Abstract

The aim of this research was to explore the experiences of a group of first-time mothers who had given birth at home or in hospital in Australia. Data were generated from in-depth interviews with 19 women and analyzed using a grounded theory approach. One of the categories to emerge from the analysis, “Preparing for Birth,” is discussed in this article. Preparing for Birth consisted of two subcategories, “Finding a Childbirth Setting” and “Setting Up Birth Expectations,” which were mediated by beliefs, convenience, finances, reputation, imagination, education and knowledge, birth stories, and previous life experiences. Overall, the women who had planned home births felt more prepared for birth and were better supported by their midwives compared with women who had planned hospital births.

Keywords: mothers, first birth, home birth, hospital birth, childbirth education

In Australia, three main settings are available in which to give birth: hospital, home, and birth center. In 2005, 97.5% of women gave birth in hospital, 0.2% at home, and 1.9% in birth centers (Laws, Abeywardana, Walker, & Sullivan, 2007). The relationship between the setting of childbirth and its process and outcome remains controversial (Campbell & Macfarlane, 1994; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007; Tracy et al., 2007). Although attention is most often focused on quantitative research that examines mortality and morbidity associated with the place of birth (Bastian, Keirse, & Lancaster, 1998; Johnson & Daviss, 2005; Tracy et al., 2007; Tyson, 1991), how parity affects the experience of birth in a range of settings and how women prepare for birth in these different settings seem under-researched.

Most of the literature pertaining to preparation for birth focuses more on actual childbirth education and less on the other aspects that influence a woman's perception and experience of birth (Cliff & Deery, 1997; Fabian, Rådestad, & Waldenström, 2004; Lumley & Brown, 1993; Nichols, 1995; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2006). Antenatal childbirth education is informal in many parts of the world, with knowledge of the birth experience and care of children passed from mothers to daughters or from traditional birth attendants (Gagnon & Sandall, 2000). This approach has not been completely lost in the developed world, although evidence suggests that financial, social, environmental, and political challenges are now different for families (Gilding, 2001; Wilson, Meagher, Gibson, Denemark, & Western, 2005). Although much of the developed world provides structured antenatal education for childbearing women and their partners, these programs often have not been based on the express needs of attendees, but rather on the messages that the educators themselves believe they should impart (Gagnon & Sandall, 2000; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2007). More research is needed to facilitate understanding of the impact of the midwife/woman relationship in preparing for birth and motherhood. Likewise, although midwives recognize that the stories expectant women hear from other women, particularly from mothers and sisters, have a significant impact on women, these sources of information for pregnant women receive brief attention in the professional literature.

Evidence suggests that women select their place of birth according to the level of choice and responsibility they wish to take in the birth: Women who choose out-of-hospital care tend to want more control over decisions regarding themselves, their bodies, and the birth environment compared with women who choose hospital care (Cohen, 1981; Fullerton, 1982; Fullerton & Severino, 1992; Hodnett, Downe, Edwards, & Walsh, 2005; Neuhaus, Piroth, Kiencke, Göhring, & Mallman, 2002). It is likely that preparations for the birth in the different environments of home and hospital also vary because the relationship between the woman and her caregiver is often dissimilar in the two environments.

The aim of this research was to explore the experience of a small group of first-time mothers giving birth at home or in hospital. This article focuses on the preparation for the birth undertaken by these women. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant human ethics committees before the commencement of the study.

METHODS

A grounded theory approach was chosen because its objective is to explain basic patterns common in social life. A grounded theory approach requires that the researcher look for contradictions and contrasts, as well as similarities, to confirm analysis (Chenitz & Swanson, 1986; Glaser & Strauss, 1980; Moghaddam, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Grounded theory is essentially an inductive strategy for generating and confirming theory that emerges from close involvement and direct contact with the empirical world (Patton, 1990).

Participants

Nineteen women participated in the study. They were recruited using purposive and theoretical sampling. Purposeful sampling occurs where the phenomenon is known to exist (Patton, 1990). Theoretical sampling is the process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes, and analyzes the data, and decides what data to collect next and where to find them in order to develop the theory as it emerges. Unlike statistical sampling, theoretical sampling cannot be predetermined prior to the outset of the study, and sampling decisions emerge as the study progresses (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This means that the researcher deliberately samples the data to discover more ideas and connections. For example, in the present study, we decided we needed to interview women who had had a baby previously and women who had had births in venues other than home and public hospital (birth center and private hospital).

Women who had given birth to their first baby were initially identified in the postnatal ward of a large tertiary referral hospital and asked to consent to being interviewed 6 weeks later. Women who had their first baby at home were contacted by their independent midwives and asked if they could be approached to participate. One first-time mother who had given birth in a private hospital, two first-time mothers who had given birth in a birth center, and two multiparous women (one hospital birth and one home birth) were also identified and invited to participate. Each potential participant received an information sheet that explained the purpose of the study and what would be required of participants. Each participant signed a consent form. Only one woman (planned hospital birth) chose not to participate.

