Abstract

A cross-sectional study targeted a total of 43,630 pupils in Niigata City, Japan was performed. The objective was to clarify the present incidence of low back pain (LBP) in childhood and adolescence in Japan. It has recently been recognized that LBP in childhood and adolescence is also as common a problem as that for adults and most of these studies have been conducted in Europe, however, none have so far been made in Japan. A questionnaire survey was conducted using 43,630 pupils, including all elementary school students from the fourth to sixth grade (21,893 pupils) and all junior high students from the first to third year (21,737 pupils) in Niigata City (population of 785,067) to examine the point prevalence of LBP, the lifetime prevalence, the gender differences, the age of first onset of LBP in third year of junior high school students, the duration, the presence of recurrent LBP or not, the trigger of LBP, and the influences of sports and physical activities. In addition, the severity of LBP was divided into three levels (level 1: no limitation in any activity; level 2: necessary to refrain from participating in sports and physical activities, and level 3: necessary to be absent from school) in order to examine the factors that contribute to severe LBP. The validity rate was 79.8% and the valid response rate was 98.8%. The point prevalence was 10.2% (52.3% male and 47.7% female) and the lifetime prevalence was 28.8% (48.5% male and 51.5% female). Both increased as the grade level increased and in third year of junior high school students, a point prevalence was seen in 15.2% while a lifetime prevalence was observed in 42.5%. About 90% of these students experienced first-time LBP during the first and third year of junior high school. Regarding the duration of LBP, 66.7% experienced it for less than 1 week, while 86.1% suffered from it for less than 1 month. The recurrence rate was 60.5%. Regarding the triggers of LBP, 23.7% of them reported the influence of sports and exercise such as club activities and physical education, 13.5% reported trauma, while 55.6% reported no specific triggers associated with their LBP. The severity of LBP included 81.9% at level 1, 13.9% at level 2 and 4.2% at level 3. It was revealed that LBP in childhood and adolescence is also a common complaint in Japan, and these findings are similar to previous studies conducted in Europe. LBP increased as the grade level increased and it appeared that the point and lifetime prevalence in adolescence are close to the same levels as those seen in the adulthood and there was a tendency to have more severe LBP in both cases who experienced pain for more than 1 month and those with recurrent LBP.

Keywords: Low back pain, Childhood, Adolescence, Cross-sectional study, Japan

Introduction

Among adults, it is well known that 70–80% of them experience low back pain (LBP) once in their lifetime and that LBP is a common condition with a high rate of occurrence in adults [2, 12, 16]. On the other hand, it has recently been recognized that LBP in childhood and adolescence is as common a complaint as that observed in adults. In addition, because the prevalence of LBP increases in adolescents as they progress to higher grade levels in school [7, 9, 19], to prevent LBP in adults, it is thus considered necessary to elucidate the actual conditions of LBP in childhood and adolescence [7, 10, 26]. However, most previous reports have been conducted in Europe, while few such reports have been published in Japan. The purpose of this study was to clarify the actual conditions of LBP in childhood and adolescence in Japan and to identify the risk factors for LBP using a large-scale cross-sectional epidemiological study based on a questionnaire administered to all children living in one area.

Materials and methods

The present study includes all schoolchildren, consisting of a total of 43,630 pupils (22,356 males and 21,274 females), including all elementary school students from the fourth to sixth grade (110 schools: 21,893 pupils) and all junior high students from the first to third year (57 schools: 21,737 pupils) in Niigata City (at longitude 139° east and latitude 37° north, located on the west coast of Japan with an area of 649 km2 and a population of 785,067 as of September 30, 2005). An anonymous questionnaire which were carefully protected any personal information was made and distributed to each school. In the Japanese school system, elementary school consists of a 6-year program including the first to sixth grades, while junior high school is a 3-year program comprising the first year, the second year and the third year levels. The fourth grade elementary school pupils thus correspond to children ranging form 9 to 10 years of age (E4), the fifth grade children ranging from 10 to 11 years of age (E5) and the sixth grade children ranging from 11 to 12 years of age (E6). The first year junior high school students correspond to children ranging from 12 to 13 years of age (J1), the second year students comprise children ranging from 13 to 14 years of age (J2) and the third year students including children ranging from 14 to 15 years of age (J3). The data were collected from October 17, 2005 to November 11, 2005. The questionnaire was taken home by all elementary school children to fill out together with their parents or guardians and thereafter they were collected at school. For junior high school students, it was filled out by each themselves and collected at school.

