Abstract

Background

The CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and its ligand, stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1α or CXC chemokine ligand 12) are involved in the trafficking of leukocytes into and out of extravascular tissues. The purpose of this study was to determine whether SDF-1α secreted by host cells plays a role in recruiting inflammatory cells into the periodontia during local inflammation.

Methods

SDF-1α levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of 24 individuals with periodontitis versus healthy individuals in tissue biopsies and in a preclinical rat model of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide–induced experimental bone loss. Neutrophil chemotaxis assays were also used to evaluate whether SDF-1α plays a role in the recruitment of host cells at periodontal lesions.

Results

Subjects with periodontal disease had higher levels of SDF-1α in their GCF compared to healthy subjects. Subjects with periodontal disease who underwent mechanical therapy demonstrated decreased levels of SDF-1α. Immunohistologic staining showed that SDF-1α and CXCR4 levels were elevated in samples obtained from periodontally compromised individuals. Similar results were observed in the rodent model. Neutrophil migration was enhanced in the presence of SDF-1α, mimicking immune cell migration in periodontal lesions.

Conclusions

SDF-1α may be involved in the immune defense pathway activated during periodontal disease. Upon the development of diseased tissues, SDF-1α levels increase and may recruit host defensive cells into sites of inflammation. These studies suggest that SDF-1α may be a useful biomarker for the identification of periodontal disease progression.

Keywords: Chemokine, CXCL12, CXCR4, inflammation, periodontitis, SDF-1α

Periodontal diseases are among the most prevalent infections in humans; they are characterized by the classic hallmarks of the inflammatory response, including erythema and edema.1 Late sequelae of periodontal diseases include the loss of alveolar bone, periodontal ligament attachment, and, ultimately, teeth. Therefore, earlier detection and treatment would lead to improved outcomes for patients.2

Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) is a serum ultrafiltrate of blood originating from the vasculature subjacent to the sulcus. GCF flow rates and the increased concentration of molecules that mediate innate and adaptive immune responses correlate with the severity of periodontal inflammation. As such, numerous GCF constituents have been characterized to identify biomarkers that may be used to monitor the initiation and progression of gingival inflammation and the immune response.

Chemokines are a group of small molecular weight proteins characterized by their ability to induce directional movement of a variety of cell types. Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1α and β or CXC chemokine ligand 12 [CXCL12]) is a potent chemoattractant that belongs to the C-X-C chemokine family, which was originally isolated from a murine bone marrow stromal cell line.3 At least two SDF-1 species have been described that are derived by alternative splicing of the SDF-1/CXCL12 gene and share similar biologic activities. SDF-1α is widely expressed in many tissues during development, including the epithelium surrounding the developing tooth bud.4 SDF-1α is a powerful chemoattractant for hematopoietic cells, including neutrophils; it was demonstrated to facilitate their transmigration across endothelial cell barriers.5 However, vascular endothelial cells in other tissues, such as those lining pulmonary channels, may not secrete SDF-1α.6 This suggests that SDF-1α is selectively expressed by endothelial cells in certain tissues, perhaps in response to specific signals or tissue damage. This may provide a mechanism to localize hematopoietic cells to specific tissue compartments.7-9

Based on the involvement of SDF-1α in hemopoietic cell homing, we hypothesized that the epithelial lining of the gingival sulcus or endothelial cells may secrete the chemokine to recruit mononuclear cells to inflammatory sites. In in vitro studies, we noted that SDF-1α recruited neutrophils, and in preclinical animal models, SDF-1α was expressed in the gingival and sulcular epithelium. GCF samples were collected from clinically healthy subjects and from subjects with chronic periodontal disease. Based on the protein levels, GCF from patients with periodontal disease have significantly higher levels of SDF-1α than subjects without periodontal disease. There was also a decrease in SDF-1α levels collected from sites after successful treatment with local mechanical therapy measures (scaling and root planing). These data suggest that SDF-1α may represent a chemoattractant for host defense cells and may serve as a biomarker in GCF for periodontal diseases.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry for SDF-1α and CXCR4

Archival gingival tissue specimens (N = 12) were obtained from the Division of Oral Pathology, Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, University of Michigan, under a protocol approved by the University of Michigan's Institutional Review Board (IRB). Specimens were obtained from individuals with periodontal disease or from controls with non-inflamed gingiva and no periodontal attachment loss. The samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and 2- to 3-μm slides were prepared. The slides were deparaffinized and dehydrated with xylene, ethanol (100%, 95%, and 70%), and distilled water. The samples were treated with anti-human SDF-1α (immunoglobulin G [IgG]1; clone 79018.111‡‡) for 1 hour at room temperature or an anti-human CXCR4 antibody diluted 1:100 (10 mg/ml), IgG2a (clone 44708.111),§§ or controls (IgG1 or IG2a‖‖) and with a cell and tissue staining kit for mouse primary IgG antibodies¶¶ and 1:20 antibody concentration.

