Abstract

The Spot 14 (S14) gene is rapidly up-regulated by signals that induce lipogenesis such as enhanced glucose metabolism and thyroid hormone administration. Previous studies in S14 null mice show that S14 is required for normal lipogenesis in the lactating mammary gland, but not the liver. We speculated that the lack of a hepatic phenotype was due to the expression of a compensatory gene. We recently reported that this gene is likely an S14 paralog that we named S14-Related (S14-R). S14-R is expressed in the liver, but not in the mammary gland. If S14-R compensates for the absence of S14 in the liver, we hypothesized that, like S14, S14-R expression should be glucose responsive. Here, we report that hepatic S14-R mRNA levels increase with high-carbohydrate feeding in mice or within 2 h of treating cultured hepatocytes with elevated glucose. A potential carbohydrate response element (ChoRE) was identified at position −458 of the S14-R promoter. Deletion of or point mutations within the putative S14-R ChoRE led to 50–95% inhibition of the glucose response. Gel-shift analysis revealed that the glucose-activated transcription complex carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein/Max-like protein X (Mlx) binds to the S14-R ChoRE. Finally, S14-R glucose induction is completely blocked when a dominant-negative form of Mlx is overexpressed in primary hepatocytes. In conclusion, our results indicate that the S14-R gene is a glucose-responsive target of carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein/Mlx and suggest that the S14-R protein is a compensatory factor, at least partially responsible for the normal liver lipogenesis observed in the S14 null mouse.

THE ABILITY OF mammals to regulate the synthesis of long-chain fatty acids is critical for multiple physiological functions. Whenever excess calories as carbohydrate are consumed, it is advantageous for the animal to convert those calories to fat for storage and use at a time when calorie intake is less than the animal’s metabolic needs. In addition to the caloric storage function, mammals have also developed the ability to convert carbohydrate calories to lipids in the mammary gland to supply a denser source of calories to the nursing infant. The process of carbohydrate conversion to lipid is known as de novo lipogenesis. Expression of enzymes required for de novo lipogenesis is highly regulated in lipogenic tissues such as the liver and lactating mammary gland.

Carbohydrate feeding stimulates the transcription of many genes involved in de novo lipogenesis such as glucokinase, pyruvate kinase, acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, and malic enzyme (1,2,3). Both insulin and glucose are required to induce these genes. It has recently been shown for several of these genes that the glucose-signaling pathway requires a carbohydrate response element (ChoRE) in the promoter of these genes (4). This cis-acting sequence consists of two E boxes separated by 5 bp (5,6,7,8,9). The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)/leucine zipper proteins carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) and Max-like protein X (Mlx) bind to each E box of the ChoRE of these genes as a heterodimer in response to elevated hepatic glucose levels (10,11,12,13), and this binding is required for glucose-dependent activation of transcription.

We and others have reported that Spot 14 (S14) gene expression is regulated similarly to that of lipogenic enzyme genes (14,15,16,17). To gain insight into S14 protein function, we created a S14 null mouse and reported that this mouse shows normal hepatic lipogenesis (18) but markedly reduced lactating mammary gland lipogenesis (19). We have speculated that this discrepancy is due to expression of a related gene [S14-Related (S14-R); also known as Mig12)] that is expressed in the liver but not in the lactating mammary gland (19,20).

The S14-R gene is a paralog of S14. The S14-R gene is located on the X-chromosome both in humans and rodents (19), whereas the S14 gene is found on autosomal chromosomes (21,22,23,24,25). S14-R has recently been implicated as a protein associated with microtubules in cell culture (26). However, how this subcellular localization pattern relates to molecular function is not currently clear. We speculate that, regardless of mechanism, S14-R functionally regulates lipogenesis in a manner similar to that of S14. To gain further insight into the function of the S14 family of proteins, we have now studied the regulation of S14-R gene expression. In this report we show that the S14-R gene is regulated by carbohydrate feeding in vivo, and by glucose metabolism in cultured hepatocytes similar to the S14 gene. Furthermore, we identify a ChoRE in the S14-R promoter similar in sequence and function to previously identified ChoREs (27). We also show that the heterodimer ChREBP/Mlx binds to the S14-R ChoRE. Together, these data indicate that S14-R gene expression is directly regulated by glucose metabolism and that the S14-R protein may compensate for the absence of S14 in the S14 null mouse liver.

Materials and Methods

Animal use

All animal use and protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. S14 knockout and wild-type (WT) mice were created as previously described (18). The mice were subsequently backcrossed to a C57BL6/J strain 11 times to ensure that mice were studied on a congenic background. S14 null mice were generated by mating congenic S14 null males and females. WT mice were generated by breeding WT male and female mice obtained from S14 heterozygous matings.

