Abstract

ELOVL4 was first identified as a disease-causing gene in Stargardt macular dystrophy (STGD3, MIM 600110.) To date, three ELOVL4 mutations have been identified, all of which result in truncated proteins which induce autosomal dominant juvenile macular degenerations. Based on sequence homology, ELOVL4 is thought to be another member within a family of proteins functioning in the elongation of long chain fatty acids. However, the normal function of ELOVL4 is unclear. We generated Elovl4 knockout mice to determine if Elovl4 loss affects retinal development or function. Here we show that Elovl4 knockout mice, while perinatal lethal, exhibit normal retinal development prior to death at day of birth. Further, postnatal retinal development in Elovl4 heterozygous mice appears normal. Therefore haploinsufficiency for wildtype ELOVL4 in autosomal dominant macular degeneration likely does not contribute to juvenile macular degeneration in STGD3 patients. We found, however, that Elovl4+/− mice exhibit enhanced ERG scotopic and photopic a and b waves relative to wildtype Elovl4+/+ mice suggesting that reduced Elovl4 levels may impact retinal electrophysiological responses.

Keywords: STGD3, Elovl4, knockout, mouse, ERG

1. Introduction

Stargardt macular dystrophy 3 (STGD3) is an autosomal dominant juvenile retinal disease characterized by progressive accumulation of lipofuscin, atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and degeneration of macular photoreceptors. Disease causing mutations have been identified in the elongation of very long chain fatty acid-4 (ELOVL4) gene. ELOVL4 is characterized by multiple putative membrane-spanning domains, a histidine cluster motif (HXXHH) involved in enzymatic activity (Fox, Shanklin, Ai, Loehr & Sanders-Loehr, 1994, Shanklin, Whittle & Fox, 1994), and an ER retention signal (Leonard, Bobik, Dorado, Kroeger, Chuang, Thurmond, Parker-Barnes, Das, Huang & Mukerji, 2000). The ELO family members are thought to be a part of a complex enzymatic system, which participate in the catalysis of reduction reactions occurring during fatty acid elongation (Cinti, Cook, Nagi & Suneja, 1992, Tvrdik, Westerberg, Silve, Asadi, Jakobsson, Cannon, Loison & Jacobsson, 2000).

Mutational analysis of the ELOVL4 gene in five large STGD-like macular dystrophy pedigrees revealed a 5 base-pair deletion, resulting in a frame-shift and the introduction of a stop codon, 51 codons from the end of the coding region (Zhang, Kniazeva, Han, Li, Yu, Yang, Li, Metzker, Allikmets, Zack, Kakuk, Lagali, Wong, MacDonald, Sieving, Figueroa, Austin, Gould, Ayyagari & Petrukhin, 2001). Subsequently, we identified two single base-pair deletions, 789delT and 794delT, in ELOVL4 in an independent large Utah pedigree, confirming the role of the ELOVL4 gene in a subset of dominant macular dystrophies (Bernstein, Tammur, Singh, Hutchinson, Dixon, Pappas, Zabriskie, Zhang, Petrukhin, Leppert & Allikmets, 2001). The 5 base-pair deletion and the two single base-pair deletions are predicted to result in a similarly truncated ELOVL4 protein. We next identified the Y270stop mutation, which generates a truncated ELOVL4 protein, in a Dutch family with dominant STGD (Maugeri, Meire, Hoyng, Vink, Van Regemorter, Karan, Yang, Cremers & Zhang, 2004). The mutations, identified to date, result in loss of the C-terminal dilysine motif encoding the putative ER retention signal (KXKXX). We and others have shown in cell transfection studies that these mutations result in loss of ER retention, and when cotransfected with wildtype ELOVL4, additionally alters localization of the wild type protein into nonER perinuclear aggregates (Grayson & Molday, 2005, Karan, Yang, Howes, Zhao, Chen, Cameron, Lin, Pearson & Zhang, 2005, Vasireddy, Wang, Huang, Vijaysarathy, Jablonski, Petty, Sieving & Ayyagari, 2005). We also generated several lines of 5bp ELOVL4 mutant transgenic mice. Corresponding to expression levels, these mice recapitulate major features of retinal pathogenesis in STGD3 patients showing lipofuscin accumulation, ERG abnormalities, and RPE and photoreceptor degeneration (Karan, Lillo, Yang, Cameron, Locke, Zhao, Thirumalaichary, Li, Birch, Vollmer-Snarr, Williams & Zhang, 2005).

