Abstract

Monosomy 1p36 is a subtelomeric deletion syndrome associated with congenital anomalies presumably due to haploinsufficiency of multiple genes. Although immunodeficiency has not been reported, genes encoding costimulatory molecules of the TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) are within 1p36 and may be affected. In one patient with monosomy 1p36, comparative genome hybridization and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed that TNFRSF member OX40 was included within the subtelomeric deletion. T cells from this patient had decreased OX40 expression after stimulation. Specific, ex vivo T cell activation through OX40 revealed enhanced proliferation, and reduced viability of patient CD4+ T cells,providing evidence for the association of monosomy 1p36 with reduced OX40 expression, and decreased OX40-induced T cell survival. These results support a role for OX40 in human immunity, and calls attention to the potential for haploinsufficiency deletions of TNFRSF co-stimulatory molecules in monosomy 1p36.

Keywords: OX40, 4-1BB, TNFRSF superfamily, 1p36, T cell memory, primary immunodeficiency, subtelomeric deletion

Introduction

Monosomy 1p36 is a relatively common subtelomeric deletion syndrome presumably caused by haploinsufficiency of a number of different genes. The deletions are variable in size and location within chromosome 1p36 and may consist of terminal deletions, interstitial deletions, derivative chromosomes or complex rearrangements [1]. The syndrome occurs in 1:5000 births and is characterized by a phenotype including deep-set eyes, midfacial hypoplasia, asymmetric ears and pointed chin. Other clinical associations may include seizures, hypothyroidism, cardiomyopathy, developmental delay, hearing impairment and mental retardation [2,3,4,5]. To date, immunodeficiency has not been reported in these patients, however genes for various immunologically important members of the TNFR superfamily are located in or near the region of 1p36.

At least five genes encoding tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily (SF) members co-localize to chromosome 1p36, including OX40 (CD134, TNFRSF4), glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family-related gene (GITR, TNFRSF18, AITR), herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM, TNFRSF14), 4-1BB (CD137, TNFRSF9), and CD30 (Ki-1,TNFRSF8) [1,6,7]. The TNFRSF family is comprised of a diverse array of genes that provide costimulatory signals to achieve optimal T cell activation, proliferation, survival and longevity [6,7]. Of particular interest to this study is OX40; a TNFRSF family member which is proposed to be a key costimulatory molecule involved in the generation of memory CD4 T cells [8,9]. OX40 is induced after ligation and activates NF-κB to promote expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins survivin, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, thus prolonging effector T cell survival and increasing the memory T cell pool [10–15]. OX40 also functions in T cell-dependent B cell proliferation and differentiation, implicating its role in generating optimal IgG memory recall responses to foreign antigens. As an inducible costimulatory molecule, OX40 is suggested to be more important in regulating the secondary immune response when compared to constitutively expressed molecules like CD28 that are crucial for inducing primary responses. OX40 is preferentially expressed on activated CD4 T cells, and its absence or blockade results in decreased CD4 T cell viability, defective maintenance of CD4+ memory and an inability to generate an appropriate immune response to foreign antigen [16,11,17,18,19,12,20]. Furthermore, OX40 deficient mice exhibit reduced CD4+ responses to LCMV, VSV, contact hypersensitivity and common protein antigens. This is presumably due to decreased antigen specific T cells, generated late in the primary response as well as five weeks later when the memory response is formed [9,11–17,21–24]. In addition, reverse signaling through OX40L induces B cell proliferation, differentiation and immunoglobulin secretion [25,26].

In this report we describe a 3-year-old female with an abnormal karyotype and subtelomeric deletion in chromosome 1p36. This patients’ particular deletion included OX40 and was associated with a specific decrease in CD4+ effector cell viability and an accelerated proliferation profile as measured by carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution. This is the first study showing functional differences in T cell proliferation and viability in a human haploinsufficient for OX40.

Materials and Methods

Patient evaluation

The patient and was evaluated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and permission to obtain peripheral blood as well as report data was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board for the protection of human subjects. Consent for participation in this report was provided by the patient’s parents or by the appropriate individual in the case of control donors. Clinical laboratory measurements were performed using standard techniques in a CLIA certified laboratory.

Array CGH (Comparative Genome Hybridization)

Microarray analysis was performed by Signature Genomic Laboratories (Spokane, Washington), using the Signature Chip, (www.signaturegenomics.com), which included assessment of 622 loci using 1887 BAC clones and DNA extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the patient. The analysis was performed using previously published methods [27].

