Abstract

Endothelin (ET)-1 stimulates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases and increases superoxide production in some cells such as vascular smooth muscle cells. Here, we reported that ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide generation, and cell proliferation in human abdominal aortic endothelial cells (HAAECs) via the ETB1-Pyk2-Rac1-Nox1 pathway. Superoxide production was determined by assessing ethidium fluorescence using flow cytometry in HAAECs exposed to ET1 (10–30 nm) at different time intervals. ET1 significantly decreased superoxide production in HAAECs in the presence of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, indicating that ET1 suppressed superoxide generation independent of nitric oxide synthase. ET1 significantly attenuated NADPH oxidase activity and cell proliferation, which could be abolished by silence of Nox1 gene, suggesting that ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity was mediated by Nox1. Furthermore, RNA interference silence of ETB1 receptors significantly increased NADPH oxidase activity, and blocked the inhibitory effect of ET1 on NADPH oxidase activity. Activation of ETB1 receptors by ET1 suppressed protein phosphorylation of pyk2 (Y402) and Rac1, suggesting that ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity via ETB1-Pyk2-Rac1 pathway. Indeed, inhibition of Pyk2 by AG-17 abolished ET1-induced suppression of NADPH oxidase activity. ET1 also attenuated angiotensin II-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and cell proliferation. This study demonstrated, for the first time, that ET1, via ETB1, inhibited NADPH oxidase activity in HAAECs by suppressing the Pyk2-Rac1-Nox1 pathway. This finding reveals a novel function of ETB1 receptors in regulating endothelial NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide production, and cell proliferation, opening a new avenue for understanding the role of ETB1 receptors in protecting endothelial cells.

THE ENDOTHELIN (ET) system is essential for the maintenance of normal blood pressure and regulation of vascular tone. The vascular endothelial cells are the major source of ETs. ETs bind to two different types of receptors termed ETA and ETB, which belong to a large family of transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (1). ETA receptors are highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and activation of ETA receptors leads to vasoconstriction. There are two types of ETB receptors, ETB1 and ETB2, due to alternative splicing from a single gene (2). ETB2 receptors are expressed in VSMCs, and activation of ETB2 receptors results in vasoconstriction and cell proliferation. In contrast, ETB1 receptors are expressed in endothelial cells (3), and activation of ETB1 receptors stimulates production of nitric oxide (NO) and release of prostaglandins, leading to vasodilatation (1,4). Thus, the actual balance between ETA and ETB1 receptor activity may contribute to the pathogenesis of vascular diseases (5). ET1 has been shown to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels by activating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases via ETA or ETB2 receptor in VSMCs (6,7). Up-regulation of ETB2 receptors occurred in VSMCs in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension, which was thought to be important in mediating the enhanced vascular contractile responses to ET1 (8). ET1 enhanced ROS generation by directly up-regulating NADPH oxidase in the carotid arteries of DOCA-salt rats (7) and in cultured pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (6).

Nox1, a homolog of gp91phox, is considered involved in signal transduction in VSMCs in hypertension and vascular dysfunction (9,10). Nox1 is a mitogenic oxidase that is responsible for cell growth and proliferation. Nox1 plays an important role in constitutive production of superoxide in VSMCs (11) and is involved in vascular injury (12). Considerable attention has been paid to the stimulating effect of ET1/ETA on NADPH oxidases in the generation of ROS in VSMCs (6,7,13,14). However, it is not clear about the relationship between ETB1 receptors and Nox1-dependent superoxide production in endothelial cells. The study of the relationship of ETB1 and Nox1 may lead to a new understanding of ET1 in the regulation of endothelial function and dysfunction. We hypothesized that activation of ETB1 receptors attenuates NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide production, and cell proliferation in human abdominal aortic endothelial cells (HAAECs). The objective of this study was to understand the role of ETB1 receptors in mediating signaling pathways in the regulation of NADPH oxidase activity in HAAECs.

Rac1 is an important regulator of the NADPH oxidase activity in phagocytes and nonphagocytes (15,16,17,18). ET1 is known to activate proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) in cardiomyocytes via ETA (16). Pyk2 activates Rac1, leading to the activation of NADPH oxidase (18). ET1 causes rapid activation of Rac1 in neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. We hypothesized that activation of ETB1 receptors inhibits NADPH oxidase activity by suppressing the Pyk2-Rac1-Nox1 pathway in the HAAECs. The study of ETB1 signaling pathway mediating inhibition of NADPH oxidase may reveal new insights into the role of ETB1 receptors in protecting endothelial cells and endothelial function.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HAAECs (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured using precoated 0.1% porcine gelatin. Cells were grown at 37 C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in F-12K culture medium containing l-glutamine (2 mm), sodium bicarbonate (1.5 g/liter), heparin (0.1 mg/ml), endothelial growth supplement (0.03 mg/ml), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), and 10% fetal bovine serum.

