Abstract

Bcl10 and MALT1 are essential mediators of NF-κB activation in response to the triggering of a diverse array of transmembrane receptors, including antigen receptors. Additionally, both proteins are translocation targets in MALT lymphoma. Thus, a detailed understanding of the interaction between these mediators is of considerable biological importance. Previous studies have indicated that a 13-amino acid region downstream of the Bcl10 caspase recruitment domain (CARD) is responsible for interacting with the immunoglobulin-like domains of MALT1. We now provide evidence that the death domain of MALT1 and the CARD of Bcl10 also contribute to Bcl10-MALT1 interactions. Although a direct interaction between the MALT1 death domain and Bcl10 cannot be detected via immunoprecipitation, FRET data strongly suggest that the death domain of MALT1 contributes significantly to the association between Bcl10 and MALT1 in T cells in vivo. Furthermore, analysis of point mutants of conserved residues of Bcl10 shows that the Bcl10 CARD is essential for interaction with the MALT1 N terminus. Mutations that disrupt proper folding of the Bcl10 CARD strongly impair Bcl10-MALT1 interactions. Molecular modeling and functional analyses of Bcl10 point mutants suggest that residues Asp80 and Glu84 of helix 5 of the Bcl10 CARD directly contact MALT1. Together, these data demonstrate that the association between Bcl10 and MALT1 involves a complex interaction between multiple protein domains. Moreover, the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction is the second reported example of interactions between a CARD and a non-CARD protein region, which suggests that many signaling cascades may utilize CARD interactions with non-CARD domains.

Bcl10 and mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue 1 (MALT1)5 are cytosolic signaling intermediates in the pathway connecting antigen receptors to activation of the NF-κB transcription factor (1, 2). Targeted mutation of the gene encoding either protein results in severe impairment of T cell and B cell proliferative responses to antigen stimulation, due to the failure to activate NF-κB (3–6). Additionally, cytogenetic studies have revealed that both MALT1 and Bcl10 are recurrent translocation targets in a subclass of B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT) lymphoma (7, 8). Thus, Bcl10 and MALT1 are essential for adaptive immune responses and are likely to play a significant role in the etiology and/or pathogenesis of MALT lymphoma.

The antigen receptor to NF-κB signaling pathway involves a cascade of protein-protein interactions and protein modifications that ultimately result in phosphorylation and degradation of the inhibitory binding partner of NF-κB, called IκB. This degradation event allows translocation of the heterodimeric NF-κB transcription factor from the cytosol to the nucleus (9). Although some of the signaling intermediates utilized in this pathway, such as the trimeric IκB kinase (IKK) complex, are common to NF-κB signaling cascades that are coupled to other cellular receptors (e.g. Toll-like receptors of the innate immune system), the portion of the cascade upstream of the IKK complex is limited to specific ligand-triggered pathways, including the antigen receptor-directed NF-κB activation cascade (1, 2).

In T cells, the T cell receptor (TCR) transmits an activating signal to PKCθ (10). PKCθ then phosphorylates specific target residues within the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) protein, CARMA1 (11). This phosphorylation promotes the assembly of a trimeric complex of CARMA1, Bcl10, and MALT1 (12) and the concomitant oligomerization of the Bcl10-MALT1 complex (13, 14). Oligomerized MALT1, in conjunction with the ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 and the ubiquitin conjugating enzymes UBC13 and MMS2, adds Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains to NEMO/IKKγ, leading to the phosphorylation and activation of IKKβ by the kinase TAK1 (15). Activated IKKβ then phosphorylates IκBα, triggering the terminal portion of the NF-κB activation cascade. Caspase 8 also participates in transducing the signal from Bcl10 and MALT1 to the IKK complex, through stabilizing the interaction between Bcl10/MALT1 and the IKK complex and through recruitment of Bcl10/MALT1 to lipid rafts (16, 17).

In lymphocytes, the N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD) of Bcl10 binds to the CARD of CARMA1, and this interaction is required for transduction of the NF-κB activating signal (18–22). A similar or identical CARMA1-Bcl10-MALT1-mediated pathway appears to connect ITAM-coupled NK cell receptors to NF-κB activation (23, 24). In myeloid cells, recent studies have shown that CARD9 functions as a surrogate for CARMA1 in connecting the dectin-1 receptor, CD16, TREM, and other ITAM-coupled myeloid receptors to Bcl10/MALT1 (25, 26). Similarly, in non-immune system cells, certain G protein-coupled receptors are coupled to Bcl10/MALT1 via CARMA3 (27, 28). Thus, many receptors are coupled to the Bcl10/MALT NF-κB activation module via an upstream activator that contacts Bcl10 via a CARD-CARD interaction.

Recently, MALT1 has also been shown to mediate additional functions related to T cell activation, cleaving both the ubiquitin editing enzyme, A20, and the C terminus of Bcl10. These activities are dependent both on a functional MALT1 caspase-like domain and on TCR signals transmitted through CARMA1 and Bcl10. Evidence suggests that MALT1-mediated cleavage of A20, a negative modulator of NF-κB activation, further potentiates TCR-stimulated NF-κB activation (29). In contrast, data suggest that MALT1 cleavage of the Bcl10 C terminus is not important for NF-κB activation, but rather facilitates β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin, perhaps via modification of integrin contacts with the cytoskeleton (30).

The currently accepted model of Bcl10-MALT1 interaction is that the immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains of MALT1 directly bind to Bcl10 through a 13-amino acid (aa) motif that is immediately downstream of the Bcl10 CARD. Deletion of this 13-aa domain disrupts the ability of Bcl10 both to activate NF-κB and to associate with MALT1 in immunoprecipitation assays (31). Due to the critical nature of the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction in numerous pathways of NF-κB activation, we performed mutagenesis studies to further define the requirements for Bcl10 physical and functional interactions with MALT1. Deletion mutants of MALT1 analyzed by FRET strongly suggest that, in addition to the Ig-like domains, the death domain (DD) of MALT1 contributes significantly to the association between Bcl10 and MALT1 in vivo. Furthermore, site-directed mutagenesis of the Bcl10 protein demonstrates that the region of Bcl10 that interacts with MALT1 is larger than previously reported, extending into the Bcl10 CARD. Thus, the MALT1 DD and Ig-like domains associate with the Bcl10 CARD and 13-aa MALT1 binding motif to stabilize the Bcl10-MALT1 complex. These results provide previously unknown molecular details concerning the interaction between Bcl10 and MALT1, and indicate that the physical interaction of these molecules is more complex than previously appreciated. Additionally, the Bcl10-MALT1 complex represents the second reported example of interactions between a CARD and a non-CARD protein region (32), suggesting that such CARD-non-CARD interactions may occur in many signaling pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Transfections, and Luciferase Assays—D10 T cells and CH12 B cells were maintained as previously described (14). HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfections were performed by a modified calcium phosphate method (33). For luciferase assays, 1.2 × 105 HEK293T cells were plated per well in a 24-well plate. NF-κB activation was assessed as previously described by Lucas et al. (31) with 112.5 ng of Bcl10-GFP mutant plasmid (cloned in the pENeo vector), 4.5 ng of the NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter pBVI-NF-κB-Luc, 49.5 ng of the β-galactosidase reporter pEF1-Bos-βgal (an internal control), 45 ng of pcDNA-p35 (to promote cell survival), and 388.5 ng of the carrier plasmid, pBS-KS+, for a total of 600 ng. Luciferase assays were performed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Mountain View, CA) at 48 h post-transfection, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. β-Galactosidase assays were performed using the β-Galactosidase Reporter Gene Activity Detection Kit (Sigma). Luciferase values for each sample were normalized to the corresponding β-galactosidase values, and reported as –fold induction relative to control cells transfected with reporter vectors only.

Mutagenesis and Retroviral Infections—Clustal W alignments (34) were performed using the worldwide web server at the European Bioinformatics Institute. Deletion and point mutants of the Bcl10-GFP fusion protein were produced via PCR mutagenesis, using standard methodology. N-terminal FLAG- and C-terminal YFP-tagged deletions of the murine MALT1 cDNA were constructed as previously described (13). MALT1-DD-only contains MALT1 residues 2–131; MALT1–2xIg-only contains residues 132–327; the MALT1-ΔIg construct contains a deletion of residues 132–344; and the MALT1-ΔDD construct contains a deletion of residues 1–131. Other MALT1 deletions and the Bcl10-CFP construct were previously described (13). Myc-tagged CARMA1 cDNA was a gift from J. Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University) and D. Baltimore (Caltech). The above constructs were cloned into the retroviral expression vectors, pENeo or pEhyg (35). Retroviral infection and selection of D10 T cells were as previously described (14).

