Abstract

A hospital-based, case-control study was used to describe clinical and laboratory findings in 83 dogs diagnosed with noninfectious, nonerosive, immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA) in western Canada. Case medical records were reviewed. Cases were analyzed as total IMPA cases and as subgroups [breed, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), reactive, and idiopathic] and compared with the general canine hospital population. Dogs with IMPA differed in age (P = 0.004) and weight (P = 0.01) from other hospital admissions. Idiopathic IMPA cases were older (4–10 y; P < 0.05), compared with the general canine hospital population, and their common laboratory abnormalities included the following: leukocytosis, nonregenerative anemia, increased alkaline phosphatase, and hypoalbuminemia. The SLE cases were seen more often in summer and fall (P = 0.04), raising concern of an undiagnosed etiologic agent. The hock joint appeared to be the most reliable for diagnosis of IMPA, and arthrocentesis of both hock joints may aid in case identification.

Résumé

Polyarthrite canine à médiation immunitaire : observations cliniques et résultats de laboratoire dans 83 cas répertoriés dans l’ouest du Canada (1991–2001). Une étude a été réalisée à partir des dossiers d’un hôpital dans le but de décrire les observations cliniques et les résultats de laboratoires chez 83 chiens ayant reçu un diagnostic de polyarthrite à médiation immunitaire (PAMI), non infectieuse et non érosive, dans l’ouest du Canada. Les cas ont été analysés dans leur ensemble et en sous-groupes [race, lupus érythémateux systémique (LES), réactifs et idiopathiques] et comparés à la population canine générale de l’hôpital. Les chiens atteints de PAMI différaient en âge (P = 0,004) et en poids (P = 0,01) des autres admissions à l’hôpital. Les cas idiopathiques de PAMI étaient plus âgés (4–10 a; P < 0,05) comparés à la population canine générale de l’hôpital et les anomalies de laboratoire comprenait : leucocytose, anémie non régénérative, phosphatase alcaline augmentée et hypoalbuminémie. Les cas de LES étaient plus nombreux en été qu’en automne (P = 0,04), soulevant la possibilité d’un agent étiologique indéterminé. L’articulation du jarret semblait être la plus fiable pour le diagnostic de la PAMI et l’arthrocentèse des 2 articulations pourrait aider pour l’identification des cas.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Introduction

Joint disease is common in all ages and breeds of dogs. Disorders affecting the joints can generally be classified as either inflammatory or noninflammatory. Noninflammatory joint disease that results from poor conformation, trauma, or developmental disorders is correctly termed degenerative joint disease. Inflammatory joint disease, termed arthritis, can be subdivided, based on its cause (infectious versus noninfectious) and its radiographic/histologic characteristics (erosive versus nonerosive). Immune-mediated (noninfectious) nonerosive polyarthritis (IMPA) is the most common polyarticular disease in dogs (1,2). This condition is believed to be a result of immune-complex deposition within the synovium, resulting in a sterile synovitis (1,3). Reported clinical signs are variable and may include reluctance to walk, stiffness, lameness, and joint swelling. Systemic signs may be absent or include pyrexia, inappetence, and multisystemic disease [dermatitis, hemolytic anemia (3–7)]. Occasionally, only systemic signs are observed (8,9).