Effects of ET1 on superoxide generation in HAAECs

Superoxide generation in HAAECs was measured as described earlier (19). Briefly, cells were incubated with NO inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (0.1 mm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 1 h before the treatment with ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min (Assay Designs, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). Cells were harvested with trypsin and resuspended in phenol red free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (106 cells/ml). Cells were then incubated with dihydroethidium (DHE) (5 μm) in PBS at 37 C in the dark for 30 min in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber. Flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was used to select a homogeneous population of 10,000 live cells. The geometrical mean of ethidium fluorescence intensity (excitation 488 nm, emission 610 nm) in the population was used for analysis.

In a separate experiment, HAAECs were cultured using chamber slide and treated with ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min and 48 h separately in the presence and absence of L-NAME. Cells were then treated with DHE (10 μm) for 30 min at 37 C. Ethidium fluorescence images were examined by a fluorescence microscopy (Nikon TE2000-E; Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). As a positive control, angiotensin II (AngII) (100 nm) was used to confirm that the HAAECs were responsive to Nox1 activator.

Effects of ET1 on intracellular ROS production in HAAECs

Intracellular ROS level was assessed as follows. HAAECs were incubated with 1× Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 5 μm 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCFH-DA) in the dark for 10 min. Cells were treated with L-NAME 1 h before exposure to DCFH-DA. After the DCFH-DA incubation, cells were treated with ET1 for 20 min. Fluorescent images were captured using a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Western blot analysis of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 in HAAECs

The procedure for Western blotting was described in our previous studies (20,21). Briefly, the membranes were incubated with antibodies against Nox1 (1:750; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), Nox2 (1:1000, BD Transduction Laboratories; BD Biosciences), and Nox4 (1:750; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 C overnight. The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antigoat, antimouse, and antigoat antibodies (1:2000–1:5000), respectively, for 1 h at room temperature. Target protein expression was normalized with the expression of β-actin, which was served as an internal control.

Effects of ET1 on NADPH oxidase activity and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): role of ETB1 receptors

To test the role of ETB1 receptors in mediating the effect of ET1 on NADPH oxidase activity and cell proliferation, ETB1 receptors were silenced by transfection of HAAECs with small interfering RNA (siRNA) against ETB1 receptors (ETB1siRNA) before treatment with ET1. Human ETB1 (accession no. NM_000115) siRNA was designed, synthesized, and annealed by Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-39962). The scrambled siRNA (catalog no. sc-36869) was used as a control siRNA (ControlsiRNA). The ControlsiRNA was proved, by Santa Cruz Biotechnology, not to match any known gene sequence. In brief, cells were incubated with 60 pmol ETB1siRNA or ControlsiRNA mixed with Oligofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). After 8 h transfection, the medium was refreshed, and the cells were incubated with or without ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min. NADPH oxidase activity was measured using lucigenin as described previously (22). PCNA was measured by Western blot using anti-PCNA antibody (1:5000; Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK).

Effects of RNA interference (RNAi) inhibition of Nox1 on ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity

To determine if Nox1 mediates ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity, Nox1 was silenced by transfection of HAAECs with Nox1 siRNA before treatment with ET1. Human Nox1 (accession no. NM_007052) siRNA was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-43939). Briefly, cells were incubated with 60 pmol ETB1siRNAor ControlsiRNA for 8 h. The medium was refreshed, and the cells were then incubated with or without ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min. NADPH oxidase activity was measured using lucigenin.

Effects of ET1 on intracellular NO levels

Intracellular NO was measured as described earlier (23). Briefly, cells were incubated with a DAF-2DA (10 μm; Peninsula Laboratory Inc., San Carlos, CA) in the presence of 3 mm l-arginine for 30 min at 37 C in the dark in a 5% CO2 in humidified chamber. DAF-2DA was excited at a wavelength of 490 nm, and the emitted fluorescence at a wavelength of 515 nm was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (Synergy 2; BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT).

Because nitric oxide synthase (NOS) generates ROS instead of NO in the absence of l-arginine (24), we added an excess concentration of l-arginine (3 mm) to all solutions used for NO measurement, except for cells treated with L-NAME (0.1 mm), which was added during the last 30 min of the DAF-2DA incubation period. NOS activity was measured in real time using the NO-specific fluorescence probe DAF-2DA in the presence of l-arginine as described by Govers et al. (25).