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen free facility with a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle. Mice were given free access to food [Teklad diet 8640 (5% fat by weight, 14% fat calories); Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI] and water. Fasted mice had their food removed for 16 h overnight. Mice fed the high-carbohydrate diet were first fasted overnight and then fed a 60% sucrose diet (20% casein, 60% sucrose, fat free from Harlan-Teklad) for 4 d. All mice were killed between 0900 and 1100 h.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse tissue using a QIAGEN RNeasy MidiKit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using intron spanning primer sequences previously reported for S14 and S14-R genes (19). Annealing temperatures were 59 C for the S14 and S14-R primers. RT-PCR was conducted using the Roche LightCycler (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Reagents used for reactions were provided in the Roche SYBR Green 1 RNA amplification kit, and 100 ng total RNA was used for each reaction. Fluorescence data were acquired for 35 cycles, and the threshold crossing cycle was determined using LightCycler Software (version 3.5). For hepatocyte RNA, PCRs were conducted using an iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and the SYBR Green supermix from Bio-Rad Laboratories. Fold change in mRNA levels was determined using the 2Δ̂Δ threshold crossing cycle method previously described (28). All RT-PCR samples were also analyzed for ribosomal protein L32 as an internal control as previously described (19), and the level of the S14-R (or other tested mRNA) was normalized to the content of ribosomal protein L32.

Creation of S14-R reporter plasmids

Approximately 4000 bp (−4332 to +144) of the mouse S14-R gene were amplified by PCR and ligated to the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL4 (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). A region (−800 to −358) around the ChoRE (−458 to −431) was deleted by digesting the plasmid with AatII and AflII. The digested plasmid was isolated and reclosed by blunt ligation after filling in the AatII overhang. Point mutations within the ChoRE were created using the QuickChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Primary hepatocyte culture, transfection, and luciferase reporter assays

Male Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g) were fed ad libitum, and primary hepatocytes were isolated by the collagenase perfusion method previously described (29). After a 4-h attachment on 24-well CellBind plates (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY), cells were transfected using F1 reagent (Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) with 1 μg WT S14-R or mutant S14-R firefly promoter-reporter plasmids plus 12.5 ng Renilla luciferase (pRL-CMV; Promega) plasmid overnight as previously described (30). Media 199 containing 5.5 mm glucose, 23 mm HEPES, 10 nm dexamethasone, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 26 mm sodium bicarbonate, and 0.1 U/ml insulin served as the low-glucose media. Hepatocytes were maintained in low-glucose media or switched to high-glucose media (27.5 mm) and incubated for 24 h after transfection. Hepatocyte lysates were harvested the following morning in Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega), and dual luciferase assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Results are reported as Firefly/Renilla relative light units with a minimum sample size of three for each construct and treatment analyzed.

Identification of a S14-R ChoRE

Sequences of six previously identified ChoREs were used to search the rat, mouse, and human S14-R −15,000 to +3,000 promoter regions for similar ChoRE sequences. The search was conducted using the Transcription Element Search System web site (available at http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess) and analyzed using search strings from all known ChoREs as well as a perfect E-box sequence with appropriate spacing (CACGTGnnnnnCACGTG). Sequences that matched one or more of the test sequences at a minimum of nine of 12 positions and found in all three genomes within a region of sequence homology were selected for functional analysis.

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) whole cell extracts from cells transfected with FLAG epitope-tagged ChREBP and Mlx were used for EMSAs as previously described (30). A typical reaction contained 100,000 cpm 32P-labeled oligonucleotide and approximately 5 μg total protein. For reactions with antibody, proteins were first incubated with 3 μg FLAG antibody for 20 min at 4 C. After incubation with oligonucleotides for 30 min at room temperature, samples were loaded and separated on a 4.5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Results were visualized by phosphoimager analysis. The following oligonucleotides were annealed, filled in with Klenow (Large Fragment; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and used in the EMSA: E-boxes A and B [nt −463 to −438], 5′-GGGAGCACCCCATGTC-3′ (upper), 5′-GATTCACGTGGACATGGGGTGCT-CCC-3′ (lower); E-boxes B and C [nt −452 to −426], 5′-ATGTCCACGTGCATCCGGCATGTCCTG-3′ (upper), 5′-CAGGACATGCCGGATG-3′ (lower); and E-boxes A–C [nt −463 to −426], 5′-CAGGACATGCCGGATGCACGTGGACATGGGGTGCTCCC-3′ (upper), 5′-GGGAGCACCCC-ATGTCCACGTGCATC-3′ (lower). The ACC ChoRE positive control oligonucleotides used were previously reported (6).

