Abstract

Study objective

To examine associations between abuse (physical, sexual, and emotional) in childhood and adolescence/adulthood and sexual activity and dysfunction (FSD) in women.

Design

We analyzed data from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, a community-based epidemiologic study of urologic and sexual symptoms and risk factors in a racially/ethnically diverse random sample of women aged 30–79 (N=3,205 women).

Setting

Boston Area community

Patients

Participants were community residents.

Interventions

Data were observational; no interventions were made.

Main outcome measure

Sexual activity and dysfunction rates (FSD) were assessed by means of a validated questionnaire: the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).

Results

Abuse history was not significantly associated with likelihood of sexual activity. Among those who were sexually active with a partner, a history of each of three types of abuse approximately doubles the risk of FSD. Specifically, childhood emotional (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.28, 3.56), adult sexual (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.23, 3.08), and adult emotional abuse (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.15, 3.01) were all significantly and positively associated with sexual dysfunction (p < .05) after adjusting for covariates (including depression). Analyses of the six FSD domains showed that the relationships were strongest for pain (p = .006) and satisfaction (p < .001).

Conclusions

These findings extend previous literature by identifying an association between FSD and multiple types of abuse, even after adjusting for depression.

Keywords: female sexual dysfunction (FSD), sexual problems, sexual activity, abuse, social epidemiology

Introduction

Findings from epidemiological and clinical studies have identified not only a high prevalence of abuse in women, but also a wide range of diffuse sequelae. National probability and community-based samples conservatively estimate that well over one quarter of the United States (US) adult population has reported either physical or sexual lifetime abuse (1–4). For example, while the likelihood of intimate partner violence increases among women over the lifecourse (3), physical abuse appears more common among men (3) and sexual abuse is more common among women (5,6). Medically, abuse has been strongly associated with a range of gastroenterological and genitourinary symptoms(7–15), pain(16), and worse daily functioning due to poor health (17). Abuse has also been associated with a range of mental health outcomes, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder(18–28) as well as substance abuse(29).

In parallel with these studies of the consequences of abuse, additional literature has considered the numerous antecedents of sexual function problems in women (FSD). Across a range of these studies, correlates related to mental health and well-being (mental health, depression) have been associated with FSD, although in varying ways across race/ethnic groups (30–34). A widely cited study of FSD prevalence by Laumann, Paik and Rosen, which was based on a study of sexual behavior in the US, found that 43% of women reported persistent difficulties in sexual desire or performance(35).

Less is known, however, about the direct association between abuse and sexual functioning, and previous research has produced mixed and often conflicting results. Clinically, it has been observed that victims of abuse show a range of effects, including some victims showing increased sexual interest and others become hypersexual. However, some epidemiological studies have shown that women who have been abused in the past are at increased risk of sexual arousal difficulties or other sexual problems (36–38). Furthermore, results have varied regarding the question of the degree to which depression influences the relationship between abuse and sexual function. For example, while Rellini and Meston (38)found that women with a history of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to be depressed than a non-abused comparison group, Meston et al (37)found that depression had varied effects on sexual self-schemas among women with abuse histories; while depression was significant in predicting a romantic dimension of sexual self-schema, it was not significant in predicting other dimensions.

We aimed to contribute new information to this literature by measuring how several types of abuse might be related to sexual problems or dysfunction in women, adjusting for a series of covariates. We used data from a large (N=5,506), representative, community based sample of adults, ages 30–79, to estimate associations between abuse (physical, sexual or emotional, during childhood or adolescence/adulthood, and any abuse at all) and: (1) the likelihood of having engaged in sexual activity with a partner in the previous four weeks; (2) the reasons for sexual inactivity; (3) prevalence of FSD; and (4) scores for six domains that are often used to obtain an overall assessment of FSD.

