Abstract

Despite its centrality to social stress theory, research on the social patterning of stress exposure and coping resources has been sparse and existing research shows conflicting results. We interviewed 396 gay, lesbian and bisexual, and 128 heterosexual people in New York City to examine variability in exposure to stress related to sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. Multiple linear regression showed clear support for the social stress hypothesis with regard to race/ethnic minority status, somewhat mixed support with regard to sexual orientation, and no support with regard to gender. We discuss this lack of parsimony in social stress explanations for health disparities.

Keywords: social stress, stigma, prejudice, discrimination, sexual minorities, health disparities, coping, gender, race, USA

Healthy People 2010 identified eliminating health disparities in the United States as a goal for the first decade of the 21st century. Health disparities, and the efforts to reduce them, focus on social groups that have a higher prevalence of morbidity or mortality than would be expected if diseases were randomly distributed. Socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation are among the characteristics used to define these social groups (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

Social stress theory provides a useful theoretical framework to explain health disparities (Dressler, Oths, & Gravlee, 2005). Aneshensel, Rutter, and Lachenbruch (1991) described this framework as a sociological paradigm that views social conditions as a cause of stress for members of disadvantaged social groups. This stress, in turn, can cause disease. The authors noted that, as Pearlin (1989) had observed, “the various structural arrangements in which individuals are embedded determine the stressors they encounter” (p. 167) as well as their coping resources.

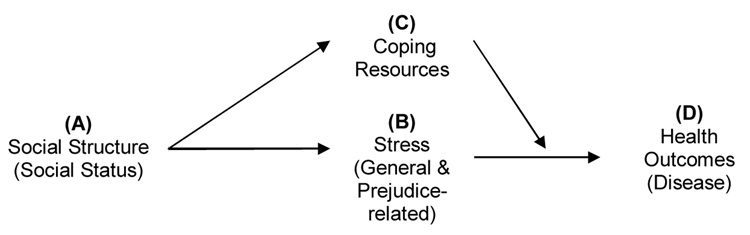

Figure 1 depicts this sociological model: social structure (A)—and the specific component of interest here, social status—influences exposure to stress (B). We distinguish two components of stress—general stress and stress that is attributable to prejudice. Stress, in turn, is a potential cause of disease (D). In addition, the figure shows that coping resources (C), such as personal resources and social support, are also socially distributed. These resources can moderate the impact of stress on disease, acting as stress buffers (Wheaton, 1985). (This schema omits elaborations of the stress and coping process [see Dohrenwend, 1998] because, despite their significance in understanding stress and illness, they are immaterial to the aims of this paper).

Figure 1.

The sociological paradigm: A causal model of social structure and health

In statistical language, social stress theory describes a mediator in the relationship of social structure and illness (Figure 1): it explains “how structured risks become actualized in the lives of individuals as stressful experiences” (Thoits, 1999, p. 137). Noting the difference between viewing stressful events as random conditions and viewing them as patterned by social structure, Aneshensel and Phelan (1999) explained: “The question is not whether there will be unemployment-related disorder, but rather who is at greatest risk for unemployment and, hence, disorder.” That is, the stress model aims to show that “high levels of disorder among certain groups can be attributed to their extreme exposure to social stressors or limited access to ameliorative psychosocial resources” (p. 12).

To test this sociological model, researchers need to examine whether stress and coping act as mediators in the causal relationship between social structure and disease (Aneshensel et al., 1991). This implies at least two testable hypotheses: that social structure patterns stress exposures and coping resources and that this stress, in turn, causes disease with coping serving as a buffer.

Surprisingly, despite its centrality to social stress theory, explicit tests of the first element—the social patterning of stress exposure—have been sparse (Hatch & Dohrenwend, in press; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Turner & Avison, 2003; Turner & Lloyd, 1999; Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995). Studies of health disparities have, instead, generally focused on the outcome—showing that disease prevalence varies by social status or stress exposure—providing support for the hypothesis that social status or stress is related to the patterning of disease (A and D or B and D in Figure 1). But to fully test the causal hypotheses implied by the sociological paradigm, researchers also need to establish that stress exposure is socially patterned (A and B). As Turner and colleagues (1995, p. 106) noted, this test would examine “a fundamental hypothesis in sociology that differences in stress experience arise, at least partially, from patterned differences in life circumstances that directly reflect the effects of social inequality on allocations of resources, status, and power.”

This paper examines this element of the stress paradigm and thus adds a crucial test of social stress theory to the existing stress literature. This paper also adds a unique aspect in that it explores the question of stress exposure among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals—a group that has not been sufficiently studied in this context.

Disadvantaged Social Groups

There is a long history of inquiry into the impact of social class on health and well being. This work has produced strong and consistent evidence (Evans, Barer, & Marmor, 1994; Kawachi, Kennedy, & Wilkinson, 1999; Wilkinson, 1996). In this paper we focus on forms of group disadvantage that stem primarily from prejudice, discrimination, and stigma. United States law noted (a) “that the opportunity for full participation in our free enterprise system by socially and economically disadvantaged persons is essential if we are to obtain social and economic equality for such persons and improve the functioning of our national economy”; and (b) “that many such persons are socially disadvantaged because of their identification as members of certain groups that have suffered the effects of discriminatory practices or similar invidious circumstances over which they have no control” [15 U.S.C. § 631(f)]. The European Union and the World Health Organization use the term social exclusion to denote a similar concept. Using this term to expand beyond poverty and socioeconomic concerns, social exclusion refers to many resources that people may be excluded from, including “a livelihood; secure, permanent employment; earnings; property credit, or land; housing; minimal or prevailing consumption levels; education, skills, and cultural capital; the welfare state; citizenship and legal equality; democratic participation; public goods; the nation or the dominant race; family and sociability; humanity, respect, fulfillment and understanding” (Silver, 1995, in Popay, Enoch, Johnston, & Rispel, 2006, p. 5).

Our interest is grounded in classical social theory on the impact of social stratification on the lives of individuals, with roots in the works of Merton, Durkheim and others (Aneshensel & Phelan, 1999). The most basic idea is that social position confers benefits and disadvantages that may impact well being and health (Thoits, 1999). Here we test social stress hypotheses among social groups defined by sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender—significant social categories in American society (Collins, 1998; Hanckck, 2007). That sexual minorities (lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals), race/ethnic minorities, and women have been disadvantaged, albeit different ways, is documented in legislation (e.g., related to discrimination and hate crimes [Nolan, Akiyama, & Berhanu, 2002]); public health planning and research, (e.g., as described in Healthy People 2010); and in psychosocial theory (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Kessler et al., 1999; Krieger, 2003; Meyer, 2003b).

That race/ethnicity and gender have been important social categories in sociological investigation needs little justification. Vega and Rumbaut (1991) noted in the Annual Review of Sociology that the study of racial/ethnic minorities and health addresses “core theoretical and empirical” issues in sociology (p. 352). In discussions of race/ethnicity, investigators from the stress tradition have focused on prejudice and discrimination to which members of racial/ethnic minorities are exposed (Allison, 1998; Clark et al., 1999).