Neutrophil Isolation

Normal peripheral blood isolates## containing a mixture of monocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, plasma, and red blood cells were derived from healthy volunteers who were reported to be non-smoking and who had not taken any prescribed medications prior to donation. Neutrophils were recovered from the whole blood anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution (3% citric acid and 6% sodium citrate*** using 4% dextrose†††) and inverted. Half volumes of dextran (6%) and 0.9% NaCl were added, and the mixture was placed at room temperature for 1 hour to separate. The supernatant was centrifuged at 1,150 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 12 minutes at 4°C and then resuspended in ice-cold double-distilled H2O and 0.6 M KCl. It was centrifuged at 1,300 rpm for 6 minutes at 4°C and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), overlaid on ficol-hypaque,‡‡‡ and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C.

SDF-1α Chemotaxis Assay

Recovered neutrophils in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) were loaded in the top chamber (5 × 105 cells/well) of a plate with 5.0-μm pores.§§§ Recombinant human SDF-1α (200 ng/ml)‖‖‖ was added to 650 μl RPMI 1640 with 0.5% BSA in the lower chamber. Cells were incubated for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells that migrated completely to the bottom chamber were counted manually using a hemocytometer.

Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Periodontal Bone Loss Model

The protocol for the induction of alveolar bone loss was adapted from a method previously reported using Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS-mediated bone loss.10,11 The procedures used for LPS isolation from P. gingivalis W83 were described by Darveau and Hancock.12 Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing ∼250 g each [N = 12]) had experimental periodontitis induced by the intragingival delivery of P. gingivalis W83 endotoxin (10 μl of a 1.0-mg/ml preparation). Injection sites included the gingival interproximal regions between the maxillary first, second, and third molars and the mesial aspect of the maxillary first molar. The administrations were repeated three times per week over an 8-week period using custom-designed 0.375-inch, 33-gauge, 30° bevel needles attached to a 50-μl syringe.¶¶¶ Control animals were treated with PBS vehicle via the same delivery routine. At sacrifice, block biopsies of the maxillae were harvested and immediately fixed in 10% formalin at 4°C, decalcified in 10% EDTA (pH 7.4) for 10 days, and embedded in paraffin.

Study Populations

Power calculations were performed to estimate the required sample size.### A minimum of 11 subjects per group was required for a 95% chance of detecting a statistically significant difference between the healthy and diseased groups at an alpha set at 0.05 and the power of the study set at 80%. Twenty-four subjects from the Comprehensive Care Clinics at University of Michigan School of Dentistry, who consented to participate in a study approved by the University of Michigan IRB Health, were evaluated between June 2003 and December 2005. Inclusion criteria for diseased subjects included the presence of ≥15 teeth and a diagnosis of generalized chronic periodontitis. Subject inclusion criteria for periodontitis were the presence of at least four periodontal sites with probing depth (PD) ≥4 mm, evidence of clinical attachment loss (CAL), and bleeding on probing (BOP). Inclusion criteria for healthy individuals included PD <4 mm, no evidence of attachment loss, and <10% of sites with BOP. Exclusion criteria for healthy subjects included diabetes, immunocompromised subjects, presence of orthodontic devices, periodontal treatment 12 months prior to the initiation of the study, or individuals who had taken antibiotics within 6 months prior to the clinical examination. The medical and dental histories of the subjects were obtained by a standardized health questionnaire. PD and CAL were measured at six sites per tooth (mesio-buccal, buccal, disto-buccal, mesio-lingual, lingual, and disto-lingual) using a periodontal probe. When possible, four of the deepest sites in each quadrant were selected for sampling in each subject. The selected sites corresponded to the deepest PDs associated with ≥1 mm of CAL and the presence of BOP. No specific instructions pertaining to oral hygiene or diet prior to sample collection were provided to the subject.

