Abstract

We have assessed the clinical observation that the angle of the contralateral lamina matches the angle required from the sagital plane for the placement of pedicle screws in the subaxial cervical spine. Fifty-four randomly chosen axial CT scans taken between December 2003 and December 2004 were examined. Subjects were excluded if the scan showed signs of fracture, tumour or gross abnormality. The digitised images were analysed on the Philips PACS system using SECTRA software. One hundred and sixty-eight individual vertebrae were assessed between C3 and C7. The following were measured; the angle of the pedicle relative to the sagital plane, the smallest internal and external diameter of the pedicles and the angle of the lamina. Angular measures had a CV% of 3.9%. The re-measurement error for distance was 0.5 mm. Three hundred and thirty-six pedicles were assessed in 25 females and 29 males. Average age was 48.2 years (range 17–85). Our morphologic data from live subjects was comparable to previous cadaveric data. Mean pedicle external diameter was 4.9 mm at C3 and 6.6 mm at C7. Females were marginally smaller than males. Left and right did not significantly differ. In no case was the pedicle narrower than 3.2 mm. Mean pedicle angle was 130° at C3 and 140° at C7. The contralateral laminar angle correlated well at C3, 4, 5 (R2 = 0.9, C3 P = 0.002, C4 P = 0.06, C5 P = 0.0004) and was within 1° of pedicle angle. At C6, 7 it was within 11°. In all cases a line parallel to the lamina provided a safe corridor of 3 mm for a pedicle implant. The contralateral lamina provides a reliable intraoperative guide to the angle from the sagital plane for subaxial cervical pedicle instrumentation in adults.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Pedicles, Screws, CT

Introduction

The use of pedicle screws in the stabilization of the cervical spine was pioneered in Switzerland in the 1970s with the first reports of success published in the 1980s. Prior to this technique many other methods of posterior stabilization of the cervical spine had been used such as posterior plate and rod, lateral plate and screws and. wiring with varying results [10]. Of these techniques, transpedicular screw fixation offers the most superior pull out strength and biomechanical stability [2, 4, 7, 8], making it an attractive technique, however placement of these screws can cause damage to the adjacent neurovascular structures, namely the vertebral artery and spinal cord with potentially serious consequences.

There have been many studies that have attempted to identify the variable anatomy of the cervical pedicles in order to aid accurate and safe placement of transpedicular screws in the cervical spine [1, 11, 13, 15], as well as studies describing surgical techniques to aid screw placement [3, 9, 12]. As yet, no single method has proved to be 100% accurate or reliable.

In this study we have assessed the clinical observation, using digital CT images and PACS software, that the angle of the contra lateral lamina matches the angle required, from the sagital plane, for the placement of pedicle screws in the subaxial cervical spine. The understanding of the anatomy is fundamental to the safe application of this technique, which has very real risks of serious complications.

In order to add a level of safety to what is potentially a blind radiological technique, it is important to have knowledge of the available anatomical landmarks. This may aid the surgeon to assess whether to trust the trajectory suggested by the imaging, and to reference alignment off a reliable bony landmark, visible and already exposed within the operative field.

Materials and methods

A total of 54 axial CT scans, using a Litespeed VCT (GE Healthcare) scanner with a 0.625 mm slice thickness, were examined.

All images were randomly selected and accessed through the hospital PACS database from December 2003 to December 2004. Subjects who had evidence of fracture, neoplasm, infection or malformation were excluded. A single slice image of each vertebral level showing the pedicles at their largest diameter was selected. Any levels that were not clearly demonstrated, preventing us from measuring the pedicle width, were excluded (N = 0).

It must be noted that as the selection of the scans was random, not all levels i.e. C3–C7 were scanned in all patients.

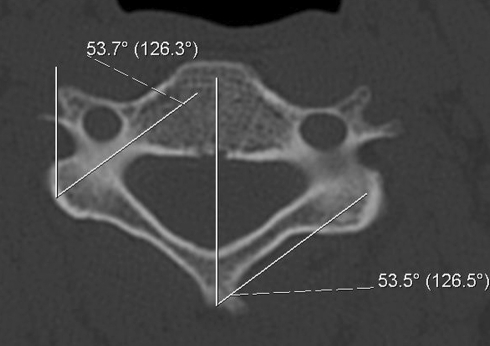

The following were measured; pedicle angle relative to the sagital plane (PA), laminar angle relative to the sagital plane (LA), maximum internal and external pedicle width (IPW, EXP) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Measurement of the pedicle and laminar angles, in the sagital plane, using the PACS goniometer. The angle is represented by the Fig. 3

All measurements were carried out with the digital Philips PACS system using the digital ruler and goniometer supplied with the SECTRA software (precision 0.1° and 0.1 mm). A single observer carried out all measurements. Means and standard deviations were calculated for all pedicle dimensions and reproducibility of these measurements was assessed in a subset of ten individuals with paired measures using the FDA approved formula for coefficient of variability (CV%). Statistics, (single tailed, equal variance Student’s t-test), were carried out using Microsoft Excel for Mac.