Intracellular Ca2+ assay

Intracellular calcium levels were measured as described previously (26). Subconfluent HAAECs were loaded with 5 μm/liter Fura-2-AM for 30 min at 37 C in Ringer buffer. Changes in the fluorescence emission were monitored using a fluorescence microplate reader at 37 C, with excitation wavelengths at 340 and 380 nm and an emission wavelength at 500 nm. For details, refer to the supplemental methods, which are published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Effects of ET1 and AG-17 on phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1: role of ETB1 receptors

To determine the effect of ET1 on the activity of Pyk2 and Rac1, we measured the phosphorylated Pyk2 and Rac1 proteins in HAAECs treated with ET1 (10 nm), AG-17, a Pyk2 inhibitor (500 nm; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), ETB1siRNA (60 pmol), and ETB1siRNA plus ET1, respectively. AG-17 specifically inhibits phosphorylation of tyrosine 402 in pyk2 molecule. The phosphorylated Pyk2 was measured by Western blot using phosphor-specific ant-Pyk2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

The endogenous guanosine 5′-triphosphate-associated form of Rac1 in HAAECs was detected using the Rac/CDC42 Assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology Inc., Lake Placid, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For details, please refer to the supplemental methods.

To evaluate the effect of inhibition of Pyk2 on ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase, NADPH oxidase activity was measured in HAAECs treated with AG-17 (500 nm), followed by ET1.

Effects of ET1 on AngII-induced NADPH oxidase activation and cell proliferation

NADPH oxidase activity and PCNA expression were measured in HAAECs treated with ET1 (10 nm), AngII (100 nm), or ET1 plus AngII. In the latter, cells were treated with ET1 (20 min), followed by AngII.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA or the t test where appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

ET1 decreased superoxide production and intracellular ROS level in HAAECs

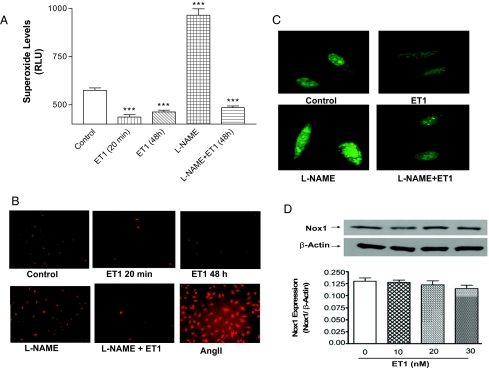

Treatment of HAAECs with ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min significantly decreased superoxide generation compared with untreated cells (control) (Fig. 1, A–C). The ET1-induced decrease in superoxide production was neither dose dependent nor time dependent because no significant difference was found in HAAECs incubated with different concentrations of ET1 (10–30 nm) or at different time intervals (20 min, and 24 and 48 h) (figure not shown). Superoxide generation was increased in cells incubated with a NOS inhibitor (L-NAME). ET1 also significantly decreased superoxide levels in cells pretreated with L-NAME (Fig. 1, A and B), excluding the involvement of NOS in the inhibitory effect of ET1 on superoxide generation. AngII resulted in a profound increase in ROS production (Fig. 1B), indicating that the HAAECs responded well to the Nox1 activator. AngII is used as a positive control; the result should not be compared with those of other treatments. The ET1-stimulated intracellular ROS level was evaluated by fluorescence of ROS-sensitive dye DCFH-DA. Confocal fluorescence images showed that the intracellular ROS level was decreased by ET1 (Fig. 1C). Quantitative results of Fig. 1, B and C, were similar to Fig. 1A (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effects of ET1 on superoxide and ROS generation in HAAECs. HAAECs were incubated with ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min and 48 h in the presence and absence of L-NAME, and exposed to the superoxide specific dye DHE for 30 min in the dark. A, Superoxide production (mean ± sem) was assessed by measuring ethidium fluorescence quantitatively using flow cytometry. B, Fluorescent images (superoxide) of HAAECs (ET1 20 min) were captured using Nikon TE 2000 microscopy (×10). C, Confocal fluorescent images (ROS) of HAAECs (ET1 20 min) incubated with DCHF (×40). D, Nox1 expression (mean ± sem) in HAAECs incubated with ET-1 (10–30 nm) for 48 h at different concentration. ***, P < 0.001 vs. control (untreated HAAECs; n = 4). RLU, Relative light unit.

Treatment with ET-1 (10–30 nm) did not affect Nox1 protein expression (Fig. 1D) in HAAECs. Nox2 or Nox4 protein expression was not detectable in control cells or cells treated with ET-1, indicating that Nox2 and Nox4 are not expressed in HAAECs (figures not shown).

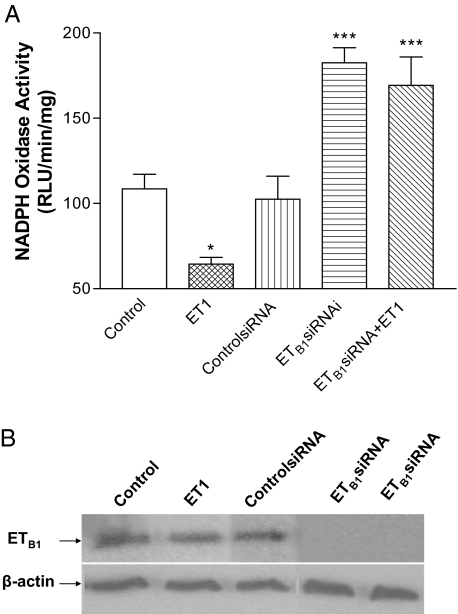

RNAi knockdown of ETB1 receptor abolished ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity

ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity significantly compared with the control (untreated) cells (Fig. 2A). To determine the role of ETB1 receptors in ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity, we evaluated the effect of RNAi inhibition of ETB1 receptors on NADPH oxidase activity. ETB1siRNA completely knocked down ETB1 receptor protein expression (Fig. 2B), indicating effective silence of ETB1 receptors. siRNA did not affect NADPH oxidase, as evidenced by the fact that NADPH oxidase activity was not altered by ControlsiRNA (Fig. 2A). RNAi knockdown of ETB1 receptors resulted in a significant increase in NADPH oxidase activity compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2A), suggesting that ETB1 has tonic inhibition on NADPH oxidase activity. ET1 failed to decrease NADPH oxidase activity in cells pretreated with ETB1siRNA, suggesting that ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity was mediated by ETB1 receptors.

Figure 2.

Effects of ET1 on NADPH oxidase activity: role of ETB1 receptor. A, NADPH oxidase activity (mean ± sem) was measured in HAAECs treated with ET1 or ETB1siRNA, followed by incubation with ET1 (10 nm) for 20 min. B, Western blot analysis of ETB1 receptor protein in HAAECs treated with ET1, ControlsiRNA, and ETB1siRNA. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control (n = 4). RLU, Relative light unit.

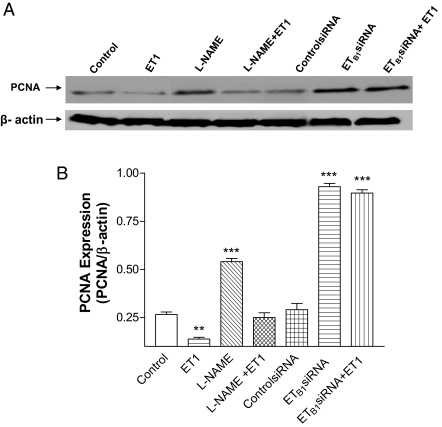

RNAi knockdown of ETB1 receptors abolished ET1-induced inhibition of PCNA expression

To evaluate the role of ET1/ETB1 in cell proliferation, PCNA was measured. ET1 significantly decreased PCNA expression (Fig. 3). Inhibition of NOS by L-NAME increased PCNA significantly, which was abolished by ET1. RNAi inhibition of ETB1 receptor significantly increased PCNA. ET1 failed to decrease PCNA in HAAECs when ETB1 receptors were silenced (Fig. 3B), indicating that ET1-induced inhibition of PCNA expression was mediated by ETB1 receptors.

Figure 3.

Effects of ET1 on PCNA in HAAECs. A, The representative Western blot band of PCNA expression. B, The PCNA to β-actin ratio (mean ± sem) in HAAECs treated with ET1, L-NAME, and ETB1siRNA. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control (n = 3).

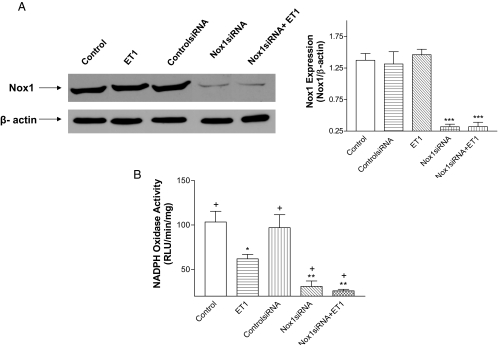

RNAi inhibition of Nox1 abolished ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity

Nox1 siRNA significantly decreased Nox1 protein expression, indicating effective silence of Nox1 (Fig. 4A). Nox1 siRNA significantly decreased NADPH oxidase activity and abolished ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity as ET1 failed to decrease NADPH oxidase activity when Nox1 was silenced (Fig. 4B). NADPH oxidase activity was significantly higher in the ET1-treated cells than the Nox1 siRNA-treated cells, indicating that ET1 resulted in a partial inhibition of Nox1 activity.

Figure 4.

Effect of RNAi inhibition of Nox1 on ET1-induced inhibition in NADPH oxidase activity. Nox1 protein expression (A) and NADPH oxidase activity (B) in HAAECs with different treatments as designated in the figure. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control; +, P < 0.01 compared with cells treated with ET1 (n = 3). RLU, Relative light unit.