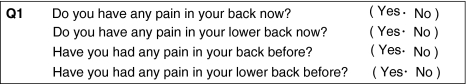

At first, basic information such as the name of their school, their grade, sex, height, and weight were filled in on the answer form. Next, any experience of LBP and back pain (BP) was described by means of multiple choice answers in Question 1 of the questionnaire (Fig. 1) with the options divided between the present and the past, and the details of LBP were continuously surveyed using the selection answer form for students who had experienced LBP and BP. In addition, regardless of the presence of LBP, the details of sports activities other than school physical education classes, musical activities, and social activities were reported in the questionnaire.

Fig. 1.

Details of Question 1 in the questionnaire

The definition of LBP judged by each student themselves as LBP and a valid response was the ones that had also appropriately answered Question 1.

Using this questionnaire, the point prevalence of LBP at the time of the study and the lifetime prevalence of LBP were evaluated and the gender differences, the age of first onset of LBP among third year junior high school students, the duration of LBP, the presence or absence of recurrent LBP, the trigger of LBP and the influence of sports and physical activities (the amount of time spent participating in athletic activities) among pupils with a lifetime prevalence were also evaluated.

In addition, the severity of LBP was divided into three levels (level 1: they had no limitation of any activity; level 2: they had to refrain from participating in sports and physical activities; and level 3: they had to be absent from school) to examine the factors that contribute to severe LBP (Original classification).

The SPSS software program (version 14) for Windows was used to perform a statistical analysis; the Chi-square test was used for comparisons between grades of the point prevalence and the lifetime prevalence of LBP, the gender differences of LBP and to check for the presence or absence of recurrent LBP; the Tukey–Kramer test was used for comparisons of the time spent participating in athletic activities between grades; and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine factors that contributed to severe LBP. In all the cases, significance was set at P < 0.05. In addition, all comparisons between grades were made between adjacent grades.

Results

Responses to the questionnaire were received from 34,830 of 43,630 pupils (response rate: 79.8%), and 34,423 pupils who were determined to have valid responses were thus analyzed (valid response rate: 98.8%).

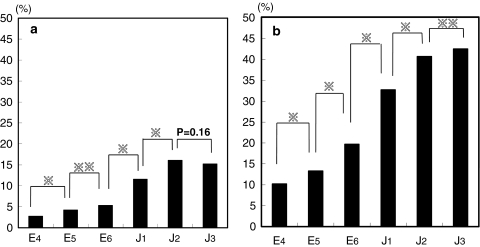

Among the 34,423 pupils with valid responses, 3,505 pupils (10.2%; 52.3% male and 47.7% female) had LBP at the time of the survey and 9,906 pupils (28.8%; 48.5% male and 51.5% female) had a history of LBP. To compare and investigate these findings by grade, both the point and lifetime prevalences were found to significantly increase with grade progression except for the findings between the second and third year of junior high school students regarding the point prevalence. In third year of junior high school students, a point prevalence was seen in 15.2%, while a lifetime prevalence was observed in 42.5% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

LBP in each grade. a The point prevalence of LBP: there were no significant differences between the second year and the third year of junior high school students regarding the point prevalence, but the point prevalence tended to be significantly higher as the grade level increased from the fourth grade onward (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.05), reaching 15.2% in the third year of junior high school students. b The lifetime prevalence of LBP: throughout all grades, the lifetime prevalence became significantly higher as the grade level increased (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.05), reaching 42.5% in the third year of junior high students