Gender has been one of the most enduring categories of stratification in sociological analysis (Massey, 2007). The most dominant theoretical orientation regarding gender and stress explains women’s disadvantage in terms of role theory—e.g, dual role occupancy (work and family) or role overload (Barnett & Baruch, 1987; Gove & Tudor, 1973)—rather than prejudice and discrimination per se. But some writers reject the notions of role strain, claiming that gender, like race, should be discussed in terms of prejudice and discrimination (Lopata & Thorne, 1978). Others see role stress as significant but only (or mainly) because it explains why women experience more stressful events and strains than men: “it is not role occupancy per se that is critical to the stress process. It is, rather, that role occupancy increases the chances of exposure to some stressors and precludes the presence of others” (Aneshensel & Pearlin, 1987, p. 78).

Sexual orientation does not have as rich a history in sociological investigation. Sexuality had been largely ignored until the 1960s and 1970s (Epstein, 1994; Seidman, 1996). Nonetheless, as Epstein (1994, p. 189) observed, the relevance of sexuality to sociological inquiry is apparent. “Even a moment’s reflection,” he said, “suggested that the domain of sexuality—a domain of elaborate and nuanced behavior, potent and highly charged belief systems, and thickly woven connections with other arenas of social life—was deeply embedded in systems of meaning and was shaped by social institutions.” Despite debates within sociology—mostly from the queer theory perspective—about the validity and utility of gay and lesbian as discrete categories in sociology, researchers agree that gay and lesbian populations are an important focus of sociological study (Green, 2002). As policy and civil rights issues regarding lesbians and gay individuals emerge—marriage and service in the military, for example—and are shaping major political and social battles, and as disparities between LGBs and heterosexuals in health outcomes have become a focus of concern, sexual orientation has come to define an important social category in American and other western societies.

The approach we take for social categorization represents a cornerstone of sociological thinking. But in recent years it has come under review with the introduction of, on one hand, postmodernist thinking that questions the legitimacy of all categories (Brubaker, 2004; Lamont & Molnar, 2002), and on the other hand, intersectionality, which criticizes unitary categories, such as those based on sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, or gender, because they obscure important within-group distinctions (Glenn, 2000; Jackson, 2005). Researchers from this perspective point out that more nuanced understanding can be gained if we think about group intersections. The argument is that a single category (e.g., gender) obscures important differences that intersectionality highlights, for example between black and white women. We return to this issue when we discuss our results regarding gender.

Despite such critiques, the social strata we use are still among the most common and influential categories in social and political science, in health research, as well as in popular discourse (Massey, 2007). As a result, many of our theories, in particular stress theory, have proposed testable hypotheses about these groups (Aneshensel & Phelan, 1999; Meyer, 2003b; Thoits, 1999; Vega & Rumbaut, 1991). The sociological hypotheses about the impact of disadvantaged social statuses we test ask whether a disadvantaged status on average—regardless of variability among group members—imposes a greater burden on group members than on the relevant comparison group. Specifically, we investigate whether as a group sexual minorities, racial/ethnic minorities, and women, by virtue of their disadvantaged location in the stratification system, experience more stressors than heterosexuals, whites, and men, respectively. Our tests of stress hypotheses may also have implications for the very question of group categorization. To the extent that the social categories we use evidence the hypothesized effects, they demonstrate their explanatory power and, therefore, their continued utility.

The Stress Construct

Stress theory is a useful, and often-used, sociological model to explain the relationship between social disadvantage and health (Scheid & Horwitz, 1999; Aneshensel & Phelan, 1999). We distinguish between two types of stress conferred by social disadvantage, experiential stress and structural stress. Experiential stress includes events and conditions that tax the individual’s capacity to cope (e.g., being fired from a job). These events are typically experienced as stressful by most people, although they do not have to be appraised as stressful by all individuals experiencing them. For example, Dohrenwend (2006) advocates for an objective definition of stressors. According to him, it is the event’s capacity to induce change, and its typical, or average, stressfulness that defines it as a stressor. This definition, and corresponding measurement methods, disregard, and, indeed, aim to circumvent, the individual’s own assessment of these events or conditions. This is distinct from Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) more subjective approach to stress, which defines as stressors only those events and conditions that are appraised by individuals as stressful (Meyer, 2003a).

A relatively recent application of this social stress model has been to the study of stress related to prejudice (Allison, 1998). Prejudice can be stressful in many ways, most notably in that it can lead to discrimination and unfair treatment. For example, Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams (1999) noted that “perceived discrimination is one of the most important secondary stresses associated with major stressor events such as job loss and exposure to violence” (p. 209–10). Other manifestations of prejudice are hate crimes ranging from harassment to violence (Allport, 1954).

In addition to experiential stress—whether defined objectively or subjectively—there are structural or institutional conditions that impact disadvantaged populations even in the absence of specific identifiable events (Adams, 1990; Link & Phelan, 2001; Meyer, 2003b; Wheaton, 1999). For example, Adams (1990) described racism as a structural stressor—a general condition of black individuals in American society—independent of life events that are associated with these conditions. He noted that that as a structural stressor, racism thwarts prosperity, esteem and honor, and power and influence. For example, inferior school systems (or other noxious environmental conditions) that result from racism impact the lives of many black individuals. But such conditions are not necessarily associated with stressful events and are not typically experienced as stressors.

Stress and Coping by Sexual Orientation, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender

Few studies have explicitly examined the distribution of exposure to stress related to sexual orientation. Mays and Cochran (2001) found LGB individuals reported greater exposure to both lifetime and day-to-day experiences with discrimination than heterosexuals. And few studies examined variation in stress exposure among LGB subgroups. They found a gender pattern similar to that found in heterosexual populations: gay men had more stress related to HIV/AIDS and violence than women, but women had more stress related to family reactions to their partners (Lewis, Derlega, Berndt, Morris, & Rose, 2001; Mays & Cochran, 2001). In another study, Lewis, Derlega, Grifiin, and Krowninski (2003) found no differences between gay men and women in exposure to either general or gay-related stressors. In terms of race/ethnicity, Krieger and Sidney (1997) found that black lesbians reported more gay-related discrimination than black or white gay men.

Regarding race, although there are some exceptions (Norris, 1992), most researchers have found that blacks, and often other ethnic/racial minorities, are exposed to greater stress (Turner & Lloyd, 2004) and, specifically, greater exposure to discrimination than non-Hispanic whites (Kessler et al., 1999). Indeed, researchers have noted that the “patterns of findings … are uniform and striking in their clarity” (Turner & Avison, 2003, p. 495).

