Abstract

Inflammation is an important vertebrate defense mechanism against ecto-parasites for which ticks have evolved numerous mechanisms of modulation. AM-33 and TSGP4, related lipocalins from the soft ticks Argas monolakensis and Ornithodoros savignyi binds cysteinyl leukotrienes with high affinity as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry. This was confirmed in a smooth muscle bioassay that measured contraction of guinea pig ileum induced by leukotriene C4 where both proteins inhibited contraction effectively. Conservation of this function in two diverse soft tick genera suggest that scavenging of cysteinyl leukotrienes evolved in the ancestral soft tick lineage. In addition soft ticks also evolved mechanisms that target other mediators of inflammation that includes scavenging of histamine, serotonin, leukotriene B4, thromboxane A2, ATP and inhibition of the complement cascade. Inhibitors of blood-coagulation and platelet aggregation were also present in the ancestral soft tick lineage. Because histamine and cysteinyl leukotrienes are mainly produced by mast cells and basophils, and these cells are important in the mediation of tick rejection reactions, these findings indicate an ancient antagonistic relationship between ticks and the immune system. As such, modulation of the hemostatic system as well as inflammation was important adaptive responses in the evolution of a blood-feeding lifestyle in soft ticks.

Keywords: Argas monolakensis, Ornithodoros savignyi, TSGP4, AM-33, vasodilator, leukotrienes, mast cell, basophil

1. Introduction

During feeding ticks cut into the host’s skin using their hypostome and chelicerae in order to create a feeding site (hematoma), where blood pools and from which the tick can engorge. This probing causes tearing of tissues and rupturing of capillary vessels, with the subsequent release of mediators that activate the host’s defense mechanisms. As such, ticks need to modulate their vertebrate host’s immune and hemostatic systems (Ribeiro, 1989). The hemostatic system is composed of blood clotting, platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction. The immune response is composed of innate (inflammation, the complement cascade and pain) and adaptive (B and T cell mediated) responses. These systems interact to form complex and redundant networks. In response, ticks evolved a reciprocal complex salivary gland repertoire of molecules that is secreted into the feeding site that target multiple key components of the host’s defense systems (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003; Mans and Neitz, 2004a).

Edema is one of the characteristics of inflamed tissue and is caused by an increase in vascular permeability that leads to accumulation of fluids, swelling and infiltration of leukocytes in the extra-vascular bed. This leads to occlusion of blood vessels and decreased blood flow. Edematous inflammatory reactions at the tick feeding site are associated with tick rejection and ticks evolved various mechanisms to counteract inflammation (Ribeiro, 1989). Mediators of inflammation, such as histamine or serotonin are for example scavenged by lipocalins in both soft and hard ticks (Paesen et al. 1999; Mans et al. 2008a). In soft ticks, lipocalins that scavenge leukotriene B4 (LTB4), a potent inflammatory mediator, has also been identified (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Targeting of another class of inflammatory mediators, the cysteinyl leukotrienes, by ticks has not yet been characterized. The current study describes soft tick lipocalins that bind cysteinyl leukotrienes with high affinity.

Soft tick lipocalins (TSGP1 through 4) were previously identified as the most abundant proteins in the salivary glands of the soft tick Ornithodoros savignyi (Mans et al. 2001; Mans et al. 2003). TSGP2 and TSGP4 were implicated in sand tampan toxicoses (Mans et al. 2002). Recently, it was shown that TSGP1 act as a scavenger of histamine and serotonin (Mans et al. 2008a). TSGP3 has been shown to inhibit collagen-induced platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction by scavenging of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Both TSGP2 and TSGP3 also inhibit edema by scavenging LTB4 and interact with complement C5 to inhibit the complement cascade (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). No function has yet been elucidated for TSGP4. In the current study we show that TSGP4 and AM-33, a related lipocalin from the tick Argas monolakensis, can bind the cysteinyl leukotrienes, leukotriene C4, D4 and E4 (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4) with high affinity. This finding is novel and indicates that scavenging of mediators of inflammation evolved in the ancestral lineage to soft ticks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Bio-informatical analysis of the TSGP4 clade

The sequence of TSGP4 (Genbank accession: 25991438) were used to identify possible orthologs from the non-redundant Genbank protein sequence database by BLASTP analysis (Altschul et al. 1990). Sequences with E-values less than 10−10 were aligned using ClustalX and the edges trimmed manually to provide a conserved core of sequence alignment (161 informative positions) (Jeanmougin et al. 1998). Using this alignment, neighbor-joining analysis was performed using the Mega2 software (Kumar et al. 2001). Gaps were treated as pairwise deletion, amino acid distance were calculated using Poisson correction and branch support were estimated using bootstrap analysis (10 000 bootstraps). For molecular models the sequences for TSGP4 and AM-33 (Genbank accession: 114152974) were submitted to the PHYRE server (Bennett-Lovsey et al. 2008). Models obtained based on the structure of OMCI (Roversi et al. 2007), were visualized using the Pymol package (DeLano, 2002).

2.2 Recombinant protein expression

A gene for TSGP4 were synthesized (GeneArt) and for AM-33 were obtained from a cDNA library previously synthesized (Mans et al. 2008b). Genes were cloned and recombinantly expressed and analyzed for quality as previously described (Calvo et al. 2006; Mans and Ribeiro, 2008).

2.3 Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed using a VP-ITC calorimeter (Microcal, Northhampton, MA) as described (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Lipid-derived ligands included arachidonic acid (AA), LTB4, LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, U46619, carbocyclic thromboxane A2 (cTXA2), prostaglandin E2 and platelet activating factor (PAF) (Cayman Chemical, MI, USA). All proteins were tested at 2 µM protein and 20 µM ligand unless otherwise indicated.