One classification scheme for nonerosive polyarthropathies is the type I–IV system, as outlined in Table 1 and utilized in other studies (2,10). Immune-mediated nonerosive polyarthritis may also be classified as 1) a breed-associated syndrome, 2) associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 3) occurring secondary to a distant immunogenic stimulus (reactive), or 4) idiopathic. Breed-associated polyarthritis syndromes, in which a genetic basis is postulated to cause the sterile synovitis due to immune complex deposition, have been identified in the Akita (11), boxer, weimaraner, Bernese mountain dog (12), German shorthaired pointer, spaniel, and beagle breeds (3,4). Some of these dogs may exhibit concurrent signs of meningeal inflammation (8). Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic immune-mediated disease, reported infrequently in the dog, in which polyarthritis is the most commonly associated clinical abnormality. Diagnosis requires documentation of multisystemic involvement, elimination of underlying infectious disease, and positive serologic tests [antinuclear antibody or lupus erythematosus cell preparation (Table 2; 13, 14)]. Reactive nonseptic synovitis/polyarthritis has been reported in association with a variety of antigenic stimuli. Antigenic stimuli implicated include the following: 1) infective or inflammatory processes remote from the joints, such as bacterial endocarditis, pyometra, pleuritis, diskospondylitis, chronic salmonellosis, heartworm disease, urinary tract infection, and severe periodontitis (7,15,16); 2) neoplasia remote from the joints (4,5); 3) hepatic or gastrointestinal disease, such as chronic bacterial diarrhea, ulcerative colitis, and inflammatory bowel disease (4,17); 4) drug–induced effects in association with recent administration of sulfadiazine-trimethoprim (18), penicillins, erythromycin, lincomycin, cephalosporins, and phenobarbital (3); and 5) recent vaccination (5,6,10). Cases of IMPA in which none of these conditions or antigenic stimuli are identified are classified as idiopathic. This final subclassification is thought to be the most common form of IMPA and is the least understood.

Table 1.

Classification of nonerosive polyarthropathiesa

| Type I (idiopathic) — no identifiable associated disease |

| Type II (reactive) — associated with an infectious or inflammatory disease distant from the joint |

| Type III (enteropathic) — associated with gastrointestinal or hepatic disease |

| Type IV (neoplastic) — associated with neoplasia remote from the joints |

Modified from Bennett (5)

Table 2.

| Major signs | Minor signs | Serologic evaluation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Definite SLE — Two major signs with a positive serologic test; 1 major sign, 2 minor signs with a positive serologic test

Probable SLE — One major sign with a positive serologic test; 2 major signs with a negative serologic test

To date, relatively few studies have examined canine IMPA (2,5,8,10,14,19,20). The purpose of this retrospective study was to describe the clinical and laboratory findings for dogs diagnosed with IMPA in western Canada in order to provide greater insight into the condition.

Materials and methods

The veterinary teaching hospital (VTH) at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) serves as a referral hospital for the geographic area, in addition to having a well-established primary care caseload. Medical records of dogs diagnosed with polyarthritis at the VTH between 1991 and 2001 were reviewed by 1 of the authors (JWS). An IMPA case was defined as a dog diagnosed with noninfectious, nonerosive, immune-mediated polyarthritis based on cytologic evidence of suppurative inflammation in the synovial fluid of ≥ 2 joints and failure to identify an infectious cause or neoplastic condition directly involving the joints. Synovial fluid samples were considered to have suppurative inflammation, using the accepted definition, if nucleated cell counts were > 2 nucleated cells/high power field (< 2 cells/50× objective lens is considered to be normal or low cellularity) and neutrophil counts were > 10% to 12% of nucleated cells present within the fluid (2,10). Samples were also considered to be diagnostic for suppurative inflammation if neutrophils represented > 10% to 12% of the inflammatory cells in samples with normal nucleated cell counts, provided that another joint in the same dog met the criteria previously mentioned. Dogs were not considered to be IMPA cases if intra- or extracellular bacteria were noted in the synovial fluid samples, if the joint fluid culture was positive for organisms, or if blood contamination prevented a clear diagnosis. All cytologic findings were reviewed by the Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS), Saskatoon. Specific diagnostic tests performed by the primary clinician at the time of the initial presentation varied on a case basis. Additional diagnostic tests included a complete blood (cell) count (CBC), a serum biochemical panel, urinalysis, radiographs (chest, abdomen, joints), abdominal ultrasonography, echocardiography, cultures [blood, urine, joint synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and transtracheal wash fluid], serum antibody titers against infectious agents (serologic testing for the presence of infectious agents), cytologic examination (transtracheal wash fluid and CSF), serum antinuclear antibody [ANA by an indirect immunoperoxidase method with bovine kidney being used as the substrate, with goat sera and goat anti dog immunoglobulin (Ig)G], serum rheumatoid factor, urine protein:creatinine ratio (UP:C), serum bile acids, and tissue/organ biopsies.

