Abstract

The present study describes the pattern of connections of the ventral premotor cortex (PMv) with various cortical regions of the ipsilateral hemisphere in adult squirrel monkeys. Particularly, we 1) quantified the proportion of inputs and outputs that the PMv distal forelimb representation shares with other areas in the ipsilateral cortex and 2) defined the pattern of PMv connections with respect to the location of the distal forelimb representation in primary motor cortex (M1), primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and the supplementary motor area (SMA). Intracortical microstimulation techniques (ICMS) were used in four experimentally naïve monkeys to identify M1, PMv and SMA forelimb movement representations. Multi-unit recording techniques and myelin staining were used to identify the S1 hand representation. Then, biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; 10000MW) was injected in the center of the PMv distal forelimb representation. Following tangential sectioning, the distribution of BDA-labeled cell bodies and terminal boutons was documented. In M1, labeling followed a rostro-lateral pattern, largely leaving the caudo-medial M1 unlabeled. Quantification of somata and terminals showed that two areas share major connections with PMv: M1 and frontal areas immediately rostral to PMv, designated as frontal rostral area (FR). Connections with this latter region have not been described previously. Moderate connections were found with PMd, SMA, anterior operculum and posterior operculum/inferior parietal area. Minor connections were found with diverse areas of the precentral and parietal cortex, including S1. No statistical difference between the proportion of inputs and outputs for any location was observed, supporting the reciprocity of PMv intracortical connections.

Keywords: corticocortical, motor cortex, neuroanatomy, PMV, topographic map, ipsilateral

Introduction

The ventral premotor cortex (PMv) of primates is a motor area in the frontal cortex that participates in head and forelimb movements (Nudo and Masterton, 1990; Preuss, 1993; Kaas, 2004; Wise, In press-a). While numerous studies have documented its functional attributes and intracortical connections, the detailed topographic relationship of PMv with other sensorimotor regions of the cerebral cortex is still unclear due to the variety of techniques and varying levels of precision that have been employed in different tract-tracing studies. The present study was designed to describe more specifically and quantitatively, the pattern of connections between the distal forelimb area of PMv and other cortical regions of the ipsilateral hemisphere known to be involved in hand function. This study was conducted in the squirrel monkey due to the accessibility of PMv in this largely lissencephalic primate, and to our extensive experience in the neurophysiology of sensorimotor areas in this particular species.1

Based primarily upon studies in macaque monkeys (Godschalk et al., 1984; Matelli et al., 1986; Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Kurata, 1991; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995; Tanné-Gariepy et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002), PMv shares reciprocal connections with other motor and association areas of the frontal cortex (M1, SMA, PMd, cingulate motor areas, frontal opercular areas), as well as somatosensory, visual, polysensory and visuomotor areas of the parietal cortex (area 7b, secondary somatosensory area, parietal ventral cortex, anterior intraparietal area, ventral intraparietal area). However, several inconsistencies and gaps in our knowledge warrant further clarification. First, since many studies did not physiologically identify the sites of origin and termination, the topographic specificity of PMv connections with other cortical areas is understood in only a general way (Matelli et al., 1986; Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Kurata, 1991; Stepniewska et al., 1993; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995). For example, because of functional differences between the rostral and caudal aspects of the M1 forelimb area (Strick and Preston, 1982b; Strick and Preston, 1982a; Martin, 1991; Li and Martin, 2000; Nudo et al., 2000), more precise information regarding the topographic specificity of these connections is needed (Kaas et al., 1979). Second, very limited quantitative information regarding PMv connections is available. Only three studies have quantified the numbers of neurons projecting to the physiologically defined PMv from various cortical regions (Ghosh and Gattera 1995; Tanné-Guariepy et al., 2002; Dum and Strick, 2005), and only Ghosh and Gattera quantified these connections across the entire hemisphere. This information could be of considerable interest in evaluating the strength of connections between PMv and other cortical areas, and thus might provide insights on its functional interactions and reciprocity. Third, most studies have employed retrograde tracers; few studies have directly examined terminal distribution of intracortical fibers originating in PMv (Matelli et al., 1986; Barbas and Pandya, 1987), thus leaving the question of reciprocity inadequately addressed.

In an attempt to clarify these issues, we examined the pattern of ipsilateral cortical connections of the PMv distal forelimb area in four adult squirrel monkeys using injections of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, 10000MW), a neuroanatomical tracer that allows detailed analysis of anterograde and, to a lesser extent, retrograde transport patterns (Veenman et al., 1992). This detailed description of topographic specificity and quantitative assessment of PMv’s inputs and outputs with other cortical regions provides important information that should increase our understanding of PMv’s role in motor control.

Methods

Surgical procedures

Four adult squirrel monkeys (Saimiri spp.) were used in the present study (weight range = 645g to 1229g). All animal use was in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center. All surgical and neurophysiological procedures, as well as injections of neuronal tracers were effected on the hemisphere contralateral to the preferred hand on a reach-and-retrieval task (see Nudo et al., 1992 for details). Surgeries were performed using aseptic techniques and halothane-nitrous oxide anesthesia. Following a craniectomy over the lateral portion of the frontal cortex, exposing the M1 and PMv distal forelimb areas, a plastic cylinder was fitted over the opening and used to contain warm, sterile silicone oil. A digital photograph of the exposed cortex was taken and subsequently used to create a two dimensional map of motor representations superimposed on the vascular landmarks. After the photograph was taken, the halothane was withdrawn, ketamine-Valium (diazepam) was administered intraveneously, and vital signs were monitored throughout the remainder of the experiment. A first surgical procedure was performed for motor mapping purposes. In three animals (1934, 1892, 3024), somatosensory mapping and BDA injections were done in a second surgical procedure in which the parietal cortex was exposed. For a fourth animal (9409), injections were performed directly after motor mapping.

Derivation of motor maps

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) techniques were used to derive neurophysiological maps of movement representations to identify the functional topography of M1 and PMv in each of the four animals and SMA in one animal (particularly the distal forelimb area). A microelectrode, made from a glass micropipette tapered to a fine tip and filled with 3.5M NaCl, was used for electrical stimulation applied at a depth of ~1750μm (layer V). Typical ICMS parameters were used (Nudo et al., 1992; Nudo and Milliken, 1996); 40ms pulse trains delivered at 350Hz were repeated at 1Hz intervals; current was limited to 30μA or less. Movements were described using conventional terminology (Gould et al., 1986). We defined and included in the distal forelimb representation all sites at which electrical stimulation elicited movements of the digits, wrist or forearm. We grouped these movements based on functionality. Elbow and shoulder movements direct the entire arm and/or forearm through space. Wrist and forearm supination/pronation movements orient the hand within a fixed space. Further, as defined, the distal forelimb representation comprises a contiguous region typically surrounded by the more proximal elbow and shoulder representations in primary and premotor areas.

Sites at which the stimulation elicited movement of the elbow, shoulder or no response determined the physiological border of the distal forelimb representation. In two animals (1934 and 1892), M1 and PMv were mapped at relatively low resolution (~ 500μm interpenetration distances); for two other animals (9409 and 3024), M1 was mapped at higher resolution (~ 250μm interpenetration distances) and PMv at low resolution (500μm). In one animal (1892), SMA also was mapped at low resolution. The lower resolution was sufficient for defining the borders of the distal forelimb representations and for locating the sites for injection of neuroanatomical tracing agents. Surface area measurements were subsequently obtained using a graphics program (Canvas 3.5; Deneba systems, Inc.) by drawing polygons circumscribing sites where movement of similar body segments was elicited by ICMS.

Derivation of somatosensory maps

Techniques for microelectrode recording of multiunit neuronal activity were used to define cutaneous and muscle/joint fields in areas 3a, 3b and 1/2 (Snow et al., 1988; Nudo, 1997; Barbay et al., 1999). Briefly, a glass micropipette similar to that used for ICMS procedures was used for somatosensory recording (impedance = 1–1.5 MΩ). The microelectrode was lowered perpendicular to the cortical surface and the depth adjusted to optimize the sensory signal (depth range of 400–1000 μm). Signals were filtered, amplified and played over a loudspeaker for monitoring. Minimal cutaneous receptive fields were defined by determining the skin field over which cortical neurons were driven by just visible indentation of the skin with a fine glass probe. Adequate sensitivity for defining the response as cutaneous (as opposed to muscle/joint input) was then determined by using modified von Frey hairs (Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments) to elicit the multi-unit response (i.e., using a filament smaller than 3.61; Nudo, 1997). Deep receptive fields were defined by high threshold stimulation and/or joint manipulation. Areas 3a, 3b and 1/2 were differentiated on the basis of the stimulus that reliably drove responses in component neurons and by reversal of somatotopic gradients (Kaas, 1993). While cutaneous and muscle-joint responses can also be recorded in M1 (area 4), the area 3a/4 border can be determined because thresholds for evoking movements with ICMS are greater in area 3a than in area 4.

In area 3b, we made one or two medio-lateral row(s) of microelectrode penetrations at ~ 250μm interpenetration distances to identify all five digits and the medial and lateral boundaries of the hand representation. An additional two rostro-caudal row(s) of microelectrode penetrations were made at a similar resolution to identify the area 3b/area-1/2 border. Whereas this method did not provide extensive detail on the internal organization of these areas, it allowed precise identification of borders, particularly between areas 3a and 3b, between areas 3b and 1/2 and the location of the medial and lateral borders of the hand representation in area 3b.

Injection of neuronal tracer

Following the physiological mapping procedures, the animal was returned to halothane-nitrous oxide anesthesia for the injection of neuronal tracers. Biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; 5% BDA in saline solution; 10,000 MW conjugated to lysine; Molecular Probes) was injected into the center of the PMv distal forelimb area. The injection in case 1934 was made via pressure injection with a microsyringe pump controller (UPP2-1, WPI instruments) and a 1μl Hamilton syringe (injected volume = 0.2μl). The injection in cases 1892 and 3024 were made via pressure injection with the microsyringe pump controller through a tapered, graduated micropipette (Fisher Scientific Company; injected volume = 0.2μl). The addition of the micropipette resulted in a more concise injection core. In case 9409, the injection was performed using electrophoresis (6μA positive current 7s on/7s off for 10 min.). In each animal, injections were made at multiple depths in order to label a column of PMv cortex through all six layers of the grey matter.

