Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum is a purine auxotroph, salvaging purines from erythrocytes for synthesis of RNA and DNA. Hypoxanthine is the key precursor for purine metabolism in Plasmodium. Inhibition of hypoxanthine-forming reactions in both erythrocytes and parasites is lethal to cultured P. falciparum. We observed that high concentrations of adenosine can rescue cultured parasites from purine nucleoside phosphorylase and adenosine deaminase blockade but not when erythrocyte adenosine kinase is also inhibited. P. falciparum lacks adenosine kinase but can salvage AMP synthesized in the erythrocyte cytoplasm to provide purines when both human and Plasmodium purine nucleoside phosphorylases and adenosine deaminases are inhibited. Transport studies in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing the P. falciparum nucleoside transporter PfNT1 established that this transporter does not transport AMP. These metabolic patterns establish the existence of a novel nucleoside monophosphate transport pathway in P. falciparum.

Malaria is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the tropics with 300-500 million clinical cases and 1.5-2.7 million deaths per year (1). Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites of the Plasmodium genus of which Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most of the fatal cases. The parasite is transmitted between human hosts by Anopheles mosquitoes. Malaria has been treated for many years through chemotherapeutic and vector control strategies, but these have not prevented widespread occurrence. An alarming increase in both the resistance of malaria parasites to drug treatment and in mosquito vectors to insecticides has renewed the demand for the development of new chemotherapeutic strategies (2, 3). Advances in the knowledge of the metabolic and nutritional needs of the parasite offer new potential routes for chemotherapy. Because of the rapid rate of DNA synthesis during the 48-h intraerythrocytic growth phase, targeting purine metabolic pathways is a promising route for novel drug development.

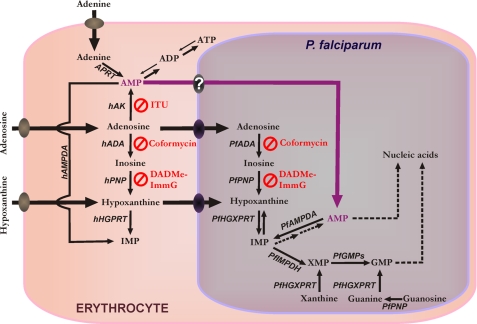

P. falciparum is a purine auxotroph, salvaging host cell purines for synthesis of cofactors and nucleic acids (4, 5). Purine nucleosides and nucleobases can be transported across the parasite plasma membrane by the PfNT12 transporter (Fig. 1). The mechanisms by which Plasmodium salvages purines during the intraerythrocytic cycle are diverse both with regard to primary sources and to routes of interconversion (Fig. 1). Hypoxanthine is the key precursor of other purines in Plasmodium metabolism and is commonly used as a nutritional supplement in malarial culture media. A key source of hypoxanthine in vivo is from the erythrocyte purine pool where ATP is in dynamic metabolic exchange with hypoxanthine via ADP, AMP, IMP, inosine, and adenosine (5). In human erythrocytes, adenosine is efficiently salvaged by adenosine kinase (hAK). This allows human erythrocytes to utilize serum adenosine to maintain erythrocyte ATP levels. In P. falciparum, adenosine is salvaged by conversion to hypoxanthine using adenosine deaminase (PfADA) and purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PfPNP). Hypoxanthine is then converted to IMP by hypoxanthineguanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (PfHGXPRT). PfADA, PfPNP, and PfHGXPRT are highly expressed proteins in the parasite (6, 7). No AK gene has been found in the P. falciparum genome (8). As a result, the parasite cannot directly convert adenosine to AMP.

FIGURE 1.

Purine metabolism in P. falciparum infected-erythrocytes. XMP, xanthosine 5′-monophosphate; hHGPRT, human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; hAMPDA, human adenosine monophosphate deaminase; APRT, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase; PfIMPDH, P. falciparum inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; PfGMPs, P. falciparum guanosine 5′-monophosphate synthase. The metabolic steps inhibited by coformycin, DADMe-ImmG, and ITU are indicated.

P. falciparum cell growth and division demands robust purine salvage, in particular adenosine, because the parasite contains the most (A + T)-rich genome sequenced to date (∼80%). Inhibition of the purine salvage pathway with transition state analogue inhibitors of both human and Plasmodium PNP, such as immucillin-H (ImmH), is lethal for P. falciparum in vitro (9). Coformycin is a picomolar, transition state analogue inhibitor of both human and P. falciparum ADAs (10), and 2′-deoxycoformycin, a related ADA inhibitor, has been reported to have antimalarial potential (11). Previous studies by our laboratory showed that the PNP inhibition by immucillins can be rescued by hypoxanthine but not by inosine (9). Unexpectedly we found that high concentrations of adenosine rescue P. falciparum from PNP inhibition or from combined PNP and ADA inhibition. To understand more fully the purine salvage pathway in P. falciparum, we have characterized adenosine metabolism in this parasite. Here we demonstrate a previously unreported salvage pathway for adenosine in P. falciparum that involves synthesis of AMP by human erythrocyte AK followed by uptake of AMP from the erythrocyte cytosol.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Parasite Cultures

Experiments were performed with the P. falciparum 3D7 clone. Parasites were cultivated according to the method of Trager and Jensen (12) modified by Kimura et al. (13). Parasites were grown in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks in a 5.05% CO2, 4.93% O2, and 90.2% N2 gas mixture at 37 °C (generous gift of Peter C. Tyler, Industrial Research, Ltd., New Iceland). Parasite development and multiplication were monitored by microscopic evaluation of Giemsa-stained thin smears. All metabolic studies were carried out with synchronized parasites in the late trophozoite stage. Cultures were synchronized by two treatments with 5% (w/v) d-sorbitol solution in water (14).

Inhibition Tests

DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (generous gifts of Peter C. Tyler, Industrial Research, Ltd., New Zealand) were dissolved in water. Iodotubercidin (ITU) (Berry and Associates) was dissolved in 100% DMSO. Inhibition tests were carried out in flat bottomed microtiter plates (Costar). The method described by Desjardins et al. (15) was used to determine the IC50 value. Synchronized P. falciparum cultures were grown in purine-rich medium. Prior to the start of experiments they were washed in purine-free medium and cultured in purine-free medium for 24 h. The effect of drugs on parasite growth was measured in a 72-h growth assay in the presence of drug. Ring stage parasite cultures (200 μl/well with 1% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia) were grown for 48 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of each drug. After 48 h in culture, [2,8-3H]hypoxanthine was added at a1 μCi/ml final concentration, and after an additional 24-h incubation period, cells were harvested, and the filters were subjected to liquid scintillation counting. All tests were done in triplicate. Uninfected erythrocytes were used for background determination. Following the same protocol described above, pairwise combinations of DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU were tested at 1:1 molar ratio of increasing drug concentrations.

Adenosine Rescue Assay

To ensure robust erythrocyte function, including AK activity, synchronized, trophozoite stage parasites were magnet-purified (MidiMACS™ Separator, Miltenyi Biotec), washed in purine-free medium to remove excess hypoxanthine, and inoculated into freshly drawn erythrocytes that had been washed and resuspended in purine-free medium. Erythrocytes were obtained from healthy donors under the Committee on Clinical Investigations Protocol M-1063. The trophozoite stage parasites were cultured in purine-free medium for 24 h to further reduce hypoxanthine inside the cell. The resulting ring stage parasites (1% parasitemia, 4% hematocrit) were then incubated with 10 μm inhibitor or DMSO as control for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, parasites (without washing the excess of inhibitor) were diluted into 96-well microtiter plates to a final hematocrit of 2% and increasing adenosine concentrations up to 200 μm and cultured for 48 h. Parasite viability was determined by DNA quantitation as described by Quashie et al. (16). For each condition, three experiments were carried out in duplicate.