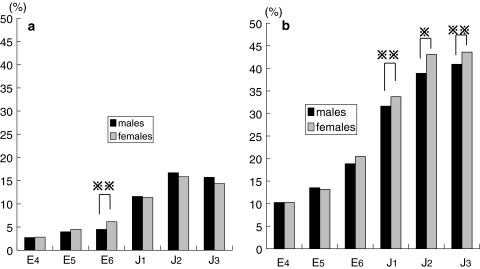

Regarding the gender differences, a point prevalence was seen in 10.1% of males and in 9.8% of females, a lifetime prevalence was seen in 29% of males and in 29.1% of females. To compare and investigate these findings by grade, there was less difference by gender according to the point prevalence, but it was significantly higher among females in the sixth grade elementary school students. There were no differences by gender in the lifetime prevalence from the fourth to sixth grade of elementary school students, but the rate was significantly higher among females in the first and third year junior high school students (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Gender differences of LBP in each grade. a The point prevalence of LBP: a point prevalence was seen in 10.1% of males and 9.8% of females. The difference was only significant for the sixth grade of elementary school students (**P < 0.05). b The lifetime prevalence of LBP: there were no differences between genders in elementary school students from the fourth to sixth grades, but from the first year onward the rate was significantly higher in females (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.05)

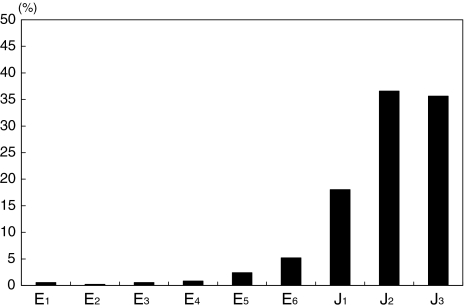

Regarding the age of first onset of LBP in third year junior high school students, a rapid increase was observed from the first year and thereafter, 90.2% of them experienced LBP during the first and third year of junior high school (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The age of first onset of LBP in third year junior high school students. About 90% of them experienced LBP during the first and third year of junior high school

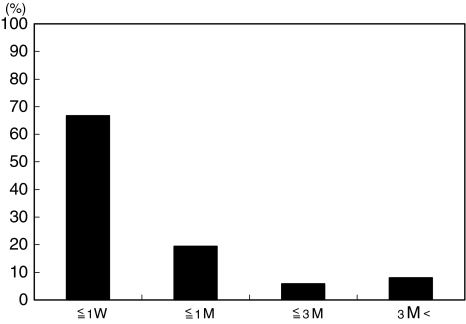

Regarding the durations of LBP, “shorter than 1 week” was the most common answer (66.7%), while “less than 1 month” accounted for 86.1% of all answers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The duration of LBP. A duration of shorter than 1 week was the most common, accounting for 66.7% of the total, and a duration of less than 1 month accounted for 86.1% of the total

As for the presence of recurrent LBP, 60.5% of the pupils had recurrent LBP with a lifetime prevalence. According to grade, the recurrence rate was considered to be quite high from the low grades (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The presence of recurrent LBP in each grade. Recurrence was found in 60.5% of the students with a lifetime prevalence of LBP, and the recurrence rate of LBP was high even in the lower grades

In regard to the triggers of LBP, “no triggers” was the most common answer (55.6%), while 23.7% answered “sports and exercises such as club activities and physical education” and 13.5% answered “burdens and injuries to the low back” region.

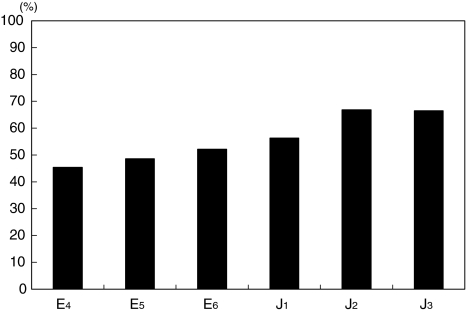

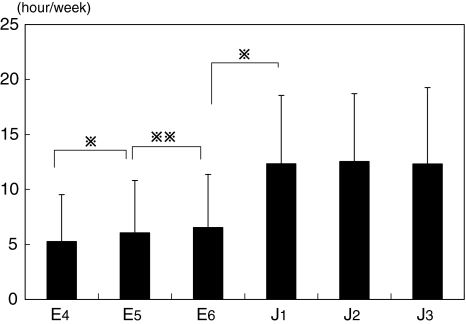

Until the first year of junior high school, the amount of time spent participating in sports activities significantly increased as the grade level increased, with an average 6.6 h/week for the sixth grade of elementary school students and 12.2 h/week for first year of junior high school students, thus indicating an approximately twofold increase between the two grades (Fig. 7). In addition, when the students were divided between those with a history of LBP (with LBP group) and those without a history of LBP (without LBP group) and their findings were compared, the amount of time spent participating in sports activities averaged 9.9 h/week in the group with LBP and 8.9 h/week in the group without LBP, thus indicating a significant increase in the group with LBP (P < 0.001; sex, age and BMI corrected).