Cytogenetic and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Analyses

Metaphase chromosomes were obtained from phytohemagglutinin (PHA) - stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes and G-banding was performed by standard methods. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were carried out to define the extent of the 1p deletion. Commercially available probes for the subtelomeric regions of chromosome 1 (TelVysion 1p, CEB108/T7 and TelVysion 1q) were used on metaphase chromosomes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vysis, Inc. Downer’s Grove, Ill). BAC clone (RP5-902P8,) was selected from the public databases to confirm deletion of the OX40 gene. The map position of each BAC clone was determined according to the UCSC Human Genome Project (May 2004 assembly) (http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu). All BAC clones were obtained through CHORI BACPAC Resources (Oakland, CA). BAC DNA was isolated (Puregene, Gentra System) and labeled by nick translation (Nick Translation Reagent Kit, Vysis, Inc.) in the presence of Spectrum Red (Vysis, Inc.). FISH probes were hybridized to metaphase preparations overnight; slides were then washed and counterstained with DAPI using standard protocols [28].

In vitro polyclonal stimulation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patient or adult control donors were processed from whole blood by Ficoll-hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) and were used immediately in experiments, or cryopreserved in 10% DMSO with 90% FCS or Human AB serum for future studies. PBMCs from normal donor controls were obtained from the Human Immunology Core at the University of Pennsylvania. For evaluations of TNFRSF expression, PBMC were studied directly after isolation or cells were stimulated for 18 hours in RPMI containing 10% heat inactivated FCS and 2µg/ml PHA. After stimulation, the cells were washed three times in PBS with 1% BSA, and stained for flow cytometry analysis using monoclonal antibodies to CD3, CD4, OX40 (CD134), GITR and CD154 (CD40L). For proliferation and viability studies, PBMCs were thawed and labeled with fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) in a final concentration of 5µM (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). K562-based artificial antigen presenting cells (CD32 aAPCs) engineered to express the Fc receptor CD32 and 4-1BBL or OX40L were prepared and loaded with anti-CD3 (OKT3, Orthoclone) and co-cultured with PBMCs as previously described [29–31]. Cells were enumerated on a Coulter Multisizer 3 (Beckman Coulter). Proliferation and cell viability were assessed by CFSE dilution and Viaprobe (7-AAD) staining respectively, using flow cytometry. All antibodies used were obtained as direct fluorophore conjugates from BD Biosciences and staining procedures were followed according to the manufacturer. Cells were acquired using a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) and data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc).

Relative CFSE Preservation index

Dilution of CFSE on day 6 of stimulation was calculated for the CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells activated with anti-CD3 loaded K562 aAPCs expressing costimulatory molecules OX40L or 4-1BBL. Mean Fluorescent Intensity (MFI) of CFSE expression was measured by using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc.) and relative CFSE preservation of expression was calculated for the patient and each normal donor from the following equation: MFI of CFSE anti-CD3+costimulatory molecule ÷ MFI of CFSE anti-CD3 alone. Averages of the relative values were calculated for conditions receiving 4-1BBL costimulation or OX40L costimulation from both the normal donor controls and patient.

Statistics

A two-tailed, student t-test was performed to compare values obtained from the patient and the normal donors. p values < 0.05 (*) and/or < 0.001 (**) were considered statistically significant as indicated in the appropriate figure legends.

Results and Discussion

Clinical history

Our patient was a 3 year old female with abnormal karyotype and subtelomeric deletion syndrome consistent with monosomy 1p36. Her clinical course included hyperinsulinism with resulting hypoglycemia, hearing loss, apnea requiring tracheostomy, multiple infections, and episodes of septicemia (Table 1). Her immunologic evaluation demonstrated low post-immunization titers against pneumococcal conjugate vaccination and decreased tetanus toxoid-specific antibody titer despite making an initial response. In addition, she demonstrated low tetanus- and absent Candida-induced lymphocyte proliferation (Table 2). Other immune parameters evaluated were generally within normal ranges including: quantitative immunoglobulins, mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation, quantitative lymphocyte subsets and leukocyte nitroblue tetrazolium reduction. Together these results could suggest imperfect maintenance of immunological responses, however her recurrent episodes of bacteremia might also have contributed. She was treated with IVIG for her poor specific antibody for several months, but died from septicemia.

Table 1.

Documented Clinical Infections*.

| Age | Infections | |

|---|---|---|

| 10.5mo-15mo | • | Parainfluenza type 3 |

| • | Rotavirus | |

| 35–38 months | • | Multiple episodes of bacteremia/sepsis (P. aeruginosa, P. putida, Alcaligenes, Xanthomonas, S. aureus, Klebsiella) |

| • | Pneumonia (Klebsiella) | |

| • | Recurrent pulmonary infiltrates and right sided consolidation | |

| • | Groin abscess (Klebsiella, α-Strep) | |

| • | Tracheitis (P. aeruginosa and putida) | |

Confirmed by viral culture, cultures of blood, sputum, or wound. Patient had central line at 18months, tracheostomy at 34months complicating assessment of immunodeficiency due to inherent increased risk of infection with implanted medical devices.

