Abstract

Background

Much controversy exists regarding the clinical efficacy of behavioural and developmental interventions for improving the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). We conducted a systematic review to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of behavioural and developmental interventions for ASD.

Methods and Findings

Comprehensive searches were conducted in 22 electronic databases through May 2007. Further information was obtained through hand searching journals, searching reference lists, databases of theses and dissertations, and contacting experts in the field. Experimental and observational analytic studies were included if they were written in English and reported the efficacy of any behavioural or developmental intervention for individuals with ASD. Two independent reviewers made the final study selection, extracted data, and reached consensus on study quality. Results were summarized descriptively and, where possible, meta-analyses of the study results were conducted. One-hundred-and-one studies at predominantly high risk of bias that reported inconsistent results across various interventions were included in the review. Meta-analyses of three controlled clinical trials showed that Lovaas treatment was superior to special education on measures of adaptive behaviour, communication and interaction, comprehensive language, daily living skills, expressive language, overall intellectual functioning and socialization. High-intensity Lovaas was superior to low-intensity Lovaas on measures of intellectual functioning in two retrospective cohort studies. Pooling the results of two randomized controlled trials favoured developmental approaches based on initiative interaction compared to contingency interaction in the amount of time spent in stereotyped behaviours and distal social behaviour, but the effect sizes were not clinically significant. No statistically significant differences were found for: Lovaas versus special education for non-verbal intellectual functioning; Lovaas versus Developmental Individual-difference relationship-based intervention for communication skills; computer assisted instruction versus no treatment for facial expression recognition; and TEACCH versus standard care for imitation skills and eye-hand integration.

Conclusions

While this review suggests that Lovaas may improve some core symptoms of ASD compared to special education, these findings are based on pooling of a few, methodologically weak studies with few participants and relatively short-term follow-up. As no definitive behavioural or developmental intervention improves all symptoms for all individuals with ASD, it is recommended that clinical management be guided by individual needs and availability of resources.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a triad of deficits involving communication, reciprocal social interaction, and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests and activities [1]. In addition to these core features, a range of other behaviour problems are common, such as anxiety, depression, sleeping and eating disturbances, attention issues, temper tantrums, and aggression or self-injury [2]. Autism is classified within a clinical spectrum of disorders known as pervasive developmental disorders, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. The spectrum includes conditions such as Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, Atypical Autism, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified [3]. In clinical practice, professionals may use different terms interchangeably to refer to children with similar presentations. While there are no definitive medical tests to indicate the presence of any form of ASD, diagnosis can be made by three years of age based on the presence or absence of specific behaviours that are used as diagnostic criteria. Prevalence estimates indicate that between 10 and 15 of every 10,000 children are autistic [1], [4] but possibly greater than 20 of every 10,000 children have dysfunction which warrants diagnosis at any point along the spectrum [5], [6]. Common comorbidities include mental retardation (Intelligence quotient (IQ) <70) and epilepsy, which are associated with 70% and 25% of autism cases, respectively [7], [8]. While no known cure for ASD exists, the general agreement is that early diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment can improve outcomes in later years for most individuals [9]. Consequently, the question of how various interventions may help to increase the individual’s ability to function is highly relevant to families, health professionals, and policy makers.

Over the past 20 years, a variety of therapies have been proposed to improve the symptoms associated with ASD. Current treatments include pharmacological therapies and various complementary therapies including diet modifications, vitamin therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy and behavioural and developmental approaches [10]. Interventions that fall within the continuum of behavioural and developmental interventions have become the predominant treatment approach for promoting social, adaptive and behavioural function in children with ASD based on efficacy demonstrated in empirical studies. These interventions may be viewed in terms of their position on a continuum from highly structured discrete trial training behavioural approaches guided by a therapist, to social pragmatic approaches where teaching follows the child’s interests and is embedded in daily activities in a natural environment. While therapy may be provided for up to 40 hours per week, controversy exists regarding the intensity required to achieve positive outcomes and the efficacy of one approach compared to another. An umbrella review of systematic reviews of behavioural and developmental interventions for ASD [11] has found that most systematic reviews have methodological weaknesses which make them vulnerable to bias and compromise their validity. There is evidence of positive outcomes for many of the interventions examined in systematic reviews of ASD and therefore, there is a need for further systematic reviews on the effectiveness of behavioural and developmental interventions for ASD which adhere to strict scientific methods.

Clinicians, educators and families of individuals with ASD need to make informed decisions regarding treatment options and therefore, a host of clinical and research questions regarding the benefits of these interventions still need to be clarified and addressed. Considering the importance of, and demand for, behavioural interventions for ASD, as well as the current rising trend in new programs, a rigorous synthesis of high quality evidence regarding the effect of a continuum of behavioural and developmental interventions for ASD will provide much needed information for health care professionals, policy makers, researchers, and families. This systematic review was conducted in order to identify, appraise, and synthesize the evidence on the effects of a continuum of behavioural and developmental interventions for improving core symptoms associated with ASD.

Methods

Search Strategy

The systematic review followed a prospective protocol that was developed a priori. Peer-reviewed comprehensive searches were conducted up to May 2007 in 22 psychological, educational and biomedical electronic databases for commercially published literature, as well as dissertations, and conference abstracts (e.g., MEDLINE®, EMBASE, ERIC, CINAHL®, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, PsycINFO®, BIOSIS Previews®, and Web of Science®). We identified additional studies by contacting experts in the field and by searching reference lists of primary studies, review articles, and textbook chapters. Details of the complete search strategies are available in Supplement S1.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they were: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs) or observational analytical studies (i.e., prospective or retrospective cohort studies with comparison groups); published in English; and reported data on the effects of a behavioural or developmental intervention in individuals with ASD. Individuals with Rett's disorder or Childhood Disintegrative Disorder were not considered for this review as they do not conventionally fall within ASD due to their significantly different clinical course. Studies involving participants with dual diagnoses (i.e., any ASD plus attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, or learning problems) were also considered for inclusion. The primary outcome of interest was the change in core features of ASD (i.e., communication, reciprocal social interaction, and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests and activities) as indicated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria [1]. Other outcomes that were examined included changes in non-core behaviours, developmental changes, cognitive changes, adaptive behaviours, challenging behaviours, play skills, educational performance, and family-related outcomes. One reviewer screened titles and abstracts of potentially relevant studies. Inclusion criteria were applied independently by at least two reviewers. The primary reason for exclusion of articles was documented. A complete list of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are available in Supplement S2.

Quality Assessment and Data Abstraction

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. We assessed the methodological quality of the studies with two pre-tested checklists (one for clinical trials and the other for observational studies) that included items from other published scales and checklists [12]–[18]; these items address specific aspects of design, execution, and analysis of the studies. The trials checklist included questions related to bias reduction such as allocation concealment [19], [20], randomization, blinding (subject, provider, and outcome assessor blinding), and description of dropouts and withdrawals [21], [22]. Other variables that were evaluated included description of selection criteria, therapeutic regimens, intervention providers, and treatment fidelity. The checklist for the observational studies included items that evaluated the methods of selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts, ascertainment of outcome and exposure, and how the study handled confounders in the design or analysis. Finally, information regarding the source of funding was collected [23]. Information regarding the study design and methods, the characteristics of participants, interventions, comparison groups, and outcomes of interest were extracted using a pre-tested data extraction form. One reviewer extracted the data using a pre-tested form, and a second reviewer verified the accuracy and completeness of the data. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus between the data extractor and the data verifier. Interventions were categorized based on a classification scheme previously described by other researchers in this field [24].