To determine whether SDF-1α is involved in targeting inflammatory cells to human periodontal lesions, the presence of SDF-1α in the GCF of healthy and diseased individuals was explored. The clinical parameters of the participants are presented in Table 1. Ten healthy subjects and 14 subjects who were diagnosed as “diseased” met the inclusion criteria for the study. The group consisted of seven males and 17 females ranging between 18 and 89 years of age (mean, 46.57 ± 19.60 years) (Table 1). Twenty-four sites were sampled from healthy subjects, whereas 45 sites were sampled from those with disease. The mean PD at healthy sites was 2.2 ± 0.6 mm compared to 5.2 ± 1.4 mm at diseased sites with 1.4 ± 0.6 mm loss of clinical attachment. Ten percent of the healthy sites sampled displayed BOP compared to 93% of the diseased sites (Table 1). In some cases, diseased subjects required initial periodontal therapy consisting of oral hygiene instruction and scaling and root planing. These therapies ranged from two to four sessions of 60 to 90 minutes each under local anesthesia in the undergraduate clinics at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Table 1. Characteristics of Subjects According to Age, Gender, Smoking History, and Periodontal Status.

| Healthy | Periodontal Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 10 | 14 |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity (n) | ||

| White | 6 | 8 |

| Black | 2 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 3 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 44.7 ± 16.6 | 46.1 ± 24.2 |

| Range | 22 to 65 | 18 to 89 |

|

| ||

| Males (n) | 30.0% (3) | 28.6% (4) |

|

| ||

| Sites examined (n) | 24 | 45 |

|

| ||

| Attachment loss (mm) | ||

| Mean | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 0.9* |

| Range | 0.0 to 0.0 | 1.0 to 4.0 |

|

| ||

| PD (mm) | ||

| Mean | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 1.4* |

| Range | 1.0 to 3.0 | 4.0 to 8.0 |

|

| ||

| BOP (n subjects) | 10% (1) | 93% (13) |

|

| ||

| Smoking history (mean [pack-years]) | ||

| Current | 3 (23) | 0 |

| Past | 0 | 3 (25) |

| None | 7 | 11 |

P <0.05.

SDF-1α Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

SDF-1α levels in GCF were determined from samples collected from gingival sulci or diseased periodontal pockets from the healthy and diseased patients. The samples from healthy subjects were collected from the mesio-buccal surface of the first molars (if present) or the most posterior tooth in the quadrant (if the first molar was absent). Diseased sites were selected as the most severe sites in each quadrant. Each sample was collected from the site after drying and removing supragingival plaque. A gingival fluid collection strip**** was placed in the selected sulcus or periodontal pocket for 30 seconds for GCF collection. Individual samples were placed in 1 ml PBS containing protease inhibitors (protease inhibitor cocktail; 4-[2-aminoethyl] benzesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, aprotinin, bestatin, EDTA, E-64, leupeptin, and pepstatin A††††) and stored at −80°C until assayed. Each sample was analyzed by double antibody sandwich ELISA using recombinant human SDF-1ᇇ‡‡ as a standard. To normalize the resulting SDF-1α levels in the GCF, total protein was determined against a BSA standard.§§§§

Statistical Analysis

Each investigation was repeated at least three times. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used to detect any treatment differences. When significant, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for pairwise differences, using Tukey's multiple comparison adjustment. A 5% significance level was set for all tests.