Data Collection

Data were generated from in-depth interviews with the mothers in their own homes. The interviews lasted from 20 minutes to 3 hours. The interviews were audiotaped and fully transcribed. Open-ended questions were used during the interviews and were altered while data were gathered and analyzed, as is appropriate with grounded theory. The interviews eventually became highly selective and more focused on particular topics and, consequently, shorter (Dey, 1999). The interviews were conducted between 6 and 26 weeks after the birth, with a mean of 15 weeks. Women who had given birth at home were generally interviewed a few weeks later than those who had given birth in hospital, because they were more difficult to access. In this article, the women and all names in the quotes are assigned pseudonyms for the purposes of presenting the results.

Data Analysis

In a grounded theory analysis, the researcher's aim is to discover the dominant themes and develop a conceptual framework that underpins theorizing (Glaser & Strauss, 1980). The interrelationships between these themes are explored and tested using deeper analysis, and theories about them are formed. Coding is used in grounded theory and is defined as the analytical process through which data are fractured, conceptualized, and integrated to form a theory (Moghaddam, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Three types of coding are used in grounded theory: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding.

In the present study, open coding involved identifying, naming, categorizing, and describing the phenomena. Transcripts were broken down into lines and phrases and paragraphs, and these discrete concepts were labeled. The labels often consisted of the words used by the women to ensure that their original meaning was maintained.

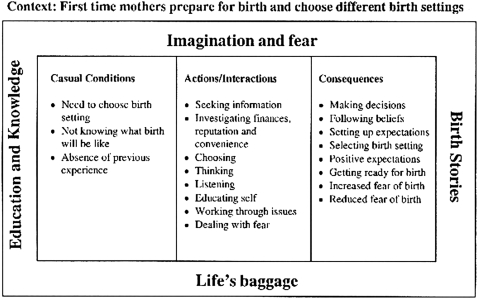

Open coding was followed by axial coding, which essentially reassembles the data that are fractured by open coding and involves relating categories and properties to each other—that is, interpreting and grouping (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Similar concepts were examined, compared, and grouped into categories to distinguish their properties and dimensions. Data collection and analysis continued until the categories were “saturated” and no new concepts were obtained (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Memo writing and the use of diagrams were also incorporated as essential parts of the analysis. This approach helped incorporate interaction and process. We also examined causal conditions and the context in which categories were embedded, as well as the intervening conditions, which we termed “mediating factors” (Barclay, Everitt, Rogan, Schmied, & Wyllie, 1997), and the consequences.

Finally, we undertook selective coding, which is the process of choosing one category to be the core category and relating all the other categories to that category (Strauss & Corbin, 1997). The idea of selective coding is to develop a single storyline around which everything else is arranged. A basic social process was identified that linked and described the dynamism present in the data. This article reports on one of these categories, “Preparing for Birth.” The other categories, as well as a more detailed explanation of the methods used, are described more fully elsewhere (Dahlen, Barclay, & Homer, 2008).

We presented the results of the analysis to five of the women in the study and their midwives. All confirmed that the explanations seemed correct to them.

FINDINGS

The participants ranged from 19 to 37 years of age. Women who had had home births were on average 30 years old compared with 25 years old for the women who had had hospital births. All of the women had partners. Three women had university degrees (one in the home-birth group and three in the hospital-birth group). One of the home-birth women was transferred to hospital and had a forceps birth. All of the women who gave birth in hospital—except for one (forceps birth)—had normal vaginal births. Most of the women attended formal antenatal childbirth education (all of the home-birth group, and 5 of 8 in the hospital-birth group).

Three categories emerged from the analysis: “Preparing for Birth,” “The Novice Birthing,” and “Processing the Birth,” with the core category being The Novice Birthing (Dahlen et al., 2008). This article specifically addresses the category “Preparing for Birth.”

Preparing for Birth

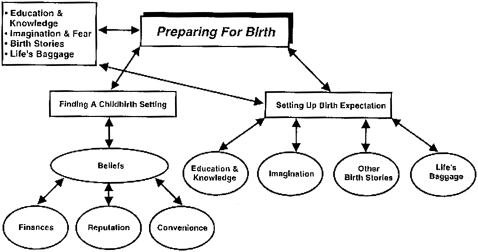

The category “Preparing for Birth” consisted of two subcategories, “Finding a Childbirth Setting” and “Setting Up Birth Expectations.” The mediating factors that were influential in the subcategories were beliefs, convenience, finances, reputation, imagination, education and knowledge, birth stories, and what was termed “‘life’s baggage” or “previous life experiences” (see Figure 1).

“Preparing for Birth” category, subcategories, and mediating factors

The interviewed women frequently referred to the period of preparation for the birth as having a significant influence on and being an important part of their entire birth experience. They acknowledged in their stories that it was during this period that they prepared to give birth. They did so by “finding a childbirth setting” and “setting up birth expectations” (subcategories). As one study participant noted, “I've had cats that used to have kittens in my childhood. You know an animal seeks out its place, and I think we are just animals in our own way, just slightly more evolved” (Kerry, home birth).