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting—HA-Bcl10-GFP constructs were produced by cloning three repeats of the HA epitope tag immediately upstream of the Bcl10 open reading frame, and these gene fusions were cloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). FLAG-MALT1 deletion mutants and FLAG-CARMA1 were cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector. For each sample, 1.2 × 106 HEK293T cells were distributed between two wells of a 6-well plate. Following overnight growth, cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method, using 1.5 μg of pcDNA3–3xHA-Bcl10-GFP and 1.5 μg of pcDNA3-FLAG-construct (MALT1 deletion or CARMA1) per well. After 48 h, cells from the two wells were harvested and pooled; 1/6 of the cells were used for whole cell lysates (direct lysis and sonication in 1× Laemmli buffer). The remaining 5/6 of the cells were incubated in IP lysis buffer (20 mm Tris pH 7.5, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.25 m NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, 3 mm EGTA, 50 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, 50 μm leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 30 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C (14,000 × g) for 10 min. Supernatants were pre-cleared with 10 μl of Protein -G-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) at 4 °C with rotation for 1 h, and then immunoprecipitated for 16 h with 2 μg of mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (M2) (Sigma) at 4 °C with rotation. Immunoprecipitates were captured with 20 μl of Protein-G-Sepharose (1 h, 4 °C), and washed 3 times in 1 ml of IP lysis buffer. The samples were then boiled in 1× Laemmli buffer. The denatured immunoprecipitated proteins from ∼4 × 105 cell eq were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. HA-Bcl10-GFP was detected by Western blotting, using a rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (Y-11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Whole cell lysates were probed with rabbit anti-HA or rabbit anti-FLAG to detect HA-Bcl10 or FLAG-MALT1/-CARMA1, respectively.

Three-dimensional Modeling—The model for the CARD and minimal MALT1 binding region of murine Bcl10 (aa 13–119 of NCBI sequence AAH24379) was built using the three-dimensional structure of the CARD of RAIDD (Protein Data Bank ID 3CRD). 3CRD was selected at the template using PSI-BLAST (36) and PDB-BLAST on the basis of E value, which describes the likelihood that a sequence with a similar score will occur in the data base by chance. The query sequence was submitted to the 3DPSSM server (37), which detects the protein folds against a data base of fold libraries from known protein structures independent of their sequence similarity with query sequence. 3DPSSM alignment results were used to align target and template sequences. The model was built using two different servers, SwissPDB Viewer (SPDBV) (38) and Modeler 8v2 (39). The alignment was constructed manually by loading the template and target sequences into the SPDBV alignment tool. The structurally corrected alignment was used to construct a theoretical three-dimensional model of the target in the SPDBV server and Modeler. These restraints were expressed as probability density functions, and the model with the smallest probability function was selected for further refinements. The stereochemical quality of the models was assessed by using PROCHECK (40). Verify three-dimensional server (41) was used to test the accuracy of the models using three-dimensional-one-dimensional profile score. We selected the model generated by Modeler, because most of the residues fall in the favored regions of the main Ramachandran plot (42) in PROCHECK, and the three-dimensional-one-dimensional graph was found to be satisfactory.

Microscopy and FRET Analysis—D10 T cells stably expressing Bcl10-GFP constructs were conjugated with conalbumin-primed CH12 B cells for 20 min at 37 °C, as previously described (14). Acquisition of images employed an Axiovert 200M microscope and ×63 plan-apochromat oil objective (Carl Zeiss Inc., Germany), connected to a TILL-Photonics epifluorescence imaging system for POLKADOTS analysis, or a Pascal confocal system (Carl Zeiss Inc., Germany) using a ×40 plan-apochromat oil objective (FRET analyses). Epifluorescence images were acquired as 15 μm z-stacks in steps of 0.3 μm, and image data were digitally deconvolved using a constrained-iterative algorithm (TILLvisION, TILL Photonics, Germany). Identification of cells with POLKADOTS and FRET calculations were performed as previously described (13).

FRET Analysis by FACS—D10 T cells were infected with retroviral vectors and drug selected to produce stable cell lines, as described above. All FRET constructs employed the cerulean variant of CFP (43) and citrine variant of YFP (44), each with the A206K mutation (45) to prevent fluorescent protein dimerization. Negative controls for FRET consisted of cells expressing CFP alone, YFP alone, MALT1-ΔC-CFP alone, Bcl10-WT-YFP alone, and co-expressed CFP+YFP (unlinked). A fused CFP-YFP construct, joined by the linker GGAGSIDGSGRELGR, was used as a FRET positive control, and this construct was nucleoporated into D10 T cells to avoid reverse transcription-mediated recombination between the fluorescent proteins (46). Flow cytometry FRET analysis was performed as described (47, 48), with the following exceptions. The 405 and 488 laser lines of a BD Biosciences LSRII were used to excite CFP and YFP, respectively. A 450/50 filter was used for CFP detection and a 585/42 filter was used for detection of the YFP and FRET signals. Compensations in the range of 1.0–1.2 and 80–90% were used for FRET-YFP and FRET-CFP, respectively. For creation of the FRET channel histograms, cells co-expressing MALT1-ΔC and Bcl10-YFP constructs were gated on the live cell population (defined by forward and side scatter parameters) and on a population defined by the upper and lower limits of YFP fluorescence for Bcl10-WT. Each control cell line was gated on live cells and the major fluorescent population.

FRET Analysis by FLIM—D10 T cell lines were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, and fluorescence lifetime images were collected with a LIFA frequency domain FLIM system (Lambert Instruments, The Netherlands) attached to an Olympus IX71 epifluorescence microscope, employing a ×60 1.45 NA objective. Illumination was provided by a 443-nm modulated LED, and 12-phase step images (40 MHz frequency) were acquired with a modulated ICCD (intensified charge-coupled device) camera. Donor emission images were collected through a CFP filter. For each cell line, the fluorescent lifetimes of 20–70 cells were measured and averaged. Lifetime values were used to calculate FRET efficiencies employing the calculation tool in LI-FLIM software (version 1.2.2; Lambert Instruments, The Netherlands). For statistical analyses, p values were calculated by paired t-tests comparing FRET efficiencies from cell lines expressing each Bcl10 mutant versus the cell line expressing Bcl10-WT.

RESULTS

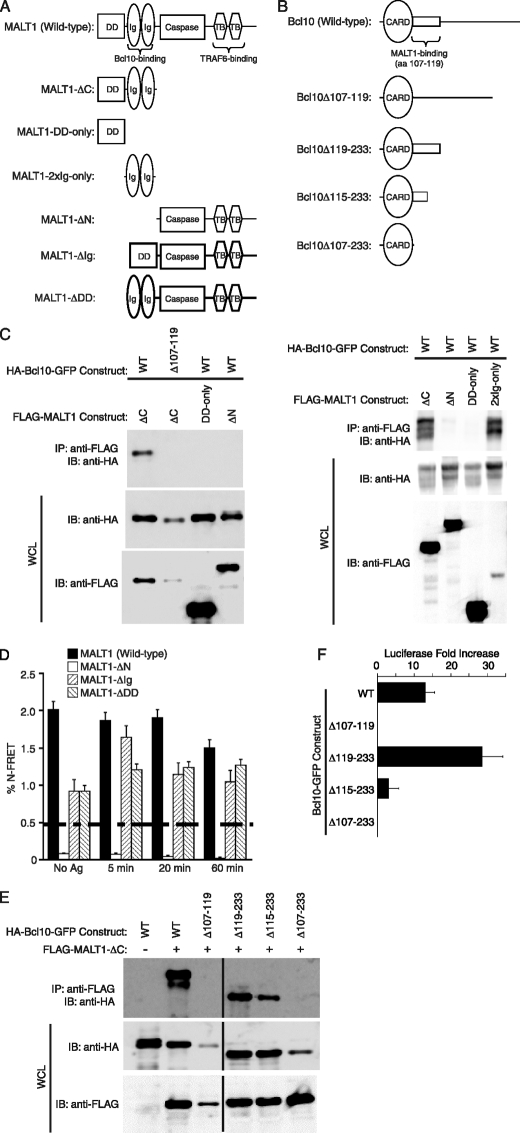

DD and the Ig-like Domains of MALT1 Contribute to the in vivo Association between Bcl10 and MALT1—Previous reports (31, 49) have shown that Bcl10 and MALT1 directly interact, and that this interaction is required for Bcl10-mediated activation of NF-κB. The data of Lucas et al. (31) demonstrated that this interaction depends on a short peptide domain immediately downstream of the Bcl10 CARD, consisting of aa 107–119 of Bcl10. To confirm and extend these previous studies, we made several deletion mutants of MALT1 and Bcl10 (Fig. 1, A and B). Various combinations of these mutants were co-transfected into HEK293T cells, and immunoprecipitation (IP) analyses were performed, using anti-FLAG to immunoprecipitate the MALT1 constructs (Fig. 1C). Consistent with previous studies (31, 49), Fig. 1C shows that only MALT1 constructs that contain the Ig-like domains (MALT1-ΔC and MALT1–2xIg-only) are capable of interacting with wild-type Bcl10 in this IP assay. The other two MALT1 fragments (MALT1-ΔN and MALT1-DD-only), which lack the Ig-like domains, are unable to interact with Bcl10. Similarly, a Bcl10 mutant (Bcl10Δ107–119) that lacks the previously defined minimal MALT1 interaction motif (31) is unable to interact with the Ig-like domains of the MALT1-ΔC construct.

FIGURE 1.