Analysis and Presentation of Results

There is considerable overlap between and across various models to classify and describe interventions that fall within the continuum of behavioural and developmental interventions for ASD [25], [26]. Due to the absence of a unique classification system, an intervention taxonomy system was developed for the purposes of the review in order to categorize the interventions for the analysis. Each study that met the selection criteria was reviewed and classified according to the continuum of behavioural and developmental interventions described in the scientific literature. The coding categories were based, in part, on a classification scheme previously described by other researchers in this field [24]. Additional categories were added after consultation with a panel of experts. Two independent researchers coded each study. Coding was discussed between researchers on a study-by-study basis and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Results were summarized descriptively. Evidence tables were used to report information on study design, study population, treatment groups, outcomes, and results. Due to the limited number of interventions and outcomes available for meta-analysis, we attempted to identify patterns across individual study results. Where studies within an intervention category produced inconsistent results and conclusions, we examined the following variables to shed light on reasons for the discrepant findings: study design, length of follow-up, sample size, population characteristics (age, diagnosis), comparison, and outcomes.

We conducted a meta-analysis when two or more trials assessed the same intervention, used similar comparison groups, and had data for common outcomes of interest. If the same measure was reported, we used weighted mean differences (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); otherwise, we used standardised mean differences (SMD) and 95% CI. Hedges adjusted g was used as the standard deviation estimate for the SMD [27]. A SMD of 0.2 indicated a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect and 0.8 a large effect size [28]. Random effect models were used throughout to combine study results. If means or standard deviations were not reported, they were imputed from other information reported in the study. Heterogeneity was investigated using the chi-square test [29] and quantified with the I2 statistic [30]. Heterogeneity was characterized as small (I2 less than 25 percent), moderate (I2 between 26 and 74 percent) and high (75 percent and above) [30]. Sources of heterogeneity were explored qualitatively.

All the meta-analyses used endpoint data or change from baseline to endpoint data instead of using the average of separate mean changes calculated at different intervals of time. All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT® software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® for Windows® (SPSS® version 14.1, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and RevMan version 4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A 5-point change from baseline to endpoint was considered a clinically meaningful change [31].

Results

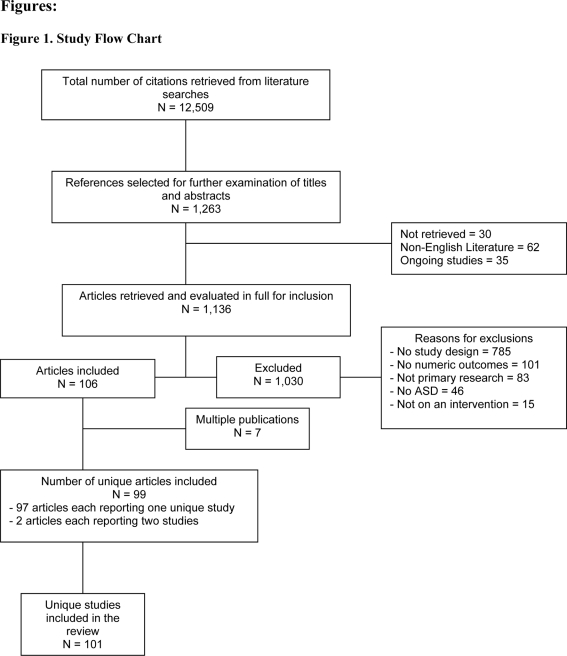

One hundred and one unique studies were included in the review. There were 55 RCTs, [32]–[83], 32 controlled clinical trials [84]–[115], four prospective cohort studies [116]–[119] and 10 retrospective cohort studies [120]–[129]. Figure 1 outlines the study flow for the review.

Figure 1. Study Flow Chart.

Description of Studies

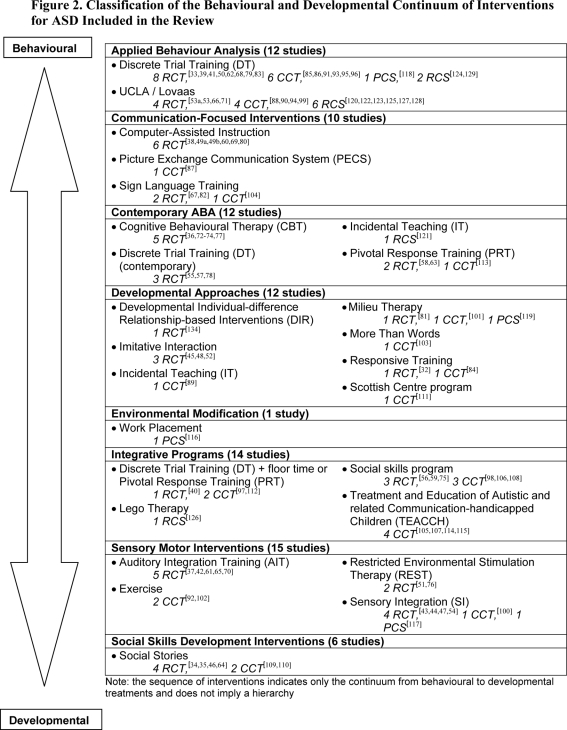

The studies evaluated the effect of eight broad types of interventions for ASD: Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) interventions, communication-focused interventions, contemporary ABA, developmental approaches, environmental modification programs, integrative programs, sensory motor interventions, and social skills development interventions (Figure 2). The studies were published between 1977 and 2007, with 2002 as the median year of publication. Data from a total of 2566 participants (median sample size = 22 per study; interquartile range: 15 to 36; n = 99) were reported in the studies. The median chronological age of participants in the studies was 62 months (interquartile range: 42 to 105 months; n = 84). Seventy-six percent of the studies included populations of infants or toddlers (less than 6 years of age), 44 per cent included school age children (6 to 12 years of age), 25 percent included adolescents (13 to 18 years of age), and only 11 percent included adults (older than 18 years of age). Studies included participants with conditions described as autistic disorder (93 percent), progressive developmental disorder (23 percent), Asperger’s syndrome (14 percent), high-functioning autism (5 percent), atypical autism (2 percent), not yet diagnosed autism (1 percent), and other (3 percent) such as autistic savant, or autistic-like conditions. The majority of the studies (67 percent) did not report on the level of severity of autistic symptoms in the study population. Participants with severe symptoms of ASD were included in 20 percent of the studies, whereas 19 percent included participants with moderate symptoms. Those with mild symptoms were not frequently included in the studies (15 percent). Summaries of the study characteristics and details of individual findings are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2. Classification of the Behavioural and Developmental Continuum of Interventions for ASD Included in the Review.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the review by type of intervention and study design.

| Study | Study design, duration | Age, diagnosis | Intervention | Comparison group | Author’s conclusions |

| APPLIED BEHAVIOUR ANALYSIS | |||||

| Discrete Trial Training | |||||

| Andrews E, 1998[33] USA | RCT Parallel 25 days | Age NR Autistic disorder | DT N = 3 | DT N = 3 | 1) An instructional model based on extra-stimulus prompts produced a significant improvement in measures of motor skills and learning ability. |

| Collier D, 1987[39] Canada | RCT Parallel NR | Age NR Autistic disorder | DT N = 3 | DT N = 3 | 1) The extra-stimulus prompt group performed significantly better in bowling than the within-stimulus prompt group in terms of task analytic level achieved. 2) Groups did not differ in reinforcements or punishments. |

| Dugan KT, 2006[41] USA | RCT Parallel 5 days | 58.9 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | DT N = 3 | DT N = 2 | 1) There were no significant differences between the use of picture activity schedules and prompting at home or at school in the rate of on-task behaviours. 2) There were no significant differences in the number of on-schedule behaviours between the groups. |

