Abstract

GnRH neurons must undergo a complex and precise pattern of neuronal migration to appropriately target their projections to the median eminence to trigger gonadotropin secretion and thereby control reproduction. Using NLT GnRH cells as a model of early GnRH neuronal development, we identified the potential importance of Axl and Tyro3, members of the TAM (Tyro3, Axl, and Mer) family of receptor tyrosine kinases in GnRH neuronal cell survival and migration. Silencing studies evaluated the role of Tyro3 and Axl in NLT GnRH neuronal cells and suggest that both play a role in Gas6 stimulation of GnRH neuronal survival and migration. Analysis of mice null for both Axl and Tyro3 showed normal onset of vaginal opening but delayed first estrus and persistently abnormal estrous cyclicity compared with wild-type controls. Analysis of GnRH neuronal numbers and positioning in the adult revealed a total loss of 24% of the neuronal network that was more striking (34%) when considered within specific anatomical compartments, with the largest deficit surrounding the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. Analysis of GnRH neurons during embryogenesis identified a striking loss of immunoreactive cells within the context of the ventral forebrain compartment (36%) and not more rostrally. Studies using caspase 3 cleavage as a marker of apoptosis showed that Axl−/−, Tyro3−/− double-knockout mice had increased cell death in the nose and dorsal forebrain, supporting the underlying mechanism of cell loss. Together these data suggest that Axl and Tyro3 mediate the survival and appropriate targeting of GnRH neurons to the ventral forebrain, thereby contributing to normal reproductive function and cyclicity in the female.

GnRH NEURONS UNDERGO a precisely orchestrated pattern of neuronal migration from the olfactory placode area to the hypothalamus. GnRH is produced by a small number of neurons that originate in the nasal region and migrate during development to their ultimate destination in the forebrain (1,2). GnRH mRNA and peptide production begins in cells in or near the olfactory placode at embryonic d 10–11 (E10–11). The neurons migrate along the olfactory nerves to the cribriform plate (E12–17, mouse) and then diverge; the olfactory fibers continue on to the olfactory bulb, whereas the GnRH neurons turn caudally and ventrally and follow vomeronasal nerve fibers to their final destinations in the forebrain (3). The signals that control these precisely defined migratory routes may be myriad and vary depending upon precise location within the route (reviewed in in Refs. 4,5,6). Although the total number of GnRH neurons in the adult animal is small (800 in mice, several thousand in primates or humans), reports suggest that the population is larger during the early stages of the migratory process (in mice, approximately 1500 at E15) (7), suggesting the importance of survival and appropriate targeting of the neuronal population. Failure of appropriate GnRH neuronal migration results in failure of sexual maturation and GnRH deficiency syndromes in humans (2,8,9,10).

GnRH Neuronal Cell Lines as Models of GnRH Neuronal Development

Immortalized GnRH neuronal cell lines provide in vitro models of GnRH neuronal development. NLT cells were derived from a tumor in the mouse olfactory region after SV40 T antigen-targeted tumorigenesis and represent early GnRH neurons with low levels of GnRH peptide synthesis and an intrinsic migratory phenotype (11). GT1-7 GnRH cells were derived from a mouse forebrain tumor and represent a postmigratory GnRH neuron phenotype with high levels of GnRH mRNA and peptide (12). We initially identified the tyrosine kinase Axl (13,14) as up-regulated in NLT but not GT1-7 neurons (15) and have previously outlined its role in cell survival (16) and migratory signaling (17,18) and in the inhibition of GnRH gene expression (17,19) in GnRH neuronal cells.

TAM Family: Role in GnRH Neuronal Development?

Axl belongs to the TAM (Tyro3, Axl, and Mer) family of tyrosine kinases that are comprised of an extracellular domain with characteristics of neural cell adhesion molecules, containing fibronectin and Ig repeats as well as an intracellular kinase (14,20,21). Growth arrest specific gene 6 (Gas6) and in some tissues the closely related protein S (ProS1) are ligands for the TAM family members (22,23). The TAM family has been repeatedly identified as overexpressed in hematopoietic tumors (13,24,25), but these proteins are also normally expressed in a cell- and tissue-specific manner (21). Some tissues express all the family members, whereas others express selected receptors and/or their ligands (26,27). The mechanism of action (21,28) for the TAM family is complex due to of the ability of the receptors to form hetero- as well as homodimers and the ability of Gas6 and/or ProS1 to not only interact with and signal through the full-length receptor, but to also bind extracellular domain fragments to promote or antagonize signaling (21). Deletion of one or two members of the TAM family was reported to lack a reproductive phenotype, but deletion of all three family members resulted in spermatogenic deficits in males and undefined problems with fertility in females (29,30,31). Recent studies detected distal vaginal atresia in mice lacking Mer alone or in combination with Axl and/or Tyro3 but not in mice lacking Axl and/or Tyro3 with a normal complement of Mer (32). With aging, Tyro3-null mice develop cerebellar ataxia, and immune defects are observed with the progressive loss of the TAM family, especially those including Mer (21).

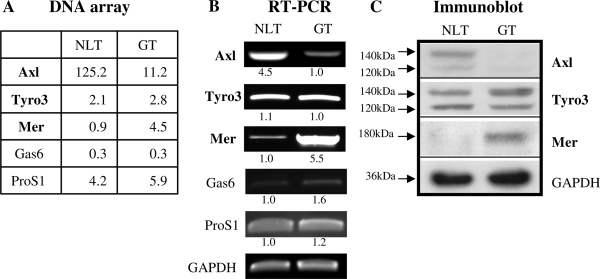

Evolving data suggest the importance of multiple TAM members in cell-specific effects; therefore, we analyzed the expression profile of Tyro3 and Mer in relation to Axl in the immortalized GnRH neuronal cell lines. Analysis of a DNA array showed that NLT cells as a model of early migratory GnRH neurons express both Tyro3 and Axl, but not Mer, whereas GT1-7 cells as a model of postmigratory GnRH neurons express Tyro3 and Mer and not Axl. Thus, we hypothesized that Axl may cross talk with Tyro3 to mediate migration and/or survival and impact on the ontogeny and capacity of the GnRH neuronal network during development. To further examine their functional role in vivo, we characterized the reproductive phenotype and GnRH neuronal ontogeny in mice null for Axl and Tyro3 and dissected the contribution of Tyro3 in addition to Axl in survival and migration of GnRH neuronal cells.

RESULTS

Tyro3, Axl, and Mer Are Differentially Expressed in GnRH Neuronal Cells

We performed DNA microarrays on triplicate samples of NLT and GT1-7 GnRH neuronal cell mRNA to assess the expression of TAM family members and their ligands Gas6 and ProS1. Data were normalized to the chip and the database queried for levels of transcripts for Axl, Tyro3, Mer, Gas6, and ProS1 (Fig. 1A). Axl was the most abundant of the TAM family transcripts. NLT GnRH neuronal cells expressed high levels of Axl transcript and low levels of Mer, whereas GT1-7 neuronal cells produced higher levels of Mer. Similar levels of Tyro3 and ProS1 and low levels of Gas6 transcript were observed in both cell lines. Semiquantitative RT-PCR using GAPDH as an internal control confirmed differential expression of the Axl family mRNAs in the GnRH cell lines (Fig. 1B). Levels of Axl mRNA were higher in NLT cells than GT1-7 cells, but the difference was more modest than in the array (6-fold vs. 10-fold). As expected, Mer mRNA was expressed at 5-fold higher levels in GT1-7 cells compared with NLT cells. Tyro3 mRNA levels were comparable in both cell lines. ProS1 mRNA levels were similar between the neuronal cells, and Gas6 mRNAs were quite low.

Figure 1.

Differential Expression of TAM Family Members in GnRH Neuronal Cells

A, Normalized transcript levels of Axl, Tyro3, Mer, Gas6, and ProS1 from triplicate DNA microarray analysis (see Materials and Methods for details). B, Semiquantitative RT-PCR of TAM family member mRNA levels in NLT and GT1-7 GnRH neuronal cells. Numbers refer to fold differences in TAM mRNA levels between NLT and GT1-7 cells. C, Immunoblot of TAM family member protein levels expressed in NLT and GT1-7 GnRH neuronal cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

To assess levels of the TAM proteins in GnRH neuronal cells, NLT and GT1-7 cell lysates were immunoblotted and probed with antibodies specific for each receptor protein (Fig. 1C). NLT migratory GnRH neuronal cells expressed Axl and Tyro3 protein, but not Mer. In contrast, GT1-7 postmigratory GnRH neuronal cells expressed Mer and Tyro3 protein but not Axl, despite the fact that low levels of Axl mRNA were present. Gas6 protein was not detected in either cell line (data not shown), consistent with a potential role for exogenous Gas6 from adjacent neurons or glia (27) to modulate TAM function in vivo. Based on the findings in immortalized GnRH neuronal cells, we hypothesized that Axl and/or Tyro3, but not Mer, would play a role in early GnRH neuronal development.