Deletional analysis defines the MALT1 Ig-like domains, the DD, and Bcl10 residues 1–114 as critical determinants of Bcl10-MALT1 interaction. A, diagram of the domains of full-length MALT1 and the MALT1 deletion mutants used in this study. For simplicity, the N-terminal FLAG and C-terminal YFP tags are not shown. B, diagram of the domains of full-length Bcl10 and the Bcl10 deletion mutants used in this study. For simplicity, the N-terminal HA and C-terminal GFP tags are not shown. C, co-IP analyses of interactions between Bcl10 (wild-type or Δ107–119) and the MALT1 deletion constructs shown in A. MALT1 and Bcl10 expression vectors were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. IP of MALT1 was performed with an anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Western blotting with an anti-HA antibody to detect co-immunoprecipitated Bcl10. Whole cell lysates were also probed with anti-HA and anti-FLAG to evaluate expression of the Bcl10 and MALT1 constructs. Note that co-transfections of Bcl10Δ107–119 and MALT1-ΔC consistently resulted in reduced levels of expression of Bcl10Δ107–119, in comparison to co-transfections with other Bcl10 deletion mutants. D, FRET analysis of interactions between Bcl10-CFP and the MALT1-YFP constructs shown in A, in the absence of specific antigen stimulation and at several time points post-stimulation with conalbumin-loaded CH12 B cells. FRET was performed as previously described (13). The dashed line indicates the threshold for significant FRET detection in this study. E, co-IP analyses of interactions between MALT1-ΔC and the Bcl10 constructs depicted in B. IPs and Western blots were performed as in C. F, luciferase assays in HEK293T cells measuring the ability of the indicated Bcl10 constructs to drive activation of an NF-κB reporter construct. Luciferase activity is expressed as –fold increase relative to NF-κB reporter alone, which is defined as 1.0. Error bars are S.E. Note that Δ107–119 and Δ107–233 had lower levels of luciferase activation than NF-κB reporter alone in this experiment. Caspase, caspase-like domain; TB, TRAF6-binding domain; WT, wild-type; IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting.

To assess the requirements for in vivo interactions between Bcl10 and MALT1 in T cells, we performed FRET analysis, measuring the association between wild-type Bcl10-CFP and four different MALT1-YFP constructs (Fig. 1D). Retroviral expression vectors were used to stably express the MALT1-YFP and Bcl10-CFP constructs in D10 T cells, as previously described (14). Unexpectedly, we observed that MALT1 constructs with deletions of either the DD (MALT1-ΔDD) or the two Ig-like domains (MALT1-ΔIg) retain the ability to associate with Bcl10, albeit not to wild-type levels, and not with the same kinetic response to TCR stimulation as observed with the cells expressing wild-type MALT1. Thus, although association between the MALT1 DD and Bcl10 cannot be measured by IP of proteins overexpressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1C and Ref. 31), FRET measurements strongly suggest that the MALT1 DD directly or indirectly contributes to stabilizing the MALT1-Bcl10 interaction in vivo. Consistent with previous results (31, 49), deletion of both the DD and the two Ig-like domains (MALT1-ΔN) completely abolishes association with Bcl10. These FRET measurements thus suggest that both the DD and the two Ig-like domains of MALT1 contribute significantly to the in vivo association between Bcl10 and MALT1 in T cells.

Bcl10 Amino Acids 115–119 Are Not Required for Binding to MALT1 or for NF-κB Activation—To more precisely define the regions of Bcl10 that are required for interaction with MALT1, we examined the ability of Bcl10 C-terminal deletion constructs to interact with MALT1-ΔC. Consistent with previously reported data (31), we observed that Bcl10 residues downstream of aa 118 (Bcl10Δ119–233) are not required for interaction with MALT1 (Fig. 1E). Additionally, a Bcl10 construct that includes only the Bcl10 CARD (Bcl10Δ107–233) is incapable of interaction with MALT1. However, we also made an intermediate deletion, resulting in truncation of Bcl10 within the previously defined minimal MALT1 interaction motif (Bcl10Δ115–233), and we found that this mutant also retains the ability to interact with MALT1, albeit with reduced efficiency. To analyze the NF-κB activation potential of the above mutants, we performed transient transfection of HEK293T cells, using an NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter (Fig. 1F). Relative to wild-type Bcl10, the Bcl10Δ119–233 mutant showed hyper-activation of NF-κB, and Bcl10Δ107–233 had no ability to activate NF-κB. Consistent with IP data (Fig. 1E), Bcl10Δ115–233 was able to activate NF-κB with about 30% efficiency, relative to WT Bcl10. Thus, Bcl10 aa 115–119 are neither required for interaction with MALT1 nor for activation of NF-κB. However, these residues do appear to help stabilize Bcl10 interaction with MALT1, enhancing the ability to activate NF-κB. The C-terminal region of Bcl10 (aa 119–233) does not influence the ability to interact with MALT1, but its presence does lead to a modest inhibition of NF-κB activation. Overall, these data demonstrate that Bcl10 aa 1–114 are sufficient to mediate NF-κB activation and to associate with MALT1.

Molecular Modeling and Mutagenesis of Conserved Residues in a Putative Extended MALT1 Binding Site—Because the Bcl10 CARD comprises the majority of the aa 1–114 fragment required for interaction with MALT1 (Fig. 1E), we hypothesized that the CARD contributes to binding with MALT1. Indeed, in the previous study defining the minimal MALT1 binding site (31), deletional analysis was performed only from the C-terminal end. Thus, the N-terminal boundary of the minimal MALT1 binding site has not been defined. Previous x-ray crystallography analyses suggest that CARD-CARD interactions occur via interaction between the 2–3 helical face, and the 1–4 helical face (50). We therefore focused our attention on the putative 5–6 helical face, which does not yet have a known role in the biology of CARD proteins. Additionally, helix 6 is contiguous with the previously defined minimal MALT1 binding site (aa 107–119), further suggesting the helix 5–6 region as a potential site of MALT1 interaction. Although most data indicate that CARDs interact with other CARDs, a recent report has described an interaction between a CARD and a non-CARD protein (32).

To further define the molecular determinants for Bcl10 association with MALT1 and Bcl10-driven NF-κB activation, we created numerous point mutations in the helix 5–6 region (aa 79–104; Fig. 2A) and in Bcl10 aa 105–119 (Fig. 2B), which includes the previously defined minimal MALT1 binding site (31). To guide the mutagenesis strategy, we performed Clustal W alignment of Bcl10 proteins from various species. Although mammalian Bcl10 clones (mouse, human, and rat) are nearly identical, Bcl10 from more distantly related vertebrates, birds (chicken) and fish (fugu), are more highly divergent in this region.

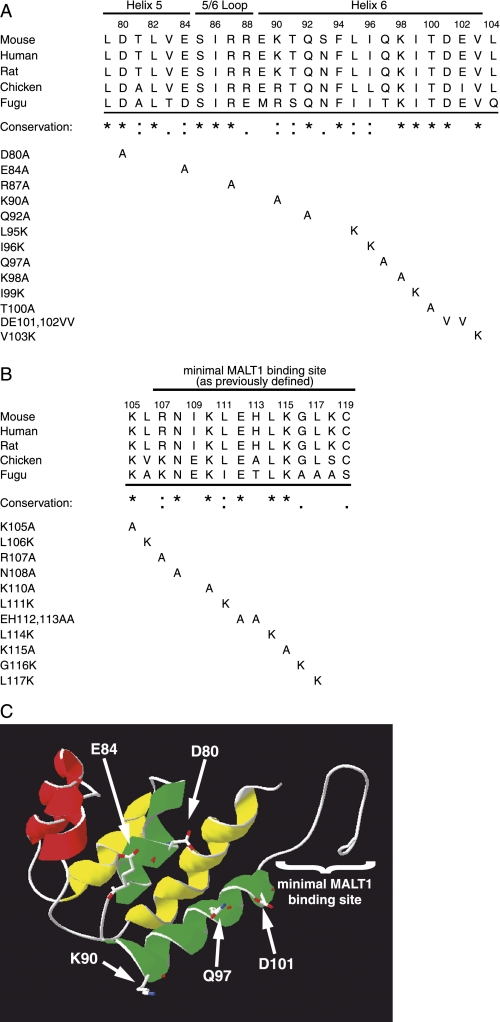

FIGURE 2.

Identification of conserved residues and structural modeling of the Bcl10 CARD and MALT1-binding region. A, Clustal W alignment of orthologous regions of Bcl10 from various mammals (mouse, human, and rat), birds (chicken), and fish (fugu) from amino acids 79–104 of the mouse sequence. An asterisk (*) indicates amino acid identity for all species, a colon (:) indicates conserved substitutions, and a period (.) indicates semi-conserved substitutions. Single and combinatorial point mutations analyzed in this study are shown below the alignment. The locations of CARD helices 5 and 6 and the connecting 5/6 loop, as determined by molecular modeling (see part C) are indicated above the alignment. B, Clustal W alignment of Bcl10 amino acids 105–119 was performed as described in A. The previously defined minimal MALT1 binding site (31) is indicated by a bar above the alignment. C, a three-dimensional model of Bcl10 amino acids 13–119 was generated using Swiss PDB Viewer, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The six α-helices of the CARD are shown to the left, and the minimal MALT1 binding site (which was modeled as coil) is shown to the right. The helix 1–4 face is indicated by yellow, the helix 2–3 face is in red, and the helix 5–6 face is in green. The model is oriented so that the helix 5–6 face is closest to the viewer, with the 2–3 and 1–4 faces projecting behind. The predicted positions of side chains of five charged or polar residues that were modeled as solvent-exposed amino acids on the helix 5–6 face have been superimposed on the model.