Based on these findings, it is currently believed that ELOVL4 mutant proteins exert a dominant negative effect by sequestering and inhibiting wildtype ELOVL4 activity. However, it remains unclear, in vivo, as to whether a dominant negative effect from the mutant protein is solely responsible for degeneration or whether haploinsufficiency may contribute to retinal pathogenesis. To examine this mechanism, we generated Elovl4 knockout mice for functional consequences of Elovl4 loss in retinal development and early onset retinal degeneration. Here, we show that Elovl4−/− mice, while perinatal lethal, exhibit normal retinal development up to time of death at P0. Further, Elovl4 heterozygous mice do not exhibit retinal degeneration up to 11 months of age. The Elovl4+/− mice do, however, show enhanced ERG responses indicating that single gene expression may affect, to some extent, fully normal retinal function. These results further support in an animal model, that a dominant negative effect, rather than haploinsufficiency, is the primary mechanism of juvenile retinal degeneration in STGD3 patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Generation of Elovl4 KO mice

All animals were housed and handled in accordance with procedures provided by the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Elolv4 knockout mice were generated using a gene targeting approach. An arrayed 129/Sv BAC genomic library (Stratagene), was used to identify, by PCR, two BAC clones, 5E1 and 23D19, containing the mouse Elovl4 gene. By sequencing, we confirmed that the clone 5E1 contains Elovl4 and subsequently used the Not1 fragment for subcloning. By standard recombinant DNA methodologies, this subclone fragment and the pPTloxPneo plasmid (containing a loxP-flanked neomycin resistance cassette and pGK-tk cassette) were used to manufacture the knockout construct. The loxP-flanked neomycin resistance cassette was introduced into the second exon of Elovl4. The construct contains an approximate 2.5 kb short arm and a 4 kb long arm for recombination (Fig. 1). The construct was isolated by NotI digest and gel electrophoresis prior to transfection.

Figure 1.

Targeted mutagenesis of the Elovl4 gene. A. The targeting vector used for disrupting the endogenous Elovl4 gene. A pGKneo cassette flanked by loxP (open triangles) was inserted into exon 2 of a 15 Kb Elovl4 fragment. The disrupted Exon 2 construct is flanked by 2.5 kb short arm (B) and 4 kb long arm (A) sequences for homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Transcription directions of neo and tk are indicated by one way arrows. B. The endogenous gene. The direction of Elovl4 transcription is from left to right. C. The Elovl4 locus after homologous recombination. Arrows indicate primers used for PCR genotyping.

Mouse embryonic stem cells (containing the integrated Elovl4 KO construct) were injected into blastocysts harvested from C57BL/6 mice, followed by the surgical transfer of the blastocysts to pseudopregnant foster mothers. Germline transmission was determined by southern blot and PCR of DNA extracted from tail biopsies. For PCR genotyping, one set of primers were engineered to identify the introduced Neo cassette (Neo 5′-ATC GCC TTC TAT CGC CTT CTT GAC GAG TTC-3′) (Fig. 1), and the other primer set amplified undisrupted exon 2 of the endogenous Elovl4 gene (GWTF 5′-TGT AGC AGA CTG GCC GCT GAT-3′, GWTR 5′-CTC TGA AGA TGA AAA GGT TAA GCA-3′) (Fig. 1).

2.2. Generation of the YP2 polyclonal antibody

A well conserved (among mammals) hydrophilic sequence between amino acids 101 (Ser) to 162 (His) in ELOVL4 was used to generate the antibody. After expression in E.coli (BL21), the peptide was purified using a Ni-NTA spin column (Qiagen, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were generated and antisera affinity purified using antigen-conjugated columns (UltraLink Immobilization Kit, PIERCE). The polyclonal antibody was further purified using the method of Olmsted (Olmsted, 1986). Briefly, the ELOVL4 peptide was separated on SDS-PAGE along with pre-labeled protein standards, transferred onto Immobilon-P, and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). The membrane was incubated with the rabbit anti-sera and the region of the blot corresponding to the expected mobility of the ELOVL4-His tagged protein was excised. The YP2 antibody was eluted from the membrane strips in 0.2M glycine-HCL, pH 2.5 and then dialyzed against PBS overnight. The antibody was characterized using a combination of western blot and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

2.3. Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Eyes were dissected from adult Elovl4+/− and Elovl4+/+ mice and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1M PBS overnight at 4°C. The eyes were then cryoprotected in a graded series of sucrose/0.1M PBS (10–30%). Eyes were subsequently frozen in OCT compound and cryosectioned at 12μm in thickness. For embryonic day 18 (E18) Elovl4 mice, heads were removed, fixed, and prepared for cryosectioning as above.