[5′-33P]Adenosine Monophosphate Synthesis

Radiolabeled [5′-33P]AMP was synthesized enzymatically with recombinant Anopheles gambiae adenosine kinase (AgAK)3 using 1 μm unlabeled adenosine and 3.3 μm [γ-33P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.) in reaction buffer containing 5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, and 50 mm Tris (pH 7.4) in 200 μl. The reaction was started by addition of 0.25 μm AgAK, incubated at 27 °C for 10 min, and stopped by filtering through a YM10 Centricon column (molecular weight retention, 10,000; Amicon). The filtrate was immediately purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Nucleosil 4000-7 polyethyleneimine column (250 × 4 mm, Macherey-Nagel). The mobile phases were 20 mm Tris base (pH 8.5) as solution A, 20 mm Tris base (pH 8.5) and 1 m KCl (pH 8.5) as solution B, and 10% methanol as solution C. The HPLC gradient was from 0 to 100% solution B in 32 min and 6 min at 100% solution C. The eluant was monitored at 254 nm, and the flow rate was 1 ml/min. Aliquots were collected based on retention time of nucleoside standards previously detected by UV absorption, and an aliquot was subjected to liquid scintillation counting. Under the conditions described above ≥97% of adenosine was converted to [5′-33P]AMP (0.74 × 1012 cpm/mmol).

[1′-3H]Adenosine Synthesis

Adenosine radiolabeled on the ribose ring was synthesized from labeled ribose (17, 18). Briefly [1′-3H]ribose (300 μCi/μmol final concentration, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.) was added to a solution containing 2 mm adenine, 1 mm unlabeled ribose (final concentration), 20 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.1 mm ATP, 100 mm phosphate, 50 mm glycylglycine, 50 mm KCl, 20 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm dithiothreitol (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by addition of an enzyme mixture of 0.01 unit of ribokinase, 0.01 unit of adenine phosphoribosyltransferase, 0.01 unit of phospho-d-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphate synthase, 1 unit of adenylate kinase (Sigma), and 1 unit of pyruvate kinase (Sigma). Ribokinase, phospho-d-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphatesynthase, and adenine phosphoribosyltransferase were purified according to the methods reported previously (17, 18). The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 12 h to give [1′-3H]ATP. The reaction was then quenched by heating at 95 °C for 3 min. To this solution 5 mm glucose, 4 units of hexokinase (Sigma), 5 units of adenylate kinase, and 10 units of alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Science) were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 6 h to allow the conversion of [1′-3H]ATP to [1′-3H]adenosine. [1′-3H]Adenosine was purified twice by reverse phase HPLC (C18 Deltapak column) using 7.5% MeOH, H2O at 1 ml/min (retention time, 14 min). Solvent was removed by SpeedVac. [1′-3H]Adenosine yield was 80% on the basis of the labeled ribose. Aqueous stock solution of 300 μm [1′-3H]adenosine was prepared and stored at -20 °C before use.

Metabolic Labeling

The experiments with radiolabeled metabolic precursors were performed using two different protocols. The purity of all radiolabeled precursors was verified by HPLC. All experiments were performed at 37 °C, including pretreatment with the inhibitors and metabolic labeling in the presence of the drugs.

Protocol 1: Metabolic Labeling in Infected Erythrocytes—Synchronous cultures of P. falciparum in schizont stage with ∼30% parasitemia were diluted into fresh erythrocytes that were either untreated or pretreated with a 10 μm concentration of each inhibitor for 2 h and washed to remove excess inhibitors (summarized in Table 1) before P. falciparum-infected cells were added. After two intraerythrocytic cycles of cell division (96 h), inhibitors were added to the cultures to a 10 μm final concentration of each desired inhibitor. Cultures were incubated for 1 h with inhibitors followed by addition of 1 μm [2-3H]adenosine (23 Ci/mmol, Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h in the presence of inhibitors in purine-free medium. Intraerythrocytic parasites were separated from the host red blood cells (RBCs) by incubating pelleted infected RBCs with 20 pellet volumes of 0.03% saponin in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, CellGro; 2.7 mm KCl, 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 136.9 mm NaCl, and 8.1 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4)) to lyse the RBCs followed by washing in DPBS. This treatment does not permeabilize the parasite plasma membrane (19). Parasites, free of RBCs, were immediately extracted as described below for subsequent HPLC analysis of purine metabolites.

TABLE 1.

Treatments for metabolic studies on infected erythrocytes (Protocol 1)

| RBC pretreatment with 10 μm each inhibitor before infection | Infection | Treatment after infection and during [2-3H]adenosine labeling with 10 μm each inhibitor |

|---|---|---|

| No inhibitor | No | No inhibitor |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin | No | No inhibitor |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU | No | No inhibitor |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin | Yes | No inhibitor |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin | Yes | DADMe-ImmG + coformycin |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin | Yes | DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU | Yes | No inhibitor |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU | Yes | DADMe-ImmG + coformycin |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU | Yes | DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU |

To assay purine metabolism in the erythrocyte cytoplasm and to demonstrate that the initial 2-h inhibitor pretreatment of the erythrocytes persisted throughout the entire experimental protocol, uninfected erythrocytes were pretreated with inhibitors for 2 h under the same conditions as described above, washed to remove non-incorporated inhibitors, incubated for 96 h, and metabolically labeled by addition of 1 μm [2-3H]adenosine (23 Ci/mmol, Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h in the absence of inhibitors in purine-free medium. To assay the purine metabolites present in the uninfected erythrocytes, cells were extracted as described below for subsequent HPLC analysis of purine metabolites. Three independent experiments were carried out for each condition.

Protocol 2: Metabolic Labeling in Intact Erythrocyte-free Parasites—Synchronous cultures of P. falciparum in early schizont stage with ∼20% parasitemia were isolated from their host erythrocytes by incubating pelleted infected RBCs with 20 pellet volumes of 0.03% saponin in DPBS (19). The released parasites were washed three times with DPBS at room temperature. Isolated parasites were resuspended in prewarmed DPBS containing 2 mm glucose. Parasites were incubated for 30 min with or without a 10 μm concentration of the desired inhibitors and metabolically radiolabeled for 1 h with 1 μm [2-3H]adenosine (23 Ci/mmol), [1′-3H]adenosine (300 μCi/μmol), [2-3H]AMP (18 Ci/mmol, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.), [γ-33P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.), or [5′-33P]AMP (0.74 × 1012 cpm/mmol). After incubation, parasites were centrifuged, washed twice with ice-cold DPBS, and lysed by resuspension in water. Parasite samples were immediately extracted as described below for subsequent HPLC analysis of purine metabolites. All tests were repeated at least three times in duplicate.

Extraction of Purine Metabolites

Proteins and nucleic acids were removed by perchloric acid treatment. Samples were treated with 0.5 m HClO4 at 1:6 (v/v), vigorously mixed, and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C. Samples were neutralized with 5 m KOH for 20 min at 4 °C and then filtered through a YM10 Centricon spin column (molecular weight retention, 10,000; Amicon). Aliquots of each extract were monitored for radioactivity with a 1414 Winspectral scintillation counter (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD).