The women also prepared for their births by choosing a place to give birth. Although all of the women in this study prepared for birth, they did so in very different ways. Kerry, who had a home birth, attended two different antenatal classes, read Spiritual Midwifery (Gaskin, 2002) three times, and knew her subject amazingly well. Laura, who chose to give birth in hospital, did not know what a contraction was. It became evident early in the research that the women who gave birth at home invested a lot more time and energy in preparing for birth than did the women who gave birth in hospital.

Finding a childbirth setting

The venue in which women ultimately gave birth was a consequence of a number of important decisions. The women used the words “birth setting,” rather than “birth place.” When they chose a birth setting, they also made choices about their caregiver. The choice of a birth setting was most strongly influenced by the women's (a) “belief systems,” and secondarily influenced by (b) “convenience,” (c) “finances,” and (d) “reputation.” These factors were in turn mediated by the women's birth “education and knowledge,” “imagination,” “fears,” other women's “birth stories,” and past experiences (see Figure 2). The past experiences are labeled “life's baggage,” using the women's words.

Mediating factors influencing first-time mothers' choice of birth setting

Belief systems

Before their pregnancy, none of the women who gave birth at home had initially planned to have a home birth. These women usually found that their needs could not be catered to in a hospital setting. Women who chose home birth did so as part of their focus on making decisions about their care. For example, May switched from a private obstetrician to an independent midwife and home birth when her choices could not be met. She noted, “I was not impressed with their [the hospital setting's] ability to deliver you only on the bed and nowhere else.” Tracy wanted to have a water birth. After approaching several hospitals and meeting resistance, she finally opted for a home birth. She commented, “None of them could say whether I could have a water birth. They weren't very supportive of the idea.”

Cultural beliefs also influenced the choice of birth setting. Elsa (from a non-English-speaking background) found that she could not be guaranteed a female caregiver in any of the hospitals she contacted. Finally, she chose a home birth. All of the women who eventually chose to give birth in their home did so because it catered to their beliefs and met their needs.

It is harder to follow the rationale of the women who chose hospital birth, because their decision was not explicit or conscious. That is, hospital birth was often not thought of or described as a choice, because no other option was considered. This rationale in itself, however, demonstrates the operation of a belief system. It also demonstrates a lack of accessible information on choices. Compared to the women who chose home birth, the women who chose hospital birth seemed less concerned about personal decision making, more dependent on their caregivers, and more trusting of the medical system. As two women noted:

Women who chose a home birth viewed medical interventions as negative and dangerous, while those who chose a hospital birth viewed medical interventions as positive:

The women in our study did not choose to give birth at home or in hospital because of the physical environment; rather, they chose the setting because of the philosophical underpinnings and the type of care in each setting.

Convenience

Convenience was another influence on the choice of the birth setting and appeared more influential for the women who chose a hospital birth than for the women who chose a home birth. Women tended to choose hospitals close to their homes. Some of the women who gave birth in hospital said the birth centers were too far away to be an option. For example, Bess (hospital birth) felt that convenience played a part in her choice of birth setting. The nearest birth center required a 20-minute drive and, as she reported, “My husband wasn't happy to drive to the birth center because it was too far.” It must also be noted, though, that Bess had previously stated she preferred medical care to midwifery care due to her being “wary” about giving birth to her first baby.

However, in other instances, convenience appeared secondary to beliefs in terms of the choice of childbirth setting. Women who really wanted to give birth in a birth center traveled great distances. For example, Jill (home birth) traveled many kilometers from her home in the outer western region of Sydney to an inner-city birth center. Although another birth center was closer, she wanted a particular midwife who did not attend that specific birth center. Thus, Jill's belief system appeared to overrule her desires for convenience.

Finances

In Australia, women can access care with an obstetrician of their choice if they have private health insurance. Public health services, through the public health insurance model known as Medicare, entitle all women to hospital-based maternity care provided by hospital-employed midwives and doctors. If women wish to access independent midwives, they must meet all the costs themselves, because private or public health insurers do not cover independent midwifery care.

For the participants in this study, finances played a small part in the women's choice of childbirth setting. Some of the women who gave birth in the public hospital system said they would have preferred private obstetric care if they could have afforded it. When this viewpoint was explored further during interviews, the reason given was to ensure continuity of care rather than to purchase private medical care itself. Private insurance seemed to be the only way to guarantee continuity of care in the hospital system. As Bess (hospital birth) noted, “Some people say you pay thousands of dollars to see a gynecologist and they're never there anyway, but at least you know you see the same person every time you go to have a check up.”

Not all of the women who gave birth at home could easily afford the midwife's fee, and they struggled financially to achieve their choice of childbirth setting. In general, however, the home-birth women had higher incomes than the hospital-birth group. Ultimately, their financial situation was less important than their beliefs concerning their birth setting.

Reputation

The reputation of the hospital and the midwife also played a role in the choice of birth setting. Women who had a hospital birth had already decided to give birth in hospital and were looking for a place with a good reputation. A general practitioner or friends usually recommended the hospital. According to Anita (hospital birth), “My friends told me it was a good hospital and you should go there.”