Data obtained from all case records included signalment, date of presentation, history, clinical signs, findings on physical examination, results from diagnostic tests, specific joints utilized for arthrocentesis versus those diagnostic for IMPA, and diagnosis. Data obtained from medical records, when reported, included vaccine history, treatment, and outcome. Cases were classified as 1) breed-associated IMPA, 2) SLE, 3) reactive IMPA, or 4) idiopathic IMPA (Table 3). The diagnosis of SLE was made by using established criteria (Table 2). All IMPA cases that were concurrently diagnosed with a disease that may have had an immunogenic stimulus for the development of IMPA were grouped as “reactive” for analysis. The “reactive” category was further defined and the dogs classified as 1) infective or inflammatory with processes found remote from the joints, only if supportive microbial culture and histologic or cytologic evidence was present, 2) neoplastic, if processes remote from the joints were noted, 3) gastrointestinal or hepatic, if histologic gastrointestinal or hepatic lesions were noted or if infectious organisms were isolated from these sites on culture, or 4) drug associated or vaccine related, if a drug or vaccine was associated with onset of clinical signs [provided it was given before clinical signs developed, provided that clinical signs occurred within 30 d of administration (if known), and provided that no alternate cause of polyarthritis was found]. Dogs were classified as idiopathic IMPA cases if no underlying disease process was identified.

Table 3.

Diagnosis, classification, and frequency of cases diagnosed with canine immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA) (1991–2001)

| Classification | Diagnosis | Number of cases |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive IMPA | Eosinophilic gastritis | 1 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 1 | |

| Meningitis, parvo-enteritis | 1 | |

| Multisystemic inflammatory disease [uveitis, immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA), IBD] | 1 | |

| Meningitis, bacterial diskospondylitis | 1 | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 2 | |

| Bacterial pneumonia, pancreatitis | 1 | |

| Pancreatitis | 2 | |

| Immune nodular panniculitis, bacterial cystitis | 1 | |

| Bacterial cystitis | 2 | |

| Hepatic lipidosis, lymphocytic-plasmacytic hepatitis | 1 | |

| Bacterial osteomyelitis | 1 | |

| Periocular cellulitis | 1 | |

| Myocarditis (suspected), glomerulonephritis | 1 | |

| Neosporosis | 1 | |

| Idiopathic IMPA | IMPA | 37 |

| Epiglossitis, tonsillitis, gingivitis | 1 | |

| Steroid responsive meningitis | 5 | |

| Breed-associated IMPA | IMPA [Akita (1), Bernese mountain dog (3)] | 4 |

| Steroid responsive meningitis (weimaraner) | 1 | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (probable/definitive) | IMPA | 12 |

| IMPA, polymyositis | 2 | |

| IMPA, pyoderma | 3 |

Statistical analyses

Analysis focused on 5 groups: 1) total IMPA (consisting of all cases), and the subgroups: 2) breed associated IMPA, 3) SLE, 4) reactive IMPA, and 5) idiopathic IMPA. All canine patients admitted to the WCVM during the 11-year period were identified from the hospital database for comparison (63 430 non-case visits from 23 661 canine patients). Data available for all non-cases (age, gender, spay/neuter status, date of presentation) and for a subset of the non-cases (weight) were extracted. Descriptive statistics were calculated on the IMPA cases. Subsequent statistical analyses were completed to determine if cases differed from other hospital admissions by signalment or pattern of presentation over time.