Analysis of Purine Intermediates by HPLC

All samples were analyzed in a reverse phase (Luna C18(2), 150 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm, Phenomenex) ion pair HPLC system. The mobile phases were 8 mm tetrabutylammonium bisulfate (Fluka) and 100 mm KH2PO4 with the pH adjusted to 6.0 with KOH (solution A) and 30% acetonitrile containing 8 mm tetrabutylammonium bisulfate and 100 mm KH2PO4 (pH 6) as solution B. The HPLC gradient was from 0 to 100% solution B in 20 min. The eluant was monitored at 254 nm, and the flow rate was 1 ml/min. Aliquots were collected based on UV detection of nucleoside internal standards and subjected to liquid scintillation counting. The same number of treated or untreated parasites was analyzed in each experiment for comparison of inhibitor effects.

Expression of PfNT1 in Xenopus laevis Oocytes

The PfNT1 gene product was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA preparations of P. falciparum 3D7 strain parasites as described previously (20-22). The sense primer contained a BamH1 site (underlined) prior to the initiating Met (boldface) (5′-CGAGGATCCATGAGTACCGGTAAAGAGTC-3′), whereas the antisense primer contained an EcoR1 site (underlined) down-stream from the termination codon (boldface) (5′-CGAGAATTCTTATTGTGTTACAT-CGATGGGTGG-3′). The PfNT1 PCR product was cloned into a pXOON expression vector (19), and the fidelity of the complete PfNT1 DNA sequence was verified by DNA sequencing. The pXOON plasmid was linearized with NheI, and capped mRNA was prepared using T7 RNA polymerase (mMessage mMachine, Ambion).

Defolliculated X. laevis oocytes were prepared as described previously (23). Oocytes were stored at 16 °C in SOS medium (82.5 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.5)) containing 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen) and 5% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Twenty-four hours postisolation, oocytes were injected with 23 nl of 1 ng/nl PfNT1 capped mRNA dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Nucleoside uptake assays were performed 3 days postinjection.

Nucleoside Uptake in Oocytes Expressing PfNT1

PfNT1-mediated uptake of 1.5 μm [2-3H]adenosine (23 Ci/mmol), [2-3H]AMP (18 Ci/mmol), or [5′-33P]AMP (0.74 × 1012 cpm/mmol) was determined in E1 buffer (140 mm NaCl, 2.8 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4)) or DPBS (Invitrogen). Three to five oocytes per condition were washed with E1 or DPBS buffer, then added to buffer containing radiolabeled nucleoside, and incubated at room temperature for 5, 15, 30, or 60 min. Controls for oocyte membrane surface ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity were performed by addition of 250 μm α,β-MeADP (Sigma) to the oocytes 2 min prior to the initiation of uptake and maintained during the uptake assay. Transport experiments were terminated by five washes with ice-cold E1 or DPBS buffer followed by solubilization of the oocyte with 200 μl of 5% SDS. Samples were subjected to liquid scintillation counting. All data points represent the average of at least 10 individual oocytes derived from at least two separate oocyte isolations.

RESULTS

Effect of PNP, ADA, and AK Inhibitors on P. falciparum Growth—Growth inhibition of P. falciparum 3D7 strain in cultures was measured by [3H]hypoxanthine incorporation in 72-h experiments for treatment with DADMe-ImmG (an inhibitor for both human and parasite PNPs), coformycin (an inhibitor of both human and parasite ADAs), and ITU (a human AK inhibitor). Each inhibitor was tested individually to establish whether the combinations at a 1:1 molar ratio used in the metabolic studies have a synergistic or an antagonistic effect on P. falciparum growth. DADMe-ImmG had the lowest IC50 value (164 nm). ITU also inhibited parasite growth (IC50, 2 μm), but coformycin alone, up to a concentration of 400 μm, did not inhibit the P. falciparum growth after a 72-h treatment (Table 2). No synergism or antagonism was observed at a 1:1 molar ratio of increasing drug concentrations compared with DADMe-ImmG treatment alone.

TABLE 2.

Effect of purine salvage inhibitors on growth of P. falciparum in purine-free medium

| Inhibitor | Target | IC50 |

|---|---|---|

| nM | ||

| DADMe-ImmG | Human and Plasmodium PNP | 164 ± 20 |

| Coformycin | Human and Plasmodium ADA | No growth inhibition |

| ITU | Human AK | 2000 ± 600 |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin | 156 ± 14 | |

| DADMe-ImmG + coformycin + ITU | 163 ± 14 |

Although coformycin alone did not inhibit P. falciparum growth, it was used in metabolic analyses. Metabolic labeling studies showed that coformycin treatment of erythrocyte-free parasites and uninfected normal erythrocytes inhibited human and parasite ADA (data not shown).

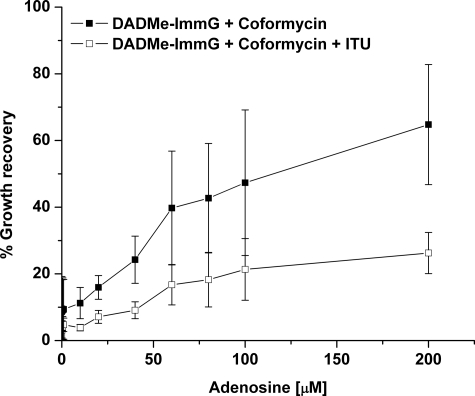

Effect of Adenosine on P. falciparum Growth following PNP and ADA Blockade—To test whether P. falciparum growth in the presence of PNP and ADA inhibitors can be rescued by adenosine, parasite cultures were treated with 10 μm of each inhibitor in combination with increasing concentrations of adenosine (Fig. 2). Adenosine restored 70% of normal P. falciparum growth from the simultaneous block of ADA (coformycin) and PNP (DADMe-ImmG), but addition of ITU significantly reduced the extent of adenosine rescue to 20% of normal growth. No differences were observed between experiments using freshly drawn blood or using blood stored at 4 °C prior to use, indicating independence from stored erythrocyte effects (data not shown). The observation that adenosine can rescue P. falciparum from inhibition of both human and Plasmodium ADA and PNP could be explained by two hypotheses: (a) AK activity in the parasite allowing conversion of adenosine to AMP and/or (b) parasite utilization of AMP and/or ADP and ATP synthesized from adenosine in the erythrocyte cytoplasm.

FIGURE 2.

Adenosine supplementation and recovery of growth in P. falciparum cultures treated with 10 μm DADMe-ImmG, 10 μm coformycin, and 10 μm ITU. Infected erythrocytes were cultured in the absence of exogenous purines followed by incubation in the presence of the inhibitors and the indicated concentrations of adenosine for 48 h followed by DNA quantitation as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” Percent growth recovery is (DNA synthesized by treated cells/DNA synthesized by control cells) × 100. Error bars are the S.D. from three independent experiments.

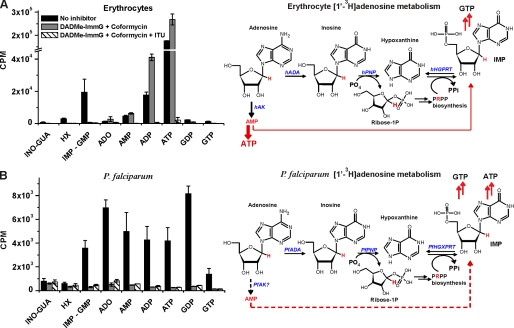

Absence of Adenosine Kinase Activity in P. falciparum—No AK gene has been found in the P. falciparum genome (8), and a very low AK activity was reported (6). Adenosine salvage through ADA and PNP enzymes involves generation of hypoxanthine by removal of the ribose ring, which is used for 1-phosphoribosyl-5-pyrophosphate (PRPP) synthesis. PRPP is then incorporated into hypoxanthine to generate IMP by PfHGX-PRT in parasites and by human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase in erythrocytes (Fig. 3). Only parasites can generate AMP from IMP because human erythrocytes, unlike other human cells, lack adenylosuccinate synthetase, which is necessary for transforming IMP into AMP (24). In the presence of ADA and PNP inhibitors, labeled AMP can only be formed from [1′-3H]adenosine if an adenosine kinase activity is present in the parasite. To test this hypothesis, uninfected erythrocytes and erythrocyte-free parasites were incubated for 30 min with or without a 10 μm concentration of the desired inhibitors and metabolically radiolabeled for 1 h with 1 μm [1′-3H]adenosine.