It is interesting that women who chose to give birth at home often finally decided on a home birth on the basis of the reputation or knowledge of the midwife. For example, the following women explained their decision to give birth at home:

The women made decisions and prepared for birth as novices (Dahlen et al., 2008). They often talked about their fears, lack of knowledge, and dependence on more experienced family friends and health professionals for advice. Ebony, who gave birth in hospital, said, “I really wasn't very aware of the other options.” Ebony was “faced with this choice,” and “the people” around her “had just gone to hospital and had an obstetrician deliver their baby.” Ebony “didn't know what the options were” and “didn't know where to go to.” At the end of the day, “it [the choice of options] was completely unknown” to her.

Setting up birth expectations

When the women were asked to describe their birth experiences, they tended to include the preparation stage as part of the experience as a whole. They referred back to the expectations they had set up and how their expectations affected the birth. They indicated that along with “finding a childbirth setting,” their preparation for birth included “setting up birth expectations.” As first-time mothers, the women lacked real-life, personal experience with giving birth. Consequently, their reported birth expectations drew on the women's (a) “imagination,” (b) “education and knowledge,” (c) other women's “birth stories,” and (d) “life's baggage.”

Imagination

When recalling their thoughts about the pending birth experience, the women in the study reported imagining both positive and negative scenarios for themselves. They often used the words “imagination” or “imagine” when describing their expectations. As first-time mothers, they had no prior, personal experiences of birth to draw on and so tended to describe the process of creating expectations through imagination.

Fear was evident as an undercurrent in the women's imagining during this period and was often linked to pain. The women reported focusing on pain as they analyzed their own past experiences of pain and questioned their abilities to cope. Sarah (hospital birth) expected the pain to be bad, based on birth stories she had heard and on her imagination:

On the other hand, Laura (hospital birth), who had seen both her sisters give birth, “never imagined having bad pain.” Her overriding, negative memory of her labor was the pain. Of all the interviews conducted, Laura almost “painted” the pain. Her distress was still evident when she was interviewed 8 weeks after giving birth: “I couldn't put in my mind what pain I would suffer…. It was the worst pain I've ever had in my life. I can see the pain, you know. Not feel it, I can see it.”

Although images of pain and the deliberation over whether they would be able to handle pain predominated in the women's imagination, study participants also expressed fears for their baby or for themselves. Participants often reported imagining that their baby might be “abnormal.” Bess's (hospital birth) imagination became so vivid that when she first saw her baby, she thought it was abnormal: “I was very scared. I didn't know what I was expecting. My fear was my baby. If my baby was going to be normal.” Bess also recounted:

For one woman, imagination about the birth extended to the concept of dying during childbirth: “I was very afraid. Worse than even labor, I thought I could even die” (Anita, hospital birth).

The women who gave birth in hospital had imagined more negative events and seemed to have been more fearful than the women who gave birth at home. The home-birth women had addressed their fears and developed more realistic expectations prior to giving birth. This form of preparation seemed to be due to their strong motivation to inform themselves in advance about the birth experience. Midwives had instilled these women with confidence in their abilities to give birth, and the women reported having spent large amounts of time with the midwife, who provided education and answered questions.

Education and knowledge

The women in the study who gave birth at home reported they had attended antenatal classes and had also participated in pain-management classes, yoga, or more than one antenatal class, which influenced their birth expectations. For example, in the following interview excerpts, Kerry (home birth) described her progress from negative to positive expectations of birth, primarily through education:

Kerry had prepared herself and dealt with her fears, enabling her to go into the birth with an “open” and positive attitude. Her confidence in her preparation, her sense of personal control, and her reduced levels of anxiety set her up for the positive birth she expected and, ultimately, experienced. Women in the study who gave birth at home had set high expectations, and all but one was extremely satisfied.

The nature and type of education that influenced birth expectations was different across settings and individuals. Furthermore, the women's perceptions of their personal needs for education varied. For example, in contrast to Kerry's (home birth) expectations and educational experiences described above, Nancy (hospital birth) expressed no expectations of her birth experience, offered no specific comments about it, and said she was satisfied overall. At 19 years old, Nancy was relaxed, obviously quite unconcerned, and gave the shortest interview (duration of 20 minutes) among all the study's participants. She had little to say about her labor experience, except that it appeared “okay” and not as bad as she thought it would be. Perhaps having no expectations meant she had no chance to be disappointed. Nancy noted, “I was told if you have expectations, you feel like you let yourself down if you go against what you've expected.”

Birth stories

The birth stories that seemed to have the most impact on the women in this study came from their mothers and sisters. Women having their first baby talked about the close bond they developed with their mothers and sisters, especially during pregnancy. Study participants also reported that if their partner was not available to attend antenatal childbirth classes, their mothers and sisters often accompanied them. Mothers and sisters were important in the study participants' lives, and the birth stories these family members related became incorporated into the expectant mothers' preparations for birth and their expectations of how their own bodies would perform.