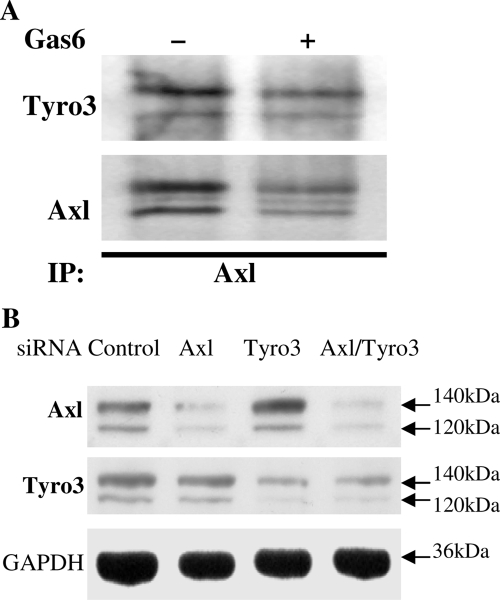

Axl and Tyro3 Form Heterodimers in NLT GnRH Neuronal Cells

Studies in other systems suggest that TAM members form homo- or heteromers to transduce intracelluar signaling in the presence or absence of the Gas6 ligand. To determine whether Axl and Tyro3 might functionally interact to mediate Gas6 signaling in GnRH neuronal cells, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed on lysates of NLT cells incubated in the absence or presence of Gas6 (400 ng/ml for 10 min). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Axl and then probed with anti-Tyro3 or -Axl (Fig. 2A). Tyro3 and Axl formed heterodimers in GnRH neuronal cells in the absence of ligand. There was a slight but consistent decrease in Axl and the Axl/Tyro3 interaction after addition of the ligand Gas6 at 10 min (10–30%, n = 6). This was not changed at 30 min (data not shown) and is consistent with receptor down-regulation after ligand binding. Thus, both homo- or heterodimers of Axl and Tyro3 exist in GnRH NLT neuronal cells.

Figure 2.

Dissecting the Individual Roles of Axl and Tyro3 in GnRH Neuronal Cells

A, Tyro3 and Axl form heterodimers in GnRH neuronal cells. After 10 min incubation in the absence or presence of 400 ng/ml Gas6, NLT lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Axl and then immunoblotted with anti-Axl or anti-Tyro3. B, siRNAs inhibit Axl and Tyro3 in GnRH neuronal cells. NLT cells were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA specific for Axl, Tyro3, or both. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblot and probed with antibodies for Axl, Tyro3, and GAPDH (as a loading control).

Silencing of Axl and Tyro3 to Evaluate Their Roles in GnRH Neuronal Survival and Migration

To assess the relative contributions of Axl and Tyro3 to Gas6-induced signaling, we obtained silencing oligonucleotides designed to knock down Axl or Tyro3 expression in NLT cells. Transfection of specific small interfering RNA (siRNA)-Axl significantly reduced the amount of detectable Axl protein but did not affect Tyro3 levels (Fig. 2B). In contrast, knockdown with siRNA-Tyro3 strongly decreased levels of Tyro3 but not Axl. Knockdown of both resulted in significant 50–90% inhibition of both Axl and Tyro3 protein. Control (scramble) siRNA expression in NLT cells had no effect on Axl and Tyro3 protein detection by immunoblot. NLT neuronal cells with silenced gene expression together with control cells then provided a model system to examine the relative role of Axl and Tyro3 in functional response to Gas6.

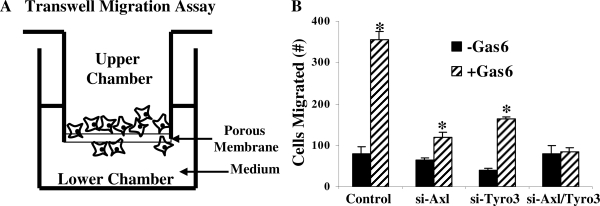

Role of Axl and Tyro3 in Gas6-Induced GnRH Neuronal Cell Migration

We previously observed that NLT cells (which express Axl and Tyro3) possessed the ability to migrate toward 400 ng/ml Gas6 in a modified transwell chamber migration assay in comparison with GT1-7 cells (which express Tyro3 and Mer but not Axl) (33). The response was blocked by the extracellular domain of Axl or Axl antisera, strongly suggesting that Gas6-induced migration was mediated by Axl signaling. We also observed that NLT cells but not GT1-7 cells exhibited a basal level of migration that was independent of Gas6 ligand. These data would argue that endogenous ProS1 in the neuronal cells is not a potent ligand to promote migration because equal levels are present in both NLT and GT1-7 cells. To test the hypothesis that Gas6 signaling to Axl and Tyro3 mediated GnRH neuronal cell movement, migration assays were performed in NLT neurons where Tyro3, Axl, or both were silenced (Fig. 3). After transfection with or without specific siRNAs (as described above), NLT neuronal cells were incubated in transwell chambers overnight in the presence or absence of 400 ng/ml Gas6. Control neuronal cells expressing scrambled siRNAs exhibited robust migration toward Gas6 (4.4-fold, P < 0.05 from control). Knockdown of Axl decreased Gas6-induced migration (1.8-fold from untreated and 1.5-fold from scrambled siRNA control), whereas knockdown of Tyro3 resulted in 50% loss of basal migration as well as an effect on the response to Gas6 (4.1-fold compared with untreated, 2.0-fold from scrambled siRNA control; P < 0.05). Silencing of both Axl and Tyro3 had no effect on basal GnRH neuronal migration but completely abrogated the ability of NLT cells to respond to Gas6 (1.1-fold from without Gas6 and scrambled siRNA control; P not significant). These data support a hypothesis that Axl mediates Gas6-mediated GnRH neuronal cell migration. Tyro3 contributes to a lesser extent possibly via heterodimer formation with Axl because in GT1-7 GnRH cells that express Tyro3 and Mer, but no Axl, Gas6 does not trigger neuronal migration (33).

Figure 3.

Contribution of Axl and Tyro3 to Gas6-Mediated Activation of Migration in NLT GnRH Neuronal Cells

A, Schematic presentation of transwell migration assay. B, Functional effects of silencing Axl, Tyro3, or both on Gas6-induced NLT GnRH neuronal migration (see Materials and Methods for details). *, P < 0.05; n = 3.

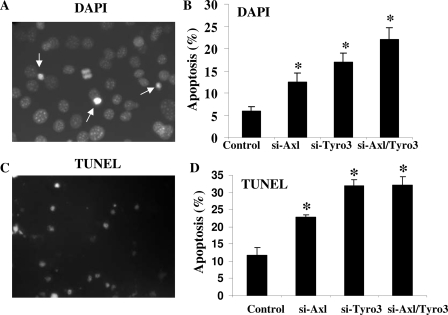

Axl and Tyro3 Both Contribute to Gas6-Induced Survival of GnRH Neuronal Cells

Previous work suggested that Gas6/Axl signaling through ERK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase via Akt mediated NLT GnRH neuronal survival (16). To assess the relative role of Axl and Tyro3 in mediating Gas6-induced GnRH neuronal cell survival, NLT GnRH neuronal cells were transfected with scrambled control or siRNAs specific for Tyro3, Axl, or both and rates of apoptosis assessed. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were exposed to serum-free medium for 24 h. Apoptotic neuronal cells were measured by counting the number of cells with condensed or fragmented chromatin using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (Fig. 4, A and B). Control cells exhibited levels of programmed cell death (5.5%) that were higher than when incubated with Gas6 (1% data not shown). Inhibition of Axl or Tyro3 expression individually resulted in increased numbers of apoptotic cells (12 and 17%, respectively). NLT neuronal cells with both Axl and Tyro3 expression silenced showed even higher levels of apoptosis (22%, P < 0.05 from control). To confirm those data, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed. Because absolute rates of apoptosis detected by this method were lower at earlier time points (data not shown), NLT neuronal cells were starved for 96 h, and apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL (Fig. 4, C and D). With withdrawal of growth factors, 11.7% of control cells were TUNEL positive. Inhibition of Axl or Tyro3 expression individually resulted in significant increased numbers of apoptotic cells (22.8 and 31.9%, respectively; P < 0.05 from control). NLT neuronal cells with both Axl and Tyro3 expression silenced showed similar levels of apoptosis as siTyro3 (32.0%, P < 0.05 from control). These data support the hypothesis that Tyro3 as well as Axl contribute to protection of GnRH neuronal cells from growth factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis and suggest that silencing of Tyro3 caused a more dramatic increase in the rates of apoptosis than did Axl.

