Abstract

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD), including Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and related disorders such as Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND) are the most common form of developmental disability and birth defects in the western world. Early recognition and accurate diagnosis by mental health professionals remains a key issue. This article reviews history, mechanisms of alcohol exposure, epidemiology, diagnosis and management of FASD.

Overview of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders for Mental Health Professionals

In the 30 years since the term fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) was first used by Jones and Smith to describe a group of children, born to alcoholic mothers, who had growth retardation, characteristic facial features and central nervous system involvement, it is now recognized that prenatal alcohol exposure can cause a broad spectrum of developmental, emotional, behavioural and social deficits extending far beyond the original case definition (Jones et al, 1973).

Fetal alcohol syndrome and related conditions are the most common and completely preventable form of developmental disability and birth defects in the western world. The spectrum of deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure is now being referred to as “Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders” or FASD (Streissguth et al, 2000). This new umbrella term encompasses other conditions associated with fetal alcohol exposure such as fetal alcohol effects (FAE), partial FAS (PFAS), alcohol related birth defects (ARBD) and alcohol related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND). All of these terms refer to situations where the patient has some but not all the findings of FAS and a history of alcohol exposure during gestation. The estimated incidence of FAS is between 0.5 and 3 per 1,000 live births. The estimated incidence of conditions within the FASD category is 10 per 1000 live births (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Preface, 1999). Despite increased public awareness of FASD, early recognition and accurate diagnosis by mental health professionals continues to be a significant issue (Streissguth et al, 2000; Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Preface 1999). Despite increased public awarness of FASD, early recognition and accurate diagnosis by mental health professionals continues to be a significant issue (Streissguth et al, 2000; Alberta clinical practice Guideliness, preface 1999). The Alberta Medical Association Clinical Practice Guidelines, reprinted in this journal edition, represent one initiative to provide a synthesis of knowledge and best practices for medical professionals. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of FASD.

History of FASD

Recognition that alcohol can have harmful effects on pregnancy and child outcomes is not a new finding. Lemoine and colleagues (Lemoine et al, 1968) in 1968 reported changes in a group of 127 children born to alcoholic mothers who had the same constellation of symptoms reported by Jones and Smith (Jones et al, 1973). Streissguth and colleagues describe case reports in the literature from as early as 1726 (Streissguth et al, 2000). However, the naming of the syndrome in 1973 focused new attention on alcohol use and abuse as a serious public health issue and encouraged research into the basic mechanisms of prenatal alcohol exposure and its long-term consequences.

Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of FAS

Physicians are frequently asked what is the safe “lower limit” for alcohol consumption during pregnancy. The absolute amount of alcohol that will not cause damage to the developing fetus is not known. What is known is that the risk of FASD increases dramatically once the level of “frequent drinking,” 6 to 8 drinks per occasion, is reached. We also know that at even lower levels, 1 to 3 drinks per occasion, long term changes in attention, cognition and learning can occur (May, 1995; Olson et al, 1998). Binge drinking during pregnancy, even when infrequent, can cause damage due to high peak alcohol concentration and is itself a drinking pattern associated with an increased risk of FASD. The prevalence of maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy has increased from 12.4% to 16.3% between 1991 and 1995. Moreover, frequent drinking during pregnancy, defined as 7 or more drinks per week, has increased during the same time period from 0.8% to 3.5% (Ebrahim et al, 1998) In the face of this increasing pattern of maternal alcohol consumption, it is imperative that all women be screened for alcohol use. Appearance, culture or socioeconomic status cannot identify a pregnant woman who consumes alcohol. Hicks and colleagues review key aspects of screening for alcohol use during pregnancy in this journal edition. Some key points for assessing risk during a prenatal alcohol history include:

Presence of a heavy drinking partner – most women drink with their partners;

Past history of sexual or physical abuse – a study of 80 birth mothers of children with FAS revealed that 95% were physically or sexually abused during their lifetime (Astley et al, 2000; Astley et al, 2000);

Presence of mental health disorders – in the same study of 80 birth mothers 96% had 1 to 10 mental health disorders the most prevalent being post traumatic stress disorder (77%) and phobia (44%),

Polysubstance abuse profile; and

Social isolation and lack of social support (Astley et al, 2000; Astley et al, 2000).

Interventions should be tailored to deal not only with the alcohol abuse but also the other risk factors identified. In most provinces there is no waiting period for pregnant women in need of addictions treatment. Studies indicate that a supportive counseling and/or case management approach can result in 60 to 80 percent of pregnant women reducing their alcohol intake before the third trimester and 35 to 50 percent stopping heavy drinking (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Recommendations, 1999).