Fig. 7.

The amount of time participating in sports activities for each grade. The amount of time participating in athletic activities significantly increased among students from the fourth of elementary school through the first year of junior high and progressively increased as the grade level increased (*P < 0.001, **P = 0.015), averaging 6.6 h/week for the sixth grade of elementary school students and 12.2 h/week for the first year of junior high school students, increasing approximately twofold between both grades

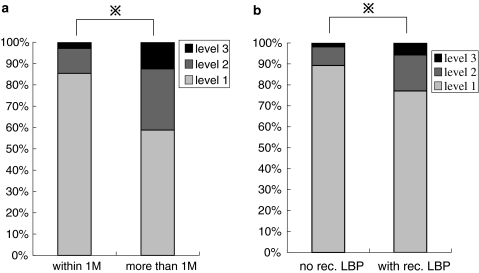

Moreover, as for the severity of LBP among pupils with a lifetime prevalence, level 1 accounted for 81.9%, level 2 for 13.9% and level 3 for 4.2%. When the duration of LBP was divided into “less than 1 month” and “more than 1 month,” the severity was significantly higher among those who answered “more than 1 month” (P < 0.001). Regarding the presence of recurrent LBP, the severity was also significantly higher among those with recurrent LBP (P < 0.001) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

The severity of LBP. a The duration of LBP: when the duration of LBP was divided into “less than 1 month” and “more than 1 month”, the severity of LBP was significantly higher in the group of with LBP of more than 1 month (*P < 0.001). b The presence of recurrent LBP: when the presence of recurrent LBP was divided into “without recurrent LBP” and “with recurrent LBP”, the severity was significantly higher in the group with recurrent LBP(*P < 0.001)

Discussion

In general, it has been recognized that LBP is a common condition with a high rate of occurrence among adults, and 70–80% of adults experience LBP at least once in their lifetime [2, 12, 16]. Walker [24] reported that over 80% of adults experienced LBP once in their lifetime and McCormic [15] reported that 7% of all adults visited their hospital every year with LBP. In addition, Walsh et al. [25] reported that the average lifetime prevalence of LBP was seen in 59% of British adults and the average point prevalence was seen in 14% of them. On the other hand, regarding LBP in children, it was previously believed that LBP in children was rare and only few cases needed to visit medical institutions with LBP and in such cases, sometimes severe diseases were revealed such as tumors and infections as well as disc disorders and spondylolysis. As a result, it was thought that LBP in children was thus an uncommon condition and was required close attention [23]. However, it has recently been revealed that LBP in children is as frequent a complaint as LBP in adults according to several recent reports [2, 3, 5, 11, 13, 18, 21, 26]. Using a cross-sectional study of 500 pupils between 10 and 16 years old in Northwest England, Jones et al. [11] determined the average lifetime prevalence of LBP to be 40.2%, while the average point prevalence was 15.5%, while 13.1% of them experienced recurrent LBP, and there was also a tendency to visit a medical practitioner and to have to refrain from participating in physical and sports activity and to be absent from school in cases who experienced recurrent LBP. In addition, Leboeuf-yde and Kyvik [13] performed a cross-sectional study of 29,424 twins ranging from 12 to 41 years of age in Denmark and thus reported the lifetime cumulative incidence to surpass 50% for 18-year-old females and in 20-year-old males.

