Abstract

Expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue have previously been found to predict pain and fatigue among breast cancer surgery patients. However, the study of predictors of these expectancies has been neglected. The present study was designed to investigate predictors of expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue among breast cancer surgery patients.

Four hundred and eighteen women (M = 48.3 years, SD = 13.66 years) scheduled to undergo excisional breast biopsy or lumpectomy completed questionnaires assessing demographics/medical history, pre-surgical distress, stable personality characteristics, pre-surgical pain and fatigue, and expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue.

Path analysis revealed: expectancies for post-surgical pain were significantly predicted by trait anxiety, acute pre-surgical distress, and age; and expectancies for post-surgical fatigue were significantly predicted by acute pre-surgical distress, acute pre-surgical fatigue, previous experience with the same surgical procedure, and education (all ps < .05). Examination of an alternative model revealed that the effects of the aforementioned predictors on expectancies were not mediated by acute pre-surgical distress, clarifying the directionality of the distress-expectancy relationship.

Expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue are influenced by distress, treatment history, stable personality characteristics, extant symptoms, and demographic factors. These variables should be considered in designing clinical interventions to manipulate expectancies for patient benefit.

Keywords: Response expectancies, Post-surgical pain, Post-surgical fatigue, Distress, Breast cancer surgery

1. Introduction

More than two hundred thousand women in the United States are expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer this year (American Cancer Society, 2006). As part of diagnostic procedures and/or curative treatment, the majority of these women will undergo breast surgery (e.g., excisional breast biopsy, lumpectomy) (Wyatt & Friedman, 1998), which can be an emotionally and physically difficult experience (e.g., Carpenter et al., 1998; Geller, Oppenheimer, Mickey, & Worden, 2004; Stanton & Snider, 1993). Two of the most commonly reported aversive sequelae of breast cancer surgery are pain and fatigue (Geller et al., 2004; Wyatt & Friedman, 1998). Although patients react to surgery and the accompanying anesthesia on a biological level, their experience of pain and fatigue following surgery is complex and multiply determined (Cella, 1998; Loeser & Melzack, 1999; Salmon & Hall, 1997). Literature indicates that response expectancy is one psychological factor that plays an important role in predicting post-surgical pain and fatigue (Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004).

Response expectancies have been described as expectancies about nonvolitional reactions (e.g., physiological symptoms) to events (Kirsch, 1990). For example, women scheduled to undergo breast cancer surgery have specific pre-surgical expectancies about how much post-surgical pain and fatigue they will experience (Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004; Montgomery, Weltz, Seltz, & Bovbjerg, 2002). A recent study found that such treatment-related expectancies are common among cancer patients (Hofman et al., 2004). According to Response Expectancy Theory (Kirsch, 1990), response expectancies are sufficient to cause nonvolitional outcomes. A growing body of research has supported this concept among various surgery patients (Logan & Rose, 2005; Salmon & Hall, 1997; Wallace, 1985), including breast cancer surgery patients (Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2002), as well as in experimental contexts (e.g., Montgomery & Kirsch, 1997; Price et al., 1999). Although the relationship between expectancies and post-surgical side effects has been well established in the literature, little research has been conducted to determine the sources of these expectancies. Therefore, the present study was intended to be one of the first to address this gap in the literature.

One possible predictor of expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue is pre-surgical distress, often experienced by women awaiting curative as well as diagnostic breast surgery (e.g., Benedict, Williams, & Baron, 1994; Deane & Degner, 1998; Montgomery et al., 2003; Poole, 1997). According to Leventhal’s dual process model (Leventhal, Leventhal, & Cameron, 2001), emotional factors can affect cognitive factors. Therefore, one might expect that distress would predict expectancies for pain and fatigue. To our knowledge, only two studies in the literature have empirically tested the relationship between distress and response expectancies, and their findings were contradictory. In an experimental setting, Sullivan, Rodgers, and Kirsch (2001) found that among college undergraduates, prior experience of depressive symptoms was not significantly related to pain expectancies. However, among chemotherapy patients, Montgomery and Bovbjerg (2003) found that emotional distress was a significant predictor of expectations for posttreatment nausea early in the course of repeated outpatient chemotherapy infusions. In view of these mixed findings, one aim of the present study was to investigate whether pre-surgical distress would predict expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue among a sample of breast cancer surgery patients. Furthermore, if a relationship between distress and expectancies were found, an exploratory aim of the present study was to investigate the directionality of this relationship, as it is unclear whether feeling distressed leads one to expect a worse post-surgical recovery, or whether expecting a worse post-surgical recovery causes distress.