As an additional tool to direct the mutagenesis strategy, we used computational methods to construct a three-dimensional model of the Bcl10 CARD. Fig. 2C shows the results of the best fit model of Bcl10 residues 13–119, which includes both the CARD and the residues required for MALT1 binding. The CARD from RAIDD was used as the template for modeling of the Bcl10 CARD, based on statistical analysis of the homology between these sequences (see “Experimental Procedures” for complete methodology). In this model, helices 1 and 4, 2 and 3, and 5 and 6 are colored yellow, red, and green, respectively. Residues downstream of aa 103 were modeled as coil, and are shown to the right of helix 6. Structural analyses have indicated a prominent role for charged residues in CARD-CARD interactions (50, 51), suggesting that charged residues may also be important for CARD interactions with non-CARD binding partners. We thus determined the location of charged (Asp80, Glu84, Lys90, and Asp101) or polar (Gln97) residues that are predicted to be solvent exposed. These residues are topologically on the helix 5–6 face of the modeled CARD, as shown in Fig. 2C.

Clustal W analysis of the Bcl10 helix 5–6 region showed that there is complete identity at 13/26 residues, conservation at 6/26 residues, and partial conservation at 3/26 residues (Fig. 2A). With the exception of Gln97, the modeled solvent exposed charged/polar residues on the helix 5–6 face were either identical in the analyzed species (Asp80 and Asp101) or conserved (Glu84 and Lys90), further suggesting functional importance. We then produced single point mutants throughout this region, which included all of the modeled solvent-exposed charged/polar residues on the helix 5–6 face and many additional residues, which were identical or conserved across species. We considered analysis of these additional residues important, because it is very likely that aspects of our three-dimensional model of Bcl10 do not accurately represent the actual structure of the CARD. We substituted hydrophobic amino acids with lysine, and all other amino acids with alanine. We also utilized a previously constructed double mutant D101V/E102V, because this mutation included the conserved and modeled solvent-exposed Asp101 residue (as well as the non-conserved Glu102).

Clustal W alignment of Bcl10 aa 105–119 revealed that aa 116–119 are minimally conserved, which is consistent with the deletional analysis in Fig. 1, E and F. Bcl10 aa 107–115 are more highly conserved, with 5/9 identities and 2/9 conserved substitutions (Fig. 2B). We thus made point mutants of all of the conserved residues and two poorly conserved residues (116 and 117) in this region. All residues were substituted with alanines, except for hydrophobic residues, which were mutated to lysines. Among these mutants was the previously generated E112A/H113A double point mutant. However, non-conserved residue 113 is an alanine in chicken, so this mutant effectively represents a single point mutant (E112A). Bcl10 aa 105 and 106 are upstream of the previously defined minimal MALT1 interaction motif (aa 107–119) (31), but downstream of the Bcl10 CARD. The completely conserved Lys105 was mutated to alanine. Although Leu106 is not considered conserved on the basis of Clustal W analysis (Fig. 2A), we noted that all analyzed species contain a hydrophobic residue in this position, and Leu106 was thus substituted with lysine.

In summary, we used multiple-species alignment and molecular modeling to facilitate the design of 24 novel point mutants in the Bcl10 aa 79–119 interval, which includes both the previously defined MALT1 binding site and the predicted helices 5 and 6 of the Bcl10 CARD. These mutations were designed to identify putative amino acid contacts for interaction with MALT1, and to test the hypothesis that conserved amino acids upstream of Bcl10 aa 107 contribute to MALT1 binding.

Effects of Point Mutations in the Helix 5–6 Region of the CARD on Bcl10-mediated NF-κB Activation—To assess the ability of each of the Bcl10 point mutants to activate NF-κB, we performed an NF-κB-luciferase assay (Fig. 3, Table 1), based on overexpression of Bcl10 mutants in HEK293T cells (31). Notably, all of the point mutations involving hydrophobic residues within the helix 5–6 region (L95K, I96K, I99K, and V103K) reduced NF-κB activation to a level indistinguishable from the negative controls, Δ107–119 and G78R (G78R is a mutant that impairs proper folding of the CARD (52)). These results are not surprising, as each of these hydrophobic residues appears to form contacts with residues in other helices (generally also hydrophobic), particularly helix 1 (data not shown). It is thus likely that mutation of each of these hydrophobic residues abrogates NF-κB activation based on destabilization the Bcl10 CARD, rather than by simply affecting the ability of Bcl10 to associate with MALT1.

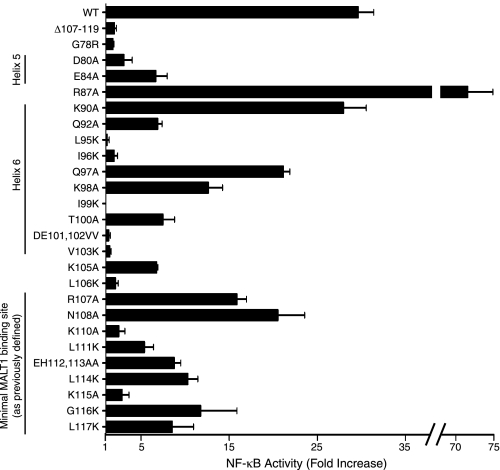

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of NF-κB activation by Bcl10 point mutants. Luciferase assays of NF-κB activation by wild-type (WT) Bcl10 and each of the point mutants from Fig. 2 were performed as described in Fig. 1F. Error bars are S.E. Data are also tabulated in Table 1 as mean percent activation, relative to wild-type.

TABLE 1.

Properties of Bcl10-GFP mutants

| Bcl10-GFP construct | NF-κB activationa | POLKADOTS formationb | MALT1 IPc | CARMA1 IP | Expression in HEK293d | FRET efficiencye | Mutant classf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ++++ | Y | S | S | WTE | WTF | NA |

| Δ107-119 | - | N | - | S | REM | RF | 2 |

| G78R | - | N | W | W | RE | RF | 1 |

| D80A | + | Ng | W | S | WTE | RF | 2 |

| E84A | + | Y | Sh | S | WTE | WTF | 3h |

| R87A | ++++ | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| K90A | ++++ | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| Q92A | + | Ng | W | W | WTE | ND | 1 |

| L95K | - | N | W | W | RE | ND | 1 |

| I96K | - | N | - | W | RE | ND | 1 |

| Q97A | +++ | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| K98A | ++ | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| I99K | - | N | - | W | RE | ND | 1 |

| T100A | ++ | Y | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| D101V/E102V | - | N | - | W | RE | ND | 1 |

| V103K | - | N | - | W | RE | ND | 1 |

| K105A | + | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| L106K | + | Ng | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| R107A | +++ | Y | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| N108A | +++ | Y | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| K110A | + | Y | W | S | WTE | WTF | 2 |

| L111K | + | Y | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| E112A/H113A | ++ | Y | S | S | WTE | WTF | 3 |

| L114K | ++ | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| K115A | + | Y | S | S | WTE | ND | 3 |

| G116K | ++ | Y | W | S | WTE | ND | 2 |

| L117K | ++ | Y | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

++++, >75% WT activation; +++, 50-75% WT activation; ++, 25-50% WT activation; +, 7-25% WT activation; -, <7% WT activation.

Y, yes; N, no.

S, strong IP; W, weak IP; -, no IP; ND, no data.

WTE, near wild-type levels of expression; RE, reduced expression; REM, reduced expression only with MALT1 co-expression.

WTF, wild-type or greater FRET efficiency; RF, reduced FRET relative to WT.

NA, not applicable; 1, destabilized/misfolded CARD; poor binding to MALT1 and CARMA1; 2, diminished affinity for MALT1, wild-type affinity for CARMA1; 3, near wild-type or wild-type affinity for MALT1 and CARMA1.

Indicates a minority population of cells with POLKADOTS that are smaller and less intense than WT.

Indicates IP of MALT1 was weaker than WT in titration experiments.

Among the predicted solvent-exposed charged/polar residues in the Bcl10 helix 5–6 region, mutation of Asp80, Glu84, and D101V,E102V resulted in reduction of NF-κB activation to <25% of wild-type levels (Fig. 3, Table 1), whereas the K90A and Q97A mutants had no effect or only slightly reduced NF-κB activation, respectively. As Gln97 is not conserved, it is not surprising that this mutation had little effect. To more accurately define the contribution of Asp101, we made an additional mutant, D101A. Testing of the D101A mutant showed no reduction of NF-κB activation relative to wild-type (data not shown), perhaps suggesting that the D101V,E102V mutation disrupts proper folding of the CARD by replacing two adjacent hydrophilic residues with hydrophobic amino acids.

The mutants, Q92A, K98A, and T100A exhibited at least a 50% reduction in NF-κB activation (Fig. 3, Table 1). Based on molecular modeling, Gln92 is predicted to be on the underside of helix 6 and to make intra-helical contacts (Fig. 2C and data not shown), and therefore the Q92A mutation may also destabilize the Bcl10 CARD. Lys98 and Thr100 are predicted to be partially solvent exposed, and thus may also represent potential contact residues for MALT1. A final mutant, R87A, increased NF-κB activation. Although Arg87 is predicted to be solvent-exposed in the helix 5–6 connecting loop (Fig. 2C and data not shown), the NF-κB activation data suggest that this residue is unlikely to participate in binding to MALT1.