Results

SDF-1α Is Expressed in Human Tissues Derived From Inflamed Gingiva

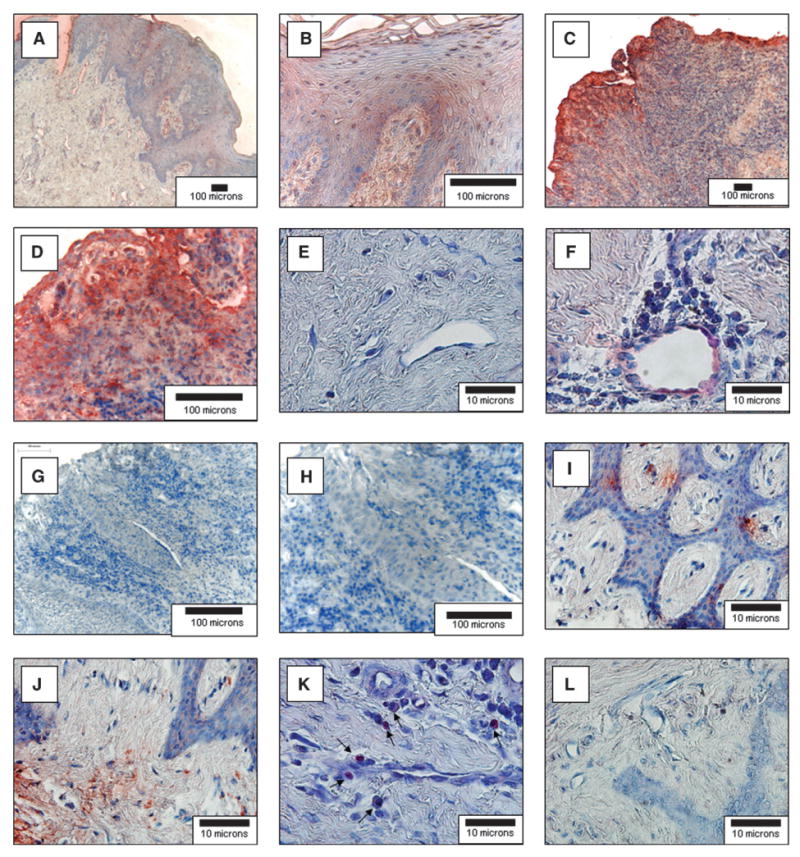

Chronic periodontitis or non-inflamed gingival tissue specimens exhibited staining for SDF-1α by the sulcular and gingival epithelial cells (Figs. 1A through 1D). The SDF-1α staining was significantly more intense in the periodontitis tissues, throughout the thickness of the epithelium (Figs.1C and 1D). The underlying connective tissue also showed evidence of SDF-1α expression in the periodontitis tissues. Vascular endothelial cells were positive in all of the periodontitis tissues (Figs. 1E and 1F). Infiltrating leukocytes were more prominent in areas of localized SDF-1α expression in all of the periodontitis sections and expressed abundant CXCR4 (Figs. 1I through 1K). The few leukocytes seen in the non-inflamed tissues did not stain for SDF-1α (not shown). None of the specimens incubated with non-immune IgG (a control for specificity) demonstrated staining (Figs. 1G and 1H).

Figure 1.

SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression in normal and periodontal diseased human gingiva. Human gingival specimens were stained for the expression of SDF-1α immunohistochemistry (red) and counterstained by hematoxylin (blue). Samples were derived from normal non-inflamed gingival tissues removed for crown-lengthening procedures (A, B, and E) or were obtained from subjects diagnosed with moderate chronic periodontal disease (C, D, and F). G and H) Antibody (IgG1) specificity for the SDF-1 antibodies used by staining moderate chronic periodontal disease tissues. I through L) The samples were derived from subjects diagnosed with moderate chronic periodontal disease and stained for CXCR4 (I, J, K) or an IgG2 control for specificity (L). The sections demonstrate significant cellular infiltrates into the diseased connective tissues and staining for SDF-1α in the epithelia (C and D) and endothelial cells (F). CXCR4 staining in the connective tissues (I and J) and CXCR4 associated with an inflammatory infiltrate (K; arrows). (Original magnification: A, C, and G, × 10; B, D, and H, × 40; E and F and I through L, × 100.)

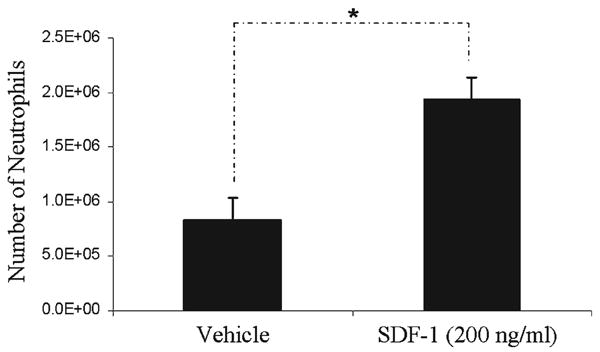

Human Neutrophils Respond to SDF-1α Through Chemotaxis

Next, we investigated whether human neutrophils respond chemotactically to SDF-1α. In vitro chemotaxis assays were performed using peripheral blood obtained from clinically healthy volunteers. As anticipated, 65% ± 3.2% of the assayed neutrophils migrated toward SDF-1α compared to 28% ± 1.4% of the cells in the negative control (PBS) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

SDF-1α acts as a neutrophil chemoattractant Peripheral blood neutrophils (5 × 105) were placed in a plate with a pore size of 5.0 μm with or without the presence of SDF-1α. Neutrophils demonstrated higher migration toward SDF-1α compared to a negative control (PBS). *Significance at P <0.05. E = exponent.