A second possible predictor of expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue is stable personality characteristics. For example, individuals’ overall levels of optimism might predict their levels of post-surgical expectancies (Scheier & Carver, 1985). In particular, more optimistic individuals might expect favorable post-surgical outcomes (e.g., lower levels of pain and fatigue), whereas those who are less optimistic might expect more unfavorable post-surgical outcomes (e.g., higher levels of pain and fatigue). Similarly, (Chan & Lovibond, 1996; Spielberger, 1966, 1972) trait anxiety may influence individuals’ response expectancies, such that increased levels of trait anxiety might predict increased expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue.

A third possible source of response expectancies is previous experience (Kirsch, 1990; Rotter, 1982). Although few empirical studies have examined prior experience as a predictor of specific response expectancies, existing literature supports a relationship between the two (Montgomery et al., 2003). In the present study, we hypothesize that expectancies may be shaped by relevant prior personal experiences [i.e., previous breast biopsy, any previous surgery, or having had the scheduled procedure in the past] or by knowing others who have/had breast cancer (i.e., family histories of breast cancer).

A fourth source of response expectancies was suggested by the work of Hofman et al. (2004), which indicates that among cancer patients, levels of pain and fatigue prior to treatment were related to expectancies for pain and fatigue during treatment. Therefore, it was hypothesized that pre-surgical levels of pain and fatigue in our sample would predict expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue.

To investigate these hypotheses, we examined the degree to which expected post-surgical pain and fatigue were predicted by distress, stable personality characteristics, previous experience, and extant symptoms in a sample of breast cancer surgery patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Female patients (N = 418) scheduled for breast conserving surgery (i.e., excisional breast biopsy, lumpectomy) were consecutively recruited and participated in the study. Women under-going these two types of surgery were combined because the two procedures are surgically similar except that the latter requires a greater surgical margin of healthy tissue (DeVita, Hellman, & Rosenberg, 1997). Patients were referred by two breast surgeons in the New York Metropolitan area (69% from one surgeon’s practice, and 31% from the other’s); there was no significant association between surgeon and either of the study outcomes (ps > .10). Participants were included if they were at least 18 years of age and scheduled to undergo breast surgery; and were excluded if they were currently in treatment for a psychiatric illness or were unable to read and understand English.

Participants ranged in age from 19 to 83 years (M = 48.3 years; SD = 13.7 years). Most of the sample (76%) was scheduled for excisional biopsy, and 24% was scheduled for lumpectomy. Regarding ethnicity, 70% of participants described themselves as white (not Hispanic), 12% as black (not Hispanic), 9% as white (Hispanic), 4% as “other,” 3% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and 2% as black (Hispanic). This sample was evenly balanced between individuals who were currently married (49%) and those who were not (51%). The majority of this sample: had attained a college degree (64%), had no family history (first-degree relatives) of breast cancer (89%), and had had some type of surgery in the past (58%). Additionally, most women in the present study had not received a breast biopsy prior to surgery (65%). Following diagnosis, the majority of the participants were found to be cancer negative (70%).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Experience variables

2.2.1.1. Demographics/Medical History Questionnaire

This self-report measure assessed basic demographic information, as well as family history of cancer and prior surgical history.

2.2.1.2. Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain and fatigue

100 mm long visual analog scales were used to assess extant pre-surgical pain and fatigue (“right now”) (Coll, Ameen, & Mead, 2004; Wolfe, 2004), and were administered on the day of surgery, prior to surgery. The anchor points for these scales were “No Pain at All” and “As Much Pain as There Could Be,” and “Not at All Fatigued” and “As Fatigued as I Could Be.”