Sections were incubated in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with the YP2 antibody, at approximately 3 ng/ml, overnight at 4°C. The monoclonal anti-mouse rod cyclic nucleotide gated channel alpha subunit (CNGCa1) (gift of Dr. Robert Molday), was diluted 1:100 for use. The sections were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit Texas Red or FITC- or goat anti-mouse FITC- conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour and coverslipped with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) containing propidium iodide (PI) to label cell nuclei. Images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

2.4. Western blot

Fresh bovine eyes were obtained from a local slaughterhouse and human donor retinal tissue from the Lion’s Eye Bank in Utah. Retinas were homogenized in lysis buffer 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.15 M NaCl, 0.001 M EDTA, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100. Ten μg of each protein lysate sample was run on 12% PAGE, transferred onto an Immobilon-P filter, blocked in dry milk, and incubated with the YP2 antibody. After washing, the filter was incubated in HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and ELOVL4 protein was detected with an ECL detection kit (Amersham).

2.5. RT-PCR

To determine if loss of the Elovl4 allele in Elovl4+/− mice may induces compensatory upregulated expression by the remaining gene, we performed RT-PCR to examine relative levels of Elovl4 RNA in these mice. We generated Elovl4 primers in separate exons (exons 2 and 6), ensuring intervening introns, for amplification of reverse transcribed RNA with expected amplicon size = 478 bp. Total RNA was extracted from Elovl4+/− and Elovl4+/− mouse retinas using conventional methods for Trizol reagent. One hundred ng total RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the Qiagen one-step PCR kit and Elovl4 specific primers (forward, 5′-ATG GTT TTG CTT AAC CT -3′, and reverse, 5′-TTG GGG AAG GGG CAG TC -3′). The GAPDH primer set (forward, 5′-AAA TGG TGA AGG TCG GTG TG -3′, and reverse, 5′-CAT GTA GAC CAT GTA GTT GAG -3′) was similarly used in parallel reactions from each retinal RNA sample. Five μl volumes were collected from each reaction at 5 cycle intervals between 20 and 35 cycles of amplification. At the completion of the PCR reaction, the aliquots were run on an agarose gel and ethidium bromide stained bands were examined by densitometry on an Eagle Eye II gel documentation system. Relative Elovl4 levels were normalized to GAPDH signals.

2.6. Electroretinograms

After overnight dark adaptation, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (16 mg/kg), and the pupils dilated with 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine HCl. Mice were placed on a heating pad. ERGs were recorded with a gold wire loop, making contact with the corneal surface through a layer of 1% methylcellulose. Needle electrodes placed in the cheek and tail served as reference and ground leads, respectively. Responses were amplified (2–10000 Hz), averaged, and stored using a PC-based signal averaging system with custom software. Flash stimuli were presented in a ganzfeld bowl. Dark-adapted responses were obtained to strobe flashes covering a 5-log unit intensity range (log −2, −1, 0, +1, and +2 cds/m2). Cone-mediated responses were obtained to stimuli superimposed on a steady rod-desensitizing adapting field (50–75 fL). The major ERG components were analyzed conventionally. The amplitude of the dark-adapted ERG a-wave was measured from the baseline to the a-wave trough. The amplitude of the dark- and light-adapted b-wave was measured from the trough of the a-wave to the b-wave peak or, if no a-wave was present, from the baseline to the b-wave peak. Implicit times reflect the time elapsed between stimulus presentation and the a-wave trough or the b-wave peak. Adjusted a-wave ERGs were generated by plotting amplitude responses (μV) at 7msec after flash. This timepoint corresponds to a more pure photoreceptor response, unmodified by the b-wave which may affect the trough a-wave amplitude.

2.7. Fatty acid Analysis

Embryonic day 19 mice were used for FA analysis. Five hundred μl of blood were collected from each mouse and frozen at −80°C. Red blood cells were analyzed according to the method by Lagerstedt et al. (Lagerstedt, Hinrichs, Batt, Magera, Rinaldo & McConnell, 2001) using capillary gas chromatography with electron-capture negative-ion mass spectrometry (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). Fatty acid-pentafluorobenzyl esters were analyzed using an AT-Silar-100 capillary column (Alltech Assoc. Inc, Nicholasville, KY). Each fatty acid was matched to a labeled internal standard of closest chain length, retention time, and concentration. Individual lipids are expressed as a percentage of the total lipid analyzed.