All signalment and time of admission variables were divided into biologically relevant categories: reproductive status, gender [male (reference category), female], age [≤ 1 y, 2–3 y (reference category), 4–6 y, 7–10 y, > 10 y], weight [< 10 kg (22 lb), 10–20 kg (22–44 lb; reference category), 21–30 kg (45–66 lb), 31–40 kg (67–88 lb), > 40 kg (88 lb), missing], season [Jan–Mar, Apr–Jun, Jul–Sep (reference category), Oct–Dec], and year (1991 to 2001).

Comparisons between 4 of the 5 IMPA groups (total IMPA and subgroups SLE, reactive IMPA, and idiopathic IMPA) and routine hospital admissions were analyzed by using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to account for repeated hospital visits by individual dogs. Breed-associated IMPA was not examined, using statistical models, due to the low number of cases identified in the records. A separate analysis was completed for each of the 4 IMPA groups previously mentioned to examine the relative difference in the occurrence of risk factors between cases of IMPA in that group and data from the hospital-based control population. The outcome or dependent variable in the model for each type of IMPA was case or control status (1 or 0).

Data were analyzed by using a commercial software program [SAS version 8.2 for Windows (PROC GENMOD); SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA]. Model specifications included a binomial distribution, logit link function, and a repeated statement with subject equal to dog identification. The variables gender, age, weight, season of admission, and year of admission were individually examined sequentially, using unconditional logistic regression, as described previously, to determine if there were detectable differences between cases and other dogs admitted to the hospital. Individual dog breed was not included in the analysis due to the small number of cases in each breed.

All independent variables with P > 0.25 in the unconditional or univariable assessments were considered in developing final multivariable models for the case-control comparison for each type of IMPA. Risk factors were defined as confounders, if removing or adding the factor changed the effect estimate for the exposure by more than 10%, and the factor was retained in the final model. Biologically reasonable interactions were assessed between significant risk factors (P < 0.05) in the final model. Variables remaining in the final multivariable model at P < 0.05, based on the robust empirical standard errors produced by the GEE analysis, were considered statistically significant. Interactions that were not statistically significant were not reported.

Results

Total immune-mediated polyarthritis

Eighty-three different dogs, accounting for a total of 544 hospital visits, diagnosed with IMPA were extracted from the 11-year period, providing a cumulative incidence of 0.35% (cumulative incidence was derived as number of cases divided by total number of canine patients admitted to the VTH during the 11-year period). Forty-five breeds/crosses were represented, with the Labrador retriever (11%), German shepherd (8%), and American Eskimo (6%) being the most common. Weight was a significant determinant of whether a dog had IMPA (P = 0.01). After accounting for age, dogs that weighed < 10 kg were more likely [odds ratio (OR): 2.3; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.0 to 5.0; P = 0.04] to be diagnosed with IMPA than dogs that weighed 21 to 30 kg.

Male and female dogs were presented in equal proportions (51% and 49%, respectively), with female spayed dogs being reported most frequently (35%), followed by male castrated, male intact, and female intact (28%, 23%, 14%, respectively). Overall, gender was not a risk factor for IMPA, whether it was considered simply as male to female (P= 0.30) or whether spay/neuter status was considered in addition to gender (P = 0.06) in models adjusting for age and weight. However, spayed females were more likely than intact females to be diagnosed with IMPA after accounting for weight and age (OR: 3.0; 95% CI: 1.3 to 7.3; P = 0.01).

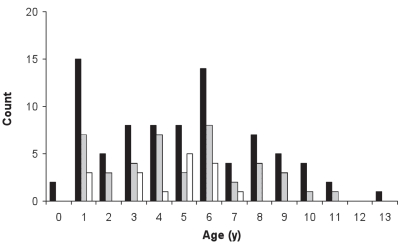

Cases ranged in age from 0.2 to 13.4 y, with a mean of 4.9 y [standard deviation (s) = 3.1 y; Figure 1]. Age was a significant risk factor for IMPA after accounting for weight (P = 0.004). Dogs aged 4–6 y (OR: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.5 to 7.7; P = 0.003) and dogs aged 7–10 y (OR: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.8 to 6.6; P = 0.0002) were more likely to have IMPA than dogs aged ≤ 1 y.