2.2.2. Stable personality characteristics

2.2.2.1. The Life Orientation Test (LOT) (Scheier & Carver, 1985)

The LOT is an eight item (plus four filler items) measure of dispositional optimism. Higher scores on the measure indicate higher levels of optimism. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the LOT was 0.80.

2.2.2.2. Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale-Short Form (TMAS-SF) (Bendig, 1956)

The TMAS-SF is a shortened form of a widely used measure of trait anxiety (TMAS) (Taylor, 1953). This shortened form consists of 20 true-false questions used to evaluate individual characterological tendencies toward anxiety. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

2.2.3. Distress

2.2.3.1. Profile of Mood States - Short Version (POMS-SV)

This 37-item measure was used to assess level of pre-surgical mood disturbance over the past week (Shacham, 1983). Previous research has found the Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score to have adequate internal consistency and validity (DiLorenzo, Bovbjerg, Montgomery, Jacobsen, & Valdimarsdottir, 1999). In the current research sample, Cronbach’s alpha for TMD was 0.93.

2.2.3.2. Visual Analog Scale (VAS) distress

This item was used to assess acute pre-surgical emotional distress on the morning of surgery, and was identical in format to the VASs for pain and fatigue, except that it asked about emotional upset, and was anchored by “Not at all upset” and “As upset as I could be.” The use of VAS questions has been well supported in previous studies related to breast cancer (e.g., DiLorenzo et al., 1995; Montgomery et al., 2002).

2.2.4. Response expectancies

2.2.4.1. Visual Analog Scales (VAS) expectations

These items have been used in our previous research with this patient population (Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2002), and were identical in format to the other VAS questions, except that they asked patients: (1) “After surgery, how much pain do you think you will feel?” and (2) “After surgery, how fatigued do you expect to be?”.

2.3. Procedure

Immediately following consultation with their surgeon, during which patients received standardized clinical information regarding breast surgery, patients were contacted by study personnel, who described the study and obtained patients’ informed consent. Upon receiving written informed consent, study personnel gave participants a questionnaire packet, and asked them to complete this packet at home prior to their surgery. This takehome packet contained the demographics/medical history questionnaire, POMS-SV, LOT, TMAS, and extant pre-surgical pain and fatigue VASs. On average, patients completed this questionnaire packet 5.33 days prior to surgery. Participants were asked to return this packet on their surgery day (prior to surgery), at which time they were administered an additional questionnaire packet containing the VASs measuring acute pre-surgical distress and expectancies. A research assistant was available to answer any of the participants’ questions about the study materials.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Path analysis was used to assess the relative contribution of pre-surgical distress, stable personality characteristics, past experience, and extant symptom level to the prediction of expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue. Path models were constructed and tested using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation in LISREL 8.72 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2005). Prior to testing path models, exploratory data analysis revealed a number of incomplete cases (i.e., participants missing one or more scores constituted 210 of the 418 participants) among the 15 variables used for the present analyses.

Traditional methods of handling missing data (e.g., listwise deletion or mean imputation) can lead to severely biased results (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Thus, multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987) was used to model the missingness of the data. Specifically, six complete data sets were imputed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo estimation in LISREL as recommended by Schafer (1997). Path estimates reported below represent the average standardized parameter estimate across the six data sets and were computed using rules outlined by Rubin (1987). Multiple group analysis indicated that model fit did not differ across imputations; consequently, mean values for all fit indices are reported.

3. Results

Examination of demographic variables (i.e., age, ethnicity, education, and marital status) revealed a significant negative correlation between age and expected pain (r(416) = -.20, p < .001). Additionally, a significant positive correlation was found between years of education and expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue (ps < .01). Thus, age and years of education were included as predictors of post-surgical expectancies in path analysis models. Other demographic variables were not significantly related to expectancies for post-surgical fatigue or pain (ps > .10) and were excluded from path analysis.