Once a diagnosis of FASD is made, intensive case management that addresses the medical and social needs of the biological mother and her family must be offered to prevent the occurrence of future affected children. The risk of recurrence of FASD in families with one affected child is 77% (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Recommendations, 1999). Use of the lay advocate approach, first developed in Seattle by Streissguth and Grant, that supports the mother and facilitates access to resources has been shown to be effective in maintaining abstinence and promoting contraceptive use in high-risk women (Streissguth, 1997). Similar programs are now running in many major centres in Canada (Roberts et al, 2000).

Spectrum of Alcohol Damage and Alcohol Related Effects

Alcohol is a known teratogen that can cause a spectrum of damage and disrupt fetal development in all three trimesters. Alcohol and its metabolites interfere with DNA synthesis, cell division as well as cell migration and development. Exposure in the first trimester affects organ development and craniofacial development. Structural brain abnormalities are most common followed by cardiac abnormalities, especially septal defects. The whole range of alcohol related birth defects (ARBD) is presented in Table 1 (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Preface, 1999; Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Diagnosis, 1999; Stratton et al, 1996). Exposure in the second trimester leads to an increased rate of spontaneous abortions. Exposure to alcohol in the third trimester has a more severe effect on birth weight and length. Prenatal exposure to alcohol disrupts fetal brain development at any point in gestation.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol-Related Effects

| 1. Alcohol-related birth defects |

| Cardiac: Atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, aberrant great vessels, Tetralogy of Fallot. |

| Skeletal: Hypoplastic nails, shortened fifth digit, radioulnar synostosis, joint contractures, camptodactyly, clinodactyly, pectus excavatum and carinatum, Klippel-Feil syndrome, hemivertebrae, scoliosis. |

| Renal: Aplastic, dysplastic, hypoplastic kidneys, horseshoe kidneys, ureteral duplications, hydronephrosis. |

| Ocular: Strabismus, refractive problems secondary to small globes, retinal vascular anomalies. |

| Auditory: Conductive hearing loss, neurosensory hearing loss. |

| Other: Virtually every malformation has been described in some patient with FAS. The etiologic specificity of most of these anomalies to alcohol teratogenesis remains uncertain. |

| 2. Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder |

| Presence of A and/or B. |

|

| Adapted from Stratton K, How C, Battaglia: FAS Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention and Treatment, Washington, D.C. Naional Academy Press, 1996 |

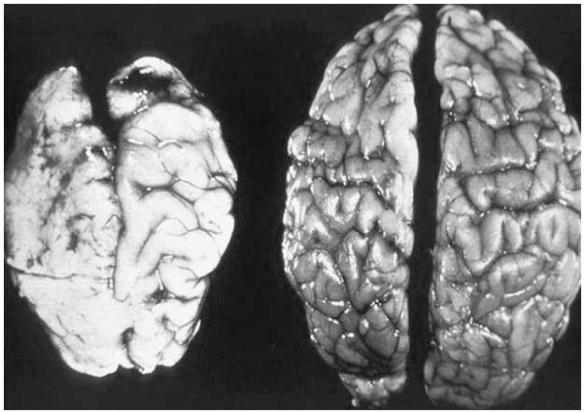

Alcohol related brain deficits can manifest as either structural changes such as microcephaly, agenesis of the corpus callosum or cerebellar hypoplasia; or functional deficits affecting behaviour and cognition. Gibbard and colleagues in this journal edition will fully review the range and consequences of these brain deficits.

The Institute of Medicine criteria summarized in Table 1 lists the various criteria associated with alcohol related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND).

FAS Diagnostic Categories

Since FAS was first defined in 1973 researchers and clinicians have struggled to find consistent terminology to describe the spectrum of effects and the individual criteria that should be included in the diagnosis. In 1996, the US institute of Medicine published new diagnostic categories that are summarized in Table 2 (Jones et al, 1973; Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Diagnosis, 1999; Stratton et al, 1996).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for FAS

1. FAS with confirmed maternal alcohol exposure

|

| 2. FAS without confirmed maternal alcohol exposure |

| B, C and D above |

| 3. Partial FAS with confirmed maternal alcohol exposure |

|

| 1. A pattern of excessive intake characterized by substantial, regular intake or heavy episodic drinking. Evidence of this pattern may include frequent episodes of intoxication, development of tolerance or withdrawal, social problems related to drinking, legal problems related to drinking, engaging in physically hazardous behavior while drinking, or alcohol related medical problems, such as hepatic disease. |

| Adapted from Stratton K, How C, Battaglia: FAS Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention and Treatment, Washington, D.C., National Academy Press, 1996 and Jones KL, Smith DW: Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet 1973; 2(7836): 999–1001. |

The term FAS without confirmed alcohol exposure is used when children have all the growth, facial and CNS characteristics, but there is no way to accurately verify the mother’s use of alcohol.