Figure 1.

Age at presentation for canine cases diagnosed (1991–2001) with immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA; black solid bars), idiopathic IMPA (grey solid bars), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; clear solid bars).

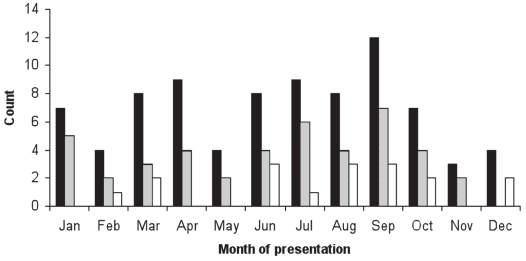

While the number of dogs with IMPA was highest in September (Figure 2), there was no significant seasonal trend for IMPA admissions when compared with other hospital admissions across the study years (P = 0.80). Eight dogs (10% of IMPA cases) were tested for antibody titers against infectious agents. There was no significant difference in the annual frequency of admissions for IMPA from 1991 to 2001 (P = 0.08).

Figure 2.

Month of presentation for canine cases diagnosed (1991–2001) with immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA; black solid bars), idiopathic IMPA (grey solid bars), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; clear solid bars).

Breed-associated immune-mediated polyarthritis

During the 11-year period, 5 dogs were diagnosed with breed-associated IMPA. The Akita (1-year-old castrated male), Bernese mountain dog (1.4 and 0.9-year-old intact females, 2.7-year-old intact male), and weimaraner (0.9-year-old intact male) breeds were represented. Clinical signs and examination findings included lameness (n = 4), temperature ≥ 39.6°C (103.3°F) (n = 2), bloody diarrhea (n = 1), and neck pain (n = 1, diagnosed with steroid responsive meningitis). Results from blood and urine analyses were unremarkable, with the exception of a leukocytosis [white blood cells (WBC) > 17.1 × 109/L; reference interval: 6.0–17.1 × 109/L] and decreased serum albumin (< 28 g/L; reference interval: 28 to 38 g/L) in 1 dog, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase (> 90 U/L; reference interval: 9 to 90 U/L) in another dog. Results from ANA testing were available for 2 dogs and were negative.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

During the 11-year period, 17 dogs, comprising 12 breeds/crosses, fulfilled the criteria for SLE (cumulative incidence of 0.07%). Three dogs fulfilled the criteria for definitive SLE [polyarthritis, positive ANA, and leukopenia (n = 1) or polymyositis via muscle biopsy (n= 2)]. The remaining 14 dogs met the criteria for probable SLE [polyarthritis and positive ANA (n = 13) or skin lesions (n = 1)]. The German shepherd (24%) was the breed most commonly represented. Weight was not a significant risk factor with SLE (P = 0.13).

Males and females were equally likely (47% versus 53%) to be diagnosed with SLE, with spayed females being reported most frequently (41%), followed by castrated males, intact males, and intact females (29%, 18%, 12%, respectively). Gender was not a risk factor for SLE (P = 0.17). The mean age at presentation was 4.2 y (range 0.7 to 6.8; s= 2.0 y). There was no significant difference in the age of cases presented with SLE as compared with other hospital presentations during the study (P = 0.07).

There was a significant seasonal pattern to SLE admissions (P = 0.04). The SLE cases were more likely to be seen, relative to other hospital admissions, from July to September (OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.4 to 3.8; P = 0.001) and October to December (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.3 to 3.4; P = 0.001) than from January to March.