2.4 Smooth muscle bioassay

Contraction of guinea pig ileum by LTC4 was measured isotonically with a load of 1.5 g. A modified Tyrode solution (with 10 mM HEPES buffer) that was oxygenated by continuous bubbling of air was used in the assays (Webster and Prado, 1970). Ileum preparations were pre-incubated with 300 nM TSGP4 or AM-33. LTC4 were added in 100 nM increments until maximum contraction was reached.

3. Results

3.1 The major functional lipocalin clades found within soft ticks

Previously, four major lipocalins (TSGP1-4) were described from the salivary glands of the soft tick, O. savignyi (Mans et al. 2003). Recent sialome projects on the salivary gland proteins from A. monolakensis and O. parkeri has indicated that most soft tick lipocalins falls roughly into three major classes as defined by the TSGPs (Francischetti et al. 2008; Mans et al. 2008b). TSGP1 and related proteins has been shown to be scavengers of histamine and serotonin (Mans et al. 2008a). TSGP2, TSGP3 and related moubatin-like proteins targets complement C5 and leukotriene B4, while TSGP3 and moubatin can also scavenge thromboxane A2 (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Only TSGP4 has no defined function yet and we thus set out to discover possible functions for TSGP4 and its homologs.

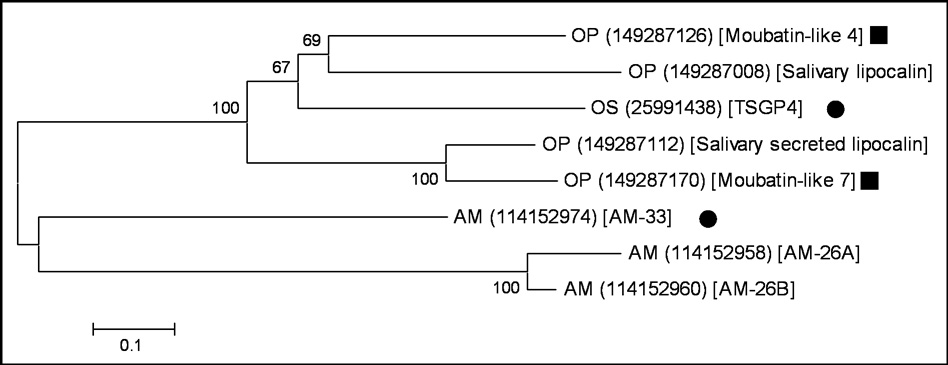

BLASTP analysis of the non-redundant Genbank protein database using the sequence of TSGP4 retrieved 8 soft tick lipocalins with E-values below 10−10. These included lipocalins from the sialomes of A. monolakensis and O. parkeri (Francischetti et al., 2008; Mans et al. 2008). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the proteins grouped into two major clades, one for the genera Ornithodoros and the other for Argas, that each contained a number of genus specific proteins (Fig. 1). This suggested that the clades form an orthologous group (i.e. monophyletic) and that gene duplication events after divergence of the two genera led to a number of paralogous proteins. It should be noted that two of the proteins analyzed were previously annotated as “moubatin-like” (Francischetti et al. 2008). BLASTP analysis of the non-redundant database retrieves TSGP4 as best “other species” hit for both species. As such, their functional relationship to moubatin seems dubious and we infer a closer relationship to TSGP4. Similar annotations are addressed in regard to biogenic amine-binding proteins and their relationship to moubatin as well (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TSGP4-related lipocalins. Lipocalins were retrieved from the non-redundant database by BLASTP analysis of TSGP4. Closely related sequences were selected based on an E-value cut-off less that 10−10. Neighbor-joining analysis was performed, with a Poisson amino acid substitution model and gaps treated as pairwise deletion. Support values were obtained by bootstrap analysis (10000 replicates). Sequences are described by a species designation (AM: A. monolakensis; OP: O. parkeri, OS: O. savignyi), Genbank accession number in round brackets and annotation line in square brackets. Dots indicate proteins characterized in the present study. Squares indicate proteins for which the functional and evolutionary relationship with moubatin is uncertain.

AM-33 was the first Argas derived protein retrieved from the non-redundant protein database by TSGP4 and reciprocal BLASTP analysis against the non-redundant protein database gave as best hit TSGP4. AM-33 is a highly abundant lipocalin found in the salivary glands of A. monolakensis (Mans et al. 2008b). Given the basal position in the phylogenetic tree we considered it possible that it would be the ancestral ortholog of TSGP4. As such, a comparative analysis of AM-33 and TSGP4 were performed in order to derive information that will give an indication as to their function.

