Abstract

During pregnancy, the muscular layer of the uterine wall known as the myometrium, which is composed mainly of smooth muscle cells, is maintained in a state of relative quiescence. A switch from myometrial quiescence to myometrial activation is required to establish uterine contractions during labor. Researchers have long been perplexed by the fact that the major prostaglandin produced by the uterus just prior to labor, prostacyclin, is a smooth muscle relaxant. In this issue of the JCI, Fetalvero et al. provide data that they propose explains this paradox, at least in part (see the related article beginning on page 3966). The authors examined uterine tissue from pregnant women near term and found that prostacyclin stimulation, which raises cAMP levels that were previously thought to affect only myometrial quiescence, can promote myometrial activation over time by increasing the expression of a select group of proteins thought to be indicative of a uterine contractile state.

For human childbirth to proceed in an efficient and timely fashion, there has to be at least one process whereby the periodicity and strength of laboring uterine contractions are discretely regulated. Although our understanding of the minutiae of uterine signaling mechanisms remains rather rudimentary, pregnancy is now often described as a quiescent state that must therefore become activated. This has focused attention on 2 issues: how myometrial relaxant signaling pathways, principally those mediated by adenylyl cyclase/cAMP/PKA signaling (1), might be switched off, and how contraction-associated signaling pathways may be switched on. Proinflammatory cytokine stimulation linked to prostaglandin production is often suggested to be a contributor to the latter (2, 3). The study by Fetalvero et al. reported in this issue of the JCI introduces more complexity to these considerations: these authors offer the radical notion that uterine production of the prostaglandin prostacyclin, previously widely held as a smooth muscle relaxant, actually increases expression of procontractile factors in a cAMP/PKA-dependent manner (4).

Prostacyclin as a myometrial stimulant

In their current study, Fetalvero et al. pursued the possibility that prostacyclin may stimulate procontractile transcriptional/translational events in human myometrium, buoyed by long-known data suggesting that prostacyclin may be the most abundant myometrial prostaglandin increased with pregnancy and/or labor (ref. 4 and references therein). The authors used organ-cultured human uterine tissue strips obtained from pregnant women undergoing Caesarean delivery prior to the onset of natural labor or passaged cells cultured from human uterine tissue. Following incubation with or without the synthetic prostacyclin analog and human prostacyclin receptor (hIP) agonist iloprost, or a hIP antagonist, they measured the degree of contractions induced by the uterine smooth muscle contractant oxytocin as well as specific myometrial gene and protein changes. The authors concluded that hIP activation upregulates the expression of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoform 2 (SM2-MHC), h-caldesmon, calponin, and α-SMA as well as the gap junctional protein connexin 43 and that this upregulation was indeed controlled by a hIP-mediated cAMP/PKA signaling axis. Furthermore, they suggest that this regulation results in enhanced myometrial tissue responsiveness to the major in vivo uterine smooth muscle contractant, oxytocin.

Prostacyclin signaling via cAMP and PKA

The findings of the current study and bold claims made by the authors (4) will generate considerable interest and scrutiny, as they will likely be viewed by many as contentious. The major conundrum surrounding the data reported in this study, with respect to the mechanistic implications for uterine contraction, regards the authors’ proposition that stimulation of a cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling pathway, almost universally regarded as having a prorelaxant effect on the myometrium, may actually have the countereffect of eventually facilitating myometrial contraction. An issue key to the current study is how myometrial hIP/PKA signaling may effect changes in the expression of SM2-MHC, h-caldesmon, calponin, α-SMA, and connexin 43. However, cAMP elevation instigates a wide variety of transcriptional events in many cells and tissue types, including myometrium (5). Given the pleiotropic nature of such cAMP-mediated regulation, one wonders whether other receptor-coupled stimuli (e.g., β-adrenergic agonists, prostaglandin E2, etc.) or pharmacological agents (e.g., forskolin) will elicit the same outcomes as outlined here by Fetalvero et al. (4). Similarly, the expression of a wide variety of proteins would be expected to be changed by procedures that raise cAMP, not just the few focused on in the current study. In this regard, it will be crucial in future studies to determine any specific impact of prostacyclin that is separate from the influence of other cAMP stimulants.