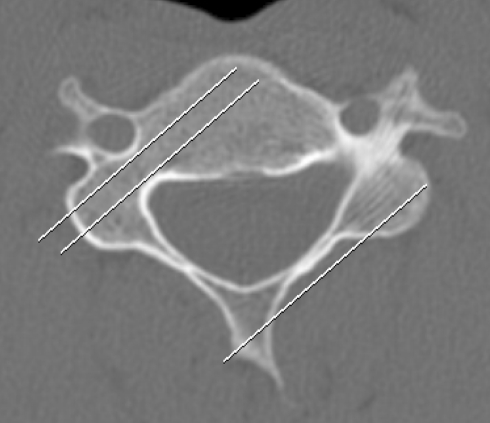

In a similar method used by Sakamoto et al. [1, 11, 13, 15], we constructed a 3 mm “digital screw” using the PACS software. This was then templated over the pedicles, parallel to the contra lateral lamina (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

“Digital screw” templating. The “screw is constructed of two parallel lines, 3 mm apart which run along the axis of the pedicle in the sagital plane, parallel with the contra lateral lamina. No breech of the cortex into either the foramen or canal is seen

We then assessed if the 3 mm digital screw breeched either cortex into the transverse foramen or spinal canal.

Results

In total 168 individual vertebrae (336 pedicles) were evaluated from C3–C7: means, ranges, and standard deviation were calculated.

Reproducibility studies confirmed a coefficient of variability (CV%)of 3.9% with respect to pedicle and lamina angles, and a re-measurement error of 0.5 mm with respect to the pedicle width.

The results are displayed in Table 1

Table 1.

Morphometric data

| Cervical level | Internal pedicle diameter | External pedicle diameter | Laminar angle | Pedicle angle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3 | Mean | 2.5 | 4.9 | 50.2 | 49.7 |

| Range | 1.5–3.6 | 3.2–6.0 | 41.3–56.6 | 43.3–56.4 | |

| SD | 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | |

| C4 | Mean | 2.7 | 5.1 | 50.5 | 50.3 |

| Range | 1.3–4.1 | 3.5–7.0 | 43.3–56.5 | 44.3–57.1 | |

| SD | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | |

| C5 | Mean | 3.3 | 5.6 | 50.5 | 50.1 |

| Range | 1.8–5.3 | 3.6–7.0 | 43.6–58.0 | 43.6–56.4 | |

| SD | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| C6 | Mean | 3.5 | 6.1 | 50.9 | 45.6 |

| Range | 1.7–5.5 | 4.0–8.6 | 39.3 | 31.6–53.9 | |

| SD | 0.8 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 5.6 | |

| C7 | Mean | 3.9 | 6.6 | 50.1 | 39.3 |

| Range | 2.4–5.5 | 5.0–10.5 | 39.3–60.1 | 28.2–56.5 | |

| SD | 0.6 | 0.2 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

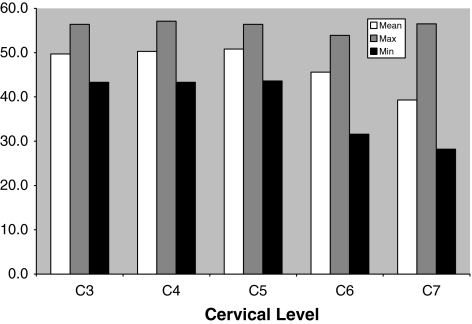

Mean angle of the pedicles

Mean pedicle angle remained constant at 50° from C3 (49.7)–C5 (50.1). The mean pedicle angle decreased from C6 (45.6)–C7 (39.3) There was no difference between male and female vertebrae (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pedicle angles

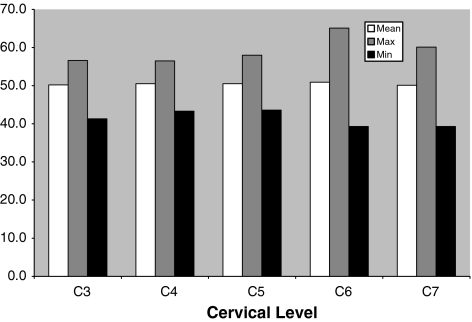

Mean angle of the laminae

Mean lamina angle remained constant at 50° from C3 (50.2) to C7 (50.1). There was no difference between male and female vertebrae (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Lamina angles