Transcriptional reporter gene assay for measuring ChREBP activity

Hepatocytes were cultured in 12-well CellBind plates and transduced with adenovirus expressing either empty virus or dominant-negative (DN) Mlx, as previously described (11). The only difference between these adenoviruses is that the latter contains the cDNA corresponding to the DN Mlx. We used the Mlx b/a construct. This construct changes the basic arginine residues 87 and 88 to alanine and serine, respectively. The amount of virus used was determined empirically to give approximately 95% inhibition of the glucose response. After 2 h infection, hepatocytes were transfected using F1 reagent in low-glucose media. A mixture of firefly luciferase reporter (1 μg) driven by the S14-R promoter region and a Renilla control plasmid (12.5 ng) were transfected as described previously. Cells were cultured in low-glucose medium for an additional 24 h to allow expression of recombinant proteins. Subsequently, cells were maintained in low-glucose media or switched to high glucose (27.5 mm), and hepatocyte lysates were harvested the following day in Passive Lysis Buffer. Dual luciferase assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

All values are expressed as the mean ± sd for single experiments and ± sem for multiple experiments. Differences between groups were determined by ANOVA and post hoc testing with correction for the number of comparisons performed. A probability of less than 0.05 is reported as significantly different between groups.

Results

Lipogenic diet induces S14-R mRNA expression in mouse liver

We previously reported that de novo lipogenesis is normal in the adult S14 null mouse liver (18). We have subsequently shown that a related gene (S14-R) is expressed in the liver and proposed that S14-R compensates for the loss of S14 protein in S14 null mouse liver (19). We hypothesized that if the S14 and S14-R gene products are functionally equivalent, regulation of S14 and S14-R gene expression should be controlled in response to similar physiological stimuli. Because the S14 gene is regulated by dietary carbohydrate in the liver, we asked whether dietary carbohydrate also regulates hepatic S14-R expression.

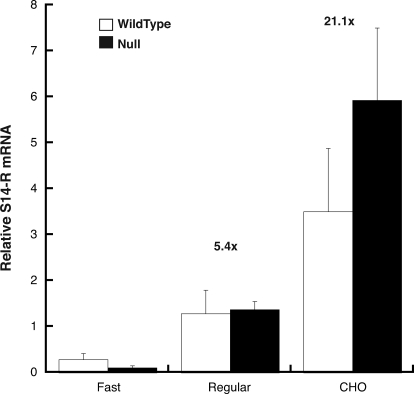

We first measured hepatic S14-R expression in WT and S14 null mice under three dietary states: 16 h fasting; ad libitum chow feeding; or 16 h fasting, followed by refeeding a high-carbohydrate diet for 4 d. Figure 1 shows that the transition from the fasted to fed states results in a 5-fold increase in S14-R mRNA levels in both WT and S14 null mouse liver. Furthermore, feeding a high-carbohydrate diet resulted in a further increase in S14-R mRNA levels (a 14- and 24-fold increase for WT and S14 null mice, respectively). These changes in S14-R mRNA occur in parallel with changes in the mRNAs for the lipogenic enzymes fatty acid synthase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which were similarly induced by dietary carbohydrate (data not shown). Together these data indicate that S14-R mRNA levels are induced by feeding a lipogenic diet, and deletion of the S14 gene does not affect S14-R induction in the liver. Indeed, the fold induction of S14-R in the null animal was greater than that in the wild type, consistent with compensatory function of S14-R in the absence of S14.

Figure 1.

S14-R gene expression is regulated by dietary carbohydrate. S14 WT (white bars) or null (black bars) mice were either fasted (fast) overnight, maintained on a regular rodent chow (Regular), or fasted and then fed a 60% sucrose diet (CHO) for 4 d. Liver S14-R mRNA was measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Each bar represents the mean ± sem from three animals per group. There was no difference in expression between genotypes, so the genotypes were pooled for statistical analysis. Each dietary treatment was significantly different from the other by ANOVA. The fold change (over fasting) is indicated above each bar. The fold change in S14 mRNA in the same samples was 6.7 ± 1.1 and 23.4 ± 11.2 in Regular and CHO fed mice, respectively.

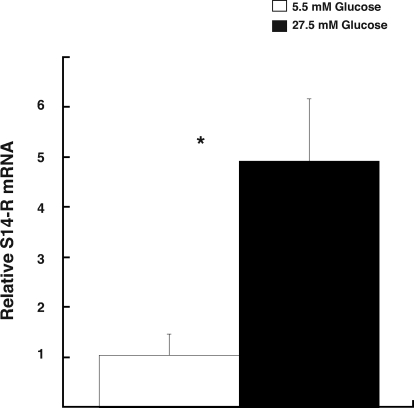

S14-R mRNA levels are induced by glucose in primary hepatocytes

To determine whether effects of diet on liver expression occur directly on the hepatocyte, we measured the S14-R glucose response in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. We hypothesized that, similar to other hepatic lipogenic genes, S14-R expression should be induced by a glucose signal. Figure 2 shows that the S14-R gene responds to glucose very rapidly with a 5-fold induction observed after 2 h culturing in high glucose (27.5 vs. 5.5 mm). These changes are observed in cells incubated at constant insulin levels, so that changes represent responses to glucose rather than insulin. Included in the figure legend is the response of the positive control, S14 mRNA. Thus, the S14-R gene responds to glucose similarly to S14 (and other lipogenic genes) both in vivo and in primary hepatocyte culture. We found that the 5-fold increase in S14-R mRNA was sustained for at least 24 h (data not shown).