Figure 4.

Effects of Silencing Axl and Tyro3 to Rates of Programmed Cell Death in GnRH Neuronal Cells

Photomicrographs of NLT neurons assessed for DAPI staining (A) or TUNEL (C) to detect apoptotic nuclei. Summary of the functional effects of silencing Axl, Tyro3, or both on rates of apoptosis in response to serum deprivation as assessed by DAPI (B) or TUNEL (D) (see Materials and Methods for details). *, P < 0.05; n = 3.

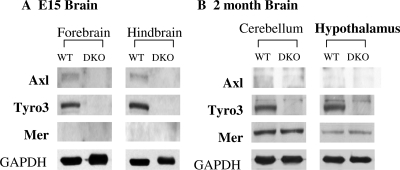

TAM Family Members Are Differentially Expressed in Embryo and Adult Mouse Brain Regions

To confirm the functional role of TAM family members in GnRH neurons, we evaluated the impact of their loss in vivo. Colonies of Axl−/− knockout (Axl KO), Tyro3−/− knockout (Tyro KO), and Axl−/−, Tyro3−/− double knockout (DKO) mice in a C57BL/6 × 129sv background (29) were established. E15 heads from wild-type (WT) and DKO litters were bisected into anterior (containing forebrain) and hind (containing progenitor cerebellum) to evaluate developmental expression (Fig. 5A). Hypothalami and cerebellums were dissected from 2-month-old adult WT and DKO mice brains to evaluate adult expression (Fig. 5B). Lysates obtained from the tissues were analyzed by immunoblot probed with antibodies specific for Axl, Tyro3, and Mer as well as GAPDH.

Figure 5.

Expression of TAM Family Member Protein Levels in Brains of E15 and Adult WT and DKO Mice

A, Expression of Axl, Tyro3, and Mer in the forebrain and hindbrain regions of E15 WT but not DKO mice. B, Differential expression of Axl, Tyro3, and Mer in brain regions from WT and DKO mice at 2 months of age. See Materials and Methods for details.

Tyro3 and Axl were expressed in WT anterior and hindbrain samples from E15 lysates, whereas Mer was not detected. In contrast, Tyro3 and Mer protein were expressed in the WT adult cerebellum and hypothalamus, but Axl protein was not detected. As expected, none of the tissues from DKO mice expressed Axl or Tyro3 protein. Mer was appropriately expressed in the adult but not the embryonic DKO tissues. Importantly, deletion of Axl and Tyro3 did not result in an up-regulation of Mer in the adult hypothalamus. Taken together, these data are consistent with a pattern of expression of Axl in early forebrain development at the time the GnRH neurons are migrating but not in the adult hypothalamus. Tyro3 is present across development and in the adult, and Mer is expressed only in the adult hypothalamus.

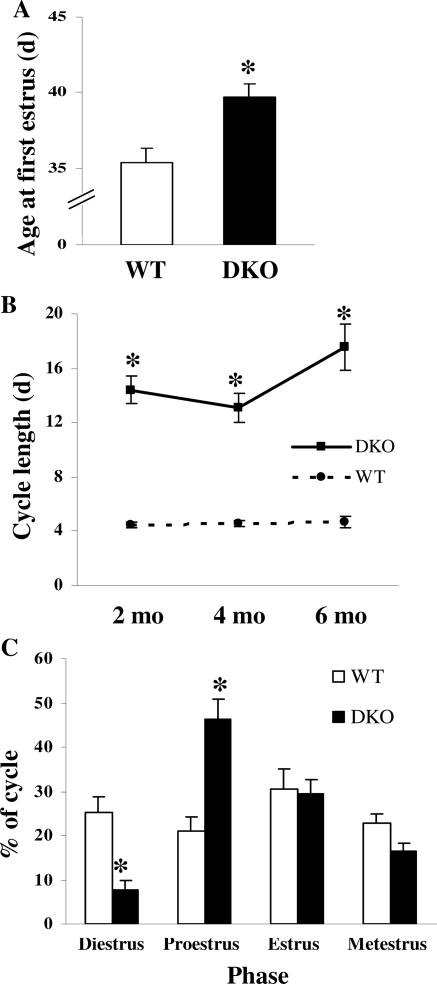

Loss of Axl and Tyro3 Expression Disturbs Reproductive Development and Function in Female Mice

Initial reports had suggested that female mice with single and double knockouts of TAM family members had no obvious reproductive phenotype (29), but recent reports suggest deletion of Mer induces distal vaginal atresia (32). Indeed, we found that females absent for Axl, Tyro3, or both were fertile and able to deliver healthy litters of normal-size pups compared with WT. To detect more subtle roles of Axl and Tyro3 in reproductive function, we evaluated the age of vaginal opening, age of first estrus, and estrus cyclicity in DKO and WT mice.

Vaginal opening is dependent on cumulative tonic GnRH-induced gonadotropin activation of ovarian estrogen production. Female pups were evaluated daily for vaginal opening starting within 1 wk of weaning (21–28 d of age). Once vaginal opening was observed, vaginal cytology was examined by collecting vaginal smears daily until estrus occurred. DKO mice were noted to have vaginal opening at 34.1 ± 0.4 d (n = 18), which was not different from WT mice (33.9 ± 0.7 d; n = 12; P not significant). These results suggest that timing of vaginal opening is not compromised in the absence of both Axl and Tyro3. In contrast to vaginal opening, first estrus requires formally orchestrated changes in GnRH-induced gonadotropin and sex hormone production. DKO mice were noted to have a delayed first estrus by 4 d (39.7 ± 1.3 d; n = 17) compared with WT mice (35.4 ± 0.9 d; n = 10; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Axl and Tyro3 Impact on the Process of Sexual Maturation in Female Mice

A, DKO mice (n = 17) have delayed first estrus compared with WT controls (n = 10). *, P < 0.05. B, DKO mice have prolonged irregular estrous cycle length at 2, 4, and 6 months. *, P < 0.05 (n = 10 for DKO time points; n = 4 for WT time points). C, DKO mice (n = 10) have increased proestrous and decreased diestrous phase lengths compared with WT mice (n = 4) at 2 months. *, P < 0.05.

After sexual maturation, fertility and reproductive competence ultimately depend on normal estrous cyclicity. The timing of regular estrous cyclicity appears to be dependent on the appropriate expression of Axl and Tyro3. In contrast to WT mice, DKO mice were observed to have markedly irregular estrous cycles as early as 2 months, ranging in length from 5–16 d (average 8.5 ± 1.1 d; n = 10) and differed significantly from WT cycles (4.5 ± 0.2 d; n = 4; P = 0.05; Fig. 6B). The cycles of WT mice averaged 4.6 ± 0.2 and 4.7 ± 0.4 d at 4 and 6 months of age, respectively. The cycles of DKO mice continued to be irregular and prolonged in length and averaged two to three times longer (12.9 ± 1.7 d, n = 10, and 9.9 ± 1.0 d, n = 10, respectively, at 4 and 6 months of age), suggesting the defect in hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function was a result of abnormalities apparent with sexual maturation. In addition, many animals had prolonged proestrous phase of the cycle (Fig. 6C). DKO mice spent more than twice as much time in proestrus compared with WT mice (P < 0.01) with decreased time in diestrus (P < 0.05; n = 10).

