Abstract

Obesity is associated with an array of health problems in adult and pediatric populations. Understanding the pathogenesis of obesity and its metabolic sequelae has advanced rapidly over the past decades. Adipose tissue represents an active endocrine organ that, in addition to regulating fat mass and nutrient homeostasis, releases a large number of bioactive mediators (adipokines) that signal to organs of metabolic importance including brain, liver, skeletal muscle, and the immune system—thereby modulating hemostasis, blood pressure, lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. In the present review, we summarize current data on the effect of the adipose tissue-derived hormones adiponectin, chemerin, leptin, omentin, resistin, retinol binding protein 4, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, vaspin, and visfatin on insulin resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Adipose tissue is composed of adipocytes embedded in a loose connective tissue meshwork containing adipocyte precursors, fibroblasts, immune cells, and various other cell types. Adipose tissue was traditionally considered an energy storage depot with few interesting attributes. Due to the dramatic rise in obesity and its metabolic sequelae during the past decades, adipose tissue gained tremendous scientific interest. It is now regarded as an active endocrine organ that, in addition to regulating fat mass and nutrient homeostasis, releases a large number of bioactive mediators (adipokines) modulating hemostasis, blood pressure, lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Table 1 summarizes the adipokines discussed in this review article, the interplay between adipokines, and their effects on glucose homeostasis.

Table 1.

Adipokines, adipokine interplay and the effects on glucose homeostasisa

| Adipokine | Receptor | Effects on other adipokines | Metabolic function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | AdipoR1, AdipoR2, T-cadherin | Suppression of TNF-α and IL-6 expression | Suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis |

| Stimulation of fatty acid oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle | |||

| Stimulation of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle | |||

| Stimulation of insulin secretion | |||

| Modulation of food intake and energy expenditure | |||

| Chemerin | CMKLR1 | Suppression of TNF-α and IL-6 expression | Enhancement of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and IRS-1 phosphorylation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes |

| Stimulation of adiponectin expression | |||

| Leptin | LR isoforms a–eb | Stimulation of TNF-α and IL-6 expression | Repression of food intake |

| Suppression of resistin and retinol binding protein 4 expression | Promotion of energy expenditure | ||

| Stimulation of adiponectin expression | Stimulation of fatty acid oxidation in liver, pancreas and skeletal muscle | ||

| Modulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis | |||

| Modulation of pancreatic β-cell function | |||

| Omentin | Unknown | Unknown | Enhancement of insulin-stimulated glucose transport and Akt phosphorylation in human adipocytes |

| Resistin | Unknown | Stimulation of TNF-α and IL-6 expression | Induction of insulin resistance in mice |

| Lack of a clear function in glucose metabolism in humans | |||

| Retinol binding protein 4 | unknown (RAR, RXR, cell surface receptors?) | Unknown | Stimulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice |

| Impairment of skeletal muscle insulin signaling in mice | |||

| Uncertain effect on insulin resistance in humans | |||

| Tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-6 | TNFR, IL-6R/gp130 | Stimulation of leptin, resistin, and visfatin/PBEF/Nampt expression | Modulation of hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin signaling |

| Suppression of adiponectin and retinol binding protein 4 expression | |||

| Vaspin | —c | Suppression of leptin, resistin, and TNF-α expression | Improvement of insulin sensitivity in mice |

| Stimulation of adiponectin expression | Uncertain effect on insulin sensitivity in humans | ||

| Visfatin/PBEF/Nampt | —d | Stimulation of TNF-α and IL-6 expression | Stimulation of insulin secretion in mice |

| Uncertain effect on insulin resistance in rodents and humans |

Abbreviations in table: AdipoR1, adiponectin receptor 1; AdipoR2, adiponectin receptor 2; CMKLR1, chemokine like receptor-1; IL-6R, interleukin-6 receptor; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; LR, leptin receptor; Nampt, nicotinamide phophoribosyltransferase; PBEF, pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; RXR retinoic acid-X receptor; TNFR, Tumor necrosis factor-α receptor; vaspin, visceral adipose tissue-derived serine protease inhibitor.

LRb is restricted to the hypothalamus, brainstem and key regions of the brain which control feeding, energy balance and glucose metabolism.

Effects likely to be mediated through inhibition of a yet-unknown protease.

Effects mediated through nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthetic activity.

ADIPONECTIN

Adiponectin expression occurs from an intermediate stage of adipogenesis onwards (1,2), and represents the most abundant protein secreted by adipose tissue. Unlike most other adipokines, plasma adiponectin levels were reduced in animal models of obesity and insulin resistance (2,3). Administration of recombinant adiponectin to rodents resulted in increased glucose uptake and fat oxidation in muscle, reduced hepatic glucose production, and improved whole-body insulin sensitivity (4–6). Adiponectin transgenic mice showed partial amelioration of insulin resistance and diabetes (7) and suppression of endogenous glucose production (8). In contrast, adiponectin-deficient mice exhibited insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (9–11). In addition to its insulin-sensitizing effects, adiponectin may alter glucose metabolism through stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion in vivo (12). Apart from its peripheral actions, adiponectin was shown to modulate food intake and energy expenditure during fasting (increased food intake and reduced energy expenditure) and refeeding (opposite effects) through its effects in the central nervous system (13).

In humans, plasma adiponectin levels were correlated negatively with adiposity (14–17), insulin resistance (16,18,19), type 2 diabetes (16,20), and metabolic syndrome (21–23), yet positively correlated with markers of insulin sensitivity in frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance testing (17,24,25) and clamp studies (15,19). Prospective and longitudinal studies indicated that lower adiponectin levels were associated with a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes (26–33). Adiponectin single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been associated variably with increased body mass index (BMI), insulin resistance-related traits, and type 2 diabetes (34). However, in a systematic meta-analysis of all published data on adiponectin SNPs, only the +276G→ T variant was a strong determinant of insulin resistance with minor allele homozygotes having a lower homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance index than carriers of other genotypes. No consistent effect on BMI or risk of type 2 diabetes was observed (34).