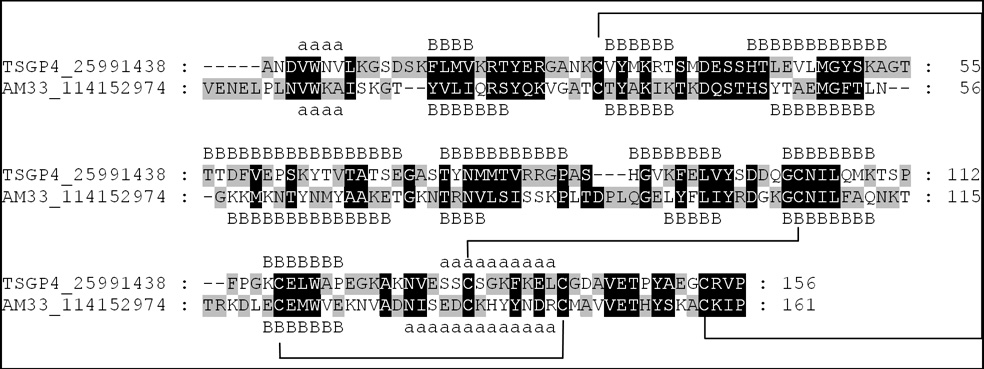

3.2 Alignment of TSGP4 and AM-33

TSGP4 and AM-33 show 23% sequence identity and 50% sequence similarity based on the PAM250 matrix (DN, EQ, ST, KR, FYW, LIVM) (Fig. 2). Conserved residues occur in discrete clusters along the sequence and correspond with regions predicted to be involved in secondary structure formation. Each possess six cysteine residues that are conserved and correspond to the previously proposed unique disulphide bond pattern for TSGP4 (Mans et al. 2003). This cysteine arrangement is found in all members of the TSGP4/AM-33 clade (results not shown) and differs from that of the other soft tick lipocalin clades, notably the histamine and serotonin-binding and the moubatin clades (Mans et al. 2003; Mans et al. 2008a; Mans and Ribeiro, 2008).

Fig. 2.

Alignment of TSGP4 and AM-33. Residues shaded in black indicate similarity based on the PAM250 matrix. Disulphide bonds are indicated as predicted previously for TSGP4 (Mans et al. 2003). Secondary structures (a: α-helices; B: β-strands) were obtained from structure models obtained from the PHYRE server based on the structure of OMCI (Bennet-Lovley et al. 2008; Roversi et al. 2007).

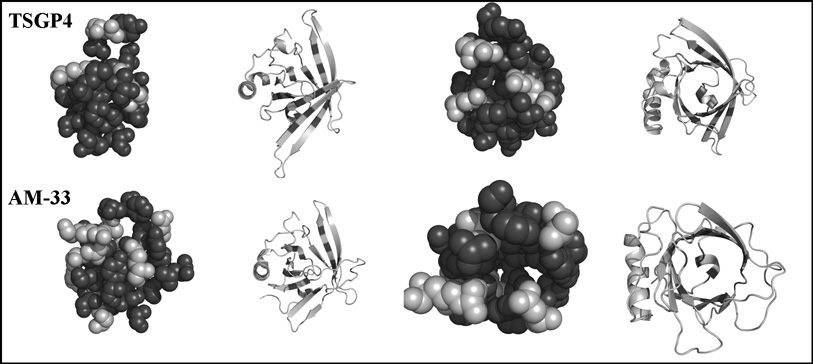

3.3 Molecular modeling of TSGP4 and AM33

TSGP4 and AM-33 were submitted to the PHYRE server (Bennett-Lovsey et al. 2008), and for both models were obtained based on the structures of the histamine-binding protein (FS-HBP2) from Rhipicephalus appendiculatus (E-14, E-15) and OMCI, the complement inhibitor from O. moubata (E-6, E-7), respectively (Paesen et al. 1999; Roversi et al. 2007). The estimated precision for each model were 100% and confirmed that TSGP4 and AM-33 belongs to the lipocalin family. However, given the low sequence identity between TSGP4, AM-33, FS-HBP2 and OMCI (<20% sequence identity, <30% sequence similarity), the models can only approximate the true structures of TSGP4 and AM-33. However, it should be possible to investigate general features such as topology and overall hydrophobicity within the lipocalin binding cavity.

Residues that lined the binding cavity of the lipocalin beta-barrel were selected and space fill models of their van der Waals radii were constructed for models based on the structure of OMCI (Roversi et al. 2007). Models for TSGP4 and AM-33 indicated that the binding cavity is hydrophobic in character, with polar residues occurring at the periphery of the binding pocket (Fig. 3). This is in contrast to for example, the structure of the histamine and serotonin binding lipocalins from R. appendiculatus and A. monolakensis that possess several polar residues within the binding pocket (Paesen et al. 1999; Mans et al. 2008). Similar results were obtained using models based on the structure of FS-HBP2 (results not shown).

Fig. 3.

Molecular modeling of TSGP4 and AM-33. Indicated are models for TSGP4 (top panels) and AM-33 (bottom panels). The first pair of pictures in each panel shows spacefill and cartoon models of the β-barrel viewed from the side. The second pair of pictures shows the same structures viewed from the top of the β-barrel looking down into the binding cavity. Space fill models indicate non-polar (dark gray) and polar (light gray) residues that lines the binding pocket.