Materials and Methods

Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) study is a population-based, random sample epidemiological survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms. Approximately equal numbers of subjects in each of 24 design cells, defined by age (30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–79 years), gender, and race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic and White) were recruited. From April 2002 through June 2005, 2,301 men and 3,205 women were surveyed, including 1,770 Blacks, 1,877 Hispanics, and 1,859 Whites. Additional details of the methodology have been published previously (39). In order for analyses to be representative of the city of Boston, it was necessary to weight observations inversely proportional to their probability of selection into the study(40,41). Weights were further post-stratified to the population of Boston according to the 2000 Census.

Sociodemographic data and information regarding sexual functioning and abuse were obtained during a two-hour, in-person interview, generally in the subject’s home (42). Interview instruments were translated and back-translated in Spanish to ensure cross-cultural accuracy of meaning; 26% of the interviews were conducted in Spanish. All respondents completed informed consents and IRB approval for the data collection was obtained through review by the IRB at New England Research Institutes. One author has a conflict of interest regarding consulting work.

Measurement of Abuse

We measured abuse with a self-administered questionnaire from a clinically validated abuse instrument developed by Leserman et al(43). Sexual abuse was defined as present if respondents answered in the affirmative to any of the following (a-f for childhood ≤13 years; b-f for adulthood ≥14 years): Has another adult ever (a) Exposed the sex organs of their body to you when you did not want it? (b) Threatened to have sex with you when you did not want this? (c) Touched the sex organs of your body when you did not want this? (d) Made you touch the sex organs of their body when you did not want this? (e) Forced you to have sex when you did not want this? (f) Have you had any other unwanted sexual experiences not mentioned above? Physical abuse (child or adult) was defined as present if a respondent indicated that an adult had “occasionally” or “often” “hit, kick, or beat” them, or had “seldom,” “occasionally,” or “often” “seriously threatened your life.” Emotional abuse was defined as present if a respondent indicated that an adult “emotionally abused, humiliated, or insulted you” “occasionally” or “often.” The prevalence of abuse in BACH ranged from 17% for childhood emotional abuse to 26% for childhood sexual abuse, and these estimates are comparable with findings from other community-based studies(44). In the context of this literature, a key strength of BACH is the ability to measure all six types of abuse in one dataset, as most data on this topic has tended to focus on either one life stage or type of abuse.

Measurement of Female Sexual Functioning

Female sexual functioning was measured using an abbreviated version of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)(45,46), and for present purposes we refer to this instrument as the BACH FSFI questionnaire. Due to time constraints (BACH participation required a 2+ hour time commitment on the part of participants), a 10-item BACH FSFI was adapted from the original 19-item FSFI, including questions that measured all six dimensions of sexual functioning addressed in the original FSFI: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain and satisfaction. While all respondents were asked about their levels of sexual desire, only those who reported sexual activity with a partner in the last month were asked to answer the remaining questions. In addition to being a validated measurement, this abbreviated form of the FSFI offered a multidimensional assessment of sexual functioning that also permitted comparisons that have been limited in other studies where questions were worded too differently to allow for comparison of results (30,45,47). The FSD prevalence rate in BACH was 34%(48), which compared favorably with previous studies of sexual functioning (35).

Scoring of the BACH FSFI followed the convention of the original FSFI, which multiplies the sum of the items in each domain by a domain factor, the total score being equal to the sum of the domain scores. For the BACH FSFI, domain scores derived from one item (arousal and lubrication) were multiplied by 1.2, domain scores derived from 2 items (desire) were multiplied by 0.6, and domain scores derived from three items (orgasm and pain) were multiplied by 0.4. As a result, BACH FSFI domain scores could range from 0 to 6.0 (except desire, which could range from 1.2 to 6.0) and the BACH FSFI total score could range from 1.2 to 36.0 (the mean was 27.7 with a standard deviation of 5.4). This scoring method allowed for direct comparison between the BACH FSFI domain scores and the original FSFI domain scores.