Adiponectin circulates in plasma as a low-molecular weight trimer, a middle-molecular weight hexamer, and high-molecular weight (HMW) 12- to 18-mer, and these forms were postulated to differ in biologic activity (35,36). HMW adiponectin was proposed to be the biologically active form of the hormone (37), and, although not unchallenged (38), was shown to be superior to total adiponectin in predicting insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome trait cluster (39–41). Adiponectin expression and secretion was demonstrated to be upregulated by thiazolidinediones (TZDs) (42–44), and HMW adiponectin is the predominant form of adiponectin increased by TZDs (37).

Adiponectin’s effects on glucose metabolism are mediated through two distinct receptors termed adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1) and adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2). AdipoR1 is expressed ubiquitously, whereas AdipoR2 is expressed most abundantly in the liver (45). Similar to adiponectin, expression of both receptors was decreased in mouse models of obesity and insulin resistance (46,47). Yamauchi et al. (47) reported that liver-specific adenoviral expression of AdipoR1 in leptin-receptor deficient db/db mice resulted in activation of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), leading to reduced expression of genes encoding hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes such as glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, and of genes encoding molecules involved in lipogenesis, such as sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c. Hepatic expression of AdipoR2 increased expression of genes involved in hepatic glucose uptake such as glucokinase, and of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α) and its target genes such as acyl-CoA oxidase and uncoupling protein 2. Activation of AMPK reduced endogenous hepatic glucose production, while expression of both receptors increased fatty acid oxidation, decreased hepatic triglyceride content and improved insulin resistance. Conversely, targeted disruption of AdipoR1 resulted in the abrogation of adiponectin-induced AMPK activation, and in increased endogenous glucose production and insulin resistance. Knockout of AdipoR2 caused decreased activity of PPAR-α signaling pathways and insulin resistance. Simultaneous disruption of both AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 abolished adiponectin binding and actions, resulting in increased glucose intolerance and insulin resistance compared with the single knockout models (47). The role of T-cadherin, another putative adiponectin receptor (48), in adiponectin signaling appeared to be minor since, in contrast to control mice, administration of adiponectin to AdipoR1/R2 double knockout mice did not improve plasma glucose levels (47). The impact of AdipoR1 and AipoR2 on glucose metabolism in rodents has been examined by two more studies with, in part, conflicting results. Bjursell et al. (49) reported that AdipoR1 knockout mice showed increased adiposity associated with decreased glucose tolerance, reduced spontaneous locomotor activity, and decreased energy expenditure. Unexpectedly, however, AdipoR2 deficient mice were lean and resistant to high fat diet-induced obesity associated with improved glucose tolerance and increased spontaneous locomotor activity and energy expenditure. Consistent with these data, Liu et al. (50) demonstrated that disruption of AdipoR2 diminished high fat-induced insulin resistance and reduced plasma glucose levels in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. However, glucose homeostasis in these animals on long-term high fat diet deteriorated because of failure of pancreatic β-cells to compensate for the moderate insulin resistance.

In humans, data regarding a possible association of adiponectin receptor expression in adipose tissue or skeletal muscle and obesity or insulin resistance were highly divergent and dependent on the population studied (51–59). Furthermore, although polymorphisms in both adiponectin receptor genes have been found to be associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (34,60), these associations have not been replicated widely across populations. Thus, the number of studies available to date is still too small to draw firm conclusions on the role of variability in AdipoR1 and/or AdipoR2 expression in predicting insulin resistance and related disorders.

In summary, adiponectin is an abundantly expressed adipokine that exerts a potent insulin-sensitizing effect through binding to its receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, leading to activation of AMPK, PPAR-α, and presumably other yet-unknown signaling pathways. In obesity-linked insulin resistance, both adiponectin and adiponectin receptors are downregulated. Upregulation of adiponectin/adiponectin receptors or enhancing adiponectin receptor function may represent an interesting therapeutic strategy for obesity-linked insulin resistance.

CHEMERIN

Chemerin (RARRES2 or TIG2) is a recently discovered chemokine (61) highly expressed in liver and white adipose tissue (62,63). It exerts potent antiinflammatory effects on activated macrophages expressing the chemerin receptor CMKLR1 (chemokine-like receptor-1) in a cysteine protease-dependent manner (64). Furthermore, chemerin is crucial for normal adipocyte differentiation and modulates the expression of adipocyte genes involved in glucose and lipid homeostasis, such as glucose transporter-4, fatty acid synthase, and adiponectin via its own receptor (62,63,65). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, chemerin was reported to enhance insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) tyrosine phosphorylation, suggesting that chemerin may increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue (66). Conflicting data exist regarding the association of chemerin with obesity and diabetes in rodents. Chemerin expression was shown to be decreased in adipose tissue of db/db mice compared with controls (66). In contrast, chemerin expression was significantly higher in adipose tissue of impaired glucose tolerant and diabetic Psammomys obesus compared with normal glucose tolerant sand rats (62). In humans, chemerin levels did not differ significantly between subjects with type 2 diabetes and normal controls. However, in normal glucose tolerant subjects, chemerin levels were associated significantly with BMI, triglycerides, and blood pressure (62). Further studies are needed to determine the physiological role of chemerin in glucose metabolism, and to identify chemerin’s target tissues as well as relevant signal transduction pathways.