Tissue preparation

Twelve days following tracer injection, the animal was euthanized with a lethal dose of Euthasol (390mg pentobarbital sodium/50mg phenytoin sodium per 100ml) injected intra-abdominally. The animal was then perfused with 0.2% heparin/lidocaine in a 0.9% saline solution followed by 3% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), the brain removed and the cerebral cortex separated from the rest of the brain. The parietal and frontal cortex was then flattened between two glass slides (Gould and Kaas, 1981). The cortical block was post-fixed, cryoprotected and sectioned tangential to the cortical surface (thickness = 50μm). Every third section was used for histological processing to examine the presence of BDA, allowing us to document the distribution of terminal boutons of PMv and cell bodies of other cortical areas projecting to PMv at increments of ~150μm in depth through the cortical grey matter (approximate, since some compression occurs during flattening). Other sections (1/3) were used for a myelin staining protocol (see below).

BDA histochemistry

Briefly, sections were washed in a 0.4% Triton X-100/0.05 KPBS and then rinsed in a 0.05 potassium phosphate buffer solution (KPBS) before overnight incubation in the A-B solution (Vectastain® ABC kit; Elite; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The following day, sections were rinsed again prior to the peroxidase reaction (incubate 5 to 10 minutes in a 0.05% diaminobenzidine (DAB) 0.015% H2O2 in 0.1KPBS). The peroxidase reaction was ended by repetitively passing sections through several 0.1 KPBS rinses and then the sections were mounted on subbed slides. Mounted sections were dried overnight, dehydrated in ascending alcohol solutions the next day and kept in fresh xylene for four days. They were then rehydrated and incubated in a 1.42% AgNO3 solution for 1 hour at 56ºC. Sections were alternatively rinsed between solutions of 0.2% HAuCl4 for 10 minutes and 5% Na2S2O3 for 5 minutes. Following the last rinse, they were dehydrated and coverslipped from fresh xylene.

Myelin staining

To further facilitate identification of functional boundaries within the parietal cortex, we used tangential sections stained for myelin in each of the four cases (Gallyas, 1979; Krubitzer and Kaas, 1990). Sections were mounted and reacted with pyridine/acetic anhydride solution, hydrated and reacted with increasing acetic acid solution, incubated in silver nitrate solution for one hour and then put back into acetic acid solution. Finally, a solution of anhydrous sodium carbonate, ammonium nitrate, silver nitrate, silicotungstic acid and formaldehyde was used as the developer. Sections were alternately passed through the developer and potassium ferriacyanide to increase contrast between areas.

Quantitative neuroanatomical analyses

A neuroanatomical reconstruction system, consisting of a computer-interfaced microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) and associated software (Neurolucida: Microbrightfield, Inc.), was used to record the locations of labeled terminals and cell bodies.

Documentation of terminal labeling

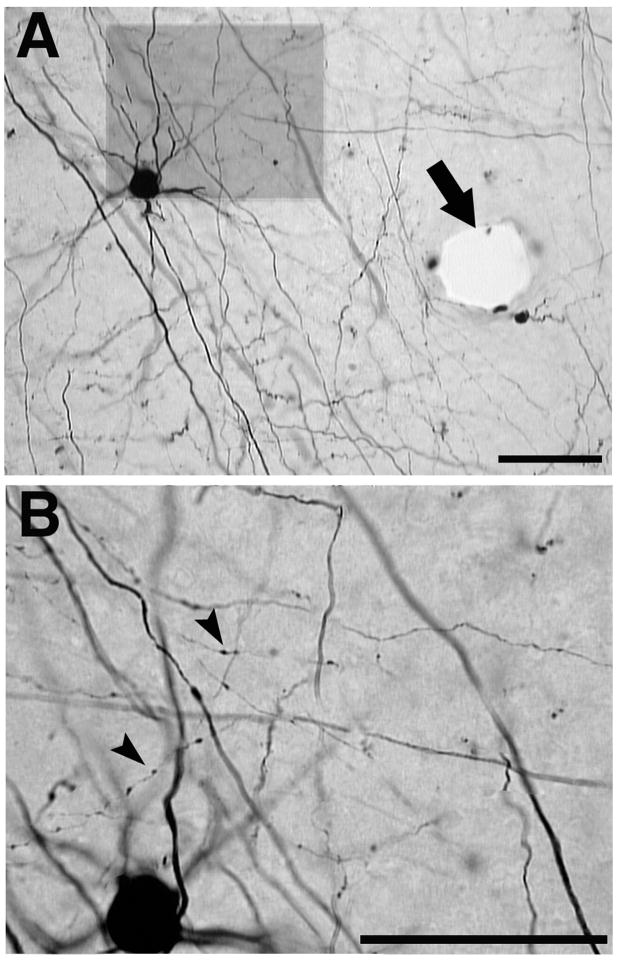

A varicosity was considered to be a terminal bouton if it appeared as a small, darkly labeled sphere contacting a small fiber (Figure 1). Terminal distribution was found to be consistent through depths approximately corresponding to layers II to VI of the gray matter. Thus, for quantitative comparisons, two representative slides per animal were sampled at depths roughly corresponding to layers II/III and V (situated at depths of ~500–600 μm and ~1600–1800 μm, respectively where most corticocortical cells are expected to be found). We sampled the selected slides using a grid pattern (100 × 100μm) overlaid on the section image. If at least two terminals were located within a square of the grid at any depth within the section, a marker was placed in the center of the square. The results provide information on the number and density of 100 × 100 × 50μm voxels with labeled terminals.

Figure 1. Example of cell body and terminal labeling.

A: Cell bodies, often with multiple dendrites, were darkly stained at most locations in the ipsilateral hemisphere. This cell body was located in the rostral portion of the M1 distal forelimb representation. B: Terminals were also clearly stained in the entire hemisphere. When observed at higher magnification, terminals showed clear labeling in all cases. Example of a labeled small fiber with terminals is magnified (arrowheads). Additionally, an example of blood vessel is shown (arrow). Due to the section thickness, several pictures taken at different depths needed to be combined for clarity. Brightness and contrast were also adjusted. Scale bar = 50μm.

Six to seven sections at depths of 500 to 1850μm depths were used to document the location of labeled cell bodies in each hemisphere. Labeled cell bodies that displayed a full rounded soma and at least two darkly stained protuberances (considered to be dendrites or the axon) were marked in Neurolucida (Figure 1).

Data co-registration

To enable alignment of BDA sections with photographs of myelin stained sections and with the physiological maps, the spherical holes representing selected large blood vessels were marked on each section (Xiao and Felleman, 2004). The plotted BDA sections were then overlaid and aligned to the myelin sections in a graphics program (Photoshop, Adobe). Contrast and brightness of photographs were also adjusted using this software. Similarly, the penetration locations of large blood vessels were outlined on the digital photographs used for the ICMS map and matched to the pattern in BDA and myelin stained sections. After aligning all three sets of sections, we used Neurolucida to draw contours around clusters of BDA labeling within the physiologically-defined M1, SMA, and S1 distal forelimb areas. The number of BDA labeled voxels or cell bodies in each area was determined with Neuroexplorer, an analysis program linked to Neurolucida.

Measurement of BDA injection core

For each case, the section showing the largest injection core was identified using a dissecting microscope. A contour was drawn on the section reconstruction (Neurolucida, Microbrightfield, Inc.) to circumscribe the core and include part of the transition zone of the surrounding halo. The size of the effective injection site was subsequently determined with Neuroexplorer. It should be noted that in each of the four cases, the core was visible on all sections and the area of the core was consistent throughout the depths of the cortex. Thus whereas we report area measurements, the cores formed vertical columns ~ 1900 μm in height.

Results

Identification of PMv, M1, SMA and PMd distal forelimb representations

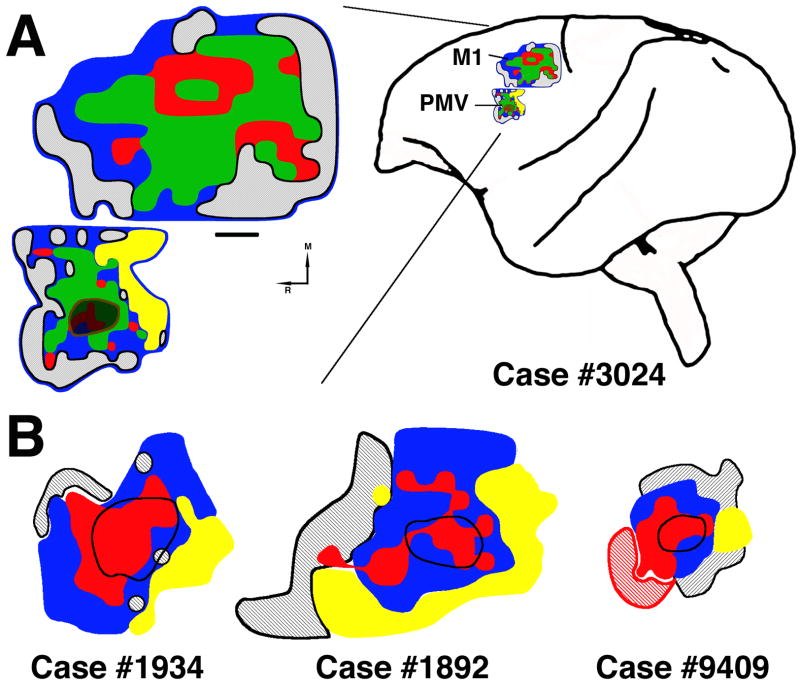

The M1 distal forelimb representation was found immediately rostral to the central sulcus (Woolsey, 1952; Welker et al., 1957; Strick and Preston, 1982a; Nudo et al., 1992). The PMv distal forelimb representation was found ventral and rostral to M1. Figure 2A depicts movement representations in M1 and PMv resulting from a typical ICMS experiment. In this case, the surface area of the M1 distal forelimb representation was 14.1mm2, while the surface area of the PMv distal forelimb representation was 3.5mm2. The mean M1 distal forelimb area was 12.6 ± 2.8 mm2 (n=4), while the mean PMv distal forelimb area was 4.2 ± 0.8 mm2 or roughly 1/3 of the size of the M1 distal forelimb representation (n=3; rostro-lateral border of the PMv map for 9409 was incomplete, and thus, not included; Table 1). The mean distance between the M1 and PMv distal forelimb representation borders was 1.9mm ± 0.5 (n=4).