2.8. Statistics

Errors are expressed as standard errors of the mean (SE). Comparisons between two different groups for the Elovl4+/− and Elovl4+/+ ERGs and embryonic weights were measured using the Student’s t test. Lipid statistical analysis was done using SPSS’s independent sample’s t-test (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The probability level at which the null hypothesis was rejected was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Elovl4 knockout mice are perinatal lethal

Mouse embryonic stem cells containing the integrated Elovl4 construct (Fig. 1) were injected into blastocysts harvested from C57BL/6 mice, followed by the surgical transfer of the blastocysts to the uterine horns of pseudopregnant foster mothers. We identified chimeric mice in which the ES cells have contributed to the mouse by visual inspection (these mice exhibited bicolored coats). Germline transmission was determined by the presence of agouti in the offspring. We used the C57BL/6 strain for backcross since they are well-characterized, tend to be physically and reproductively robust, and are free of retinal degeneration. Germline transmission was determined from Southern blot and PCR analysis of DNA extracted from tail biopsies. PCR based genotyping included primers which identify a sequence from the Neo cassette (Fig. 2) and the undisrupted endogenous allele was identified with a primer set corresponding to exon 2 of the Elovl4 gene.

Figure 2.

Identification and characterization of Elovl4 mice. A. Genotypes determined by PCR amplification of DNA extracted from tail biopsies. The upper band is generated when the endogenous Elovl4 gene is present, and the lower band from the disrupted gene. The left lane shows Elovl4+/+ genotype, the middle lane shows Elovl4+/−, and the right lane represents Elovl4−/− genotyping reactions. B. Size comparison of embryonic day 18 Elovl4+/+, Elovl4+/−, and Elovl4−/− littermates. C. Mean weight differences are shown for Elovl4 knockout pups vs. wildtype and heterozygous pups. D. RT-PCR results show that Elovl4 RNA levels are reduced by 46% in Elovl4+/− mice relative to wildtype mice. GAPDH amplification signals used for normalization between retinal samples. N=4

Elovl4−/− mice were born with an expected Mendelian frequency, yet they died shortly after birth. Upon processing of embryos for cryostat sectioning, we found that the E18 Elovl4−/− pups were consistently smaller than Elovl4+/− and Elovl4+/+ littermates (Fig. 2). We weighed 3 litters of pups from E18 timepoints, and found that the Elovl4−/− pups were 13.1% smaller (or 86.9% the size of the other pups in the litters) on average (p<0.001) than the Elovl4+/− or Elovl4+/+ pups (Fig. 2, Table 1). The overall appearance of Elovl4−/− pups was essentially normal except for shortened forelimbs and thinner, less opaque, skin relative to heterozygous and wildtype littermates.

Table 1.

Elovl4 Embryonic Day 18 Group Weight Statistics

| Genotype | N | Mean | Std Deviation | Std Error | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ & +/− | 11 | 1.0521 | .05299 | .01598 | ||||

| −/− | 4 | .8588 | .05255 | .02627 | ||||

| Independent Samples Test | ||||||||

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||

| F | Sig | t | df | Sig (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std Error Difference | Lower | Upper |

| * .008 | .930 | 6.322 | 13 | .000 | .19522 | .03088 | .12851 | .26193 |

| ** | 6.349 | 5.407 | .001 | .19522 | .03075 | .11793 | .27251 | |

Equal variances assumed

Equal variances not assumed

We next examined Elovl4+/− mice for altered Elovl4 RNA levels relative to that of wildtype mice. Total RNA was extracted from Elovl4+/− and Elovl4+/+mouse retinas and used for RT-PCR analysis. We found that Elovl4 RNA levels are reduced by 46% in the Elovl4+/− mice (Fig. 2D). Although protein levels were not directly examined, these results suggest that there may be a reduction in Elovl4 levels in the heterozygous mice.

3.2 ELOVL4 antibody characterization

The ELOVL4 fusion protein was expressed in E. coli and purified using a Ni-NTA spin column prior to injection into rabbits. Serum was collected and purified using the method of Olmsted (Olmsted, 1986). This antibody was characterized by western blot and immunohistochemistry using lysates from E. coli, bovine, human, and mouse retinal tissues (Fig. 3). ELOVL4 bands on western blots were effectively eliminated by preabsorption of the YP2 antibody with the peptide prior to incubation with blots (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Western blotting using the YP2 (ELOVL4) antibody. A. YP2 recognizes the His-Elovl4 fusion protein expressed in bacterial lysates. B. Human and bovine retinal lysates showing ELOVL4 protein detection with the YP2 antibody and effective loss of signal with ELOVL4 protein preabsorption.