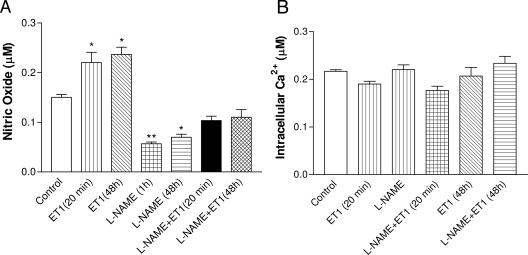

ET-1 enhanced bioavailability of intracellular NO but failed to alter intracellular Ca2+

DAF-2DA fluorescence intensity was used to assess intracellular NO levels. ET1 increased intracellular NO in HAAECs at both 20 min and 48 h after treatment (Fig. 5A). L-NAME completely inhibited NOS activity and decreased NO to a minimal level. ET1 increased NO bioavailability in L-NAME-treated cells to a level that was not significantly different from the control. ET1 increased NO bioavailability when NOS was inhibited, probably due to its inhibitory effect on superoxide production. A decrease in superoxide production can decrease deactivation of NO by superoxide and, thus, increase NO bioavailability relatively.

Figure 5.

A, Effect of ET-1 on intracellular NO and calcium levels. Intracellular NO level in HAAECs measured using DAF-2DA. B, Intracellular calcium levels in HAAECs measured using Fura-2. The values are mean ± sem (n = 4). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs. control cells.

Neither L-NAME nor ET1 affected intracellular Ca2+ level significantly (Fig. 5B).

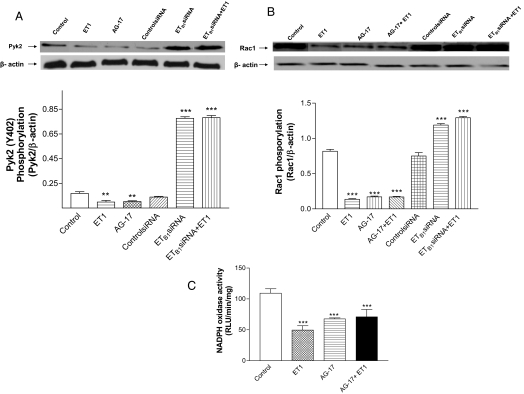

ET1 inhibited phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1: a new ETB1-Pyk2-Rac1 pathway

To explore the relation of ETB1, Pyk2, and Rac1 in HAAECs, we examined Pyk2 and Rac1 activity in the presence and absence of ET1, Pyk2 inhibitor AG-17, and ETB1siRNA. ET1 decreased phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1 (Fig. 6, A and B), indicating that ET1 inhibited the activity of Pyk2 and Rac1. AG-17, a Pyk2 inhibitor, inhibited phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1, and abolished ET1-induced inhibition of Rac1, suggesting that Pyk2 is an upstream regulator of Rac1 activation. RNAi knockdown of ETB1 resulted in significant increases in the activities of Pyk2 and Rac1, and abolished ET1-induced inhibition of the activities of Pyk2 and Rac1 (Fig. 6, A and B). These findings suggest that ETB1 receptors play a critical role in the regulation of the activity of the Pyk2-Rac1 pathway in HAAECs.

Figure 6.

Effect of ET1 on tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1 in HAAECs: role of ETB1 receptors. Phosphorylation of Pyk2 (A), Rac1 (B), and NADPH oxidase activity (C) in HAAECs treated with ET1, AG-17, ETB1siRNA, or ETB1siRNA plus ET1. Phosphorylated Pyk2 and Rac1 were measured using Western blot analysis. The values are mean ± sem (n = 3). **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control cells. RLU, Relative light unit.

Both ET1 and AG-17 decreased NADPH oxidase activity to a similar extent in HAAECs (Fig. 6C). ET1 failed to decrease NADPH oxidase activity when Pyk2 was inhibited by AG-17, indicating that ET1-induced inhibition of Nox1 activity was fully mediated by the Pyk2-Rac1 pathway.

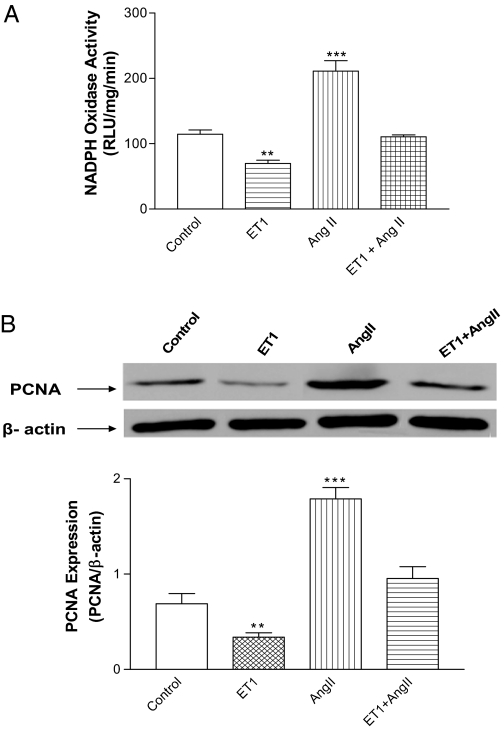

ET1 abolished AngII-induced NADPH oxidase activation and cell proliferation

AngII increased NADPH oxidase activity and PCNA (Fig. 7), suggesting that HAAECs responded well to Nox1 stimulator. ET1 abolished the AngII-induced increase in NADPH oxidase activity and PCNA.