LEPTIN

Since its identification in 1994, leptin has attracted much attention as one of the most important signals for the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis (67–69). Hypothalamic as well as brain stem nuclei play a critical role in integrating the information on absorbed food, on the amount of energy stored in the form of fat and on blood glucose levels to regulate feeding, energy storage, or expenditure. Leptin receptor activation at these sites leads to repression of orexigenic pathways (for example, those involving neuropeptide Y [NPY] and agouti-related peptide [AgRP]) and induction of anorexigenic pathways (such as those involving pro-opiomelanocortin [POMC] and cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript [CART]) via Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) and IRS/phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) signaling (70). Although changes in food intake and total body fat clearly can affect insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, several observations suggested that leptin regulation of glucose homeostasis occurs independently of its effects on food intake through central and peripheral mechanisms. Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC)-specific expression of leptin receptor in leptin receptor-deficient mice resulted in a modest reduction of food intake and body fat mass, yet normalized blood glucose and insulin levels (71). ARC-specific restoration of leptin receptor in obese, leptin receptor-deficient Koletsky rats markedly improved insulin sensitivity via a mechanism that was not dependent on reduced food intake, but was attenuated by intraventricular infusion of a PI3K inhibitor (72). ARC-directed expression of a constitutively active mutant of protein kinase B, an enzyme activated by PI3K, mimicked the insulin-sensitizing effect of restored hypothalamic leptin signaling in these animals. In contrast, mice with a mutant leptin receptor that cannot signal via the JAK-STAT pathway, yet otherwise functions normally, developed severe hyperphagia and obesity, but unlike leptin receptor-deficient mice, exhibited only mild disturbances of glucose homeostasis that can be prevented by caloric restriction (73). These results suggested that although leptin receptor-mediated JAK-STAT signaling is essential for regulation of food intake and body weight, leptin-stimulated PI3K signaling appears to be important for regulation of glucose metabolism. Leptin also limits accumulation of triglycerides in liver and skeletal muscle through a combination of direct activation of AMPK and indirect actions mediated through central neural pathways, thereby improving insulin sensitivity (74,75). Furthermore, leptin modulates pancreatic β-cells function through direct actions (76,77) and indirectly through central neural pathways (78,79). Leptin was shown to inhibit insulin secretion in lean animals. As body weight increased, leptin signaling protected the β-cell from adverse effects of overnutrition such as lipid accumulation, thus improving β-cell function (77). Insulin stimulates both leptin biosynthesis and secretion from adipose tissue establishing a classic endocrine adipo-insular feedback loop; the so-called “adipo-insular axis” (80).

The concept of “leptin resistance” was introduced when increased adipose leptin production was observed in the majority of obese individuals without adequate leptin-mediated end-organ response (81). Leptin improves glucose homeostasis in humans with lipodystrophy or congenital leptin deficiency (82,83). However, results in humans with ‘typical’ obesity were disappointing in this regard (84). Studies in obese rodents suggested that leptin resistance is associated with impairment of leptin transport across the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), reduction of leptin-mediated JAK-STAT signaling, and induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3) (81,85). Attenuation of leptin sensitivity in the brain leads to excess triglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, as well as muscle, liver, and pancreas, resulting in impaired insulin sensitivity and secretion (86). The concept of “leptin resistance” has been challenged recently by an alternate concept of “hypothalamic leptin insufficiency.” The major tenet of this postulation is that BBB restricts the blood-to-brain entry of leptin in response to hyperleptinemia resulting in leptin insufficiency at multiple target sites in the brain (87).

In summary, leptin serves as a major ‘adipostat’ by repressing food intake and promoting energy expenditure. Independent of these effects, leptin improves peripheral (hepatic and skeletal muscle) insulin sensitivity and modulates pancreatic β-cell function. In the majority of cases of obesity, despite both an intact leptin receptor and high circulating leptin levels, leptin fails to induce weight loss. This diminished response to the anorexigenic and insulin-sensitizing effects of leptin is called “leptin resistance.”

OMENTIN

Omentin is a fat depot-specific secretory protein synthesized by visceral stromal vascular cells, but not adipocytes. Omentin enhanced insulin-stimulated glucose transport and Akt phosphorylation in human subcutaneous and visceral adipocytes, suggesting that omentin may improve insulin sensitivity (88). Plasma omentin-1 levels, the major circulating isoform in human plasma, were correlated inversely with obesity and insulin resistance as determined by homeostasis model assessment yet correlated positively with adiponectin and HDL levels (89). Administration of glucose and insulin to human omental adipose tissue explants resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of omentin-1 expression. Furthermore, prolonged insulin-glucose infusion in healthy individuals resulted in significantly decreased plasma omentin-1 levels (90). The physiological role of omentin in glucose metabolism, omentin’s target tissues, a receptor, or relevant signal transduction pathways still need to be determined.

RESISTIN

Resistin, a member of the resistin-like molecule (RELM) family of cysteine-rich proteins, has a controversial history regarding its role in the pathogenesis of obesity-mediated insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Resistin was discovered in 2001 as a TZD-downregulated gene in mouse adipocytes (91). In rodents, circulating levels of resistin were increased in obesity (92), and both gain- (91,93–96) and loss-of-function studies (91,97–99) demonstrated a role for resistin in mediating hepatic or skeletal muscle (depending on the animal model) insulin resistance (94,95,97,98). There is considerable controversy about the role of resistin in humans. Human resistin is produced and secreted mainly by peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (100). Human studies over the past years reported contradictory findings with regards to a physiological role for resistin in glucose metabolism. Several groups suggested resistin levels and SNPs to be associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (19,101–106). However, other groups failed to identify changes in resistin levels or SNPs in these conditions (107–114). Although a clear function for resistin in glucose metabolism in humans is still lacking, data indicate that resistin has a role in inflammatory processes. The expression of resistin in human peripheral-blood mononuclear cells is upregulated by the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α(TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (115). Conversely, resistin induced the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in white adipose tissue and in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (116–118). Plasma resistin levels were reported to be associated with many inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (119), soluble TNF-α receptor-2, IL-6, and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (120) in several pathophysiological conditions. Resistin was shown to be associated with disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (121), to correlate with severity of disease in severe sepsis and septic shock (122), and to be associated with coronary artery disease (120). Furthermore, resistin may be involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (117). Considering the crosstalk between inflammatory pathways and the insulin signaling cascade (see below “Tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6”), resistin may represent a link between inflammation and metabolic signals (123).

RETINOL BINDING PROTEIN 4

A potential link between retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) and type 2 diabetes was suggested by Yang et al. (124) reporting that RBP4 was elevated in insulin-resistant adipose specific GLUT4 knockout mice and humans with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Transgenic overexpression of human RBP4 in wildtype mice or administration of recombinant RBP4 to wildtype mice was shown to cause insulin resistance through induction of hepatic expression of the gluconeogenic enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and impairment of skeletal muscle insulin signaling. In contrast, genetic deletion of RBP4 enhanced insulin sensitivity. The effects of RBP4 may be mediated through retinol-dependent (via retinoic acid receptors [RARs] and retinoic acid-X receptors [RXRs] to regulate gene transcription) or retinol-independent mechanisms (for example, interaction with cell surface receptors such as Megalin/gp320). Serum RBP4 concentrations were elevated in insulin-resistant humans with obesity, impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes, and even in lean normoglycemic subjects with a strong family history of type 2 diabetes (124,125). A large number of subsequent studies confirmed an association of increased circulating RBP4 levels with various aspects of adiposity (126–129), insulin resistance (128,130–133), type 2 diabetes (127,134,135) and the metabolic syndrome (136). Improving insulin sensitivity by interventions such as exercise training, lifestyle modification, or gastric banding surgery reduced serum RBP4 levels in humans (125,126,137,138). Genetic studies reported an association of RBP4 SNPs and insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion, and/or type 2 diabetes (139,140). Other studies, however, failed to establish an association of RBP4 levels with obesity (141–143), insulin resistance (141–144), type 2 diabetes (144) or components of the metabolic syndrome (145). This discrepancy may be explained in part through methodological differences in the measurement of RBP4 (146) as well as differences in the study populations.