The BACH FSFI was validated against the same dataset used to validate and develop cut-off scores for the original FSFI(46). This sample consisted of 568 women, of whom 261 had no sexual dysfunction and 307 had one or more sexual dysfunctions, as determined by clinical interview. The BACH FSFI total score was found to correlate highly with the FSFI total score in the original sample (Pearson r = .979, p < .001) and have high internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .917). The original FSFI instrument has been additionally validated using empirically derived cutoff scores and normative data from different samples(49–51). For the original FSFI, a cutoff score of 26.5 was determined based on a sensitivity score of .801 and a specificity score of .851(46), and scores equal to or below the cut-off score are used to indicate presence of sexual dysfunction. A cut-off score of 26.2 was determined for the BACH FSFI, based on the same sensitivity and specificity scores, with an area under the ROC curve of .888. Thus, for the present study, women with a score of 26.2 or less on the BACH FSFI were classified as having sexual problems.

Other Covariates

We also examined a series of potential confounding variables, including: (1) sociodemographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status [married/living with a partner, divorced/separated/widowed, single/other], employment status, and socioeconomic status [SES][a categorical variable based on a combination of education and income, following from Green (52)]); (2) anthropometrics (body mass index (kg/m2); (3) physical health (physical health status (as measured by the SF-12(53)), diabetes, heart conditions, vascular conditions, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, arthritis, and sexually transmitted diseases); (4) mental health (depressive symptoms as measured by a short form CES-D (54)); and (5) lifestyle factors (alcohol use, smoking, and physical activity (as measured by the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) (55)).

Statistical Analyses

To consider whether women who had been abused were less likely to engage in sexual activity relative to their non-abused counterparts, chi-square tests were used to compare the percent sexually active in BACH by abuse status (for each of the six types). A multivariable logistic regression model for the probability of BACH respondents reporting sexual relations with a partner in the previous four weeks was fit to describe differences between sexually active and inactive women from the BACH study.

Next, we considered whether respondents’ reported reasons for sexual inactivity varied by abuse status. Respondents were able to select from five reasons and could indicate more than one reason as applicable: lack of a partner; lack of interest in sex; pelvic or vaginal pain or urinary problem interfering with sex; another health problem interfering; or partner has a health problem that interferes. Chi-square tests were used to compare the percent reporting sexual inactivity for each reason by abuse status (for each of the six types of abuse).

To examine the relationship between abuse and sexual functioning among the sexually active women in BACH and to understand the effect of depression on this relationship, we used multivariable logistic regression modeling. To identify which covariates to adjust for, a backwards selection technique was used. Specifically, models were fit until F tests for all covariates remaining had p-values less than 0.05; age and race/ethnicity were kept regardless. After identifying the covariates to adjust for, we fit the following models predicting the odds of FSD: 1) adjusting for covariates but not abuse or depressive symptoms; 2) adjusting for covariates including depressive symptoms but not abuse and 3) adjusting for covariates, depressive symptoms and abuse. To assess the relationship of FSD with abuse by type, separate logistic regression models were fit considering each type of abuse separately (adjusting for the covariates as described above). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to describe the odds of reporting FSD among women who reported abuse (by type of abuse) compared to those who did not were presented.

To examine how the number of types of abuse experiences affects FSD, chi-square tests were conducted to compare the number of types of abuse with FSD prevalence. We compared the average scores for each FSD domain (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain) to assess whether or not abuse had a greater effect on specific domains within the BACH FSFI measure. To ascertain whether the FSD domains were differentially associated with abuse, separate linear regression models were fit for each of the domains adjusting for the covariates mentioned above. Least squares means were presented for each of the FSD domains by abuse status; p-values based on individual t-tests were compared for each of the models to determine which domains were more highly correlated with abuse.

Because a complete case analysis could potentially lead to biased and inefficient estimates, the multiple imputation (MI) procedure in SAS version 9.1 (56) was used to impute missing values (57). All statistical analyses took into account the complex survey design using sampling weights and were done using SUDAAN version 9.0.1 (56–59). Not accounting for multiple comparisons, statistical tests with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Abuse and Sexual Activity

We first considered whether women who had been abused were less likely to engage in sexual activity relative to their non-abused counterparts. Overall, 48.9% of women reporting any abuse were sexually active, compared to 52.9% of the non-abused group (p = 0.19). Regardless of abuse type, women who had been abused were less likely than their non-abused counterparts to report sexual activity in the past four weeks, but none of these differences reached statistical significance. Therefore, we do not expect that abuse systematically affects likelihood of sexual activity among BACH respondents.