Women in the study commented that most of their family members' birth stories were negative, which influenced the study participants' birth preparations and expectations. For example, Wanda (home/hospital birth) had incorporated her mother's and her grandmother's birth experiences and felt her own experience would follow a similar pattern. She noted, “I didn't think it was going to be quick and easy. I think from my mother and grandmother. I spoke to them.” Another study participant provided similar insight into the influence of her mother's and sister's birth stories on her own births:

Likewise, Kerry (home birth) was influenced by her mother's negative birth stories and worked very hard to overcome her fears based on her mother's accounts. Later, Kerry encouraged her sister to attend her birth and antenatal classes and made sure the experience was positive for her sister because she had not given birth before. The study participants commented that although most of the stories they had heard were negative, they were now making an effort to tell positive birth stories to their pregnant friends.

Women in the study reported another type of storytelling. Medical practitioners became involved in dramatic storytelling when confronted with women who chose to give birth at home. Doctors told the women of the dangers of home birth, and their stories were often accompanied by inaccurate statistics. For example, May reported that a doctor claimed all babies died when born at home. Tracy's doctor told her that 30% of babies who are born at home die. Elsa spent the first part of her pregnancy in fear of a jail sentence when her medical practitioner told her it was against the law to have a home birth and that she might be arrested. None of the health-care providers' stories was true.

Dealing with life's baggage

As a whole new area of life unfolded for the women and they prepared to become mothers, some of them appeared to go through a period of self-growth. Kerry (home birth) labeled this growth “dealing with life's baggage.” Pregnancy was a time of looking forward to and preparing for motherhood, but it also appeared to be a time of looking back and analyzing who they were and what kind of mothers they would be in relation to a prior identity.

Kerry (home birth) dealt with many emotional issues during her pregnancy and found it a time of tremendous growth. She realized she needed to address issues that might “block” her during the birth. She became aware that, as she was about to become a mother, she had to face her own grief about her mother:

Not all of the women wanted to analyze their past and deal with emotional issues, and not all of them were successful in attaining this goal. Wanda (home/hospital birth) had always done things for others and, when she came to give birth, she reverted to this pattern and tried to give birth to please others rather than follow her own instincts and needs. Wanda said she learned much from the experience, though it was painful:

Home-birth midwives and home-birth mothers' educational programs encourage self-analysis and self-growth. Therefore, it is not surprising that, compared to the hospital-birth women, more home-birth women in this study went through the process of dealing with “life's baggage.”

DISCUSSION

The women in this study prepared for birth in many different ways and with varying intensity. They prepared for birth to help them manage the unknown and equip them as they faced the coming birth as “novices.” They prepared for their births by “finding a childbirth setting” and “setting up birth expectations.” These women selected their childbirth setting based mostly on their “beliefs.” They set up expectations through “imagination,” “education and knowledge,” “birth stories,” and dealing with any of “life's baggage” that they or their midwives perceived might block them during the birth and later on as mothers. Women who chose home birth spent more time examining their options, seemed better prepared overall for birth, and had higher expectations than women who chose hospital birth. Women in the hospital-birth group generally reported feeling less prepared for birth and were more likely to be disappointed by the experience compared with women in the home-birth group who, even though their expectations were high, mostly had their expectations realized.

A systematic review in the Cochrane Library concluded that the effects of general antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both, remain largely unknown (Gagnon & Sandall, 2000). The authors reported that women might attend antenatal classes to reduce anxiety about labor and birth. A recent study in Australia indicated that women attending a special program designed to meet expectant and new parents' needs, as identified by the parents, was successful in improving maternal self-efficacy and perceived parenting scores (Svensson et al., 2007). An important feature of this program (titled “Having a Baby”) was recognizing that pregnancy, labor, birth, and early parenting are parts of the complete childbearing experience rather than separate topics (Svensson et al., 2007). In the present study, women did not identify antenatal education as being a prime source of their knowledge and preparation for the birth; rather, they saw it as part of a wider, more complex package of strategies. This could be because the women were not specifically asked about this aspect. The women were more likely to describe the influence of family and friends on their preparations for birth than the influence of antenatal classes. Although researchers have rightly described a shift in the way women obtain knowledge from female friends or mothers to television programs, childbirth classes, and the Internet (Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, & Tarule, 1997; Romano, 2007; Savage, 2006; Zwelling, 1996), data from the current study show that female friends and relatives still have a significant influence on expectant mothers' childbirth preparation and the expectations they form; thus, health professionals should further explore this influence.

Others have argued that valuing professional knowledge over that of women has fractured traditional knowledge systems (e.g., woman to woman) and accelerated their replacement by technology. Authoritative knowledge has superseded personal knowing in many developed countries, which leads to minimizing a woman's knowledge of her own bodily functions. As women distrust their intuition regarding their ability to give birth, they tend to embrace authoritative knowledge more readily (Savage, 2006). In the current study, women who planned a home birth were encouraged by their midwives to trust in their own ability to give birth. The midwives worked with the women on issues they felt would block the women's belief in themselves. In the hospital-birth group, women were more likely to view health professionals, particularly the doctor, as authoritative, and their care was mostly fragmented.