Based on current data, the function of RBP4 as an adipokine exerting metabolic effects in glucose metabolism in humans remains uncertain and might be restricted to rodent models (147).

TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR-α AND INTERLEUKIN-6

Both TNF-α and IL-6, the most widely studied cytokines produced by adipose tissue, were reported to modulate insulin resistance. Evidence supporting a key role for TNF-α in obesity-related insulin resistance came from studies showing that deletion of TNF-α or TNF-α receptors resulted in significantly improved insulin sensitivity in both diet-induced obese mice and leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (148). In humans, adipose tissue TNF-α expression correlated with BMI, percentage of body fat, and hyperinsulinemia, whereas weight loss decreased TNF-α levels (149). Fasting TNF-α plasma levels were associated with insulin resistance in the Framingham Offspring Study (19). Neutralization of TNF-α improved insulin resistance in obese rats (150). However, infusion of TNF-α-neutralizing antibodies to obese, insulin-resistant subjects, or type 2 diabetic patients, did not improve insulin sensitivity (151,152).

Conflicting data exist regarding the role of IL-6 in insulin resistance (153, 154). IL-6 was reported to reduce insulin-dependent hepatic glycogen synthesis (155,156) and glucose uptake in adipocytes (157), whereas insulin-dependent glycogen synthesis and glucose uptake was enhanced in myotubes (158,159). The effect of IL-6 on hepatic glucose production is still under debate (160,161). Kim et al. (160) reported that IL-6 infusion in mice blunted insulin’s ability to suppress hepatic glucose production. In contrast, Inoue et al. (161) demonstrated that intraventricular insulin infusion resulted in IL-6-mediated suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Overall, circulating IL-6 levels are increased in obese and insulin resistant subjects (162,163). One may speculate that persistent systemic increases of IL-6 in states of chronic inflammation such as obesity and type 2 diabetes may trigger insulin resistance, whereas transient increases may contribute to normal glucose homeostasis. TNF-α and IL-6 modulate insulin resistance through several distinct mechanisms, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1)-mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, IκB kinase (IKK)-mediated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation, and induction of SOCS-3 (164).

VASPIN

Visceral adipose tissue-derived serine protease inhibitor (vaspin) was identified in visceral adipose tissue of Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty rats at an age when body weight and hyperinsulinemia peaked (165). Vaspin expression was shown to decrease with worsening of diabetes and body weight loss. Administration of recombinant human vaspin to a mouse model of diet-induced obesity improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, suggesting that vaspin may represent an insulin-sensitizing adipokine. Human vaspin mRNA was reported to be expressed in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue. It was shown to be regulated in a fat-depot specific manner, and to be associated with obesity and parameters of insulin resistance (166). Likewise, elevated vaspin serum concentrations were correlated with obesity and impaired insulin sensitivity, whereas type 2 diabetes seemed to abrogate this correlation (167).

Much remains to be learned about the role of vaspin in glucose metabolism. Identification of vaspin’s protease substrate is crucial to understand how vaspin may modulate insulin resistance.

VISFATIN/PBEF/NAMPT

Visfatin, originally isolated as a presumptive cytokine named pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF) that enhances the maturation of B cell precursors (168), and displays nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt) activity (169), was reported to be highly correlated with the amount of visceral fat in humans and in a mouse model of obesity and insulin resistance, to exert insulin-mimetic effects in cultured cells, and to lower plasma glucose levels in mice (170). Although this study was retracted in 2007 due to numerous scientific flaws, the original observation was supported by a number of subsequent studies demonstrating that plasma visfatin levels in humans correlate with obesity, visceral fat mass, type 2 diabetes, and presence of the metabolic syndrome (171–173). Furthermore, visfatin promoter SNPs were reported to be associated with fasting glucose and insulin levels, as well as type 2 diabetes (174,175). Other studies, however, did not confirm an association of visfatin and visceral adipose tissue or parameters of insulin sensitivity in humans and rodents (176–179). Recent data pointed to an important role of visfatin/PBEF/Nampt in pancreatic β-cell function. In contrast to the results of Fukahara et al. (170), Revello et al. (180) demonstrated that the extracellular form of Nampt (eNampt/Visfatin/PBEF), which is secreted through a non-classical secretory pathway, did not show insulin-mimetic effects in vitro or in vivo, but rather exhibited robust nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) biosynthetic activity. Haplodeficiency and chemical inhibition of Nampt resulted in significantly decreased NAD biosynthesis and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic islets in vitro and in vivo. Conversely, administration of the Nampt reaction product nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) resulted in an amelioration of these defects.

In summary, current data suggest that adipose tissue as a natural source of eNampt/visfatin/PBEF may regulate β-cell function through secretion of eNampt and extracellular biosynthesis of NMN.

ADIPOKINE INTERPLAY

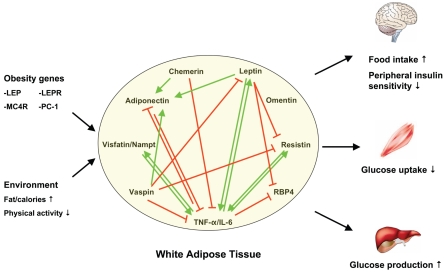

Insulin resistance should be conceptualized in a very broad manner that takes into account the interplay between nutrition, glucose, insulin and adipokines in various tissues of metabolic importance. Interactions between distinct adipokines add additional complexity to the picture (Table 1, Figure 1). Current data on adipokine interplay are rather sparse and, in part, contradictory due to examination of different in vitro (different cell types) and in vivo (different species) models.