| SE N = 2 | |||||

| Harris SL, 1982[50] USA | RCT Cross-over 7 wk | 42.7 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 4 | WL N = 5 | 1) Behaviour modification training did not produce changes in parental speech oriented language. 2) There was no significant change in child speech after behaviour modification. |

| Nelson DL, 1980[62] USA | RCT Parallel NR | Age NR Autistic disorder | DT N = NR | DT N = NR | 1) The use of color-coded extra prompts does not accelerate the development of generalizable skills in daily living activities of autistic children. 2) This technique is probably inefficient in teaching shoe-lacing to autistic children. |

| Sherman J, 1988[68] Canada | RCT Parallel 8 mo | 62 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 5 | DT N = 5 | 1) Behavioural effects seem to favour the non-residential groups. 2) Non-residential groups demonstrated consistent improvements in functional behaviour. |

| DT N = 5 | |||||

| White SJ, 2000[79] USA | RCT Parallel 2 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, PDD | DT N = 15 | DT N = 15 | 1) Discrete trial therapy with negative feedback did not produce significant changes in the number of labels learned or the number of trials to reach criterion. 2) Discrete trial therapy with negative feedback produced a significant reduction of maladative behaviours. |

| Zifferblatt SM, 1977[83] USA | RCT Parallel 1 mo | Age NR Autistic disorder | DT N = NR | DT N = NR | 1) There were no significant differences between home generalization and school generalization in establishing generalization. |

| Bernard-Opitz V, 2004[85] Singapore | CCT Cross-over 10 wk | 38.8 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 4 | DIT N = 4 | 1) Behavioural and natural play interventions produced positive gains in play, attention, compliance, and communication. 2) Attendance and compliance was higher following the behavioural condition compared to play condition. |

| Birnbrauer JS, 1993[86] Australia | CCT Parallel 24 mo | 36.9 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | DT N = 9 | Control (ND) N = 5 | 1) Implementation of the Murdoch early intervention program can produce substantial gains in child functioning levels and parental stress in less than the ideal circumstances Lovaas described. |

| Elliott RO Jr, 1991[91] USA | CCT Parallel 8 wk | 312 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 11 | DIT N = 12 | 1) Both analog language teaching and natural language teaching increased initial and long-term generalization and retention. 2) Natural language teaching is strongly suported as preferable for people with autism and MR. |

| Harris SL, 1990[93] USA | CCT Parallel NR | 53.6 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 5 | LEAP N = 5 | 1) There were no significant differences in changes in language ability between the autistic children in the segregated and integrated class. |

| Howlin P, 1981[95] UK | CCT Parallel 6 mo | 70.9 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 16 | NT N = 16 | 1) Participants in the home-based language training program made significantly greater improvements in functional use of speech. 2) There were no significant difference between groups on language level at followup. |

| SC | |||||

| Hung DW, 1983[96] Canada | CCT Parallel 18 mo | 110.6 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 11 | SE N = 6 | 1) A systems-based educational program significantly improved functional skills in autistic children. 2) A systems-based educational program is significantly less expensive than a residential program. |

| SE N = 4 | |||||

| Residential N = 6 | |||||

| Pechous EA, 2001[118] USA | PCS 6 mo | 48.9 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 7 | NT N = 7 | 1) IBP significantly increased secured attachment behaviours and mothers’ sensitivity compared to no treatment. |

| Fenske EC, 1985[124] USA | RCS NR | 75.1 mo Autistic disorder | DT N = 9 | DT N = 9 | 1) There is a significant relationship between age at entry into a behavioural intervention program and positive treatment outcomes. |

| Tung R, 2005[129] USA | RCS NR | 70.6 mo Autistic disorder, PDD, High-functioning autism | DT N = 3 | NT N = 2 | 1) DT instruction produced less initiation or expansion of social contact with peers, but they responded more to interactions (non-verbal and verbal) with peers than children without DT instruction. |

| UCLA/Lovaas | |||||

| Hilton JC, 2005[53a] USA | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 59 mo Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 5 | DIR N = 5 | 1) There were no significant differences between ABA and DIR intervention programs on measures of communication and symbolic behaviour. |

| Hilton JC, 2005[53b] USA | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 65.5 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Lovaas N = 5 | DIR N = 5 | 1) Children receiving ABA demonstrated significant improvement for language comprehension than DIR. 2) There were no significant differences between ABA and DIR intervention programs on measures of communication and symbolic behaviour. |

| Sallows GO, 2005[66] USA | RCT Parallel 4 yr | 33.6 mo Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 13 | Lovaas N = 10 | 1) The UCLA early intensive behavioural treatment can be implemented in a clinical setting. 2) Outcomes after 4 years of treatment (cognitive, language, adaptive, social, and academic measures), were similar for both groups. |

| Smith T, 2000[71] USA | RCT Parallel 7 yr | 35.9 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Lovaas N = 15 | Lovaas N = 13 | 1) The intensive treatment group was significantly superior to the parents training group at producing improvements in IQ, visual-spacial skills and language development. |

| Cohen H, 2006[88] USA | CCT Parallel 3 yr | 31.7 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Lovaas N = 21 | SE N = 21 | 1) There were no significant differences between the UCLA model implemented in a community setting and special education classes at local public schools in language comprehension and non-verbal skills. 2) EIBT can be successfully implemented in a community setting. |

| Eikeseth S, 2002[90], [166] Norway | CCT Parallel 12 mo | 65.7 mo Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 13 | SE N = 12 | 1) Children in the behavioural group displayed significantly fewer disruptive behaviours than the eclectic group. 2) The behavioural group showed more gains than the eclectic group on IQ, language and adaptive behaviour. |

| Howard JS, 2005[94] USA | CCT Parallel ∼14 mo | 33.6 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Lovaas N = 29 | SE N = 16 | 1) Learning rates at followup were substantially higher for children in the IBT group. 2) The IBT group had statistically higher mean standard scores in all skill domains than the control groups, except for motor skills. |

| Lovaas OI, 1987[99], [167] USA | CCT Parallel 30 mo | Age NR Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 19 | Lovaas N = 19 | 1) Participants in the intensive-long-term behaviour modification group obtained normal-range IQ scores and successful first grade performance in public schools. |

| Arnold CL, 2003[120] USA | RCS 9 yr | 40.8 mo Autistic disorder, PDD, Dual diagnosis of MR | Lovaas N = 17 | SE N = 16 | 1) Children in the ABA group did not make significant gain in cognitive ability but there was a trend of ABA improving and SE declining cognitive ability. 2) There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in intelligence measures, symptom severity and cognitive skills. |

| Eldevik S, 2006[122] Norway | RCS 2 yr | Age NR Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 13 | SC N = 15 | 1) Low-intensity behavioural treatment produced significant improvements in intellectual functioning, language comprehension, expressive language and communication skills when compared to an eclectic treatment group. |

| Farrell P, 2005[123] UK | RCS 2 yr | 44.5 mo Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 7 | DT+TEACCH N = 7 | 1) Both ABA/Lovaas and LUFAP parents and staff were satisfied with the programs. 2) Both groups of children made considerable progress on socialization, daily living skills, communication and intelligence measures. |

| Hutchison-Harris J, 2004[125] USA | RCS 3 yr | 39.1 mo Autistic disorder | Lovaas N = 44 | Lovaas N = 35 | 1) Three years of intensive ABA intervention produced statistically significant improvements in language, cognitive ability, adaptive behaviour and overall pathology. |

| Sheinkopf SJ, 1998[127] USA | RCS 20 mo | 34.6 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Lovaas N = 9 | RI N = 9 | 1) Participants in the home-based behavioural treatment obtained statistically significant higher IQ score at followup than the control. 2) There was a statistically significant reduction of symptoms severity after participating in the home-based behavioural treatment. |