Evidence with regard to stress and gender has been mixed for decades (Thoits, 1983; Hatch & Dohrenwend, in press). Although Turner and Lloyd (1999) found that women were exposed to more stress than men, today, most researchers agree that women, as a group, are not exposed to more stress than men. Rather, they conclude that women and men are exposed to different types of stressors. For example, women are exposed to more stressors associated with the cost of caring, such as having greater responsibilities for social network members or experiencing more deaths of friends (Turner & Lloyd, 2004; Turner et al, 1995). Consistently, Kessler and colleagues (1999) found that men and women did not differ in exposure to acute discrimination events. Although women were more likely than men to have been denied/received inferior services (e.g., from a mechanic), men were more likely to have been discouraged by a teacher from seeking higher education, denied a bank loan, and hassled by police. On their measure of chronic, more minor (“everyday”) discrimination, men were more likely than women to have experienced discrimination often.

Mastery and Social Support

Coping resources, such as mastery and mobilization of social support, are an integral part of the stress process. They have both stress-buffering and direct salutogenic effects on health (Dohrenwend, 1998; Wheaton, 1985). Coping resources, like stress exposure, are individual variables that can be socially patterned. For example, mastery and sense of control appear to be lower among people in lower socioeconomic strata, which may be “reflective of the actual variations in life situations among social class groups” (Lachman & Weaver, 1998, p. 771). Evidence regarding race is scarce: although some studies found that among older adults, African Americans had a lower sense of mastery than whites (Jang, Borenstein-Graves, Haley, Small, & Mortimer, 2003), other studies did not confirm this association (Heckman, Kochman, Sikkema, Kalichman, Masten, & Goodkin, 2000). Studies of self-esteem, which is associated with mastery, have found that blacks have a higher self-esteem than whites, although the results for Latinos is mixed (Twenge & Crocker, 2002). The evidence regarding gender is also mixed but it is generally believed that, as with socioeconomic status, the lower status and power that women are allotted would lead to lesser sense of personal mastery but that women have more and better social support than men (Turner & Lloyd, 1999).

In the context of stress related to prejudice and discrimination coping resources can also be conceived as a group-level resource that is accessible to members of stigmatized groups by identification and participation in their community (Crocker & Major, 1989). For example, by identifying as lesbian or gay and participating in the gay community, gay people can benefit from gay affirmative values and norms (Meyer & Dean, 1998).

Rationale for the Current Study

We test a fundamental premise of social stress theory—that disadvantaged social status confers excess stress and fewer coping resources. We thus hypothesize that, in addition to and independently of social class, disadvantaged social statuses related to sexual orientation (LGB individuals), race/ethnicity (blacks and Latinos), and gender (women) would be associated with greater exposure to stressors and fewer coping resources. Further, following writers who have described added burden associated with multiple minority identities (Diaz, Ayala, Edward, Jenne, & Marin, 2001; Mays & Cochran, 1994) we augment the stress hypothesis, above, with the hypothesis that each disadvantaged social status will be related to an increment in exposure to stress related to the unique prejudice and stigma attached to it.

METHODS

Sampling and Recruitment

We used a venue-based sampling of both LGB and straight respondents. Sampling venues were selected to ensure a wide diversity of cultural, political, ethnic, and sexual representation within the demographics of interest and included business establishments, such as bookstores and cafes, social groups, outdoor areas, such as parks, as well as snowball referrals (respondents were asked to nominate up to 4 potential participants). To reduce bias, venues were excluded from our venue-sampling frame if they were likely to over- or under-represent people receiving support for mental health problems (e.g., 12-step programs, HIV/AIDS treatment facilities) or people with a history of significant life events (e.g., organizations that provide services to people who have experienced domestic violence). Outreach workers received training regarding the geographic and ethnographic aspects of the types of venues targeted for recruitment before beginning work in the field.

Between February 2004 and January 2005, 25 outreach workers visited a total of 274 venues in 32 different New York City zip codes. In each venue, outreach workers who approached potential study participants and invited them to participate in the study. They described the study as concerning the health of “New York City communities,” in venues that were primarily nongay (e.g., a Barnes and Noble bookstore) or the health of “lesbian, gay, and bisexual communities,” in venues that catered primarily to LGB individuals (e.g., Brooklyn gay pride event). At the venues, outreach workers completed a brief screening form for each potential participant to determine his/her eligibility. Respondents were eligible if they were 18–59 years-old, resided in New York City for two years or more and self-identified as: (a) heterosexual or lesbian, gay, or bisexual; (b) male or female (and their identity matched sex at birth); and (c) white, black or Latino; but they could have used other labels referring to these identities. Because the study design called for a comparison of LGB groups with white heterosexuals, no black or Latino heterosexual respondents were included.

To select respondents from among eligible individuals we used quota sampling to ensure approximately equivalent numbers of respondents of similar age, across sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender groups. Selected eligible respondents were contacted by trained research interviewers and invited to participate in the study. Interviews were conducted in person at the research office; they lasted 3.8 hours on average (SD = 55 minutes).

The cooperation rate for the study was 79% and the response rate was 60% (AAPOR, formula COOP2 and RR2, respectively). Response and cooperation rates did not vary greatly by sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, or gender. Recruitment efforts were successful at reaching individuals who resided in diverse New York City neighborhoods and avoiding concentration in particular “gay neighborhoods” that is often characteristic of sampling of LGB populations. Respondents resided in 128 different New York City zip codes and no more than 3.8% of the sample resided in any one zip code area. (Detailed information about the study’s methodology is available online at http://www.columbia.edu/~im15/)

Respondents

A total of 524 eligible individuals were interviewed. The 396 LGB respondents included equal numbers of white (34%, n = 134), black (33%, n = 131), and Latino (33%, n = 131) respondents and equal numbers of men (50%, n = 198) and women. The heterosexual comparison group consisted of 128 white men (51%, n = 65) and women (49%, n = 63). The sample’s mean age was 32 (SD = 9); 19% had education equal to or less than a high school diploma (n = 97); 52% (n = 267) had a negative net worth (they owed more than their total assets); and 16% (n = 83) were unemployed. The Latina lesbian/bisexual women were the least educated (30%, n = 20 having a high school diploma or less); the black lesbian/bisexual women had the highest proportion of negative net worth (73%, n = 45); and the straight white men had the highest rate of unemployment (25%, n = 18).

Measures

Predictor Variables

Social Statuses

Social statuses were assigned based on self-report of sexual orientation (straight, gay/lesbian, or bisexual), race/ethnicity (white, black, or Latino), and gender (male or female). Respondents may have used other identity terms (“African American,” “queer”) in referring to these identities.

Outcome Variables

Chronic Stress

Stigma

(6 items, alpha = .88). This measure was based on a scale developed by Link (1987) to assess stigma of mental illness. We adopted the scale so that the stigmatized condition was not mental illness and so that it could be applied to multiple social categories at once. Interviewers first read the following instructions: “These next statements refer to ‘a person like you’; by this I mean persons who have the same gender, race, sexual orientation, nationality, ethnicity, and/or socioeconomic class as you…. I would like you to respond on the basis of how you feel people regard you in terms of such groups.” Respondents answered questions such as: “Most people would willingly accept someone like me as a close friend” on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 “agree strongly” to 4 “disagree strongly.”