The term partial FAS is applied to the patient with a confirmed history of prenatal alcohol exposure who has some but not all the characteristics of FAS. Partial does not mean that the condition is less severe than FAS. Many patients diagnosed as partial FAS would have been designated as Fetal Alcohol Effect or FAE under previous informal classification systems. The use of the term FAE has been discouraged by its originator Dr. Sterling Clarren, since it is non-specific and encompasses a broad range of conditions that have varying severity and outcomes (Aase et al, 1995). A common misconception is that FAE is a less severe form of FAS. Although the patient designated as FAE may not have all the physical abnormalities of FAS, the cognitive and behavioural impairments and hence life long disabilities are similar in severity.

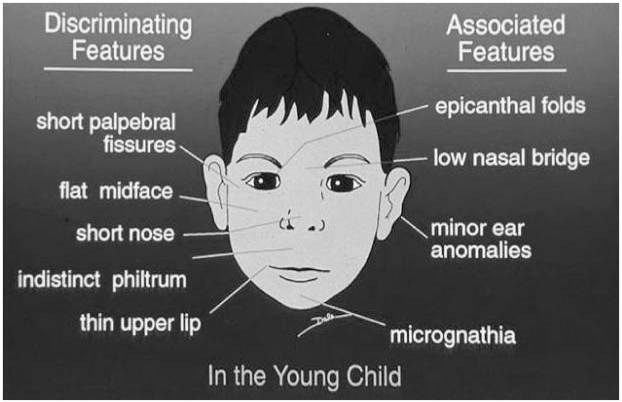

Primary Features and Disabilities of FAS - Growth, Face and Brain

The growth pattern characteristic of FAS usually presents in the prenatal period and persists as a consistent impairment over time. In contrast, growth deficiency due to postnatal influences will likely present as periodic fluctuations in the growth curve. The most consistent features of the FAS facial phenotype include small palpebral fissures (reflecting small eyes), a smooth philtrum and a thin upper lip. Criteria and norms have now been established by Astley and Clarren that allow for more accurate case definitions (Astley et al, 2000). A manual and CD-ROM have been developed to provide clinicians with specific information on how to examine and measure the facial features (Astley et al, 2000; Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Tutor, 1999).

Additional practice points include the following:

The likelihood of an FAS diagnosis is greatest when the three features of thin upper lip, smooth philtrum and small palpebral fissures are present;

Small eyes persist into adolescence and adulthood and may be a reliable physical marker in older individuals;

Facial features and growth delay diminish in adolescence and hence it is important to obtain past facial photographs and growth records; and

If there are no facial features, but there is a definitive history of prenatal alcohol exposure, other conditions within the alcohol related spectrum need to be explored.

Figure 1 shows the major and associated features of FAS. Other conditions that have similar facial characteristics include Fragile X Syndrome, Velocardiofacial Syndrome and Fetal Dilantin Syndrome.

Figure 1.

Facial Features of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the brain manifestations of prenatal alcohol exposure. This photograph has been used widely in FAS public awareness campaigns and compares the brain of a child who died at birth due to severe FAS to that of a normal newborn. This is an extreme example of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and would not be a typical finding.

Figure 2.

Brain Manifestations of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

Severity of brain dysfunction can be placed on a continuum from subtle neurobehavioral deficits to obvious structural abnormalities. The primary functional brain disabilities of FAS can be organized according to a mnemonic “ALARM” (Loock, 2001).

Adaptive Functioning

Language/Learning

Attention

Reasoning

Memory

The level of adaptive functioning and ability to live independently in individuals with FASD is often less than half the patient’s chronological age. Less than 10% of adults with FAS live independently due to impairments in life and social skills, despite having low average or average intellectual abilities (Olson et al, 1998). Language deficits result from a global impairment in executive functioning due to prenatal alcohol exposure. The understanding of complex language and figures of speech is markedly deficient (Coggins et al, 1998).Hence the use of language as a social or behavioural mediator is poor and further compromises the adaptive functioning and learning potential of the affected individual (Streissguth et al, 1991). The majority of children with FASD have attention difficulties but differ from other types of ADHD in having an earlier onset, more complex comorbidities and a different response profile to psychostimulants (Streissguth et al, 2000). Reasoning and memory deficits are also related to basic impairments in executive functioning of the brain and become more noticeable when the FAS affected person reaches school age. Patients with FAS are often slow to learn new skills and do not learn from past experiences. IQ testing may not reveal the reasoning and memory deficits seen in FASD and more specialized neuropsychological testing is often required (Olson et al, 1998).