Figure 7.

Effect of ET1 on AngII-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and increase in PCNA. NADPH oxidase activity (A) and PCNA (B) in HAAECs treated with ET1, AngII, and ET1 plus AngII. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control (n = 3). RLU, Relative light unit.

Discussion

The major finding of this study was that ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide generation, and cell proliferation in HAAECs. These effects were apparently mediated by ETB1 receptors because they were abolished by RNAi knockdown of ETB1 receptors. Thus, this study discovered a new function of ETB1 receptors in regulating NADPH oxidase activity in HAAECs. This finding is in sharp contrast with the effect of ET1 in other types of cells such as VSMCs, where ET1 activates NADPH oxidases and increases superoxide production and cell proliferation via ETA and ETB2 receptors (1,6,7,14,27). The present study demonstrated that Nox1 is the predominant NADPH oxidase in HAAECs because RNAi knockdown of Nox1 decreased NADPH oxidase activity to a minimal level. Notably, Nox1 seems to be the sole NADPH oxidase that mediated ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity and superoxide generation, as evidenced by the fact that silence of Nox1 abolished the ET1-induced decrease in NADPH oxidase activity. In addition, ET1 did not activate NADPH oxidase in HAAECs because ET1 did not increase NADPH oxidase activity when Nox1 is silenced. Expression of gp91phox was not found in HAAECs, although it was expressed in bovine and rat endothelial cells (28,29).

The effect of ET1 on NADPH oxidase depends on cell type and developmental stages (1). Activation of ETA or ETB (ETB2) receptors in smooth muscle cells by ET1 stimulates NADPH oxidases and increases superoxide production (1,6,7,14,27). ET1 was reported to stimulate NADPH oxidase and increase ROS production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (30), a defensive process that protects the fetus from microbial invasion. The present study demonstrates that ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity and superoxide production in HAAECs. In addition, the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity probably occurred at the functional (activity) level of Nox1 because ET1 did not alter Nox1 protein expression. This is, to our knowledge, the first report showing that activation of endothelial ETB1 receptors leads to an inhibition of NADPH oxidase. Actually, ETB1 receptors may have tonic inhibition of NADPH oxidase in HAAECs because knockdown of ETB1 resulted in increased NADPH oxidase activity. Thus, ET1/ETB1 may protect endothelial cells by attenuating intracellular ROS level. This novel finding could change our concept regarding the role of ET1 in regulating endothelial function. The endothelial effects of ET1 (i.e. inhibit superoxide generation and stimulate NO release) may mitigate its vasoconstrictor effect in smooth muscle cells in maintaining normal vascular tone and homeostasis. However, vascular ETB1 receptors are down-regulated in hypertension such as cold-induced hypertension and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (31,32). In this condition, endothelial ETB1-induced vasodilation no longer compensates for the direct ET vasoconstrictor effect mediated by ETA and ETB2 receptors in VSMCs (4). In DOCA-induced hypertension, ET1 stimulated vascular NADPH oxidase via ETA and increased superoxide production, resulting in endothelial dysfunction (14). Thus, it is worthwhile to test if endothelial-specific overexpression of ETB1 receptors can be a potential therapeutic approach for endothelial dysfunction in hypertension.

The protective actions of ET1/ETB1 in endothelial cells also include the release of NO and prostaglandins (1,4). Indeed, ET1 enhanced the bioavailability of NO in HAAECs. However, the ET1-induced decrease in superoxide generation was due to its direct inhibition on Nox1, not its stimulating effect on endothelial NOS, because ET1 decreased NADPH oxidase activity and superoxide generation when NOS was inhibited. AngII is a stimulator of Nox1 (11,33). Nox1 is involved in AngII-induced oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and hypertension (10). Actually, AngII stimulates the production of both ET1 and ROS, which mediate AngII-induced hypertension (34). On the other hand, ET1 via ETB1 can inhibit Nox1 and attenuate intracellular ROS production in endothelial cells, which could serve as a compensatory mechanism to attenuate AngII-induced endothelial damage. Thus, the present study suggested, for the first time, that ET1/ETB1 may attenuate AngII-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and superoxide generation in endothelial cells.

PCNA is involved in DNA replication and is necessary for adequate leading strand synthesis, acting as the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase δ (35,36). Thus, PCNA has been used as a marker for cells actively replicating DNA. ET1 inhibited PCNA, which could be abolished by RNAi silence of ETB1, suggesting that ET1 may suppress HAAEC proliferation via ETB1 receptors. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis. NO plays a role in endothelial cell proliferation (37). However, the present study demonstrated increased cell proliferation when NO production was decreased by L-NAME. This is probably due to the relative increase in superoxide level owing to the decreased NO production. Superoxide or ROS can increase DNA replication and cell proliferation (38,39).