Experiences of everyday discrimination

(8 items, alpha = .84). This measure was modified from Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson (1997) so that it could be applied to a racially diverse sample. It assessed the frequency of the following 8 types of day-to-day experiences: being treated with less courtesy, less respect, receiving poorer services, being treated as not smart, people acting like they are afraid of you, people acting like you are dishonest, people acting like they are better than you, and being called names or insulted. One item from the original measure “being threatened or harassed” was not included in the current study as these experiences were assessed as part of the stressful life event measure. Lifetime frequency of occurrence was coded on a 4-point scale (1= “often” through 4= “never”). For each item that they endorsed, after endorsing it, respondents were asked whether the experience was related to their sexual orientation, gender, ethnicity, race, age, religion, physical appearance, income level/social class, or some other form of discrimination.

Chronic strains

(28 items, alpha = .73 for the total scale, alphas for subscales with more than 2 items are reported below). This scale is based on Wheaton’s (1999) conceptualization of chronic strain. In compiling items for the scale we followed the procedure used by Turner and others (e.g., Turner & Avison, 2003; Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995) aiming to make the items culturally relevant to our respondents. Although most items were from scales developed Turner and colleagues, additional items were developed or adjusted to apply to the diverse target population (e.g., Lewis et al., 2001). Items inquired about sources of chronic strain in 13 areas of life: Job/Work (5 items, alpha = .80); Unemployment (1 item); Finances (1 item); Education (1 item); Parenting (1 item); Residence (2 items); Relationships (7 items, alpha = .84); Loneliness (3 items, alpha = .59); Significant Other’s Illness/Health (1 item); Caretaking Responsibilities (1 item); Relationship with Parents (1 item); Wanting Children (1 item); and General Strain (3 items, alpha = .57). Respondents were asked to indicate whether statements such as “You’re trying to take on too many things at once” (General Strains) or “You are alone too much” (Loneliness) were presently “not true,” “somewhat true,” or “very true.”

Acute Stress

Life events

The life events measure was designed to arrive at a more objective description than is provided by the measures above that completely rely on the respondent’s subjective assessment of the event and his/her attribution regarding prejudice and discrimination. This limits confounding of reports of prejudice with correlates of perception (e.g., strength of group identity or the impact the event has had) (Meyer, 2003a).

Stressful life events were measured by first asking a respondent whether or not he/she experienced at any time in his/her life any of 47 classes of events (e.g., loss of a job, death of a loved one, childhood abuse) and then carefully probing each experienced event to produce a brief event narrative. Each event narrative was later read and rated by 2 independent raters following Dohrenwend and colleagues’ (1993) strategy to assess the event’s dimensions, including the magnitude of change the event typically produces in everyday activities of people who experience it [ratings ranged from 0 (“no change”) to 4 (“a major amount of change”)]; and whether the event involved prejudice (“yes” or “no”). If an event was assessed to involve prejudice, the raters also coded the type of prejudice that was involved (age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, SES, physical appearance, religion, or other). To assess reliability, we evaluated the consistency between the raters. Of all possible event ratings (N = 77,085), only 2% were discrepant (defined as greater than 1 unit on the scale of 0 to 4 or any disagreement on the 0/1 scale), indicating a high degree of reliability. In cases where disagreement had occurred, ratings were reconciled at a consensus meetings attended by at least 3 raters. Two measures of stress were derived from data collected using this measure: Large magnitude events: (counting only events with a magnitude rating of 3 or higher) and Prejudice events (counting all prejudice-involved events).

Coping

Mastery

(7 items, alpha = .64). We used the mastery scale developed by Pearlin and Schooler (1978) to tap perceptions of control through items such as: “You have little control over the things that happen to you” and “You often feel helpless in dealing with problems in life.” Respondents rated their agreement with these statements on a 3-point scale (“not true,” “somewhat true,” and “very true”).

Social support networks

We used a measure developed by Fisher (1977) and adapted by Martin and Dean (1987) for use in gay/bisexual men. Respondents were first asked if they received support in the year prior to interview in 10 areas, including, help with household projects or tasks, social companionship, and borrowing money. For each area of support, a respondent identified individuals who provided support and their basic demographic information. The current analyses use measures of network size defined as the total number of individuals mentioned in the respondent’s social support network.

Prominence of LGB identity

Respondents rated each identity that they had nominated on a set of 70 attributes (e.g., talented, guilty, unhappy). HICLAS method was used to analyze the identities and identity attribute ratings (Deboeck & Rosenberg, 1988). The prominence of the identity was coded on a range from 0 (low) to 4 (high). (See Stirratt, Meyer, Ouellette, & Gara, in press, for details on this approach to measurement of identity).

Connectedness to the LGBT community

(8 items, alpha = .80). Using questions from Mills and colleagues (2001) to apply to the communities of interest, respondents are asked to assess on a 4-point scale (1 = “agree strongly” through 4 = “disagree strongly”) how “connected” they felt to the gay community (e.g., “I really feel that any problems faced by NYC’s LGBT community are also my problems).

LGB group participation

This instrument was developed by Mills et al. (2001) and tapped 9 organizational memberships and activities such as professional or business meetings, a gym, and religious congregation. For each organization or activity endorsed, respondents indicated (“yes” or “no”) whether it was heavily attended by other LGB people. The scale’s score was the total number of groups a respondent participated in that were heavily attended by other LGBs.

Control Variables

Education

Education was a coded as a dichotomous variable indicating whether respondents had obtained less than or equal to a high school diploma (= 1) or higher education (= 0).

Negative net worth

Respondents calculated how much they would owe, or have left over after converting all assets to money and paying all debts (Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd, & Brody, 2002). Responses were coded into a dichotomous net worth variable, with “1” indicating negative net worth.

Unemployment

Respondents were asked to state their current employment status.

Analytic Approach

To test our hypotheses we examined different sets of contrasts that feature our selected social statuses. We first tested the hypothesis that minority sexual orientation, and the stigma, prejudice, and discrimination directed at sexual minorities, confers unique stress exposure. We hypothesized that white gay and bisexual men would be exposed to more stress than white heterosexual men. Testing the hypothesis about gender, we predicted that white heterosexual women would be exposed to more stress than white heterosexual men. Consistent with the incremental stress (added burden) hypothesis, we further expected that lesbians and bisexual women would be exposed to greater stress than heterosexual women due to their added disadvantaged sexual minority status, and that lesbian and bisexual women would be exposed to greater stress than gay and bisexual men due to their added disadvantaged gender status. Finally, we hypothesized that black and Latino LGBs would be exposed to greater stress than white LGBs because of the added minority racial/ethnic status.