In a multivariable logistic regression model not presented here, we found that, on average, relative to their sexually active counterparts, women who were sexually inactive in BACH were more likely to be White or Hispanic (relative to Black); were older; were more likely to be single, divorced, widowed, or separated; had higher BMIs; had higher waist-to-hip ratios; had lower alcohol consumption; had less physical activity; were of lower SES; had lower mental and physical health scores; and were more likely to report depressive symptoms. All six types of abuse were adjusted for in these analyses, and they were all insignificant for the overall population (33).

Reasons for Sexual Inactivity

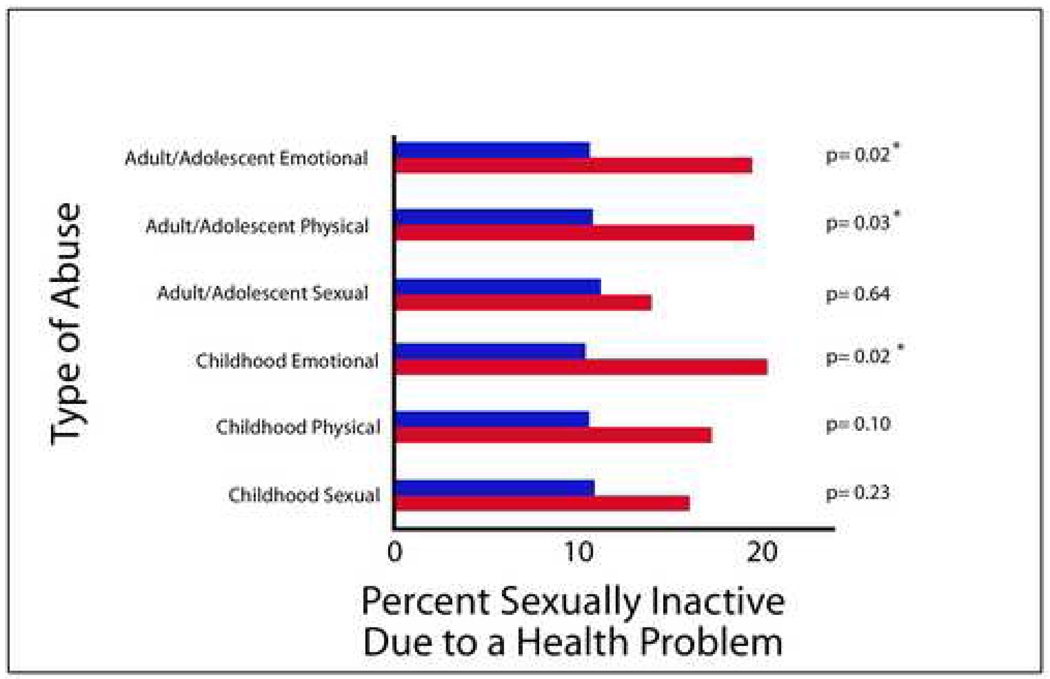

There were no significant differences between the abused and non-abused groups (for any abuse type) in terms of their likelihood of having partners, interest in sex, or pelvic/vaginal pain or urinary problems that might interfere with sexual activity. However, those with childhood emotional, adult physical, or adult emotional abuse were at increased risk for having health problems that interfered with sexual activity (Figure 1). Also, those with childhood sexual abuse were more likely than their non-abused counterparts to have a partner with a health problem that interfered with sexual activity (16.0 vs. 8.6%, p = 0.04), but for all other types of abuse the differences between abuse and non-abused women were not significant. Together, these results indicate that while abused women might have had different reasons for being sexually inactive, their likelihood of engaging in sexual activity and their desire levels are comparable to those of their non-abused counterparts.

Figure 1. Percentage of BACH respondents reporting sexual inactivity due to a health problem that interferes.