| Smith T, 1997[128] USA | RCS ∼2–3 yr | 37.0 mo PDD | Lovaas N = 11 | Lovaas N = 10 | 1) Participants in the intensive behavioural treatment achieved higher IQ and had more expressive speech than the control. 2) Behavioural problems were reduced in both groups. 3) Intensively treated children achieved clinically meaningful gains relative to the comparison group but remained quite delayed. |

| COMMUNICATION-FOCUSED INTERVENTIONS | |||||

| Computer-Assisted Instruction | |||||

| Bolte S, 2006[38] Germany | RCT Parallel 5 wk | 27.3 mo Autistic disorder | Computer-assisted instruction N = 3 | NT N = 4 | 1) Facial affect recognition training did not produce a significant activation in the fusiform gyrus. 2) Facial affect recognition training produced some behavioural improvements. |

| Golan O, 2006[49a] UK | RCT Parallel 10–15 wk | 30.7 mo Asperger's syndrome, High-functioning autism | Computer-assisted instruction N = 19 | NT N = 22 | 1) Interactive multimedia produced improvement in emotion recognition and close, but not distant, generalization tasks. 2) No difference was found between the treatment groups on either feature- based or holistic tasks of distant generalization. |

| Golan O, 2006[49b] UK | RCT Parallel 10 wk | 24.95 mo Asperger's syndrome, High-functioning autism | Computer-assisted instruction N = 13 | Social skills program N = 13 | 1) Interactive multimedia significantly improved close generalization tasks. 2) The interactive multimedia intervention produced significant effects on verbal IQ. |

| Moore M, 2000[60] USA | RCT Parallel NR | Age NR Autistic disorder | Computer-assisted instruction N = NR | Computer-assisted instruction N = NR | 1) Children in the computer group were significantly more attentive, more motivated and learned more vocabulary than those in the behavioural program. |

| Silver M, 2001[69] UK | RCT Parallel NR | 172.2 mo Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome | Computer-assisted instruction N = 10 | RI N = 11 | 1) The computer program group was significantly superior to the control group on improving childrens' ability to recognize and predict emotions in others. |

| Williams C, 2002[80] UK | RCT Cross-over 10 wk | 56 mo Autistic disorder | Computer-assisted instruction N = 4 | RI N = 4 | 1) The study was not long enough to show substantial improvement in reading skills. 2) Children spoke >2 times the number of words during the computer than book condition. |

| Picture Exchange Communication System | |||||

| Carr D, 2007[87], [133] UK | CCT Parallel 5 wk | 68.0 mo Autistic disorder | PECS N = 24 | RI N = 17 | 1) PECS produced a significant increase in communication initiations and dyadic interactions compared to the control. |

| Sign Language Training | |||||

| Saraydarian KA, 1994[67] USA | RCT Parallel 1 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder | Sign language training N = 10 | NT N = 10 | 1) A controlled language training program produced an improvement in oral language and non-verbal communication in children with autism. |

| Yoder PJ, 1988[82], [168] USA | RCT Parallel NR | 64.2 mo Autistic disorder | Sign language training N = 15 | SLT N = 15 | 1) Speech alone, simultaneous presentation and alternating presentation conditions facilitated more child-initiated speech during treatment than the sign alone condition. |

| Sign language training+LT-simultaneous N = 15 | |||||

| Sign language training+LT-alternation N = 15 | |||||

| Oxman J, 1979[104] Canada | CCT Parallel 7 mo | 111 mo Autistic disorder, Autistic-like | Sign language training N = 5 | SLT N = 5 | 1) Simultaneous communication training produced some increase in the frequency of immediate vocal responding to speech models. |

| CONTEMPORARY ABA | |||||

| Cognitive Behavioural Therapy | |||||

| Berg HP, 2002[36] USA | RCT Parallel NR | 98.5 mo Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, PDD | CBT N = 10 | Control (ND) N = 9 | 1) Training in cognitive perspecive-taking may remediate deficits in language and visual perspective-taking ability. |

| Sofronoff K, 2007[72] Australia | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 129.4 mo Asperger’s syndrome | CBT N = 24 | WL N = 21 | 1) The cognitive behavioural intervention produced a significant decrease in episodes of anger and an increase in parents’ confidence in managing their child’s anger. |

| Sofronoff K, 2005[73] Australia | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 127.4 mo Asperger's syndrome | CBT N = 23 | CBT N = 25 | 1) The two intervention groups demonstrated significant decreases in parent-reported anxiety symptoms at followup and a significant increase in the child’s ability to generate positive strategies in an anxiety-provoking situation. |

| WL N = 23 | |||||

| Sofronoff K, 2002[74], [169] Australia | RCT Parallel 4 wk | 99 mo Asperger’s syndrome | CBT N = 32 | CBT N = 36 | 1) Both parent management training interventions produced significant improvement in the number and intensity of problem behaviours and ratings of social skills. 2) There was significant effect in self-efficacy between the groups. |

| WL N = 20 | |||||

| Tonge B, 2006[77] Australia | RCT Parallel 20 wk | 46.7 mo Autistic disorder | CBT N = 35 | CBT N = 33 | 1) Both parent education & behaviour management intervention and the parent education & counseling interventions resulted in significant improvement in overall mental health. 2) Parent education & behaviour management alleviated a greater percentage of anxiety, insomnia and somatic symptoms than parent education & counselling. |

| SC N = 35 | |||||

| Discrete Trial Training (contemporary) | |||||

| Jocelyn LJ, 1998[55] Canada | RCT Parallel 12 wk | 43.3 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | DT+IT N = 16 | SC N = 19 | 1) The caregiver-based intervention program produced greater gains in language abilities, significant increases in caregivers' kwledge of autism, greater perception of control on the mothers' part and greater parent satisfaction. 2) Significant difference in autism symptoms was found between the groups. |

| Kasari C, 2006[57] USA | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 42.6 mo Autistic disorder | DT+IT+PRT+Millieu Teaching N = 20 | DT+IT+PRT+Millieu Teaching N = 21 | 1) The joint attention group showed a significant increase in initiation and responsiveness to joint attention and improvements in mother-child interactions. 2) Children in the play group showed more diverse types of symbolic play and higher play levels in interaction with their mothers. 3) There were differences between joint attention and play groups on initiating shows and coordinating joint looks. |

| Control (ND) N = 17 | |||||

| Wang P, 2005[78] China | RCT Parallel 5 wk | 68.2 mo Autistic disorder | DT+IT N = 15 | WL N = 12 | 1) Parents in the training group performed significantly better on a measure of kwledge of autism. 2) Parents in the training group scored significantly higher on responsiveness during free play interactions. 3) There were differences between the groups in parental stress levels. |

| Incidental Teaching | |||||

| Bloch J, 1980[121] USA | RCS 24 mo | 47.7 mo Autistic disorder | IT N = 12 | RI N = 14 | 1) An individualized language development program produced significant gains in language development after 1 year of treatment. 2) The program facilitated the gain of prelinguistic and linguistic skills. |

| Pivotal Response Training | |||||

| Koegel RL, 1996[58] USA | RCT Parallel NR | 62.4 mo Autistic disorder | PRT N = 10 | PRT N = 7 | 1) Families in the PRT condition showed more positive interactions and better communication style when compared with the ITB intervention. 2) The ITB training condition did not appear to have any significant impact on the parents' interactional style. |

| Openden DA, 2005[63] USA | RCT Parallel 4 days | 61.0 mo Autistic disorder | PRT+DT N = 16 | WL N = 16 | 1) PRT significantly increased the expression of positive affect, responsivity to opportunities for language and functional verbal utterances. |

| Stahmer AC, 2001[113] USA | CCT Parallel 12 wk | 35.3 mo Autistic disorder | PRT N = 11 | PRT N = 11 | 1) The addition of a parent education support group to a parent education program may increase parent mastery of teaching techniques and children's language skills. |