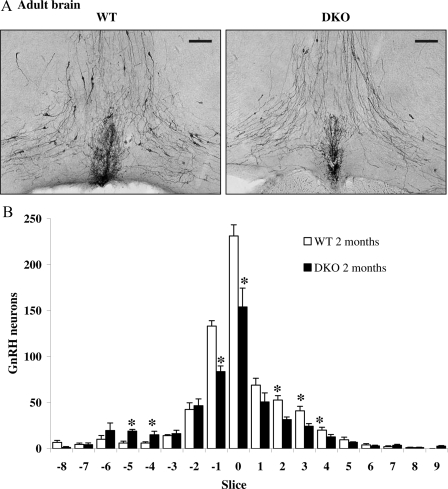

GnRH Neuron Populations Are Decreased in DKO Adult Females

Because the analysis of the reproductive function of DKO mice suggested a central defect in the ability to mount a proper GnRH-induced LH surge, we examined the pattern of the GnRH neuronal network in adult WT and DKO mice. Brains from perfused DKO and WT 2-month-old mice were sectioned coronally (from the rostral diagonal band of Broca region to the caudal hypothalamus) and examined for immunoreactive GnRH as indicated by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine reaction product and bright-field microscopy (Fig. 7A). Neurons containing immunoreactive GnRH were counted in each section by an investigator blinded to treatment group. Brains from DKO females had a 24% decrease in the total number of GnRH neurons compared with WT (from 651.8 ± 16 in WT, n = 5, to 494.2 ± 30 in DKO, n = 4; P < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Two-Month-Old Axl/Tyro3-Null Mice Have Decreased Numbers of GnRH Neurons in the Hypothalamus

A, Images of immunoreactive GnRH neurons in WT (n = 4) and DKO (n = 5) mice taken at ×200 with the OVLT shown in the bottom center of each image. B, Brains from DKO mice had fewer immunoreactive GnRH neurons compared with WT in slices −1, 0, and +2–3 but more in slices −5 and −4. GnRH neuron counts were obtained in slices that represent 330 μm each, with OVLT labeled as zero (see Materials and Methods for details). *, P < 0.05.

To identify potential regional effects of Axl/Tyro3 deletion on the GnRH neuronal system, the number of GnRH neurons were mapped in relation to their positions in the forebrain in the DKO compared with the WT controls (Fig. 7B). GnRH neuron counts were aligned with position zero at the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT) at the opening of the third ventricle. One slice consisted of a series of six consecutive sections of 55 μm each. In addition to the overall decrease in the number of GnRH neurons, a two-way ANOVA with location as a repeated measure revealed the strong dependence of cell loss on location (genotype × location interaction; P < 0.01). The majority of the missing cells in DKO brains were from regions surrounding the OVLT (34% decrease in GnRH neurons counted in slices −1 to +4). There was a small but significant increase in GnRH cell number in more rostral positions (−5 and −4) in DKO brains that may indicate a defect in neuronal migration. However, the loss of cells in the OVLT region was not completely compensated by the appearance of cells in different positions. Together these data suggest a defect in GnRH neuronal survival and migration in the adult brains of mice lacking Axl and Tyro3.

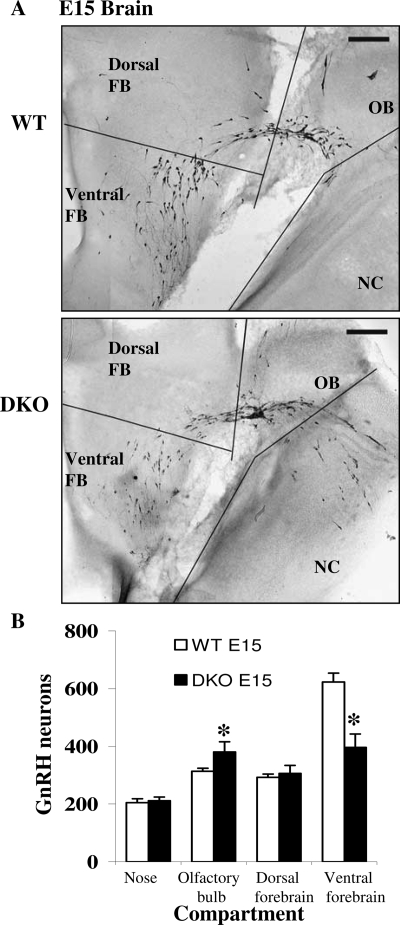

GnRH Neuron Distribution Is Disrupted in DKO Embryos

To determine whether the loss of GnRH neurons in the DKO brains occurred before or after developmental GnRH neuronal migration, the total number and distribution of GnRH-positive neurons in WT and DKO embryo brains was evaluated at E15, a time when the GnRH neuronal population is moving across the cribriform plate into the forebrain (7). WT and DKO embryo heads (n = 5) were sectioned sagittally, and an investigator blind to treatment group counted GnRH-positive neurons (Fig. 8). In addition to determining the total number of GnRH-positive neurons, their distribution along the migration pathway was also determined, including their origin in the nose, along the nasal vomeronasal nerve, across the cribriform plate to the olfactory bulb, and further into the forebrain where cells were considered as dorsal or ventral (34). Subdivision of the plane of migration by compartment (nose, olfactory bulb, and dorsal and ventral forebrain) showed strong regional differences in cell number dependent upon genotype (Fig. 8). The total number of GnRH neurons in DKO embryos (1295 ± 45) was only 10% less than in WT embryos (1433 ± 47). Analysis of the number of GnRH neurons in different compartments (two-way ANOVA by genotype and location as a repeated measure) revealed a significant main effect of region [F(3,24) = 41.3; P < 0.01]. The effect of genotype alone only approached significance [F(1,8) = 4.5; P = 0.067]. Importantly, there was a highly significant statistical interaction of genotype in relation to location [F(3,24) = 11.08; P < 0.01]. A closer examination of the regional compartments revealed a significant 36% reduction of the number of GnRH neurons selectively in the ventral forebrain (396 ± 47 in DKO compared with 623 ± 31 in WT; P < 0.01), whereas the population in nose and dorsal forebrain appeared unaffected (Fig. 8C). A 22% increase in the olfactory bulb region in DKO compared with WT did reach statistical significance (P < 0.05) but cannot account in a compensatory manner for the reduction in the ventral forebrain. Thus, the loss of immunoreactive GnRH neurons in the E15 brains was most dramatic in the compartment that comprises the final destination of GnRH neurons, the ventral forebrain. The trend toward more GnRH neurons detected in the compartment immediately anterior to the forebrain may relate to a migratory defect in a subset of neurons. Together, these results demonstrate that a subpopulation of GnRH neurons in DKO mice are absent or fail to express GnRH as early as E15 and that these defects may be a consequence of premature apoptosis and/or migration after the cribriform plate region rather than an early loss of neurons in the nose.

Figure 8.

GnRH Neuronal Number and Position Are Altered in E15 DKO Brains

A, Low-magnification images of immunoreactive GnRH neurons in WT and DKO E15 heads showing the locations of the compartments that were counted. FB, Forebrain; NC, nasal compartment; OB, olfactory bulb. B, Altered distribution of GnRH neurons in separate compartments of E15 DKO brains (n = 5 for both genotypes). *, P < 0.05.

Increased Rates of Apoptosis along the GnRH Migratory Route in DKO Mice

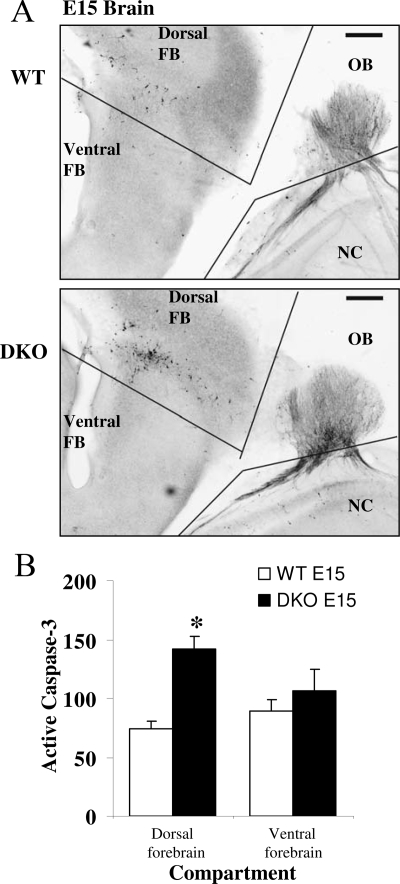

To support our hypothesis that GnRH neurons were actually lost via programmed cell death rather than immunologically undetectable due to reduced expression of the GnRH gene, E15 brains were assessed for rates of apoptosis using caspase 3 cleavage analysis (Fig. 9). Caspase 3 is an integral step in the intrinsic pathway of programmed cell death. Activation of caspase 3 results in cleavage of the protein. Antibodies derived to detect cleaved caspase were used to detect dying cells in embryonic WT and DKO brains. Analysis revealed a selective 1.8-fold increase in the number of cells containing activated caspase 3 in the dorsal forebrain of DKO mice compared with WT, consistent with the location of loss of GnRH neuron number during migration. Although dual immunohistochemistry was not performed, the pattern of the cleaved caspase 3 cleavage paralleled that of the GnRH migratory route and was confirmed with a second antibody (data not shown). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that Tyro3 as well as Axl mediates cellular responses to Gas6 to promote neuronal migration and survival in GnRH neuronal cells and therefore can contribute to GnRH neuronal cell survival and migration in vivo.