Red (abuse population)

Blue (non-abused population)

Abuse and Female Sexual Dysfunction

Even after adjusting for depression, abuse is associated with an approximate two-fold increase in the odds of FSD (odds ratio: 1.86, 95% CI 1.21, 2.85, p = 0.005) (Table 1). When considering the relationships with FSD by type of abuse, childhood emotional abuse (odds ratio 2.13; 95%CI 1.28, 3.56; p=0.004), adolescent/adult sexual abuse (odds ratio 1.94; 95%CI 1.23, 3.08; p=0.005), and adolescent/adult emotional abuse (odds ratio 1.86, 95%CI 1.15, 3.01; p=0.011) are all positively associated with FSD (Table 2). Because depression has been frequently cited in the literature as a significant correlate and consequence of abuse, we note that the association we observed between the three types of abuse and FSD is not accounted for, when we adjust for the effects of depression.

Table 1.

Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) from separate logistic regression models predicting odds of FSD considering overall abuse and depressive symptoms controlling for covariates

| Model 1: considering only covariates |

Model 2: considering depressive symptoms only with no overall abuse, adjusting for covariates |

Model 3: considering depressive symptoms and overall abuse, adjusting for covariates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

F test p-value |

OR (95% CI) |

F test p-value |

OR (95% CI) |

F test p-value |

|

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 30–39 |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

|||

| 40–49 | 1.17 (0.71,1.93) |

1.20 (0.72,2.00) |

1.17 (0.71,1.92) |

|||

| 50–59 | 2.61 (1.57,4.36) |

2.78 (1.66,4.67) |

2.82 (1.68,4.73) |

|||

| 60–79 | 3.40 (1.99,5.82) |

3.63 (2.08,6.34) |

3.83 (2.18,6.72) |

|||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Black | 0.52 (0.32,0.82) |

0.43 (0.27,0.69) |

0.44 (0.28,0.71) |

|||

| Hispanic | 0.59 (0.37,0.95) |

0.44 (0.27,0.73) |

0.47 (0.29,0.78) |

|||

| White |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

|||

| Marital status | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.009 | |||

| Married |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

|||

| Sep/divorced/widowed | 0.43 (0.23,0.82) |

0.38 (0.19,0.73) |

0.33 (0.16,0.67) |

|||

| Single | 0.91 (0.56,1.48) |

0.78 (0.47,1.28) |

0.75 (0.46,1.23) |

|||

| Alcohol | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.024 | |||

| None |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

1 Reference |

|||

| <1 drink/day | 0.53 (0.36,0.77) |

0.58 (0.39,0.87) |

0.58 (0.39,0.86) |

|||

| 1+ drink/day | 0.71 (0.41,1.21) |

0.78 (0.45,1.36) |

0.75 (0.43,1.30) |

|||

| Depressive symptoms | 3.13 (1.93,5.09) |

<0.001 | 2.78 (1.71,4.52) |

<0.001 | ||

| Any abuse | 1.86 (1.21,2.85) |

0.005 | ||||

F tests of the overall effects of each covariate were tested; p-values were <0.05 in all cases.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models predicting prevalence of FSD (Including one type of abuse in each model and controlling for the same covariates as in Table 1: age, race/ethnicity, marital status, daily alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms).

| Type of Abuse | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood sexual | 1.47 | 0.93, 2.32 | 0.10 |

| Childhood physical | 1.54 | 0.94, 2.52 | 0.085 |

| Childhood emotional | 2.13 | 1.28, 3.56 | 0.004 |

| Adulthood sexual | 1.94 | 1.23, 3.08 | 0.005 |

| Adulthood physical | 1.23 | 0.73, 2.08 | 0.43 |

| Adulthood emotional | 1.86 | 1.15, 3.01 | 0.011 |

We also evaluated how women who experienced more types of abuse were affected sexually. In particular, we found that the prevalence of FSD increased for women who reported one type of abuse (relative to none) and again for those reporting two or more types of abuse. This association held for those women who had any abuse, those with childhood abuse only, and for those with adult/adolescent abuse only. For example, while only 28.2% of non-abused women reported FSD symptoms, the prevalence climbed to 44.9% for those who reported two or more types of abuse (p = .006).