ELOVL4 immunolabeling, using the YP2 antibody, was obvious in human retinas within the inner segments (IS) of both rod and cones, synaptic termini of the outer plexiform layer (OPL), cells of the inner nuclear layer (INL), and the ganglion cell layer (GCL) (Fig. 4A). This immunolabeling profile is similar to previously reported ELOVL4 staining in human retinal tissue (Grayson & Molday, 2005). The YP2 immunolabeling pattern in adult mouse retina was similar to that in the human retina (Fig. 4A, B), and staining within the retina was absent when antibody was preabsorbed with the protein prior to IHC (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

ELOVL4 immunolabeling in human and mouse retinal sections. ELOVL4 signal is green in all figures. A. Normal 27 yr old human retina showing that the YP2 antibody immunolabels photoreceptor inner segments (IS) (short arrow- cone IS, long arrow- rod IS), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and cells within the inner nuclear layer (INL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL). Cell nuclei are labeled with PI (red). B. A similar immunolabeling profile is evident in adult mouse retina. C. Preabsorption control in mouse retina. D-F. Embryonic day 18 retinas from Elovl4 +/+ (D), Elovl4 +/− (E), and Elovl4 −/− (F) mice immunostained with the YP2 antibody.

3.3 Histology and immunohistochemistry in embryonic and adult Elovl4 mice

Based on perinatal lethality, embryonic day 18 Elovl4−/− mice were collected and compared, by histological and immunocytochemical analyses, to Elovl4+/+ and Elovl4+/− littermates, for alterations in retinal development. In both Elovl4+/+ and Elovl4+/− E18 mice, immunolabeling was apparent in the GCL, cells in the neuroblast layer, and the developing photoreceptor IS region (Fig. 4D, E). The profile of Elovl4 immunolabeling within the embryonic retina was similar to results from previous studies using in situ hybridization in embryonic and postnatal mouse retinas (Zhang, Yang, Karan, Hashimoto, Baehr, Yang & Zhang, 2003). KO embryos showed no Elovl4 immunoreactivity (Fig. 4F) using the YP2 antibody. At E18, knockout mice showed no difference in ongoing organization and approximately equivalent cell numbers measured by PI nuclear staining within the retinal layers (data not shown).

Elovl4+/− mice showed relatively normal retinal development, adult architecture, and Elovl4 immunolabeling relative to wildtype mice (Fig. 5). Often, the outer segments of 11 month old Elovl4+/−mice appeared somewhat less organized and slightly shorter than age-matched wildtype mice (Fig. 5B). However, at this age the ONL layer thickness was equivalent to age-matched normal mice.

Figure 5.

Retinal sections from Elovl4 +/+ (A) and Elovl4 +/− (B) 11 month old mice. Nuclei are stained with PI and outer segments are labeled with a CNGCa1 antibody (green). Retinal layers are normal in the Elovl4 +/− retina. Arrows indicate some disorganization in the outer segments.