Overall, mutagenesis of residues within the predicted helix 5–6 region of Bcl10 demonstrated that mutation of the conserved residues Asp80 and Glu84 substantially reduced Bcl10-mediated NF-κB activation. The predicted solvent exposure of these charged residues suggests that Asp80 and Glu84 are good candidate residues for mediating direct contact with MALT1. Furthermore, numerous additional amino acids within the helix 5–6 region of the Bcl10 CARD abrogate or substantially impair Bcl10-mediated activation of NF-κB. As most of these additional residues are predicted to form inter-helical contacts in the Bcl10 CARD, it is likely that the majority of these other weakly activating mutants have an improperly folded CARD.

Effects of Point Mutations in the 105–117 Amino Acid Region on Bcl10-mediated NF-κB Activation—Interestingly, no single point mutation in the region of 105–117 completely abolished NF-κB activation by Bcl10, although mutation of five residues in this region (Lys105, Leu106, Lys110, Leu111, and Lys115) reduced NF-κB activation to 7–25% of wild-type levels (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The Bcl10 mutants E112A/H113A, L114K, G116K, and L117K also reduced NF-κB activation by 25–50%. Overall, these data show that there are numerous conserved residues in the aa 105–117 interval that contribute to the ability of Bcl10 to activate NF-κB. These observations may suggest that there are multiple important Bcl10 contacts for MALT1 binding in this region, and/or that mutations in this region disrupt a conformationally sensitive epitope required for MALT1 binding.

Formation of Bcl10 POLKADOTS Strongly Correlates with the Ability of Bcl10 Point Mutants to Activate NF-κB—In a recent study (13), we examined the requirements for formation of punctate cytosolic structures, called POLKADOTS, which are highly enriched in Bcl10 and MALT1 and which form in response to stimulation of the TCR and in conjunction with TCR-mediated activation of NF-κB. In that study, we found that formation of POLKADOTS was blocked by mutations that disrupt the proper folding of the Bcl10 CARD, as well as by mutants of Bcl10 or MALT1 that prevent Bcl10-MALT1 complex formation. Thus, point mutants of Bcl10 that have a mis-folded CARD or that fail to associate with MALT1 should not form POLKADOTS in response to TCR stimulation. To assess POLKADOTS formation, we cloned Bcl10-GFP point mutants into retroviral vectors. Viral supernatants were used to infect D10 T cells, and we tested the ability of these mutants to form POLKADOTS in response to TCR stimulation (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Consistent with our previously published data (13, 35), the wild-type Bcl10-GFP formed robust POLKADOTS, whereas the Δ107–119 mutant, which cannot bind to MALT1, and the G78R mutant, which has an unstable CARD and is unable to interact with CARMA1, formed no POLKADOTS.

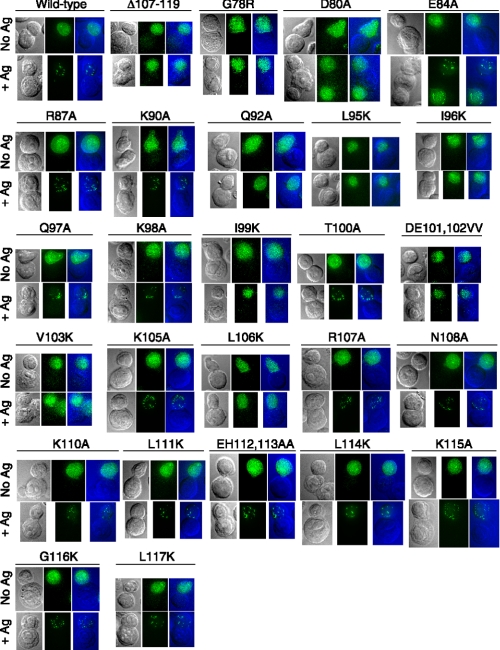

FIGURE 4.

Specific point mutations severely impair antigen-stimulated formation of Bcl10 POLKADOTS. Retroviral vectors expressing point mutants of Bcl10-GFP were used to infect D10 T cells, producing stable polyclonal cell lines. Each cell line was stimulated for 20 min with CH12 B cells that were loaded overnight with 250 μg/ml conalbumin (+Antigen) or with no antigen (No Ag) to induce Bcl10 redistribution into POLKADOTS. Cells were fixed and analyzed to detect Bcl10 POLKADOTS by digital deconvolution epifluorescence microscopy, as previously described (14). Data are also tabulated in Table 1, designating mutants that do and do not form POLKADOTS. Panels are arranged from left to right as differential interference contrat (DIC) image, fluorescence (GFP) image, and overlay image (GFP, green; DIC, blue). Each image is oriented to show a fluorescent T cell (top) and a non-fluorescent antigen presenting cell (bottom).

Importantly, the pattern of POLKADOTS formation correlated very well with the ability of Bcl10 mutants to activate NF-κB. More specifically, any mutant that demonstrated NF-κB activation >25% of WT levels formed POLKADOTS (R87A, K90A, Q97A, K98A, T100A, R107A, N108A, E112A/H113A, L114K, G116K, L117K). Also, mutants with NF-κB activation at or below the level of the negative controls (<7% of WT levels) never formed POLKADOTS (L95K, I96K, I99K, D101V,E102V, V103K). Finally those mutants with weak NF-κB activation, in the range of 7–25% of WT levels, either formed POLKADOTS in the majority of cells (E84A, K105A, K110A, L111K, K115A), or had a minority population of cells that formed small POLKADOTS of reduced intensity (D80A, Q92A, L106K), reminiscent of the POLKADOTS formed by wild-type Bcl10 in response to weak agonist stimulation of D10 T cells (13).

Overall, these results are consistent with our hypothesis that POLKADOTS formation is an integral step in Bcl10-mediated signal transmission from the TCR to NF-κB (13, 14). Signaling-competent forms of Bcl10 always form at least some POLKADOTS in conjunction with signal transmission to NF-κB, whereas non-functional forms of Bcl10 are unable to form POLKADOTS. Those point mutants deficient in POLKADOTS formation would be predicted to fail to associate with MALT1, CARMA1, or both.

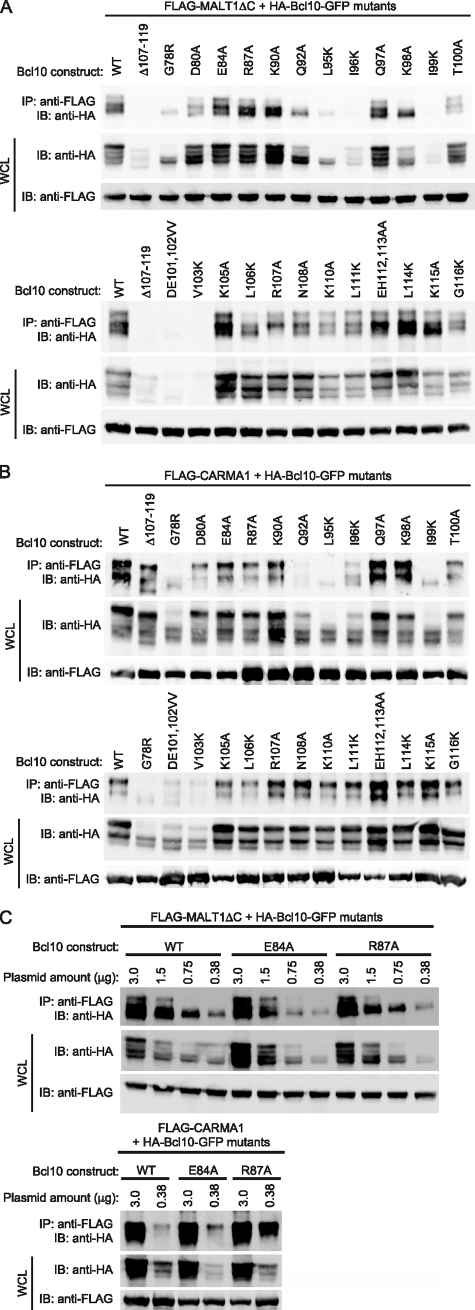

Effect of Point Mutations on Bcl10 Association with MALT1 and CARMA1—To examine the physical association between Bcl10 and MALT1, we performed IP analyses, using HEK293T cells co-transfected with MALT1-ΔC and each of the Bcl10 mutants described above, with the exception of L117K (Fig. 5A). We employed MALT1-ΔC, rather than full-length MALT1, because this fragment of MALT1 contains all domains required for binding to Bcl10, and it is expressed at higher levels than full-length MALT1 (data not shown and Ref. 31). Additionally, to functionally assess whether or not the CARD of each point mutant was properly folded, we performed co-IP analyses with CARMA1 (Fig. 5B), because interactions between Bcl10 and CARMA1 require a properly folded CARD. The IP results are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 5.