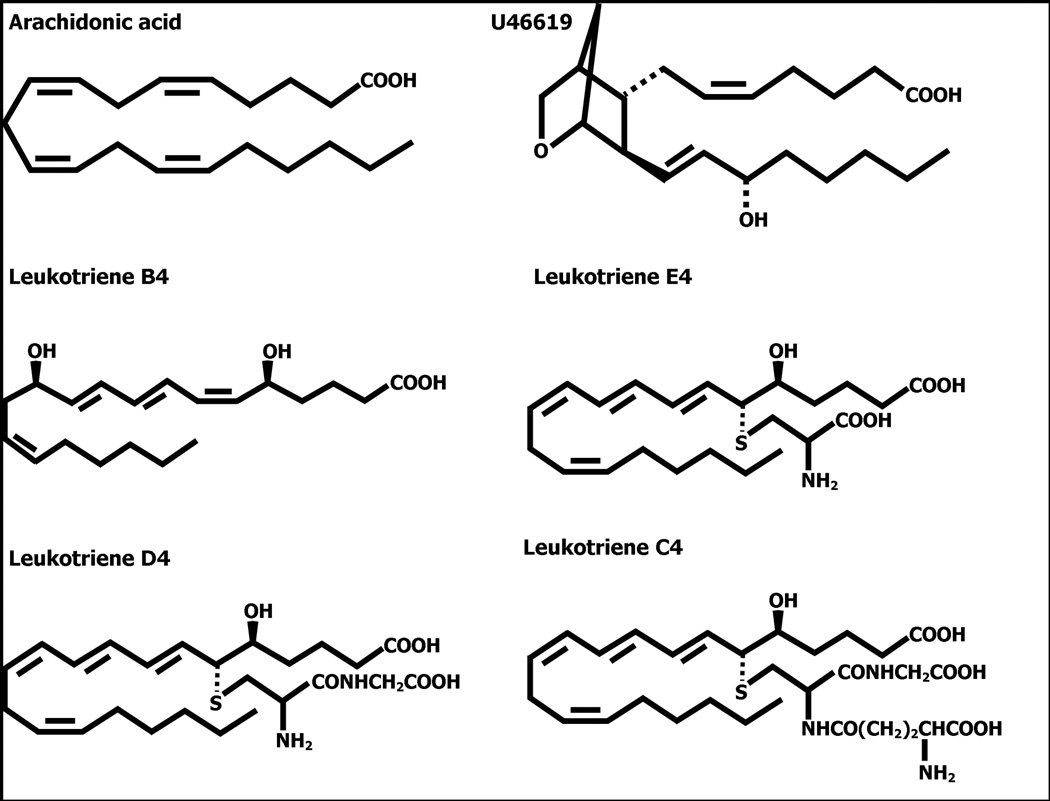

OMCI binds ricinuleic acid and possesses polar residues in the binding pocket that allows interaction with the hydroxyl groups of ricinuleic acid (Roversi et al. 2007). In addition, the OMCI-related proteins moubatin, TSGP2 and TSGP3 was shown to be able to bind LTB4 and TXA2 (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). The overly hydrophobic character of the structure models for TSGP4 and AM-33 thus suggested that they will bind hydrophobic ligands that do not possess any polar groups in the part that binds within the hydrophobic pocket of the beta-barrel. Potential bioactive ligands that fall within this classification will be lipid-derived ligands such as platelet-activating factor, TXA2 or various leukotrienes (Fig. 4). As other soft tick lipocalins were recently found to be able to bind lipid-derived ligands (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008), we investigated the ability of AM-33 and TSGP4 to bind similar ligands.

Fig. 4.

Structures of cysteinyl leukotrienes and related eicosanoids.