Figure 1.

Obesity, adipokines and insulin resistance. Murine resistin is expressed in white adipose tissue, whereas in humans, resistin is mainly produced by peripheral-blood mononuclear cells. Green arrows depict stimulation, red lines suppression of gene expression.

Adiponectin and TNF-α control each other’s synthesis and activity, thus creating a balanced physiologic situation (164). Overnutrition results in activation of inflammatory pathways causing a critical imbalance leading to decreased expression of adiponectin. TNF-α and IL-6 play a key role in the regulation of many adipokines. TNF-α was reported to downregulate RBP4 production in human adipocytes (181). Expression of leptin (182,183), resistin (115), and visfatin/PBEF/eNampt (184) is increased by TNF-α and IL-6. Conversely, leptin (185), resistin (116–118), and visfatin/PBEF/eNampt (186) upregulate the production of TNF-α and IL-6, suggesting that these adipokines could trigger or participate in the inflammatory process through direct paracrine and/or autocrine actions. Leptin, however, also was reported to suppress the expression of resistin and RBP4 (92,187,188), and to increase adiponectin expression in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (188,189). Chemerin and vaspin, like adiponectin, were shown to have antiinflammatory properties. Chemerin inhibited the production of TNF-α and IL-6 by classically activated macrophages (64). Furthermore, knockdown of chemerin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes reduced adiponectin expression (63). Vaspin suppressed the expression of leptin, resistin, and TNF-α in white adipose tissue, yet increased the expression of adiponectin (165). No data have yet been reported on the interaction between omentin and other adipokines.