Despite important cultural differences between blacks and Latinos, and, indeed, among subgroups within those groups, we combined them into a single racial/ethnic minority category consistent with social stress theory. The differences between blacks and Latinos are not pertinent for testing our sociological model, which is concerned with disadvantage in general (Schwartz & Meyer, 2006). Despite this conceptual rationale, we tested whether our combined category hides statistically significant differences and found no differences in patterns of stress exposure between blacks and Latinos.

We used multiple linear regressions to test the impact of social status on exposure to stress and coping resources. We began each regression model by contrasting the reference category—defined as white heterosexual males—with the disadvantaged categories simultaneously: sexual minority status (LGB = 1), race/ethnic minority (black or Latino = 1), and gender (female = 1). It is important to recall that the sample does not include black and Latino heterosexuals, so the category of racial/ethnic minority refers to LGBs who are of racial/ethnic minority compared with white LGBs. We controlled for socioeconomic status and unemployment in all models.

These analyses were repeated after excluding the heterosexual men and women to test whether racial/ethnic minority LGBs had significantly more stress exposure than white LGBs. Additional models tested the interaction between gender and sexual orientation in explaining the outcomes. In a series of additional analyses, we tested the extent to which race/ethnic minority LGBs differed from white LGBs in the nature of discrimination that they experienced by conducting t-tests comparing the two groups on exposure to everyday discrimination and stressful events involving prejudice related to sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender separately.

Missing data were minimal on all the measures. The maximum number of participants with missing data was for the measure of net worth (15) followed by chronic strain (8), connectedness to the LGB community (6), stigma (5), and mastery (1). To address missing data we first tested subgroup differences in missing items and found no systematic error based on groups defined by sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, gender, and age. We then used mean substitution by replacing missing values with the mean for the measure of other participants with the same race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. That is, if a gay black man was missing a value on mastery, we substituted the missing value with the mean for other gay black men. For net worth, we substituted the mode.

RESULTS

Exposure to Stressors

Being a woman was not associated with an excess of perceived everyday discrimination, chronic strains, number of general or prejudice-related stressful events (Table 1). Indeed, women were exposed to fewer prejudice events than men. In the models shown in this table, women seem to have somewhat higher levels of expectations of stigma. We tested the interaction of gender and sexual orientation. (Because the addition of this interaction term did not alter the interpretation of results for any of the other outcomes, these models are not shown). In the model that included the interaction along with the predictor and control variables shown in Table 1 the regression coefficient for the interaction term was appreciable (B = .27, SE = .14, p = .06). In the model without the interaction term, the regression coefficients for gender and LGB orientation were B = .10 (SE = .06, p = .09) and B = 0.26 (SE = 0.08, p < 0.01), respectively. In the model with the interaction term these coefficients were B = −.10 (SE = .12, p = .42) and B = 0.13 (SE = 0.11, p = 0.25). There was little change in the magnitude of the coefficients for the intercept and control variables. This interaction suggests that the gender effect for stigma was mostly attributed to lesbians and bisexual women.

Table 1.

Gender, race/ethnic minority, and sexual minority statuses as predictors of exposure to general and prejudice-related stress (N = 524)

| Prejudice-Related Stress | General Stress | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes → | Expectations of Stigma | Perceived Everyday Discrimination | Number of Prejudice-Related Stressful Events | Chronic Strains | Number of Large-Magnitude Stressful Events | ||||||||||

| Predictors | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| (Intercept) | 1.3 | .07 | .00 | 2.25 | .06 | .00 | .24 | .09 | .01 | 1.29 | .02 | .00 | 1.17 | .24 | .00 |

| Networth | .18 | .06 | .00 | .15 | .05 | .00 | −.01 | .08 | .95 | .06 | .02 | .00 | −.08 | .2 | .67 |

| Unemployment | .18 | .08 | .03 | .01 | .07 | .87 | .04 | .11 | .69 | .00 | .03 | .97 | 1.54 | .28 | .00 |

| ≤ HS Education | .06 | .08 | .44 | −.06 | .07 | .4 | −.1 | .1 | .32 | .05 | .03 | .05 | .39 | .27 | .14 |

| Female | .1 | .06 | .09 | −.06 | .05 | .24 | −.23 | .08 | .00 | .03 | .02 | .11 | .23 | .2 | .24 |

| Minority | .47 | .07 | .00 | .17 | .06 | .01 | .22 | .09 | .02 | .1 | .02 | .00 | .98 | .25 | .00 |

| LGB | .26 | .08 | .00 | .01 | .07 | .86 | .46 | .11 | .00 | .02 | .03 | .48 | .59 | .28 | .03 |

| F | 25.16 | 4.2 | 10.39 | 11.55 | 16.09 | ||||||||||

| R2 | .23 | .05 | .11 | .12 | .16 | ||||||||||

Note: The table presents Bs, standard errors, and significance levels from multiple regression analyses with all the independent variables included simultaneously.

LGB status was related to greater exposure to large magnitude life events and to prejudice-related life events but not to perceived everyday discrimination or chronic strains. The results (Table 1) suggest that LGB status was associated with increased expectations of stigma, but, as noted above, the inclusion of an interaction term suggests that the effect was largely attributable to lesbians and bisexual women and the effect for gay and bisexual men was not appreciable.

The data in Table 1 also show that racial/ethnic minority LGB individuals had consistently higher levels of exposures to both general and prejudice-related stressors than white heterosexual men. In all analyses, racial/ethnic minority status added substantial stress exposure to the stress associated with sexual minority status. In subsequent analyses (not shown) in the LGB sample only (with the white LGB respondents as the referent group) we examined whether racial/ethnic minority status was related to a statistically significant increment in stress exposure (we used the variables shown in Table 1 except for LGB status, which was invariant in these analyses). In each of the 5 analyses corresponding to the outcomes listed in Table 1, the black/Latino LGBs had appreciably and significantly more stress than the white LGBs.

We also examined the source of the increase in stress exposure among black and Latino LGBs as compared with the white LGBs. We tested whether the excess stress exposure in black and Latino LGBs was related to prejudice directed at sexual orientation or racial/ethnic identity. To determine the source of prejudice, we used independent raters’ assessment (for prejudice events) or self attributions (for everyday discrimination). We found no differences between racial/ethnic minority and white LGBs in exposure to antigay prejudice, but, racial/ethnic minority LGBs were exposed to significantly more racial/ethnic prejudice than white LGBs (both life events and everyday discrimination, t = −14.25, df = 394, p < .001; t = −3.92, df = 388, p < .001; respectively).

As noted above, racial/ethnic minority status, but not being female and sexual minority status, was related to a higher level of chronic strain. However, there was significant variation in the types of strains to which members of these groups were exposed (see Table 2). For example, while women and LGBs did not have higher scores of total chronic strain than men and heterosexuals, respectively, they did have more strains in some specific domains: compared with men, women had somewhat elevated levels of chronic strains related to parenting, relationships, caretaking, and residence. Compared with white heterosexuals, LGBs had somewhat elevated chronic strains related to wanting kids, education, caretaking, and relationships with parents. Compared with whites, LGBs of ethnic/racial minority had elevated strains related to finances, parenting, relationships, residence, and general strains (i.e., ambient strains like trying to take on too many things at once).