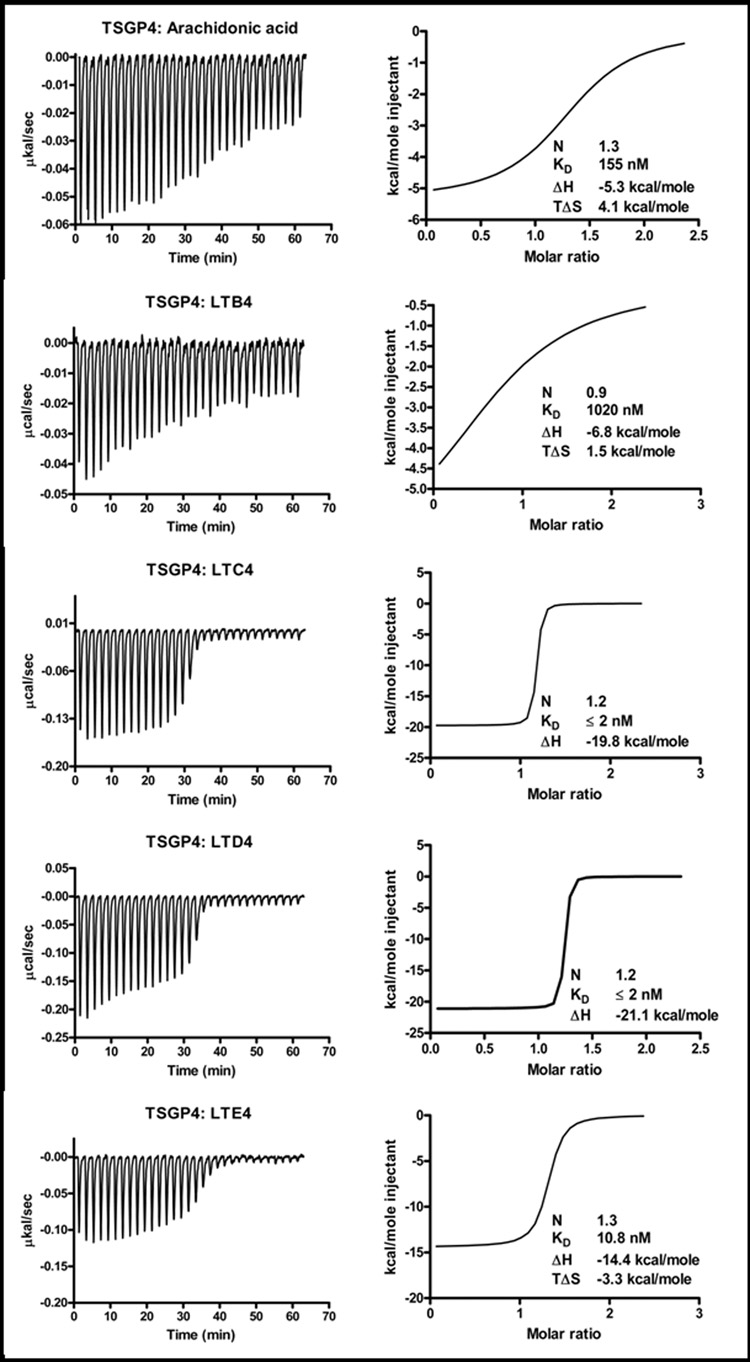

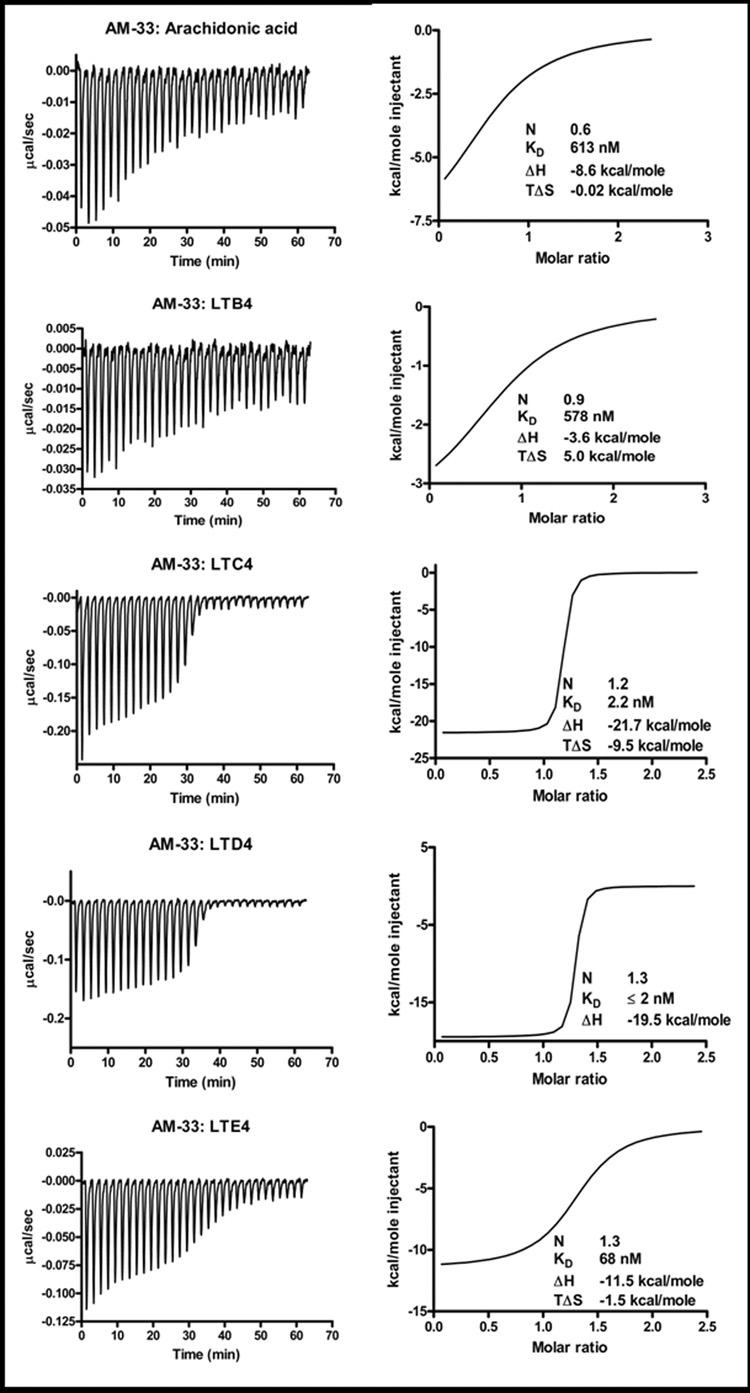

3.4 Binding of hydrophobic bioactive ligands by TSGP4

Binding to hydrophobic ligands by recombinant expressed AM-33 and TSGP4 were tested using micro-calorimetry. No significant binding were observed for the TXA2 analog, U44619 or PAF at the protein concentration (2 µM) tested (results not shown). Arachidonic acid and LTB4 were bound at low affinities by both proteins. However, both bound the cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 with high affinities, in the low nanomolar range (Table 1; Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for binding of arachidonic acid, LTB4, LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4.

| Protein | na | ΔHb | TΔSb | Kdc | ΔGb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSGP4 | |||||

| Arachidonic acid | 1.35 | −5.3±0.2 | 4.1 | 155±43 | −9.4 |

| LTB4 | 0.9 | −6.8±1.7 | 1.5 | 1000±476 | −8.3 |

| LTC4 | 1.1 | −19.7±0.1 | ≤ 2 | ||

| LTD4 | 1.2 | −21.1±0.2 | ≤ 2 | ||

| LTE4 | 1.3 | −14.4±0.2 | −3.3 | 10.8±2 | −11.1 |

| AM-33 | |||||

| Arachidonic acid | 0.7 | −8.6±2 | −0.02 | 613±198 | −8.6 |

| LTB4 | 0.9 | −3.6±0.7 | 5.0 | 587±286 | −8.6 |

| LTC4 | 1.2 | −21.6±0.2 | −9.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | −12.1 |

| LTD4 | 1.3 | −19.5±0.2 | ≤ 2 | ||

| LTE4 | 1.3 | −11.5±0.2 | −1.5 | 68.0±6.6 | −10.0 |

Values indicate the stoichiometry of ligand binding.

Values are given as kcal/mol. S.E.M. represents the deviation of the experimental data from the fitted data.

Values are given as nanomolar. Values indicated as equal or smaller than two have c values not in the 1–1000 range that can be accurately measured by iso-thermal microcalorimetry (Wiseman et al. 1989). S.E.M. represents the deviation of the experimental data from the fitted data.