Pre-surgical distress, stable personality characteristics, past experience, and extant pre-surgical pain and fatigue were included in a path analysis model predicting expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue. Specifically, pre-surgical mood disturbance, acute pre-surgical distress, extant pre-surgical fatigue and pain, trait anxiety, trait optimism, past breast biopsy, past surgery, family history of cancer, and having had the same procedure before were hypothesized to predict expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue. Given that no specific hypotheses were made about the relationships between expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue, and given that these variables referred to the same future time point (following surgery), the outcome variables were allowed to covary in all reported path models. The initial path model converged to an adequate solution: , p = .65, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.00, Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) = .002. Although fit indices did not call into question the path model’s goodness-of-fit, closer examination of the parameter estimates indicated that several of the hypothesized predictors (i.e., pre-surgical mood disturbance, optimism, past biopsy experience, past surgery experience) failed to show a significant relationship with expectancies for either post-surgical pain or fatigue (ps > .10). Thus, consistent with trimming the model to provide the most parsimonious solution for the data (Kline, 2005), measures that failed to predict their hypothesized outcome were removed from the model.

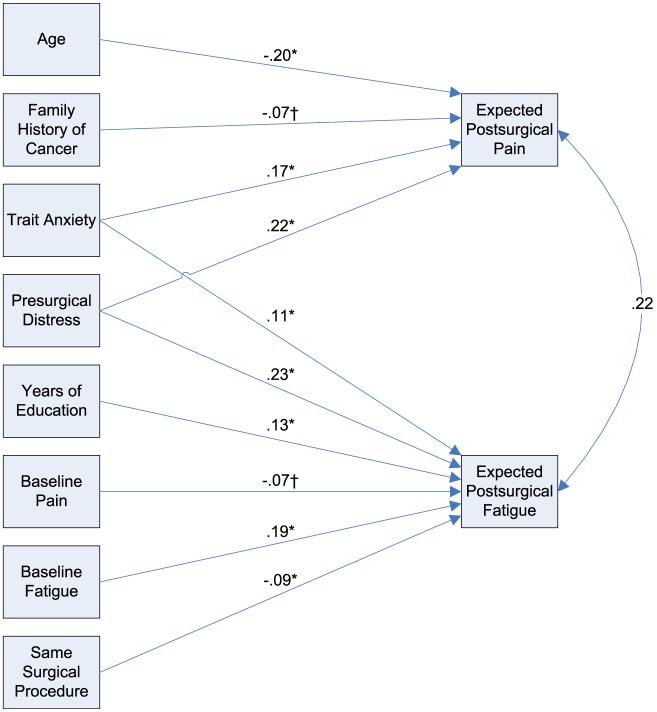

Consequently, in the new model: expectancies for post-surgical pain were predicted by acute pre-surgical distress, family history of cancer, age, and trait anxiety; whereas expectancies for post-surgical fatigue were predicted by acute pre-surgical distress, extant pre-surgical pain, extant pre-surgical fatigue, trait anxiety, having had the same surgical procedure in the past, and years of education (see Fig. 1). The trimmed model provided a good fit to the data: , p = .67; RMSEA = 0.00 (90% Confidence Interval = 0.00-0.05), CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .013. Consistent with study hypotheses, individuals higher in trait anxiety were more likely to expect higher levels of post-surgical pain. Further, acute pre-surgical distress was positively related to expectancies for post-surgical pain, whereas age was negatively related to expectancies for post-surgical pain. Individuals with a family history of breast cancer displayed a trend toward lower post-surgical pain expectancies (p = .07). Together, these predictors accounted for 14% of the variance in patients’ expectancies for post-surgical pain (R2 = .14).

Fig. 1.

Trimmed path model predicting expected post-surgical pain and fatigue. Note: Parameter estimates reflect standardized regression coefficients. *p < .05, †p < .10.