Women in this study who gave birth at home and in birth centers chose independent midwives to be their caregivers. Women who chose the public hospital setting received a combination of medical and midwifery caregivers. Most of the women selected their birth setting not for the physical environment but for the philosophies and caregivers associated with that environment and what felt safe for them. Home-birth women tended to feel that the medical models dominant in the hospital system would be restrictive and potentially unsafe for them and their baby, while hospital-birth women thought this model was likely to provide the greatest safety. Women who chose out-of-hospital care were more likely to want control over decision-making situations, their bodies, and the birth environment compared to women who chose traditional hospital care. This finding is supported by other research outcomes (Cohen, 1981; Fullerton, 1982; Fullerton & Severino, 1992; Hodnett et al., 2005; Neuhaus et al., 2002).

Rubin (1984) contends that, from the onset of labor to the birth, childbearing involves women exchanging a known self in a known world with an unknown self in an unknown world. The first birth experience is very significant to women, and they have high expectations. Other researchers report varying responses from primigravid and multigravid women, particularly regarding primigravid women's unrealistic expectations, fear, and anxiety (Beaton & Gupton, 1990; Berry, 1988; Kearney & Cornenwett, 1989; Stolte, 1987). First-time mothers may set up unrealistic expectations for several reasons: They have no previous experience on which to draw, and they do not have appropriate preparation, information, communication, or support.

Preparation for birth needs to enhance the woman's sense of confidence by providing accurate and realistic information that will enable her to make informed choices and decisions and allow her to feel in control of her labor and birth (Enkin et al., 2000; Gibbins & Thomson, 2001). In the present study, the women in the home-birth group felt that their midwives helped prepare them not only for birth, but also for motherhood. This helped diminish their fears and increase their trust, making the unknown more acceptable. Compared to women in the home-birth group, women in the hospital-birth group were less likely to seek out childbirth education and did not have the same supportive midwifery care. This made the unknown more frightening and out of their control.

Support from midwives (Flint, Poulengeris, & Grant, 1989) and from other significant people in a woman's life (Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2007; Lavender, Walkimshaw, & Walton, 1999) contributes to more positive birthing experiences. In the current study, women in the home-birth group appeared to gain many benefits from the continuity-of-care relationship they developed with their midwives. Preparation for birth was particularly enhanced by this ongoing professional relationship. Planning for future maternity services should have midwifery continuity of care as a goal. This can be achieved in a variety of ways in and out of hospital. Currently, fewer than 5% of women experience midwifery continuity of care in Australia, despite numerous supportive government reports (Hirst, 2005; National Health and Medical Research Council, 1996, 1998; Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 1999).

The present study contains limitations. All of the women spoke fluent English and, therefore, cultural contexts were not explored. A larger number of multiparous women should be interviewed to more fully contrast the experience of this group with that of first-time mothers, especially women with less positive previous birth experiences. This study's sample was obviously not a matched or representative sample, and there were significant differences in socioeconomic status, age, and antenatal preparation between the participants, which reflected the women's selection of care models and their experience of birth. All of these factors can have an impact on the birth experience. The experiences of the women in this study may not be representative of all women giving birth in Australia. However, their experiences were found to be credible to other women experiencing first births and to the midwives who care for them.

Research into factors that contribute to a positive or negative first birth is now underway. Ongoing and future investigations will build on and further validate the findings of this study.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the birth experiences of Australian first-time mothers in the settings of home and hospital, and its findings can help midwives understand how birthing women, particularly first-time mothers, prepare for birth. Investigating birth experiences in different settings exposes similarities and differences in women's needs and experiences. The first-time mothers in our study all experienced birth as “novices,” yet they told very different stories and undertook different levels of preparation. Overall, the women who gave birth at home seemed more prepared for birth than the women in the hospital-birth group and were supported by midwives who they knew and who spent time discussing the issues that are important to women when becoming mothers. The impact of birth stories of expectant women's mothers and sisters on women's expectations and preparation for birth appears to be underestimated and should be addressed by health providers during the pregnancy.

Footnotes

On the deepest level, I knew nothing of what was to happen. I just seemed to spill out circular, a boundless belly. In my mind however I knew everything, or so I thought. In the manner of the day, I had read all the books and attended two sets of classes, dedicatedly practicing to confront the unknowable. (Dell'oso, 1989, p. 190)

On the deepest level, I knew nothing of what was to happen. I just seemed to spill out circular, a boundless belly. In my mind however I knew everything, or so I thought. In the manner of the day, I had read all the books and attended two sets of classes, dedicatedly practicing to confront the unknowable. (Dell'oso, 1989, p. 190)

…It didn't bother me. It's just as long as he was healthy. (Nancy, hospital birth)

…It didn't bother me. It's just as long as he was healthy. (Nancy, hospital birth)

I didn't go through the midwives only because it was my first baby and I was wary. So I thought I would go through a doctor. (Bess, hospital birth)