Fig. 5.

Binding of arachidonic acid, LTB4, LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 by TSGP4. Protein (2µM) was titrated against 20 µM ligand. Indicated are thermodynamic parameters derived for each titration that includes the stoichiometry of binding (N), dissociation constant (KD), change in enthalpy (ΔH) and change in entropy (TΔS) upon binding.

Fig. 6.

Binding of arachidonic acid, LTB4, LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 by AM-33. Protein (2µM) was titrated against 20 µM ligand. Indicated are thermodynamic parameters derived for each titration that includes the stoichiometry of binding (N), dissociation constant (KD), change in enthalpy (ΔH) and change in entropy (TΔS) upon binding.

3.5 Bioassay for TSGP4 and AM-33

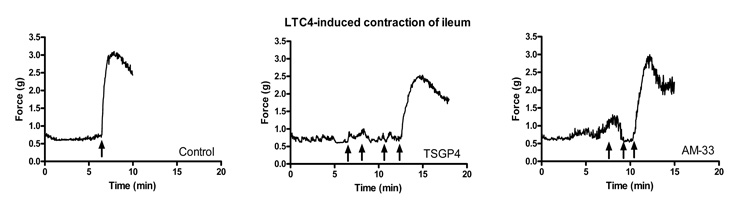

LTC4 and LTD4 act as potent inflammatory mediators released by mast cells and basophils during hypersensitivity reactions (Drazen et al. 1980; Austen, 2008). Before molecular characterization of the cysteinyl leukotrienes, they were known as the slow-reacting substance (SRS) of anaphylaxis, because supernatants of cells undergoing anaphylaxis produced a slow contraction of guinea pig ileum treated with anti-histamines (Austen, 2005). TSGP4 and AM-33 were both able to inhibit contraction of guinea pig ileum by LTC4 in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of LTC4-induced contraction of guinea-pig ileum by AM-33 and TSGP4. Ileum was pre-incubated with TSGP4 or AM-33 at a final concentration of 0.3µM. At set time points (arrows), LTC4 (0.1 µM final concentration) were added to give concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 µM.

3.6 Biological significance of TSGP4 and AM-33

TSGP4 and AM-33 both occurs at 5% and 3.3% of the total salivary gland proteins (Mans et al. 2001; Mans et al. 2008b). If it assumed that only 50% of all salivary gland proteins are secreted during feeding and that the feeding site is between 10–50µl total volume, then TSGP4 (3–18µM) and AM-33 (0.4–2µM) can attain concentrations at the feeding site that is well above the physiological ranges of the cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes (Drazen et al. 1980). Given the high affinity for the cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes and the fact that LTC4 and LTD4 are bio-active at similar concentrations (Drazen et al. 1980), as well as the results from the bioassay, we conclude that both TSGP4 and AM-33 would indeed be important scavengers of the cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes during feeding.

4. Discussion

Cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes derive from the conjugation of glutathione and leukotriene A4 (Austen, 2007). Synthesis occurs in neutrophils, macrophages, basophils and mast cells in response to external stimuli. Neutrophil derived leukotriene A4 are also efficiently converted to LTC4 by platelets (Maclouf and Murphy, 1988). LTC4 are in turn further metabolized to yield LTD4 and LTE4. Collectively these leukotrienes were first characterized as slow reacting substance of anaphylaxis (SRS-A) due to their potent ability as vasoconstrictors of the bronchial and other smooth muscle systems (Austen, 2007; Austen 2008). Although LTC4 is a skin vasodilator and as such should enhance tick blood feeding, it’s profound action in increasing endothelial permeability leads to edema that result in occlusion of blood vessels and decreased blood availability. Upon skin injection of LTC4, erythema and wheal formation occurs within 10 minutes, peaks at 1 hour and persist for more than 2 hours (Soter et al. 1983). At the tick feeding site, this would lead to accumulation of a serous-rich and red cell depleted fluid in the feeding cavity and hence a less efficient blood meal. The time frame observed for erythema and wheal formation falls within that normally described for the feeding of soft ticks that ranges from 15 minutes to a few hours (Hoogstraal, 1985). As such, targeting of cysteinyl leukotrienes would be an important strategy during soft tick feeding.

The present study shows that two related lipocalins, TSGP4 and AM-33 binds cysteinyl leukotrienes with high affinities. Non-cysteinyl leukotrienes (LTB4) and TXA2 analogs (U46619) were not bound with high affinity, indicating specificity towards the cysteinyl leukotrienes. It should be noted that LTB4 and U46619 possess hydroxyl groups at the C12 and C15 carbons, respectively, and that this was previously shown to have been determinants of specificity in the moubatin-clade of lipocalins (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). This could explain the low binding affinities of TSGP4 and AM-33 for LTB4. The cysteinyl leukotrienes, however, lack hydroxyl groups within the saturated hydrocarbon chain and would bind within a predominantly hydrophobic cavity.

The relatively low affinities for arachidonic acid, that is also predominantly hydrophobic, suggest that the peptidyl part of the cysteinyl leukotrienes play an important part in the interaction with the lipocalins. In this regard, there seem to be a direct correlation between the presence of peptidyl region and binding affinity, when binding of LTC4 (5-(S)-hydroxy-6-R-S-glutathionyl) and LTD4 (6-S-cysteinylglycyl) is compared to binding of LTE4 (6-S-cysteinyl), LTB4 and arachidonic acid. This would imply that while the lipid part of the cysteinyl peptide leukotrienes bind within the hydrophobic cavity of the lipocalin fold, that the peptidyl part (especially the terminal cysteinylglycyl) play an important role in the affinity of the lipocalins for the leukotrienes. This correlate with the relatively high negative entalphy measured by microcalorimetry, that suggests that hydrogen bonds contribute significantly to cysteinyl leukotriene binding. On the other hand, the relative positive entropy contribution, suggests that hydrophobic interactions within the lipocalin barrel also play an important role in eicosanoid binding.