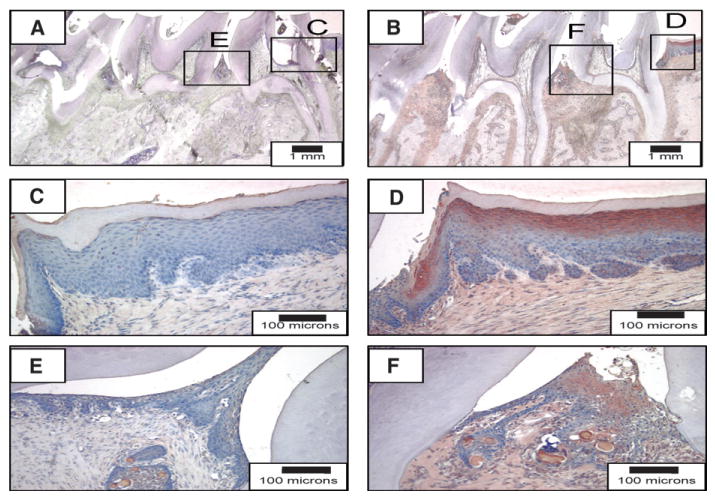

SDF-1α Is Expressed in an Experimental Periodontitis Animal Model

An animal model of experimental periodontitis was used for the induction of alveolar bone loss using P. gingivalis LPS. Animals were sacrificed 8 weeks following disease induction. The experimental protocol of LPS delivery led to localized tissue inflammation and corresponding (∼50% to 80%) alveolar bone destruction (Fig. 3B). In the vehicle-treated animals, minimal to no bone loss and inflammation was noted (Fig. 3A). Weak SDF-1α staining was present throughout the soft tissues of the LPS-injected animals, which was not present in the vehicle-treated animals (not presented), whereas intense staining was observed in the interproximal and retromolar regions. High-powered microscopic examination of the retromolar areas (Figs. 3C and 3D) and interproximal areas (Figs. 3E and 3F) revealed significant SDF-1α staining associated with the P. gingivalis LPS administration.

Figure 3.

SDF-1α expression in P. gingivalis LPS–induced periodontal bone loss. Rats were injected with vehicle (A, C, and E) or P. gingivalis LPS (B, D, and F) for 8 weeks to induce disease. Interproximal (E and F) and retromolar (C and D) regions of the experimental groups. (Horseradish peroxidase 3-amino-9-carbazole stain; original magnification: A and B, ×2; C through F, ×20.)

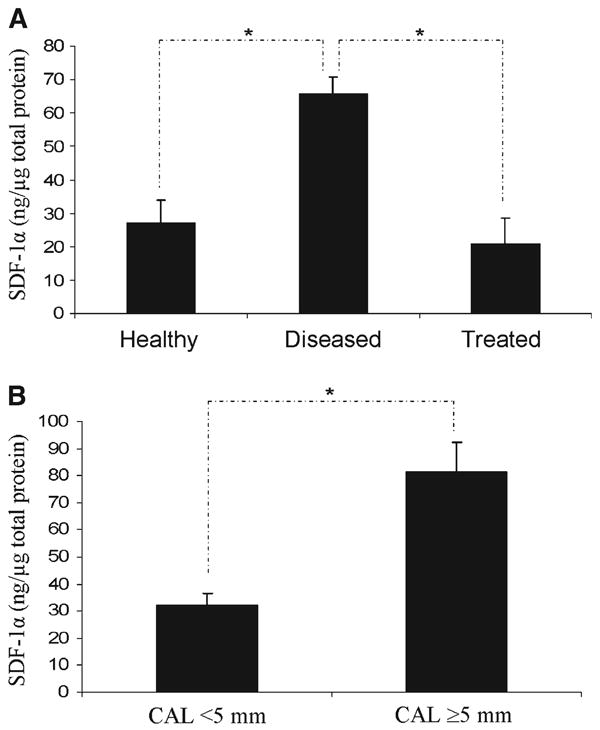

SDF-1α Levels in Human GCF

Preliminary investigations were performed to ensure that the GCF sampling methods were compatible with detecting SDF-1α. SDF-1α was detected by an ELISA assay using known concentrations of recombinant human SDF-1α absorbed onto and eluted from the gingival fluid collection strips (data not shown). Following these studies, the levels of SDF-1α in the GCF of healthy subjects and those with periodontal disease were evaluated and normalized against total protein in the sample. The average level of SDF-1α detected in samples from healthy sites was 27.2 ± 6.8 ng/μg total protein (Fig. 4). Because degradation of SDF-1α plays a significant role in regulating the bioavailability of the chemokine, a second sample, harvested in an identical manner, was collected from these sites. The average concentration of SDF-1α identified in the second sample was 13.9% greater (29.3 ± 10.4 ng/μg); however there was not a significant difference between the two samples (data not presented).

Figure 4.

SDF-1α levels in human GCF in healthy or diseased patients. A) SDF-1α levels in diseased subjects were significantly higher compared to healthy subjects. Subjects who received manual mechanical therapy (scaling and root planing) demonstrated SDF-1α levels comparable to healthy individuals ∼6 weeks after treatment. SDF-1α levels in the GCF of human subjects were stratified by PD. B) Sites with CAL ≥5 mm demonstrated 56% more SDF-1α (76.4 ± 49.3 ng/μg) than sites with PDs <5 mm (32.77 ±21.1 ng/μg). *Significance at P <0.05.