Table 2.

Gender, race/ethnic minority, and sexual minority statuses as predictors of chronic strains (N = 524)

| Independent Predictors → | Women | Black or Latino LGB | LGB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (vs. men) | (vs. White LGB) | (vs. heterosexual) | |||||||

| Outcomes | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Job Related | −.04 | .04 | .41 | .09 | .05 | .11 | .03 | .06 | .68 |

| Finances | 0 | .06 | .98 | .23 | .08 | .00 | −.03 | .09 | .74 |

| Education | .1 | .06 | .11 | −.02 | .08 | .83 | .17 | .09 | .07 |

| General | .05 | .05 | .33 | .17 | .06 | .00 | 0 | .07 | .98 |

| Parenting | .11 | .04 | .01 | .23 | .05 | .00 | −.04 | .06 | .47 |

| Residence | .13 | .05 | .01 | .18 | .06 | .00 | −.02 | .07 | .79 |

| Unemployment | −.02 | .03 | .48 | 0 | .04 | .96 | .02 | .04 | .6 |

| Relationships | .08 | .03 | .00 | .07 | .03 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | .81 |

| Loneliness | −.07 | .05 | .13 | .09 | .06 | .11 | .01 | .07 | .89 |

| Sig. Other’s Health | .05 | .05 | .35 | −.04 | .07 | .58 | .05 | .08 | .54 |

| Caretaking | .07 | .04 | .09 | .04 | .05 | .47 | .1 | .06 | .06 |

| Rel. w/ parents | .1 | .06 | .11 | −.02 | .08 | .83 | .17 | .09 | .07 |

| Wanting Kids | −.08 | .05 | .09 | .02 | .06 | .7 | .18 | .07 | .01 |

Note: The table presents Bs, standard errors, and significance levels from multiple regression analyses regressing each chronic strain outcome (column a) on independent predictors of being female (column b), a racial/ethnic minority (column c), and lesbian, gay or bisexual (column d). Regression coefficients are controlled for net worth, education, and unemployment as well as the three social status predictors (gender, race/ethnic minority, sexual minority).

Coping Resources

Table 3 shows social status differences in exposure to coping resources: racial/ethnic minority status was related to disadvantages in general forms of coping measured as a smaller social network and a lesser sense of mastery. But women and white LGBs did not have fewer coping resources than men and heterosexuals, respectively; indeed, women had significantly larger social support networks than their male counterparts.

Table 3.

Gender, race/ethnic minority, and sexual minority statuses as predictors of coping (N = 524)

| General | LGB Specific* | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes → | Mastery | Size of Social Support Network | Prominence of Sexual Orientation Identity | Connectedness to the LGBT community | # of LGB Group Participations | ||||||||||

| Predictors | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | B | B | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| (Intercept) | 2.71 | .03 | .00 | 6.9 | .32 | .00 | 3.56 | .08 | .00 | 3.24 | .06 | .00 | 2.17 | .17 | .00 |

| Networth | −.07 | .03 | .01 | −.09 | .27 | .75 | .09 | .07 | .22 | −.03 | .06 | .56 | −.06 | .16 | .7 |

| Unemployment. | −.12 | .04 | .00 | −.1 | .38 | .8 | −.06 | .1 | .53 | .08 | .08 | .32 | −.01 | .22 | .96 |

| ≤ HS Education | −.06 | .04 | .08 | −.79 | .36 | .03 | .11 | .09 | .23 | .01 | .07 | .84 | −.69 | .19 | .00 |

| Female | .03 | .03 | .26 | .58 | .27 | .03 | .21 | .07 | .00 | .06 | .05 | .27 | −.44 | .15 | .00 |

| Minority | −.06 | .03 | .06 | −1.65 | .33 | .00 | −.03 | .08 | .71 | .03 | .06 | .63 | −.2 | .17 | .23 |

| LGB | .02 | .04 | .56 | .14 | .38 | .71 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| F | 6.16 | 9.15 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 2.33 | ||||||||||

| R2 | .07 | .1 | .03 | .03 | .03 | ||||||||||

Note: The table presents Bs, standard errors, and significance levels from multiple regression analyses with all the independent variables included simultaneously.

Analyses reflect only the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) subsample (n = 396).

We also tested whether black and Latino LGBs differed from white LGBs in utilization of gay-related coping resources. Table 3 shows that racial/ethnic minority LGBs did not differ from white LGBs in the prominence of their sexual orientation identity, their sense of connectedness to the LGB community, or the number of LGB groups to which they belonged. Lesbians’ and bisexual women’s sexual orientation identities tended to be more prominent than gay and bisexual men’s. However, lesbians and bisexual women participated in significantly fewer LGB groups or organizations than the gay and bisexual men.

DISCUSSION

We tested the general hypothesis, derived from social stress theory, that disadvantaged social statuses related to sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender increase exposure to stress and reduce availability of coping resources. Furthermore, following the added-burden hypothesis, we predicted that membership in each disadvantaged social group would independently add stress exposure and reduce availability of coping resources. Overall, we found support for the theory, but also significant inconsistencies across the social strata we examined. Most importantly, we found no parsimony in social stress evidence, which should concern stress researchers seeking to improve predictions based on social stress theory, and could lead to articulation of better refined hypotheses.

With regard to sexual orientation minority status we found support for social stress theory only in measures of acute stressors. Compared with their heterosexual peers, LGBs were exposed to more acute stressors including prejudice-related life events. But the hypothesis was not supported in analyses involving chronic stressors among white LGBs. The findings regarding race/ethnic minority status were unequivocal and consistent with social stress predictions: they clearly showed that across a variety of stress measures, black and Latino LGBs were exposed to more stress and had fewer available coping resources than whites (both heterosexual and LGB). Furthermore, these findings showed that, as hypothesized, the excess in overall stress and chronic strain was accompanied by an increase in exposure to the prejudice-specific stressors. This suggests that the increase in overall stress exposure was related, at least in part, to prejudice-related events and conditions.

An important limitation concerns the study design, which did not include black and Latino heterosexuals. To study added burden by each of the social strata in the most economical way the study, which focused on LGB populations, was designed so that white heterosexual men were the reference group, with sexual minority status, race/ethnicity minority status, and female gender as added contrasts. The burden of race/ethnicity was conceptualized as a burden added to sexual orientation minority status across gender categories. Thus, we hypothesized that LGB black/Latino individuals would evidence greater stress than white LGB individuals (race/ethnicity variable added) and both groups would evidence greater stress than white heterosexuals (sexual orientation variable added).