| DEVELOPMENTAL APPROACHES | |||||

| Developmental Individual-difference Relationship-based Interventions | |||||

| Gonzalez JS, 2006[134], [170] USA | RCT Parallel 8 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder | DIR N = 4 | NT N = 4 | 1) Implementation of the DIR program did not produce significant changes in behavioural repetitive stereotypies when compared to a non-DIR program group. 2) There were significant changes in positive social interactions or negative social interaction skills between the groups. |

| Imitative Interaction | |||||

| Escalona A, 2002[45] USA | RCT Parallel NR | 62.6 mo Autistic disorder | Imitative interaction N = 10 | DCI N = 10 | 1) The contingency condition seemed to be more effective in facilitating a distal social behaviour (attention), while the imitative condition was more effective in facilitating a proximal social behaviour (touching). |

| Field T, 2001[48] USA | RCT Parallel NR | 64.8 mo Autistic disorder | Imitative interaction N = NR | DCI N = NR | 1) Repeated sessions of adult imitation increased both distal and proximal social behaviours. 2) Compared to contingently responsive group, imitation group showed significantly less time being inactive/playing alone and more time showing object behaviours. |

| Heimann M, 2006[52] Norway | RCT Parallel NR | 77.2 mo Autistic disorder | Imitative interaction N = 10 | DCI N = 10 | 1) An imitation interaction strategy produced a significant increase of both proximal and distal social behaviours compared to the contingency group. 2) The imitation intervention significantly increased children’s imitation skills at a more generalized level. |

| Incidental Teaching | |||||

| Eagle R, 2006[89] USA | CCT Cross-over NR | 88.7 mo Autistic disorder, Atypical autism, PDD | IT N = 12 | DIT N = 10 | 1) There were significant differences between the passive and social behaviour conditions on interpersonal distance and social initiation. |

| Milieu Therapy | |||||

| Yoder P, 2006[81], [171] USA | RCT Parallel 6 mo | 33.6 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Milieu therapy N = 17 | PECS N = 19 | 1) PECS was more successful than RPMT in increasing the frequency of different non-imitative spoken communication acts and the number of different non-imitative words. |

| Macalpine ML, 1999[101] USA | CCT Parallel 8 mo | Age NR Autistic disorder | Milieu therapy N = 12 | NT N = 6 | 1) The microdevelopmental method facilitated the development of higher cognitive abilities and successfully reversed the course of autism. |

| Wetherby AM, 2006[119] USA | PCS NR | 25.1 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Milieu therapy N = 17 | Milieu therapy N = 18 | 1) This program produced significant improvements in communication measures compared to the control. 2) There were differences between the groups on communicative means and play behaviour. |

| More Than Words | |||||

| McConachie H, 2005[103] UK | CCT Parallel 7 mo | 36.6 mo Autistic disorder, PDD, Not yet diagnosed autism | More than Words N = 26 | WL N = 25 | 1) The More than Words program produced a significant advantage in parents' observed use of facilitative strategies and in childrens' vocabulary size. 2) There were significant differences between the groups on children's social score or behaviour, parental stress or adaptation. |

| Responsive Training | |||||

| Aldred C, 2004[32] UK | RCT Parallel 12 mo | 49.5 mo Autistic disorder | Responsive Training N = 14 | SC N = 14 | 1) A dyadic social communication treatment can improve autistic symptoms across severity and age groups in terms of quality of reciprocal social communication and expressive language. |

| Beckloff DR, 1997[84] USA | CCT Parallel 10 wk | 75.6 mo Autistic disorder, Atypical autism, PDD, High-functioning autism | Responsive Training N = 12 | NT N = 11 | 1) Filial therapy produced a non-significant but positive trend in parents' attitude toward autism, children's aggressive problems, externalizing problems and depressive or anxiety symptoms. |

| Scottish Centre program | |||||

| Salt J, 2002[111] Scotland | CCT Parallel 10 mo | 41.0 mo Autistic disorder | Scottish Centre N = 12 | WL N = 5 | 1) A developmentally-based early intervention program produced improvements on measures of joiunt attention, social interaction, imitation, daily living skills, motor skills and adaptive behaviour. |

| ENVIRONMENTAL MODIFICATION | |||||

| Work Placement | |||||

| Garcia-Villamisar D, 2007[116] Spain | PCS 30 mo | Age NR Autistic disorder | Work placement N = NR | WL N = NR | 1) Supported employment produced a significantly greater improvement in non-vocational outcomes. 2) The intervention elicited positive changes in cognitive performance. |

| INTEGRATIVE PROGRAMS | |||||

| Discrete Trial Training (DT) combinations | |||||

| Drew A, 2002[40] UK | RCT Parallel 12 mo | 22.5 mo Autistic disorder | DT+PRT+Millieu Teaching N = 12 | SC N = 12 | 1) There was some evidence that the parent training group made more progress in language development. 2) The language ability of both groups remained severely compromised at followup. 3) Groups did t differ in non-verbal IQ, symptom severity or parental stress at followup. |

| Jelveh M, 2003[97] USA | CCT Parallel 5 mo | 58.5 mo Autistic disorder | DT+Floor time N = 9 | WL N = 5 | 1) Treatment groups showed improvements in social play and increased social behaviours. |

| Shade-Monuteaux DM, 2003[112] USA | CCT Cross-over 3 mo | 25.2 mo Autistic disorder | DT+Floor time N = 23 | NT N = 22 | 1) An integrated treatment approach is effective in improving social communication and joint attention skills in young children with ASD. |

| Lego Therapy | |||||

| Legoff DB, 2006[126] USA | RCS 3 yr | 112.8 mo Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, PDD | Lego Therapy N = 60 | SC N = 57 | 1) Lego therapy produced significant gains on measures of social skills and autistic symptoms compared to the control group. |

| Social skills program | |||||

| Kalyva E, 2005[56] UK | RCT Parallel 2 mo | 49.6 mo Autistic disorder | Social skills program N = 3 | WL N = 2 | 1) Circle of friends can improve the communication and social skills of children with autism. |

| Lanquetot R, 1989[59] USA | RCT Parallel 4 wk | 61.2 mo Autistic disorder | Social skills program N = 10 | RI N = 10 | 1) Peer modeling produced a significant decrease in autistic, angry and aggressive behaviours in the treatment group. |

| Solomon M, 2004[75] USA | RCT Parallel 20 wk | 112.4 mo Asperger’s syndrome, PDD, High-functioning autism | Social skills program N = 9 | WL N = 9 | 1) The social adjustment group showed statistically significant improvements in facial expression recognition and problem solving. |

| Lopata C, 2006[98] USA | CCT Parallel 6 wk | 120 mo Aperger's syndrome | Social skills program N = 9 | Social skills program N = 12 | 1) There were significant differences between treatment and control groups in parent-rated and staff-rated social skills, adaptability and atypical behaviour. |

| Ozonoff S, 1995[106] USA | CCT Parallel 4.5 mo | 164.5 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | Social skills program N = 5 | NT N = 4 | 1) A social skills training program produced non-significant but considerable improvements on false belief tasks. 2) The intervention did not produce changes in parent and teacher ratings of social competence. |

| Provencal SL, 2003[108] USA | CCT Parallel 8 mo | 171.6 mo Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome | Social skills program N = 10 | SC N = 9 | 1) Participants receiving the social skills intervention did not demonstrate statistically significant improvements in social and behavioural functioning at home or school. 2) Marginal effectiveness reported for some symptoms. |

| Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children (TEACCH) | |||||

| Ozonoff S, 1998[105] USA | CCT Parallel 4 mo | 53.4 mo Autistic disorder | TEACCH N = 11 | SC N = 11 | 1) A home program intervention improved significantly more in imitation, fine motor, gross motor, non-verbal conceptual skills and overall PEP-R scores. 2) The home program intervention was effective in enhancing development in young children with autism. |

| Panerai S, 2002[107] Italy | CCT Parallel 12 mo | 111.1 mo Autistic disorder | TEACCH N = 8 | RI N = 8 | 1) TEACCH program was more effective than the control 2) TEACCH produced significant changes in cognitive performance, developmental age, motor skills, daily living skills, play and leisure. |

| Tsang SKM, 2007[114] China | CCT Parallel 6 mo | 48.7 mo Autistic disorder, PDD | TEACCH N = 18 | SC N = 16 | 1) The TEACCH program produced a significantly greater improvement in measures of perception, fine motor, gross motor skills, social adaptive functioning and developmental abilities than the control. |

| Van Bourgondien ME, 2003[115] USA | CCT Parallel 6 mo | 25.6 mo Autistic disorder | TEACCH N = 6 | Family homes N = 8 | 1) Participants in the TEACCH program experienced a higher quality of treatment as compared to participant in control settings. 2) TEACCH participants had a significant increase in communication, socialization, developmental planning and positive behaviour management. |

| Group homes N = 11 | |||||

| Institutions N = 5 | |||||

| SENSORY MOTOR INTERVENTIONS | |||||

| Auditory Integration Training | |||||

| Bettison S, 1996[37] Australia | RCT Parallel 1 mo | Range = 3–17 yr Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome | AIT N = 40 | Unmodified music N = 40 | 1) The AIT and control groups showed similar improvement in behaviour, severity of autism and verbal and performance IQ. 2) Both AIT and listening to unmodified music may have a beneficial effect on children with autism. |

| Edelson SM, 1999[42] USA | RCT Parallel 3 mo | 139.0 mo Autistic disorder | AIT N = 9 | Unmodified music N = 9 | 1) AIT showed significant improvements in auditory P300 ERP and behavioural problems. |

| Mudford OC, 2000[61] UK | RCT Cross-over 3 mo | 113 mo Autistic disorder | AIT N = 7 | Unmodified music N = 9 | 1) The control condition was superior than AIT on parent-rated hyperactivity and direct observation measures of ear-occlusion. 2) There were differences in intelligence measures and language comprehension between groups at followup. |

| Rimland B, 1995[65] USA | RCT Parallel 3 mo | 123 mo Autistic disorder | AIT N = 9 | Unmodified music N = 9 | 1) AIT produced statistically significant improvements in adaptive behaviour. 2) AIT did not decrease sound sensitivity in children with autism. |

| Smith DE, 1985[70] USA | RCT Parallel 20 wk | 106 mo Autistic disorder | AIT N = 7 | NT N = 7 | 1) AIT produced an increase in attentiveness, appropriate behaviour, communication, signing and less stereotypies. |

| Exercise | |||||

| Greer-Paglia K, 2006[92] USA | CCT Cross-over 30 wk | 89.2 mo Autistic disorder | Exercise N = 29 | Social stories N = 25 | 1) Creative dance produced significantly greater social gains than in circle time condition for both verbal and non-verbal children. 2) The performance gap between verbal and non-verbal autistic children was smaller in the creative dance group than circle time group. |

| Mason MA, 2005[102] USA | CCT Parallel 10 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, PDD, Autistic savant | Exercise N = 56 | SC N = 33 | 1) Therapeutic horse riding produced a significant increase in communication and social skills. |

| Restricted Environmental Stimulation Therapy | |||||

| Harrison JR, 1991[51] USA | RCT Parallel 8 wk | 149.2 mo Autistic disorder | REST N = 6 | Ward placement N = 6 | 1) There were significant differences between REST and the control group in measures of stress, intelligence, vocal behaviour and autistic symptoms. |

| Suedfeld P, 1983[76] Canada | RCT Cross-over 6 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder | REST N = 5 | Ward placement N = 3 | 1) REST produced statistical significant positive changes in learning, social and play behaviour and cognitive functioning. |

| Sensory Integration | |||||

| Edelson SM, 1999[43] USA | RCT Parallel 6 wk | 91.0 mo Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 5 | Placebo N = 7 | 1) There was a significant reduction in tension and a marginally significant reduction in anxiety for children who received deep pressure compared to children who did not. 2) Deep pressure may have a calming effect for persons with autism, particularly those with high levels of arousal or anxiety. |

| Escalona A, 2001[44] USA | RCT Parallel 1 mo | 62.5 mo Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 10 | Reading N = 10 | 1) Massage therapy provided by parents appears to be an effective way of diminishing sleep problems, stereotypies and off-task behaviour. |

| Field T, 1997[47] USA | RCT Parallel 4 wk | 54 mo Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 11 | Unstructured play N = 11 | 1) Both the touch therapy and the touch control groups improved in measures of touch aversion and off-task behaviour. 2) The touch therapy group significantly decreased stereotypic behaviours compared to the touch control group. |

| Jarusiewicz B, 2002[54] USA | RCT Parallel 6–8 mo | 84 mo Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 12 | WL N = 12 | 1) Neuro-feeback training produced significant improvements in autism symptoms and behaviour. |

| Luce JB, 2003[100] USA | CCT Parallel 6 mo | 68 mo Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 12 | NT N = 12 | 1) There was difference between groups in the proportion of time children were enganged in stereotypic behaviours. |

| Hartshorn K, 2001[117] USA | PCS 2 mo | Age NR Autistic disorder | Sensory integration N = 38 | Control (ND) N = 38 | 1) Movement therapy led to a significant increase in attentive behaviours and a decrease in stress behaviours and touch aversion. |

| SOCIAL SKILLS DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS | |||||

| Social Stories | |||||

| Andrews SM, 2005[34] USA | RCT Parallel 1 day | 120.6 mo Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 10 | Regular story N = 10 | 1) The social story was effective in increasing game playing skills, story comprehension and generalized social comprehension. |

| Bader R, 2006[35] USA | RCT Cross-over 3 days | 105.2 mo Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 10 | Regular story N = 10 | 1) Social stories succesfully increased facial emotion learning and labeling for children with autism. |

| Feinberg MJ, 2002[46] USA | RCT Parallel 1 wk | 122.5 mo Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 17 | Regular story N = 17 | 1) Social stories is an effective intervention to teach social skills to children with autism. |

| Quirmbach LM, 2006[64] USA | RCT Parallel 1 wk | 114.7 mo Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 15 | Social Stories N = 15 | 1) Social stories using either a standard or a directive approach produced significantly higher game play skills than the control group. 2) Standard and directive groups did t significantly differ on rate of play skill improvement. |

| Control (ND) | |||||

| Ricciardelli D, 2006[109] USA | CCT Parallel 10 mo | 134.0 mo Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 3 | RI N = 3 | 1) Social stories combined with social skills curriculum did not produce significantly different changes in measures of social skills. 2) There was a significant difference in maintaining attention, favouring the treatment group. |

| Romano J, 2002[110,110] USA | CCT Parallel 6 wk | Age NR Autistic disorder | Social Stories N = 5 | NT N = 5 | 1) Social stories significantly decreased aggressive behaviour and improved communication and socialization skills. |

ABA = applied behaviour analysis; AIT = auditory integration training; ASD = autism spectrum disorders; CBT = cognitive behaviour therapy; CCT = controlled clinical trial; CFI = communication-focused intervention; DCI = developmental contingency interaction; DIT = developmental incidental teaching; DIR = developmental individual-difference relationship-based intervention; DT = discrete trial training; EM = environmental modification; ERP = event-related potential; IBT = intensive behaviour analytic treatment; IQ = Intellectual quotient; IT = incidental teaching; LEAP = learning experiences, an alternative program for preschoolers and their parents; LT = language therapy; LUFAP = Lancashire under fives autism programme; M = number of males; mo = month(s); MR = mental retardation; ND = not described; NR = not reported; NT = no treatment; OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder; PCS = prospective cohort study; PDD = pervasive developmental disorder; PECS = picture exchange communication system; PRT = pivotal response training; RCS = retrospective cohort study; RCT = randomized controlled trial; REST = restricted environmental stimulation therapy; RI = regular instruction; RPMT = responsive education and prelinguistic milieu teaching; SC = standard care; SE = special education ; SLT = speech language therapy; TEACCH = treatment and education of autistic and related communication-handicapped children; UCLA = University of California, Los Angeles wk = week(s); WL = wait-list; yr = year(s).