FIGURE 3.

Metabolism of [1′-3H]adenosine in erythrocytes and in isolated P. falciparum cells to assess adenosine kinase activity. In A, control erythrocytes or erythrocytes treated with 10 μm DADMe-ImmG and coformycin or 10 μm DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU were labeled with [1′-3H]adenosine in the presence of inhibitors. In B, control or treated P. falciparum parasites isolated from erythrocytes by saponin treatment were labeled with [1′-3H]adenosine in the presence of inhibitors. Means ± S.D. from three independent experiments are represented. [1′-3H]Adenosine in erythrocyte-free parasites is incorporated in the ADA + PNP pathway. The erythrocyte and P. falciparum adenosine metabolism schemes show the routes of the tritium (in red) through these pathways. In erythrocytes, [1′-3H]adenosine is metabolized through hAK mainly to ATP independent of hADA and hPNP inhibition. In isolated P. falciparum, when PfADA and PfPNP are inhibited [1′-3H]adenosine could be metabolized to AMP only if a functional PfAK is present in the parasites. The low counts detected in the hypoxanthine peak are attributed to co-elution of a peak for ribose 1-phosphate (Ribose-1P). hHGPRT, human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; ADO, adenosine; GUA, guanosine; INO, inosine; HX, hypoxanthine.

In RBCs untreated with inhibitors, metabolic labeling with [1′-3H]adenosine resulted in incorporation of label into IMP + GMP, ADP, and ATP (Fig. 3A, black bars). As expected, hADA and hPNP blockade resulted in label incorporation only into AMP, ADP, and ATP (Fig. 3A, gray bars). Inhibition of AK by treatment with ITU together with ADA and PNP inhibitors inhibited all [1′-3H]adenosine incorporation into AMP or any other purine metabolites (Fig. 3A, hashed bars). This is consistent with AK activity in human erythrocytes.

Incubation of intact erythrocyte-free parasites with [1′-3H]adenosine showed active incorporation of the labeled ribosyl group into all nucleotides (Fig. 3B, black bars). In the presence of ADA and PNP inhibitors incorporation of [1′-3H]adenosine into all nucleotides was inhibited (Fig. 3B, gray bars). Thus, parasites incorporate the ribosyl group from adenosine by the actions of PfADA, PfPNP, and PfHGXPRT with the [1′-3H]ribosyl 1-phosphate being incorporated via PfPRPP synthase and PfHGXPRT (Fig. 3B, compare black and gray bars). Addition of the AK inhibitor ITU (Fig. 3B, hashed bars) had no significant effect on adenosine uptake (Fig. 3B, compare gray and hatched bars), providing additional support for the lack of a functional AK in P. falciparum.

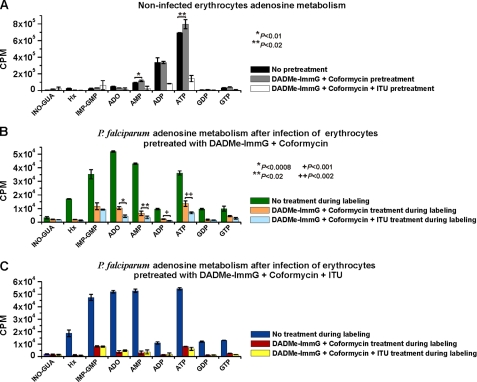

Effect of Inhibitors on Adenosine Metabolism in Normal Red Blood Cells—Adenosine metabolism in uninfected erythrocytes can occur via deamination (hADA) followed by phosphorolysis (hPNP) to hypoxanthine or by direct conversion to AMP by hAK. Erythrocytic fates of [2-3H]adenosine are critical for subsequent metabolism in the parasite (Fig. 1). Inhibitors of erythrocyte hADA (coformycin), hPNP (DADMe-ImmG), and hAK (ITU) were used to block these paths of purine metabolism. This experiment was also designed as a control to assure that after 96 h of postparasite infection, the hADA, hPNP, and hAK enzymes were still inhibited because the aim of the experiment shown in Fig. 4 was to analyze the adenosine fate in P. falciparum when adenosine cannot be metabolized by the erythrocyte. Inhibitors were added at 10 μm in relative excess to the tight binding of these inhibitors (>125,000 × Kd for ADAs, >106 × Kd for PNPs, and 330 × Kd for AK). After 2 h of incubation the excess was removed by washing. Following the 96-h incubation in the absence of free drug under the same conditions used for infected erythrocytes, the metabolic labeling with [2-3H]adenosine was performed without addition of inhibitors. Erythrocytes that were not pretreated with inhibitors showed incorporation of the tritiated label into all nucleotide and nucleoside pools but mainly into AMP, ADP, and ATP (Fig. 4A, black bars). The combination of ADA and PNP inhibition caused a small but significant stimulation of [2-3H]adenosine incorporation into the erythrocyte adenylate pool (Fig. 4A, gray bars compared with black bars). Therefore, hAK is the major salvage pathway for [2-3H]adenosine in erythrocytes under these conditions. The action of hADA and hPNP on [2-3H]adenosine is minor. Addition of all three inhibitors to block hADA, hPNP, and hAK almost completely blocked [2-3H]adenosine incorporation into the erythrocyte nucleotide/nucleoside pool (Fig. 4A, white bars). The small hAK activity detected indicates that a small fraction of ITU was released from hAK during the 96-h incubation. When ITU was added to RBCs during [2-3H]adenosine labeling, >95% of the hAK activity was inhibited (data not shown). This confirms the importance of hAK for adenosine salvage in erythrocytes and the persistent effect of the inhibitors during the time course of the experiments.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of inhibitors on adenosine metabolism in normal and infected erythrocytes. Erythrocytes and infected erythrocytes untreated or treated with 10 μm of each inhibitor were labeled with [2-3H]adenosine. In A, erythrocytes were incubated for 2 h in the absence (black bars) or presence of DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (gray bars) or DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU (white bars) with excess inhibitor removed by washing. After 96 h, cells were incubated with [2-3H]adenosine for 2 h in the absence of inhibitors. In B, erythrocytes were pretreated with DADMe-ImmG and coformycin, washed to remove the excess inhibitors, infected, and after 96 h postinfection labeled with [2-3H]adenosine for 2 h in the absence (green bars) or presence of DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (orange bars) or DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU (light blue bars). Inhibitors were added 1 h prior to metabolic labeling. Parasites were released by saponin treatment, and purine metabolites were extracted from the isolated parasites. In C, erythrocytes were pretreated with DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU; washed to remove the excess inhibitors; infected; and after 96 h postinfection labeled with [2-3H]adenosine for 2 h in the absence (blue bars) or presence of DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (red bars) or DADMe-ImmG, coformycin, and ITU (yellow bars). Inhibitors were added 1 h prior to metabolic labeling. Parasites were released by saponin treatment, and purine metabolites were extracted from the isolated parasites. Means ± S.D. from three independent experiments are represented. The significant p values by Student's t test are also indicated. ADO, adenosine; GUA, guanosine; INO, inosine; Hx, hypoxanthine.