I didn't go through the midwives only because it was my first baby and I was wary. So I thought I would go through a doctor. (Bess, hospital birth)

They [hospital staff] were there if I needed help, so I felt pretty secure there [hospital]. (Nancy, hospital birth)

They [hospital staff] were there if I needed help, so I felt pretty secure there [hospital]. (Nancy, hospital birth)

You'd have a better chance of it being natural, a natural type of birth at home, than you would in hospital. (Leanne, home birth)

You'd have a better chance of it being natural, a natural type of birth at home, than you would in hospital. (Leanne, home birth)

I just looked at her [the midwife] and thought what an amazing woman, and she just gave me a big hug and I gave her a hug. So even before becoming pregnant, I had chosen her. I knew I would have her. (Kerry, home birth)

I just looked at her [the midwife] and thought what an amazing woman, and she just gave me a big hug and I gave her a hug. So even before becoming pregnant, I had chosen her. I knew I would have her. (Kerry, home birth)

I don't know if I would have had a home birth if I hadn't known Gail [the midwife]. (Meg, home birth)

I don't know if I would have had a home birth if I hadn't known Gail [the midwife]. (Meg, home birth)

Awful! I really expected it to be extremely painful because Mum said her labor was 23 hours for her first, which was me, and I was really scared. But it wasn't as bad as I thought it was going to be.

Awful! I really expected it to be extremely painful because Mum said her labor was 23 hours for her first, which was me, and I was really scared. But it wasn't as bad as I thought it was going to be.

And he [my husband] says to the nurse, “Are his hands okay?” And he says, “Has he got five fingers?” And as soon as he said that, I said, “I'm not looking, you count them.” It was just too frightening because this was my fear, and I thought, “Is it coming to reality?”

And he [my husband] says to the nurse, “Are his hands okay?” And he says, “Has he got five fingers?” And as soon as he said that, I said, “I'm not looking, you count them.” It was just too frightening because this was my fear, and I thought, “Is it coming to reality?”

I had a lot of fear around pain and what I considered to be this maiming experience of birth.

I had a lot of fear around pain and what I considered to be this maiming experience of birth.

I didn't read anything for 9 months except birthing books, I swear. I mean, I just studied it. I knew it so well that the birthing classes suggested that I become a teacher.

I didn't read anything for 9 months except birthing books, I swear. I mean, I just studied it. I knew it so well that the birthing classes suggested that I become a teacher.

By the time I was in preparation for her birth, I had a lot of very, very positive expectations around the birth. I envisioned love around me and my own environment. To have all the things that I wanted, like music and the candles and the aromatherapy and my sister and husband and Amy [midwife].

By the time I was in preparation for her birth, I had a lot of very, very positive expectations around the birth. I envisioned love around me and my own environment. To have all the things that I wanted, like music and the candles and the aromatherapy and my sister and husband and Amy [midwife].

They both had really terrible first deliveries, and Mum said she was in labor for 3 days and 3 nights and no one came near her. She had her first baby in 1950-something. Then, when my older sister had her first baby, she had a pretty bad time too, and I thought, “Well, I'll probably have a bad time first time round….” (Meg, home birth for second child)

They both had really terrible first deliveries, and Mum said she was in labor for 3 days and 3 nights and no one came near her. She had her first baby in 1950-something. Then, when my older sister had her first baby, she had a pretty bad time too, and I thought, “Well, I'll probably have a bad time first time round….” (Meg, home birth for second child)

…[A] lot of the grief I went through was around my mother, around the fact she couldn't recollect my own birth, that she'd never been able to tell me anything about it [twilight sleep]; about the fact that my mother is suffering dementia.

…[A] lot of the grief I went through was around my mother, around the fact she couldn't recollect my own birth, that she'd never been able to tell me anything about it [twilight sleep]; about the fact that my mother is suffering dementia.

…I thought I had done that and got to that point that I had resolved that in my life and started doing that on so many levels, yes, but what came up for me was hugely no. I was still doing things for others.

…I thought I had done that and got to that point that I had resolved that in my life and started doing that on so many levels, yes, but what came up for me was hugely no. I was still doing things for others.

REFERENCES

- Barclay L, Everitt L, Rogan F, Schmied V, Wyllie A. Becoming a mother – An analysis of women's experience of early motherhood. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(4):719–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-1-1997025719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian H, Keirse M. J, Lancaster P. Perinatal death associated with planned home birth in Australia: Population based study. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7155):384–388. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7155.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton J, Gupton G. Childbirth expectations: A qualitative analysis. Midwifery. 1990;6(3):133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(05)80170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky M, Clinchy B, Goldberger N, Tarule J. 1997. Women's ways of knowing: The development of self, voice and mind. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berry L. Realistic expectations of the labor coach. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1988;17(5):354–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1988.tb00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Macfarlane A. 1994. Where to be born? The debate and the evidence (2nd ed.). Oxford, U.K.: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit.