Table 2.

Immunologic evaluations.

| Immune Parameter | 38 – 40 months | Reference Range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Leukocytes, (cells/µL) | 15,200 | 5000–15000 | |||||

| % | cells/µl | cells/µl | |||||

| Neutrophils | 64 | 9728 | >1000 | ||||

| Lymphocytes | 30 | 4560 | 1700–6900 | ||||

| HUMORAL IMMUNITY | |||||||

| Quantitative Immunoglobulins | |||||||

| IgG, (mg/dL) | 4581 | 9084 | 477 – 1334 | ||||

| IgA, (mg/dL) | 401 | 22–159 | |||||

| IgM, (mg/dL) | 791 | 47–200 | |||||

| IgE, (IU/mL) | 4.51 | 0.19–16.9 | |||||

| Qualitative IgG | |||||||

| Tetanus titer (IU/mL) | 1.271 | 0.371,2 | > 0.1 | ||||

| Diphtheria titer (IU/mL) | 0.471, | > 0.1 | |||||

| Pneumococcal serotypes, | 0/7 serotypes in conjugate vaccine, | > 1.0 µg/mL3 | |||||

| (µg/mL) | (0/14 serotypes tested) 1, | ||||||

| Varicella Ab | 0.165 | > 0.60 | |||||

| CELLULAR IMMUNITY | |||||||

| Lymphocyte Subset Analysis | cells/µl | % | cells/µl | cells/µl | |||

| CD3+ | 70 | 3192 | |||||

| CD3+/CD4+ | 1719 | 52 | 2371 | 500 – 2400 | |||

| CD3+/CD8+ | 470 | 17 | 775 | 300 –1600 | |||

| CD19+ | 27 | 1231 | 200 – 2100 | ||||

| CD3−/CD16+/CD56+ | 3 | 137 | 100 – 1000 | ||||

| CD4+/CD45RA+ | 44 | 2006 | |||||

| CD4+/CD45RO+ | 10 | 456 | |||||

| Lymphocyte Proliferation | CPM | CPM | |||||

| Candida (cpm) | 421 | Cntrl 20387 | |||||

| Tetanus (cpm) | 3674 | Cntrl 65782 | |||||

| PHA (cpm) | 311215 | Cntrl 377817 | |||||

| Con A (cpm) | 179255 | Cntrl 254756 | |||||

| PWM (cpm) | 136473 | Cntrl 166838 | |||||

| INNATE IMMUNITY | |||||||

| CH50 | 208units | 101– 300 units | |||||

| NBT test | Normal | ||||||

Pre Immunoglobulin Replacement

Protective titer waned in 2 months time

In light of prevnar immunization, would expect 7 serotypes to be >1.0 µg/mL

Post Immunoglobulin Replacement

No clinical varicella and no vaccine

Characterization of terminal 1p36 deletion

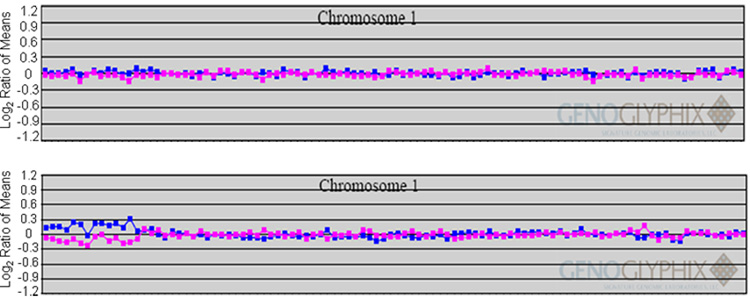

On G-banding analysis a small, subtelomeric deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1 was identified in 17/20 cells studied. Three cells had an apparently normal female karyotype. FISH using subtelomeric probes for 1p and 1q confirmed the deletion to be mosaic, present in 17/20 cells (Figure 1b, Left). Mosaicism has been previously described in 1p36, and these patients have been shown to manifest the clinical features of the 1p36 deletion syndrome [1]. The patient’s clinical history of recurrent infections and immunodeficiency characterized by impaired memory recall responses led us to inquire whether the deletions included genes responsible for the immunodeficiency. The telomeric region of 1p36 contains several immunologically important members of the TNFRSF that likely arose from genetic duplication and have distinct, but related roles in the co-stimulation of T cells [6,32]. The relative locations of these genes are shown in Figure 1a. GITR and OX40 are found approximately one megabase from the telomere, while the loci for other TNFRSF members HVEM, 4-1BB and CD30 are located between 2–12 megabases from the telomere. A probe including the OX40 locus, BAC RP5-902P8, was used in FISH studies and was present on only one copy of chromosome 1, demonstrating haploinsufficiency for the region containing this gene (Figure 1b. Middle). Given that our patient was haploinsufficient for OX40, and OX40 has been previously determined to participate in immunological memory in murine studies, we sought to investigate the effects of this haploinsufficiency on T cell proliferation and viability. Hybridization of this BAC to both chromosomes in two other 1p36 deletion syndrome patients (data not shown) suggested that the deletion of this region is not a uniform feature of