Higher acute pre-surgical distress and fatigue were associated with higher fatigue expectancies (see Fig. 1). Having had the same surgical procedure before was associated with lower expectancies for post-surgical fatigue. Years of education were positively associated with expectancies for post-surgical fatigue; patients’ VAS expectancy ratings were approximately two points higher for each year of education they had completed. Individuals higher in trait anxiety were more likely to experience higher post-surgical fatigue expectancies. There was a trend for patients with higher extant pain to expect lower post-surgical fatigue, although this parameter failed to reach significance (p = .08). 18% of patients’ expectancies for post-surgical fatigue was accounted for by these predictors (R2 = .18).

An exploratory aim of the paper was to investigate the directionality of the relationship between distress and expectancies. Therefore, an alternative model was considered that tested whether acute pre-surgical distress was a function of expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue. This alternative model provided a poor fit to the data: , p < .0001, RMSEA = .13, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = .057. Model fit for the alternative model could not be improved using model trimming techniques.

4. Discussion

Expectancies for treatment-related pain and fatigue are common among cancer patients (Hofman et al., 2004), and contribute to the subsequent experience of these taxing symptoms (Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2002). Results of the present study indicated that: heightened distress on the day of surgery (prior to surgery) as well as heightened trait anxiety predicted higher expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue; having had the same surgical procedure in the past predicted lower expectancies for post-surgical fatigue; and higher levels of acute pre-surgical fatigue predicted higher expectancies for post-surgical fatigue. Overall, each of the hypothesized classes of predictors (distress, stable personality characteristics, past experience, and extant symptom level) was found to contribute to response expectancies for pain and fatigue. Additionally, older individuals were more likely to expect lower post-surgical pain, and more educated individuals were more likely to expect higher post-surgical fatigue.

These results raise two interesting issues. First, within each class of predictors, certain variables predicted expectancies, whereas others did not. In terms of distress, acute pre-surgical distress was found to predict higher expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue, whereas mood disturbance over the past week predicted neither. This suggests that expectancies may be primarily a function of current emotional state. In terms of stable personality characteristics, trait anxiety significantly predicted expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue, whereas trait optimism predicted neither. This difference could be related to the differing specificity of the constructs. Optimism has been defined as a generalized tendency to have positive expectancies for the future (Scheier & Carver, 1985; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994), whereas trait anxiety has been defined in part as a disposition to feel anxious in specific situations, that is, in response to perceived threats. One might therefore expect that trait anxiety, with its more specific nature, would be more closely related to specific symptom expectancies (i.e., pain and fatigue) than a more generalized trait (i.e., optimism); an expectation supported by the present findings. Conversely, on the basis of these findings, one might predict that optimism would be more closely related to more generalized post-surgical expectancies (e.g., “Overall, how well do you expect your recovery to go?”) than trait anxiety. However, because such expectancies were not assessed in this study, the role of optimism in generalized post-surgical expectancies remains an open question. In terms of past experience, having had the same surgical procedure before was predictive of lower expectancies for post-surgical fatigue, whereas dissimilar previous experiences (e.g., having had other types of surgery) failed to predict either expectancy. This suggests that only past experiences judged by an individual to be identical to the anticipated experience have a bearing on expectancies. Finally, in terms of extant pre-surgical symptoms, pre-surgical fatigue predicted increased expectancies for post-surgical fatigue but not pain, whereas pre-surgical pain predicted neither expectancy. This finding suggests that current experience of symptoms may play an important role in shaping expectancies for those specific symptoms in the future. However, this explanation raises the question of why current pain was not a significant predictor of expectancies for post-surgical pain. This null finding could be an artifact of the relative rarity of pre-surgical pain in breast cancer surgical patients. Therefore, future research with larger samples or higher background levels of pain should attempt to clarify this issue. Additionally, it is important to note that pre-surgical fatigue accounted for only 1.5% of the variance in expected post-surgical fatigue. This strongly indicates that although pre-surgical fatigue contributes to expectancies for fatigue, it is not their sole source. As Hofman et al. (2004, p. 856) suggest, expectancies are not just patients expecting “more of the same”.