Common observations reported by owners when presenting their dog included lethargy (n = 2), stiffness (n = 5), lameness (n = 5), and difficulty in walking/standing (n = 3). Vomiting was noted in the history of 2 dogs (12%). Over 50% (9/17) of the dogs were either febrile (temperature ≥ 39.6°C) at time of presentation or had a history of being febrile by the local/referring veterinarian.

The majority of the cases (15/17; 88%) were subject to a CBC, biochemical panel, and urinalysis; all cases were subject to at least a CBC. Biochemical panel results were considered abnormal in 7 dogs (47%) in which a panel was performed; the most common abnormalities were an increase in serum alkaline phosphatase [> 90 U/L; reference interval: 9 to 90 U/L, 27% (4/15)], and a decreased serum albumin [< 28 g/L; reference interval: 28–38 g/L, 27% (4/15)]. The most common abnormality observed on the CBC was a nonregenerative anemia [hematocrit (Hct) ≤ 37 L/L; range: 37 to 55 L/L] occurring in 29% (5/17) of the dogs (mean Hct for anemic dogs was 31 L/L; range: 26 to 36 L/L). A urinalysis was completed in 94% (16/17) of the individuals. Eleven of these patients had some degree of proteinuria; however, only 2 exceeded 0.3 g/L (reference < 0.5 g/L), with protein contents of 0.6 and 1.0 g/L (Table 4). A urine protein:creatinine ratio was performed on the individual with a urine protein content of 1.0 g/L (UP:C = 1.2). Serum antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers were preformed on 16/17 of the SLE cases and ranged from 1:160 to 1:40 960, with 50% (8/16) 1:1280 or greater.

Table 4.

Urine specific gravity, protein content, and urine protein:creatinine ratio (UP:C)a from urinalyses performed on 69 canine patients diagnosed with immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA)

| Protein (g/L)b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine specific gravity | None | < 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 5.0 | Total |

| 1.008–1.012 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1.013–1.030 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4f | 2d | 14 |

| > 1.030 | 1 | 23g | 8 | 1 | 1e | 1c | 35 |

| Not listed | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 20 | 29 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 69 |

UP:C values provided when available (with IMPA subclass classification)

The conversion for proteinuria (trace = < 0.3 g/L, 1+ = 0.3 g/L, 2+ = 1.0 g/L, 3+ = 5g/L) was used when necessary

UP:C of 7.0 (reactive)

UP:C of 1.5 (reactive); 0.7 (idiopathic)

UP:C of 1.2 (probable SLE)

UP:C for 3 cases all < 0.7 (all idiopathic)

UP:C of 2.4 for 1 case (idiopathic)

Reactive immune-mediated nonerosive polyarthritis

Eighteen IMPA cases were grouped as reactive, based on the identification of a concurrent immunogenic stimulus for the development of IMPA. The German shepherd (11%) and American Eskimo (11%) were the breeds most commonly represented; however, there was no significant difference (P= 0.08) between the reactive group and the general WCVM canine population with respect to weight.

More females than males (67% versus 33%) had reactive IMPA; however, the difference was not statistically significant when compared with that for other hospital admissions (P= 0.32). Spayed females accounted for the largest percentage (49%), followed by intact females, castrated males, and intact males (17% for each). The mean age at presentation was 6.7 y (range 0.2 to 13.4; s = 4.0 y). Age was not a significant risk factor for reactive IMPA (P = 0.45). There was no seasonal variation (P = 0.31) in admissions for reactive IMPA or difference in the frequency of admissions across study years (P = 0.11).

The types of stimuli implicated in reactive cases included infective or inflammatory processes that were found remote from the joints: parvovirus infection and meningitis (n = 1), meningitis and bacterial diskospondylitis (n = 1), pancreatitis and bacterial pneumonia (n= 1), nodular panniculitis and bacterial cystitis (n = 1), bacterial osteomyelitis (n = 1), peri-ocular cellulitis (n= 1), glomerulonephritis (n= 1), Neospora sp. infection (n = 1), bacterial pneumonia (n = 2), pancreatitis (n = 2), and bacterial cystitis (n = 2). Gastrointestinal or hepatic disease was confirmed in 4 dogs, based on histopathologic findings: eosinophilic gastritis (n = 1), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 1), inflammatory bowel disease with concurrent uveitis (n = 1), and lymphocytic-plasmacytic hepatitis and hepatic lipidosis (n = 1; same dog).

