I am pleased to comment on “Visualizing the dynamics of viral replication in living cells via TAT peptide delivery of nuclease-resistant molecular beacons,” by Hsiao-Yun Yeh et al. (1), appearing in this issue of PNAS. I regard it as a very important contribution to animal (including human) virology because it allows observation of early events in virus replication in the host cell.

The work by Yeh et al. (1) has several ramifications. First, it provides evidence of a specific virus infection more rapidly than any presently available method. Although some forms of molecular testing (e.g., real-time RT-PCR) might be more rapid, molecular tests cannot distinguish whether the detected virus was infectious or inactivated at the time of sampling. This means that the method of Yeh et al. could be of exceptional value in environmental monitoring and, perhaps, counterterrorism. Second, it offers a basis for quantification of viral infectivity, which can be used to demonstrate inactivation of virus by various treatments and thus afford a basis for comparing risk-management measures. Third, it should be applicable to the detection of viruses that infect host cells without killing them; this would potentially offer detection of some viruses that never kill host cells or the use of a single cell line to detect a broader range of viruses than would otherwise be possible.

By way of background, note that bacterial viruses typically complete their replicative cycle in less than an hour under ideal conditions; the cycle ends with a cataclysmic burst of the host cell, releasing all of the progeny virus at once. Animal viruses have much longer replicative cycles; progeny virus may be released gradually; and the host cell may or may not lyse as a consequence of the infection (2).

The present study used coxsackievirus B6 (CVB6), a human picornavirus, to infect cells of a line named Buffalo green monkey kidney (BGMK). The cells, suspended in a nutrient medium, settle onto a sterile glass or plastic surface, spread, and multiply to form a 2-dimensional, confluent layer comprising thousands to millions of cells. The plastic or glass on which the cells are grown must be compatible with the cells and have excellent optical properties, so that the cells can be observed microscopically. If fluorescence microscopy is planned, the glass or plastic must be transparent to the UV excitation light, as well as the visible light that is transmitted to the observer's eyes or to a recording camera.

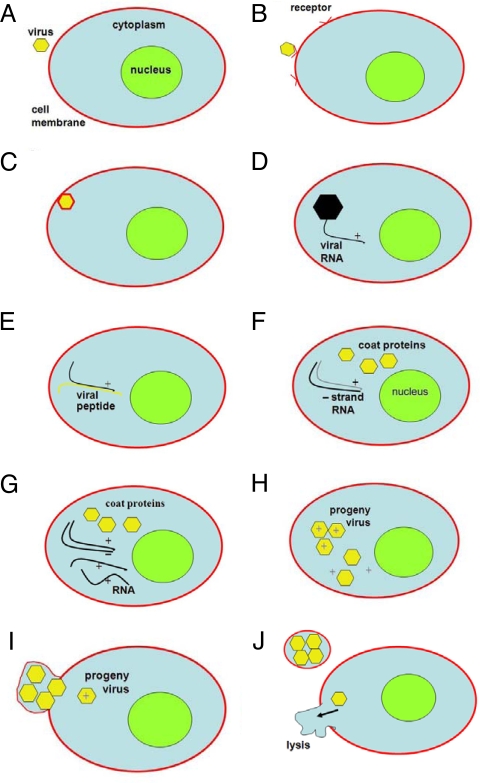

When a picornavirus such as CVB6 is inoculated into the medium on the cells, the individual viral particles (virions) move randomly (Fig. 1A) (2). When a virion contacts a homologous receptor on the plasma membrane of a cell (Fig. 1B)—at least some of the time—the virion is completely engulfed (Fig. 1C), and the protein coat comes off, liberating the viral nucleic acid (Fig. 1D). Picornaviruses have single-stranded, plus-sense RNA, which is directly translated into virus-specific proteins by means of the host cell's synthetic apparatus (Fig. 1E). A portion of the viral RNA at the beginning (5′) end is not translated. The viral protein is a very large peptide that divides itself into smaller, functional units, some of which will become the viral coat, and others that will direct the host cell to produce progeny virus. A key virus-specific protein is RNA-dependent RNA polymerase—this allows the cell to synthesize minus-strand RNA that is complementary to the RNA that was in the virion (Fig. 1F). Plus-sense RNA for the progeny virus is synthesized on this minus-strand template (Fig. 1G). No DNA is involved, and all of the events occur in the cytoplasm of the host cell. Plus-sense RNA and coat protein accumulate in the synthetic site and assemble themselves spontaneously into progeny virus (Fig. 1H). The progeny virus is released from the host cell over time, sometimes in packets surrounded by cell plasma membrane (Fig. 1I). Some viral genomes code for a protein that blocks DNA-dependent RNA synthesis, whereby the host cell eventually dies through inability to synthesize its own specific proteins (Fig. 1J). However, not all viruses block synthesis of host-cell-specific mRNA, so chronic viral infection of a cell is possible. With the virus that does kill the host cell, it is possible to add a gelling agent to the medium, so that cycles of infection produce a localized area of dead cells called a plaque. The virion that initiates a plaque is scored, after-the-fact, as a plaque-forming unit (PFU).

Fig. 1.