Some additional concerns will also have to be addressed in future investigations. The present study is heavily reliant on the use of hIP pharmacological agonists and antagonists (4), yet no data are provided regarding hIP expression in the uterine samples used, and little is known regarding hIP expression in uterine tissues in general (6). Therefore, there is a need to revisit the issues of how, when, and where a rise in prostacyclin expression occurs. Given the reportedly short half-life of prostacyclin, are the major sites of prostacyclin production (which include the amnion, decidua, and endothelial cells) likely to affect a sufficient number of distant, hIP-expressing myometrial cells? This is a question we need to consider when discussing any endocrine/paracrine/autocrine agent suggested to be an in vivo myometrial stimulant, including the proinflammatory agents suggested by many others to be procontractile (2, 3).

Furthermore, although the authors report that hIP stimulation with iloprost induced an enhanced contractile response to oxytocin, they did not investigate the effect of iloprost on spontaneous contractility, and the sensitivity to oxytocin was not examined (4). It would also be interesting to determine in these model systems whether hIP stimulation alters the expression of alternative isoforms of myosin heavy chain, actin, and caldesmon that may predominate in nonmuscle cells. We also must not overlook the fact that h-caldesmon and calponin, referred to by the authors as contractile proteins, have been previously reported to exert inhibitory effects on actomyosin interaction — the system of actin and myosin filaments responsible for muscle cell contraction (7, 8).

Prostacyclin signaling via cAMP-dependent transcription factors

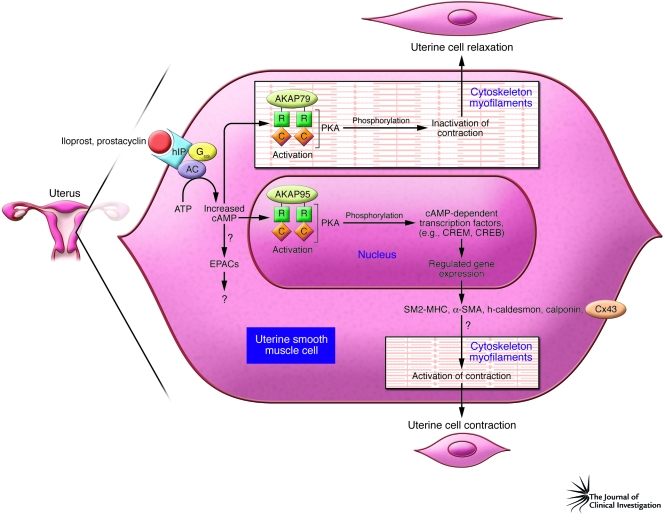

In uterine cells, PKA-mediated transcriptional events involve phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factors cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB) and/or cAMP response element–modulator protein (CREM) that then bind to cAMP response elements in particular genes (Figure 1 and refs. 5, 9). Receptor-coupled stimulation of Gαs, the subunit coupled to hIP, elicits this response, yet myometrial Gαs levels are downregulated at term (10). So will hIP stimulation enact transcriptional changes via Gαs/PKA-dependent CREB and/or CREM phosphorylation (Figure 1)? If so, how can it be that the same control points in this signaling pathway exert different outcomes in terms of the ability to increase the expression of proteins that promote contraction as well as the expression of those proteins that may effect relaxation?

Figure 1. Possible pathways of prostacyclin-mediated stimulation of cAMP and myometrial activation.

Receptor-coupled Gαs stimulation of myometrial adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity raises intracellular cAMP levels. Prostacyclin, or hIP agonist iloprost, act via this route. cAMP is traditionally thought to set in operation a cascade involving activation of PKA bound to anchoring proteins (e.g., AKAP79), release of PKA catalytic subunits (C) from regulatory RIIβ subunits (R), and subsequent phosphorylation of intracellular proteins that effect myometrial relaxation and quiescence. An additional longer-term effect of Gαs-dependent cAMP elevation is promotion of the expression of genes encoding proteins with relaxant influences. Normally, Gαs stimulation of cAMP levels would alter gene expression via nuclear PKA (possibly bound to AKAP95) stimulation and subsequent activation of cAMP-dependent transcription factors, such as CREB and CREM. The report by Fetalvero et al. in this issue of the JCI (4) challenges the latter theory by suggesting that the Gαs-coupled receptor hIP actually induces, by raising cAMP levels, the positive transcription of genes encoding several proteins that are more associated with uterine activation prior to labor: SM2-MHC, h-caldesmon, α-SMA, calponin, and connexin 43 (Cx43). It remains to be determined whether hIP alteration of myometrial expression of these genes occurs via the cAMP-dependent transcription factors CREB and CREM. An alternative possibility may be for hIP (and other stimuli that raise cAMP levels) to activate another class of cAMP-responsive transducing molecules known as exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (EPACs). Their role in human myometrium, and myometrial prostacyclin-dependent signaling pathways, remains to be resolved.