Activation of classical GPCRs results in generation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, which elevates intracellular Ca2+ levels (15). However, ET1 failed to alter intracellular Ca2+ level, excluding the possible involvement of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-Ca2+ pathway in inhibiting Nox1 in HAAECs. The effect of ET1 on NADPH oxidase varies with cell types, depending upon subtypes of ET receptors (1). ET1 is known to activate Pyk2 in cardiomyocytes via ETA (16). Pyk2 activates Rac1, leading to the activation of NADPH oxidase (16). The present study demonstrated that ET1 inhibited Pyk2 and Rac1 activity in HAAECs, suggesting that endothelial ETB1 receptors are inhibitory GPCRs. ETB1 receptors may play a crucial role in regulating the activity of Pyk2-Rac1 pathway in endothelial cells, as evidenced by the fact that ETB1 silence increased phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1, and abolished ET1-induced inhibition in phosphorylation of Pyk2 and Rac1. The present study also demonstrated that Pyk2 may be a critical upstream activator of Rac1 activation because inhibition of Pyk2 by AG-17 inhibited phosphorylation of Rac1 and abolished ET1-induced inhibition of phosphorylation of Rac1. Activation of Nox1 requires the activation (phosphorylation) of Rac1, which binds to the complex of NoxO1 (Nox organizer) and NoxA1 (Nox activator) to regulate Nox1 activity and ROS generation (17). Rac1 is the key regulatory subunit for Nox1 activity (17,18). Thus, the present study revealed a new pathway that mediates ET1-induced inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity in endothelial cells: ET1 → ETB1↑ → Pyk2↓ → Rac1↓ → Nox1↓ → NADPH oxidase activity↓. Notably, the inhibitory effect of ET1/ETB1 on Nox1 may be fully mediated by the Pyk2-Rac1 pathway in HAAECs because inhibition of Pyk2 by AG-17 decreased Rac1 and Nox1 activity to the same extents as ET1 did, and abolished ET1-induced suppression of Nox1 activity.

In summary, ET1 inhibited NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide generation, and cell proliferation in HAAECs via ETB1 receptors. The inhibitory effect of ET1 on NADPH oxidase activity was fully mediated by the ETB1-Pyk2-Rac1-Nox1 pathway. ET1 abolished AngII-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and cell proliferation. Thus, this study demonstrated a novel function of ETB1 receptors in protecting endothelial cells, i.e. inhibiting Nox1-dependent NADPH oxidase and superoxide generation. Further studies are needed to validate the findings in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NHLBI 077490 (to Z.S.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online June 5, 2008

Abbreviations: AngII, Angiotensin II; ControlsiRNA, control small interfering RNA; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein; DHE, dihydroethidium; DOCA, deoxycorticosterone acetate; ET, endothelin; ETB1siRNA, small interfering RNA against endothelin B1 receptors; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; HAAEC, human abdominal aortic endothelial cell; L-NAME, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Pyk2, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2; RNAi, RNA interference; ROS, reactive oxygen species; siRNA, small interfering RNA; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