A second issue is that a different set of factors was found to predict expectancies for post-surgical pain than expectancies for post-surgical fatigue. Apart from age, expectancies for post-sur-gical pain were predicted exclusively by emotional factors (distress, trait anxiety), whereas experiential factors (e.g., experienced fatigue, prior experience with the same surgical procedure) contributed to the prediction of fatigue above these emotional factors. The apparent specificity of the link between emotions and pain may relate to the fact that pain is a more feared and upsetting post-surgical outcome (Jenkins et al., 2001; Rashiq & Bray, 2003). However, as the present study is to our knowledge the first to report the apparent specificity of the link between distress and expectancies for pain, additional research is needed.

Although not hypothesized, age was found to correlate negatively with expectancies for post-surgical pain. This relationship is congruent with previous research which found older surgery patients to expect less intense post-surgical pain than younger patients (Gagliese, Jackson, Ritvo, Wowk, & Katz, 2000). In addition, our finding is consistent with a recent study of cancer patients about to begin treatment, in which patients over age 60 expected to experience fewer side effects during treatment than younger patients (Hofman et al., 2004). The positive correlation between education and expectancies for post-surgical fatigue is also consistent with the literature, which has found that patients with at least a high school degree expected greater fatigue than less educated patients (Hofman et al., 2004).

In reviewing these results, it is important to keep in mind certain limitations. First, although prospective, the relationships described in the present study are path analytic, and definitive conclusions about causality are best drawn from experimental research. Second, the present sample was entirely composed of women awaiting breast cancer surgery. Therefore, one must be cautious in generalizing the findings to men or to individuals dealing with other types of cancer or surgery. Third, the present study focused exclusively on expectancies for post-surgical pain and fatigue, and generalizability to other response expectancies is unknown. Fourth, the list of predictor variables included in this study should by no means be considered exhaustive, as they accounted for approximately 14% of the variance in expectancies for post-surgical pain and 18% of post-surgical fatigue. Although we assessed patients’ experience of previous surgeries and their family histories, we did not specifically assess the amount of pain or fatigue experienced following those surgeries and/or by their family members. Additionally, we did not assess expected post-surgical pain control, pain-related anxiety, pain catastrophizing, or fear of pain, all of which might contribute to the prediction of expected post-surgical pain. Future research might benefit from including such assessments. Finally, future research might benefit from testing a path model wherein variables found to be significantly related to expectancies in the current paper would be used to predict expectancies, and those expectancies in turn would be used to predict actual post-surgical pain and fatigue. Such a model would provide the most comprehensive understanding to date of response expectancies and their effects.

Clinically, our findings, combined with the published literature, suggest that breast cancer surgical patients at greatest risk for expecting and experiencing post-surgical pain are distressed on the morning of surgery, trait anxious, and younger. Additionally, our findings, suggest that breast cancer surgical patients at greatest risk for expecting and experiencing post-surgical fatigue are distressed on the morning of surgery, trait anxious, have undergone the same procedure in the past, are fatigued prior to surgery, and are more educated. Consequently, it might be beneficial for clinicians to screen for and work with such patients prior to surgery to reduce their expectancies, since prior studies (e.g., Montgomery & Bovbjerg, 2004) have demonstrated a link between expectancies and post-surgical side effects.

Acknowledgement

Work supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA1055222, CA81137, CA88189) and the American Cancer Society (PF-05-098-01-CPPB). We would also like to express our gratitude to all of the women who participated in the study.