3.4 ERG analysis

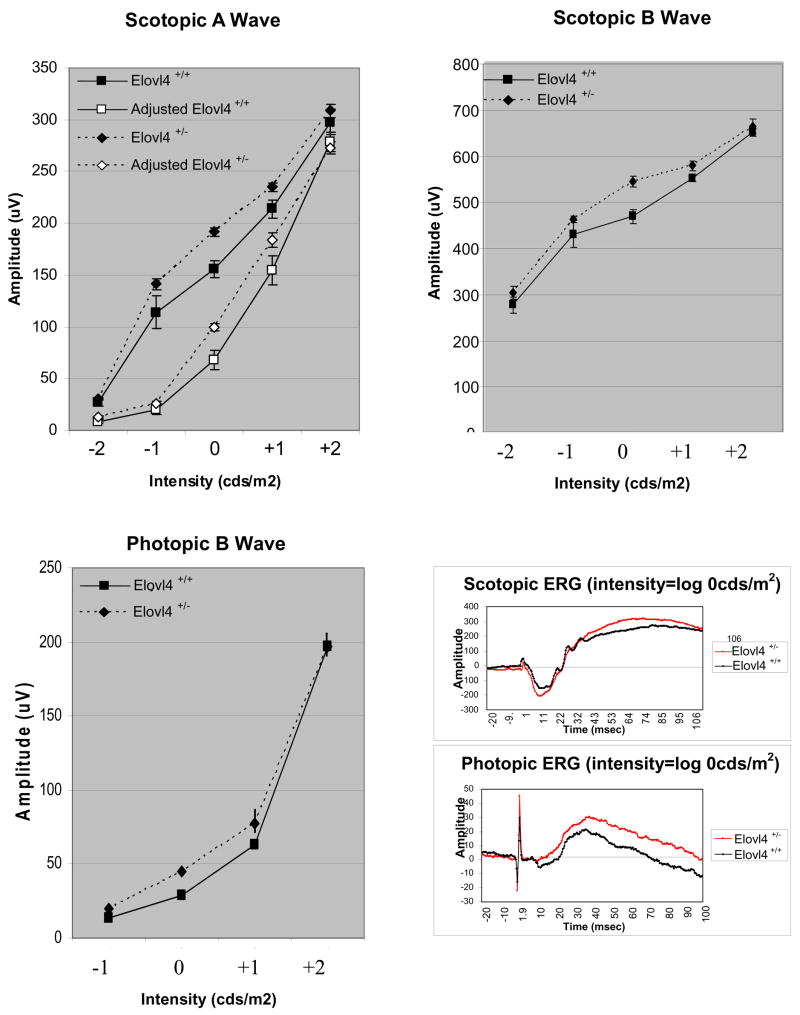

We examined the mice for altered retinal function using ERG at 9 months of age. Elovl4+/− mice showed a tendency for enhanced mesopic ERG responses relative to age-matched wildtype mice between log 0 cds/m2 and log +1 cds/m2 flash intensities (Fig. 6). Statistically significant differences were found in dark adapted mice at a stimulus intensity of log 0 cds/m2 for the scotopic a-wave (Fig. 6, Table 2). When we adjusted the scotopic a-wave to show photoreceptor responses at 7msec after the light pulse, the Elovl4+/− mice continued to exhibit significantly increased values within the log 0 to +1 cds/m2 range. Scotopic b-wave responses, while not statistically significant, also showed a tendency in this range towards amplified responses. Elovl4+/− mice also showed an enhanced photopic b-wave which was statistically significant at log 0 cds/m2. These data suggest that Elovl4+/− mice show slightly altered ERG responses within a defined region of light intensities.

Figure 6.

Nine month old Elovl4+/+ and Elovl4+/− mice scotopic and photopic single flash ERG responses. The scotopic a and b waves were measured at intensities log −2, −1, 0, +1, and +2 cds/m2. The filled symbols show trough a wave amplitude values (μV), and the open symbols represent the (adjusted) a wave values at 7msec after light flash. The dark line with squares represent the mean Elovl4+/+ amplitude responses in μV (N=5) and the dashed line with diamonds represent the mean Elovl4+/− (heterozygous) mouse responses (N=11). Note that in both sets of scotopic a wave plotted values the heterozygous mice show a tendency for enhanced responses at mesopic intensities. The scotopic b wave shows a similar enhanced response, although not significant) at log 0 cds/m2. The Elovl4+/− mice also show significantly enhanced photopic b wave amplitude at log 0 cds/m2. Representative scotopic and photopic ERG traces (at intensity = log 0 cds/m2) are shown in the lower right corner.

Table 2.

ERG amplitude differences between Elovl4+/−and Elovl4+/+ mice at 9 months of age. Shaded blocks show t-test significance at P≤ 0.05.

| Elovl4+/−: Elovl4+/+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity (log cds/m2) | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Scotopic A | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.27 |

| Adjusted Scotopic A | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.49 |

| Scotopic B | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.37 |

| Photopic B | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.50 | |

3.5 FA levels in red blood cells (RBCs)

ELOVL4 is proposed to play a role in long-chain fatty acid elongation. Since the amount of tissue in the embryonic mouse retina is insufficient for these studies, we compared the RBC membrane fatty acid profiles between normal, Elovl4+/−, and Elovl4−/− mice. RBC membrane fatty acid content has been previously used as a marker for systemic and retina fatty acid levels (Hoffman & Birch, 1995). Elovl4−/− mice showed an increase in poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) compared to normal controls (Fig. 7). The increase in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) the end product of omega-3 PUFA synthesis, was of particular interest since DHA has been shown to be essential for normal retinal development (Anderson, Connor & Corliss, 1990, Bazan, 1989). However, the precursor to DHA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), was significantly decreased in the RBC lipid membranes of the Elovl4−/− mice (Fig. 7). Elovl4+/− mice exhibited intermediate but generally not significantly different levels in PUFA classes (Fig. 7) relative to Elovl4−/− and control mice.

Figure 7.