Idiopathic, nonerosive immune-mediated polyarthritis

Forty-three cases, comprising 31 breeds/crosses were classified as idiopathic (cumulative incidence = 0.18%). The Labrador retriever (14%) and American Eskimo (7%) were the breeds most commonly represented. Males were more likely than females (56% verses 44%) to have idiopathic IMPA, although this difference was not significant when compared with the general canine population. Spayed females accounted for the largest percentage (35%), followed by castrated males, intact males, and intact females (33%, 23%, 9%, respectively). Gender (P = 0.73) and weight (P = 0.27) were not associated with the risk of idiopathic IMPA.

The mean age at presentation was 4.8 y (range 0.6–11.5; s = 2.8 y). Age at presentation was a significant risk factor for idiopathic IMPA (P = 0.03). Dogs that were 4 to 6 y and 7 to 10 y were more likely to be diagnosed with IMPA than were dogs that were either ≤ 1 y (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.0 to 6.4; P = 0.04 and OR: 3.4; 95% CI: 1.7 to 6.7; P = 0.0005) or 2 to 3 y (OR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0 to 4.9; P = 0.05 and OR: 2.9; 95% CI: 1.5 to 5.8; P = 0.002), respectively.

Forty-nine percent of the dogs were presented between June and September; however, there was no significant seasonal trend when compared with other hospital presentations (P = 0.36). There was also no difference in the frequency of presentation for idiopathic IMPA across the study years (P = 0.17)

Clinical signs commonly reported by owners when presenting their dog included lethargy (n =12), lameness (n = 15), difficulty walking/standing (n = 3), stiffness (n = 4), and inappetence (n = 3). Vomiting, diarrhea, or both were noted in the history of 4% of the individuals. Over 50% (24/43) of the dogs either were febrile at time of presentation (40%), had a history of being febrile by the local/referring veterinarian (7%), or were both (9%). The majority (14/21; 67%) of the dogs that were febrile on presentation had an elevated temperature ≥ 40°C. Vaccine history was poorly documented; however, 2 dogs had been vaccinated against distemper virus-adenovirus 2-parvovirus-parainfluenza virus prior to the onset of clinical signs. Neither record clearly defined the time of vaccination further than “several weeks” prior to presentation. Four dogs had received antibiotics (including enrofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and amoxicillin) from their referring veterinarian prior to presentation at the VTH; however, since clinical signs were present prior to the drug being administered, the dogs were not included within the reactive group. Recent corticosteroid administration was not noted in the history of patients from this group.

The diagnostic procedures varied considerably with each individual; however, in the majority of cases (31/43; 72%) a CBC, biochemical panel, and urinalysis had been performed. In 91% (39/43) of cases, at least a CBC had been performed. The most common abnormalities observed on the CBC were a leukocytosis (WBC > 17.1 × 109/L; reference interval: 6.0 to 17.1 × 109/L,), occurring in 16/39 (41%) of the dogs, and nonregenerative anemia, occurring in 7/39 (18%) of the dogs (mean Hct for anemic dogs was 33 L/L; range: 27 to 37 L/L). Results from biochemical analyses were considered abnormal in 22/34 (65%) of those in which they were performed. The most common abnormalities were an increase in serum alkaline phosphatase (> 90 U/L; reference interval: 9 to 90 U/L) and a decreased serum albumin (< 28 g/L; reference interval: 28 to 38 g/L) in 47% and 32% of the individuals, respectively. A urinalysis was completed in 81% (35/43) of the individuals. Twenty-six (74%) of these patients had some degree of proteinuria; however, only 5 of these exceeded 0.3 g/L; reference: < 0.5 g/L; UP:Cs were run on 4 of these individuals and were all ≤ 0.7 (reference: < 0.5). Other diagnostic tests performed included synovial fluid culture (58%), thoracic, abdominal, and joint radiographs (56%, 54%, 21%, respectively), urine culture (49%), ANA titer (all negative; 7%), and titers for infectious disease (all negative; 7%). Joint radiographs appeared normal or revealed soft tissue swelling with no erosive changes.