References

- Dammanahalli KJ, Sun Z 2008 Endothelins and NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35:2–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyamala V, Moulthrop TH, Stratton-Thomas J, Tekamp-Olson P 1994 Two distinct human endothelin B receptors generated by alternative splicing from a single gene. Cell Mol Biol Res 40:285–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T 1990 Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature 348:732–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Sudano I, Magagna A, Salvetti A 2001 Role of endothelin in the control of peripheral vascular tone in human hypertension. Heart Fail Rev 6:277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchengast M, Luz M 2005 Endothelin receptor antagonists: clinical realities and future directions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 45:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedgwood S, Dettman RW, Black SM 2001 ET-1 stimulates pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation via induction of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281:L1058–L1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Watts SW, Banes AK, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Chen AF 2003 NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide augments endothelin-1-induced venoconstriction in mineralocorticoid hypertension. Hypertension 42:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts SW, Fink GD, Northcott CA, Galligan JJ 2002 Endothelin-1-induced venous contraction is maintained in DOCA-salt hypertension; studies with receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol 137:69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Harrison DG 2000 Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 87:840–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno K, Yamada H, Iwata K, Jin D, Katsuyama M, Matsuki M, Takai S, Yamanishi K, Miyazaki M, Matsubara H, Yabe-Nishimura C 2005 Nox1 is involved in angiotensin II-induced hypertension: a study in Nox1 deficient mice. Circulation 112:2677–2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Szocs K, Yin Q, Akers M, Zhang Y, Grant SL, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK 2001 Novel gp91(phox) homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells: nox1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ Res 88:888–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassègue B, Clempus RE 2003 Vascular NAD(P)H oxidases: specific features, expression, and regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285:R277–R297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JS, Lariviere R, Schiffrin EL 1994 Effect of a nonselective endothelin antagonist on vascular remodeling in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Evidence for a role of endothelin in vascular hypertrophy. Hypertension 24:183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Fink GD, Watts SW, Northcott CA, Chen A 2003 Endothelin-1 increases vascular superoxide via endothelin (A)-NADPH oxidase pathway in low-renin hypertension. Circulation 107:1053–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson MS, Osanai T, Dunn MJ 1990 Endothelin isopeptides evoke Ca2+ signaling and oscillations of cytosolic free [Ca2+] in human mesangial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1055:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani S, Higuchi Y, Nishida K, Nakayama H, Yamaguchi O, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Kashiwase K, Watanabe T, Asahi M, Taniike M, Tsujimoto I, Matsumura Y, Sasaki T, Hori M, Otsu K 2004 Ca(2+)-sensitive tyrosine kinase Pyk2/CAK β-dependent signaling is essential for G-protein-coupled receptor agonist-induced hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36:799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama T, Geiszt M, Leto TL 2006 Involvement of Rac1 in activation of multicomponent Nox1- and Nox3-based NADPH oxidases. Mol Cell Biol 26:2160–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyano K, Sumimoto H 2007 Role of the small GTPase Rac in p22phox-dependent NADPH oxidases. Biochimie 89:1133–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Jr FJ, Gutterman DD, Rios CD, Heistad DD, Davidson BL 1998 Superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle contributes to oxidative stress and impaired relaxation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res 82:1298–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roufai MB, Li H, Sun Z 2007 Heart-specific inhibition of protooncogene c-myc attenuates cold-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Gene Ther 14:1406–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cade R, Sun Z 2005 Expression of human eNOS in cardiac and endothelial cells. Methods Mol Med 112:91–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung AB, Griendling KK, Lambeth JD 1999 Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase MOX1. Nature 401:79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura C, Oike M, Ohnaka K, Nose Y, Ito Y 2004 Constitutive nitric oxide production in bovine aortic and brain microvascular endothelial cells: a comparative study. J Physiol 554(Pt 3):721–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer B, John M, Heizzel B, Werner ER, Wachter H, Schultz G, Bohme E 1991 Brain nitric oxide synthase is a biopterin- and flavin-containing multi-functional oxido-reductase. FEBS Lett 277:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govers R, Bevers L, Bree PD, Rabelink TJ 2002 Endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity is linked to its presence at cell-cell contacts. Biochem J 361(Pt 2):193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Zmijewski JW, Takabe W, Umezu-Goto M, Le Goffe C, Sekine A, Landar A, Watanabe A, Aoki J, Arai H, Kodama T, Murphy MP, Kalyanaraman R, Darley-Usmar VM, Noguchi N 2006 Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by lysophosphatidylcholine-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 168:1737–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich D, Skopec J, Diederich A, Dai FX 1994 Endothelial dysfunction in mesenteric resistance arteries of diabetic rats: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol 266(3 Pt 2):H1153–H1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Shah AM 2002 Intracellular localization and preassembly of the NADPH oxidase complex in cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 277:19952–19960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktutan U, Draper N, Lang D, Shah AM 1998 Expression of functional neutrophil-type NADPH oxidase in cultured rat coronary microvascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 38:256–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Zhang X, Wold LE, Ren Q, Zhang Z, Ren J 2005 Endothelin-1 enhances oxidative stress, cell proliferation and reduces apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: role of ETB receptor, NADPH oxidase and caveolin-1. Br J Pharmacol 145:323–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GF, Sun Z 2006 Effects of chronic cold exposure on the endothelin system. J Appl Physiol 100:1719–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault T, Coceani F 2003 Endothelin in the perinatal circulation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 81:644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingler K, Wunsch S, Kreutz R, Rothermund L, Paul M, Schmidt HH 2001 Upregulation of the vascular NAD(P)H-oxidase isoforms Nox1 and Nox4 by the renin-angiotensin system in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 31:1456–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock DM 2005 Endothelin, angiotensin, and oxidative stress in hypertension. Hypertension 45:477–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G, Tan CK, Kostura M, Mathews M, So AG, Downey KM, Stillman B 1987 Functional identity of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and DNA polymerase-δ auxiliary protein. Nature 326:517–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo R, Frank R, Blundell PA, Macdonald-Bravo H 1987 Cyclin-PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-δ. Nature 326:515–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke JP 2003 NO and angiogenesis. Atheroscler Suppl 4:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gines JA, Lopez-Ongil S, Gonzalez-Rubio M, Gonzalez-Santiago L, Rodriguez-Puyol M, Rodriguez-Puyol D 2000 Reactive oxygen species induce proliferation of bovine aortic endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 35:109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milovanova T, Chatterjee S, Manevich Y, Kotelnkova I, Debolt K, Madesh M, Moore JS, Fisher AB 2006 Lung endothelial cell proliferation with decreased shear stress is mediated by reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290:C66–C76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.