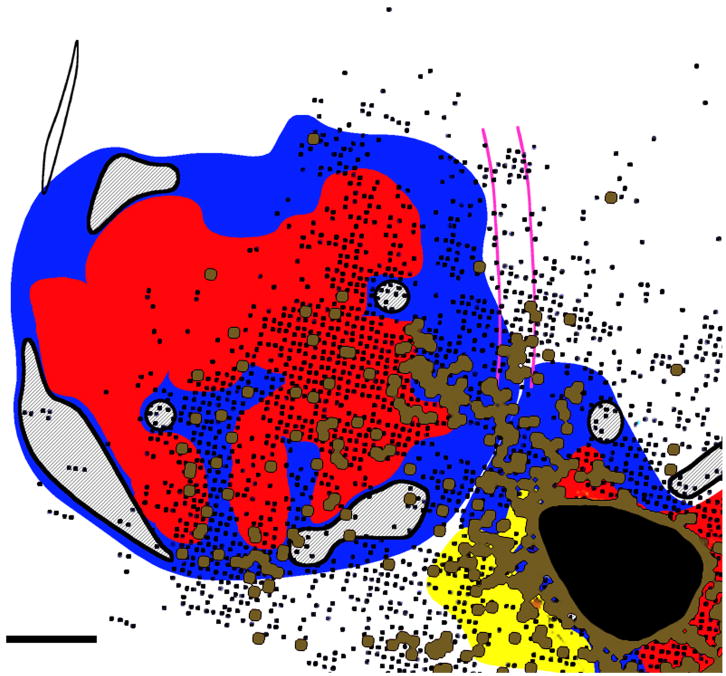

Figure 2. Example of neurophysiological motor maps.

A: Illustration of the M1 and PMv distal forelimb representations as defined by ICMS. Sites whose stimulation evoked movements of the digits, wrist and forearm comprised the distal forelimb representation. Stimulation of surrounding sites evoked proximal movements (elbow, shoulder, trunk or face) or no response (≤ 30μA). Injection core located in PMv is shown in brown. Precise localization of the boundary of the injection core in relation to the motor map was possible with alignment of surface blood vessels indicated by holes in serial tangential sections. Red = digits; green = wrist/forearm; blue = proximal; hatched black = non responsive; M=Medial; R=Rostral. Scale bar = 1mm. B: Location of injection core in other three cases in relation to the distal forelimb representation (combination of digits and wrist; red). In all cases, the core was confined to the upper extremity representation, primarily within the distal forelimb representation. Due to the mosaical arrangement of movement representations in PMv, the injection core also overlapped a small portion of the proximal representation (blue), but did not encroach on the face representation (yellow). Hatched red in case 9409 was not physiologically defined due to the craniotomy border and that was estimated to be a part of the distal forelimb representation.

Table 1.

Summary of BDA injections.

| Case | M1 distal forelimb representation area (mm2) |

PMV distal forelimb representation area (mm2) |

Injection area (mm2) |

Injection Size Category |

Labeled cell bodies* (# per section) |

Labeled voxels* (# per section) |

Movement representations within the injection core |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No response (%) | Proximal (%) | Distal forelimb (%) | |||||||||

| Wrist/Forearm | Digits | Total | |||||||||

| 1934 | 15.0 | 5.2 | 3.3 | Large | 154.4 | 4266 | 1.2 | 13.5 | 68.5 | 16.8 | 85.3 |

| 1892 | 12.9 | 4.0 | 1.9† | Large | 110.1 | 6680 | 0 | 32.1 | 5.7 | 62.2 | 67.9 |

| 9409 | 8.5 | 3.8§ | 0.9 | Small | 60.6 | 3824 | 0 | 16.2 | 13.7 | 70.1 | 83.8 |

| 3024 | 14.0 | 3.5 | 0.8 | Small | 69.5 | 3480 | 11.9 | 0 | 54.8 | 33.3 | 88.1 |

Note that numbers of labeled cells (or labeled voxels) per section are reported. For an approximation of the total number of labeled cells in the entire hemisphere, the number of cells per section must be multiplied by the total number of sections through the cortical gray matter. Therefore, the total # BDA-labeled cell bodies in the entire hemisphere is estimated to be 4170 (case 1934); 2974 (1892); 1635 (9409) and 1876 (3024). Note that these are general estimates since unbiased stereological techniques would be required for appropriate determination of actual numbers. The present data is appropriate, however, for estimates of proportions in each area.

This numbers is approximate because a portion of the dense core of this injection was absent in this case. This missing portion was considered to be fully contained in the core of the injection site (see methods).

This number is an estimate of PMV size since the rostral border was not completely exposed in the craniotomy in this case. Exposed PMV distal forelimb representation was actually 2.35mm2. See Figure 2 (case #9409; hatched red)

In one case (1892) additional ICMS mapping was conducted to identify the location of the SMA distal forelimb representation. A cluster of sites whose stimulation evoked movements of the distal forelimb was found ~12mm medial to the PMV distal forelimb representation, near the medial convexity.

We defined the area located between PMv and SMA, and rostral to M1 as PMd, attributing to that area the same caudo-rostral width found for PMv. Although not explored in detail in the present study, the border between M1 and PMd was defined based on a statistical analysis of physiological mapping data obtained in several other squirrel monkeys in this laboratory. Based on this analysis, BDA-labeled cells and terminals that were more than ~1 mm rostral to the M1 distal forelimb area were considered to be within PMd. The M1/PMd border was consistently assigned to each case in the present study based on the position of the physiologically-defined M1 distal forelimb area.

Identification of other frontal areas

In addition to areas where boundaries were identified precisely using neurophysiological mapping, boundaries of other areas in the frontal cortex were defined with less certainty. These additional designations were conservative approximations based on myelin staining (Krubitzer and Kaas, 1990; Jain et al., 2001), anatomical landmarks and comparison with other physiological and anatomical studies (Preuss and Goldman-Rakic, 1989).

Identification of S1 hand representations

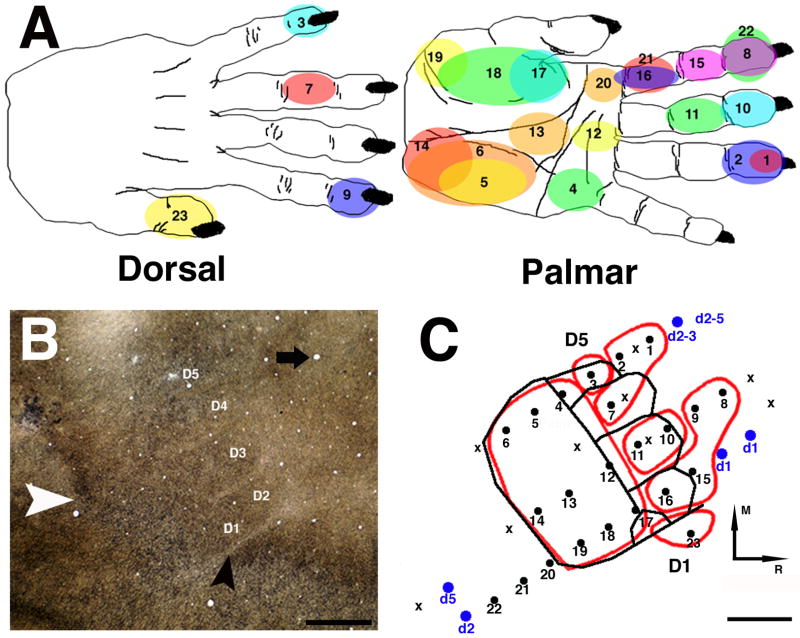

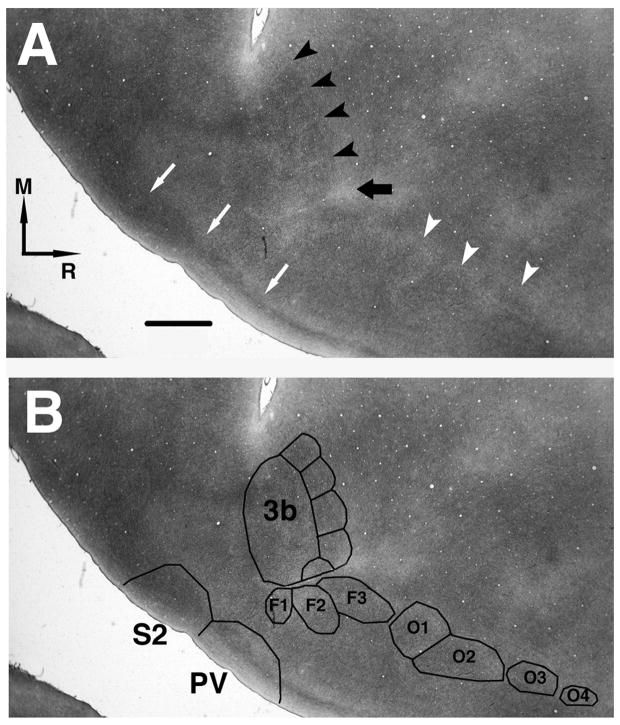

In three of the four cases (1934, 1892, 3024), neurophysiological recordings of multi-unit activity in S1 were obtained by stimulation of cutaneous and deep receptors in the contralateral hand. As in previous studies, area 3b was arranged in a somatotopic fashion, with receptive fields on digit 5 and the ulnar aspect of the hand located medially and those on digit 1 and the radial aspect of the hand located laterally (Kaas, 1993). Progressing in a rostral-caudal direction, receptive fields were ordered from the distal to proximal phalanges, respectively. Caudal to the digit area, receptive fields were found on the palmar surface. Area 1/2 was characterized by markedly larger receptive fields and a somatotopic reversal. That is, receptive fields were found on progressively more distal locations on the hand as the microelectrode was advanced in a rostral to caudal direction caudal to the 3b border (Figure 3A). Eventually, receptive fields located on the digits were once again found caudal to palmar fields, though multi-digit receptive fields were more common than in area 3b. Based on these observations, a border between area 3b and area 1/2 could be defined. The average size of the area 3b hand representation defined by neurophysiological mapping techniques was 10.2±1.0mm2 (n=3), which is within 10% of the size that was previously reported in squirrel monkeys by other investigators (Xu and Wall, 1999).