Figure 2.

S14-R mRNA is induced by high glucose in hepatocytes. Primary rat hepatocytes were isolated and cultured in low-glucose (5.5 mm) media 199 overnight. The following day, cells were treated with low or high-glucose (27.5 mm) media for 2 h, and total RNA was isolated. RT-PCR was performed using S14-R primers from total cell cDNA as described in the Materials and Methods section. Each bar represents the mean ± sem of three samples from one experiment. The S14-R mRNA levels were significantly different (*) at 2 h incubation. In the same samples, the S14 mRNA showed a 55 ± 7-fold induction.

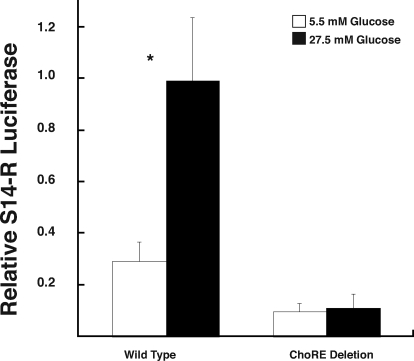

The S14-R promoter is responsive to glucose and contains a ChoRE

Because S14-R responds to dietary carbohydrate stimuli similarly to that of the S14 gene, and the response to glucose in culture is rapid, we proposed that the S14-R gene contains a ChoRE as reported for the S14 gene (31,32). Thus, we searched for ChoRE E-box sequences in silico from −15,000 to +3,000 bases relative to the transcriptional start site. We identified one region from −458 to −431 from the transcriptional start site that contained nucleotide sequence similar to other ChoREs identified to date. This sequence conformed to a proposed consensus ChoRE sequence recently reported to be necessary for ChREBP/Mlx binding (27,33).

To test the possibility that this region contains a ChoRE, we cloned the S14-R promoter and placed it upstream of a luciferase reporter gene. As expected, we observed a robust glucose-dependent induction of WT promoter activity (Fig. 3). We next deleted approximately 400 bases (−800 to −358) around the region carrying the putative ChoRE. As shown in Fig. 3, this deletion completely eliminated the response of the S14-R promoter to glucose. Therefore, this promoter region is necessary for the glucose-dependent activation of S14-R transcription.

Figure 3.

A 400-bp region of the S14-R promoter is necessary for glucose-dependent promoter activation. Primary rat hepatocytes were cotransfected with luciferase reporter plasmid containing either the WT S14-R promoter luciferase reporter, or the ChoRE deleted (400 bp surrounding the putative ChoREs) promoter luciferase reporter. After overnight incubation in media containing 5.5 mm glucose, the media were changed to contain the indicated glucose concentration. After 24 h, hepatocytes were harvested, and luciferase activity was measured with normalization to Renilla activity. The values are mean ± sd of three samples from one of three experiments. The asterisk indicates a significant (P < 0.05) difference between 5.5 and 27.5 mm glucose with the WT promoter.

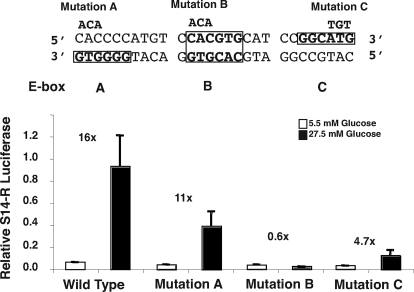

To evaluate further the proposed ChoRE, we mutated specific nucleotides within individual E boxes to determine whether each were necessary for glucose-dependent S14-R promoter activation. The putative ChoRE of the S14-R gene consists of a perfect E box (CACGTG), designated box B, surrounded by two E-box-like motifs (boxes A and C), each spaced at 5 bp from box B. Compared with wild type, we observed significant effects in promoter activity for each of the mutants constructed (Fig. 4). Mutation to E-box B resulted in a 95% decrease in S14-R promoter activity under high-glucose conditions and about a 50% decrease under low-glucose conditions. This lack of activity for E-box B mutation implies that this E box is essential for glucose-dependent transcriptional activation. Mutation to the E-box-like sequences A or C also decreased S14-R promoter activity from approximately 50–80%, respectively. The individual mutation to E-boxes A or C also lowered activity under low-glucose similarly to the E-box B mutation. Thus, the region containing the potential ChoRE sequences in the S14-R promoter was indeed essential for supporting the functional response to glucose.