- Chenitz W. C, Swanson J. M. 1986. From practice to grounded theory: Qualitative research in nursing. Menolo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Cliff D, Deery R. Too much like school: Social class, age, marital status and attendance/non-attendance at antenatal classes. Midwifery. 1997;13(3):139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(97)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R. L. Factors influencing maternal choice of childbirth alternatives. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1981;20(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen H, Barclay L, Homer C. 2008, April 3. The novice birthing: Theorising first-time mothers' experiences of birth at home and in hospital in Australia [E-pub ahead of print; doi:10.1016/j.midw.2008.01.012]. Midwifery.

- Dell'oso A. M. 1989. Cats, cradles and camomile tea. Sydney, Australia: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dey I. 1999. Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enkin M, Keirse M. J. N. C, Neilson J. P, Crowther C. A, Duley L, Hodnett E. D. 2000. A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth (3rd ed. et al. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian H, Rådestad I, Waldenström U. Childbirth and parenthood education classes in Sweden. Women's opinion and possible outcomes. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2004;84:436–443. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint C, Poulengeris P, Grant A. The “know your midwife” scheme – A randomised trial of continuity of care by a team of midwives. Midwifery. 1989;5(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(89)80059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton J. The choice of in-hospital or alternative birth environment as related to the concept of control. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1982;27(2):17–22. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(82)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton J, Severino R. In-hospital care for low-risk childbirth: Comparison with results from the National Birth Center Study. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1992;37(5):331–340. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(92)90240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A. J, Sandall J. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. 2000. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 4, Art. No.: CD002869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gaskin I. M. 2002. Spiritual midwifery. Cambridge, U.K.: Summertown. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins J, Thomson A. M. Women's expectations and experiences of childbirth. Midwifery. 2001;17(4):302–313. doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilding M. Changing families in Australia 1901–2001. Family Matters. 2001;60(Spring/Summer):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G, Strauss A. L. 1980. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst C. 2005. ReBirthing: Report of the Review into Maternity Services in Queensland. Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. D, Downe S, Edwards N, Walsh D. M. Home-like versus conventional institutional settings for birth. 2005. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 1, Art. No.: CD000012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hodnett E. D, Gates S, Hofmeyr G. J, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. 2007. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 2, Art. No.: CD003766. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johnson K. C, Daviss B. Outcomes of planned home births with certified professional midwives: Large prospective study in North America. British Medical Journal. 2005;330:1416–1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7505.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M, Cornenwett L. Perceived perinatal complications and childbirth satisfaction. Applied Nursing Research. 1989;2(3):140–142. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(89)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender T, Walkimshaw S. A, Walton I. A prospective study of women's views of factors contributing to a positive birth experience. Midwifery. 1999;15(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(99)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws P, Abeywardana S, Walker J, Sullivan E. 2007. Australia's mothers and babies 2005. Sydney, Australia: AIHW [Australian Institute of Health and Welfare] National Perinatal Statistics Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J, Brown S. Attenders and nonattenders at childbirth education classes in Australia: How do they and their births differ? Birth. 1993;20(3):123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1993.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam A. Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues in Educational Research. 2006;16(1):52–66. Retrieved August 9, 2008, from http://www.iier.org.au/iier16/moghaddam.html. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 1996. Options for effective care in childbirth. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Printing Service. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 1998. Review of services offered by midwives. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2007. Intrapartum care: Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus W, Piroth C, Kiencke P, Göhring U. J, Mallman P. A psychosocial analysis of women planning birth outside hospital. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2002;22(2):143–149. doi: 10.1080/01443610120113274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M. R. Adjustment to new parenthood: Attenders versus nonattenders at prenatal education classes. Birth. 1995;22(1):21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1995.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Romano A. A changing landscape: Implications of pregnant women's Internet use for childbirth educators. Journal of Perinatal Education. 2007;16(4):18–24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. 1984. Maternal identity and the maternal experience. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. The lived experience of knowing in childbirth. Journal of Perinatal Education. 2006;15(3):10–24. doi: 10.1624/105812406X118986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senate Community Affairs References Committee. 1999. Rocking the cradle: A report into childbirth procedures. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Stolte K. A comparison of women's expectations of labor with the actual event. Birth. 1987;14(2):99–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1987.tb01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. 1997. Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. 1998. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J, Barclay L, Cooke M. The concerns and interests of expectant and new parents: Assessing learning needs. Journal of Perinatal Education. 2006;15(4):18–27. doi: 10.1624/105812406X151385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J, Barclay L, Cooke M. 2007, April 24. Randomised-controlled trial of two antenatal education programmes [E-pub ahead of print; doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.12.012]. Midwifery.

- Tracy S. K, Dahlen H, Caplice S, Laws P, Yueping A, Tracy M. Birth centers in Australia: A national population-based study of perinatal mortality associated with giving birth in a birth center. Birth. 2007;34(3):194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00171.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson H. Outcomes of 1001 midwife-attended home births in Toronto, 1983–1988. Birth. 1991;18(1):14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Meagher G, Gibson R, Denemark D, Western M. 2005. Australian social attitudes: The first report. Eds. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwelling E. Childbirth education in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(5):425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]