As described earlier, most previous reports about LBP in children have been conducted in Europe and there are thus many unknown factors regarding the actual conditions of LBP among children in Japan. This study is a large-scale cross-sectional study using a questionnaire to evaluate approximately 40,000 pupils including all children from the fourth grade of elementary school through the third year of junior high school in Niigata City and it is believed that this study reveals the actual conditions of LBP among children in Japan. From this study, the average point prevalence of LBP at the time of the survey in the pupils from the fourth grade of elementary school through the third year of junior high school was seen in 10.2% and the average lifetime prevalence of LBP was 28.8%, and the prevalence significantly increased and the grade level increased, while the lifetime prevalence increased to up to 42.5% for the third year junior high school students. While no definite conclusions could be made as there has so far been only a small number of detailed reports on the frequency of LBP in childhood adolescence in Japan, as indicated by Harreby et al. [7], Hestbaek et al. [9], and Salminen et al. [19], it was estimated that the lifetime prevalence of LBP among children in Japan increased as the grade level increased and it also appeared that the lifetime prevalence in adolescence was gradually increasing and thus is expected to soon reach the same level as that observed in adulthood. In addition, regarding the severity of LBP, 81.9% of the students experiences LBP that did not require any particular restrictions, however, 13.9% required restrictions in regard to participation in both activities and physical education, while 4.2% had to be absent from school, as reported by Jones et al. [11]. In addition, the severity of LBP was more severe among children with long durations of LBP and children with recurrent LBP.

Regarding the risk factors of LBP, a large number of studies have been conducted to examine the gender differences [19], height and weight, body mass index [4, 8, 17], physical factors such as the mobility of the spinal column [4, 8, 28] and muscle strength [1, 5, 18, 19, 27], sports activities [2–5, 8, 10, 12, 19–21, 28], differences in lifestyles such as the amount of sedentary activity; how much time was spent sitting in chairs [2, 4, 10, 27], how long did they watch TV or play video games [2], mechanical load factors such as the weight of their school bags [10, 14, 20, 27], image findings such as X-rays [7] and MRI scans [19, 22], family histories [3, 7] and mental factors [3, 4, 8, 10, 20, 27], however, no definitive conclusion have yet been made.

In this study, we focused on sports activities as a risk factor for LBP in childhood and adolescence. As a result, the age of first onset of LBP increased rapidly from the first year of junior high school onward, and 90.2% of them experienced LBP during the first to third year of junior high school. In Japan, many children join club activities when they enter junior high school, and this study found that time spent participating in athletic activities increased approximately twofold from an average 6.6 h/week for the sixth grade of elementary school students to 12.2 h/week for the first year of junior high school students, thus demonstrating that the opportunities to participate in sports activities rapidly increased during this period. As for the triggers of LBP, 37.2% of them reported influences of external factors. A sum of 23.7% mentioned the influence of sports activities such as exercise, club activities, and physical education activities at school and 13.5% mentioned burdens and injuries to the low back occurring during regular daily activities, Moreover, when comparing the amount of time spent participating in athletic activities between students with a history of LBP (with LBP group) and those without a history of LBP (without LBP group), the amount of time spent participating in athletic activities averaged 9.9 h/week in the group with LBP and 8.9 h/week in the group without LBP, thus indicating it to be significantly greater in the group with LBP (P < 0.001). These findings suggested that the amount of time spent participating in athletic activities was one of the risk factors for the occurrence of LBP in childhood and adolescence.

Regarding the risk factors, this study examined the physical and sports activities only. As shown in previous reports [4, 6, 10], it is needless to say that the factors in the risk of LBP cannot be explained by a single cause and it is therefore necessary to evaluate other risk factors. In the future, we think that it will be necessary to survey other influences, especially the influence of mental factors in children [3, 4, 8, 10, 20, 27] as well as in adults and also investigate the clinical diagnoses made with imaging modalities [7, 19, 22] and thus make a prospective evaluation of LBP using longitudinal studies to clarify LBP in childhood and adolescence. Moreover, we also believe that these results may greatly help to elucidate various factors behind LBP in adults.

We conducted a large-scale cross-sectional study using a questionnaire to study the actual conditions of LBP among childhood and adolescence in Japan. The point prevalence of LBP was 10.2% of all pupils and the lifetime prevalence was 28.8%. Both prevalences increased as the grade level increased and the lifetime prevalence increased to up to 42.5% in the third year of junior high school students. The severity of LBP tended to be greater among children with long durations of LBP and children with recurrent LBP.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the members of the Niigata City board of education and others associated with the elementary schools and junior high schools in Niigata City for their valuable cooperation in making this study.