Quality of Studies

Details on the methodological quality of the studies are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Briefly, the majority of trials (83 percent) failed to mention how representative the sample was in terms of the study setting, the selection criteria for enrolling participants, and the operational definition of ASD. A minority of studies (32 percent) reported on monitoring the fidelity of intervention implementation. Although more than half of the trials (64 percent) reported the use of randomization, few trials (seven trials) reported the procedure for separating the process of randomization from the recruitment of participants. The majority of trials (89 percent) failed to clearly report how they concealed the sequence of allocation to the interventions under study. Less than half of the studies (43 percent) reported that blind or independent outcome assessment was conducted. In terms of attrition bias, 33 percent of the trials provided a description of withdrawals and dropouts from the study. Finally, just over half of the trials (54 percent) reported their sources of funding. Thirty-two percent were funded by government agencies, 22 percent received funding from foundations or societies, 19 percent used internal funds, and five percent were funded by private industry.

Table 2. Methodological quality of RCTs and CCTs.

| Study | Intervention | QUALITY DOMAINS | ||||||

| Method for sequence generation | Description of selection criteria | Description of therapeutic regimen | Blinding of outcome assessment | ITT analysis | Prior estimate of sample size | Funding reported | ||

| Allocation concealment | Withdrawals per group reported | Description of treatment provider | Assessment of treatment fidelity | Testing randomization | Report of measures of precision | |||

| Andrews E, 1998[33] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Collier D, 1987[39] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Yes | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Dugan KT, 2006[41] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Harris SL, 1982[50] RCT | ABA/DT | Inappropriate | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Nelson DL, 1980[62] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Partial | |||

| Sherman J, 1988[68] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| White SJ, 2000[79] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Yes | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Zifferblatt SM, 1977[83] RCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Bernard-Opitz V, 2004[85] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Yes | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Birnbrauer JS, 1993[86] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Elliott RO Jr, 1991[91] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Yes | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Harris SL, 1990[93] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Howlin P, 1981[95] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | NA | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Hung DW, 1983[96] CCT | ABA/DT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Yes | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Hilton JC, 2005[53a] RCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Yes | Partial | Partial | |||

| Hilton JC, 2005[53b] RCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Yes | Partial | Partial | |||

| Sallows GO, 2005[66] RCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | No | Adequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Smith T, 2000[71] RCT | ABA/Lovaas | Appropriate | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | No | Adequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Cohen H, 2006[88] CCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Yes | Adequate | Adequate | |||

| Eikeseth S, 2002[90] CCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | |||

| Howard JS, 2005[94] CCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | No | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Lovaas OI, 1987[99] CCT | ABA/Lovaas | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Bolte S, 2006[38] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Golan O, 2006[49a] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Golan O, 2006 [49b] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Moore M, 2000[60] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Silver M, 2001[69] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Williams C, 2002[80] RCT | Communication focused/Computer-assisted instruction | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Carr D, 2007[87] CCT | Communication focused/PECS | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Saraydarian KA, 1994[67] RCT | Communication focused/Sign language training | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Yoder PJ, 1988[82] RCT | Communication focused/Sign language training | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Oxman J, 1979[104] CCT | Communication focused/Sign language training | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Berg HP, 2002[36] RCT | Contemporary ABA/CBT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Sofronoff K, 2007[72] RCT | Contemporary ABA/CBT | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Sofronoff K, 200573 RCT | Contemporary ABA/CBT | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Sofronoff K, 2002[74] RCT | Contemporary ABA/CBT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | Yes | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Tonge B, 2006[77] RCT | Contemporary ABA/CBT | Appropriate | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Jocelyn LJ, 1998[55] RCT | Contemporary ABA/DT+IT | Appropriate | Adequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | Yes | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Kasari C, 2006[57] RCT | Contemporary ABA/DT+IT+PRT+Millieu Teaching | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Wang P, 2005[78] RCT | Contemporary ABA/DT+IT | Unclear | Partial | Partial | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Koegel RL, 1996[58] RCT | Contemporary ABA/PRT | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | NA | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Openden DA, 2005[63] RCT | Contemporary ABA/PRT+DT | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Stahmer AC, 2001[113] CCT | Contemporary ABA/PRT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes | Partial | Partial | |||

| Gonzalez JS, 2006[134] RCT | Developmental/DIR | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Escalona A, 2002[45] RCT | Developmental/Imitative interaction | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Field T, 2001[48] RCT | Developmental/Imitative interaction | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Heimann M, 2006[52] RCT | Developmental/Imitative interaction | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Partial | Partial | |||

| Eagle R, 2006[89] CCT | Developmental/Incidental Teaching | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Yoder P, 2006[81] RCT | Developmental/Milieu therapy | Appropriate | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Macalpine ML, 1999[101] CCT | Developmental/Milieu therapy | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| McConachie H, 2005[103] CCT | Developmental/More than Words | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes | Adequate | Adequate | |||

| Aldred C, 2004[32] RCT | Developmental/Resposive Training | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | Yes | Yes | Inadequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | Yes | NA | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Beckloff DR, 1997[84] CCT | Developmental/Resposive Training | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Adequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Salt J, 2002[111] CCT | Developmental/Scottish Centre | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Drew A, 2002[40] RCT | Integrative Programs/DT+PVT+Millieu Teaching | Appropriate | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Jelveh M, 2003[97] CCT | Integrative Programs/DT+Floor time | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Shade-Monuteaux DM, 2003[112] CCT | Integrative Programs/DT+Floor time | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Inappropriate | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Kalyva E, 2005[56] RCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Partial | |||

| Lanquetot R, 1989[59] RCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Appropriate | Partial | Inadequate | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Appropriate | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Partial | Inadequate | |||

| Solomon M, 2004[75] RCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Lopata C, 2006[98] CCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Inappropriate | Inadequate | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Ozonoff S, 1995[106] CCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Provencal SL, 2003[108] CCT | Integrative Programs/Social skills program | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Partial | Yes | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Ozonoff S, 1998[105] CCT | Integrative Programs/TEACCH | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Panerai S, 2002[107] CCT | Integrative Programs/TEACCH | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Tsang SKM, 2007[114] CCT | Integrative Programs/TEACCH | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Van Bourgondien ME, 2003[115] CCT | Integrative Programs/TEACCH | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Bettison S, 1996[37] RCT | Sensory Motor/AIT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Adequate | Yes |

| Appropriate | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Edelson SM, 1999[42] RCT | Sensory Motor/AIT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Mudford OC, 2000[61] RCT | Sensory Motor/AIT | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Rimland B, 1995[65] RCT | Sensory Motor/AIT | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Smith DE, 1985[70] RCT | Sensory Motor/AIT | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Yes | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Greer-Paglia K, 2006[92] CCT | Sensory Motor/Exercise | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Adequate | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Mason MA, 2005[102] CCT | Sensory Motor/Exercise | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Harrison JR, 1991[51] RCT | Sensory Motor/Rest | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Suedfeld P, 1983[76] RCT | Sensory Motor/Rest | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | NA | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Edelson SM, 1999[43] RCT | Sensory Motor/SI | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | No | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Escalona A, 2001[44] RCT | Sensory Motor/SI | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Field T, 1997[47] RCT | Sensory Motor/SI | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | Yes |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Inadequate | |||