TSGP4 as well as another lipocalin (TSGP2) has been previously implicated in the toxicoses induced by the soft tick O. savignyi (Mans et al. 2002; Mans and Neitz, 2004a). It was shown that TSGP2 can bind arachidonic acid and LTB4 (nanomolar affinities) and it was suggested that toxicity may be linked to eicosanoid metabolism within the tick (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). The present study showed that TSGP4 can bind arachidonic acid (Kd~155 nM) as well as cysteinyl leukotrienes (nanomolar affinity). It is thus of interest that two proteins previously implicated in toxicity can both bind arachidonic acid derivatives that have been linked to anaphylactic shock, a recognized symptom in sand tampan toxicoses (Mans et al. 2002; Feuerstein and Hallenbeck, 1987).

In this regard it is of interest that ticks obtain large quantities of arachidonic acid during a blood-meal (Shipley et al. 1993). In soft ticks, adults feed more than once with extended non-feeding periods that may last for months or even years in O. savignyi (Mans and Neitz, 2004b). As such, salivary gland molecules are stored for prolonged periods within the secretory granules of the salivary glands between periods of feeding (Mans et al. 2004a). It is thus possible that arachidonic acid derivatives can partition to lipocalins amenable to high affinity binding. If this is the case for TSGP2 or TSGP4 it would suggest that they can act as carriers of host-derived or tick-transformed arachidonic acid derivatives. Whether the ability to act as transporters of eicosanoid derivatives are related to the pathogenesis of sand tampan toxicoses, remains to be determined. If this is, however, the case it would be a novel mechanism for toxicoses induced by ticks (Mans et al. 2004b).

To date, three major functional classes have been elucidated for the soft tick family of lipocalins that maps to well defined clades (Mans, 2005). This includes biogenic amine scavenging (Mans et al. 2008a), scavenging of TXA2 and LTB4 by the moubatin-clade (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008) and in the present study scavenging of cysteinyl leukotrienes. BLAST analysis and conserved disulphide bonds suggests that the biogenic amine-binding and moubatin-clades are evolutionary closer related than the TSGP4/AM-33 clade (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Similarity of soft tick lipocalins to hard tick biogenic amine-binding proteins also suggests that the latter clade could have been ancestral to the soft tick lipocalin family. If this is the case, scavenging of eicosanoids evolved on two independent occasions in the soft tick lipocalins, once in the ancestral soft tick lineage and once within the Ornithodoros genus, from the same biogenic amine-binding scaffold (Mans et al. 2008a; Mans and Ribeiro, 2008).

The present study adds to the emerging picture on how ticks modulate inflammatory responses by the host. Hard and soft ticks targets ATP, an agonist of neutrophils, via apyrase mediated hydrolysis (Ribeiro et al. 1985; Ribeiro et al. 1991; Mans et al. 1998). Histamine and serotonin are scavenged by lipocalins in both hard and soft ticks (Mans et al. 2008a). TXA2, LTB4 and complement C5 are targeted by the moubatin-related lipocalins from the genus Ornithodoros (Mans and Ribeiro, 2008). Kininases inactivate bradykinin in Ixodes ticks (Ribeiro and Mather, 1998). Soft ticks from both Argas and Ornithodoros genera scavenge LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 using the lipocalin family (this study). This essentially covers most of the known mediators of inflammation and suggests that regulation of the host’s inflammatory response is an important survival strategy for soft ticks. The model of feeding that emerges includes the prevention of neutrophil migration to the feeding site by scavenging of ATP and LTB4. This occurs most probably mainly to prevent neutrophil-platelet interactions that can lead to the formation of LTC4 that will promote edema.