Each component of the FAS diagnosis can range in severity according to the patient’s age, environmental variables and the quantity and quality of prenatal alcohol exposure. Hence it is easy to see why no two individuals with FAS will present with the same constellation of abnormalities and disabilities. In response to these limitations Astley and Clarren have developed a new diagnostic system where growth, facial phenotype, CNS dysfunction and alcohol exposure all vary along separate continua (Astley et al, 2000).

The “4-Digit Diagnostic Grid” allows the features of growth, face, brain and alcohol use to be ranked independently on a 4 point Likert scale, with 1 reflecting complete absence of FAS features and 4 reflecting strong presence of the FAS features. Many diagnostic teams in Canada and the United States are now using this approach.

Secondary Disabilities, Co-Existing Conditions and Protective Factors

The secondary disabilities of FAS arise after birth as a result of the neurological deficits and come at a high cost to the individual, their family and society.

Common secondary disabilities include:

Mental health disorders – depression and suicidal ideation

Disrupted school and employment experience;

Trouble with the law;

Inappropriate sexual behavior and involvement in the sex trade; and

Addictions (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Diagnosis, 1999).

FASD usually occurs within a constellation of co-existing prenatal and postnatal social and medical comorbidities. Coexisting conditions that are more commonly associated with FASD are attachment disorders as well as sequelae of abuse and neglect such as shaken baby syndrome.

The impact of these secondary conditions may be reduced significantly by the following protective factors:

Early diagnosis;

Appropriate interventions for primary and secondary disabilities;and

Placement in a stable and nurturing environment that is non-abusive (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Diagnosis, 1999).

However, the mental health disorders that present in patients with FASD do not appear to be impacted significantly by the above protective factors (Streissguth, 1997).

Long-Term Impact of FASD

Streissguth and O’Malley have summarized the studies looking at the long-term mental disorders and maladaptive behaviours associated with FASD (Streissguth et al, 2000). Streissguth studied 61 adolescents and adults with a FAS/FAE diagnosis and the follow-up showed a wide range of mental and behavioural symptoms. The most common symptoms included: attention difficulties, social withdrawal, impulsive behaviour, dependent behaviour, teasing and bullying behaviour, anxiety, stubborn or sullen mood, lying, cheating and stealing. The authors also report on studies from Europe including Spohr (1996) and Steinhausen (1996) that reveal a similar range of difficulties in the spheres of attention deficits, impulse control, aggression and other deficits in executive functioning. Steinhausen, a psychiatrist from Berlin, reported that 63% of his patients had psychiatric disorders that were long-term and the majority of these patients required intensive therapeutic management. Finally, Lemoine and colleagues were able to identify 105 of the 127 patients of alcoholic mothers from their original study in 1968 and they concluded that mental problems were the most serious sequelae of FAS in adulthood (Lemoine et al, 1992).

Management

FASD is a clinical diagnosis that can have varying physical and developmental manifestations across the lifespan. A multidisciplinary team approach is recognized as a best practice standard for making the diagnosis and planning interventions. Psychiatric input into this multidisciplinary team is critical to making an accurate diagnosis of FASD and associated psychiatric comorbidities, and also to the effective management of secondary mental health disabilities

Management in the primary care setting begins with screening for the key manifestations of FASD and facilitating an early and accurate diagnosis by a multidisciplinary team that can address primary and secondary disabilities. It is important to recall that FASD is a diagnosis for two. Biological parents should be identified and supported so that future pregnancies are not alcohol affected.

Additional management strategies include:

Support to caregivers and educators through the provision of resources and information (see Internet resources; Graefe, 1998; FAS/FAE Technical Working Group, 2001);

Routine screening of patients with FASD for the primary brain disabilities – ALARM and advocacy for early and intensive intervention;

Identify advocates for the affected individual who can act as an “external brain” or protector / custodian;

If medications are necessary provide close follow-up, monitor for side effects and begin at a lower starting dose;

Regular surveillance for onset of secondary disabilities and aggressive intervention when they occur; and

Long-term, structured supervised residential, educational and vocational supports (Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines, Diagnosis, 1999).

In summary, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals can play a key role in the effective prevention, diagnosis and management of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. The articles in the remainder of this journal edition are devoted to the topic of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and hopefully will provide further insight into current practices, knowledge, screening and the mental health disabilities associated with this condition.

Suggested additional reading is noted in the References with an a.sterix (*).