Effect of RBC Pretreatment with ADA + PNP or ADA + PNP + AK Inhibitors on Adenosine Metabolism in P. falciparum—Metabolism of [2-3H]adenosine by parasites was investigated in erythrocytes pretreated with ADA + PNP (Fig. 4B) or ADA + PNP + AK (Fig. 4C) inhibitors to suppress adenosine metabolism by the host cells. Erythrocytes were pretreated with the inhibitors, and excess inhibitor was washed away before infection with P. falciparum. Parasites grew for 96 h in these inhibitor-pretreated erythrocytes, and the resulting infected erythrocytes were metabolically labeled with [2-3H]adenosine either in the absence or presence of ADA + PNP or ADA + PNP + AK inhibitors to inhibit parasite enzymes and to establish differences in parasite metabolism with and without hAK inhibition in the host cells. Following metabolic labeling, parasites were isolated from RBCs by saponin lysis, and the parasite cytoplasm was analyzed for the metabolic fate of [2-3H]adenosine.

Growing parasites readily converted [2-3H]adenosine into hypoxanthine, IMP (+GMP), adenosine, AMP, ADP, ATP, GDP, and GTP even when the hADA, hPNP, and hAK enzymes in the RBCs were inhibited by pretreatment (Fig. 4, B, green bars, and C, dark blue bars). This pattern is readily explained by active PfADA, PfPNP, and PfHGXPRT in the parasites (Fig. 1). These results indicate that the parasite enzyme pool is tightly partitioned from the inhibitors in the RBC cytoplasm because purine synthesis in the parasite is not inhibited by pretreatment of the RBCs.

Pretreatment of the RBCs with ADA + PNP inhibitors and addition of ADA and PNP inhibitors during the metabolic labeling with [2-3H]adenosine to inhibit the corresponding parasite enzymes resulted in incorporation of label into parasite adenosine, AMP, ATP, IMP (+GMP), and GTP (Fig. 4B, orange bars). The level of label incorporation was reduced compared with parasites labeled in the absence of inhibitors (Fig. 4B, green versus orange bars). Addition of the AK inhibitor ITU during the metabolic labeling period in addition to the ADA and PNP inhibitors caused a further decrease in the incorporation of the labeled adenosine into parasite adenosine, AMP, ADP, and ATP (Fig. 4B, light blue versus orange bars). Because the parasites lack AK activity the reduction caused by addition of ITU during the metabolic labeling step represents an effect of ITU on inhibition of erythrocyte AK. Thus, labeled adenosine is converted to AMP by erythrocyte AK, and then AMP is transported into the parasite cytoplasm where it enters the purine salvage pathway beyond the PfADA and PfPNP steps (Fig. 1).

In RBCs pretreated with ADA + PNP + AK inhibitors (Fig. 4C) and during the metabolic labeling step, treatment with ADA + PNP (Fig. 4C, red bars) or ADA + PNP + AK (Fig. 4C, yellow bars) had a similar effect, near complete suppression of label incorporation into the parasite nucleotide pool (Fig. 4C, red/yellow versus dark blue bars). Thus, parasites grown in RBCs pretreated with the AK inhibitor showed no response to the addition of AK inhibitor during metabolic labeling of the parasites. This is consistent with the effect of the AK inhibitor acting only at the level of erythrocytic AK. ITU had little effect on parasite metabolism, consistent with the absence of a functional AK in P. falciparum. ADA and PNP inhibitors added to inhibit parasite enzymes in the presence of [2-3H]adenosine blocked over 90% of all uptake when erythrocyte hAK was also inhibited (Fig. 4C, red versus dark blue bars). Therefore, erythrocytic hAK plays an essential role in adenosine rescue of P. falciparum following ADA and PNP inhibition.

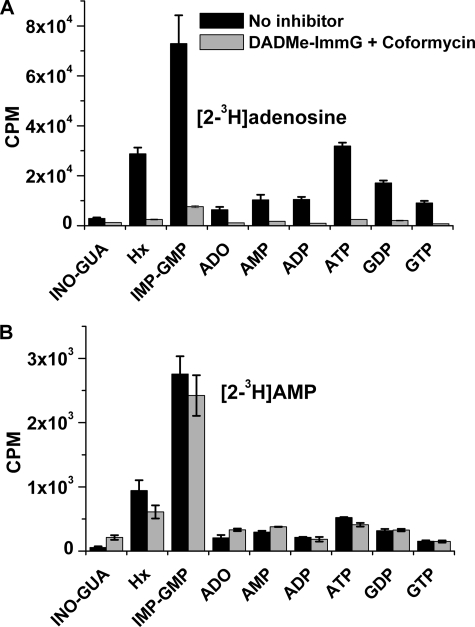

Adenosine and Adenosine Monophosphate Metabolism in Erythrocyte-free P. falciparum—Adenosine can rescue intraerythrocytic parasites from ADA and PNP blockade at elevated, nonphysiological concentrations although there is no AK activity in the parasite (Fig. 3). We tested the ability of isolated parasites to salvage AMP using [2-3H]AMP as metabolic precursor. [2-3H]Adenosine was used as a control to confirm the efficacy of ADA and PNP inhibition during the experiment (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of inhibitors on adenosine metabolism in isolated P. falciparum. Parasites were released by saponin treatment from the erythrocytes. Isolated parasites were metabolically labeled for 1 h with [2-3H]adenosine (A) or [2-3H]AMP (B) in the absence of inhibitors (black bars) or in the presence of 10 μm of DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (gray bars). Means ± S.D. from 4 independent experiments are represented. ADO, adenosine; GUA, guanosine; INO, inosine; Hx, hypoxanthine.

The metabolism of [2-3H]adenosine in isolated parasites was compared with that in parasites treated with ADA and PNP inhibitors during metabolic labeling (Fig. 5A). In the absence of inhibitors [2-3H]adenosine was readily converted to hypoxanthine, IMP (+GMP), AMP, ADP, ATP, GDP, and GTP, establishing a robust pathway through PfADA, PfPNP, PfHGXPRT, and subsequent enzymes of purine nucleotide synthesis (Fig. 5A, black bars). Inhibiting PfADA and PfPNP blocked >90% of all adenosine incorporation (Fig. 5A, gray versus black bars) in this erythrocyte-free system, similar to the results obtained with infected erythrocytes pretreated with ADA + PNP + AK inhibitors (Fig. 4C). Under the same conditions, [2-3H]AMP was incorporated and metabolized to the same extent independent of the PfADA and PfPNP blockade (Fig. 5B, black versus gray bars). Thus, P. falciparum can take up external [2-3H]AMP and convert it to intracellular IMP by P. falciparum AMP deaminase (PfAMPDA) (Fig. 1). IMP is the branch point for synthesis of all other parasite purine nucleotides. Parasites can also convert [2-3H]AMP to hypoxanthine despite the PfADA and PfPNP block. Hypoxanthine (Hx) formation occurs from IMP via the readily reversible reaction of PfHGXPRT (IMP + PPi ↔ Hx + PRPP) (Fig. 1). These steps depend only on PfAMPDA and PfHGXPRT; therefore ADA and PNP inhibitors do not block this process (Fig. 5B).

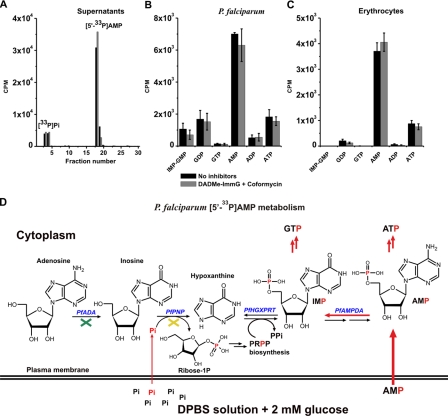

Transport of Adenosine Monophosphate into Intact Erythrocyte-free P. falciparum—The incorporation of [2-3H]AMP in isolated parasites does not eliminate the possibility that dephosphorylation and rephosphorylation might occur during the process. Therefore, [5′-33P]AMP was used as metabolic precursor under the same conditions as [2-3H]AMP to determine whether transport occurs as the 5′-monophosphate.