Clearly, there is considerable prejudice toward black and Latino heterosexuals in our society, and research has shown that this is associated with greater exposure to social stressors including chronic and acute events and prejudice-related events (Kessler et al., 1999). Nevertheless, because we did not assess stress exposure of black and Latino heterosexuals, we are limited in our interpretation in that we cannot determine whether the effect seen for black and Latino lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals is greater than the effect we would have seen for black and Latino heterosexuals had they been included in the study. Our assumption at the outset has been that because of their sexual minority status, black and Latino LGBs would have greater exposure to stress than black and Latino heterosexuals in the same way that white LGBs would evidence greater exposure to stress than white heterosexuals. But we cannot verify this assumption.

A related limitation is that we cannot infer whether the black and Latino LGBs suffer from more stress than white LGBs because of greater homophobia in the black and Latino community or because of racism in the general community. Both hypotheses have been proposed (Cochran & Mays, 1994; Diaz et al., 2001; Mays, Cochran, & Rhue, 1993). Nonetheless, our study sheds some light on this question supporting the latter hypothesis: We found that black and Latino LGBs did not differ from white LGBs in exposure to prejudice related to their sexual identity but they did experience more prejudice due to their race/ethnicity.

The findings regarding gender were unequivocal, but they did not support the social stress model. Gender alone—that is, women as a group compared with men as a group—was not related to stress exposure in any of the measures we used. Indeed, contrary to the sociological stress model we tested, white heterosexual women had significantly fewer prejudice-related life events than white heterosexual men and, in the area of coping resources, they had larger social networks than the men.

General versus Prejudice-specific Stress

One advantage of this study is that we used measures that tap different aspects of the stress construct. This allows us to test how components of stress, specifically, prejudice-related versus general sources of stress, are distributed—something that has been lacking in the literature (Kessler et al., 1999). Consistent with social stress theory, we showed that sexual orientation and race/ethnic minority statuses are associated with an increase in overall stressors as well as exposure to the subset of prejudice-related stressors.

It is important to note, however, that our separation of the types of stressors is not perfect. Some of the stressors we called general are also likely to be related to prejudice. Measures of stress used in survey research typically tap experiential stressors—events and conditions that were experienced as stressful and are typically interpersonal (e.g., being attacked because of bias of the perpetrator, being discriminated against). But, as we noted in the Introduction, disadvantaged groups suffer also from structural stressors that are largely unidentified by such measures (Krieger, 2003; Meyer, 2003b). The general stress category captures some residuals of structural stressors, e.g., being fired from a job when the respondent had no knowledge that it was related to prejudice.

Another limitation of stress research is that in studying stress related to prejudice, researchers rely on the respondent’s judgment about whether an event occurred due to prejudice—we referred to these as subjective assessments. Such measures are biased because responses are related not only to the occurrence of the event, but also to other factors that affected its perception and reporting (Meyer, 2003a). To address this limitation in this study we employed a more objective assessment of stress along with the more subjective measures.

These and other problems make the classification of prejudice-related stress difficult (Schwartz & Meyer, 2006). It is a limitation of our study but is also a limitation of stress research in general. Researchers need to develop measures that capture some of the more distal prejudice-related stressors (Clark et al., 1999; Meyer, 2003a).

Gender and Stress

We concluded that there was no support for social stress theory regarding gender. This raises important questions about how we understand gender disadvantage. Specifically, is disadvantaged gender status similar to race/ethnicity and sexual orientation in terms of our discussion of prejudice and discrimination?

We found that although women are exposed to different types of stressors and coping resources than men, they have similar levels of overall stress, and do not have more stress related to prejudice than men. This should be considered in view of potential limitations in the study. Bias is possible, for example, if our measure of stress exposures underrepresented stressors that women are more likely to experience than men (Kwate, Davis, Hatch, & Meyer, 2006). Another limitation is that we used nonrandom sampling: it is possible that unknown selection bias led to a sample of women with less exposure to stress than the men. However, we do not believe that these are plausible explanations for our findings. First, our study included a more varied representation of the stress construct than most other studies, including measures that specifically inquire about gender-related prejudice. The consistency of our findings across measures suggests that further enrichment of the stress construct is not likely to change the results. Second, our study replicates previous research, including studies using random samples, suggesting a robust gender pattern (Hatch & Dohrenwend, in press; Kessler et al., 1999; Turner & Lloyd, 2004).

An interpretation that is consistent with these results is that gender has declined as an important category for social stratification (Goldin, 2006). This perspective invites us to consider that gender per se is not (or no longer) a category of relevance to understanding disadvantage in the area of stress. That is, that women, as a group, are not disadvantaged in the sense addressed by stress theory. Such a conclusion does not mean that women may not be disadvantaged in other ways and certainly it does not mean that gender does not matter, but it does mean that gender may not matter in the way that social scientists and health researchers have studied it for the past few decades; that it does not matter in the way that the predominant social stress models describe.

Moreover, even if women as a group are not exposed to more stress than men, it is plausible that some subgroups of women—poor women, black women, single mothers—are disadvantaged in very significant ways. Indeed, researchers using intersectionality approach have called for such specification in discussing social categories (Acker, 2000; Collins, 1998; Hancock, 2007; McCall, 2005; Schulz & Mullings, 2006). But if researchers move to an intersectionality perspective, it is important to note the shift in construct from gender (women vs. men) to intersectional gender categories (e.g., black single mothers). And it is important to indicate if the shift occurs because the new intersectional categories provide greater insight into stress or because the original category has declined in importance. Thus, even as stress researchers shift toward intersectional gender categories they should reflect on the state of the sociological categories on which theories and hypotheses were developed.

Conclusions Regarding Stress Theory and Health Disparities

Stress theory provides a useful approach to understanding the relationship between pervasive prejudice and discrimination and health outcomes, but predictions based on the theory need to be carefully investigated. A first step is to demonstrate that stress distribution is socially patterned, but this question has been largely overlooked by researchers. Our results regarding race/ethnicity and sexual orientation show that members of disadvantaged groups experience more stressors than members of advantaged groups. Of course, as we demonstrated in the introduction and in Figure 1, these results address only one element of the stress paradigm. Researchers need to evaluate these results in the context of patterns of disease outcomes (Schwartz & Meyer, 2006). It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore these issues, but we note that there are serious challenges to the stress paradigm in this area as well. For example, despite our and others’ findings that blacks experience more stress, recent studies have shown that, inconsistent with the stress hypothesis, they do not have higher rates of mental disorders than whites (Kessler et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2007) and indeed may fair better than whites in psychological well-being and self-esteem (Ryff, Keyes, & Hughes, 2003; Twenge & Crocker, 2002).

We provided both confirmation of and inconsistencies with stress theory expectations. A theory is strengthened not only by confirmations of its hypotheses but by attempts to falsify it (Platt, 1964). Ignoring negative results renders the theory un-falsifiable and therefore empirically weak. Further studies need to consider inconsistencies in the evidence regarding stress theory head on so that they can offer elaborations and further development of our understanding about the relationship between stress and health. As social scientists revisit conceptual elements of social stress theory, insights may be gained that would lead to new testable hypotheses and a better understanding of health disparities.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this paper was supported by am NIMH grant R01-MH066058. The authors thank Fred Markowitz, Suzanne C. Ouellette, and Carol S. Aneshensel for their insightful comments on an early version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr Ilan H. Meyer, Columbia University New York, NY UNITED STATES.