CONCLUSION

Obesity has reached dramatic proportions affecting more than 1 billion adults worldwide (190). The epidemic of obesity also affects children becoming overweight at progressively younger ages. Obesity is associated with an array of health problems including insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis, airway diseases, degenerative disorders, and various types of cancer. Our understanding of the pathogenesis of obesity and its metabolic sequelae has advanced significantly over the past decades. Environmental factors, such as sedentary lifestyle and increased calorie intake, in combination with an unfavorable genotype, are responsible for the epidemic of obesity. Excess visceral fat accumulation results in altered release of adipokines, leading to CNS-mediated skeletal muscle and hepatic insulin resistance (Figure 1). Understanding of the diverse effects of distinct adipokines and the interactions between these bioactive mediators is still incomplete. Unraveling the pathophysiological roles of adipokines in obesity-induced diseases likely will result in new pharmacotherapeutic approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BR 2151/4-1 to UCB).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26746–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10697–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotta K, et al. Circulating concentrations of the adipocyte protein adiponectin are decreased in parallel with reduced insulin sensitivity during the progression to type 2 diabetes in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 2001;50:1126–33. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fruebis J, et al. Proteolytic cleavage product of 30-kDa adipocyte complement-related protein increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle and causes weight loss in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041591798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001;7:947–53. doi: 10.1038/90992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamauchi T, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–6. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamauchi T, et al. Globular adiponectin protected ob/ob mice from diabetes and ApoE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2461–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Combs TP, et al. A transgenic mouse with a deletion in the collagenous domain of adiponectin displays elevated circulating adiponectin and improved insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology. 2004;145:367–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubota N, et al. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25863–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda N, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med. 2002;8:731–7. doi: 10.1038/nm724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawrocki AR, et al. Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2654–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamoto M, et al. Adiponectin induces insulin secretion in vitro and in vivo at a low glucose concentration. Diabetologia. 2008;51:827–35. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0944-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota N, et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 2007;6:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cnop M, et al. Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia. 2003;46:459–69. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschritter O, et al. Plasma adiponectin concentrations predict insulin sensitivity of both glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2003;52:239–43. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weyer C, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley AJ, et al. Associations of adiponectin with body fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic Hispanics and African-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2665–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. Adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell function. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:547–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hivert MF, et al. Associations of adiponectin, resistin, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3165–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotta K, et al. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1595–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilardini L, et al. Adiponectin is a candidate marker of metabolic syndrome in obese children and adolescents. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohan V, et al. Association of low adiponectin levels with the metabolic syndrome—the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-4) Metabolism. 2005;54:476–81. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, et al. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:172–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellmé F, et al. Circulating adiponectin levels are reduced in nonobese but insulin-resistant first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2003;52:1182–6. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winzer C, et al. Plasma adiponectin, insulin sensitivity, and subclinical inflammation in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1721–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsay RS, et al. Adiponectin and development of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian population. Lancet. 2002;360:57–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daimon M, et al. Decreased serum levels of adiponectin are a risk factor for the progression to type 2 diabetes in the Japanese Population: the Funagata study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2015–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snehalatha C, et al. Plasma adiponectin is an independent predictor of type 2 diabetes in Asian Indians. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3226–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spranger J, et al. Adiponectin and protection against type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 2003;361:226–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duncan BB, et al. Adiponectin and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes. 2004;53:2473–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krakoff J, et al. Inflammatory markers, adiponectin, and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1745–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snijder MB, et al. Associations of adiponectin levels with incident impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes in older men and women: The Hoorn Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2498–503. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mather KJ, et al. Adiponectin, change in adiponectin, and progression to diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes. 2008;57:980–6. doi: 10.2337/db07-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menzaghi C, Trischitta V, Doria A. Genetic influences of adiponectin on insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2007;56:1198–209. doi: 10.2337/db06-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waki H, et al. Impaired multimerization of human adiponectin mutants associated with diabetes: molecular structure and multimer formation of adiponectin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40352–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, et al. Posttranslational modifications on the four conserved lysine residues within the collagenous domain of adiponectin are required for the formation of its high-molecular-weight oligomeric complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16391–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pajvani UB, et al. Complex distribution, not absolute amount of adiponectin, correlates with thiazolidinedione-mediated improvement in insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12152–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blüher M, et al. Total and high-molecular weight adiponectin in relation to metabolic variables at baseline and in response to an exercise treatment program: comparative evaluation of three assays. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:280–5. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lara-Castro C, Luo N, Wallace P, Klein RL, Garvey WT. Adiponectin multimeric complexes and the metabolic syndrome trait cluster. Diabetes. 2006;55:249–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara K, Horikoshi M, Yamauchi T, et al. Measurement of the high molecular weight form of adiponectin in plasma is useful for the prediction of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1357–62. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Eynatten M, Lepper PM, Humpert PM. Total and high-molecular weight adiponectin in relation to metabolic variables at baseline and in response to an exercise treatment program: comparative evaluation of three assays: response to Bluher et al. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:e67. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Combs TP, et al. Induction of adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kilodaltons by PPARgamma agonists: a potential mechanism of insulin sensitization. Endocrinology. 2002;143:998–1007. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu JG, et al. The effect of thiazolidinediones on plasma adiponectin levels in normal, obese, and type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2002;51:2968–74. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeda N, et al. PPARgamma ligands increase expression and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, an adipose-derived protein. Diabetes. 2001;50:2094–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamauchi T, et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003;423:762–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuchida A, et al. Insulin/Foxo1 pathway regulates expression levels of adiponectin receptors and adiponectin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30817–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamauchi T, et al. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat Med. 2007;13:332–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hug C, et al. T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10308–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bjursell M, et al. Opposing effects of adiponectin receptors 1 and 2 on energy metabolism. Diabetes. 2007;56:583–93. doi: 10.2337/db06-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, et al. Deficiency of adiponectin receptor 2 reduces diet-induced insulin resistance but promotes type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2007;148:683–92. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blüher M, et al. Gene expression of adiponectin receptors in human visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue is related to insulin resistance and metabolic parameters and is altered in response to physical training. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:3110–5. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rasmussen MS, et al. Adiponectin receptors in human adipose tissue: effects of obesity, weight loss, and fat depots. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:28–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W, et al. Insulin-sensitizing effects of thiazolidinediones are not linked to adiponectin receptor expression in human fat or muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1301–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00312.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nannipieri M, et al. Pattern of expression of adiponectin receptors in human adipose tissue depots and its relation to the metabolic state. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1843–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, Holt H, Wang C, Hadid OH, Byrne CD. Expression of AdipoR1 in vivo in skeletal muscle is independently associated with measures of truncal obesity in middle-aged Caucasian men. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2058–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blüher M, et al. Circulating adiponectin and expression of adiponectin receptors in human skeletal muscle: associations with metabolic parameters and insulin resistance and regulation by physical training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2310–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Debard C, et al. Expression of key genes of fatty acid oxidation, including adiponectin receptors, in skeletal muscle of Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2004;47:917–25. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Civitarese AE, et al. Adiponectin receptors gene expression and insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic Mexican Americans with or without a family history of Type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47:816–20. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staiger H, et al. Expression of adiponectin receptor mRNA in human skeletal muscle cells is related to in vivo parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2004;53:2195–201. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crimmins NA, Martin LJ. Polymorphisms in adiponectin receptor genes ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2 and insulin resistance. Obes Rev. 2007;8:419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wittamer V, et al. Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids. J Exp Med. 2003;198:977–985. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bozaoglu K, et al. Chemerin is a novel adipokine associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4687–94. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goralski KB, et al. Chemerin: A novel adipokine that regulates adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28175–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cash JL, et al. Synthetic chemerin-derived peptides suppress inflammation through ChemR23. J Exp Med. 2008;205:767–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roh S-G, et al. Chemerin—A new adipokine that modulates adipogenesis via its own receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:1013–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashia M, et al. Chemerin enhances insulin signaling and potentiates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. FEBS Letters. 2008;582:573–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron. 1999;22:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bates SH, Myers MG., Jr The role of leptin receptor signaling in feeding and neuroendocrine function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prodi E, Obici S. Minireview: the brain as a molecular target for diabetic therapy. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2664–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coppari R, et al. The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab. 2005;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morton GJ, et al. Leptin regulates insulin sensitivity via phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signaling in mediobasal hypothalamic neurons. Cell Metab. 2005;2:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bates SH, Kulkarni RN, Seifert M, Myers MG., Jr Roles for leptin receptor/STAT3-dependent and –independent signals in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;1:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Minokoshi Y, et al. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002;415:339–43. doi: 10.1038/415339a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Niswender KD, Magnuson MA. Obesity and the beta cell: lessons from leptin. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2753–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI33528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morioka T, et al. Disruption of leptin receptor expression in the pancreas directly affects beta cell growth and function in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2860–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI30910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boghossian S, Dube MG, Torto R, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Hypothalamic clamp on insulin release by leptin transgene expression. Peptides. 2006;27:3245–54. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boghossian S, Lecklin AH, Torto R, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Suppression of fat deposition for the life time of rodents with gene therapy. Peptides. 2005;26:1512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The adipoinsular axis: effects of leptin on pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1–E14. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Munzberg H, Myers MG., Jr Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:566–570. doi: 10.1038/nn1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farooqi IS, et al. Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1093–103. doi: 10.1172/JCI15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oral EA, et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:570–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hukshorn CJ, et al. Weekly subcutaneous pegylated recombinant native human leptin (PEG-OB) administration in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4003–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.El-Haschimi K, Pierroz DD, Hileman SM, Bjørbaek C, Flier JS. Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1827–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Unger RH. Lipotoxic diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:319–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kalra SP. Central leptin insufficiency syndrome: an interactive etiology for obesity, metabolic and neural diseases and for designing new therapeutic interventions. Peptides. 2008;29:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang RZ, et al. Identification of omentin as a novel depot-specific adipokine in human adipose tissue: possible role in modulating insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1253–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00572.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.de Souza Batista CM, et al. Omentin plasma levels and gene expression are decreased in obesity. Diabetes. 2007;56:1655–61. doi: 10.2337/db06-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tan BK, et al. Omentin-1, a novel adipokine, is decreased in overweight insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Ex vivo and in vivo regulation of omentin-1 by insulin and glucose. Diabetes. 2008;57:801–8. doi: 10.2337/db07-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Steppan CM, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–12. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rajala MW, et al. Regulation of resistin expression and circulating levels in obesity, diabetes, and fasting. Diabetes. 2004;53:1671–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rajala MW, Obici S, Scherer PE, Rossetti L. Adipose-derived resistin and gut-derived resistin-like molecule-beta selectively impair insulin action on glucose production. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:225–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI16521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Satoh H, et al. Adenovirus-mediated chronic “hyper-resistinemia“ leads to in vivo insulin resistance in normal rats. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:224–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI20785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pravenec M, et al. Transgenic and recombinant resistin impair skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45209–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rangwala SM, et al. Abnormal glucose homeostasis due to chronic hyperresistinemia. Diabetes. 2004;53:1937–41. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Banerjee RR, et al. Regulation of fasted blood glucose by resistin. Science. 2004;303:1195–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Muse ED, et al. Role of resistin in diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:232–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI21270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim KH, Zhao L, Moon Y, Kang C, Sul HS. Dominant inhibitory adipocyte-specific secretory factor (ADSF)/resistin enhances adipogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6780–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305905101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Savage DB, et al. Resistin/Fizz3 expression in relation to obesity and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma action in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50:2199–2202. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Degawa-Yamauchi M, et al. Serum resistin (FIZZ3) protein is increased in obese humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5452–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Heilbronn LK, et al. Relationship between serum resistin concentrations and insulin resistance in nonobese, obese, and obese diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1844–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Youn BS, et al. Plasma resistin concentrations measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a newly developed monoclonal antibody are elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:150–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Osawa H, et al. The G/G genotype of a resistin singlenucleotide polymorphism at –420 increases type 2 diabetes mellitus susceptibility by inducing promoter activity through specific binding of Sp1/3. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:678–86. doi: 10.1086/424761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Osawa H, et al. Plasma resistin, associated with single nucleotide plymorphism –402, is correlated with insulin resistance, lower HDL cholesterol, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein in the Japanese general population. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1501–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ochi M, et al. Frequency of the G/G genotype of resistin single nucleotide polymorphism at –420 appears to be increased in younger-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2834–8. doi: 10.2337/db06-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gerber M, et al. Serum resistin levels of obese and lean children and adolescents: biochemical analysis and clinical relevance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4503–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen CC, et al. Serum resistin level among healthy subjects: Relationship to anthropometric and metabolic parameters. Metabolism. 2005;54:471–5. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pfutzner A, Langenfeld M, Kunt T, Lobig M, Forst T. Evaluation of human resistin assays with serum from patients with type 2 diabetes and different degrees of insulin resistance. Clin Lab. 2003;49:571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee JH, et al. Circulating resistin levels are not associated with obesity or insulin resistance in humans and are not regulated by fasting or leptin administration: cross-sectional and interventional studies in normal, insulin-resistant, and diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4848–56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kielstein JT, et al. Increased resistin blood levels are not associated with insulin resistance in patients with renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:62–6. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pagano C, et al. Increased serum resistin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to liver disease severity and not to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1081–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Perseghin G, et al. Increased serum resistin in elite endurance athletes with high insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1893–900. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beckers S, et al. Analysis of genetic variations in the resistin gene shows no associations with obesity in women. Obesity. 2008;16:905–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kaser S, et al. Resistin messenger-RNA expression is increased by proinflammatory cytokines in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nagaev I, Bokarewa M, Tarkowski A, Smith U. Human resistin is a systemic immune-derived proinflammatory cytokine targeting both leukocytes and adipocytes. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bokarewa M, Nagaev I, Dahlberg L, Smith U, Tarkowski A. Resistin, an adipokine with potent proinflammatory properties. J Immunol. 2005;174:5789–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Silswal N, et al. Human resistin stimulates the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-12 in macrophages by NF-κB-dependent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1092–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shetty GK, Economides PA, Horton ES, Mantzoros CS, Veves A. Circulating adiponectin and resistin levels in relation to metabolic factors, inflammatory markers, and vascular reactivity in diabetic patients and subjects at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2450–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Reilly MP, et al. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of atherosclerosis in humans. Circulation. 2005;111:932–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155620.10387.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Konrad A, et al. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of inflammatory bowel disease in humans. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:1070–4. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f16251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sunden-Cullberg J, et al. Pronounced elevation of resistin correlates with severity of disease in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1536–42. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266536.14736.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lehrke M, et al. An inflammatory cascade leading to hyperresistinemia in humans. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang Q, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–62. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Graham TE, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2552–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Haider DG, et al. Serum retinol-binding protein 4 is reduced after weight loss in morbidly obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1168–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jia W, et al. Association of serum retinol-binding protein 4 and visceral adiposity in Chinese subjects with and without type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3224–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Klöting N, et al. Serum retinol-binding protein is more highly expressed in visceral than in subcutaneous adipose tissue and is a marker of intra-abdominal fat mass. Cell Metab. 