffer contributions; energy transfer and distances were calculated according to refs. 2 and 22.

Atomic Force Microscopy.

AFM samples were prepared as described in ref. 7.

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-29554; National Science Foundation Grants DMI-0210844, EIA-0086015, CCF-0432009, CCF-0523290, CTS-0548774, and CTS-0608889; Army Research Office Grant 48681-EL; Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-06ER64281 (subcontract from the Research Foundation of the State University of New York), and a grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Footnotes

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “Nanomaterials in Biology and Medicine: Promises and Perils,” held April 10–11, 2007, at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC. The complete program and audio files of most presentations are available on the NAS web site at www.nasonline.org/nanoprobes.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0707681105/DC1.

References

- 1.Seeman NC. From genes to machines: DNA nanomechanical devices. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao C, Sun W, Shen Z, Seeman NC. A nanomechanical device based on the B-Z transition of DNA. Nature. 1999;397:144–146. doi: 10.1038/16437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du SM, Stollar BD, Seeman NC. A synthetic DNA molecule in three knotted topologies. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1194–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao S, Seeman NC. Translation of DNA signals into polymer assembly instructions. Science. 2004;306:2072–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1104299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurke B, Turberfield AJ, Mills AP, Jr, Simmel FC, Neumann JL. A DNA-fuelled molecular machine made of DNA. Nature. 2000;406:605–608. doi: 10.1038/35020524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmel FC, Yurke B. A DNA-based molecular device switchable between three distinct mechanical states. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;80:883–885. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan H, Zhang X, Shen Z, Seeman NC. A robust DNA mechanical device controlled by hybridization topology. Nature. 2002;415:62–65. doi: 10.1038/415062a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding B, Seeman NC. Operation of a DNA robot arm inserted into a 2D DNA crystalline substrate. Science. 2006;314:1583–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1131372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen Z, Yan H, Wang T, Seeman NC. Paranemic crossover DNA: A generalized Holliday structure with applications in nanotechnology. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1666–1674. doi: 10.1021/ja038381e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu T-J, Seeman NC. DNA double-crossover molecules. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3211–3220. doi: 10.1021/bi00064a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson KA. Starch-gel electrophoresis—Application to the classification of pituitary proteins and polypeptides. Metabolism. 1964;13:985–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(64)80018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodbard D, Chrambach A. Unified theory for gel electrophoresis and gel filtration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;65:970–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.4.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodbard D, Chrambach A. Estimation of molecular radius, free mobility, and valence using polyacylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1971;40:95–134. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Mueller JE, Kemper B, Seeman NC. Assembly and characterization of five-arm and six-arm DNA branched junctions. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5667–5674. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan H, Park SH, Finklestein G, Reif JH., LaBean TH. DNA-templated self-assembly of protein arrays and highly conductive nanowires. Science. 2003;301:1882–1884. doi: 10.1126/science.1089389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong H, Seeman NC. RNA used to control a DNA rotary nanomachine. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2899–2903. doi: 10.1021/nl062183e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeman NC. Physical models for exploring DNA topology. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1988;5:997–1004. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1988.10506445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carbone A, Seeman NC. Circuits and programmable self-assembling DNA structures. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12577–12582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202418299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeman NC. De novo design of sequences for nucleic acid structural engineering. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1990;8:573–581. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1990.10507829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caruthers MH. Gene synthesis machines: DNA chemistry and its uses. Science. 1985;230:281–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3863253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeman NC. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. New York: Wiley; 2002. Unit 12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. Determination of DNA helical handedness by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:597–617. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]