the disease. Array CGH was used to further map the breakpoint of the deletion using a targeted BAC array containing multiple clones representing this chromosomal interval. The array detected a single copy loss of 13 BAC clones at the subtelomeric region of chromosome 1p36. The apparent mosaicism resulted in detection slightly below the standard confidence since presumably the presence of cells containing 2 normal copies of chromosome 1p within the DNA led to decreased detection (Figure 1c). Despite the contribution of normal cells, the proximal boundary of this deletion was mapped on the array between clones RP5-907A6 (deleted) and RP11-33E3 (not deleted) indicating an approximately 2.9-3 Mb terminal deletion of 1p36 which includes the OX40 gene. Parental chromosomes were analyzed, and neither parent was found to carry a 1p deletion. This de novo deletion is mosaic, and not present in all cells tested, it is presumed to have arisen mitotically, early in development.

Figure 1. FISH analysis and microarray profile define the 1p deletion.

a. Map of chromosome 1p36 demonstrating the location of TNFRSF members and BAC probes used to define patient deletion. The deletion breakpoint is marked. b. FISH studies on metaphase spreads from the patient. (Left) Subtelomeric probes for 1p - CDB108/T7 labeled in green, and 1q - 1qtell9 labeled in red, reveal a deletion of the 1p probe. (Middle) BAC RP5-902P8 includes the OX40 locus and is present in only one copy of chromosome 1, demonstrating deletion of this locus. (Right) BAC RP4-758J18, which maps proximal to the OX40 locus, within 1p36 is present on both copies of 1p. c. Microarray profile for a mosaic, terminal deletion of 1p36 characterized by array CGH. Each clone represented on the array is arranged along the x-axis according to its location on the chromosome with the most distal/telomeric p-arm clones on the left and the most distal/telomeric q-arm clones on the right. The blue line plots represent the ratios from the first slide for each patient (control Cy5/patient Cy3) and the pink plots represent the ratios obtained from the second slide for each patient in which the dyes have been reversed (patient Cy5/control Cy3). Typical deletions show deviations greater than 0.3 and -0.3. (top) Plot for a normal chromosome 1 showing a ratio of 0 on a log2 scale for all clones. (bottom) Plot showing single-copy loss of 13 clones at 1p36.3 indicating a terminal deletion of 2.9Mb. Note that for most of the clones the deviations do not reach the expected 0.3 and -0.3 because of the presence of mosaicism.

Expression of OX40 on PBMC and T cells

To evaluate whether the deletion of the 1p36 region resulted in decreased expression of TNFRSF members, including OX40, freshly isolated PBMC from the patient and normal controls were stimulated overnight with PHA. CD40L (CD154), encoded by a gene located on the X chromosome and not affected by the 1p36 deletion, was induced at similar levels in CD4+ T cells from both the patient and a normal donor by flow cytometry and was used as control (Figure 2, left). Expression of GITR, also included in the deletion, was slightly decreased relative to control (Figure 2, middle). The most striking difference, however, was the reduced expression of OX40 on the patient’s CD4+ T cells compared to normal control expression (Figure 2, right).

Figure 2. Decreased expression of OX40 on patient PBMC compared to healthy control.

PBMC from patient or normal donor control were stimulated with PHA and IL-2 overnight and surface expression was measured for CD40L, GITR and OX40. Histograms represent expression of these costimulatory receptors on patient CD4+ T cells (black) compared to isotype (gray) and normal donor control (heavy black).