GCF levels of SDF-1α identified in samples collected from diseased sites were significantly higher (65.3 ± 4.91 ng/μg total protein) than the levels detected in healthy sites (27.22 ± 6.39 ng/μg) (Fig. 4A). A select group of subjects initially classified as having attachment loss underwent periodontal therapy consisting of oral hygiene instruction and scaling and root planing. Samples collected from these patients 4 to 8 weeks (mean, 6 ± 1.5 weeks) following initial therapy demonstrated a 68% mean decrease in SDF-1α levels from 65.7 ± 5.0 ng/μg total protein to 21.0 ± 7.6 ng/μg total protein. As before, a second sample of GCF from this set of individuals revealed that the initial sample contained less SDF-1α, possibly representing protein degradation. Stratifying the samples by PD, those derived from sites with PDs ≤5 mm had significantly lower SDF-1α levels (32.77 ± 21.1 ng/mg) compared to sites with PDs >5 mm (76.4 ± 49.3 ng/mg) (Fig. 4B). The levels of SDF-1α detected from healthy and diseased sites in males tended to be higher than in females; however, these differences were not significant (data not shown). There were no differences noted between the SDF-1α levels in diseased smoking subjects relative to diseased nonsmoking subjects (data not shown).

Discussion

These studies demonstrated that SDF-1α levels change in response to periodontal inflammation. In sites with no or minimal CAL (≤5 mm) demonstrated SDF-1α levels at 27.2 ± 6.8 ng/μg total protein. GCF samples derived from sites with the greatest CAL (e.g., subjects with periodontitis) demonstrated significantly higher levels of SDF-1α (65.7 ± 4.91 ng/mg total protein). This level of SDF-1α represents roughly one-third to one-half of that required to induce neutrophil chemotaxis. This suggests that individual periodontal sites, the epithelial lining of the periodontal sulcus or pocket, may release higher concentrations of SDF-1α to attract more neutrophils to amplify the immune response corresponding to the aggressiveness of the disease. Because it is unlikely that SDF-1α serum levels change in response to local infections, our findings agree with the histologic observations that SDF-1α provides a biologic explanation for cellular trafficking into the local periodontal infection sites.

Classic immunopathological studies on the progressive “natural history” of periodontal diseases reported that the earliest detectable lesion (or “initial lesion”) that can be observed after oral hygiene treatment usually occurs within 2 to 4 days and begins as a classic vasculitis.13 Initially, neutrophils or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) migrate through the coronal aspects of the junctional epithelium and may play a destructive role in the loss of contact between the tooth and the junctional epithelium, thereby initiating the formation of pocket epithelium.14 Once located against the sulcular epithelium and possibly entering into the gingival crevice, neutrophils are known to degranulate while in the process of ingesting plaque bacteria. Complement and other acute-phase proteins derived from the vasculature are believed to play an important role in the initiation of host defenses against local periodontal infections.15 These and other proteins may participate in periodontal pathogenesis by recruiting acute and chronic inflammatory cells attempting to neutralize pathogens and their toxins.

Macrophages and lymphocytes are key cells involved in the host response and the early destruction of periodontal tissues. It is well known that neutrophils are key cells involved in the host response and early destruction of periodontal tissues.16-18 In addition, previous studies19-23 showed leukocytes to be responsive to SDF-1α. Therefore, based on the observation that the epithelium expresses SDF-1α, a chemoattractant for neutrophils, which are abundant in the gingival crevicular area during gingival inflammation, we reasoned that SDF-1α may regulate the transepithelial migration of neutrophils into the gingival lesions.