Immunoprecipitation analysis of association between MALT1, CARMA1, and Bcl10 point mutants. A, FLAG-MALT1-ΔC and the indicated HA-tagged Bcl10 constructs were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. IP of MALT1 was performed with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Western blotting with an anti-HA antibody to detect co-immunoprecipitated Bcl10. Whole cell lysates (WCL) were also probed with anti-HA and anti-FLAG to evaluate expression of the Bcl10 and MALT1 constructs. B, FLAG-CARMA1 and the indicated HA-tagged Bcl10 constructs were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. IP analyses were performed as in A. C, FLAG-MALT1-ΔC (top gel) and FLAG-CARMA1 (bottom gel) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells with decreasing amounts of the indicated HA-Bcl10 constructs. Total DNA was maintained at 3 μg/transfection by inclusion of pBluscript KS+ (Stratagene), as needed. IP analyses were performed as in A. IB, immunoblot.

Analogous to previous studies assessing interactions between Bcl10, MALT1, and CARMA3 (12), the Δ107–119 negative control for MALT1 binding was unable to associate with MALT1, but showed robust binding to CARMA1. Similarly the G78R negative control for CARMA1 binding was unable to associate with CARMA1. Interestingly, this mutant also bound poorly to MALT1 (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that an intact Bcl10 CARD is required for MALT1 binding. Most mutants were expressed at levels similar to WT, although we consistently noted reduced expression of specific mutants (including the Δ107–119 control and the G78R control), particularly upon cotransfection with MALT1-ΔC. However, titration experiments demonstrated that co-IP of WT Bcl10 occurred efficiently at reduced expression levels (see Fig. 5C). Thus, the IP data could still be interpreted, despite variable expression of Bcl10 mutants in MALT1 cotransfection experiments.

Examination of the IP data suggested three general classes into which the Bcl10 mutants could be grouped (Fig. 5 and Table 1). We also correlated the IP data with the ability of each mutant to form POLKADOTS and to activate NF-κB in reporter assays.

1) Mutants that IP poorly with both MALT1-ΔC and CARMA1 (Q92A, L95K, I96K, I99K, D101V,E102V, and V103K). Without exception, mutants that exhibited poor IP with both CARMA1 and MALT1 also showed <25% NF-κB activation in reporter assays and no POLKADOTS formation (or weak POLKADOTS in a minority population for Q92A). This group also includes the mutants predicted to be important for the structural integrity of the CARD, based on formation of inter-helical contacts (see above). Thus, our interpretation is that this class of mutants indeed represents Bcl10 variants with a destabilized CARD.

2) Mutants that IP poorly with MALT1-ΔC, but efficiently with CARMA1 (D80A, T100A, L106K, R107A, N108A, K110A, L111K, and G116K). Although there was considerable heterogeneity in this group with respect to NF-κB activation and POLKADOTS formation, none of these mutants showed WT levels of NF-κB activation, and the majority fell in the 7–25% range of NF-κB activation. Thus, these data are consistent with the interpretation that this class of mutants has diminished affinity for MALT1 while retaining the ability to efficiently associate with CARMA1. 3) Mutants that IP strongly with both MALT1-ΔC and CARMA1 (E84A, R87A, K90A, Q97A, K98A, K105A, E112A/H113A, L114K, and K115A). Again, there was heterogeneity in this group with respect to NF-κB activation (7–100% of WT levels), although these mutants were uniform in their ability to form POLKADOTS. We propose that the mutants in this class that have WT or close to WT levels of NF-κB activation are able to associate with MALT1 and CARMA1 with WT or near-WT affinity. We, furthermore, hypothesize that the mutants in this class that show clearly diminished NF-κB activation have a deficit in MALT1 or CARMA1 binding that is not apparent at the levels of overexpression achieved in these assays.

To test this hypothesis, we performed IP analysis of titrated levels of three Bcl10 constructs in the presence of constant levels of MALT1-ΔC and CARMA1. As shown in Fig. 5C, the R87A mutant, which efficiently activates NF-κB, showed no deficit in association with either MALT1-ΔC or CARMA1. In contrast, the E84A mutant, which only weakly activates NF-κB, clearly bound more poorly than WT to MALT1-ΔC upon titration of the plasmid, whereas its association with CARMA1 was at least as strong as Bcl10-WT. Thus, the E84A mutant, and possibly other mutants showing reduced NF-κB activation in this group, have a deficit in their ability to associate with MALT1.

Overall, these results demonstrate that the majority of Bcl10 point mutations that reduce NF-κB activation also demonstrably reduce physical association between Bcl10 and MALT1, CARMA1, or both. Notably, any mutation that disrupted the physical integrity of the Bcl10 CARD (as measured by reduced CARMA1 binding) also abolished binding to MALT1-ΔC. Thus, an intact CARD is required for Bcl10 binding to MALT1, strongly suggesting that MALT1 makes physical contact with residues within the Bcl10 CARD, as well as within the 107–119 region (31). Of particular interest is that mutation of Asp80 and Glu84, hydrophilic residues predicted to be solvent-exposed in helix 5 of the Bcl10 CARD (Fig. 2C), leads to substantially reduced NF-κB activation and demonstrably reduced association with MALT1 (without disrupting association with CARMA1). Asp80 and Glu84 thus have properties suggesting that these Bcl10 amino acids directly contact MALT1.

FRET Analysis of Association between Bcl10 Mutants and MALT1 in D10 T Cells—The above biochemical analyses of association between MALT1 and Bcl10 mutants were based on IP of overexpressed proteins in a heterologous cell type (HEK293T cells). Although this is a widely used and generally accepted method of studying protein-protein interactions, there are caveats regarding the data that are generated. First, IP analysis may fail to detect a subset of protein-protein interactions that are too weak to survive the lysis and IP steps, but are nonetheless, relevant in vivo. Second, at the high levels of overexpression achieved in cells such as HEK293T, potential additional (endogenous) binding partners required for stabilization of a given multiprotein complex may not be present at levels great enough to stabilize the complex, or they may be entirely absent if expressed in a tissue-specific manner.

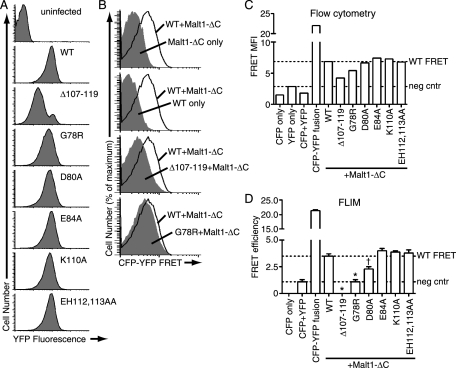

Therefore, to complement our IP data with an analysis of Bcl10-MALT1 association in T cells in vivo, we performed two types of FRET studies. For both types of FRET analyses, stable cell lines were produced by co-infecting D10 T cells with retroviruses encoding MALT1-ΔC-CFP and a Bcl10-YFP construct. The selected Bcl10 mutants included representatives from each of the three mutant classes (Table 1). Notably, the expression level of Bcl10 mutants was more uniform in D10 T cells (Fig. 6A) than in HEK293T cells (see Western blots in Fig. 5A), although the Δ107–119 construct was again poorly expressed relative to Bcl10-WT and other Bcl10 mutants. No discernable differences in expression of MALT1-ΔC-CFP were observed between the various D10 cell lines (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

FRET analysis of association between MALT1 and Bcl10 mutants. A, FACS analysis of YFP fluorescence in D10 T cells co-expressing MALT1-ΔC-CFP and the indicated Bcl10-YFP constructs. B, FACS overlays, showing the FRET channel histograms from the indicated control or experimental cell lines (solid gray) overlaid onto the FRET histogram from the cell line co-expressing MALT1-ΔC-CFP and Bcl10-WT-YFP (black line). C, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the FRET channel from the indicated D10 T cell lines as determined by FACS FRET. Dotted lines indicate the FRET MFI of the negative control exhibiting the highest FRET signal (considered the FRET background value) and the FRET MFI of cells co-expressing MALT1-ΔC-CFP and Bcl10-WT-YFP. D, FRET efficiency as determined by FLIM analysis of the indicated cell lines. Dotted lines indicate the FRET efficiency of the CFP+YFP negative control (indicating the frequency of FRET due to random CFP-YFP collisions) and the FRET efficiency of co-expressed MALT1-ΔC-CFP and Bcl10-WT-YFP. Error bars are S.E. *, p < 0.0001 versus Bcl10-WT-YFP; †, p = 0.0013 versus Bcl10-WT-YFP; all other mutants not significant.

In the first set of studies, we used a flow cytometry FRET approach (47, 48) for comparative analysis of Bcl10-MALT1 interactions. As shown in Fig. 6B, in cells co-expressing MALT1-ΔC-CFP and Bcl10-WT-YFP, the fluorescence in the FRET channel was clearly higher than the signal detected for either construct expressed by itself, demonstrating that we could detect FRET between Bcl10 and MALT1-ΔC using this methodology. In further support of the validity of this approach, a positive control consisting of a direct fusion between CFP and YFP showed very strong FRET channel fluorescence, whereas the negative control of co-expressed (unlinked) CFP and YFP had weak FRET channel fluorescence (Fig. 6C). Analysis of cells co-expressing MALT1-ΔC and a subset of Bcl10 mutants showed that Δ107–119, G78R, and possibly D80A had reduced FRET, relative to WT. In contrast, the E84A, K110A, and E112A/H113A mutants produced a FRET signal at least as strong as Bcl10-WT (Fig. 6, B and C).