References

- American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2006. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bendig AW. The development of a short form of the Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1956;20:384. doi: 10.1037/h0045580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict S, Williams RD, Baron PL. Recalled anxiety: from discovery to diagnosis of a benign breast mass. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1994;21:1723–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Sloan P, Cunningham L, Cordova MJ, Studts JL, et al. Postmastectomy/postlumpectomy pain in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:1285–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: anemia and fatigue. Seminars in Oncology. 1998;25:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CKY, Lovibond PF. Expectancy bias in trait anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:637–647. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll AM, Ameen JR, Mead D. Postoperative pain assessment tools in day surgery: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;46:124–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane KA, Degner LF. Information needs, uncertainty, and anxiety in women who had a breast biopsy with benign outcome. Cancer Nursing. 1998;21:117–126. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita VT, Jr., Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer, principles and practice of oncology. J.P. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo TA, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH, Jacobsen PB, Valdimarsdottir H. The application of a shortened version of the profile of mood states in a sample of breast cancer chemotherapy patients. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:315–325. [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo TA, Jacobsen PB, Bovbjerg DH, Chang H, Hudis C, Sklarin N. Sources of anticipatory emotional distress in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 1995;6:705–711. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliese L, Jackson M, Ritvo P, Wowk A, Katz J. Age is not an impediment to effective use of patient-controlled analgesia by surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:601–610. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller BM, Oppenheimer RG, Mickey RM, Worden JK. Patient perceptions of breast biopsy procedures for screen-detected lesions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.10.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman M, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Mustian KM, Moore DF. Cancer patients’ expectations of experiencing treatment-related side effects. Cancer. 2004;101:851–857. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins K, Grady D, Wong J, Correa R, Armanious S, Chung F. Post-operative recovery: day surgery patients’ preferences. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2001;86:272–274. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8.57 for Windows. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. Changing expectations: A key to effective psychotherapy. Brooks/Cole; Pacific Grove: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Cameron L. Representations, procedures, and affect in illness, self-regulation: a perceptual-cognitive model. In: Baum A, Revenson T, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associations; Mahwah: 2001. pp. 10–47. [Google Scholar]

- Loeser JD, Melzack R. Pain: an overview. Lancet. 1999;353:1607–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DE, Rose JB. Is postoperative pain a self-fulfilling prophecy? Expectancy effects on postoperative pain and patient-controlled analgesia use among adolescent surgical patients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30(2):187–196. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Expectations of chemotherapy-related nausea: emotional and experiential predictors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25:48–54. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Pre-surgery distress and specific response expectancies predict post-surgery outcomes in surgery patients confronting breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23(4):381–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, David D, Goldfarb AB, Silverstein JH, Weltz CR, Birk JS, et al. Sources of anticipatory distress among breast surgery patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:153–164. doi: 10.1023/a:1023034706298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Kirsch I. Classical conditioning and the placebo effect. Pain. 1997;72:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Weltz CR, Seltz G, Bovbjerg DH. Brief pre-surgery hypnosis reduces distress and pain in excisional breast biopsy patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2002;50:17–32. doi: 10.1080/00207140208410088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. The emergence of the ‘waiting game’: a critical examination of the psychosocial issues in diagnosing breast cancer. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25:273–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, Milling LS, Kirsch I, Duff A, Montgomery GH, Nicholls SS. An analysis of factors that contribute to the magnitude of placebo analgesia in an experimental paradigm. Pain. 1999;83:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashiq S, Bray P. Relative value to surgical patients and anesthesia providers of selected anesthesia related outcomes. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2003;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB. The development and application of social learning theory. Praeger; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Hall GM. A theory of postoperative fatigue: an interaction of biological, psychological, and social processes. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1997;56:623–628. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1983;47:305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Anxiety and behavior. Academic Press; New York: 1966. Theory and research on anxiety; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Current trends in theory and research. Academic Press; New York: 1972. Conceptual and methodological issues in anxiety research; pp. 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Snider PR. Coping with a breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective study. Health Psychology. 1993;12:16–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, Kirsch I. Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain. 2001;91:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA. A personality scale of manifest anxiety. Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1953;48:285–290. doi: 10.1037/h0056264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace LM. Surgical patients’ expectations of pain and discomfort: does accuracy of expectations minimise post-surgical pain and distress? Pain. 1985;22:363–373. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F. Fatigue assessments in rheumatoid arthritis: comparative performance of visual analog scales and longer fatigue questionnaires in 7760 patients. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:1896–1902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GK, Friedman LL. Physical and psychosocial outcomes of midlife and older women following surgery and adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1998;25:761–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]