Because P. falciparum has an inorganic phosphate transporter (25) and hydrolysis of [5′-33P]AMP may occur at 37 °C (Fig. 6A), DPBS solution was used to prevent the uptake of any [33P]Pi that might have been released because of the hydrolysis of AMP during the course of the metabolic labeling. The presence of 9.6 mm phosphate (1.5 mm KH2PO4 and 8.1 mm Na2HPO4) in the DPBS solution prevents the [33P]Pi uptake because this amount dilutes the label by a factor of more than 106 and exceeds the Km for the Pi transporter by ∼100-fold. Under this condition, [5′-33P]AMP was transported into P. falciparum and metabolized mainly to ATP, GDP, and IMP (+GMP) (Fig. 6B, black bars). Addition of ADA and PNP inhibitors during metabolic labeling had no effect on [5′-33P]AMP metabolism (Fig. 6B, gray versus black bars), the same as for [2-3H]AMP (Fig. 5B). A transport and metabolic pathway exists in the parasites independent of PfADA and PfPNP. Control experiments with [5′-33P]AMP incubation with washed erythrocytes also demonstrated AMP uptake and metabolism to ATP without loss of the 5′-phosphate (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

[5′-33P]AMP uptake and metabolism in isolated P. falciparum and in uninfected erythrocytes. In A, supernatants from parasite incubation (in B) were analyzed by HPLC, and all fractions were analyzed for 33P. Only one chromatogram from each condition, control (black bars) and treated (gray bars), is represented. In B, parasites were incubated for 30 min without inhibitors (black bars) or with 10 μm DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (gray bars) and metabolically radiolabeled for 1 h with [5′-33P]AMP, washed, extracted, and analyzed for 33P-labeled metabolites. In C, uninfected erythrocytes were incubated for 30 min without inhibitors (black bars) or with 10 μm DADMe-ImmG and coformycin (gray bars) and then metabolically labeled with [5′-33P]AMP. Means ± S.D. from three independent experiments are represented. In D, a scheme of P. falciparum [5′-33P]AMP metabolism indicates how the phosphorus atom (in red) is metabolized through the purine pathway under these experimental conditions (metabolic labeling, Protocol 2). The green cross indicates PfADA inhibition by coformycin, and the yellow cross indicates PfPNP inhibition by DADMe-ImmG.

Control uptake experiments were accomplished with [γ-33P]ATP to investigate specificity for AMP and/or the possibility that isolated parasites were leaky to exogenous nucleotides. Previous reports showed that P. falciparum can transport ATP and ADP across the plasma membrane, but no relationship between the nucleotide transport and purine metabolism was established (26, 27). Under the experimental conditions used here for AMP uptake, no significant uptake of [γ-33P]ATP was observed (data not shown).

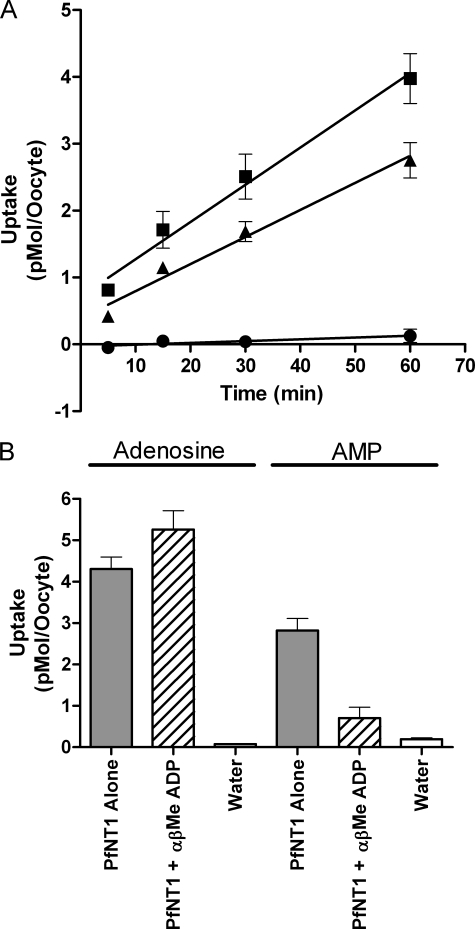

Analysis of AMP Transport via the PfNT1 Nucleoside Transporter Expressed in X. laevis Oocytes—Within the P. falciparum genome, four genes have been identified by sequence homology as putative nucleoside transporters (28). One of these gene products, PfNT1, has been characterized and was shown to be localized in the parasite plasma membrane (29). PfNT1 exhibits a broad specificity for purine nucleosides and nucleobases (20, 21, 30, 31), but the ability of PfNT1 to transport adenine nucleotides has not been reported.

X. laevis oocytes were injected with PfNT1 mRNA and incubated for 3 days to allow for PfNT1 protein synthesis. The PfNT1-expressing and control oocytes were then analyzed for uptake of [2-3H]adenosine or [2-3H]AMP (Fig. 7A). For all experiments, the external nucleoside or nucleotide concentration was 1.5 μm. As reported previously, oocytes expressing PfNT1 exhibited enhanced uptake of [2-3H]adenosine as compared with water-injected oocytes. Moreover PfNT1 also appeared to mediate the uptake of [2-3H]AMP into oocytes. However, the presence of ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity on the oocyte surface has been reported, suggesting the possibility that AMP may be converted to adenosine at the oocyte surface (32, 33). The newly formed adenosine could then be transported into the oocyte by PfNT1. To examine this possibility, the transport of [5′-33P]AMP was measured. No uptake of [5′-33P]AMP into the oocytes was detected (Fig. 7A). Treatment of oocytes with α,β-MeADP, an inhibitor of the oocyte membrane surface ecto-5′-nucleotidase (34), significantly inhibited PfNT1-mediated uptake of [2-3H]AMP but exhibited no effect upon [2-3H]adenosine uptake (Fig. 7B). Therefore, PfNT1 is not capable of transporting AMP and is not the route of entry for AMP into P. falciparum.

FIGURE 7.

Expression of PfNT1 in X. laevis oocytes and analysis of AMP transport. A, time course for PfNT1-mediated uptake of 1.5 μm [2-3H]adenosine (▪), [2-3H]AMP (▴), or [5′-33P]AMP (•). PfNT1-mediated uptake was determined by assessing uptake in PfNT1-injected oocytes and subtracting uptake by water-injected oocytes. Each data point represents nucleoside or nucleotide uptake by at least 10 PfNT1- and 10 water-injected oocytes derived from at least two separate oocyte isolations. B, 60-min uptake of either [3H]adenosine or [3H]AMP by PfNT1-injected oocytes (gray bars), PfNT1-injected oocytes treated with α,β-MeADP (hashed bars), or water-injected oocytes (white bars).

DISCUSSION

Inhibition of Purine Salvage as an Antimalarial Approach—Human blood contains low micromolar concentrations of adenosine and hypoxanthine (35), the preferred purine precursors for P. falciparum. Purines must be added to culture media for robust parasite growth in vitro. Removal of exogenous purines and/or the presence of xanthine oxidase to remove hypoxanthine stops parasite growth in culture (36). Blocking both human and Plasmodium PNP with DADMe-ImmG in the absence of exogenous purines killed cultured parasites, but ADA inhibition with coformycin and AK inhibition with ITU at a 1:1 molar ratio did not augment the effect of PNP inhibition. Thus, PNP is a more sensitive target than ADA. DADMe-ImmG inhibits both host and parasite PNPs, and its dissociation constants for these enzymes is 7 and 890 pm, respectively (37).