Variation by FSD domains

Of the six FSD domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain), the pain and satisfaction domains were most closely associated with abuse histories (Table 3). These results were similar by type of abuse. Because BACH FSFI questions pertaining to pain asked whether it occurred in conjunction with vaginal penetration, we also conducted additional analyses to ascertain whether women with abuse histories were less likely to attempt vaginal penetration than their non-abused counterparts, and we observed no significant differences.

Table 3.

Average FSD Domain Scores by abuse status

| Domain | Any Abuse | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Y | N | p | |

| Desire | 3.58 | 3.71 | 0.26 |

| Arousal | 4.32 | 4.50 | 0.14 |

| Lubrication | 5.14 | 5.32 | 0.072 |

| Orgasm | 4.62 | 4.81 | 0.077 |

| Satisfaction | 4.28 | 4.78 | <0.001 |

| Pain | 4.96 | 5.38 | 0.006 |

Discussion

We used the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey to examine associations between a history of abuse and the likelihood of engaging in sexual activity, reasons for sexual inactivity, and prevalence of sexual dysfunction (overall and by sub-domains) among women in a diverse community-based sample. While the reasons that respondents reported for being sexually inactive varied by abuse status, with abused women more likely to report health problems (their own and partners’) that interfered with sex, abuse status did not predict the likelihood of sexual activity. Among sexually active respondents, we found that women with histories of childhood emotional abuse, adolescent/adult sexual abuse, and adolescent/adult emotional abuse were at increased risk for problems with sexual functioning, as measured by the domain scores in the BACH FSFI (arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, pain, and satisfaction). Specifically, the domains of pain and satisfaction were most strongly associated with abuse. We also found that FSD prevalence increased if multiple types of abuse were reported. These findings were consistent even after adjusting for depression.

Epidemiologically, these results underscore the importance of using a community-based sample (rather than patient-based or convenience samples). The population-representative BACH sample allows for analysis of these effects in a group of women that is diverse in age and race/ethnicity. The depth and breadth of psychosocial data available in BACH facilitated a detailed examination of factors that are thought to be associated with abuse and sexual functioning, but are typically limited in detail or non-existent in other studies. Detailed information about abuse and sexual functioning allowed us to investigate more completely the role of specific risk factors and outcomes. To the extent that most studies focus on one type of abuse, the three types and two lifecourse stages represented in the BACH study allowed for unprecedented analyses of the effects of the breadth and magnitude of abuse on sexual function. The wide range of covariates included in our analysis similarly allowed for simultaneous examination of the role of depression, often considered a confounder or mediator that might obscure the abuse-FSD link. Indeed, our results highlight the persistent importance of psychosocial antecedents in understanding FSD.

Clinically, these findings highlight the importance of clinical screening during the medical interview to identify women with abuse histories. Based on our results showing that the likelihood of sexual activity does not vary by abuse status, clinicians should assume that abused and non-abused women are equally likely to be sexually active. However, among those who are sexually active, women with abuse histories are at increased risk for sexual problems, particularly pain or satisfaction problems. In terms of improving sexual functioning for these women, it may be the case that focused intervention on the specific domains associated with abuse will lead to improvement in overall sexual function. Especially among women with low satisfaction, non-invasive, multimodal interventions may be productive for reducing overall sexual problems (and these women may experience limited returns from invasive or pharmaceutical interventions). The case of pain is more ambiguous, since the mechanisms linking abuse and pain are poorly understood and many types of sexual pain symptoms present in women (e.g., dyspareunia, vulvar vestibulitis) have been resistant to treatment. Rather than focusing exclusively on either medical or psychosocial intervention, multimodal approaches may be beneficial. Additionally, it is important for clinicians to consider the possibility that abuse contributing to sexual problems may be occurring presently, rather than something that happened to women when they were children. For example, if a woman’s spouse/partner is emotionally or sexually abusing her as an adult, our result suggests she may be at increased risk for sexual problems. By screening in a medical interview about abuse, physicians may be able to identify concurrent life circumstances that exacerbate sexual problems. Overall, our results suggest that focused attention to the domains in which sexual problems occur and consideration of concurrent abuse risk provide two important opportunities for clinical screening, possible therapeutic intervention (pharmaceutical or psychosocial) and patient counseling.