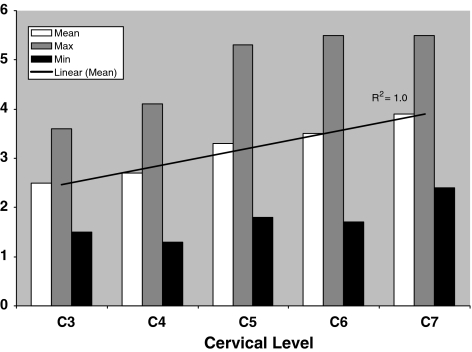

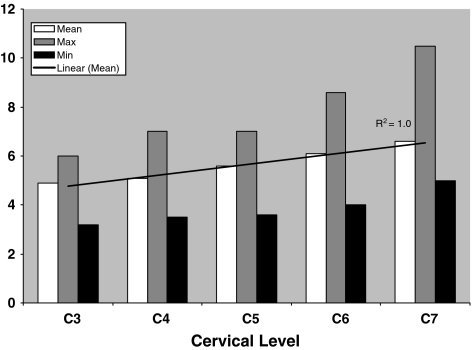

Mean internal and external pedicle diameter

Minimum internal pedicle diameter increased in a linear fashion (R2 = 1.0) from C3 (2.5 mm)–C7 (3.9 mm). No pedicle measured less than 1.3 mm. The measurements in male vertebra were consistently larger when compared to females (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Internal pedicle diameter

Minimum external pedicle diameter increased in a linear fashion (R2 = 1.0) from C3 (4.9 mm) C7 (6.6 mm).

No pedicle measured less than 3.2 mm. The measurements in male vertebra were consistently larger when compared to females (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

External pedicle diameter

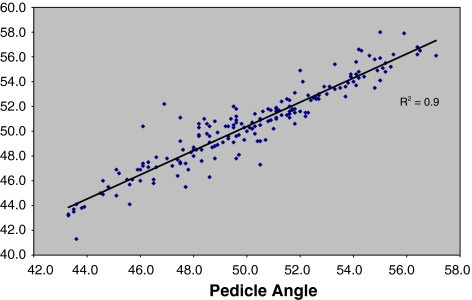

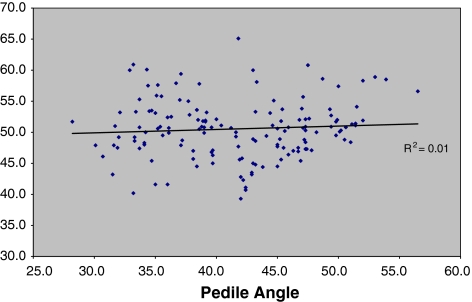

Comparison of pedicle angle with contra lateral lamina angle

From C3 to C5 there was a strong, statistically relevant correlation between the pedicle angle and the contra lateral laminar angle (R2 = 0.9, C3 P = 0.002, C4 P = 0.06, C5 P = 0.0004). All angles fell within 1° of each other (Fig. 7). This correlation was not seen from C6–C7 (R2 = 0.01) however; all angles fell within 11° of each other (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of pedicle angle with contra lateral lamina angles C3–C5

Fig. 8.

Comparison of pedicle angle with contra lateral lamina angles C6–C7

“Digital Screw” templating

When the 3 mm digital screw template was laid over the measured pedicles, parallel to the contralateral lamina, 100% of the screws lay within the pedicles with no evidence of breech into either the transverse foramen or spinal canal.

Discussion

Extensive studies have confirmed variability in cadaver morphometric measurement of the cervical pedicle anatomy and have suggested that all individuals undergoing posterior pedicle screw instrumentation should have a CT scan to identify the patient’s individual anatomy pre-operatively [5, 6, 10, 15].

As far as the authors are aware, this is the first CT-based anatomical study using digital images and a PACS system. Our results are similar to those of previous studies and confirm variability between both sexes and individuals, highlighting the importance of pre operative imaging. Differences in measurements may be due to racial variations and inconsistency when measuring the angles using visual best fit.

We agree with Sakamoto et al. [14], that safe trans-pedicular screw placement in the cervical spine depends on the selection of the entry point for screw insertion and on the correct orientation of the screw in the transverse plane, and our results confirm that the ideal angle for insertion of the screws should be 50°, as this correlates well with the pedicle angle from the sagital plane.

We also concur that the entry point for the screw should be as lateral as possible in the articular mass, in order to pass the screw through the centre of the pedicle and minimize the risk of pedicle breech.