Generic, schematic summary of enterovirus replication. (A) Virus moves randomly in space near susceptible cell. (B) Virus contacts homologous receptor on cell's plasma membrane. (C) Virus is engulfed by host cell. (D) Viral RNA emerges from protein coat. (E) Viral peptide is translated from viral RNA. (F) Negative-sense RNA is transcribed from plus-sense viral RNA; coat protein is translated from plus-sense viral RNA. (G) Coat protein and plus-sense viral RNA accumulate at synthetic site. (H) Accumulated components self-assemble into progeny virus. (I) Progeny virus is released in packets, coated with host-cell membrane. (J) Host cell cannot maintain itself, so lysis follows. Adapted from ref. 2.

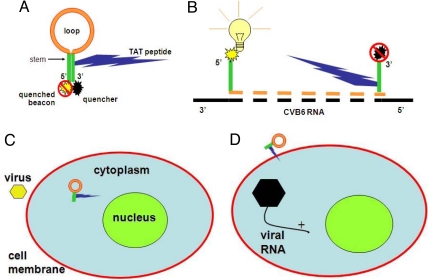

The present investigators have devised a cellular “beacon” that would attach specifically to CVB6 RNA (Fig. 2A). They selected a segment of the nontranslated 5′ end of the RNA, common to the enterovirus genus of the picornavirus family, as their beacon's target. The beacon was synthesized with an alternate backbone that made it insusceptible to RNase (1). Combined with its target sequence in the viral RNA, the beacon gained the ability to fluoresce in response to UV excitation (Fig. 2B). The beacon had an entry peptide (TAT) coupled to it, whereby it penetrated the host cell efficiently. When CVB6 entered the host cell and uncoated, the beacon attached to the target RNA sequence and became fluorescent (Fig. 2C). Fluorescence could be perceived in as little as 15 min, and within 2 h if only a PFU was inoculated. The fluorescence was not seen in uninfected cells and did not occur in the absence of the molecular beacon (MB) or of the TAT-penetrating peptide. Fluorescence could be seen spreading from cell to cell through cycles of infection; and fluorescence was eventually seen outside the cells upon lysis of the host cell. Results should have been similar with any line of host cells supporting CVB6 replication and with any other human enterovirus (>70 serotypes), because the target sequence is shared. The MB might also have been added while the infection was in progress (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 2.

Composition and function of molecular beacon (MB). (A) Loop (orange) is the probe portion of the MB, synthesized with modified bases and “backbone,” so as to be insusceptible to nucleases; stem segments (green) complement each other and hold the quencher (black) and beacon (yellow) together so that the beacon cannot fluoresce in response to UV irradiation; the TAT peptide (dark blue) facilitates entry of the MB into the host cell. (B) When the probe anneals to the homologous segment of the viral RNA (in the 5′ nontranslated region), the quencher and the beacon are separated, allowing the beacon to fluoresce in response to UV excitation. (C) If the MB is in the cell before the virus arrives, fluorescence occurs within 2 h. (D) If the MB enters while the infection is in progress, fluorescence may be seen as soon as 15 min.

The essential elements of the present technique are: (i) design of an appropriate probe sequence for the MB, (ii) synthesis of the MB from constituents that resist nuclease degradation, and (iii) attachment of the TAT peptide to the MB, to facilitate entry into host cells. The authors state that none of these elements is really new—MBs are already used in many ways (3–6), programs for probe sequence design are available on-line (1), nuclease-resistant constituents have been available for several years (1, 7–10), and the TAT peptide from HIV type 1 was described years ago (11, 12). What is significant here is the combination of these elements to achieve a highly desirable end. As stated earlier, many applications can be envisioned. This will probably not solve the problem of viruses that do not infect cell cultures (13). However, it may be possible to use the TAT peptide to introduce viral RNA into otherwise-insusceptible cultured cells to permit one replicative cycle; the occurrence of replication would be demonstrated with an appropriate MB. This technique appears to have brought new light to the study of virus infection at the cell level.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 17522.

References

- 1.Yeh H-Y, Yates MV, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Visualizing the dynamics of viral replication in living cells via TAT peptide delivery of nuclease-resistant molecular beacons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17522–17525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807066105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cliver DO. In: Foodborne Diseases. Cliver DO, editor. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Molecular beacons: Probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyagi S, Alsmadi O. Imaging native beta-actin mRNA in motile fibroblasts. Biophys J. 2004;87:4153–4162. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JJ, Geyer R, Tan W. Using molecular beacons as a sensitive fluorescence assay for enzymatic cleavage of single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E52. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.11.e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh H-Y, Hwang YC, Yates MV, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Detection of hepatitis A virus by using a combined cell culture-molecular beacon assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2239–2243. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00259-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratu DP, Cha BJ, Mhlanga MM, Kramer FR, Tyagi S. Visualizing the distribution and transport of mRNAs in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13308–13313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233244100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotten M, et al. 2′-O-methyl, 2′-O-ethyl oligoribonucleotides and phosphorothioate oligodeoxyribonucleotides as inhibitors of the in vitro U7 snRNP-dependent mRNA processing event. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2629–2635. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.10.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher TL, Terhorst T, Cao X, Wagner RW. Intracellular disposition and metabolism of fluorescently-labeled unmodified and modified oligonucleotides microinjected into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3857–3865. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molenaar C, et al. Linear 2′ O-Methyl RNA probes for the visualization of RNA in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E89–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshayes S, Morris MC, Divita G, Heitz F. Cell-penetrating peptides: Tools for intracellular delivery of therapeutics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1839–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saalik P, et al. Protein cargo delivery properties of cell-penetrating peptides. A comparative study. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1246–1253. doi: 10.1021/bc049938y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duizer E, et al. Laboratory efforts to cultivate noroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:79–87. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]