Figure 9.

Apoptosis in Vivo in DKO Compared with WT Embryonic Mice

Photomicrographs of sagittal sections of E15 brain showing cleaved caspase 3 immunoreactivity in WT (A) and DKO (B). C, Results of analysis of active caspase 3 cleavage in counts of cells in dorsal and ventral forebrain of WT (white bars) and DKO (black bars). n = 5; *, P < 0.05 from WT control.

DISCUSSION

The TAM family of receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligands, Gas6 and ProS, are widely distributed in the immune, nervous, and reproductive systems and where coexpression of different family members has made dissection of their relative cell-specific roles difficult (21). Prieto and co-workers (26,27,35) examined the mRNA expression profiles of the TAM members across rodent brain development and noted regional differences in expression. Analysis of TAM expression in immortalized GnRH neuronal cells showed that Axl and Tyo3 protein is expressed in the NLT cells, a model of migrating GnRH neurons, whereas Mer and Tyro3 are expressed in the postmigratory GT1-7 cells, in agreement with a hypothesis that Axl and Tyro3 impact on GnRH neuronal migration and survival. Based upon the expression profile in the GnRH neuronal cells, the current study examined the reproductive phenotype of the Axl/Tyro3-null 2-month-old females and observed subtle but significant abnormalities. Although overall fertility and birth rates were normal, additional maturation and precise function of the axis in the female was impaired. Consistent with recent studies that suggested that Mer but not Axl or Tyro3 deletion results in distal vaginal atresia (32), we saw no abnormalities in the DKO mice in the timing of vaginal opening. First estrus, which is dependent on a normal GnRH-induced LH surge mechanism, however, was delayed, and estrous cycles were prolonged. Examination of the GnRH neuronal system in vivo indicated that deficits may be related to location-dependent alterations in the number of immunoreactive GnRH neurons. Parallel studies in GnRH neuronal cells characterized further the mechanisms by which TAM family members may alter GnRH neuron migration and survival.

Clinically, women with hypothalamic amenorrhea have irregular cycles presumed to be due to a partial deficit of GnRH production. These women often have impaired fertility because of the dysfunctional timing of ovulation and variable estrogen production. In the current study, many DKO animals were maintained in a prolonged proestrous state that likely resulted in a hormonal pattern similar to that observed in human patients with oligoamenorrhea with tonic estrogen in the absence of appropriate GnRH-induced LH surge and ovulation. Whereas we have assumed that these more subtle reproductive defects are acquired rather than genetic, the phenotype of the Axl- and Tyro3-null mice raises the question as to whether inherited defects in the TAM family might underlie the more subtle reproductive disorders observed in patients presenting with irregular menses and infertility. A recent report by Herbison and co-workers (36) suggested that dramatic loss of immunoreactive GnRH neurons had variable effects on reproductive function. This contrasts with our more subtle but region-specific loss of GnRH neurons, which had significant reproductive consequences. Together these data suggest that it is important to consider that it is the timing, the location, and the degree of loss of GnRH neurons and the compensating abilities of remaining GnRH neurons that impact on GnRH neuron function and reproductive phenotype. Although the system is built with multiple redundancies, there are most likely regional and cell group-specific functions of the GnRH neurons once they reach their final destinations.

To evaluate the mechanism of the altered reproductive function in the DKO mice, the number and location of GnRH neurons in the adult were analyzed, and a significant loss of immunoreactive GnRH neurons was found. The loss was more apparent in the regions surrounding the OVLT (34%), a region noted to be important for the GnRH-induced LH surge (37,38). Further analysis of the GnRH neuronal network during embryogenesis revealed that the defect becomes discernible in utero with a similar 36% impairment in the appropriate targeting and positioning of the neurons in the ventral forebrain by E15. The fact that the neuronal loss in utero and in the adult was not uniform across the highly distributed population suggests that loss of Axl and Tyro3 does not trigger a generalized or random increased rate of neuronal apoptosis. The lack of a difference in GnRH neuronal numbers in the nose suggests that Axl and Tyro3 play a role later in GnRH neuronal ontogeny, perhaps at or soon after crossing the cribriform plate when the GnRH neurons leave the guidance of the vomeronasal nerve fibers and are targeted to forebrain positions. That there was no apparent clustering of neurons at the cribriform plate suggests the defect in the DKO mice is not solely due to a defect in the final phase of GnRH neuron migration into the forebrain. The increased rates of apoptosis in vivo as assessed by activated caspase 3 in similar regions supports the hypothesis that Axl and Tyro3 mediate both the survival and migration of GnRH neurons during development. The fact that the loss of GnRH neurons in the ventral forebrain in the embryonic DKO brains mirrored the defects in the adult supports the hypothesis that the functional reproductive defects originate during development. Although studies in the GnRH-immortalized cells and our previous work (19) suggest the effects of silencing Axl and Tyro3 are mediated directly in subsets of GnRH neurons, the potential loss of TAM member function in adjacent neurons or glia that indirectly impact on GnRH function is not excluded in the analysis of the DKO mice and would require analysis of Axl and Tyro3 selectively in GnRH neurons.

The lack of up-regulation of Mer in the hypothalami of 2-month-old DKO mice suggests that adult Mer expression, if important in the reproductive axis, could not compensate for loss of Axl and Tyro3. Further studies will be necessary to dissect potential roles of Mer and Tyro3 in the adult GnRH neuronal system. Finally, the ligand dependency of the receptor signaling remains to be confirmed. Although initial reports suggested that Gas6-null mice are reproductively normal (39,40), further detailed analysis of these mice will be necessary to clarify whether the effects observed in the DKO mice in this study are dependent on signaling through the Gas6 ligand. The role of ProS1 in the physiological function of the TAM family in GnRH neurons is unexplored.

Many candidates have been implicated in GnRH neuronal migration either through studies in GnRH neuronal cells or from in vivo studies in animal or humans (reviewed in Refs. 4,5,6). They can be classified as inductive chemoattractant signals, cell adhesion molecules and extracellular matrix proteins, growth factors, neurotransmitters, and transcription factors. Some act directly on the olfactory system and thus when disrupted only indirectly modify GnRH neuronal development. Many of the defects observed in animals and humans with Kallmann syndrome can be attributed to disruption of the pathway on which the GnRH neurons migrate from the nose to the cribriform plate (41). The product of the KAL-1 gene, anosmin, is a glycoprotein that is secreted and then tethered to the extracellular matrix (42,43) and for which in one human embryo, disruption resulted in altered GnRH and olfactory neuron tangling anterior to the cribriform plate (2). FGFR1 and FGF8 mutations are found in humans with autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome and may be related to GnRH neuron loss associated with defective olfactory development (reviewed in Ref. 44). Defects in prokineticin2 (PROK2) and its receptor PROKR2 have defective GnRH neuronal migration related to defective olfactory bulb development (45). Similarly nasal embryonic LHRH factor (NELF) functions as a ubiquitous guidance molecule for olfactory axons and GnRH neurons and when disrupted alters the targeting of the GnRH neurons (46).

In characterizing the list of putative molecules that impact more directly on GnRH neuronal development, one can ask where and when they function temporally. A candidate may impact on three phases of GnRH neuronal development: the first phase of movement through the nasal compartment to the cribriform plate; the second phase, crossing the cribriform plate and making the turn along the caudal vomeronasal nerve; and finally, departure of the neurons from the fibers to reach final forebrain targets (5). γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) represents an important neurotransmitter that modifies the rate of movement of GnRH neurons in the nasal compartment (47,48,49,50). Despite being expressed in fewer than one third of GnRH neurons in the region, studies using agonists or antagonists to modify its levels, or transgenically targeted increased expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase-67 (GAD-67) selectively in GnRH neurons revealed roles for the neurotransmitter as an inhibitory influence on the probability of movement of GnRH neurons in the nasal compartment and attachment to guiding fibers in the forebrain. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) (also refered to as chemokine CXC motif ligand 12) via its receptor, chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 4 (CXCR4), may attract GnRH neurons via a gradient in the nasal compartment and may play a critical role in early GnRH neuronal migration and survival (51). Similarly, hepatocyte growth factor signaling through c-Met has been suggested to impact on early GnRH neuronal migration (52,53). To date, no defects have been reported in humans in these pathways.