The BACH sample incorporated nearly equal numbers of the three major racial/ethnic groups in Boston, but was unable to include other racial/ethnic groups throughout the US (e.g., Asian Americans). The BACH sample was compared to three different government-sponsored national surveys (the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the National Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Survey (BRFSS)) on many health-related variables. While there are a few differences, most of the BACH estimates are comparable, suggesting that BACH rates (with appropriate adjustments) could be generalizable to the US as a whole. These data are unique in both the breadth of the sample and then range of abuse experiences measured, making a critical contribution toward filling gaps in literature on the effects of abuse and causes of female sexual problems.

Previous studies have documented extensive associations between physical, emotional, and sexual abuse across the life course and a range of diffuse health consequences, especially those related to pelvic pain, gastroenterological, and mental health symptoms. At the same time, many of the precise causes of female sexual problems are poorly understood and broadly attributed to psychosocial problems such as depression. The results presented here extend previous work by: (1) simultaneously examining abuse, FSD, and important covariates such as depression; (2) simultaneously considering the effects of several types of abuse at multiple life stages, not only childhood sexual abuse; (3) examining how abuse and female sexual functioning are associated in a diverse, community-based sample that includes multiple racial/ethnic groups as well as a wide range of age groups; and (4) assessing the differential effects of abuse on separate domains of sexual function, which helps focus interventions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Markus Wiegel for his assistance with the BACH FSFI.

This study was supported by NIH grant #DK56842.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Capsule:

In a representative, community-based random survey sample, we found that a history of childhood emotional, adult sexual, or adult emotional abuse increased the likelihood of suffering symptoms of Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD).

References

- 1.Scher CD, Forde DR, McQuaid JR, Stein MB. Prevalence and demographic correlates of childhood maltreatment in an adult community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis J, Smith T, Marsden P. General Social Surveys, 1972–2002, 2nd ICPSR Version. Ann Arbor, MI: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Fact Sheets. 2002 http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/en/index.html.