Analysis of lipid differences in RBCs from Elovl4+/+ and Elovl4−/− mice. Elovl4−/− mice show a significant increase in DHA, C24:2, and Adrenic acid levels, and decreased EPA levels compared to normal controls. Elovl4−/− mice also show increased levels of C25:1 and C26:2. The inset table shows corresponding p-values and percent changes in Elovl4−/− fatty acid levels compared to normal controls. (Control n=4, Elovl4+/− n=5, Elovl4−/− n=3)

4. Discussion

Stargardt macular dystrophy 3 (STGD3), an autosomal dominant juvenile retinal degeneration, is induced by mutation of one copy of the ELOVL4 gene. Current evidence suggests that the mutant 5bp ELOVL4 deletion exerts a dominant negative effect over that of the remaining wildtype allele. It is not currently clear whether the mutant ELOVL4 protein induces retinal degeneration in human patients through an unidentified “gain of function” activity or through elimination of wildtype protein activity due to loss of ER localization and function. In previous cell culture studies, several independent laboratories reported that all disease-causing ELOVL4 mutations, identified to date, bind and sequester the wildtype protein in nonER localized aggregates. This would, in effect, cause a functional loss of normal ELOVL4 activity. In addition, misfolding of the mutant protein could induce the ER uncoupled protein response thereby impacting cell viability. Karan et al. recently showed upregulation of UPR proteins and induction of apoptosis in HEK293 cells transfected with ELOVL4 mutants (Karan, Yang, Howes, Zhao, Chen, Cameron, Lin, Pearson & Zhang, 2005b).

We previously generated transgenic mice expressing the human ELOVL4 5bp deletion mutant. Based on expression level of the transgenes, the mouse lines generated in the previous study exhibited varying rates of retinal degeneration in the presence of the endogenous murine Elovl4 genes. While these mice verified the effect of the human ELOVL4 mutation, it was not possible to examine the consequences of loss of a functional Elovl4 gene vs. the role of ELOVL4 mutants on retinal pathogenesis. In this study, we generated mice incorporating a targeted deletion of the Elovl4 coding region to examine the impact of Elovl4 loss on retinal status.

The smaller overall size and lethality of Elovl4−/− (knockout) mice supports an essential requirement for Elovl4 in normal development. While exhibiting slight structural abnormalities in forelimb and skin development, the overall retinal architecture at embryonic day 18 appeared relatively normal. Based on previously reported Elovl4 expression in the brain, it is possible that abnormal development of the CNS may account for the lethality of these mice. Preliminary studies, however, have so far not shown any obvious histological abnormalities in the brain.

In this study we show that Elovl4+/− mice, although exhibiting reduced wildtype Elovl4 RNA levels, exhibit relatively normal photoreceptor development and no apparent photoreceptor degeneration up to eleven months of age. We show that Elovl4 heterozygosity is not sufficient to induce an early onset photoreceptor degeneration and, therefore, haploinsufficiency is likely not the mechanism governing retinal degeneration in Stargardt patients. However, the Elovl4+/− mice exhibited a small but significant enhancement of scotopic and photopic ERGs, suggesting that wildtype levels of Elovl4 may be required for normal ERG responses. This effect on ERG responses was particularly significant with log 0 cds/m2 flash intensities. While reduction in Elovl4 is not sufficient to induce retinal degeneration, the results from these studies suggest an unidentified effect on retinal physiology.

Increased DHA levels in the RBCs in Elovl4−/− mice is a surprising result since it is the end product of omega-3 lipid biosynthesis and has been a candidate substrate or product for Elovl4 function in retina and brain. Other significant PUFA pathways such as the omega-6 pathway also showed increases in C22 unsaturated lipids similar to DHA. Based on the general increase in C22 lipids it would appear that Elovl4 activity impacts, directly or indirectly, this step of FA synthesis.