CD4+ T cell proliferation and viability

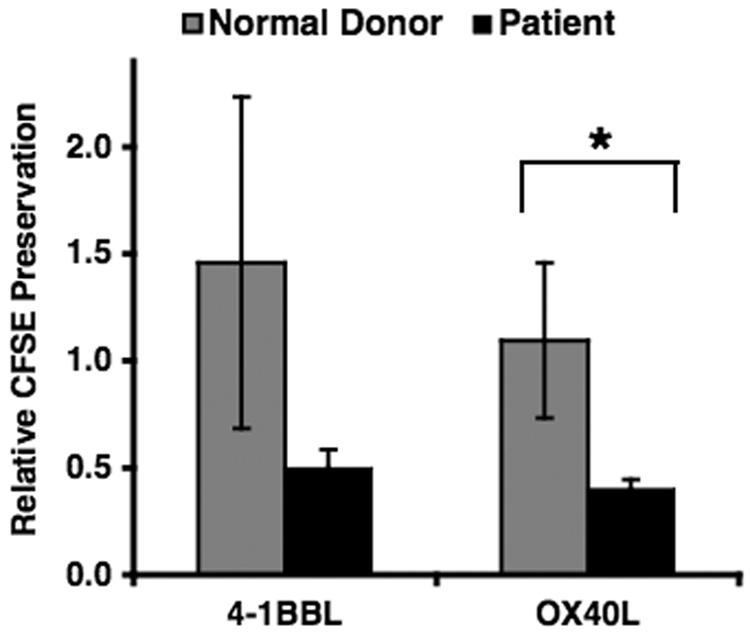

OX40 is known to play an important role in the costimulation of CD4 T cells resulting in increased survival and improved memory responses. To determine whether the decreased expression of OX40 observed in the patient had an effect on the survival or proliferation kinetics of CD4+ T cells, K562-based artificial antigen presenting cells (aAPCs) expressing OX40L or 4-1BBL were used to provide costimulation to patient and donor control cells. The aAPC system employed has been previously shown to support anti-CD3 mediated polyclonal T cell expansion and survival in vitro [29,33]. Using this system, we observed enhanced proliferation of the patient’s CD4+ T cells when compared to normal controls (Figure 3A). Stimulation by anti-CD3 alone resulted in similar kinetics, with fully diluted CFSE for both patient and control, suggesting proliferation of the entire population within 6 days of stimulation. Proliferation of normal control cells stimulated with additional costimulatory signals OX40L or 4-1BBL appeared to occur more slowly than in patient cells, quantified in Figure 3B. The difference in CFSE dilution in the patient compared to the normal donor control CD4+ T cells stimulated with aAPCs expressing OX40L, but not 4-1BBL, was statistically significant (n<0.05). This suggests that the patient cells did not respond normally to costimulation with these molecules, and instead fully diluted CFSE as in the anti-CD3 control. These findings are consistent with similar observations reported in 4-1BB-deficient CD4 T cells [34]. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules such as OX40 and 4-1BB normally occur after stimulation through the TCR, and may provide check point signals as well as upregulate survival signals to prevent activation-induced cell death.

Figure 3. Polyclonal stimulation of patient CD4 results in enhanced proliferation.

Cryopreserved PBMCs from patient or normal donor control were thawed, labeled with CFSE and co-cultured with CD32 aAPCs alone (no stimulation) or loaded with anti-CD3 that were expressing costimulatory ligands 4-1BBL or OX40L. Proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry and data analyzed using FlowJo software. A. Overlay of histograms representing CFSE dilutions of CD4+ cells on day 6 in the culture. Experiment was conducted in duplicate, and gated on CD4+ T cells. B. Relative CFSE preservation index. MFI of CFSE for each of the cultures on day 6 of stimulation was used to calculate the relative preservation of CFSE expression as described in the materials and methods. Mean values obtained for patient CD4+ T cells (black) stimulated with anti-CD3 loaded K562 aAPCs expressing OX40L or 4-1BBL compared to 8 normal donors (gray). Error bars represent +/- standard deviation. A two-tailed student t-test was performed and p values (* <0.05) were considered statistically significant. Plots are representative of three independent experiments using patient PBMCs and normal donor controls.

Since the patient did not have an obvious lymphoproliferative syndrome, we hypothesized that the increased proliferation would be associated with a consequently increased amount of cell death. To evaluate this we analyzed the cell viability using VIAPROBE or 7-AAD on day 6 in response to costimulation (Figure 4). 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) is a nucleic acid dye, similar to propidium iodide, which is used as a viability probe. Dying cells with compromised membrane integrity will take up the VIAPROBE (7-AAD) dye, and can be detected using flow cytometry [35]. PBMCs from both patient and normal controls cocultured with aAPCs in the absence of anti-CD3 antibody resulted in cell death. While normal donor CD4+ T cells costimulated via OX40L maintained their viability, the viability of patient CD4+ T cells stimulated was reduced. Several experiments using multiple normal donors revealed that this result was statistically significant (n<0.05). Stimulation with aAPC and anti-CD3 without costimulation showed increased survival in control cells, but not in the patient’s, suggesting signaling through inducible endogenous costimulatory molecules was intact in the control cells. Costimulation with aAPCs expressing 4-1BBL rescued patient cells and the differences compared to the normal donor controls were not statistically significant, suggesting that signaling through 4-1BB was intact in the patient consistent with the genomic presence of two copies of this gene. Several costimulatory signals are likely required for achievement of functional T cell responses, and different signals may be required at different times. As OX40 and 4-1BB are inducible signals and play a role to sustain ongoing immunologic responses, a coordinated and sequential process is suggested in mouse models and signaling through 4-1BB may follow OX40 and hypothetically explain the increased proliferation in 4-1BBL [6]. Notably, stimulation with aAPCs expressing OX40L resulted in decreased viability of expanded CD4 T cells from the patient relative to control. The increased activation induced cell death in patient cells suggests a lack of upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes that are normally induced by OX40 (Figure 4). There was no distinct difference in proliferation or survival of patient CD8 T cells compared to normal donor controls (data not shown), supporting the differential role of OX40 in CD4 and CD8 T cells. The anti-apoptotic genes normally upregulated by costimulatory survival signals may affect the proliferation kinetics of the normal donor cells in culture, but their lack of signaling in the patient’s cells resulted in similar kinetics as stimulation with anti-CD3 alone. These results demonstrate a relatively specific insufficiency of OX40 function in the patient’s CD4 T cells. This may have contributed to the patient’s susceptibility to recurrent infections by impairing the survival of new effector cells generated during primary responses, and leading also to lack of efficient T cell help.