The mechanism that regulates the expression of SDF-1α in the gingiva is poorly understood. Under most conditions, SDF-1α is expressed under basal conditions that may be modified by inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines. The cytokines interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 have been the most widely examined when the response seems to be largely dependent on the cell type studied. For example, using primary dermal and gingival fibroblasts, Fedyk et al.24 observed that monocyte-derived IL-1 and TNF-α decreased SDF-1α secretion. Likewise, TNF-α, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and TGF-β1 enhanced SDF-1 expression by human gingival fibroblasts, whereas heat killed P. gingivalis, and P. gingivalis LPS reduced SDF-1α production.25 Other inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-6 and -8, were not able to regulate the production of SDF-1α by human dermal fibroblasts.24 For thyroid fibroblasts and thymocytes, both of which express basal levels of SDF-1α mRNA, IL-1 and TNF do not seem to alter SDF-1α secretion significantly.26 Likewise, SDF-1α production by bone marrow–derived endothelium is enhanced or decreased by IL-1 or TNF, respectively.27 VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were reported to increase SDF-1α expression in endothelial cells28 and in several prostate cancer cell lines.16 Conversely, SDF-1α did not induce the secretion of VEGF in all cells examined.16-18 Similarly, VEGF stimulates SDF-1α production, but SDF-1α may not alter VEGF production in prostate cancer cell lines.16 These findings suggest that SDF-1α may participate in VEGF- and bFGF-regulated autocrine signaling systems that are essential regulators of endothelial cell morphogenesis and angiogenesis. It was shown recently that VEGF expression is increased in periodontal wounds following the reparative process.29 Furthermore, Wright et al.30 demonstrated that SDF-1α expression is a target of TGF-β1 regulation. Under inflammatory conditions, downregulation of SDF-1α production at local sites of inflammation during the repair process may promote wound healing by resolving the inflammatory phase and limiting the infiltration of monocytes. Thus, the maintenance of normal tissue architecture seems to be a pivotal role for SDF-1α, and its loss or reduced expression may be altered in inflammation.30

It is unknown why SDF-1α is produced at epithelial surfaces. However, SDF-1α may play a key role in the activation of the efferent immune system by regulating dendritic cell migration in addition to its role in regulating PMNs. Dendritic cells function as sentinels of the immune system by trafficking from the vasculature to the tissues where, while immature, they capture antigens.31 Then, following inflammatory stimuli, they leave the tissues and move to the draining lymphoid organs where, converted into mature dendritic cell, they prime naive T cells. A study31 demonstrated that immature dendritic cells respond to many inducible chemokines, including SDF-1α, and, therefore, are likely to respond to agents that alter SDF-1α levels. Epithelial cells lining the gastrointestinal mucosal surface, like those of the gingival crevice, create a physical barrier between the external luminal environment and are a key component of the mucosal innate immune system. Mucosal integrity is partially preserved by epithelial cell migration and turnover. Smith et al.32 demonstrated the expression of several chemokine receptors, notably CXCR4, CCR5, CCR6, and CX3CR1, by the cells of the human intestinal epithelium, suggesting that cells of the mucosal barrier are likely targets for chemokine signals. Akimoto et al.33 demonstrated that healing of human gastric ulcers express high levels of VEGF receptors early in ulcer development, and SDF-1α participates in the initial stage of angiogenesis. SDF-1α receptors are primarily expressed during the later stages of wound healing, which suggests that SDF-1α may also be involved in vascular maturation and gastric mucosal regeneration during late angiogenesis.33 Basal levels of SDF-1α production and secretion into the GCF may maintain the presence of immune surveillance mechanisms in the gingival connective tissues.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the expression of SDF-1α in periodontal lesions and corresponding release in the oral fluids (GCF) associated with diseased periodontal sites. Furthermore, the induction of SDF-1α was noted following the development of periodontitis in a P. gingivalis LPS–mediated model of periodontal disease progression. Thus, these data suggest that SDF-1α may have a role in the development of periodontal disease. Future studies may aid in the determination of the role SDF-1α serves as a biomarker of the risk for periodontal disease progression.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the assistance of the University of Michigan Student Research Opportunity; Dr. Rodrigo Neiva, Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, University of Michigan School of Dentistry, for his technical support; and support from the Delta Dental Foundation of Okemos, Michigan. Dr. Giannobile is supported by The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE 16619), Bethesda, Maryland. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Footnotes

R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN.

R&D Systems.

Sigma, St. Louis, MO.

Cell and Tissue Staining Kit for Mouse Primary IgG Antibodies, R&D Systems.

Normal Peripheral Blood Leukopaks, Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ.

Sigma.

Mallinckrodt Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ.

Histopaque-1077, Sigma.

Costar Transwell, Corning, Lowell, MA.

R&D Systems.

Hamilton, Reno, NV.

DSS Research, Fort Worth, TX.

Periopaper, Oraflow, Plainview, NY.

Sigma.

R&D Systems.

RC DC Protein Assay Kit, BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA.