From C3–C5, the angle of the pedicles to be instrumented were within 1° of the contralateral lamina at the same level, thus allowing the surgeon to use this as a reliable intraoperative guide to accurate screw placement.

There was little correlation between the angles at C6–C7, however when the digital screw template was applied parallel to the contralateral lamina at these levels there was still no breech of the pedicle walls, supporting the results of Sakamoto et al that the ideal and safe angle for screw insertion is 50°. Our study has confirmed that the lamina angles of the cervical spine remain constant, at 50° to the sagital plane from C3–C7.

There are limitations in using this technique: it only allows reference for the angle from the sagital plane, thus further techniques such as C-arm screening must be employed to confirm the correct positioning of the screws in both the sagital and coronal planes.

The technique is likely to prove of little use in cases where the anatomy of the posterior elements is abnormal due to revision fusion after a laminectomy or tumor destruction of posterior elements; however, the technique may prove particularly useful in ankylosing spondylitis where the facet anatomy may be distorted by the disease and fusion, but the anatomy of the posterior elements remains intact.

The authors stress that each individual cervical vertebrae should be assessed pre-operatively to ensure that there is no gross abnormality that may lead to mis-placement of the pedicle screws when using this, or any other technique. It is also imperative that meticulous detail to the point, of screw insertion, caudocranial direction of the screw and adequate C-arm guided radiography are employed.

From these results we conclude that the CT measurements in this radiographic, anatomical study suggest that the optimal screw insertion angle should be 50° in the sagital plane, and that using the contralateral lamina as an intra-operative guide to this angle may be a safe, simple and reliable adjunct when used in combination with radiological screening, of achieving this, reducing further, the variables encountered during this difficult technique. Further experimental, cadaveric studies are required to confirm the clinical reliability of this technique.

References

- 1.Bozbuga M, Ozturk A, Ari Z, et al. Morphometric evaluation of subaxial cervical vertebrae for surgical application of transpedicular screws. Spine Sep 1. 2004;29(17):1876–1880. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137065.62516.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaines R, Carson WL, Satterlee CC, Groh GI. Experimental evaluation of seven different spinal fracture internal fixation devices using nonfailure stability testing. The load-sharing and unstable-mechanism concepts. Spine. 1991;16:902–909. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaines R. The use of pedicle screw internal fixation for the operative treatment of spinal disorders. JBJS Oct. 2000;82-A:1458–1476. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones EL, Heller JG, Silcox DH, Hutton WC. Cervical pedicle screws versus lateral mass screws. Anatomic feasibility and biomechanical comparison. Spine. 1997;22:977–982. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karaikovic, et al (1997) Morphologic characteristics of human cervical pedicles. Spine 22:493–550. doi:10.1097/00007632-199703010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Karaikovic et al (2000) Surgical anatomy of the cervical pedicles: landmarks for posterior cervical pedicle entrance localization. J Spinal Disord 13(1):63–72 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kotani Y, Cunningham BW, Abumi K, McAfee PC. Biomechanical analysis of cervical stabilization systems. An assessment of transpedicular screw fixation in the cervical spine. Spine. 1994;19(22):2529–2539. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199411001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kothe R, Ruther W, Schneider E, et al. Biomechanical analysis of transpedicular screw fixation in the subaxial cervical spine. Spine. 2004;29(17):1869–1875. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137287.67388.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig et al (2000) Placement of pedicle screws in the human cadaveric cervical spine. Spine 25(13):1655–1667. doi:10.1097/00007632-200007010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Panjabi MM, et al. Internal morphology of human cervical pedicles. Spine. 2000;25(10):1197–1205. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panjabi MM, Manohar M, Shin EK, Chen NC Wang J-L(2000) Internal morphology of human cervical pedicles. Spine 25(10):1197–1205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Reinhold M, Magerl F, Rieger M, et al. Cervical pedicle screw placement: feasibility and accuracy of two new insertion techniques based on morphometric data. Spine J. 2007;16(1):47–56. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0104-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezcallah AT, Xu R, Ebraheim NA, Jackson T. Axial computed tomograpghy of the pedicle in the lower cervical spine. Am J Ortho . 2001;30(1):59–61. doi: 10.1007/s001320050574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto T, Neo M, Nakamura T. Transpedicular screw placement evaluated by axial computed tomography of the cervical pedicle. Spine. 2004;29(22):2510–2514. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144404.68486.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugur HC, Attar A, Uz A, et al. Surgical anatomic evaluation of the cervical pedicle and adjacent neural structures. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(5):1162–1169. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]