Figure 4.

ChoRE E-box mutations block glucose-dependent activation of the S14-R promoter. Primary rat hepatocytes were cultured and cotransfected with S14-R reporter constructs as described in Fig. 3. The sequence above the bar graph depicts the S14-R ChoRE (−458 to − 431). The E boxes are in bold and outlined by a rectangle. The highlighting of alternative strands represents the putative vectorial binding of ChREBP-Mlx heterodimers. Three bases were mutated per E box. The base mutations are indicated above each E box. Mutant S14-R promoters were positioned upstream of a luciferase reporter gene. White bars represent hepatocytes incubated in 5.5 mm glucose, and black bars represent hepatocytes incubated in 27.5 mm glucose media. Each bar represents the mean ± sem of five samples. Statistics were performed on log-transformed data to correct for inhomogeneity of variances. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with post hoc testing by the Bonferroni method. High glucose significantly (P < 0.002) induced all promoters except mutation B. The high-glucose value of the WT promoter was significantly (P < 0.0002) greater than promoter mutations B and C.

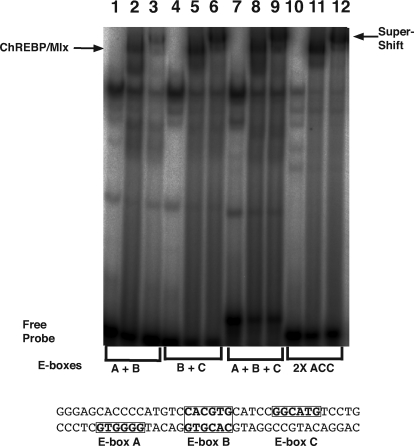

The ChoRE regions from lipogenic enzyme genes function by binding to a pair of heterodimers of the bHLH proteins ChREBP and Mlx. Optimal heterodimer binding and ChoRE activity occur with two E boxes separated by five bases, thus binding a pair of heterodimers. To evaluate whether these factors bind to the functional ChoRE sequences in the S14-R promoter, we performed EMSA analysis. HEK293 cells were transfected with ChREBP and Mlx, and total cell lysates were prepared. Lysates were incubated with radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing S14-R E-box sequences (Fig. 5). We observed that an oligonucleotide containing all three E boxes (lane 8) yielded a band that was not observed with control HEK293 cell extracts (lane 7). This band co-migrated with that observed for binding of ChREBP/Mlx to a positive control containing the well-characterized ChoRE from the ACC gene (lane 11). A similar band was observed with a shorter oligonucleotide containing boxes B and C (lane 5), consistent with the dramatic reduction in glucose responsiveness when either the B or C motifs were mutated. When incubated with an oligonucleotide containing E-boxes A and B, there was minimal binding of ChREBP/Mlx (lane 2). This result correlated well with the luciferase reporter data where there was a negligible effect on the high-glucose response when E-box A was mutated. We confirmed that the proteins that bound were in fact ChREBP/Mlx by performing super-shifts using antibodies that recognize ChREBP, as shown in lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12 (right arrow). Lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10 were negative controls of untransfected (no ChREBP/Mlx) cell extracts with the various labeled oligonucleotides. Given the results observed in the reporter assays of the S14-R promoter as well as the EMSAs described previously, we propose that S14-R is a glucose responsive gene that is activated upon ChREBP/Mlx binding to a bona fide ChoRE.

Figure 5.

ChREBP/Mlx binds to the S14-R ChoRE. An EMSA was performed with HEK293 whole cell lysates transfected with either cytomegalovirus empty vector (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10) or ChREBP/Mlx (other lanes). Each binding reaction contained various 32P-radiolabeled probes. The probes used were oligonucleotides containing the listed E boxes from the rat S14-R promoter sequence, as well as the 2×ACC ChoRE as a positive binding control. The left arrow indicates ChREBP/Mlx binding relative to control lanes. Lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12 were preincubated with FLAG antibody, which super-shifts the FLAG-ChREBP (right arrow) and allowed for the confirmation of ChREBP/Mlx proteins bound to the ChoREs tested. The other bands noted on this figure represent nonspecific binding of the probe to other proteins.