Dual deletion of TAM family members Axl and Tyro3 results in a GnRH neuronal network phenotype that appears late in the developmental sequence. The locus of the defect appears to be at or after cribriform plate migration and involves both an increase in programmed cell death and a defective terminal migration. Whenever assessing a potential loss of GnRH neurons, one must consider the possibility that genetic or other manipulation may result in a loss of GnRH synthesis in a normal number of neurons, because we have no other marker of GnRH neurons in vivo. However, because overexpression of Axl in GT1-7 cells represses GnRH expression, silencing of Axl in the DKO model is not expected to inhibit GnRH neuronal detection but should instead enhance it. The region-specific increased rates of apoptosis as assessed by activated caspase 3 detected in DKO mice compared with controls confirms a loss of GnRH neurons. Thus, these data support a major role for Axl and Tyro3 influencing GnRH neuronal ontogeny. Additional studies in the NLT GnRH neuronal cells showed that Axl/Tyro3 heterodimers are present in the absence of ligand Gas6 with no modification of the interaction when ligand was added. Together with the silencing studies, the data support a model where Axl homodimers and Axl/Tyro3 heterodimers mediate early GnRH development and that their deletion results in a defect in normal maturation of the central aspects of female reproductive axis. Although Mer is expressed in the adult hypothalamus, it does not compensate for the developmental defects due to loss of Axl and Tyro 3 together with the lack in the adult. Additional studies are needed to analyze the roles of Tyro3 and Mer in adult GnRH neuronal function.

Taken together, the experiments in the current study support the functional significance of the TAM family of receptor tyrosine kinases in female reproductive competence. Although patients with more subtle disorders of GnRH-induced gonadotropin secretion were commonly thought to have acquired environmental defects, these data together with recent studies showing digenic mutations in humans with GnRH deficiency (54) suggest that research should focus on the possibility that concomitant genetic mutations underlie more subtle alterations in GnRH function to impact on normal reproductive competence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Full-length recombinant Gas6 was provided by B. Varnum at Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Axl 318 antibody was a gift from Paola Bellosta at New York University Medical Center. Affinity-purified Axl antibody was designed by our lab and made by Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO). Axl (M-20) antibody and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antigoat antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Tyro3 antiserum was a generous gift from Cary Lai at The Scripps Research Institute. Mer antibody was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). GAPDH antibody and anti-caspase 3 were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA) and R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (donkey antirabbit IgG and sheep antimouse IgG) were purchased from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp. (Piscataway, NJ). Anti-GnRH was purchased from Affinity Bioreagents and biotinylated anti-rabbit second antibody from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Vectashield HardSet Mounting Medium with DAPI was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL system was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

DNA Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from NLT and GT cells (three different batches of each) using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified using RNEasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). cDNA and cRNA were made using 2 μg total RNA and the One-Cycle eukaryotic target labeling assay (Affymetrix, Valencia, CA); 20 μg cRNA was used for labeling. To ensure intact RNA, both total RNA and cRNA integrity was verified using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer in the University of Colorado Denver Cancer Center Array Core. The microarrays were performed using the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array chip containing 45,000 probe sets representing over 39,000 transcripts and variants from over 34,000 well characterized mouse genes. Analysis of results was performed using GeneChip operating software (GCOS) (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) to compute the cell intensity from the image data, filter the data, and compare each NLT to each GT sample. GeneSpring (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) software was also used for further statistical analysis, normalizing data from different chips using multifilter comparisons. GeneSpring normalized data using a per-chip method where each measurement was divided by the 50th percentile of all measurements in the same array.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from NLT or GT cells using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). RNA (0.5 μg) was reverse transcribed using Thermo Verso cDNA kit (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). RT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: 94 C for 3 min; 94 C for 45 sec, 56 C for 45 sec, and 72 C for 1 min for 35 cycles; and 72 C for 10 min. Primer sequences for amplifying Axl were 5′-CCCCTGAGAACGTTAGCG-3′ and 3′-TGCTCTGCAGTACCATCTAGC-5′. The primer sequences for amplifying Tyro3 were 5′-CGATCTCCAGCTACAACGC-3′ and 3′-GCATGGCTGAGTCCGGAAT-5′. The primer sequences for amplifying Mer were 5′-CTGCACAGTGAGAATCGCG-3′ and 3′-GCCTGGCTCAGATGTGTTCG-5′. Primer sequences for amplifying Gas6 were 5′-CCAGACCTGCCAAGATATCG-3′ and 3′-GCCATGTTACCGCAACCC-5′. Primer sequences for amplifying ProS1 were 5′-GGCACAGCTGTGCAAGAA-3′ and 3′-CGGGTTCTAGTCTTCTCAAC-5′. The quantity of Axl, Tyro3, Mer, Gas6, and ProS1 mRNA was normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA. The primer sequences for amplifying GAPDH were 5′-CGACCCCTTCATTGACCTCA-3′ and 3′-GCCACGACTCATACAGCACC-5′.

siRNA

Four siRNAs separately targeting Axl and Tyro3 were designed and made using siRNA Target Finder and Silencer siRNA Construction Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). NLT cells were grown in complete medium to 80% confluence in six-well plates and then transfected with siRNAs (final concentration, 100 nm) using Lipofectamine Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) or DharmaFect1 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) following the protocols. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblot or other functional studies. The sequences used for Axl knockdown were sense 5′- AATCAGTGTGTTCTCCAAGTCCCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-AAGACTTGGAGAACACACTGACCTGTCTC-3′. The sequences used for Tyro3 knockdown were sense 5′-AAGGTACATGAGATCATACACCCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-AAGTGTATGATCTCATGTACCCCTGTCTC-3′. The sequences for control siRNAs were sense 5′-AAAGTTGTCGAATCTCTGCTACCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-AATAGCAGAGATTCGACAACTCCTGTCTC-3′.

Immunoblot and Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Cells were lysed in 1× RIPA buffer [[sqb]150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 59 mm Tris (pH 8.0)] (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) and freshly added 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 20 mm Na3VO4, and 25 mm NaF (Fisher). Protein lysates were quantified using BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). An aliquot of 20–50 μg total protein was resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE gels using a Bio-Rad mini-gel system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Subsequently, proteins were transferred to Hybond polyvinylidene difluoride (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) using a Bio-Rad mini transblotter system. The membranes were blocked in 5% milk, TBS-T buffer [20 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.6), 137 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20] for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted to 1:500 to 1:2000 in 5% milk and incubated with the membranes at 4 C overnight. The membranes were washed in TBS-T three times for 10 min each. The HRP-linked secondary antibodies were diluted to 1:3000 in TBS-T and incubated with the membranes for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed as above and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) immunodetection reagents (Amersham).

For immunoprecipitation analysis, NLT neuronal cells in 10-cm plates were starved in DMEM lacking serum for 6 h. Cells were then treated or not treated with 400 ng/ml Gas6 for 10 min and harvested in 1× RIPA (200 μl). Lysates (200 μg) were incubated with Axl antibody (Santa Cruz) on a rocker at 4 C overnight. Protein G Plus-agarose (30 μl) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added and incubated for 3 h. Beads were washed five times with cold PBS, boiled in 20 μl Laemmli loading buffer (Bio-Rad) for 5 min, and subjected to immunoblot analysis with either Axl antibody (Santa Cruz) or Tyro3 antibody.

Apoptosis Assay

NLT cells were transiently transfected with control, Axl-specific, Tyro3-specific, and both Axl- and Tyro3-specific siRNAs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were plated on coverslips in serum-free medium for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde/PBS (Polysciences, Inc, Warrington, PA) for 30 min at room temperature, permeabilized in 5% BSA/0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and stained with Texas Red-x Phalloidin (25 μl/ml) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Between each reagent, cells were washed with PBS three times. Coverslips were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI (Vector). Apoptotic cells were measured by counting the number of cells with condensed or fragmented chromatin. Four fields at ×200 magnification were counted. Duplicate coverslips in three separate experiments were evaluated. The rate of apoptosis was expressed as a percentage of total counted cells.