Clinical relevance of the new data

Based on the data presented in their study, Fetalvero et al. (4) speculate that that their observations have important implications with respect to our understanding of myometrial activation, and hence clinical trials of prostacyclin-based therapeutics in pregnancy are warranted because they may lead to better strategies to induce labor or prevent preterm labor (PTL). PTL is the most serious pregnancy complication in developed countries and an important precedent of chronic disability. However, the authors’ suggestion is premature for several reasons. First, PTL rates have remained resistant to broadly effective clinical intervention (11). This is evidence enough to caution against new clinical trials when we know insufficient details about uterine mechanisms of prostacyclin action. Second, the reported outcomes of previous trials of tocolysis — the delay or inhibition of labor during the birth process — with β-adrenergic agonists (agents that raise cAMP levels) are pertinent (12). Multiple studies have shown that β-adrenergic agents were efficacious in reducing uterine contractions and prolonging gestation for 48–72 hours, but without improvement in newborn outcomes, and these drugs have largely been abandoned because of serious, potentially fatal maternal and fetal/neonatal side effects (13). There was no evidence of uterine activation, and women receiving full therapeutic doses of β-adrenergic drugs had no greater chance of early delivery than did those who received the placebo treatment. This suggests that stimulation of the adenylyl cyclase/cAMP/PKA signaling system in vivo, at least by β-adrenergic stimulation of cAMP, does not cause uterine activation.

Multiple control points of myometrial adenylyl cyclase/cAMP/PKA signaling

These issues aside, the theory that a straightforward inversion between quiescent and activating signaling pathways controls the onset and maintenance of uterine laboring contractility is likely to be an oversimplification. A generally emerging notion is that regulation of spatiotemporal signal transduction dynamics is an important means of cellular information processing and transfer. Such spatiotemporal phenomena are likely to add functionality to cell information processing by enabling signals to be encoded in frequency, amplitude, and space. This can occur rapidly (in milliseconds) or slowly (e.g., circadian responses over 24 hours) and within a single cell and between cellular systems (14–17). Furthermore, spatiotemporal signaling diversity can arise at a single-cell or intercellular level with a bewildering complexity for cAMP-based systems (18): the dynamics of cAMP production, maintenance, and localization can be determined by Gαs abundance (10); by adenylyl cyclase isoforms (1); by PKA regulatory and catalytic binding partners, for example, A kinase–anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) and AKAP95 (19, 20); and by phosphodiesterase isoform expression (21). Finally, it is emerging in a number of cellular contexts that another class of cAMP-interacting proteins, exchange proteins activated by cAMP (EPACs), can control diverse signaling processes (18, 22). Therefore, their role in the myometrium needs to be elucidated.

We favor the concept that uterine preparation for labor consists of a plethora of signaling pathways, within and between cells and with distinct spatiotemporal dynamics, being remodeled in parallel. The coordinated uterine contractions will arise when — with facilitation from extraneous stimuli of the uteroplacental environment — enough procontractile pathways enter a spatial and temporal phase with each other. It is a notion we describe as modular accumulating physiological systems (MAPS). This modularity may underlie the difficulty one has achieving sufficient tocolysis once labor has begun. Processes once viewed as system redundancy might, in the context of the human uterus, actually be evidence of the robustness of a fit-for-purpose system, in this case labor (23). It is unclear whether the data reported by Fetalvero et al. (4) supports this idea or merely alludes to it, but there are 2 final curiosities to note: first, there are a number of CREB and/or CREM isoforms with different gene transactivation/repressor actions in the myometrium that are also differentially regulated with pregnancy (9); and second, the promoter regions of genes encoding the archetypal procontractile proteins — connexin 43 and the oxytocin receptor — contain cAMP response elements (9). Is it possible that the particular spatiotemporal mode of myometrial cAMP stimulation will predetermine a range of outcomes in the same cell, tissue, or organ? Will hIP/PKA coupling to downstream transcription factors be another form of MAPS leading to parturition? The jury remains in deliberation. The work reported here by Fetalvero et al. reminds us that signal transduction control of the uterus operates at many more levels of regulation and interaction than is often considered.