- 5.Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis I, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult ment and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davila GW, Bernier F, Franco J, Kopka SL. Bladder dysfunction in sexual abuse survivors. J Urol. 2003;170:476–479. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000070439.49457.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulme PA, Grove SK. Symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15:519–532. doi: 10.3109/01612849409006926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klevan JL, De Jong AR. Urinary tract symptoms and urinary tract infection following sexual abuse. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:242–244. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150260122044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reinhart MA, Adelman R. Urinary symptoms in child sexual abuse. Pediatr Nephrol. 1989;3:381–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00850210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellsworth PI, Merguerian PA, Copening ME. Sexual abuse: another causative factor in dysfunctional voiding. J Urol. 1995;153:773–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jundt K, Scheer I, Schiessl B, Pohl K, Haertl K, Peschers UM. Physical and sexual abuse in patients with overactive bladder: is there an association? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leserman J. Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:906–915. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188405.54425.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toomey TC, Hernandez JT, Gittelman DF, Hulka JF. Relationship of sexual and physical abuse to pain and psychological assessment variables in chronic pelvic pain patients. Pain. 1993;53:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90062-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillingim RB, Edwards RR. Is self-reported childhood abuse history associated with pain perception among healthy young women and men? Clin J Pain. 2005;21:387–397. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000149801.46864.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meltzer-Brody S, Leserman J, Zolnoun D, Steege J, Green E, Teich A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:902–908. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258296.35538.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt RL, Montesinos S, Christensen RC. Physical and sexual abuse history in women seeking treatment at a psychiatric clinic for the homeless. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:58–60. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200701000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancaster G, Rollinson L, Hill J. The measurement of a major childhood risk for depression: Comparison of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) 'Parental Care' and the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) 'Parental Neglect'. J Affect Disord. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia SK, Bhatia SC. Childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao FB, Huang K, Kim S, Ye Q, Sun Y, Zhang CY, et al. Correlation between psychopathological symptoms, coping style in adolescent and childhood repeated physical, emotional maltreatment. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2006;44:688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vranceanu AM, Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptoms: The role of social support and stress. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acierno R, Lawyer SR, Rheingold A, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE. Current psychopathology in previously assaulted older adults. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22:250–258. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobb AR, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG, Cann A. Correlates of posttraumatic growth in survivors of intimate partner violence. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:895–903. doi: 10.1002/jts.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Stress Sensitization and Adolescent Depressive Severity as a Function of Childhood Adversity: A Link to Anxiety Disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dervic K, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Protective factors against suicidal behavior in depressed adults reporting childhood abuse. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:971–974. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243764.56192.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Theodore A, English DJ, Black MM, et al. Effect of early childhood adversity on child health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1232–1238. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women's substance abuse: national survey findings. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1023420431760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, Brown C, Mouton C, Reame N. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463–473. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johannes CB, Avis NE. Gender differences in sexual activity among mid-aged adults in Massachusetts. Maturitas. 1997;26:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)01102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutfey KE, Link CL, Rosen RC, Wiegel M, McKinlay JB. Prevalence and Correlates of Female Sexual Activity and Function: Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9290-0. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paik A, Laumann EO. In: Prevalence of Women's Sexual Problems in the USA. Goldstein I, Meston C, Davis S, Traish A, editors. London: Women's Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment; 2005. pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. Jama. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randolph ME, Reddy DM. Sexual abuse and sexual functioning in a chronic pelvic pain sample. J Child Sex Abus. 2006;15:61–78. doi: 10.1300/J070v15n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meston CM, Rellini AH, Heiman JR. Women's history of sexual abuse, their sexuality, and sexual self-schemas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:229–236. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rellini AH, Meston CM. Sexual Desire and Linguistic Analysis: A Comparison of Sexually-Abused and Non-Abused Women. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the Urologic Iceberg: Design and Implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. ed 3d. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: J. Wiley; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKinlay SMKD, Johnson P, Downey K, Carleton RA. Health survey research methods: proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Health Survey Research Methods, Washington, D.C., May 1982. NCHSR research proceedings series. Rockville, MD (5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville 20857): U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health National Center for Health Services Research; 1984. A field approach for obtaining physiological measures in surveys of general populations: Response rates, reliability, and costs; p. 379. vi. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med. 1995;21:141–150. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lutfey KE, Link CL, Litman HJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence and Correlates of Childhood and Adult Physical, Sexual and Emotional Abuse: Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.11-043. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosen RC, Laumann EO. The prevalence of sexual problems in women: how valid are comparisons across studies? Commentary on Bancroft, Loftus, and Long's (2003) 'distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships". Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:209–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1023405415831. discussion 213-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Reply to Rosen and Laumann's (2003) The prevalence of sexual problems in women: How valid are comparisons across studies? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:213–216. doi: 10.1023/a:1023405415831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fitzgerald MP, Link CL, Litman HJ, Travison TG, McKinlay JB. Beyond the lower urinary tract: the association of urologic and sexual symptoms with common illnesses. Eur Urol. 2007;52:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Likes WM, Stegbauer C, Hathaway D, Brown C, Tillmanns T. Use of the female sexual function index in women with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32:255–266. doi: 10.1080/00926230600575348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Kohorn EI, Minkin MJ, Kerns RD. Assessing sexual function and dyspareunia with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with vulvodynia. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:315–324. doi: 10.1080/00926230490463264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sidi H, Puteh SE, Abdullah N, Midin M. The Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction and Potential Risk Factors That May Impair Sexual Function in Malaysian Women. J Sex Med. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT user's guide. Cary, N.C: SAS Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schafer J. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 9.0. Cary, Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]