Sharon Schwartz, Columbia University, sbs5@columbia.edu.

David M. Frost, The City University of New York, DFrost@gc.cuny.edu.

REFERENCES

- Acker J. Rewriting class, race, and gender: Problems in feminist rethinking. In: Ferree MM, Lorber J, Hess BB, editors. Revisiting Gender. Walnut Creek, California: Altamira Press; 2000. pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Adams Paul L. Prejudice and exclusion as social traumata. In: Noshpitz JD, Coddington RD, Green MR, editors. Stressors and the adjustment disorders. Wiley Series in General and Clinical Psychiatry. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 362–391. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Kevin W. Stress and oppressed social category membership. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target's perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge: Massachusetts: Cambridge; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI. The structural contexts of sex differences in stress. In: Barnett RC, Biener L, Baruck GK, editors. Gender and stress. New York: Free Press; 1987. pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC. The sociology of mental health: Surveying the field. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of The Sociology of Mental Health. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Rutter CM, Lachenbruch PA. Social-structure, stress, and mental-health - competing conceptual and analytic models. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Baruch GK. Social roles, gender, and psychological distress. In: Barnett RC, Biener L, Baruch GK, editors. Gender and stress. New York: Free Press; 1987. pp. 122–143. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker R. Ethnicity without groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Depressive distress among homosexually active African-American men and women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:524–529. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Fighting words: Black women and the search for justice. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1998. What's going on? Black feminist thought and the politics of postmodernism; pp. 124–154. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In: Crenshaw KW, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K, editors. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. NY: New Press; 1996. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Deboeck P, Rosenberg S. Hierarchical classes model and data analysis. Psychometrika. 1988;53:361–381. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Jenne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty and racism on the mental health of Latino gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Theoretical integration. In: Dohrenwend BP, editor. Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 539–555. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP, Raphael K, Schwartz S, Stueve A, Skodol A. Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. New York: Free Press; 1993. The structured event probe and narrative rating method for measuring stressful life events; pp. 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler WW, Oths KS, Gravlee CC. Race and ethnicity in public health research: Models to explain health disparities. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2005;34:231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S. A queer encounter: Sociology and the study of sexuality. Sociological Theory. 1994;12:188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR, editors. Why are some people healthy and others not? The determinants of health of population. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CS. Network analysis and urban studies. In: Fisher CS, editor. Networks and places: Social relations in the urban setting. New York: The Free Press; 1977. pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn EN. The social construction and institutionalization of gender and race: An integrative framework. In: Ferree MM, Lorber J, Hess BB, editors. Revisiting Gender. Walnut Creek, California: Altamira Press; 2000. pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C. The rising (and then declining) significance of gender. In: Blau FD, Brinton MC, Grusky DB, editors. The declining significance of gender? New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gove WR, Tudor JF. Adult sex roles and mental illness. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:812–835. doi: 10.1086/225404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AI. Gay but not queer: Toward a post queer study of sexuality. Theory and Society. 2002;31:521–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM. When multiplication doesn't equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics. 2007;5:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: A review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z. (In press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC, Masten J, Goodkin K. Late middle-aged and older men living with HIV/AIDS: race differences in coping, social support, and psychological distress. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92:436–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB. Health inequalities among minority populations. The Journal of Gerontology. 2005;60B:63–67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Borenstein-Graves A, Haley WE, Small BJ, Mortimer JA. Determinants of a sense of mastery in African American and White older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S221–S224. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Wilkinson RG, editors. The society and population health reader: income inequality and health. New York: New York Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Prevalence and health implications of anti-gay discrimination: A study of black and white women and men in the CARDIA cohort. International Journal of Health Services. 1997;27:157–176. doi: 10.2190/HPB8-5M2N-VK6X-0FWN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: An eco-social perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:194–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwate NOA, Davis N, Hatch S, Meyer IH. What do we mean by racism? Conceptual and measurement issues in discrimination and stigma among African Americans. 2006 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont M, Molnar V. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Berndt A, Morris LM, Rose S. An empirical analysis of stressors for gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;42:63–88. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Griffin JL, Krowinski AC. Stressors for gay men and lesbians: Life stress, gay-related stress, stigma consciousness, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2003;22:716–729. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lopata HZ, Thorne B. Term Sex-Roles. Signs. 1978;3:718–721. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Dean L. Summary of measures: Mental health effects of aids on at-risk homosexual men. 1987 Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. Categorically unequal. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Depressive distress among homosexually active African American men and women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:524–529. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Rhue S. The impact of perceived discrimination on the intimate relationships of black lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 1993;25:1–14. doi: 10.1300/J082v25n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs. 2005;30(3):1771–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93:262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003b;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Greene B, Herek GM, editors. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 160–186. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Stall R, Pollack L, Paul JP, Binson D, Canchola J, et al. Health-related characteristics of men who have sex with men: a comparison of those living in "gay ghettos" with those living elsewhere. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:980–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan JJ, Akiyama Y, Berhanu S. The Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990: Developing a method for measuring the occurrence of hate violence. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;46:136–153. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of Different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. Structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The stress process revisited: Reflections on concepts and their interrelationships. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Platt JR. Strong inference. Science. 1964;146:347–353. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3642.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Enoch E, Johnston H, Rispel L. Social exclusion knowledge network (SEKN) scoping of SEKN and proposed approach. Submitted to the Commission on Social Determinants of HealthWorld Health Organisation by The Central Co-ordinating Hub for the SEKN. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, Carol D, Corey L, Keyes M, Hughes DL. Status inequalities, perceived discrimination, and eudemonic well-being: Do the challenges of minority life hone purpose and growth? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):275–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid TL, Horwitz AV. The social context of mental health and illness. In: Horwitz AF, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, Mullings L. Gender, race, class, & health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Meyer IH. Social stress theory and mental health disparities research: Conceptual and methodological considerations. 2006 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman S. Queer Theory Sociology. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stirratt MJ, Meyer IH, Ouellette SC, Gara M. Measuring identity multiplicity and intersectionality: Hierarchical classes analysis (HICLAS) of sexual, racial, and gender identities. Self & Identity. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Dimensions of life events that influence psychological 1istress: An evaluation and synthesis of the literature. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial research: Trends in theory and research. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 33–103. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Sociological approaches to mental illness. In: Horwitz AF, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. The stress process and the social distribution of depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:374–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: racial and ethnic contrasts. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:481–488. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Crocker J. Race and self-esteem: Meta-analyses comparing whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(3):371–408. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Rumbaut RG. Ethnic Minorities and Mental Health. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. The nature of stressors. In: Horwitz AF, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 176–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy societies: The afflictions of inequality. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors HH, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman MS, Jackson JS. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorders in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]