2007;6:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Aeberli I, et al. Serum retinol-binding protein 4 concentration and its ratio to serum retinol are associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome components in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4359–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Möhlig M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with insulin resistance, but appears unsuited for metabolic screening in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:517–23. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gavi S, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with insulin resistance and body fat distribution in nonobese subjects without type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1886–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Perseghin G, et al. Serum retinol-binding protein-4, leptin, and adiponectin concentrations are related to ectopic fat accumulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4883–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Stefan N, et al. High circulating retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with elevated liver fat but not with total, subcutaneous, visceral, or intramyocellular fat in humans. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1173–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Takebayashi K, Suetsugu M, Wakabayashi S, Aso Y, Inukai T. Retinol binding protein-4 levels and clinical features of type 2 diabetes patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2712–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cho YM, et al. Plasma retinol-binding protein-4 concentrations are elevated in human subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2457–61. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Qi Q, et al. Elevated retinol-binding protein 4 levels are associated with metabolic syndrome in Chinese people. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4827–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lim S, et al. Insulin-sensitizing effects of exercise on adiponectin and retinol binding protein-4 concentrations in young and middle-aged women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2263–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Balagopal P, et al. Reduction of elevated serum retinol binding protein in obese children by lifestyle intervention: association with subclinical inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1971–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Munkhtulga L, et al. Identification of a regulatory SNP in the retinol binding protein 4 gene associated with type 2 diabetes in Mongolia. Hum Genet. 2007;120:879–88. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Craig RL, Chu WS, Elbein SC. Retinol binding protein 4 as a candidate gene for type 2 diabetes and prediabetic intermediate traits. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:338–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Janke J, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 in human obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:2805–10. doi: 10.2337/db06-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yao-Borengasser A, et al. Retinol binding protein 4 expression in humans: relationship to insulin resistance, inflammation, and response to pioglitazone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2590–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Broch M, Vendrell J, Ricart W, Richart C, Fernández-Real JM. Circulating retinol-binding protein-4, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin disposition index in obese and nonobese subjects. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1802–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.von Eynatten M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome, but not with insulin resistance, in men with type 2 diabetes or coronary artery disease. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1930–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Silha JV, Nyomba BL, Leslie WD, Murphy LJ. Ethnicity, insulin resistance, and inflammatory adipokines in women at high and low risk for vascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:286–91. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Graham TE, Wason CJ, Blüher M, Kahn BB. Shortcomings in methodology complicate measurements of serum retinol binding protein (RBP4) in insulin-resistant human subjects. Diabetologia. 2007;50:814–23. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.von Eynatten M, Humpert PM. Retinol-binding protein-4 in experimental and clinical metabolic disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008;8:289–99. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-α function. Nature. 1997;389:610–4. doi: 10.1038/39335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Jellema A, Plat J, Mensink RP. Weight reduction, but not a moderate intake of fish oil, lowers concentrations of inflammatory markers and PAI-1 antigen in obese men during the fasting and postprandial state. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:766–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;1:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bernstein LE, Berry J, Kim S, Canavan B, Grinspoon SK. Effects of etanercept in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:902–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Dominguez H, et al. Metabolic and vascular effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade with etanercept in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:517–25. doi: 10.1159/000088261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mooney RA. Counterpoint: interleukin-6 does not have a beneficial role in insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:816–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01208a.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Point: interleukin-6 does have a beneficial role in insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:814–6. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01208.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Klover PJ, Zimmers TA, Koniaris LG, Mooney RA. Chronic exposure to interleukin-6 causes hepatic insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes. 2003;52:2784–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Senn JJ, Klover PJ, Nowak IA, Mooney RA. Interleukin-6 induces cellular insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Diabetes. 2002;51:3391–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.12.3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45777–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Carey AL, et al. Interleukin-6 increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in humans and glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in vitro via AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetes. 2006;55:2688–97. doi: 10.2337/db05-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Al Khalili L, et al. Signaling specificity of interleukin-6 action on glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3364–75. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Kim HJ, et al. Differential effects of interleukin-6 and -10 on skeletal muscle and liver insulin action in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1060–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Inoue H, et al. Role of hepatic STAT3 in brain-insulin action on hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 2006;3:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Pickup JC, Mattock MB, Chusney GD, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286–92. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E745–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Tilg H, Hotamisligil GS. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Cytokine-adipokine interplay and regulation of insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:934–45. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hida K, et al. Visceral adipose tissue-derived serine protease inhibitor: a unique insulin-sensitizing adipocytokine in obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504703102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Klöting N, et al. Vaspin gene expression in human adipose tissue: association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Youn BS, et al. Serum vaspin concentrations in human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:372–7. doi: 10.2337/db07-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Samal B, et al. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding a novel human pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1431–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Rongvaux A, et al. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, whose expression is upregulated in activated lymphocytes, is a nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, a cytosolic enzyme involved in NAD biosynthesis. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3225–34. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3225::AID-IMMU3225>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Fukuhara A, et al. Visfatin: a protein secreted by visceral fat that mimics the effects of insulin. Science. 2005;307:426–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1097243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Chen MP, et al. Elevated plasma level of visfatin/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:295–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Haider DG, et al. Increased plasma visfatin concentrations in morbidly obese subjects are reduced after gastric banding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1578–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Filippatos TD, et al. Increased plasma visfatin levels in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:71–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Bailey SD, et al. Common polymorphisms in the promoter of the visfatin gene (PBEF1) influence plasma insulin levels in a French-Canadian population. Diabetes. 2006;55:2896–902. doi: 10.2337/db06-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Zhang YY, et al. A visfatin promoter polymorphism is associated with low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:2119–26. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Berndt J, et al. Plasma visfatin concentrations and fat depot-specific mRNA expression in humans. Diabetes. 2005;54:2911–6. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Klöting N, et al. Vaspin gene expression in human adipose tissue: association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Pagano C, et al. Reduced plasma visfatin/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in obesity is not related to insulin resistance in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3165–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Oki K, Yamane K, Kamei N, Nojima H, Kohno N. Circulating visfatin level is correlated with inflammation, but not with insulin resistance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:796–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Revollo JR, et al. Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 2007;6:363–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Sell H, Eckel J. Regulation of retinol binding protein 4 production in primary human adipocytes by adiponectin, troglitazone and TNF-alpha. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2221–3. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Faggioni R, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Leptin regulation of the immune response and the immunodeficiency of malnutrition. FASEB J. 2001;15:2565–71. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0431rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Simons PJ, van den Pangaart PS, van Roomen CP, Aerts JM, Boon L. Cytokine-mediated modulation of leptin and adiponectin secretion during in vitro adipogenesis: evidence that tumor necrosis factor-alpha- and interleukin-1beta-treated human preadipocytes are potent leptin producers. Cytokine. 2005;32:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Hector J, et al. TNF-alpha alters visfatin and adiponectin levels in human fat. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:250–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Lago F, Dieguez C, Gómez-Reino J, Gualillo O. Adipokines as emerging mediators of immune response and inflammation. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:716–24. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Moschen AR, et al. Visfatin, an adipocytokine with proinflammatory and immunomodulating properties. J Immunol. 2007;178:1748–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Asensio C, Cettour-Rose P, Theander-Carrillo C, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Muzzin P. Changes of glycemia by leptin administration or high fat feeding in rodent models of obesity/type 2 diabetes suggest a link between resistin expression and control of glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2206–13. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Zhang W, Della\Fera MA, Hartzell DL, Hausman D, Baile CA. Adipose tissue gene expression profiles in ob/ob mice treated with leptin. Life Sci. 2008;83:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Delporte ML, El Mkadem SA, Quisquater M, Brichard SM. Leptin treatment markedly increased plasma adiponectin but barely decreased plasma resistin of ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E446–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Obesity and overweight. Geneva: World Health Organization; c2008. [cited 2008 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/facts/obesity/en. [Google Scholar]