Conservation of function in the soft tick lineage is becoming more apparent. This includes cysteinyl leukotriene scavengers, biogenic amine-binding proteins (Mans et al. 2008a) as well as anti-thrombin and platelet aggregation inhibitors (Mans et al. 2008c). As such, inhibition of blood-coagulation, platelet or thrombocyte aggregation, vasoconstriction and inflammation emerges as some of the dominant targets in soft tick feeding. Leukotriene C4 synthase are conserved within most vertebrates, including bony fishes and amphibians and imply that edematous inflammatory responses were present at least 400 MYA (Bresell et al. 2005; Benton and Donoghue, 2007). This is well before any of the estimates on the origin of ticks and their adaptation to a blood-feeding environment (Mans et al. 2008c). As such, mast cells and basophils, or their equivalent leukocytes, must have been ancient defenses against tick feeding that persist until the modern day (Brown and Askenase, 1985). This would imply that hemostatic and inflammatory responses by the host were the primary hurdles that soft ticks had to overcome during their adaptation to a blood-feeding environment.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Carl Hammer and Mark Garfield of the Research and Technology Branch of the NIAID are thanked for mass spectrometry analysis and Edman sequencing of the recombinant proteins. This work was supported by the intramural research program of the NIAID, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astigarraga A, Oleaga-Pérez A, Pérez-Sánchez R, Baranda JA, Encinas-Grandes A. Host immune response evasion strategies in Ornithodoros erraticus and O. moubata and their relationship to the development of an antiargasid vaccine. Parasite Immunol. 1997;19:401–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1997.d01-236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen KF. The mast cell and the cysteinyl leukotrienes. Novartis Found. Symp. 2005;271:166–175. doi: 10.1002/9780470033449.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen KF. Additional functions for the cysteinyl leukotrienes recognized through studies of inflammatory processes in null strains. Prostaglandins Other Lipid. Mediat. 2007;83:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen KF. The cysteinyl leukotrienes: where do they come from? What are they? Where are they going? Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:113–115. doi: 10.1038/ni0208-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Lovsey RM, Herbert AD, Sternberg MJ, Kelley LA. Exploring the extremes of sequence/structure space with ensemble fold recognition in the program Phyre. Proteins. 2008;70:611–625. doi: 10.1002/prot.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SJ, Askenase PW. Rejection of ticks from guinea pigs by anti-hapten-antibody-mediated degranulation of basophils at cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity sites: role of mediators other than histamine. J. Immunol. 1985;134:1160–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E, Mans BJ, Andersen JF, Ribeiro JM. Function and evolution of a mosquito salivary protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1935–1942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Palo Alto, CA, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Drazen JM, Austen KF, Lewis RA, et al. Comparative airway and vascular activities of leukotrienes C-1 and D in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:4354–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein G, Hallenbeck JM. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes and platelet-activating factor in shock. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1987;27:301–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.27.040187.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Mans BJ, Meng Z, Gudderra N, Veenstra TD, Pham VM, Ribeiro JM. An insight into the sialome of the soft tick, Ornithodorus parkeri. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;38:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogstraal H. Argasid and nuttalliellid ticks as parasites and vectors. Adv. Parasitol. 1985;24:135–238. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmougin F, Thompson JD, Gouy M, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:403–405. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1244–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclouf JA, Murphy RC. Transcellular metabolism of neutrophil-derived leukotriene A4 by human platelets. A potential cellular source of leukotriene C4. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Gaspar AR, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Apyrase activity and platelet aggregation inhibitors in the tick Ornithodoros savignyi (Acari: Argasidae) Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1998;22:353–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1024517209621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Venter JD, Vrey PJ, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Identification of putative proteins involved in granule biogenesis of tick salivary glands. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:1739–1746. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200105)22:9<1739::AID-ELPS1739>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Steinmann CM, Venter JD, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Pathogenic mechanisms of sand tampan toxicoses induced by the tick, Ornithodoros savignyi. Toxicon. 2002;40:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(02)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Louw AI, Neitz AW. The major tick salivary gland proteins and toxins from the soft tick, Ornithodoros savignyi, are part of the tick Lipocalin family: implications for the origins of tick toxicoses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1158–1167. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Neitz AW. Adaptation of ticks to a blood-feeding environment: evolution from a functional perspective. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004a;34:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Neitz AW. The sand tampan, Ornithodoros savignyi, as a model for tick-host interactions. S.A. J. Sci. 2004b;100:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Venter JD, Coons LB, Louw AI, Neitz AW. A reassessment of argasid tick salivary gland ultrastructure from an immuno-cytochemical perspective. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2004a;33:119–129. doi: 10.1023/b:appa.0000030012.47964.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Gothe R, Neitz AW. Biochemical perspectives on paralysis and other forms of toxicoses caused by ticks. Parasitology. 2004b;129:S95–S111. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003004670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ. Tick histamine-binding proteins and related lipocalins: potential as therapeutic agents. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2005;6:1131–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Ribeiro JM, Andersen JA. Structure, function and evolution of biogenic amine-binding proteins in soft ticks. J. Biol. Chem. 2008a doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800188200. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Andersen JF, Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Schwan TG, Pham VM, Garfield MK, Hammer CH, Ribeiro JM. Comparative sialomics between hard and soft ticks: Implications for the evolution of blood-feeding behavior. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008b;38:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Andersen JF, Schwan TG, Ribeiro JM. Characterization of anti-hemostatic factors in the argasid, Argas monolakensis: implications for the evolution of blood-feeding in the soft tick family. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008c;38:22–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Ribeiro JM. Function, mechanism and evolution of the moubatin-clade of soft tick lipocalins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.06.007. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesen GC, Adams PL, Harlos K, Nuttall PA, Stuart DI. Tick histamine-binding proteins: isolation, cloning, and three-dimensional structure. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Makoul GT, Levine J, Robinson DR, Spielman A. Antihemostatic, antiinflammatory, and immunosuppressive properties of the saliva of a tick, Ixodes dammini. J. Exp. Med. 1985;161:332–344. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.2.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM. Role of saliva in tick/host interactions. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1989;7:15–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01200449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Endris TM, Endris R. Saliva of the soft tick, Ornithodoros moubata, contains anti-platelet and apyrase activities. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 1991;100:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(91)90190-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Mather TN. Ixodes scapularis: salivary kininase activity is a metallo dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase. Exp. Parasitol. 1998;89:213–221. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM. Role of arthropod saliva in blood feeding: sialome and post-sialome perspectives. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2003;48:73–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.060402.102812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roversi P, Lissina O, Johnson S, Ahmat N, Paesen GC, Ploss K, Boland W, Nunn MA, Lea SM. The structure of OMCI, a novel lipocalin inhibitor of the complement system. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MM, Dillwith JW, Bowman AS, Essenberg RC, Sauer JR. Changes in lipids of the salivary glands of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, during feeding. J. Parasitol. 1993;79:834–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soter NA, Lewis RA, Corey EJ, Austen KF. Local effects of synthetic leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, and LTB4) in human skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1983;80:115–119. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster M, Prado ES. Glandular kallikreins from horse and human urine and from hog pancreas. Meth. Enzymol. 1970;19:681–699. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 1989;179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]