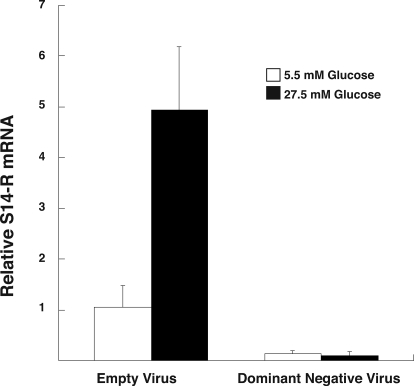

To confirm further the functional nature of the identified ChoRE, we infected primary hepatocytes with an adenovirus that expresses a DN form of Mlx. DN Mlx binds to endogenous ChREBP and prevents ChREBP from binding to WT endogenous Mlx. Because the DN Mlx has several highly conserved basic residues mutated, it is unable to bind to DNA. Thus, the DN Mlx-ChREBP complex cannot bind to a ChoRE, leading to inhibition of glucose-dependent transcriptional activation through a ChoRE. Figure 6 demonstrates that infection of primary hepatocytes with DN Mlx prevents the carbohydrate induction of S14-R mRNA relative to cells treated with the empty virus control. Thus, both by EMSA and functional response, we have shown that the S14-R promoter contains a ChoRE that binds and requires ChREBP/Mlx heterodimer for glucose responsivity.

Figure 6.

Glucose-dependent S14-R induction is blocked by DN Mlx. Primary rat hepatocytes were transduced with recombinant adenovirus expressing empty virus or DN Mlx. The cells were incubated for 24 h in low-glucose medium to allow for viral expression and then treated with low or high-glucose media for 24 additional hours. Hepatocyte RNA was isolated and S14-R mRNA measured by quantitative RT-PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section. Each bar is the mean ± sd of three samples expressed relative to the low-glucose empty virus sample. Data were analyzed by ANOVA after log transforming the data to equalize the variances. Glucose treatment significantly (P < 0.001) increased S14-R mRNA in hepatocytes treated with the empty virus. S14-R mRNA levels were significantly reduced in hepatocytes treated with the DN virus compared with hepatocytes treated with the empty virus. The difference was noted in hepatocytes cultured in both glucose concentrations (P < 0.03 at low glucose; P < 0.0001 at high glucose). Glucose had no effect in hepatocytes treated with the DN virus.

Discussion

Our previous studies had identified the S14-R gene as a paralog of the S14 gene (19). Because S14-R mRNA was expressed in the liver, this led us to speculate that the S14-R gene may compensate for the lack of the hepatic S14 gene in S14 null mice. Increasing de novo lipogenesis in the liver by feeding of a high-carbohydrate diet or treatment with thyroid hormone is accompanied by a dramatic induction of S14 gene expression. We propose that this increased S14 expression is necessary to support enhanced lipogenesis. Therefore, a corollary of the hypothesis that S14-R can compensate for S14 is that the S14-R gene would respond to dietary stimuli similarly to the S14 gene. We now have shown that S14-R gene expression is induced by dietary carbohydrate in vivo and high glucose in culture, similar to that of the S14 gene. Furthermore, we have identified a ChoRE in the promoter of the S14-R gene, shown that ChREBP/Mlx binds to this ChoRE, and inhibition of ChREBP binding to the ChoRE prevents the glucose-dependent induction of S14-R. Therefore, the S14-R protein may compensate for the lack of the S14 protein in the S14 null mouse liver. The presence of S14-R protein in the liver and its absence in mammary tissue (19) can explain the observed normal hepatic lipogenesis but diminished lactating mammary gland lipogenesis in the S14 null mouse.

Our data also expand the number of carbohydrate responsive genes that contain an identified and functional ChoRE. There are relatively few genes that have been well studied with respect to carbohydrate/glucose responsiveness both in vivo and in culture. Most of these genes have known function in the lipogenic pathway and include acetyl-CoA carboxylase (34), fatty acid synthase (35), and pyruvate kinase (36). In addition, the S14 gene has been extensively studied and classified as a lipogenic gene, although its true function has yet to be identified (20,37). Both early studies using mRNA activity profiles (38,39) and recent studies using gene expression arrays (27) have indicated that many other hepatic genes are carbohydrate responsive. To understand fully the mechanism of the carbohydrate responsiveness, it is important to identify both the cis- and trans-elements that are involved in the activation of such genes. In this manuscript we show that the S14-R gene is another such carbohydrate responsive gene and that the S14-R promoter contains a ChoRE that binds ChREBP/Mlx.

It is interesting to note that the ChoRE located in the S14-R gene is distinctly different from the elements described in the other well-studied carbohydrate responsive genes. The ChoREs in those genes consist of two E-box sequences separated by 5 bp. We found that the S14-R gene contains three E-box sequences, each separated by 5 bp. Thus, the S14-R gene has two potential ChoREs, each sharing a common E-box sequence (E-box B in Fig. 4). It is not surprising that a mutation in this common E-box sequence eliminates all glucose responsiveness. However, it was surprising that mutation of E-box C also led to the almost complete loss of glucose responsiveness, whereas mutation of E-box A had only a minor affect on the response to glucose. We conclude from those data that the 3′-most E-box pair must be the dominant ChoRE in this gene and that the 5′-pair likely only plays a minor role in responding to glucose. This is supported by the EMSA data showing poor binding to the 5′-pair (E-boxes A and B, Fig. 5), and the greater similarity of the 3′-pair (E-boxes B and C) compared with the 5′-pair to the consensus ChoRE (27). It is also important to emphasize that elimination of the carbohydrate response with mutation of E-box B makes it very unlikely that other E-boxes 5′- of E-box A or 3′- of E-box C play a significant role in the glucose response. Whether other glucose responsive genes contain a similar configuration of ChoREs, or whether the set of genes that do not respond as robustly to glucose contain a ChoRE similar to the 5′-pair, remains to be determined.