Figure 3. Verification of co-registration of area 3b digit representations as defined by multi-unit recording of cutaneous receptive fields and myeloarchitecture.

We verified that the 3b hand area was reliably identified by either electrophysiological or histological approaches. A: Orderly arrangement of receptive fields in S1. Numbers in the receptive fields correspond to the numbers on the physiological map shown in C. Note the somatotopic reversal between sites 19 and 20, indicating the border between area 3b and area 1/2.B: Area 3b hand representation shown with myelin staining in a tangential section through the ipsilateral cortex. White arrowhead shows caudal border of the hand area. Black arrowhead shows the hand-face septum. Black arrow shows an example of blood vessel used for alignment of myelin section with sensory map. Brightness and contrast were adjusted. M=Medial; R=Rostral. Scale bar = 1mm. C: Superposition of the myeloarchitectonically defined hand area (black contour) onto sensory maps obtained with multi-unit recordings used to define the area 3b hand representation (red contour) in the same case. Alignment of blood vessel locations was used to co-register the two sets of data. Each recording site is represented by a dot. Sites where no response was elicited are indicated by an “x”. Sites where responses were evoked by joint movements, but not by cutaneous stimulation, are indicated by blue dots. Receptive field is indicated beneath each blue dot. In all cases, the typical somatotopic arrangement in S1 was found with digit 1 (thumb) located laterally and digit 5 medially. The representations of the distal phalanges were located in the rostral aspect of the area 3b hand map, while the representation of the palm was located in the caudal aspect. Scale bar = 1mm.

Delineation of granular regions of the cerebral cortex using myelin staining was similar to that described in previous papers (Jain et al., 1998). This technique was particularly useful for histological confirmation of the caudal and rostral borders of the area 3b hand representation, and the location of the hand/face septum (Figure 3B). It was also possible to identify individual digit zones within the 3b hand representation in some myelin-stained sections. Overlay of the neurophysiological and neurohistological data sets was achieved locally within the 3b hand area by matching of corresponding blood vessel patterns (Figure 3C). This analysis confirmed high inter-reliability of the two approaches with regard to definition of the area 3b borders.

Evaluation of BDA injection location

Registration of the injection core to the neurophysiological map of the PMv distal forelimb representation was performed using similar methods for vascular alignment as those described above. In general, we produced two small injections (cases 9409 and 3024) and two relatively larger injections (cases 1934 and 1892). In each case, the dense core area was smaller than, and confined to, the limits of the PMv forelimb representation as defined by ICMS procedures (Table 1; see also Figure 2 for location of core in relation to the distal forelimb representation).

Distribution of labeled cell bodies and terminals in the ipsilateral cortex after BDA injection into PMv

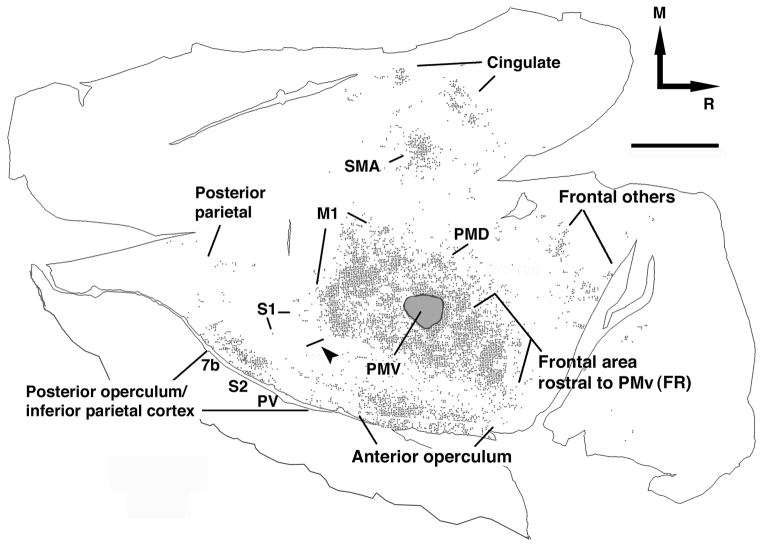

The distribution of voxels with labeled varicosities (hereafter called terminals) in a case with a large BDA injection is shown in Figure 4. Where BDA labeling occurred, cell bodies, dendrites, axons and terminals were intensely labeled, indicating that connections with PMv are reciprocal throughout the hemisphere. No significant differences were found between the magnitude of cell body or terminal labeling in any of the areas. Because of the reciprocity of connections, unless otherwise noted, qualitative results regarding PMv connections refer to both terminals and cell bodies.

Figure 4. Ipsilateral terminal distribution following a relatively large injection in the PMV distal forelimb representation.

Distribution of terminals in case 1934. Each dot represents a voxel (100 ×100μm resolution; approximate depth 1500μm) in which at least two labeled variscocities were identified. Functional areas are indicated for various clusters of labeled voxels. A black arrowhead shows the location of the hand face septum (black line). M=Medial; R=Rostral. Scale bar = 5mm.

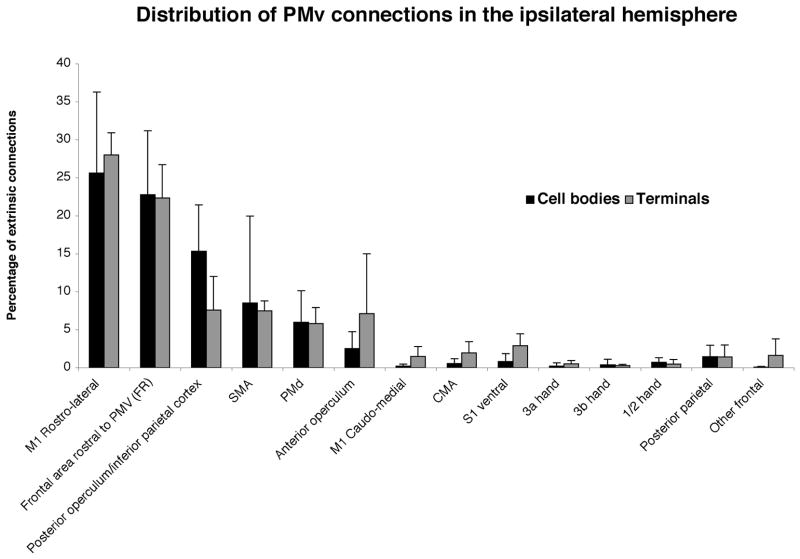

Figure 5 depicts the magnitude of cell body and terminal labeling in each of 14 cortical regions expressed as a percentage of all labeled cell bodies and terminals in the ipsilateral hemisphere (excluding those within PMv in the immediate vicinity of the injection core; see Table 2 for individual case results). These 14 regions account for 85% of all cell bodies and 89% of all terminals in the hemisphere. An ANOVA examining the effects of area and label type (cell body or terminal) revealed a significant main effect of area (F=32.23, p<.0001). However, there was no label type by area interaction (F=1.10, p=0.37).

Figure 5. Proportion of labeled terminals and cell bodies in various areas of the ipsilateral cortex.

The frontal cortex shared many more connections with PMV than the parietal cortex. The rostro-lateral M1 and the frontal area rostral to PMv were the areas that shared the most connections with PMV (major connections). Numerous connections were also shared with SMA, PMd, the posterior operculum/inferior parietal area (7b, S2, PV) and the anterior operculum.

Table 2.

Distribution of terminal and cell body labeling across cases

| 1934 | 1892 | 9409 | 3024 | Mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell bodies (%) |

Terminals (%) |

Cell bodies (%) |

Terminals (%) |

Cell bodies (%) |

Terminals (%) |

Cell bodies (%) |

Terminals (%) |

Cell bodies (%±sd) |

Terminals (%±sd) |

|

| Total* | 87.3 | 92.0 | 77.3 | 87.3 | 93.0 | 91.1 | 82.4 | 85.0 | 85.0±6.7 | 88.9±3.3 |

| M1rl | 37.3 | 29.0 | 21.0 | 24.7 | 13.2 | 31.5 | 30.9 | 26.8 | 25.6±10.7 | 28.0±2.9 |

| M1cm | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2±0.2 | 1.5±1.3 |

| PMd | 1.7 | 5.0 | 11.6 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 6.0±4.2 | 5.8±2.1 |

| SMA | 3.8 | 5.6 | 0.4 | 7.6 | 25.4 | 8.2 | 4.4 | 8.5 | 8.5±11.4 | 7.5±1.3 |

| CMA | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | -- | -- | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.7±0.6 | 2.6±0.8 |

| FR | 13.9 | 18.1 | 27.5 | 19.1 | 32.0 | 26.9 | 17.6 | 25.3 | 22.7±8.4 | 22.3±4.4 |

| AO | 4.4 | 18.2 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 2.5±2.2 | 7.1±7.9 |

| Other frontal | 0.2 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1±0.1 | 1.6±2.2 |

| 3b hand | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.3±0.1 |

| S1 ventral | 2.3 | 2.6 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.8±1.0 | 2.9±1.6 |

| 3a | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.5±0.4 |

| 1/2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.7±0.6 | 0.5±0.6 |

| PO/IP | 18.8 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 11.4 | 7.2 | 22.1 | 13.2 | 15.3±6.1 | 7.6±4.4 |

| Posterior parietal cortex | 3.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4±1.5 | 1.4±1.6 |

Labeling that was found outside ICMS defined forelimb representation of PMv, but still most likely part of other representations in PMv was excluded from the present analysis, thus explaining total percentages below 100%. CMA: cingulate motor area; FR: Frontal area rostral to PMv; AO: Anterior operculum; PO/IP: Posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex

As the main effect of area was significant, further post-hoc analysis of multiple comparisons was conducted. In general, the cortical areas connected with the PMv distal forelimb area could be clustered into three groups (Group 1, 2 and 3) based on the magnitude of connections.