Figure 4. Polyclonal stimulation of patient CD4 results in decreased viability.

Cryopreserved PBMCs from patient or normal donor control were thawed and co-cultured with CD32 aAPCs alone (no stimulation) or loaded with anti-CD3 that were expressing costimulatory ligands 4-1BBL or OX40L. Decrease in viability of CD4+ cells from patient compared to healthy donor. Cell viability was measured on day 6 in culture using VIAPROBE (7-AAD). Experiment was conducted in duplicate. Viability was assessed using flow cytometry and analyzed using Flowjo software. Left: Histograms representing VIAPROBE (7-AAD) +/− expression in CD4+ T cells from normal donor control (top) and patient (bottom). Right: Mean percentages of VIAPROBE+ CD4+ T cells for patient (black) were calculated and compared to 8 normal donor controls (gray). Error bars represent +/− standard deviation. A two-tailed student t-test was performed, and those p values (* p < 0.05, ** p< 0.001) were considered statistically significant. Representative of at least three independent experiments.

We described decreased OX40 expression in a patient diagnosed with monosomy 1p36, associated with the inefficient generation of immune responses possibly due to lack of proper T cell help. Haploinsufficiency in the majority of the patient cells likely resulted in the reduced expression of OX40. Immune evaluation revealed an inability to generate recall response to routine vaccine antigens. In addition, our patient had a history of recurrent infections and therefore was treated with IVIG.

Our patient’s presentation parallels mouse models of OX40 deficiency. While studies of OX40 deficient mice have helped to elucidate the role of OX40, heterozygous mice have not been specifically characterized. Many studies using murine models provide evidence that OX40 plays a more important role in generating a secondary response to viral and protein antigens by inducing anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-xl and promoting survival of CD4 T cells upon ligation [12,11,36,24,13,15,37,22,23,38]. Through these signals, OX40 is thought to increase the number of effector cells that can then enter the memory cell pool [11,6,39]. Thus, it is possible that OX40 haploinsufficiency in our patient led to inadequate survival of key memory T cells, consistent with the patient’s inability to respond to recall antigens in vitro.

The expression of other TNFRSF molecules was also reduced in the patient, including 4-1BB and CD30, compared to normal controls following activation and it is unclear at this time why this was observed as she was not haploinsufficient for 4-1BB. TNFRSF expression was only studied for 6 days, thus it is also possible that the induction of the other molecules occurred earlier in the patient’s cells, correlating with the enhanced proliferation kinetics. Despite lower 4-1BB surface expression at day 6, CD4 T cell proliferation was enhanced when patient cells were stimulated through 4-1BB, similar to what has been reported in 4-1BB deficient mice [34]. Increased cell death was only seen after OX40 signaling, thus demonstrating that despite increased 4-1BB induced proliferation, this effect was likely suppressed phenotypically in the patient. Unfortunately, limited patient samples due to her untimely death from sepsis prevented further studies from being conducted.