Finally, it is worth commenting on the possible function of the S14-R protein in lipogenesis. This protein was first described as a Mid1 interacting protein (Mig12) (26), and it was proposed that S14-R (Mig12) had a function related to microtubular stabilization in the nervous system. Whether or not S14-R does stabilize microtubules in the central nervous system has yet to be determined in vivo. Furthermore, the S14 protein is known to have a protein-protein interaction domain (40), which accounts for an ability to homodimerize. A similar domain in the S14-R protein, which allows it to interact with Mid1 (26), may allow S14-R to interact with S14. We believe the similarity of S14-R amino acid sequences to the S14 protein and its expression in lipogenic tissue raises the possibility that S14-R functions similarly to S14 in such tissues. We have speculated on the functional role of S14 (20) based on the fact that mammary gland lipogenesis is highly dependant on the expression of S14 (19,37), but the in vitro measurement of lipogenic enzyme activity is not altered by the lack of S14 protein. If S14-R acts in a manner analogous to S14, we would expect that elimination of both S14 and S14-R would lead to near complete inhibition of de novo hepatic lipogenesis.

In conclusion, we have shown that the S14-R gene is induced by carbohydrate feeding in vivo and by glucose in culture. We have identified the ChoRE on the S14-R gene. This ChoRE binds to the bHLH protein heterodimer ChREBP and Mlx, and this heterodimer is required for the S14-R response to glucose in primary hepatocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Christoferson, Mary Jo Zurbey, Luke N. Robinson, and Brennon O'Callaghan for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

This project was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32-DK007203, NIH P30-DK50456, NIH R01-DK26919 and a grant-in-aid from the Minnesota Medical Foundation.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online June 12, 2008

Abbreviations: bHLH, Basic helix-loop-helix; ChoRE, carbohydrate response element; ChREBP, carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein; CoA, coenzyme A; DN, dominant-negative; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293; Mlx, Max-like protein X; S14, Spot 14; S14-R, Spot 14-Related; WT, wild type.