Major connections (Group 1)

First, the highest magnitude of connections was with M1 (25.8% of cell bodies and 29.5% of terminals). In general, BDA labeling in M1 was located in the rostrolateral part of the M1 forelimb area to a much greater degree than its caudomedial part (25.6% of cell bodies, 28.0% of terminals located in rostrolateral M1; Figure 6). In the caudal aspect of M1, BDA labeling of cell bodies and terminals occupied the lateral aspect of the distal forelimb representation. In progressively more rostral portions of M1, cell bodies and terminals occupied both the medial and lateral aspects of the distal forelimb representation. The labeling distribution extended outside of the distal forelimb representation into proximal representations of M1 and somewhat beyond the physiologically defined area. This pattern left the caudomedial aspect of the M1 forelimb area largely unlabeled. In general the cell bodies and terminals were interspersed in the same locations.

Figure 6. Co-registration of the M1 distal forelimb representation and cell body and terminal distribution.

Co-registration of the M1 distal forelimb representation (red area) to cell body distribution. When co-registered with the physiological map of M1, BDA-labeled cell bodies and voxels with labeled terminals were shown to be almost exclusively located in the lateral portion of the M1 distal forelimb map in its caudal aspect and more medially in its more rostral aspect (rostro-lateral pattern), thus leaving the caudo-medial portion of M1 largely unlabeled. Distribution of labeling extended somewhat outside the mapped forelimb representation. In order to determine assignment of BDA labeled cells/terminals located in unmapped areas to appropriate cortical regions, an analysis was performed on ICMS mapping data derived from nine naïve animals used in previous experiments in our laboratory. These animals underwent more extensive mapping in the cortical regions surrounding M1 (medially and laterally) and throughout the PMd region (rostral to M1). From these maps, it was possible to determine a mean distance from the center of the M1 distal forelimb representation to physiological regions of interest surrounding M1 along multiple vectors. The PMd distal forelimb representation was determined to begin ~1.2 mm rostral to the edge of the M1 distal forelimb representation (corresponding to the most rostral pink line). A 95% confidence interval (CI) for the position of the PMd distal forelimb area was calculated and used to define the limit of the M1 forelimb region (most caudal pink line). Label found caudal to the CI was considered to be in M1 and rostral to the CI was considered to be in PMd. Similar calculations were performed for other regions of interest around M1. In general, the physiologically-defined areas surrounding M1 that were mapped in the present experiment corresponded closely to the statistically-based borders derived from vector measurements. Injection core is indicated by the black area surrounded by the brown contour. Terminal area indicated by black dots. Cell bodies are indicated by larger brown dots. Red = distal forelimb area; Blue = proximal representation; M=Medial; R=Rostral; Scale bar = 1mm.

Additionally, in all cases, considerable BDA labeling was observed in areas immediately rostral and rostro-lateral to the PMv distal forelimb representation in an area that we have designated as a frontal rostral area, or area FR (22.7 % of cell bodies; 22.3% of terminals). The difference between the magnitude of connections of each of the two Group 1 areas (M1rl and frontal area rostral to PMv) and each of the other regions in the ipsilateral hemisphere was statistically significant (Fisher’s Protected Least Significant Difference; p<0.05). There was no significant difference between these two regions. Thus, these two connections are considered to be major. In the post-hoc analyses, as the interactive effects (cells bodies versus terminals) were non-significant, the results reflect significant differences in connectivity regardless of the direction of the connection.

Moderate connections (Group 2)

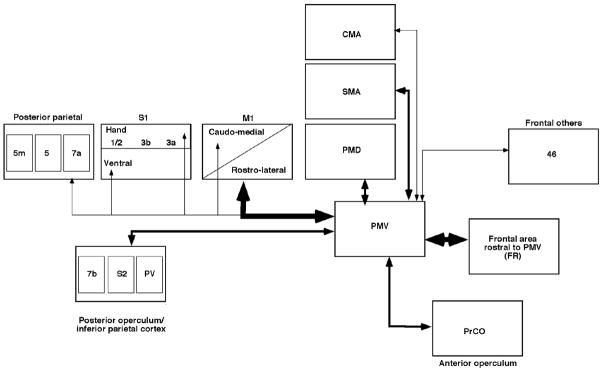

Four areas contained significantly fewer connections than areas in Group 1, but significantly more connections than each of the S1 hand areas (3a, 3b, 1/2). Connections of the PMv distal forelimb area with this second group are considered to be moderate. Group 2 included the posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex (PO/IP; 7.6% of terminals), SMA (7.5% of terminals), the anterior operculum (7.1% of terminals) and PMd (5.8% of terminals).

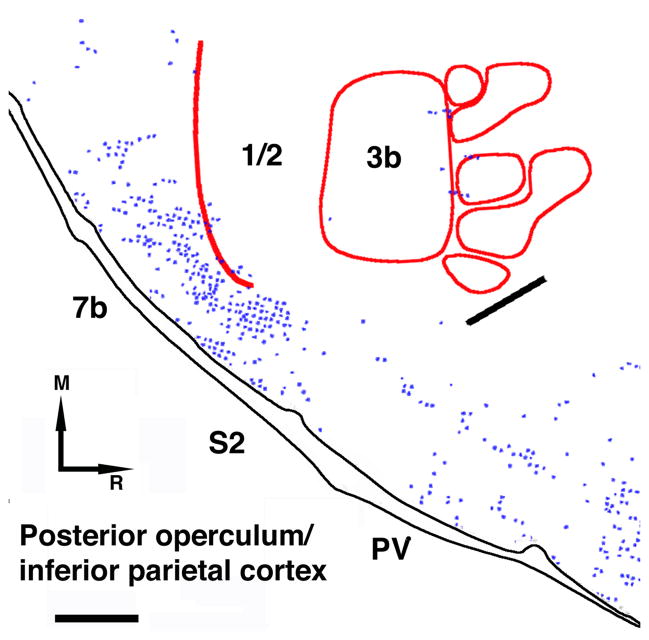

The collective area designated as the PO/IP could not be identified with precision, but a very similar pattern of cell body and terminal labeling was found in each of the cases, and was similar to previous reports. BDA-labeled cell bodies and terminals were principally found in the cortex lying on the upper and lower banks of the lateral sulcus in areas caudal to the hand/face septum. A large number of labeled cell bodies and terminals could also be observed more rostrally along the medial lip of the lateral sulcus. Identification of these non-primary somatosensory areas (corresponding to areas 5, 7, S2, PV) was primarily based on topographic location, myeloarchitecture (Figure 7), and previous neurophysiological and cytoarchitectonic maps in platyrrhine monkeys (Guldin et al., 1992; Jain et al., 2001; Qi et al., 2002). Though not statistically significant, it is interesting to note that, in three of the four cases, the posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex area contained more cell bodies than terminals (mean cell bodies = 15.3%; terminals = 7.6%).

Figure 7. Identification of somatosensory areas based on myelin staining.

A: Example of myelin staining (Case 1934). Myelin sections were used to identify the structural borders of area 3b in all cases. A thicker line of lighter myelin staining separates the hand and face areas (hand-face septum; large black arrow). The hand-face septum was observable in several sections in every case. A thin line of lighter myelin staining, separating the individual digit zones, was also observable in 3b (small black arrowheads). Oral representations are also visible lateral and rostral to the hand representation (small white arrowheads). Thin white arrows show the borders of S2 and PV. M=Medial; R=Rostral. B: Topographic map as suggested by myeloarchitecture. Digits are represented from D1 laterally to D5 medially. Identification of facial (F1-F3) and oral (O1-O4) representations were based on Jain and collaborators (Jain et al., 2001). Scale bar = 1mm

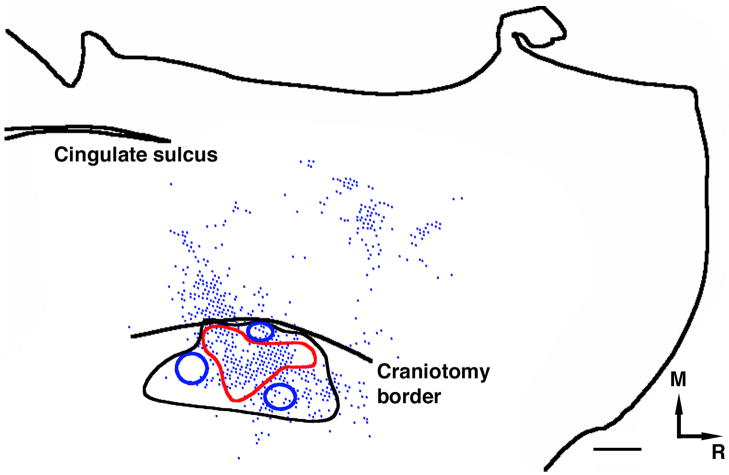

A dense cluster of cell bodies and terminals was observed near the medial convexity, an area corresponding to SMA. Superposition of the neurophysiological data to the reconstruction of cell body and terminal labeling (aided by blood vessel locations) in case 1892 allowed us to confidently associate the cluster of PMV connections with the SMA distal forelimb representation defined by ICMS-evoked movements (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Co-registration of neurophysiologically defined SMA distal forelimb representation map with terminal distribution.