Adenosine as a Purine Source for Parasite Growth—Adenosine is the dominant purine nucleoside of human blood (35) and is known to be rapidly transported into the malaria parasite (20, 21, 30, 38, 39). The metabolic evidence shown here indicates that adenosine is converted through PfADA into inosine in P. falciparum. In contrast, in erythrocytes, adenosine is mainly phosphorylated to AMP because of the presence of high affinity adenosine kinase activity (40, 41), and AMP is then rapidly phosphorylated to ATP. Treatment of RBCs with ADA and PNP inhibitors confirmed this pattern and caused a modest increase in erythrocyte cytoplasmic AMP and ATP synthesis from [2-3H]adenosine (Fig. 4A, gray versus black bars). Similar results have been reported in erythrocytes treated with coformycin alone (42).

Adenosine Rescue of Parasite Growth in ADA- and PNP-inhibited Infected Erythrocytes—Earlier work hypothesized that the block of both human and P. falciparum ADAs and PNPs in P. falciparum cultures could not be bypassed by addition of adenosine to the culture media (43). Present results demonstrated that in the presence of ADA and PNP inhibitors P. falciparum were able to grow in the presence of relatively high adenosine concentrations (Fig. 2). Addition of an AK inhibitor (ITU) caused a surprising reduction in parasite growth because P. falciparum have no AK activity. These findings are now explained by uptake of erythrocyte AMP by the parasites.

Although there is no AK gene annotated in the P. falciparum genome (PlasmoDB), the presence of low levels of AK activity was reported previously in a parasite cytoplasmic lysate (6). We also attempted to identify a possible Plasmodium AK gene using an exhaustive bioinformatics search based on hidden Markov models and PSI-BLAST analyses. We identified one potential candidate for P. falciparum AK (PlasmoDB accession number PF11_0453) and expressed the candidate in Escherichia coli, but it had no detectable AK activity (data not shown). Metabolic labeling of purified parasites with [1′-3H]adenosine in the presence of ADA and PNP inhibitors showed complete inhibition of adenosine metabolism corroborating the absence of AK activity in P. falciparum (Fig. 3B).

AMP Metabolism—All results shown here lead us to conclude that P. falciparum can use AMP synthesized in the erythrocyte cytoplasm as a purine source when both human and Plasmodium ADA and PNP are inhibited. The metabolic profiles of [2-3H]adenosine, [2-3H]AMP, and [5′-33P]AMP demonstrated that AMP is transported by the parasite and incorporated into purine pools. Coformycin and DADMe-ImmG treatment in parasites caused complete inhibition of [2-3H]adenosine metabolism, confirming the essential roles of PfADA and PfPNP in adenosine salvage in P. falciparum (Fig. 5A). However, these inhibitors did not inhibit conversion of [2-3H]AMP into the purine pool in P. falciparum, including hypoxanthine (Fig. 5B). The appearance of labeled hypoxanthine (Hx) from [2-3H]AMP is explained by the action of PfAMPDA (AMP + H2O → IMP + NH3) and the reverse reaction of PfHGXPRT (IMP + PRPP ↔ Hx + PPi) (Fig. 1). Metabolic profiles obtained with [2-3H]AMP were confirmed using [5′-33P]AMP as metabolic precursor. Indeed, [5′-33P]AMP was transported by erythrocyte-free P. falciparum and metabolized mainly to ATP, GDP, and IMP (+GMP) (Fig. 6B). ADA and PNP inhibitors had no effect on AMP metabolism, establishing a pathway independent of these steps and confirming that uptake and metabolism of AMP is via the phosphorylated intermediate.

The Possibility of [33P]Pi Cycling from [5′-33P]AMP—P. falciparum has an inorganic phosphate transporter (25), and hydrolysis of [5′-33P]AMP may occur at 37 °C as observed in supernatants from isolated parasites incubated with [5′-33P]AMP (Fig. 6A). The use of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solution prevented [33P]Pi uptake, and treatment with DADMe-ImmG prevented incorporation into purine nucleotides through PfPNP action (Fig. 6D).

AMP Uptake—Anionic, phosphorylated metabolites are assumed to be resistant to transport across the plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells. However, the utilization of [3H]AMP by Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma congolense has been suggested (44), but the possibility of dephosphorylation prior to transport by a trypanosomal 5′-nucleotidase could not be excluded. A Leishmania donovani nucleoside transporter, NT1.1, expressed in Xenopus oocytes was reported to be capable of transporting AMP (45), but no direct AMP uptake was demonstrated. The reported AMP transport by Leishmania NT1.1 may have been due to AMP conversion to adenosine by the Xenopus oocyte ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity, as demonstrated in the current work, followed by uptake of adenosine by NT1.1.

Because the L. donovani nucleoside transporter (NT1.1) was reported to transport AMP (45), we decided to test whether AMP was transported by PfNT1, the orthologous P. falciparum nucleoside transporter. We show that PfNT1 does not transport AMP. Therefore, another transporter/protein is responsible for AMP uptake by the parasites. The P. falciparum genome contains more than 100 putative membrane transport proteins whose function and substrates are unknown. None of the known P. falciparum transporters act on AMP (8, 28). P. falciparum does have a mitochondrial ADP/ATP exchange transporter, the adenylate translocase (PfAdT), but it does not transport AMP (46). Thus, the transporter that mediates AMP uptake remains unknown.

Because the ATP concentration in the RBC cytoplasm is about 2 mm, the possibility that ADP/ATP exchange across the parasite plasma membrane could serve as an energy source for parasite growth has been investigated by two groups (26, 27). Both groups used atractyloside, a known inhibitor of the mitochondrial nucleotide exchanger, to distinguish between nucleoside and nucleotide transport, but they arrived at opposite conclusions. Whether the observed effects were due to inhibition of mitochondria ADP/ATP transport or were due to effects on purine metabolism unresolved. Thus, data supporting the existence of a Plasmodium plasma membrane ADP/ATP transporter remain ambiguous, and no potential candidate genes have been identified through bioinformatics analyses of the Plasmodium genome on which to perform heterologous expression and transport studies.

hAK and PfAMPDA as Drug Targets—P. falciparum is capable of salvaging AMP from the erythrocyte cytosol as an alternative purine source. PfAMPDA and adenylate kinase (AMP + ATP ↔ 2 ADP) compete for conversion of AMP to IMP or ADP for entry to the purine nucleotide pools. AMP uptake by isolated parasites causes larger elevations of IMP and hypoxanthine than does ADP or ATP, indicating that PfAMPDA dominates this pathway, followed by IMP conversion to adenylates. Our studies demonstrated that adenosine rescue of parasite growth occurs via an AMP salvage pathway where PfAMPDA and hAK perform critical roles. This suggests that they might serve as secondary potential drug targets for inhibition of purine salvage required for P. falciparum growth.

Human AK inhibitors have been explored because adenosine is an endogenous neuromodulator with anticonvulsant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties. Thus, hAK inhibitors are potential antiseizure agents associated with elevated extracellular adenosine (47, 48). Several tubercidin-based AK inhibitors, including the ribo- and lyxo-furanosyltubercidin analogues have been described (49). However, because PNP inhibitors alone induce purineless death in cultured P. falciparum, PNP is a primary drug target whereas hAK and PfAMPDA remain as secondary targets, operating under special circumstances of elevated adenosine and erythrocytic AMP.