References

- Girard J, Ferre P, Foufelle F 1997 Mechanisms by which carbohydrates regulate expression of genes for glycolytic and lipogenic enzymes. Annu Rev Nutr 17:325–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towle HC, Kaytor EN, Shih HM 1997 Regulation of the expression of lipogenic enzyme genes by carbohydrate. Annu Rev Nutr 17:405–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaulont S, Vasseur-Cognet M, Kahn A 2000 Glucose regulation of gene transcription. J Biol Chem 275:31555–31558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towle HC 2005 Glucose as a regulator of eukaryotic gene transcription. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergot MO, Diaz-Guerra MJ, Puzenat N, Raymondjean M, Kahn A 1992 Cis-regulation of the L-type pyruvate kinase gene promoter by glucose, insulin and cyclic AMP. Nucleic Acids Res 20:1871–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan BL, Koo SH, Wu Y, Freake HC, Towle HC 2001 Glucose regulation of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase promoter PI in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 276:16033–16039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufo C, Gasperikova D, Clarke SD, Teran-Garcia M, Nakamura MT 1999 Identification of a novel enhancer sequence in the distal promoter of the rat fatty acid synthase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261:400–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih HM, Liu Z, Towle HC 1995 Two CACGTG motifs with proper spacing dictate the carbohydrate regulation of hepatic gene transcription. J Biol Chem 270:21991–21997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KS, Towle HC 1991 Localization of the carbohydrate response element of the rat L-type pyruvate kinase gene. J Biol Chem 266:8679–8682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka K, Bruick RK, Liang G, Horton JD, Uyeda K 2004 Deficiency of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) reduces lipogenesis as well as glycolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7281–7286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Tsatsos NG, Towle HC 2005 Direct role of ChREBP.Mlx in regulating hepatic glucose-responsive genes. J Biol Chem 280:12019–12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckman AK, Ma L, Towle HC 2004 Mlx is the functional heteromeric partner of the carbohydrate response element-binding protein in glucose regulation of lipogenic enzyme genes. J Biol Chem 279:15662–15669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Takenoshita M, Sakurai M, Bruick RK, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Arnot D, Uyeda K 2001 A glucose-responsive transcription factor that regulates carbohydrate metabolism in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9116–9121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jump DB, Oppenheimer JH 1985 High basal expression and 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine regulation of messenger ribonucleic acid S14 in lipogenic tissues. Endocrinology 117:2259–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlaw WB, Church JL, Harmon J, Mariash CN 1995 Direct evidence for a role of the “spot 14” protein in the regulation of lipid synthesis. J Biol Chem 270:16615–16618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariash CN, Seelig S, Schwartz HL, Oppenheimer JH 1986 Rapid synergistic interaction between thyroid hormone and carbohydrate on mRNAS14 induction. J Biol Chem 261:9583–9586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih HM, Towle HC 1995 Matrigel treatment of primary hepatocytes following DNA transfection enhances responsiveness to extracellular stimuli. Biotechniques 18:813–814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Mariash A, Margosian MR, Gopinath S, Fareed MT, Anderson GW, Mariash CN 2001 Spot 14 gene deletion increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis. Endocrinology 142:4363–4370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Anderson GW, Mucha GT, Parks EJ, Metkowski JK, Mariash CN 2005 The Spot 14 protein is required for de novo lipid synthesis in the lactating mammary gland. Endocrinology 146:3343–3350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFave LT, Augustin LB, Mariash CN 2006 S14: insights from knockout mice. Endocrinology 147:4044–4047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillasca JP, Gastaldi M, Khiri H, Dace A, Peyrol N, Reynier P, Torresani J, Planells R 1997 Cloning and initial characterization of human and mouse Spot 14 genes. FEBS Lett 401:38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncur JT, Park JP, Maloney M, Mohandas TK, Kinlaw WB 1997 Assignment of the “spot 14” gene (THRSP) to human chromosome band 11q13.5 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet 78:131–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncur JT, Park JP, Memoli VA, Mohandas TK, Kinlaw WB 1998 The “Spot 14” gene resides on the telomeric end of the 11q13 amplicon and is expressed in lipogenic breast cancers: implications for control of tumor metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6989–6994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota Y, Mariash A, Wagner JL, Mariash CN 1997 Cloning, expression and regulation of the human S14 gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 126:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw CW, Towle HC 1984 Characterization of a thyroid hormone-responsive gene from rat. J Biol Chem 259:7253–7260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti C, Fontanella B, Ferrentino R, Meroni G 2004 Mig12, a novel Opitz syndrome gene product partner, is expressed in the embryonic ventral midline and co-operates with Mid1 to bundle and stabilize microtubules. BMC Cell Biol 5:9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Robinson LN, Towle HC 2006 ChREBP*Mlx is the principal mediator of glucose-induced gene expression in the liver. J Biol Chem 281:28721–28730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-δ δ C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaytor EN, Shih H, Towle HC 1997 Carbohydrate regulation of hepatic gene expression. Evidence against a role for the upstream stimulatory factor. J Biol Chem 272:7525–7531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsos NG, Towle HC 2006 Glucose activation of ChREBP in hepatocytes occurs via a two-step mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 340:449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih H, Towle HC 1994 Definition of the carbohydrate response element of the rat S14 gene. Context of the CACGTG motif determines the specificity of carbohydrate regulation. J Biol Chem 269:9380–9387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo Y, Goto Y, Mariash CN 1993 Location of a glucose-dependent response region in the rat S14 promoter. Endocrinology 133:1221–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Sham YY, Walters KJ, Towle HC 2007 A critical role for the loop region of the basic helix-loop-helix/leucine zipper protein Mlx in DNA binding and glucose-regulated transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 35:35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownsey RW, Boone AN, Elliott JE, Kulpa JE, Lee WM 2006 Regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochem Soc Trans 34:223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre P 1999 Regulation of gene expression by glucose. Proc Nutr Soc 58:621–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geelen MJ, Harris RA, Beynen AC, McCune SA 1980 Short-term hormonal control of hepatic lipogenesis. Diabetes 29:1006–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlaw WB, Quinn JL, Wells WA, Roser-Jones C, Moncur JT 2006 Spot 14: A marker of aggressive breast cancer and a potential therapeutic target. Endocrinology 147:4048–4055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig S, Liaw C, Towle HC, Oppenheimer JH 1981 Thyroid hormone attenuates and augments hepatic gene expression at a pretranslational level. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:4733–4737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr FE, Bingham C, Oppenheimer JH, Kistner C, Mariash CN 1984 Quantitative investigation of hepatic genomic response to hormonal and pathophysiological stimuli by multivariate analysis of two-dimensional mRNA activity profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BA, Maloney M, Kinlaw WB 1997 Spot 14 protein-protein interactions: evidence for both homo- and heterodimer formation in vivo. Endocrinology 138:5184–5188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]