In case 1892 (large injection), additional ICMS mapping was conducted near the medial convexity to locate the SMA distal forelimb representation. The medial extent of the SMA distal forelimb representation was limited by the craniotomy border. Red contour shows the extent of the observed digit sites. These were surrounded by proximal representations (elbow and shoulder) shown by blue contours and unresponsive sites (black contour). In this figure, co-registration of the physiological map with the labeled voxels shows that the majority of terminal labeling was near the medial convexity and corresponds to the SMA forelimb representation and to a large extent, to the distal forelimb representation. Additional, sparser labeling was observed along the medial wall, which we attributed to the cingulate motor areas. M=Medial; R=Rostral. Scale bar = 1mm.

A large number of BDA-labeled cell bodies and terminals were also found in the anterior operculum. The anterior operculum was defined as the cortex lying on the upper and lower banks of the lateral sulcus in areas rostral to the hand/face septum.

Most of the labeling attributed to PMd was located at ~1–1.5mm rostral from the M1 distal forelimb representation border, where the PMd distal forelimb representation is typically found (see Figure 6).

Minor connections (Group 3)

Third, the remaining areas contained significantly fewer connections than areas with major or moderate connections. The numbers of cell bodies and terminals in these areas were very low and did not differ significantly from one another. These included S1 ventral (2.9% of terminals), CMA (2.6% of terminals), other frontal areas (1.6% of terminals), M1cm (1.5% of terminals), posterior parietal cortex (1.4% of terminals), area 3a (0.5% of terminals), area 1/2 hand (0.5% of terminals) and area 3b hand (0.3% of terminals). Connections of PMv with Group 3 areas are considered to be relatively minor.

Relatively few labeled terminals were observed in the hand representations of areas 3a, 3b or 1/2. Figure 9 depicts the typical location of labeled terminals in relation to the neurophysiologically defined hand representation. The largest number of labeled terminals in S1 was found in case 1892. Particularly in that case, labeled terminals were located ventral to the 3b hand representation. Labeling located ventral to the identified S1 hand area was included in the S1 ventral area, and was separate from more ventral areas within the posterior operculum/inferior parietal area (see below). Based on its topographic location and neurophysiological maps in previous studies (Jain et al., 2001), as well as in other animals in our laboratory (unpublished observations), it is likely that these connections are located within the S1 oro-facial area. Additional labeling was observed in areas caudal to S1 and caudo-medial to the posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex (particularly in 9409) in the posterior parietal cortex.

Figure 9. Co-registration of the neurophysiologically defined 3b hand representation with terminal distribution.

For each case, the neurophysiological map of S1 receptive fields and/or the myelin stained sections were co-registered with the distribution of terminal labeling. As in M1, the location of blood vessels allowed precise co-registration of the physiological and anatomical data. The locations of terminals are shown in relation to the 3b hand representation (approximate depth: 1500μm). Caudally, a red line is drawn beyond which no responses could be driven by cutaneous or proprioceptive stimulation, presumably corresponding to the caudal border of S1. The thick black line represents the location of the hand-face septum. Clusters of labeled terminals were typically located several millimeters caudal to the 3b hand representation. These terminals were found outside the S1 hand representation, within the posterior operculum/inferior parietal area, where area 7b is found most caudally and S2/PV more rostrally. Scale bar = 1mm.

In cases where the medial wall was well preserved (1934, 1892, 3024), labeled cell bodies and terminals were observed in areas corresponding to CMA. All labeling located ventral (i.e., on the medial wall) to the cluster corresponding to SMA was attributed to the CMA.

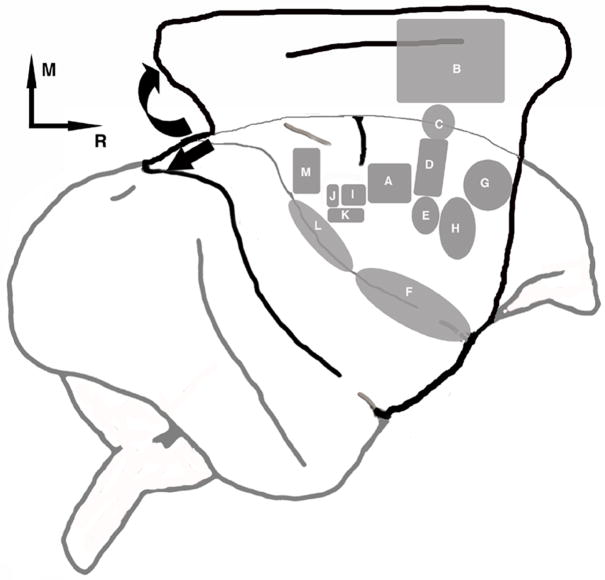

Finally, additional sparse labeling was observed in more medial areas of the frontal cortex, in an area designated other frontal areas. Figure 10 depicts the location of all cortical areas we identified that have connections with PMv.

Figure 10. Unfolding of the cortical surface and approximate location of functional areas.

Cartoon illustrating the process of unfolding of the cortical surface used in the present experiment. Approximate location of 14 functional areas will be referred to A) M1; B) CMA; C) SMA; D) PMd; E) PMv; F) anterior operculum; G) other frontal areas; H) frontal area rostral to PMv (FR); I) 3b hand; J) 1/2 hand; K) S1 ventral; L) posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex; M) posterior parietal cortex.

Discussion

In the present experiments, we defined the pattern of intracortical connections of the PMv distal forelimb representation in a New World primate, the squirrel monkey. While the qualitative results generally agreed with previous findings in other species, we found that the PMv distal forelimb representation has dense interconnections with the rostral and lateral aspects of the M1 distal forelimb area, but not the caudal and medial aspects. In addition the PMv distal forelimb representation has substantial reciprocal connections with a frontal cortical region located rostral to PMv, designated here as area FR. To our knowledge, connections with this area have not been described previously. Finally, the close association of cell bodies and terminals indicates that connections with PMv are reciprocal throughout the hemisphere. These data are consistent with the notion that PMv functions as a key node in the neural network that controls forelimb movements.

Methodological limitations

Before discussing the present results and their implications for the role of PMv in motor control, it is important to comment on three technical limitations that may have affected the results. First, the method used to document PMv terminals (number of voxels with ≥ 2 terminal boutons) was chosen to provide an accurate and detailed report of their distribution in a reasonable amount of time. Thus, our quantitative report of the magnitude of PMv projections to different areas does not reflect the density of the projections per se, but rather, the number of voxels containing at least two terminals. By converting both terminal and cell body estimates to percentages of total values in the entire hemisphere, it is possible to compare quantitatively the relative magnitude of afferent and efferent projections for each of the cortical regions of interest. It is noteworthy that the percentage of terminals was not significantly different from the percentage of cell bodies in any of the cortical regions, strengthening the validity of this approach.

Second, the identification of functional areas that were located outside of the neurophysiologically- and neurohistochemically-defined borders was limited. Tangential sectioning provided a reliable means to identify the distribution of PMv connections with respect to functional and anatomical areas, especially in M1, S1 and SMA. In addition, reasonably precise identification of PMd was based on statistically defined estimates of representational boundaries derived from previous experiments in this laboratory. More precise localization of labeling with other cortical regions will require additional approaches to determine the association. Thus, to the extent that the definition of borders in these additional areas was not ideal, and was primarily based upon topographic location and similarities to results of previous tract-tracing studies, the conclusions regarding these areas should be considered tentative.

Finally, while we used BDA (10,000 MW) in the present study to maximize visualization of terminal boutons, it is not known to be a particularly effective retrograde neuronal tracer (Reiner et al., 2000). The counts obtained with BDA (10,000MW) cannot be considered as a complete representation of the numbers of cells projecting to the zone of injection. Thus, we do not rely on the absolute numbers, but instead compare the proportion of retrogradely labeled cells in each area with the proportion of anterogradely labeled terminals in the same areas. In this regard, the proportions are comparable. Thus, while this tracer provides an incomplete picture of retrograde connections, the distribution, at least between cortical areas, appears to be a representative sample. Only direct comparisons of numbers using multiple tracers, and examining distribution as a function of soma size, cortical lamina, etc. will completely resolve this issue.

Reciprocity of PMv connections with ipsilateral cortical regions

The present results clearly demonstrate the reciprocity of PMv connections in each of the cortical regions. Whereas reciprocity of PMv cortical connectivity is not a novel concept (Matelli et al., 1986), to our knowledge it had not been quantitatively supported to such an extent previously. Reciprocity might provide the anatomical substrate for feedforward/feedback circuits or ‘looping’ between cortical areas. The importance of the reciprocity found in the present study underlines the interdependence of cortical areas sharing connections. This view radically contrasts to linear cortical connectivity, which is often used to portray cortical flow for motor production proceeding from prefrontal, premotor and finally primary motor cortex (for example see Kandel et al., 1991, 3rd edition p. 826). The only possible exception to the rule was the posterior opercular/inferior parietal area. Whereas not significantly different, the percentage of labeled cell bodies in this area was about twice the percentage of labeled terminals.

Because of the close correspondence between the magnitude of cell body and terminal labeling in most instances, and the lack of a significant label type by area interaction, the remaining discussion will simply refer to connections of the PMv distal forelimb representation.

Major corticocortical connections of the PMv distal forelimb area

The quantification procedure allowed us to determine significant differences in the magnitude of connections among the various regions in the ipsilateral hemisphere (Figure 11). This resulted in identification of two regions sharing major connections with PMV: the M1 forelimb area, and area FR located rostral to PMv. These areas contained significantly more connections than any of the other regions.

Figure 11. Pattern of PMV connections emerging from the present study.

Pattern of PMV connections resulting from the present set of experiments. All ipsilateral connections were found to be reciprocal. Thickness of arrows reflects the relative quantity of terminal connections in various cortical areas (major, moderate and minor connections respectively).