Acknowledgments

M.J. Taggart and G.N. Europe-Finner are members of the European Parturition Group. B.F. Mitchell is the recipient of a Newcastle University Research Office Visiting Professorship to Newcastle University.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: AKAP, A kinase–anchoring protein; CREB, cAMP response element–binding protein; CREM, cAMP response element–modulator protein; hIP, human prostacyclin receptor; SM2-MHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoform 2.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 118:3829–3832 (2008). doi:10.1172/JCI37785.

See the related article beginning on page 3966.

References

- 1.Price S.A., Pochun I., Phaneuf S., López Bernal A. Adenylyl cyclase isoforms in pregnant and non-pregnant human myometrium. J. Endocrinol. 2000;164:21–30. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1640021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blank V., Hirsch E., Challis J.R.G., Romero R., Lye S.J. Cytokine signaling, inflammation, innate immunity and preterm labour – a workshop report. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S102–S104. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindström T., Bennett P.R. The role of nuclea factor kappa B in human labour. Reproduction. 2005;130:569–581. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fetalvero K.M., et al. Prostacyclin primes pregnant human myometrium for an enhanced contractile response in parturition. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3966–3979. doi: 10.1172/JCI33800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey J., Tyson-Capper A.J., Gilmore K., Robson S.C., Europe-Finner G.N. Identification of human myometrial target genes of the cAMP pathway: the role of cAMP-response element binding (CREB) and modulator (CREMalpha and CREMtau2alpha) proteins. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;34:1–17. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sooranna S.R., Grigsby P., Myatt L., Bennett P.R., Johnson M.R. Prostanoid receptors in human uterine myocytes: the effect of reproductive state and stretch. Mol. Human Reprod. 2005;12:859–864. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marston S. Calcium ion-dependent regulation of uterine smooth muscle thin filaments by caldesmon. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989;160:252–257. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small J.V., Gimona M. The cytoskeleton of the vertebrate smooth muscle cell. Acta. Physiol. Scand. . 1998;164:341–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey J., et al. Characterisation and functional analysis of cAMP response element modulator protein and activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) isoforms in the human myometrium during pregnancy and labor: identification of a novel ATF2 species with potent transactivation properties. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2002;87:1717–1728. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.4.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Europe-Finner G.N., Phaneuf S., Tolkovsky A.M., Watdon S.P., Lopez Bernal A. Down regulation of Galphas in human myometrium in term and preterm labour: a mechanism for parturition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 1994;79:1835–1839. doi: 10.1210/jc.79.6.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg R.L., Culhane J., Iams J.D., Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray C.J., Lopez A.D. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macones G.A., Berlin M., Berlin J.A. Efficacy of oral beta-agonist maintenance therapy in preterm labor: a meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995;85:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00374-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.[No authors listed.] . Spatiotemporal mechanisms of life [editorial]. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:593. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1007-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buonomano D.V. The biology of time across different scales. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:594–597. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1007-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. . Physiol. Rev. 2004;86:369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sillitoe K., Horton C., Spiller D.G., White M.R. Single-cell time-lapse imaging of the dynamic control of NF-kappaB signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:263–366. doi: 10.1042/BST0350263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarnæss E., Taskén K. Spatiotemporal control of cAMP signalling processes by anchored signalling complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:931–937. doi: 10.1042/BST0350931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku C.Y., Word R.A., Sanborn B.M. Differential expression of protein kinase A, AKAP79, and PP2B in pregnant human myometrial membranes prior to and during labor. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2005;12:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDougall M.W., Europe-Finner G.N., Robson S.C. Human myometrial quiescence and activation during gestation and parturition involve dramatic changes in expression and activity of particulate type II (RII alpha) protein kinase A holoenzyme. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:2194–2205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan W., Lopwz Bernal A. Cyclic AMP signalling pathways in the regulation of uterine relaxation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2007;7:S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-S1-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misra U.K., Pizzo S.V. Coordinate regulation of forskolin-induced cellular proliferation in macrophages by protein kinase A/cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) and Epac1-Rap1 signaling: effects of silencing CREB gene expression on Akt activation. J. Biol. Chem. . 2005;280:38276–38289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noble, D. 2006.The music of life: biology beyond the genome. Oxford University Press. Oxford, United Kingdom. 153 pp. [Google Scholar]