References

- 1.Kornman KS, Page RC, Tonetti MS. The host response to the microbial challenge in periodontitis: Assembling the players. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:33–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinney JS, Ramseier CA, Giannobile WV. Oral fluid-based biomarkers of alveolar bone loss in periodontitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098:230–251. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagasawa T, Nakajima T, Tachibana K, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a murine pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor/stromal cell-derived factor 1 receptor, a murine homolog of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 entry coreceptor fusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14726–14729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath KE, Koniski AD, Maltby KM, McGann JK, Palis J. Embryonic expression and function of the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor, CXCR4. Dev Biol. 1999;213:442–456. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai K, Kobayashi M, Wang J, et al. Selective transendothelial migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells: A role in homing of progenitor cells. Blood. 1999;93:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai K, Kobayashi M, Wang J, et al. Selective secretion of chemoattractants for haemopoietic progenitor cells by bone marrow endothelial cells: A possible role in homing of haemopoietic progenitor cells to bone marrow. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:905–911. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:108–115. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rottman JB. Key role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation, immunity, neoplasia, and infectious disease. Vet Pathol. 1999;36:357–367. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-5-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park CH, Abramson ZR, Taba M, Jr, et al. Three-dimensional micro-computed tomographic imaging of alveolar bone in experimental bone loss or repair. J Periodontol. 2007;78:273–281. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Neutrophil-mediated host response to Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2002;4:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darveau RP, Hancock RE. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:831–838. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.831-838.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page RC, Schroeder HE. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab Invest. 1976;34:235–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiainen L, Asikainen S, Saxen L. Puberty-associated gingivitis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:87–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zadeh HH, Nichols FC, Miyasaki KT. The role of the cell-mediated immune response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:239–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai J, Kitagawa Y, Zhang J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor contributes to the prostate cancer-induced osteoblast differentiation mediated by bone morphogenetic protein. Cancer Res. 2004;64:994–999. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bautz F, Rafii S, Kanz L, Mohle R. Expression and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor-A by cytokine-stimulated hematopoietic progenitor cells. Possible role in the hematopoietic microenvironment. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:700–706. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kijowski J, Baj-Krzyworzeka M, Majka M, et al. The SDF-1-CXCR4 axis stimulates VEGF secretion and activates integrins but does not affect proliferation and survival in lymphohematopoietic cells. Stem Cells. 2001;19:453–466. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-5-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HK, Kim JE, Chung J, Han KS, Cho HI. Surface expression of neutrophil CXCR4 is down-modulated by bacterial endotoxin. Int J Hematol. 2007;85:390–396. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.A30613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenoir M, Djerdjouri B, Perianin A. Stroma cell-derived factor 1α mediates desensitization of human neutrophil respiratory burst in synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritic patients. J Immunol. 2004;172:7136–7143. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link DC. Neutrophil homeostasis: A new role for stromal cell-derived factor-1. Immunol Res. 2005;32:169–178. doi: 10.1385/IR:32:1-3:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelus LM, Bian H, Fukuda S, et al. The CXCR4 agonist peptide, CTCE-0021, rapidly mobilizes polymorpho-nuclear neutrophils and hematopoietic progenitor cells into peripheral blood and synergizes with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedyk ER, Jones D, Critchley HO, et al. Expression of stromal-derived factor-1 is decreased by IL-1 and TNF and in dermal wound healing. J Immunol. 2001;166:5749–5754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosokawa Y, Hosokawa I, Ozaki K, et al. CXCL12 and CXCR4 expression by human gingival fibroblasts in periodontal disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:467–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aust G, Steinert M, Kiessling S, Kamprad M, Simchen C. Reduced expression of stromal-derived factor 1 in autonomous thyroid adenomas and its regulation in thyroid-derived cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3368–3376. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yun HJ, Jo DY. Production of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and expression of CXCR4 in human bone marrow endothelial cells. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:679–685. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.5.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvucci O, Yao L, Villalba S, et al. Regulation of endothelial cell branching morphogenesis by endogenous chemokine stromal-derived factor-1. Blood. 2002;99:2703–2711. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooke JW, Sarment DP, Whitesman LA, et al. Effect of rhPDGF-BB delivery on mediators of periodontal wound repair. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1441–1450. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright N, de Lera TL, Garcia-Moruja C, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 down-regulates expression of chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1: Functional consequences in cell migration and adhesion. Blood. 2003;102:1978–1984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K, et al. Dendritic cell biology and regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by chemokines. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2000;22:345–369. doi: 10.1007/s002810000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JM, Johanesen PA, Wendt MK, Binion DG, Dwinell MB. CXCL12 activation of CXCR4 regulates mucosal host defense through stimulation of epithelial cell migration and promotion of intestinal barrier integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G316–G326. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00208.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akimoto M, Hashimoto H, Maeda A, Shigemoto M, Yamashita K. Roles of angiogenic factors and endothelin-1 in gastric ulcer healing. Clin Sci. 2002;103(Suppl 48):450S–454S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S450S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]