PMv connections with the M1 forelimb area

The M1 distal forelimb area and its adjacent M1 proximal representation collectively contained the greatest number of connections with the PMv distal forelimb area of all 14 regions studied. These connections comprise nearly 30% of the corticocortical connections of PMv. This major connection with M1 is well-known, and has been identified in virtually every study examining connections of PMv (Godschalk et al., 1984; Matelli et al., 1986; Ghosh et al., 1987; Kurata, 1991; Stepniewska et al., 1993; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995; Dum and Strick, 2005). The present data provide the first detailed description of a segregated pattern of connections between the M1 and PMv distal forelimb areas. Both labeled cell bodies and terminals were found almost exclusively in the rostro-lateral aspect of the M1 distal forelimb area. After relatively small injections of BDA limited to the neurophysiologically-identified distal forelimb area of PMv, the caudo-medial aspect of the M1 distal forelimb area was almost completely devoid of label. Interestingly, our report closely replicates the pattern described by Matelli and collaborators (1986) for one macaque monkey in which a small injection was made in PMv. Terminals were distributed in a medio-lateral direction from the superior precentral dimple to the M1 distal forelimb field. More recently, Dum and Strick (2005) have reported that the caudalmost portion of the M1 digit representation in another platyrrhine monkey, the cebus monkey, “does not project densely to” the digit representation of PMv.

The departure from the typical pattern of labeling throughout the M1 distal forelimb area reported in the majority of previous studies most likely resulted from at least four factors. First, the association of the neurophysiological data with the patterns of connectivity allowed us to determine the location of the intracortical terminals and cell bodies with precision. Second, whereas other studies have derived neurophysiological maps of the frontal areas (Matelli et al., 1986; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995), to date, few studies systematically mapped the entire PMv and M1 forelimb representations at a resolution high enough to distinguish boundaries so precisely (but see Dum and Strick, 2005). The physiological maps we derived allowed identification of both the injection site and the topographic properties of the M1 forelimb area connected with PMv. Additionally, the use of a species with a relatively unconvoluted frontal cortex, combined with tangential sectioning allowed us to more accurately display the distribution of terminals and cell bodies relative to the entire M1 distal forelimb map. Third, the use of the sensitive anterograde tracer, BDA (10,000MW), optimized the terminal labeling. Fourth, the volume of injections in the present study was relatively small, and confined to a portion of the neurophysiologically identified distal forelimb representation of PMv. It is possible that another portion of the PMv distal forelimb area that was not injected with tracer is interconnected with caudo-medial M1.

The segregation of PMv connections in the rostro-lateral forelimb area of M1 raises important questions concerning the functional role of the M1cm and M1rl subdivisions. To date, no differences in cytoarchitecture, suggesting different functional roles has been identified in the caudo-medial versus rostro-lateral M1 distal forelimb area. Previous studies have documented differences in caudal vs. rostral subdivisions of the M1 distal forelimb area based on differential somatosensory inputs and somatosensory response properties (Strick and Preston, 1982b; Strick and Preston, 1982a) or lesion-induced deficits (Martin and Ghez, 1991; Martin et al., 1993; Friel et al., 2005). But studies of neuronal activity in awake, behaving monkeys have not differentiated functional differences between caudo-medial versus rostro-lateral neurons. Yet, based on the differential pattern of connections that these areas have with PMv, it is tempting to suggest that they would be involved in different functions for motor control of the forelimb.

The role of the powerful connection between M1 and PMv was recently investigated in detail (Shimazu et al., 2004). In macaques, while stimulation of PMv alone (F5) produces relatively little contralateral EMG activity (Cerri et al., 2003), it can facilitate corticospinal outputs from M1 to arm and distal forelimb motoneurons in the spinal cord. Thus, as suggested by Shimazu, et al. (2004) it is possible that PMv can alter the gain of corticospinal outputs from M1 specifically during visually guided movements of the hand. It is significant that projections from the PMv distal forelimb area are divergent, terminating within both distal and proximal representations of M1. Such divergence may be necessary to facilitate corticospinal outputs to the entire complement of distal and proximal muscles involved in reach.

Connections with frontal area rostral to PMv

The second major connection of the PMv distal forelimb area, accounting for over 22% of PMv intracortical connections, is with a frontal region rostral to PMv designated here as area FR, or frontal rostral area. The relationship of labeled cell bodies and terminals in this region with those observed in previous studies is not completely clear, as no studies have yet provided neurophysiological and tract-tracing data in sufficient detail in the same animals in order to draw precise conclusions. This is particularly problematic since the location of frontal areas based solely on the identification of the inferior arcuate dimple in squirrel monkeys is quite variable (Huerta et al., 1987). Additionally, because of differences in cytoarchitectonic and physiological criteria used to delineate these regions, some disagreement still exists regarding the functional designations of regions connected with premotor cortex (e.g., see (Dum and Strick, 1991; Stanton et al., 1993). However, it appears that the connections observed in the present study have not been described previously.

Area FR might represent a previously unrecognized premotor forelimb area in squirrel monkeys. Whereas this area was not electrophysiologically identified in the animals used in present study, subsequent experiments in our laboratory have demonstrated that ICMS in this region evokes forelimb movements at relatively high current levels (17–80μA; average = 48.1μA; Dancause, unpublished data). These forelimb sites were clearly segregated from the PMv distal forelimb area as defined in the present study. If confirmed, these results would suggest that area FR corresponds to an additional premotor field involved in forelimb control. Other investigators have also suggested that an additional forelimb representation exists in premotor cortex of macaque monkeys with comparable connectivity patterns (Luppino, G., personal communication). At least in squirrel monkeys, as the magnitude of PMv connections with this separate forelimb area is equivalent to that of M1, further investigation of this region and its similarities to premotor subdivisions in other non-human primates is warranted.

Several reasons may account for the lack of reports in the literature of PMv connections with this region rostral to PMv. Potentially, the small size of our injections, the use of BDA (which is known to produce confined injection cores) and the physiological localization of the injection core (i.e., confining the injection to the distal forelimb area, specifically avoiding the face representation) could have allowed better visualization of this pathway. It is also possible that the use of tangential sectioning made this pattern particularly clear in our study.

As it has often been suggested in the past that PMv plays a role in eye-hand coordination (Godschalk et al., 1981; Rizzolatti et al., 1983; Kurata and Tanji, 1986; Gentilucci et al., 1988; Rizzolatti et al., 1988; Gentilucci et al., 1989; Mushiake et al., 1991), one might suspect that PMv would have connections with frontal visuomotor areas, such as area 8. But based upon studies to date, there appears to be little support for this idea (Arikuni et al., 1988; Stanton et al., 1993). For example, in New World monkeys, Tian and Lynch (Tian and Lynch, 1996) physiologically identified FEF in cebus monkeys and concluded that it does not have connections with the topographically identified area of the postarcuate cortex corresponding to PMv.

Moderate corticocortical connections of the PMv distal forelimb area

Four connections with the PMv distal forelimb area were considered moderate. These included connections with SMA, PMd, the anterior operculum and the posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex (Preuss and Goldman-Rakic, 1989). Connections with SMA are well-known from a number of previous studies (Matelli et al., 1986; Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Kurata, 1991; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995). The area designated as posterior operculum/inferior parietal cortex likely included PV and more caudally, areas S2 (Krubitzer and Kaas, 1990; Krubitzer and Kaas, 1992) and 7b/AIP (Padberg et al., 2005). Connections between PMv with areas 7b/AIP, S2 and PV have been reported previously (Matelli et al., 1986; Kurata, 1991; Luppino et al., 1999; Lewis and Van Essen, 2000; Tanné-Gariepy et al., 2002; Wu and Kaas, 2003).

Based on our quantitative criteria, connections between PMv and PMd in squirrel monkeys are considered to be moderate. Connectivity between PMv and PMd has been confirmed in recent studies (Luppino et al., 2003; Tachibana et al., 2004; Dum and Strick, 2005). Dum and Strick (2005) have reported substantial connections between the PMv and PMd digit representations in cebus monkeys, with PMd ranking third in magnitude behind M1 and SMA. In the present study, PMd ranked sixth in magnitude, but was statistically indistinguishable from SMA, PO/IP, and the frontal operculum. It should be noted that the ranking in Dum and Strick study was confined to the areas of the frontal cortex, which also contributes to PMd being ranked higher. PMd as described in the present study was defined largely on statistical estimates of borders based on our previous experience in mapping the M1/PMd region. By measuring the distance from the M1 distal forelimb area to the PMd distal forelimb border in these previous cases, we were able to define a 95% confidence interval for the expected PMd border in the present cases (see Figure 6).

The anterior operculum connections with PMv have also been described previously (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995). The principal area within this region that has been reported to connect with PMv is PrCO (Dum and Strick, 2005).

Minor corticocortical connections of the PMv distal forelimb area (Figure 11; thin arrows)

Several additional cortical areas have reciprocal connections with the PMv distal forelimb area, but these connections are considered to be minor based on the magnitude of cell body and terminal labeling. These included M1cm, CMA, area 3a, area 3b (hand), area 1/2 (hand), S1 ventral, posterior parietal cortex and other frontal areas.

Few studies have performed quantitative analysis of the magnitude of connections between PMv and CMA. In Old World monkeys, inputs from CMA have been reported to be considerably larger (Ghosh and Gattera, 1995; 11.9 % of ipsilateral connections) than what we found. More recent studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of PMv connections with CMA in cebus monkeys is also smaller than in macaques (Dum and Strick, 2005; 6.2% of frontal connections). Thus, it is possible that quantitative differences exist between Old and New World monkeys in the connectivity of CMA and PMv distal forelimb areas.

Our results clearly show that PMv shares few connections with S1. Particularly, very few and inconsistent connections were found with S1 hand representations. Connections with S1 have been described in other studies in which, however, the identification of these fields was not as detailed as in the present study (Godschalk et al., 1984; Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Ghosh and Gattera, 1995; Cipolloni and Pandya, 1999; Tanné-Gariepy et al., 2002). Based on the caudal boundaries of the M1 distal forelimb area as defined by ICMS (maximum current = 30μA), we found that PMv has very few connections with area 3a. We thus suggest that most of the PMv connections previously described with area 3a (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Kurata, 1991) are actually located within the caudo-lateral aspects of M1.