Many patients with deletions of 1p36 are haploinsuffient for the region containing OX40 [1]. Other patients with deletions in this region may have had unrecognized immunological deficits. Our results suggest that our patient’s immune system was affected by her haploinsufficiency for OX40. Alternatively, her monosomy may have uncovered a novel unidentified mutation in her remaining 1p36 region, leading to an immunologic defect. However, due to the presence of reduced levels of OX40 by FACS in the patient’s cells compared to normal controls, our results demonstrate specific functions for OX40 in vitro. Other patients who have a deletion including this gene may have milder forms of immunologic abnormalities and present an important focus for further evaluation of this syndrome. Because many TNFRSF family members are located in the same region, it may be important to screen other monosomy 1p36 patients for terminal deletions that include these genes and compare their immune status. The close chromosomal location of many TNFRSF family members implies that they may be derived from duplication [32], but studies indicate that they have distinct roles in the immune system and one molecule may not compensate for the loss of another [6,40,41,42]. Deletions can be detected in these patients that vary from 1Mb to greater than 10.5 Mb [42], further supporting the need to investigate whether varying degrees of immunodeficiency occur in patients with this syndrome. Identification of patients with monosomy 1p36 who also have homozygous or heterozygous mutations in these TNFRSFs not only would increase our current understanding of T cell costimulation, but also prompt interventions such as prophylactic antibiotics, immunoglobulin replacement, or perhaps even agonistic antibody treatments if necessary resulting in generally improved clinical outcomes for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the patient’s family who gave permission for the research and for its publication. This work was supported in part by the Jeffrey Modell Center Diagnostic Center at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the Ethel Brown Foerderer Fund, 5R01CA105216 `and P50 HL74731 from the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Heilstedt HA, Ballif BC, Howard LA, Lewis RA, Stal S, Kashork CD, Bacino CA, Shapira SK, Shaffer LG. Physical map of 1p36, placement of breakpoints in monosomy 1p36, and clinical characterization of the syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72:1200–1212. doi: 10.1086/375179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapria SK, McCaskill C, Northrup H, Spikes AS, Elder FFB, Sutton VR, Korenberg JR, Greenberg F, Shaffer LG. Chromosome 1p36 deletions: The clinical phenotype and molecular characterization of a common newly delineated syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;61:642–650. doi: 10.1086/515520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurosawa K, Kawame H, Okamoto N, Ochiai Y, Akatsuka A, Kobayashi M, Shimohira M, Mizuno S, Wada K, Fukushima Y, Kawawaki H, Yamamoto T, Masuno M, Imaizumi K, Kuroki Y. Epilepsy and neurological findings in 11 individuals with 1p36 deletion syndrome. Brain & Development. 2005;27:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gajecka M, Yu W, Ballif BC, Glotzbach CD, Bailey KA, Shaw CA, Kashork CD, Heilstedt HA, Ansel DA, Theisen A, Rice R, Rice DPC, Shaffer LG. Delineation of mechanisms and regions of dosage imbalance in complex rearrangements of 1p36 leads to a putative gene for regulation of cranial suture closure. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;13:139–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann LM, Polster T, Spantzel T, Bartsch O. Unexpected death of a 12 year old boy with monosomy 1p36. Genetic Counseling. 2004;15:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: Keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nature Reviews Immunology. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts TH. Tnf/tnfr family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annual Review of Immunology. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croft M. Costimulation of T cells by OX40, 4-1BB, and CD27. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2003;14:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinberg AD, Evans DE, Thalhofer C, Shi T, Prell RA. The generation of T cell memory: a review describing the molecular and cellular events following OX40 (CD134) engagement. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2004;75:962–972. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song AH, Tang XH, Harms KM, Croft M. OX40 and Bcl-X-L promote the persistence of CD8 T cells to recall tumor-associated antigen. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:3534–3541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salek-Ardakani S, Halteman BS, Akiba H, Yagita H, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) costimulation controls the response of memory T cells. Faseb Journal. 2003;17:C214. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers PR, Song JX, Gramaglia I, Killeen N, Croft M. OX40 promotes Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of CD4 T cells. Immunity. 2001;15:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song JX, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) signals inhibit CD4 T cell apoptosis through multiple effects on the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Faseb Journal. 2002;16:A313. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song JX, Cheng M, Tang XH, Altieri DC, Croft M. OX40 signals regulate Survivin expression and enhance CD4 T cell expansion. Faseb Journal. 2004;18:A810. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung J, Rogers PR, Jember A, Croft M. OX40 upregulates bcl-XL and bcl-2 and promotes survival of CD4 T cells. Faseb Journal. 2001;15:A344. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salek-Ardakani S, Song SX, Halteman BS, Jember AGH, Akiba H, Yagita H, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) controls memory T helper 2 cells that drive lung inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;198:315–324. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaspal FMC, Kim MY, McConnell FM, Raykundalia C, Bekiaris V, Lane PJL. Mice deficient in OX40 and CD30 signals lack memory antibody responses because of deficient CD4 T cell memory. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174:3891–3896. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linton PJ, Bautista B, Biederman E, Bradley ES, Harbertson J, Kondrack RM, Padrick RC, Bradley LM. Costimulation via OX40L expressed by B cells is sufficient to determine the extent of primary CD4 cell expansion and Th2 cytokine secretion in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gramaglia I, Jember A, Pippig SD, Weinberg AD, Killeen N, Croft M. The OX40 costimulatory receptor determines the development of CD4 memory by regulating primary clonal expansion. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:3043–3050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato H, Kojima H, Ishii N, Hase H, Imai Y, Fujibayashi T, Sugamura K, Kobata T. Essential role of OX40L on B cells in persistent alloantibody production following repeated alloimmunizations. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2004;24:237–248. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCI.0000025445.21894.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendriks J, Xiao YL, Rossen JWA, van der Sluijs KF, Sugamura K, Ishii N, Borst J. During viral infection of the respiratory tract, CD27, 4-1BB, and OX40 collectively determine formation of CD8(+) memory T cells and their capacity for secondary expansion. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:1665–1676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers PR, Croft M. Both Ox40 and CD28 are required for long-term Th1/Th2 effector development and T cell survival. Faseb Journal. 2000;14:A985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salek-Ardakani S, Croft M. Regulation of CD4 T cell memory by OX40 (CD134) Vaccine. 2006;24:872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J, Salek-Ardakani S, Rogers PR, Cheng M, Van Parijs L, Croft M. Sustained Akt activation mediated by OX40 controls long-term antigen driven CD4 T cell survival. Faseb Journal. 2003;17:C227. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuber E, Neurath M, Calderhead D, Fell HF, Strober W. Cross-Linking of Ox40 Ligand, A Member of the Tnf/Ngf Cytokine Family Induces Proliferation and Differentiation in Murine Splenic B-Cells. Immunity. 1995;2:507–521. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuber E, Neurath M, Calderhead D, Fell P, Strober W. The Ox40-Ox40l Interaction - A Novel Pathway in T-Cell-Dependent B-Cell Activation. Faseb Journal. 1995 Mar 10;9:A771. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaffer UG, Kashork CD, Saleki R, Rorem E, Sundin K, Ballif BC, Bejani BA. Targeted genomic microarray analysis for identification of chromosome abnormalities in 1500 consecutive-clinical cases. Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;149:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray JW. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1986;83:2934–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suhoski MM, Golovina TN, Aqui NA, Tai VC, Varela-Rohena A, Milone MC, Carroll RG, Riley JL, June CH. Engineering Artificial Antigen-presenting Cells to Express a Diverse Array of Co-stimulatory Molecules. Mol.Ther. 2007 Mar 20; doi: 10.1038/mt.sj.6300134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas AK, Maus MV, Shalaby WS, June CH, Riley JL. A cell-based artificial antigen-presenting cell coated with anti-CD3 and CD28 antibodies enables rapid expansion and long-term growth of CD4 T lymphocytes. Clinical Immunology. 2002;105:259–272. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maus MV, Thomas AK, Leonard DGB, Allman D, Addya K, Schlienger K, Riley JL, June CH. Ex vivo expansion of polyclonal and antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by artificial APCs expressing ligands for the T-cell receptor, CD28 and 4-1BB. Nature Biotechnology. 2002;20:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collette Y, Gilles A, Pontarotti P, Olive D. A co-evolution perspective of the TNFSF and TNFRSF families in the immune system. Trends in Immunology. 2003;24:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Snyder KM, Suhoski MM, Maus MV, Kapoor V, June CH, Mackall CL. 4-1BB is superior to CD28 costimulation for generating CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes for adoptive immunotherapy. J.Immunol. 2007 Oct 1;179:4910–4918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SW, Vella AT, Kwon BS, Croft M. Enhanced CD4 T cell responsiveness in the absence of 4-1BB. Journal of Immunology. 2005 Jun 1;174:6803–6808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid I, Krall WJ, Uittenbogaart CH, Braun J, Giorgi JV. Dead cell discrimination with 7-amino-actinomycin D in combination with dual color immunofluorescence in single laser flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1992;13:204–208. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphreys IR, Schneider K, Benedict C, Munks M, Hill A, Ware C, Croft M. OX40 mediates CD8 T cell responses to persistent murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection. Faseb Journal. 2005;19:A397. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg AD, Vella AT, Croft M. OX-40: life beyond the effector T cell stage. Seminars in Immunology. 1998;10:471–480. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SW, Park Y, Cheroutre H, Kwon BS, Croft M. Functional dichotomy between OX40 and 4-IBB in modulating effector CD8 T cell responses. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:S182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huddleston CA, Weinberg AD, Parker DC. OX40 (CD134) engagement drives differentiation of CD4(+) T cells to effector cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2006;36:1093–1103. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Florido M, Borges M, Yagita H, Appelberg R. Contribution of CD30/CD153 but not of CD27/CD70, CD134/OX40L, or CD137/4-1BBL to the optimal induction of protective immunity to Mycobacterium avium. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2004;76:1039–1046. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agostini M, Cenci E, Pericolini E, Nocentini G, Bistoni G, Vecchiarelli A, Riccardi C. The glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related gene modulates the response to Candida albicans infection. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:7502–7508. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7502-7508.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballif BC, Yu W, Shaw CA, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG. Monosomy 1p36 breakpoint junctions suggest pre-meiotic breakage-fusion-bridge cycles are involved in generating terminal deletions. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:2153–2165. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]