In a second set of studies, we performed further FRET analyses employing the same D10 cell lines described above, using fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) to calculate FRET efficiencies. Because FLIM is based on analysis of changes in the lifetime of donor molecules (MALT1-ΔC, in these experiments), it is less sensitive to differences in expression levels of acceptor molecules (Bcl10 constructs) than methods such as the above FACS assay, which are based on detecting transfer of energy to the acceptor (53).

As shown in Fig. 6D, FLIM analysis of the D10 T cell lines produced results that mirrored the FACS FRET data (compare Fig. 6, C and D). Importantly, statistical analysis of the FLIM data showed that the Δ107–119, G78R, and D80A mutants had reduced association with MALT1-ΔC, relative to Bcl10-WT. In contrast, the E84A, E112A/H113A, and K110A mutants were not statistically different from Bcl10-WT. These results were also largely consistent with our biochemical and functional data (Figs. 3, 4, 5, Table 1), although there were notable differences. Specifically, although the K110A and E84A mutants showed substantially reduced NF-κB activation and substantial or slight reductions, respectively, in IP efficiency with MALT1-ΔC in HEK293T cells, the FRET data demonstrate that there is no detectable reduction in association of these mutants with MALT1-ΔC in D10 T cells.

One minor discrepancy in the two methods was that the FRET signal produced by Δ107–119 and G78R was at or below the FRET signal of the negative control (co-expressed CFP and YFP) in the FLIM experiments, but above the negative control in the FACS experiments. We are not certain of the reason for this difference, but we believe the FLIM data are more reliable, because they are independent of concentration of the FRET acceptor (which varied considerably between the YFP-only negative control, the CFP+YFP cell line, Bcl10-WT, and Δ107–119 (Fig. 6A and data not shown)) (53).

Importantly, the FRET data were entirely consistent with the ability of each mutant to form POLKADOTS. Those mutants that showed reduced FRET (Δ107–119, G78R, D80A) also failed to form POLKADOTS, whereas the other constructs (WT, E84A, K110A, E112A/H113A) all exhibited POLKADOTS formation in response to antigen stimulation. Thus, the analyses performed in D10 T cells (FRET studies and measurement of ability to form POLKADOTS) were in complete agreement for each of the Bcl10 constructs examined in this study.

Overall, the above FRET analyses agree with the biochemical and functional data in this study, demonstrating that an intact Bcl10 CARD is required for association with MALT1. In addition, the combined data suggest that the association between Bcl10 and MALT1 in T cells is likely to be influenced by additional factors that are not accounted for by IP analysis of overexpressed proteins in heterologous cells. Furthermore, consistent with our previous data (13), these studies demonstrate that formation of Bcl10 POLKADOTS is highly correlated with functional interactions between Bcl10 and MALT1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a deletion and targeted point mutation strategy to better define the molecular determinants that enable Bcl10 to interact with its signaling partner, MALT1. IP analysis of MALT1 deletion mutants confirmed previous studies (31, 49), showing that the MALT1 Ig-like domains play an essential role in Bcl10-MALT1 complex formation. Importantly, FRET data revealed a previously unrecognized role of the MALT1 DD in mediating in vivo interactions between MALT1 and Bcl10 in T cells. It is possible that both the DD and the Ig-like domains are required for efficient binding to the Bcl10 CARD, but that the DD-Bcl10 interaction is too weak to detect by IP analysis. Alternatively, FRET data could also be explained by the existence of a third partner protein, which contacts both the MALT1 DD and the Bcl10 CARD, but which is not expressed at high enough levels in HEK293T cells to stabilize the interaction between overexpressed Bcl10 and MALT1-ΔC. Further studies will be required to discriminate between these possibilities.

Combined deletion and point mutation analysis of Bcl10 revealed that the previously defined (31) minimal MALT1 interaction site (aa 107–119) includes a cluster of eight amino acids (aa 107–114) that, together, are essential for association with MALT1. In contrast, aa 115–119 are dispensable for NF-κB activation and MALT1 binding, as are all amino acids downstream of aa 119. Point mutagenesis revealed that there is no individual amino acid in the 105–119 region of Bcl10 that is absolutely required for Bcl10-mediated NF-κB activation. However, Leu106, Lys110, and Leu111 are major contributors to NF-κB activation and MALT1 binding (based on heterologous overexpression in HEK293T cells), whereas each of the other tested residues in the 105–119 interval was found to contribute to a lesser degree to NF-κB activation or MALT1 binding. None of these residues are in the Bcl10 CARD, and IP analysis indicated no impact on CARMA1-Bcl10 association. The combined biochemical and luciferase assay data thus argue that all of these mutations impair binding to MALT1.

However, there are other data that are not consistent with such an interpretation. First, four of the mutants in the 105–119 interval (K105A, E112A/H113A, L114K, and K115A) showed no reduction in association with MALT1-ΔC by IP analysis. Additionally, FRET analysis of K110A and E112A/H113A indicated that these mutants are associated with Bcl10 at levels indistinguishable from WT in D10 T cells. Furthermore, analysis of POLKADOTS formation showed functional Bcl10-MALT1 association for each tested point mutant beyond Leu106, demonstrating that no single residue from 107 to 117 has high functional relevance in T cells. Our interpretation of the combined data is thus that, although several amino acids in the 107–114 region are clearly important for stabilizing the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction in the context of overexpression, many of these mutations may have a trivial impact on Bcl10-MALT1 association in T cells in vivo.

One possibility suggested by these data is that there are additional cellular factors that contribute significantly to stabilization of the Bcl10-MALT1 complex in vivo. Combined with the above data regarding the in vivo contribution of the MALT1 DD to stabilization of the Bcl10-MALT1 complex, we believe the data quite strongly suggest the participation of a constitutively associated protein that binds to Bcl10 and MALT1 simultaneously. Whether this putative stabilizing protein is a previously identified partner (e.g. caspase-8 (16, 17)), or an unidentified co-factor in the Bcl10-MALT1 complex will require further biochemical and in vivo studies.

Among residues within the Bcl10 CARD, numerous pieces of evidence are suggestive that Asp80 and Glu84 represent contact sites for MALT1, with Asp80 being particularly important. Both Asp80 and Glu84 are predicted by our homology-based model to lie within helix 5 on the solvent-exposed helix 5–6 face of the Bcl10 CARD (Fig. 2). The D80A mutation severely reduced NF-κB activation and POLKADOTS formation, and this mutation considerably reduced co-IP and FRET with MALT1-ΔN (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, Table 1), without affecting co-IP with CARMA1. E84A also impaired Bcl10-mediated NF-κB activation (although not as strongly as D80A), and this mutation reduced co-IP with MALT1-ΔC (without affecting co-IP of CARMA1) in titration analysis. The observation that E84A formed robust POLKADOTS is consistent with its higher NF-κB activation than D80A (Fig. 3) and stronger association with MALT1 (Figs. 5 and 6).

An additional set of mutants showed only weak co-IP with CARMA1 (G78R, Q92A, L95K, I96K, I99K, D101V/E102V, V103K). Importantly, these mutants also uniformly exhibited weak or no association with MALT1-ΔC. In FRET analyses, the G78R mutant (the only representative of this group tested in FRET experiments) exhibited highly impaired association with MALT1-ΔC in D10 T cells. The lack of strong co-IP with CARMA1 strongly suggests that these Bcl10 mutants have an improperly folded CARD. Although it is formally possible that these mutations affect amino acids that directly contact CARMA1, the location of these residues on the helix 5–6 face argues against this (because known CARD-CARD interactions utilize the helix 1–4 or 2–3 face). Also, most of these residues are predicted by our homology-based model to be predominantly solvent-inaccessible and to make interhelical contacts, again consistent with the interpretation that mutation of these residues would be CARD destabilizing. Thus, our conclusion is that a properly folded CARD is required for Bcl10 to associate with MALT1, as well as CARMA1. Therefore, two independent classes of mutations implicate the Bcl10 CARD as a critical determinant for interaction with the MALT1 N-terminal region.