While the magnitude of total connections with S1 is low, it is interesting to note that a larger number of labeled cell bodies and terminals was found in the area ventral to the neurophysiologically and neurohistologically identified S1 hand area (S1 ventral area), i.e., in the S1 face area. Thus, it appears that most of the connections that have been reported between S1 and PMv are associated with the S1 face representation. It is well documented that PMV also shares connections with orbitofrontal areas (Benjamin and Burton, 1968; Scott et al., 1986; Morecraft et al., 1992; Carmichael and Price, 1995; Cipolloni and Pandya, 1999; Cavada et al., 2000; contained in anterior operculum category in the present paper) which are also connected to face representations in lateral aspects of S1. Thus, the pattern of intracortical connections of PMv suggests that it may be part of a broad and important network involved in oro-facial and forelimb motor control that can be associated with unimanual feeding (Wise, In press-b).

Finally, we found connections with other frontal areas several millimeters rostral to the PMv distal forelimb representation, i.e., substantially more rostral and medial than area FR. Based on the topographic location of these connections, we propose that they are located in area 46. Connections with PMv and a comparable region have been reported in other studies (Dum and Strick, 2005; Barbas 1987; Ghosh 95).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kelsey D. Needham and Katherine A Brennan for help in the production of anatomical data, Robert Cross for his help in preparation and assistance during surgical procedures.

Numa Dancause is supported by a fellowship from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for which he is greatly thankful. Randolph Nudo is supported by NIH grant NS30853 and a Bugher Award from the American Heart Association. This work was also supported by NICHD Center Grant HD02528 and by the Landon Center on Aging.

- AIP

anterior intraparietal area

- CMA

cingulate motor areas

- FEF

frontal eye fields

- FR

frontal area rostral to PMv

- FV

frontal ventral (visual) area

- M1

primary motor cortex

- PMd

dorsal premotor cortex

- PMv

ventral premotor cortex

- PO/IP

posterior operculum/inferior parietal area

- PrCO

precentral opercular area

- PV

parietal ventral area

- S2

second somatosensory area

- SMA

supplementary motor area

- VIP

ventral intraparietal area

Footnotes

Whereas in several studies in macaque monkeys, PMv has been subdivided further into a caudal and rostral portion (caudal PMv or F4 and rostral PMv or F5), these subdivisions, as well as subdivisions of other premotor areas such as the supplementary motor area (SMA) and the dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), have not yet been identified in squirrel monkeys. Thus, the collective terms “PMv”, “SMA” and “PMd” are used.

Literature cited

- Arikuni T, Watanabe K, Kubota K. Connections of area 8 with area 6 in the brain of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1988;277(1):21–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.902770103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Pandya DN. Architecture and frontal cortical connections of the premotor cortex (area 6) in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256(2):211–228. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbay S, Peden EK, Falchook G, Nudo RJ. Sensitivity of neurons in somatosensory cortex (S1) to cutaneous stimulation of the hindlimb immediately following a sciatic nerve crush. Somatosens Mot Res. 1999;16(2):103–114. doi: 10.1080/08990229970546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin RM, Burton H. Projection of taste nerve afferents to anterior opercular-insular cortex in squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) Brain Res. 1968;7(2):221–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Sensory and premotor connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363(4):642–664. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz-Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso-Suarez F. The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(3):220–242. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerri G, Shimazu H, Maier MA, Lemon RN. Facilitation from ventral premotor cortex of primary motor cortex outputs to macaque hand muscles. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(2):832–842. doi: 10.1152/jn.01026.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolloni PB, Pandya DN. Cortical connections of the frontoparietal opercular areas in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403(4):431–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum RP, Strick PL. Premotor areas: Nodal points for parallel efferent systems involved in the central control of movement. In: Humphrey DR, Freund H-J, editors. Motor Control: Concepts and Issues. London: Wiley; 1991. pp. 383–397. [Google Scholar]

- Dum RP, Strick PL. Frontal lobe inputs to the digit representations of the motor areas on the lateral surface of the hemisphere. J Neurosci. 2005;25(6):1375–1386. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3902-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel KM, Barbay S, Frost SB, Plautz EJ, Hutchinson DM, Stowe AM, Dancause N, Zoubina EV, Quaney BM, Nudo RJ. Dissociation of sensorimotor deficits after rostral versus caudal lesions in the primary motor cortex hand representation. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(2):1312–1324. doi: 10.1152/jn.01251.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallyas F. Silver staining of myelin by means of physical development. Neurol Res. 1979;1(2):203–209. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1979.11739553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci M, Fogassi L, Luppino G, Matelli M, Camarda R, Rizzolatti G. Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. I. Somatotopy and the control of proximal movements. Exp Brain Res. 1988;71(3):475–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00248741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci M, Fogassi L, Luppino G, Matelli M, Camarda R, Rizzolatti G. Somatotopic representation in inferior area 6 of the macaque monkey. Brain Behav Evol. 1989;33(2–3):118–121. doi: 10.1159/000115912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Brinkman C, Porter R. A quantitative study of the distribution of neurons projecting to the precentral motor cortex in the monkey (M. fascicularis) J Comp Neurol. 1987;259(3):424–444. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Gattera R. A comparison of the ipsilateral cortical projections to the dorsal and ventral subdivisions of the macaque premotor cortex. Somatosens Mot Res. 1995;12(3–4):359–378. doi: 10.3109/08990229509093668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk M, Lemon RN, Kuypers HG, Ronday HK. Cortical afferents and efferents of monkey postarcuate area: an anatomical and electrophysiological study. Exp Brain Res. 1984;56(3):410–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00237982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk M, Lemon RN, Nijs HG, Kuypers HG. Behaviour of neurons in monkey peri-arcuate and precentral cortex before and during visually guided arm and hand movements. Exp Brain Res. 1981;44(1):113–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00238755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould HJ, 3rd, Cusick CG, Pons TP, Kaas JH. The relationship of corpus callosum connections to electrical stimulation maps of motor, supplementary motor, and the frontal eye fields in owl monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1986;247(3):297–325. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould HJ, 3rd, Kaas JH. The distribution of commissural terminations in somatosensory areas I and II of the grey squirrel. J Comp Neurol. 1981;196(3):489–504. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldin WO, Akbarian S, Grusser OJ. Cortico-cortical connections and cytoarchitectonics of the primate vestibular cortex: a study in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) J Comp Neurol. 1992;326(3):375–401. doi: 10.1002/cne.903260306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. Frontal eye field as defined by intracortical microstimulation in squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and macaque monkeys. II. Cortical connections. J Comp Neurol. 1987;265(3):332–361. doi: 10.1002/cne.902650304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Catania KC, Kaas JH. A histologically visible representation of the fingers and palm in primate area 3b and its immutability following long-term deafferentations. Cereb Cortex. 1998;8(3):227–236. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Qi HX, Catania KC, Kaas JH. Anatomic correlates of the face and oral cavity representations in the somatosensory cortical area 3b of monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429(3):455–468. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010115)429:3<455::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The functional organization of somatosensory cortex in primates. Anat Anz. 1993;175(6):509–518. doi: 10.1016/s0940-9602(11)80212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. Evolution of somatosensory and motor cortex in primates. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;281A(1):1148–1156. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Nelson RJ, Sur M, Lin CS, Merzenich MM. Multiple representations of the body within the primary somatosensory cortex of primates. Science. 1979;204(4392):521–523. doi: 10.1126/science.107591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. East Norwalk, CONN: Appleton & Lange; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. The organization and connections of somatosensory cortex in marmosets. J Neurosci. 1990;10(3):952–974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00952.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. The somatosensory thalamus of monkeys: cortical connections and a redefinition of nuclei in marmosets. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319(1):123–140. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K. Corticocortical inputs to the dorsal and ventral aspects of the premotor cortex of macaque monkeys. Neurosci Res. 1991;12(1):263–280. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(91)90116-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K, Tanji J. Premotor cortex neurons in macaques: activity before distal and proximal forelimb movements. J Neurosci. 1986;6(2):403–411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00403.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428(1):112–137. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Martin JH. Postnatal development of differential projections from the caudal and rostral motor cortex subregions. Exp Brain Res. 2000;134(2):187–198. doi: 10.1007/s002210000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Murata A, Govoni P, Matelli M. Largely segregated parietofrontal connections linking rostral intraparietal cortex (areas AIP and VIP) and the ventral premotor cortex (areas F5 and F4) Exp Brain Res. 1999;128(1–2):181–187. doi: 10.1007/s002210050833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Rozzi S, Calzavara R, Matelli M. Prefrontal and agranular cingulate projections to the dorsal premotor areas F2 and F7 in the macaque monkey. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17(3):559–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH, Cooper SE, Ghez C. Differential effects of local inactivation within motor cortex and red nucleus on performance of an elbow task in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94(3):418–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH, Ghez C. Impairments in reaching during reversible inactivation of the distal forelimb representation of the motor cortex in the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1991;133(1):61–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90057-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JW, Donoghue JP, Sanes JN. Direction control in humans with motor cortex lesion. Neurosci Abst. 1991;(17):308. [Google Scholar]

- Matelli M, Camarda R, Glickstein M, Rizzolatti G. Afferent and efferent projections of the inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1986;251(3):281–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.902510302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecraft RJ, Geula C, Mesulam MM. Cytoarchitecture and neural afferents of orbitofrontal cortex in the brain of the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323(3):341–358. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushiake H, Inase M, Tanji J. Neuronal activity in the primate premotor, supplementary, and precentral motor cortex during visually guided and internally determined sequential movements. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66(3):705–718. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ. Remodeling of cortical motor representations after stroke: implications for recovery from brain damage. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2(3):188–191. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ, Friel KM, Delia SW. Role of sensory deficits in motor impairments after injury to primary motor cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(5):733–742. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ, Jenkins WM, Merzenich MM, Prejean T, Grenda R. Neurophysiological correlates of hand preference in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci. 1992;12(8):2918–2947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-02918.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]