TUNEL Assay

NLT cells were transiently transfected with control, Axl-specific, Tyro3-specific, and both Axl- and Tyro3-specific siRNAs in a 16-well Lab-Tek chamber slide. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were starved in DMEM lacking serum for 96 h. DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL assay (Promega) was then performed as described in the protocol. Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 25 min at 4 C and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 5 min. After being rinsed with PBS, cells were equilibrated in equilibration buffer at room temperature for 10 min and then incubated with recombinant terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase incubation buffer at 37 C for 1 h. Reaction was stopped by 2× standard saline citrate at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were washed with PBS and mounted with Vectashield plus DAPI. Apoptotic cells (green) were counted using a fluorescein filter (520 nm) and total cells (blue) were counted using a 460-nm filter. About 1000 total cells were counted for each condition. The rate of apoptosis was expressed as a percentage of total counted cells.

Transwell Migration Assay

NLT cells were transiently transfected with control, Axl-specific, Tyro3-specific, and both Axl- and Tyro3-specific siRNAs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were starved in serum-free DMEM for 5 h. Cells were trypsinized, resuspended in DMEM, and counted. Cells (50,000 in 100 μl serum-free medium per well) were then plated into the upper chamber of a 24-well transwell (Fisher). Cells were exposed in the absence or presence of Gas6 (400 ng/ml) as an inducer of migration in serum-free medium (1 ml) in the lower chamber. After incubation at 37 C in humidified 5% CO2 for 16–18 h, cells were fixed and stained using Diff-Quik Stain Set (Dade Behring Inc., Newark, DE). The number of migrated cells for each condition was determined by counting four fields at ×200 magnification on each membrane. Duplicate membranes in three separate experiments were evaluated.

Animals

Axl- and Tyro3-null mice established in a C57BL/6 × 129sv background (29) were bred to create Axl/Tyro3-null double transgenics (DKO). Animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female mice were housed in microisolator cages in the same room as males (similarly housed) under a 12-h light cycle with food and water ad libitum. All mice were genotyped at time of weaning.

Estrous Studies

Female pups were checked once daily for vaginal opening starting within 1 wk of weaning, at which time vaginal cytology was examined by collecting vaginal smears daily until estrus was observed. Vaginal smears for cycle length were collected daily at the same time for at least 12 d and stained with toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich). Smears were classified as diestrus, proestrus, estrus, or metestrus; cycle length was calculated as the number of days from the beginning of one estrous phase to the beginning of the next.

Perfusion and Immunohistochemistry

Adult mice were anesthetized with 10 mg/kg xylazine and 100 mg/kg ketamine between 0800 and 1000 h. Each mouse was perfused intracardially with 2000 U heparin followed by 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 7.4). Brains were dissected out and immersed in 4% formaldehyde overnight and then stored in 0.1 m PB at 4 C. Timed-pregnant mice were anesthetized as described; embryos were removed one at a time and perfused intracardially with 2 ml 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 m PB. Heads were removed and immersed in 4% formaldehyde overnight and then stored in 0.1 m PB at 4 C.

Perfused tissues were embedded in 5% agarose; adult brains were cut coronally into 55-μm sections on a Leica VT 1000S vibrating blade microtome; embryo heads were cut sagittally at 65 μm. Sections were treated with 0.5% sodium borohydride, blocked in 5% normal goat serum with 0.5% Triton X-100 and incubated in 1:10,000 (adult brains) or 1:1000 (embryo heads) anti-GnRH for 72 h followed by 1:1000 biotinylated antirabbit second antibody for 2 h and 1:2500 HRP-streptavidin for 1 h. Sections were developed with 0.025% diaminobenzidine (Sigma). Tissue sections were mounted onto plain glass slides and coverslipped with Permount mounting medium (Fisher).

Immunoreacted sections were examined at ×200 on a Zeiss Axiovert microsope using bright-field illumination, and neurons positive for GnRH were counted manually. In adults, GnRH-positive neurons were analyzed by slice; each slice was comprised of six 55-μm sections (330 μm total thickness). Slice 0 was centered on the OVLT at the third ventricle. Negatively numbered slices corresponded to slices rostral to OVLT, whereas positively numbered slices corresponded to slices caudal to the OVLT. In E15 brains, GnRH-positive neurons were analyzed by compartment: nose, olfactory bulb, dorsal forebrain, and ventral forebrain (34,55). The cribriform plate formed the boundary between the nasal compartment and the olfactory bulb/dorsal forebrain. An imaginary line drawn from the caudal tip of the cortex along the ventral surface of the cortex to the base of the olfactory bulb formed the boundary between the dorsal forebrain and the ventral forebrain.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± sem for each group. Statistical differences between the means of two groups were tested using unpaired t test. Differences between groups for neurons in different locations were analyzed using two-way ANOVA considering location as a repeated measure, and post hoc significance at any one location was evaluated by examining the 95% confidence interval for the means at each location. P values were reported as <0.05 or <0.01. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Software QuickCalcs Online Calculators for Scientists (www.graphpad. com; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA), Microsoft Office Excel 2003 version 11 (Microsoft Corp., Remond, WA), and SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Acknowledgments

The DNA array experiments were performed with the assistance of the University of Colorado Denver Cancer Center Microarray Array Core. We thank Brandon Wadas and J. Gabriel Knoll for help with immunocytochemical procedures.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants HD31191 (M.E.W.) and DC009034 (S.A.T.).

Disclosure Statement: Authors A.P., B.B., M.X., S.N.-P., G.L., S.T., and M.E.W. have nothing to declare.

First Published Online September 11, 2008

Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; DKO, double knockout; E10, embryonic d 10; Gas6, growth arrest specific gene 6; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; KO, knockout; OVLT, organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis; PB, phosphate buffer; ProS1, protein S; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling; WT, wild type.