Together, our data strongly suggest that the interaction between Bcl10 and MALT1 involves both the DD of MALT1 and the CARD of Bcl10, in addition to the Ig-like domains of MALT1 and the 107–119 peptide of Bcl10, which were identified in previous studies (31, 49). Neither the Bcl10 CARD nor the MALT1 DD have previously been implicated in the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction. As the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction is a critical intermediate downstream of a diverse array of NF-κB-coupled receptors, disruption of the Bcl10-MALT1 complex may represent an attractive strategy to selectively block specific NF-κB activation cascades. Our data may help guide strategies for designing drugs to dissociate Bcl10 from MALT1. Finally, in conjunction with the recent observation of the heterotypic interaction between the CARD of ARC (apoptosis repressor with a CARD; also known as CARD2) and the C-terminal domain of Bax (32), our observations suggest that CARD interactions with non-CARD targets may be relevant to many signaling pathways. Based on our analysis of the Bcl10-MALT1 interaction, we speculate that such interactions may preferentially utilize the helix 5–6 face of the CARD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ria Oosterveld-Hut for assistance with collection of FLIM data and instruction regarding data analysis, Dr. Joe Brzostowski for arranging access to the LIFA instrumentation, Drs. Gabriel Nunez, Joel Pomerantz, and David Baltimore for plasmids, and Drs. Joe Giam and Paul Love for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI057481 (to B. C. S.). This work was also supported by a Kimmel Scholar Award from the Sidney Kimmel Society for Cancer Research (to B. C. S.) and a grant from the Dana Foundation Program in Brain and Immunoimaging (to B. C. S.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MALT, mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue; aa, amino acid; CARD, caspase recruitment domain; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; DD, death domain; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein; Ig, immunoglobulin; IP, immunoprecipitation; POLKADOTS, punctate and oligomeric killing or activating domains transducing signals; WT, wild type; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; FLIM, fluorescence lifetime imaging; IKK, IκB kinase; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; HA, hemagglutinin; TCR, T cell receptor.

References

- 1.Schulze-Luehrmann, J., and Ghosh, S. (2006) Immunity 25 701–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegener, E., and Krappmann, D. (2007) Science's STKE 2007, pe21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ruefli-Brasse, A. A., French, D. M., and Dixit, V. M. (2003) Science 302 1581–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruland, J., Duncan, G. S., Elia, A., del Barco Barrantes, I., Nguyen, L., Plyte, S., Millar, D. G., Bouchard, D., Wakeham, A., Ohashi, P. S., and Mak, T. W. (2001) Cell 104 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruland, J., Duncan, G. S., Wakeham, A., and Mak, T. W. (2003) Immunity 19 749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue, L., Morris, S. W., Orihuela, C., Tuomanen, E., Cui, X., Wen, R., and Wang, D. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4 857–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis, T. G., Jadayel, D. M., Du, M. Q., Peng, H., Perry, A. R., Abdul-Rauf, M., Price, H., Karran, L., Majekodunmi, O., Wlodarska, I., Pan, L., Crook, T., Hamoudi, R., Isaacson, P. G., and Dyer, M. J. (1999) Cell 96 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, Q., Siebert, R., Yan, M., Hinzmann, B., Cui, X., Xue, L., Rakestraw, K. M., Naeve, C. W., Beckmann, G., Weisenburger, D. D., Sanger, W. G., Nowotny, H., Vesely, M., Callet-Bauchu, E., Salles, G., Dixit, V. M., Rosenthal, A., Schlegelberger, B., and Morris, S. W. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karin, M., and Ben-Neriah, Y. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18 621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun, Z., Arendt, C. W., Ellmeier, W., Schaeffer, E. M., Sunshine, M. J., Gandhi, L., Annes, J., Petrzilka, D., Kupfer, A., Schwartzberg, P. L., and Littman, D. R. (2000) Nature 404 402–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto, R., Wang, D., Blonska, M., Li, H., Kobayashi, M., Pappu, B., Chen, Y., and Lin, X. (2005) Immunity 23 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAllister-Lucas, L. M., Inohara, N., Lucas, P. C., Ruland, J., Benito, A., Li, Q., Chen, S., Chen, F. F., Yamaoka, S., Verma, I. M., Mak, T. W., and Nunez, G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30589–30597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossman, J. S., Stoicheva, N. G., Langel, F. D., Patterson, G. H., Lippincott-Schwartz, J., and Schaefer, B. C. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 2166–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaefer, B. C., Kappler, J. W., Kupfer, A., and Marrack, P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 1004–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun, L., Deng, L., Ea, C. K., Xia, Z. P., and Chen, Z. J. (2004) Mol. Cell 14 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misra, R. S., Russell, J. Q., Koenig, A., Hinshaw-Makepeace, J. A., Wen, R., Wang, D., Huo, H., Littman, D. R., Ferch, U., Ruland, J., Thome, M., and Budd, R. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 19365–19374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su, H., Bidere, N., Zheng, L., Cubre, A., Sakai, K., Dale, J., Salmena, L., Hakem, R., Straus, S., and Lenardo, M. (2005) Science 307 1465–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egawa, T., Albrecht, B., Favier, B., Sunshine, M. J., Mirchandani, K., O'Brien, W., Thome, M., and Littman, D. R. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13 1252–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaide, O., Favier, B., Legler, D. F., Bonnet, D., Brissoni, B., Valitutti, S., Bron, C., Tschopp, J., and Thome, M. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3 836–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara, H., Wada, T., Bakal, C., Kozieradzki, I., Suzuki, S., Suzuki, N., Nghiem, M., Griffiths, E. K., Krawczyk, C., Bauer, B., D'Acquisto, F., Ghosh, S., Yeh, W. C., Baier, G., Rottapel, R., and Penninger, J. M. (2003) Immunity 18 763–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jun, J. E., Wilson, L. E., Vinuesa, C. G., Lesage, S., Blery, M., Miosge, L. A., Cook, M. C., Kucharska, E. M., Hara, H., Penninger, J. M., Domashenz, H., Hong, N. A., Glynne, R. J., Nelms, K. A., and Goodnow, C. C. (2003) Immunity 18 751–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton, K., and Dixit, V. M. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13 1247–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross, O., Grupp, C., Steinberg, C., Zimmermann, S., Strasser, D., Hannesschlager, N., Reindl, W., Jonsson, H., Huo, H., Littman, D. R., Peschel, C., Yokoyama, W. M., Krug, A., and Ruland, J. (2008) Blood, 112 2421–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malarkannan, S., Regunathan, J., Chu, H., Kutlesa, S., Chen, Y., Zeng, H., Wen, R., and Wang, D. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 3752–3762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross, O., Gewies, A., Finger, K., Schafer, M., Sparwasser, T., Peschel, C., Forster, I., and Ruland, J. (2006) Nature 442 651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hara, H., Ishihara, C., Takeuchi, A., Imanishi, T., Xue, L., Morris, S. W., Inui, M., Takai, T., Shibuya, A., Saijo, S., Iwakura, Y., Ohno, N., Koseki, H., Yoshida, H., Penninger, J. M., and Saito, T. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemm, S., Zimmermann, S., Peschel, C., Mak, T. W., and Ruland, J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 134–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAllister-Lucas, L. M., Ruland, J., Siu, K., Jin, X., Gu, S., Kim, D. S., Kuffa, P., Kohrt, D., Mak, T. W., Nunez, G., and Lucas, P. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 139–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coornaert, B., Baens, M., Heyninck, K., Bekaert, T., Haegman, M., Staal, J., Sun, L., Chen, Z. J., Marynen, P., and Beyaert, R. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rebeaud, F., Hailfinger, S., Posevitz-Fejfar, A., Tapernoux, M., Moser, R., Rueda, D., Gaide, O., Guzzardi, M., Iancu, E. M., Rufer, N., Fasel, N., and Thome, M. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9 272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas, P. C., Yonezumi, M., Inohara, N., McAllister-Lucas, L. M., Abazeed, M. E., Chen, F. F., Yamaoka, S., Seto, M., and Nunez, G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 19012–19019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nam, Y. J., Mani, K., Ashton, A. W., Peng, C. F., Krishnamurthy, B., Hayakawa, Y., Lee, P., Korsmeyer, S. J., and Kitsis, R. N. (2004) Mol. Cell 15 901–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan, M., Schallhorn, A., and Wurm, F. M. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24 596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., and Gibson, T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer, B. C., Mitchell, T. C., Kappler, J. W., and Marrack, P. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 297 86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schaffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley, L. A., MacCallum, R. M., and Sternberg, M. J. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 299 499–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (1997) Electrophoresis 18 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez, R., and Sali, A. (2000) Methods Mol. Biol. 143 97–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luthy, R., Bowie, J. U., and Eisenberg, D. (1992) Nature 356 83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris, A. L., MacArthur, M. W., Hutchinson, E. G., and Thornton, J. M. (1992) Proteins 12 345–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzo, M. A., Springer, G. H., Granada, B., and Piston, D. W. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol. 22 445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griesbeck, O., Baird, G. S., Campbell, R. E., Zacharias, D. A., and Tsien, R. Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 29188–29194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zacharias, D. A., Violin, J. D., Newton, A. C., and Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Science 296 913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, T., and Zhang, J. (2000) J. Virol. 74 7646–7650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan, F. K., Siegel, R. M., Zacharias, D., Swofford, R., Holmes, K. L., Tsien, R. Y., and Lenardo, M. J. (2001) Cytometry 44 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegel, R. M., Chan, F. K., Zacharias, D. A., Swofford, R., Holmes, K. L., Tsien, R. Y., and Lenardo, M. J. (2000) Science's STKE 2000, PL1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Uren, A. G., O'Rourke, K., Aravind, L. A., Pisabarro, M. T., Seshagiri, S., Koonin, E. V., and Dixit, V. M. (2000) Mol. Cell 6 961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber, C. H., and Vincenz, C. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci 26 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chou, J. J., Matsuo, H., Duan, H., and Wagner, G. (1998) Cell 94 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guiet, C., and Vito, P. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148 1131–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Munster, E. B., and Gadella, T. W. (2005) Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 95 143–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]