Abbreviations

- FAS

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- FASD

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- FAE

Fetal Alcohol Effect

- PFAS

Partial Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- ARBD

Alcohol Related Birth Defects

- ARND

Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder

- ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

References

- Aase JM, Jones KL, Clarren SK. Do We Need the Term “FAE”? Pediatrics. 1995;90(3):428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines. Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) Alberta Partnership on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alberta Medical Association, The Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines Program; June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- *.Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines. Preface to the Prevention & Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) Alberta Partnership on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alberta Medical Association, The Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines Program; June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- *.Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines. Recommendations on Prevention of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) Alberta Partnership on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alberta Medical Association, The Alberta Clinical Practice Guidelines Program; June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- *.Astley S, Clarren SK. The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code. University of Washington; 1999. Diagnostic Guide for FAS and Related Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- *.Astley SJ, Bailey D, Talbot C, Clarren SK. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) primary prevention through FAS diagnosis: I. A comprehensive profile of 80 birth mothers of children with FAS. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2000;35:509–512. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Astley SJ, Bailey D, Talbot C, Clarren SK. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) primary prevention through FAS diagnosis: II. Identification of high-risk mothers through the diagnosis of the children. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2000;35:499–509. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Astley SJ, Clarren SK. Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol-exposed individuals: introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2000;35:400–414. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins TE, Friet T, Morgan T. Analyzing narrative production in older school-age children and adolescents with fetal alcohol syndrome: an experimental tool for clinical applications. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 1998;12(3):221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim S, Floyd R, Bennet E. Alcohol consumption by pregnant women in the United States during 1988–1995. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAS/FAE Technical Working Group. It Takes a Community Framework for the First Nations and Inuit Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Effects Initiative. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Tutor. Medical Training Software. Interactive software that assists in the screening and diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome. FAS Diagnostic and Prevention Network, Department of Laboratory Medicine, and the Office of Continuing Medical Education; University of Washington, Seattle, WA. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe Sara. FAS – Parenting Children Affected by Fetal Alcohol Syndrome – A Guide for Daily Living. 1998. The Society of Special Needs Adoptive Parents (SNAP) [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;2(7836):999–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine P, Lemoine P. Avenir des enfants de mères alcooliques (étude de 105 cas retrouves a l age adulte) et quelques constatations d’intérêt prophylactique. Ann Pediatr. 1992;39:226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine P, Harouusseau H, Borteyru JP, et al. Les enfants de parents alcooliques: Anomalies observées, a propos de 127 cas. Ouest Med. 1968;21:476–482. [Google Scholar]

- Loock, Christine. Personal communication, 2001.

- May P. A multiple-level, comprehensive approach to the prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and other alcohol related birth defects (ARBD) The International Journal of Addictions. 1995;30(12):1549–1602. doi: 10.3109/10826089509104417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson HC, Feldman JJ, Steissguth AP, Sampson PD. Clinical neuropsychological deficits in adolescents with fetal alcohol syndrome: clinical findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1998–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Nanson JL. Health Canada. 2000. Best Practices: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome/Fetal Alcohol Effects and the Effects of Other Substance Use in Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Spohr HL. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Adolescence: Long-term perspective of children diagnosed in infancy. In: Spohr HL, Steinhausen HC, editors. Alcohol, Pregnancy and the Developing Child. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention and treatment. Washington: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC. Psychopathology and cognitive functioning in children with fetal alcohol syndrome. In: Spohr HL, Steinhausen HC, editors. Alcohol, Pregnancy and the Developing Child. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, O’Malley K. Neuropsychiatric Implications and Long-term Consequences of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2000 Jul;5(3):177–190. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2000.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Aase JM, Clarren SK, et al. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Adolescents and Adults. JAMA. 1991;265:1961–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Streissguth AP. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: a guide for families and communities. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Publishing Co.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- Alberta Medical Association. Clinical Practice Guidelines. http//www.albertadoctors.org.

- Alcohol Related Birth Injury Site (ARBI) http://www.arbi.org/index.html.

- BC FAS Resource Society. Community Action Guide for the Prevention of FAS and A Layman’s Guide to FAS. http://www.mcf.gov.bc.ca/child.protection/fasfae.index.htm.

- BC Ministry of Education. Teaching Children with FAS. http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/specialed/fas/contents.htm.

- FAS/FAE Information Service. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. http://www.ccsa.ca/fasgen.htm.

- Health Canada. http://www.healthcanada.ca/fas.

- Seattle University of Washington FAS Diagnostic and Prevention Website. http://depts.wash.edu/fasdpn.