References

- Wray S, Hoffman G 1986 Postnatal morphological changes in rat LHRH neurons correlated with sexual maturation. Neuroendocrinology 43:93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Bick D, Pfaff DW 1989 Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH)-expressing cells do not migrate normally in an inherited hypogonadal (Kallmann) syndrome. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 6:311–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Tobet SA, Crandall JE, Jimenez TP, Schwarting GA 1995 The migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in the developing rat is associated with a transient, caudal projection of the vomeronasal nerve. J Neurosci 15:7769–7777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Schwarting GA 2006 Recent progress in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Endocrinology 147:1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Wierman ME, Tobet SA 2007 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Semin Reprod Med 25:305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierman ME, Pawlowski JE, Allen MP, Xu M, Linseman DA, Nielsen-Preiss S 2004 Molecular mechanisms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TJ, Gibson MJ, Rogers MC, Silverman AJ 1997 New observations on the development of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system in the mouse. J Neurobiol 33:983–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallman F SW, Barrera S 1944 The genetic aspects of primary eunuchoidism. Am J Ment Defic 48:203–236 [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb RW, Crowley Jr WF 1990 Diagnosis and treatment of isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadman SM, Kim SH, Hu Y, Gonzalez-Martinez D, Bouloux PM 2007 Molecular pathogenesis of Kallmann’s syndrome. Horm Res 67:231–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radovick S, Wray S, Lee E, Nicols DK, Nakayama Y, Weintraub BD, Westphal H, Cutler Jr GB, Wondisford FE 1991 Migratory arrest of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:3402–3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon PL, Windle JJ, Goldsmith PC, Padula CA, Roberts JL, Weiner RI 1990 Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron 5:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellosta P, Costa M, Lin DA, Basilico C 1995 The receptor tyrosine kinase ARK mediates cell aggregation by homophilic binding. Mol Cell Biol 15:614–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C, Lemke G 1991 An extended family of protein-tyrosine kinase genes differentially expressed in the vertebrate nervous system. Neuron 6:691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Xiong X, James A, Gordon DF, Wierman ME 1998 Identification of novel factors that regulate GnRH gene expression and neuronal migration. Endocrinology 139:3654–3657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MP, Zeng C, Schneider K, Xiong X, Meintzer MK, Bellosta P, Basilico C, Varnum B, Heidenreich KA, Wierman ME 1999 Growth arrest-specific gene 6 (Gas6)/adhesion related kinase (Ark) signaling promotes gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal survival via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Akt. Mol Endocrinol 13:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MP, Xu M, Linseman DA, Pawlowski JE, Bokoch GM, Heidenreich KA, Wierman ME 2002 Adhesion- related kinase repression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression requires Rac activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 277:38133–38140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Preiss SM, Allen MP, Xu M, Linseman DA, Pawlowski JE, Bouchard RJ, Varnum BC, Heidenreich KA, Wierman ME 2007 Adhesion-related kinase induction of migration requires phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and ras stimulation of rac activity in immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal cells. Endocrinology 148:2806–2814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MP, Xu M, Zeng C, Tobet SA, Wierman ME 2000 Myocyte enhancer factors-2B and -2C are required for adhesion related kinase repression of neuronal gonadotropin releasing hormone gene expression. J Biol Chem 275:39662–39670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linger RM, Keating AK, Earp HS, Graham DK 2007 TAM receptor tyrosine kinases: biologic functions, signaling, and potential therapeutic targeting in human cancer. Adv Cancer Res 100:35–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G, Rothlin CV 2008 Immunobiology of the TAM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 8:327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfioletti G, Brancolini C, Avanzi G, Schneider C 1993 The protein encoded by a growth arrest-specific gene (gas6) is a new member of the vitamin K-dependent proteins related to protein S, a negative coregulator in the blood coagulation cascade. Mol Cell Biol 13:4976–4985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafizi S, Dahlback B 2006 Gas6 and protein S. Vitamin K-dependent ligands for the Axl receptor tyrosine kinase subfamily. FEBS J 273:5231–5244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridell YW, Jin Y, Quilliam LA, Burchert A, McCloskey P, Spizz G, Varnum B, Der C, Liu ET 1996 Differential activation of the Ras/extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinase pathway is responsible for the biological consequences induced by the Axl receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol 16:135–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goruppi S, Ruaro E, Schneider C 1996 Gas6, the ligand of Axl tyrosine kinase receptor, has mitogenic and survival activities for serum starved NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Oncogene 12:471–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto AL, Weber JL, Lai C 2000 Expression of the receptor protein-tyrosine kinases Tyro-3, Axl, and mer in the developing rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 425:295–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto AL, Weber JL, Tracy S, Heeb MJ, Lai C 1999 Gas6, a ligand for the receptor protein-tyrosine kinase Tyro-3, is widely expressed in the central nervous system. Brain Res 816:646–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothlin CV, Ghosh S, Zuniga EI, Oldstone MB, Lemke G 2007 TAM receptors are pleiotropic inhibitors of the innate immune response. Cell 131:1124–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Gore M, Zhang Q, Camenisch T, Boast S, Casagranda F, Lai C, Skinner MK, Klein R, Matsushima GK, Earp HS, Goff SP, Lemke G 1999 Tyro-3 family receptors are essential regulators of mammalian spermatogenesis. Nature 398:723–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G, Lu Q 2003 Macrophage regulation by Tyro 3 family receptors. Curr Opin Immunol 15:31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Chen Y, Wang H, Wang H, Wu H, Lu Q, Han D 2008 Gas6 and the Tyro 3 receptor tyrosine kinase subfamily regulate the phagocytic function of Sertoli cells. Reproduction 135:77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Tang H, Chen Y, Wang H, Han D 2008 High incidence of distal vaginal atresia in mice lacking Tyro3 RTK subfamily. Mol Reprod Dev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MP, Linseman DA, Udo H, Xu M, Schaack JB, Varnum B, Kandel ER, Heidenreich KA, Wierman ME 2002 Novel mechanism for gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration involving Gas6/Ark signaling to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol 22:599–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Raitcheva D, Bless EP, Ackerman SL, Tobet S 2004 Netrin 1-mediated chemoattraction regulates the migratory pathway of LHRH neurons. Eur J Neurosci 19:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto AL, O'Dell S, Varnum B, Lai C 2007 Localization and signaling of the receptor protein tyrosine kinase Tyro3 in cortical and hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 150:319–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Porteous R, Pape JR, Mora JM, Hurst PR 2008 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron requirements for puberty, ovulation, and fertility. Endocrinology 149:597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WS, Smith MS, Hoffman GE 1990 Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons express Fos protein during the proestrous surge of luteinizing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:5163–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt ES, Brunetta PG, Seiler GR, Barney SA, Selles WD, Wooledge KH, King JC 1992 Subgroups of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone perikarya defined by computer analyses in the basal forebrain of intact female rats. Endocrinology 130:1030–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo-Scherrer A, de Frutos P, Aparicio C, Melis E, Savi P, Lupu F, Arnout J, Dewerchin M, Hoylaerts M, Herbert J, Collen D, Dahlback B, Carmeliet P 2001 Deficiency or inhibition of Gas6 causes platelet dysfunction and protects mice against thrombosis. Nat Med 7:215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo-Scherrer A, Burnier L, Flores N, Savi P, DeMol M, Schaeffer P, Herbert JM, Lemke G, Goff SP, Matsushima GK, Earp HS, Vesin C, Hoylaerts MF, Plaisance S, Collen D, Conway EM, Wehrle-Haller B, Carmeliet P 2005 Role of Gas6 receptors in platelet signaling during thrombus stabilization and implications for antithrombotic therapy. J Clin Invest 115:237–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW 1991 Migration of LHRH-immunoreactive neurons from the olfactory placode rationalizes olfacto-hormonal relationships. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 39:565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouis R, Hardelin JP, Levilliers J, Claverie JM, Compain S, Wunderle V, Millasseau P, Le Paslier D, Cohen D, Caterina D 1991 The candidate gene for the X-linked Kallmann syndrome encodes a protein related to adhesion molecules. Cell 67:423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi-Yanicostas N, de Castro F, Julliard AK, Perfettini I, Chedotal A, Petit C 2002 Anosmin-1, defective in the X-linked form of Kallmann syndrome, promotes axonal branch formation from olfactory bulb output neurons. Cell 109:217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hu Y, Cadman S, Bouloux P 2008 Diversity in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 regulation: learning from the investigation of Kallmann syndrome. J Neuroendocrinol 20:141–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitteloud N, Zhang C, Pignatelli D, Li JD, Raivio T, Cole LW, Plummer L, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Mellon PL, Zhou QY, Crowley Jr WF 2007 Loss-of-function mutation in the prokineticin 2 gene causes Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17447–17452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PR, Wray S 2000 Novel gene expressed in nasal region influences outgrowth of olfactory axons and migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons. Genes Dev 14:1824–1834 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bless EP, Westaway WA, Schwarting GA, Tobet SA 2000 Effects of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor manipulation on migrating gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through the entire migratory route in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology 141:1254–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bless EP, Walker HJ, Yu KW, Knoll JG, Moenter SM, Schwarting GA, Tobet SA 2005 Live view of gonadotropin-releasing hormone containing neuron migration. Endocrinology 146:463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heger S, Seney M, Bless E, Schwarting GA, Bilger M, Mungenast A, Ojeda SR, Tobet SA 2003 Overexpression of glutamic acid decarboxylase-67 (GAD-67) in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons disrupts migratory fate and female reproductive function in mice. Endocrinology 144:2566–2579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fueshko SM, Key S, Wray S 1998 GABA inhibits migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in embryonic olfactory explants. J Neurosci 18:2560–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Henion TR, Nugent JD, Caplan B, Tobet S 2006 Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 12) and chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 4 are required for migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to the forebrain. J Neurosci 26:6834–6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini P, Messina A, Wray S, Giampietro C, Crepaldi T, Carmeliet P, Fasolo A 2007 Hepatocyte growth factor acts as a motogen and guidance signal for gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone-1 neuronal migration. J Neurosci 27:431–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini P, Giampietro C, Fioretto M, Maggi R, Cariboni A, Perroteau I, Fasolo A 2002 Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor facilitates migration of GN-11 immortalized LHRH neurons. Endocrinology 143:3306–3315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitteloud N, Quinton R, Pearce S, Raivio T, Acierno J, Dwyer A, Plummer L, Hughes V, Seminara S, Cheng YZ, Li WP, Maccoll G, Eliseenkova AV, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA, Hayes FJ, Boepple P, Hall JE, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley W 2007 Digenic mutations account for variable phenotypes in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Invest 117:457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Kostek C, Bless EP, Ahmad N, Tobet SA 2001 Deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) regulates the migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons to the basal forebrain. J Neurosci 21:911–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]