Loss of Elovl4 results in embryonic lethality and disruption of one gene does not result in compensatory upregulation of RNA levels by the remaining functional gene. Assuming protein levels are reduced and, coupled with the differences in ERGs described in this study, suggest that development or maintenance of retinal function may be affected in Elovl4+/− mice. Elovl4 knockout mice are currently being examined for cause of lethality. These studies should provide important new information concerning the role of ELOVL4 in development and broaden our understanding of ELOVL4 function.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Knights Templar Eye Research Foundation (GK, ZY), and the following grants (to KZ): NIH (R01EY14428, R01EY14448); the Ruth and Milton Steinbach Fund, Ronald McDonald House Charities, the Macular Vision Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson GJ, Connor WE, Corliss JD. Docosahexaenoic acid is the preferred dietary n-3 fatty acid for the development of the brain and retina. Pediatr Res. 1990;27(1):89–97. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199001000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG. The metabolism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the eye: the possible role of docosahexaenoic acid and docosanoids in retinal physiology and ocular pathology. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;312:95–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein PS, Tammur J, Singh N, Hutchinson A, Dixon M, Pappas CM, Zabriskie NA, Zhang K, Petrukhin K, Leppert M, Allikmets R. Diverse macular dystrophy phenotype caused by a novel complex mutation in the ELOVL4 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(13):3331–3336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti DL, Cook L, Nagi MN, Suneja SK. The fatty acid chain elongation system of mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Prog Lipid Res. 1992;31(1):1–51. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(92)90014-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox BG, Shanklin J, Ai J, Loehr TM, Sanders-Loehr J. Resonance Raman evidence for an Fe-O-Fe center in stearoyl-ACP desaturase. Primary sequence identity with other diiron-oxo proteins. Biochemistry. 1994;33(43):12776–12786. doi: 10.1021/bi00209a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson C, Molday RS. Dominant negative mechanism underlies autosomal dominant Stargardt-like macular dystrophy linked to mutations in ELOVL4. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(37):32521–32530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DR, Birch DG. Docosahexaenoic acid in red blood cells of patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36(6):1009–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karan G, Lillo C, Yang Z, Cameron DJ, Locke KG, Zhao Y, Thirumalaichary S, Li C, Birch DG, Vollmer-Snarr HR, Williams DS, Zhang K. Lipofuscin accumulation, abnormal electrophysiology, and photoreceptor degeneration in mutant ELOVL4 transgenic mice: A model for macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(11):4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407698102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karan G, Yang Z, Howes K, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Cameron DJ, Lin Y, Pearson E, Zhang K. Loss of ER retention and sequestration of the wild-type ELOVL4 by Stargardt disease dominant negative mutants. Mol Vis. 2005;11:657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerstedt SA, Hinrichs DR, Batt SM, Magera MJ, Rinaldo P, McConnell JP. Quantitative determination of plasma c8-c26 total fatty acids for the biochemical diagnosis of nutritional and metabolic disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;73(1):38–45. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard AE, Bobik EG, Dorado J, Kroeger PE, Chuang LT, Thurmond JM, Parker-Barnes JM, Das T, Huang YS, Mukerji P. Cloning of a human cDNA encoding a novel enzyme involved in the elongation of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 3):765–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugeri A, Meire F, Hoyng CB, Vink C, Van Regemorter N, Karan G, Yang Z, Cremers FP, Zhang K. A novel mutation in the ELOVL4 gene causes autosomal dominant Stargardt-like macular dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(12):4263–4267. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted JB. Analysis of cytoskeletal structures using blot-purified monospecific antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 1986;134:467–472. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)34112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanklin J, Whittle E, Fox BG. Eight histidine residues are catalytically essential in a membrane-associated iron enzyme, stearoyl-CoA desaturase, and are conserved in alkane hydroxylase and xylene monooxygenase. Biochemistry. 1994;33(43):12787–12794. doi: 10.1021/bi00209a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvrdik P, Westerberg R, Silve S, Asadi A, Jakobsson A, Cannon B, Loison G, Jacobsson A. Role of a new mammalian gene family in the biosynthesis of very long chain fatty acids and sphingolipids. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(3):707–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasireddy V, Wang XF, Huang J, Vijaysarathy C, Jablonski M, Petty HR, Sieving PA, Ayyagari R. 5-Bp-Deletion Mutant ELOVL4 Protein Causes Altered Localization of the Wild Type ELOVL4 Protein in COS-7 Cells- Probable Mechanism Underlying Stargardt’s-Like Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(5):1643. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Kniazeva M, Han M, Li W, Yu Z, Yang Z, Li Y, Metzker ML, Allikmets R, Zack DJ, Kakuk LE, Lagali PS, Wong PW, MacDonald IM, Sieving PA, Figueroa DJ, Austin CP, Gould RJ, Ayyagari R, Petrukhin K. A 5-bp deletion in ELOVL4 is associated with two related forms of autosomal dominant macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):89–93. doi: 10.1038/83817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Yang Z, Karan G, Hashimoto T, Baehr W, Yang XJ, Zhang K. Elovl4 mRNA distribution in the developing mouse retina and phylogenetic conservation of Elovl4 genes. Mol Vis. 2003;9:301–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]