Conclusions—P. falciparum has no detectable adenosine kinase activity. However, adenosine can rescue the parasite from a purine salvage block by its conversion to AMP in the host and uptake/transport of AMP into the parasite. This finding provides incentive to characterize the remaining transporters in P. falciparum and provides new insights into the purine economy of malaria parasites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Lei Li, Emmanuel Burgos, and Jemy Gutierrez for helpful discussions and technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI49512. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PfNT1, P. falciparum nucleoside transporter 1; AK, adenosine kinase; PRPP, 1-phosphoribosyl-5-pyrophosphate; PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; ADA, adenosine deaminase; PfHGXPRT, P. falciparum hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; DADMe-ImmG, 4′-deaza-1′-aza-2′-deoxy-1′-(9-methylene)-immucillin-G; ITU, iodotubercidin; RBC, red blood cell; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; cpm, counts/min; Pf, P. falciparum; h, human; Imm, immucillin; DPBS, Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline; α,β-MeADP, α,β-methylene ADP; PfAMPDA, P. falciparum AMP deaminase.

M. B. Cassera and V. L. Schramm, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Snow, R. W., Guerra, C. A., Noor, A. M., Myint, H. Y., and Hay, S. I. (2005) Nature 434 214-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyde, J. E. (2005) Trends Parasitol. 21 494-498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyde, J. E. (2007) FEBS J. 274 4688-4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Koning, H. P., Bridges, D. J., and Burchmore, R. J. S. (2005) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29 987-1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyde, J. E. (2007) Curr. Drug Targets 8 31-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyes, P., Rathod, P. K., Sanchez, D. J., Mrema, J. E., Rieckmann, K. H., and Heidrich, H. G. (1982) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 5 275-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi, W., Ting, L. M., Kicska, G. A., Lewandowicz, A., Tyler, P. C., Evans, G. B., Furneaux, R. H., Kim, K., Almo, S. C., and Schramm, V. L. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 18103-18106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner, M. J., Hall, N., Fung, E., White, O., Berriman, M., Hyman, R. W., Carlton, J. M., Pain, A., Nelson, K. E., Bowman, S., Paulsen, I. T., James, K., Eisen, J. A., Rutherford, K., Salzberg, S. L., Craig, A., Kyes, S., Chan, M. S., Nene, V., Shallom, S. J., Suh, B., Peterson, J., Angiuoli, S., Pertea, M., Allen, J., Selengut, J., Haft, D., Mather, M. W., Vaidya, A. B., Martin, D. M., Fairlamb, A. H., Fraunholz, M. J., Roos, D. S., Ralph, S. A., McFadden, G. I., Cummings, L. M., Subramanian, G. M., Mungall, C., Venter, J. C., Carucci, D. J., Hoffman, S. L., Newbold, C., Davis, R. W., Fraser, C. M., and Barrell, B. (2002) Nature 419 498-511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kicska, G. A., Tyler, P. C., Evans, G. B., Furneaux, R. H., Schramm, V. L., and Kim, K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 3226-3231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyler, P. C., Taylor, E. A., Frohlich, R. F., and Schramm, V. L. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 6872-6879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster, H. K., Wiesmann, W. P., and Pavia, C. S. (1984) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 165 225-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trager, W., and Jensen, J. B. (1976) Science 193 673-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura, E. A., Couto, A. S., Peres, V. J., Casal, O. L., and Katzin, A. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 14452-14461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambros, C., and Vanderberg, J. P. (1979) J. Parasitol. 65 418-420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desjardins, R. E., Canfield, C. J., Haynes, J. D., and Chulay, J. D. (1979) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16 710-718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quashie, N. B., de Koning, H. P., and Ranford-Cartwright, L. C. (2006) Malar. J. 5 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo, M., Singh, V., Taylor, E. A., and Schramm, V. L. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 8008-8017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo, M., and Schramm, V. L. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 2649-2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen, R. J., and Kirk, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 11264-11272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter, N. S., Ben Mamoun, C., Liu, W., Silva, E. O., Landfear, S. M., Goldberg, D. E., and Ullman, B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 10683-10691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker, M. D., Hyde, R. J., Yao, S. Y., McRobert, L., Cass, C. E., Young, J. D., McConkey, G. A., and Baldwin, S. A. (2000) Biochem. J. 349 67-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jespersen, T., Grunnet, M., Angelo, K., Klaerke, D. A., and Olesen, S. P. (2002) BioTechniques 32 536-538, 540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen, M., and Akabas, M. H. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 4492-4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmonds, H. A., Fairbanks, L. D., Duley, J. A., and Morris, G. S. (1989) Biosci. Rep. 9 75-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saliba, K. J., Martin, R. E., Broer, A., Henry, R. I., McCarthy, C. S., Downie, M. J., Allen, R. J., Mullin, K. A., McFadden, G. I., Broer, S., and Kirk, K. (2006) Nature 443 582-585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi, I., and Mikkelsen, R. B. (1990) Exp. Parasitol. 71 452-462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanaani, J., and Ginsburg, H. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 3194-3199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin, R. E., Henry, R. I., Abbey, J. L., Clements, J. D., and Kirk, K. (2005) Genome Biol. 6 R26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rager, N., Mamoun, C. B., Carter, N. S., Goldberg, D. E., and Ullman, B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 41095-41099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Downie, M. J., Saliba, K. J., Howitt, S. M., Broer, S., and Kirk, K. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 60 738-748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downie, M. J., Saliba, K. J., Broer, S., Howitt, S. M., and Kirk, K. (2008) Int. J. Parasitol. 38 203-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuoka, I., Ohkubo, S., Kimura, J., and Uezono, Y. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61 606-613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziganshin, A. U., Ziganshina, L. E., King, B. E., and Burnstock, G. (1995) Pfluegers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 429 412-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruns, R. F. (1980) Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 315 5-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traut, T. W. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140 1-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berman, P. A., Human, L., and Freese, J. A. (1991) J. Clin. Investig. 88 1848-1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewandowicz, A., Tyler, P. C., Evans, G. B., Furneaux, R. H., and Schramm, V. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 31465-31468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El Bissati, K., Zufferey, R., Witola, W. H., Carter, N. S., Ullman, B., and Ben Mamoun, C. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 9286-9291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quashie, N. B., Dorin-Semblat, D., Bray, P. G., Biagini, G. A., Doerig, C., Ranford-Cartwright, L. C., and De Koning, H. P. (2008) Biochem. J. 411 287-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beutler, E., Carson, D., Dannawi, H., Forman, L., Kuhl, W., West, C., and Westwood, B. (1983) J. Clin. Investig. 72 648-655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohrenweiser, H. W., Fielek, S., and Wurzinger, K. H. (1981) Am. J. Hematol. 11 125-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komarova, S. V., Mosharov, E. V., Vitvitsky, V. M., and Ataullakhanov, F. I. (1999) Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 25 170-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ting, L. M., Shi, W., Lewandowicz, A., Singh, V., Mwakingwe, A., Birck, M. R., Ringia, E. A., Bench, G., Madrid, D. C., Tyler, P. C., Evans, G. B., Furneaux, R. H., Schramm, V. L., and Kim, K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 9547-9554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez, G., Knight, S., and Strickler, J. (1976) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 53 419-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein, A., Vaseduvan, G., Carter, N. S., Ullman, B., Landfear, S. M., and Kavanaugh, M. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 35127-35134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Razakantoanina, V., Florent, I., and Jaureguiberry, G. (2008) Exp. Parasitol. 118 181-187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boison, D. (2008) Prog. Neurobiol. 84 249-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boison, D. (2008) Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8 2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGaraughty, S., Cowart, M., Jarvis, M. F., and Berman, R. F. (2005) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 5 43-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]