| Jarusiewicz B, 2002[54] RCT | Sensory Motor/SI | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | Yes | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Luce JB, 2003[100] CCT | Sensory Motor/SI | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

| Andrews SM, 2005[34] RCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Appropriate | Inadequate | Partial | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Yes | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Bader R, 2006[35] RCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Partial | Partial | |||

| Feinberg MJ, 2002[46] RCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Unclear | Partial | Partial | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Inadequate | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Quirmbach LM, 2006[64] RCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Inappropriate | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Inappropriate | No | Partial | Unclear | Adequate | Partial | |||

| Ricciardelli D, 2006[109] CCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Unclear | Inadequate | Adequate | Unclear | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Partial | |||

| Romano J, 2002[110] CCT | Social skills development/Social Stories | Unclear | Partial | Adequate | No | No | Inadequate | No |

| Unclear | No | Partial | Unclear | Inadequate | Partial | |||

ABA = applied behavioural analysis; AIT = auditory integration training; DT = discrete trial; IT = incidental teaching; NA = not applicable; ND = not described; PCS = prospective cohort study; PECS = picture exchange communication system; RCS = retrospective cohort study; SI = sensory integration.

Table 3. Methodological quality of observational studies.

| Study | Intervention Type | QUALITY DOMAINS | Funding | ||||

| Report of selection criteria | Report of therapeutic regimen | Measure of exposure assessment reliable | Main potential confounders incorporated in design/analysis | Report of measures of precision | |||

| Representa-tiveness of exposed cohort | Report of treatment provider | Outcome assessment blind to exposure status | Important differences between groups other than exposure to intervention | Report of how potential confounders were distributed | |||

| Method of outcome assessment valid and reliable | |||||||

| Pechous EA, 2001[118] PCS | ABA/DT | Partial | Inadequate | Partial | Partial | Partial | No |

| Somewhat | Inadequate | ND | No | No | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Fenske EC, 1985[124] RCS | ABA/DT | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | Partial | Inadequate | No |

| Somewhat | Inadequate | ND | Yes | Yes | |||

| ND | |||||||

| Tung R, 2005[129] RCS | ABA/DT | Partial | Partial | Partial | No | Inadequate | No |

| Yes | Inadequate | ND | No | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Arnold CL, 2003[120] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Partial | Partial | Partial | No | Partial | No |

| Somewhat | Partial | ND | Yes | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Eldevik S, 2006[122] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Partial | Yes |

| Somewhat | Adequate | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Farrell P, 2005[123] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Inadequate | Partial | ND | No | Inadequate | No |

| Somewhat | Partial | ND | Yes | No | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Hutchison-Harris J, 2004[125] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| Somewhat | Adequate | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Sheinkopf SJ, 1998[127] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Inadequate | Adequate | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| ND | Partial | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Smith T, 1997[128] RCS | ABA/Lovaas | Adequate | Adequate | Yes | Partial | Partial | No |

| ND | Adequate | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Bloch J, 1980[121] RCS | Contemporary ABA/IT | Inadequate | Inadequate | Yes | No | Inadequate | No |

| Somewhat | Partial | No | Yes | No | |||

| No | |||||||

| Wetherby AM, 2006[119] PCS | Developmental/Milieu therapy | Partial | Adequate | Yes | No | Partial | Yes |

| Yes | Adequate | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Garcia-Villamisar D, 2007[116] PCS | Environmental Modification/Work placement | Partial | Partial | ND | No | Partial | Yes |

| Yes | Inadequate | ND | No | Yes | |||

| ND | |||||||

| Legoff DB, 2006[126] PCS | Integrative Programs/Lego Therapy | Inadequate | Inadequate | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| Somewhat | Inadequate | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Yes | |||||||

| Hartshorn K, 2001[117] PCS | Sensory Motor/SI | Inadequate | Partial | ND | Yes | Partial | Yes |

| ND | Partial | Yes | No | No | |||

| Yes | |||||||

ABA = applied behavioural analysis; DT = discrete trial; IT = incidental teaching; ND = not described; PCS = prospective cohort study; RCS = retrospective cohort study; SI = sensory integration.

Overall, the methodological quality of the 14 cohort studies was modest. In general, the cohort studies failed to protect against selection bias: only three studies clearly mentioned how representative the overall sample was in terms of the study setting, the description of the selection criteria, and the operational definition of ASD used for the study. The control for detection bias affecting the ascertainment of both exposure and outcome was moderate in the cohort studies. None of the studies used secure methods for ascertainment of exposure. The majority of the studies provided evidence on the reliability of methods for outcome assessment; however, only half of the studies explicitly stated that outcome assessment was blind to exposure status. Finally, only four observational studies disclosed their source of funding. The methodological strengths and weaknesses of individual studies, presented in Table 2 and Table 3, should be taken into consideration when interpreting the study results and conclusions.

Summary of Findings

Applied Behaviour Analysis

Evidence from 31 studies (12 trials and 9 cohort studies) involving a total of 770 participants was analyzed on the use of discrete trial training and Lovaas therapy for ASD. The effects of discrete trial learning are inconsistent across studies. All the studies that compared discrete trial training to no treatment reported statistically significant findings [95], [118], [129]. Motor and functional outcomes more often demonstrated positive results compared to speech-related outcomes which were generally negative. All cohort studies demonstrated significant results [118], [124], [129]. Lovaas therapy was consistently found superior to standard care [99], [122] or regular instruction [94], [127] in terms of intellectual functioning, language comprehension, and communication skills. Generally, high-intensity Lovaas was found to be superior to low-intensity Lovaas in terms of intellectual functioning, communication skills, adaptive behaviour and overall pathology [71], [99], [125], [128]. The results for Lovaas therapy compared to special education showed variable results at the individual study level and seemed to indicate more effect for the medium-term (12 and 14 months, respectively) [90], [94] which was not apparent within the longer-term studies (3 and 9 years, respectively) [88], [120]. No significant differences were found within studies comparing Lovaas to Developmental Individual-difference relationship-based intervention (DIR) [53] or Integrative/Discrete trial combined with Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) [123]. Seven of the eight studies that reported significant findings for Lovaas therapy were non-RCTs [90], [94], [99], [122], [125], [127], [128]. Three of the four RCTs in this category reported no significant findings [53a,53b,66]. This observation has serious implications for the interpretation of evidence from non-RCTs. There is some evidence that results of RCTs and non-RCTs sometimes, but not always, differ,[130] and that non-RCT can be more prone to bias and overestimate treatment effects [131], [132].

Communication-focused Interventions

Ten trials involving 269 participants were identified that evaluated the effects of communication-focused interventions. Positive effects and statistically significant results were produced at the study level for emotional recognition [49], [69], close generalization tasks [49], verbal IQ [49], attention [60] and motivation [60]; these studies were all RCTs and had varied control groups including no treatment, as well as active interventions. There is evidence from three trials (2 RCT, 1 CCT) that sign language training provides benefits in terms of communication-related outcomes, such as articulation competence, oral language, nonverbal communication, and child-initiated speech [67], [82], [104]. There is also some suggestion that sign language training may be most effective when combined with other modalities [82]. One CCT of Picture Exchange Communication System versus regular instruction showed a significant increase in communication initiations and dyadic interactions [133].

Contemporary ABA