References

- 1.Anderson LB, Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C. Association between back pain and physical fitness in adolescents. Spine. 2006;31:1740–1744. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000224186.68017.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balagué F, Dutoit G, Waldburger M. Low back pain in schoolchildren. An epidemiological study. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1988;20:175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balagué F, Skovron ML, Nordin M, Dutoti G, Pol LR, Waldburger M. Low back pain in schoolchildren—a study of familial and psychological factors. Spine. 1995;20:1265–1270. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen JJ. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:429–438. doi: 10.1007/s005860050201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton AK, Clarke RD, McClune TD, Tillotson KM. The natural history of low back pain in adolescents. Spine. 1996;21:2323–2328. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199610150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardon G, Balagué F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in schoolchildren. What is the evidence? Eur Spine J. 2004;13:663–679. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0749-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsøe G, Kjer J. Are radiologic changes in the thoracic and lumbar spine of adolescents risk factors for low back pain in adults? Spine. 1995;20:2298–2302. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harreby M, Nygaard B, Jessen T, Larsen E, Storr-Paulsen A, Lindahl A, et al. Risk factors for low back pain in a cohort of 1389 Danish school children: an epidemiologic study. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s005860050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche CM. The course of low back pain from adolescence to adulthood. Eight-year follow-up of 9600 twins. Spine. 2006;31:468–472. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000199958.04073.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:312–316. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.056812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones MA, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan VB. A school-based survey of recurrent non-specific low-back pain prevalence and consequences in children. Health Educ Res. 2004;19:284–289. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelsey JK, White AA. Epidemiology and impact of low back pain. Spine. 1985;5:133–142. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO. At what age dose low back pain become a common problem? A study of 29, 424 individuals aged 12–41 years. Spine. 1998;23:228–234. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limon S, Valinsky LJ, Ben-Shalom Y. Children at risk. risk factors for low back pain in the elementary school environment. Spine. 2004;29:697–702. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000116695.09697.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormic A (1995) Morbidity statistics from general practice: fourth national study 1991–1992/a study carried out by the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, and the Department of Health. HMSO, London

- 16.Nachemson AL. The lumbar spine: an orthopaedic challenge. Spine. 1976;1:59–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197603000-00009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poussa MS, Heliövaara MM, Seitsamo JT, Könönen MH, Hurmerinta KA, Nissinen MJ. Anthropometric measurements and growth as predictors of low-back pain: a cohort study of children followed up from the age of 11 to 22 years. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:595–598. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0872-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salminen JJ, Pentti J, Terho P. Low back pain and disability in 14-year-old schoolchiidren. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81:1035–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salminen JJ, Erkintalo M, Laine M, Pentti J. Low back pain in the young. A prospective three-year follow-up study of subjects with and without low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:2101–2108. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szpalski M, Gunzburg R, Balagué Nordin M, Mélot C. A 2-year prospective longitudinal study on low back pain in primary school children. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:459–464. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taimela S, Kujala UM, Salminen JJ, Viljanen T. The prevalence of low back pain among children and adolescents. A nationwide, cohort-based questionnaire survey in Finland. Spine. 1997;22:1132–1136. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tertti MO, Salminen JJ, Paajanen HE, Terho PH, Kormano MJ. Low-back pain and disk degeneration in children: a case-control mr imaging study. Radiology. 1991;180:503–507. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.2.1829844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner PG, Green JH, Galasko CS. Back pain in childhood. Spine. 1989;14:812–814. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systemic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:205–217. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh K, Cruddas M, Coggon D. Low back pain in eight areas of Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:227–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, Taylor S, Symmons DPM, Silman AJ, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren: occurrence and characteristics. Pain. 2002;97:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, Taylor S, Symmons DPM, Silman AJ, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren: the role of mechanical and psychosocial factors. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:12–17. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widhe T. Spine: posture, mobility and pain. A longitudinal study from childhood to adolescence. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:118–123. doi: 10.1007/s005860000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]