Treatment varied with each animal; however, the majority (35, 81%) were discharged on an immunosuppressive drug; prednisone (Apo-Prednisone; Apotex, Toronto, Ontario) (n = 25), prednisone and azathioprine (Gen-Azathioprine; Genpharm, Toronto, Ontario) (n = 9), and prednisone and amoxicillin (Amoxil; Pfizer Canada, Kirkland, Quebec) (n = 1). Treatment was not listed for 5 animals. Given poor follow-up records on most of the cases, it was difficult to determine response to treatment.

Arthrocentesis

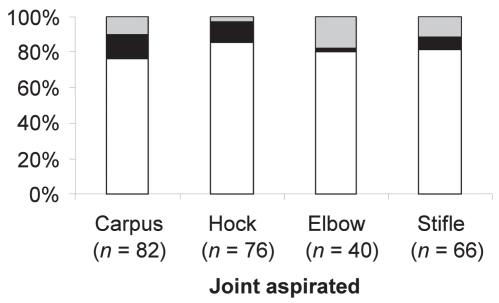

The joints used for arthrocentesis and those yielding results that were diagnostic for IMPA were compared. The carpus was the joint most commonly used for arthrocentesis (82 cases), followed by the hock (76 cases), stifle (66 cases), elbow (40 cases), and shoulder (2 cases). A diagnosis of IMPA was most likely [overall: 74/76 (97%)] obtained from arthrocentesis of the hock joint. When the hock joint was aspirated bilaterally, all cases were correctly identified on at least 1 aspirate; 44/53 (83%) joints were positive bilaterally, and 9/53 (17%) were positive unilaterally. Reliability decreased when other joints were utilized [overall: carpus (90.2%), stifle (89.4%), elbow (82.5%); Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Joints yielding synovial fluid samples cytologically suggestive of immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA) in 83 canine patients diagnosed with IMPA (1991–2001). Diagnostic for IMPA on all aspirates (clear solid bars); aspirated bilaterally, but diagnostic for IMPA only unilaterally (black solid bars); not diagnostic for IMPA (grey solid bars).

Discussion

We retrospectively studied a group of dogs diagnosed with nonerosive noninfectious IMPA, classified the dogs into appropriate groups, and examined potential risk factors. We specifically wanted to examine dogs in the prairie provinces of western Canada, because it is an area that is currently assumed to be virtually free of infectious tick-borne disease. Our study identified several unique risk factors and laboratory findings for canine IMPA and subgroups, thus providing greater insight into this uncommon condition.

Reports of previous studies have suggested that young to middle-aged, medium/large-breed dogs are most often affected with IMPA (2,5,7,20). In this study, middle to older-aged dogs (4–10 y) were at increased risk of IMPA. Furthermore, smaller dogs (< 10 kg) were more likely to have IMPA than larger dogs (21–30 kg). As reported for previous studies (2,7,10), we did not observe a gender predisposition, while we did note several commonly diagnosed breeds (Labrador retriever, German shepherd, and American Eskimo) (1,3,4). As reported for a recent study (2), IMPA cases were predominately idiopathic (52%), with smaller proportions assigned to breed-associated (6%), SLE (20%), and reactive (22%) subgroups.

Reactive IMPA is thought to occur when immune complexes develop secondary to infection, inflammation, or other stimuli at a distant site. Although reactive disease is commonly discussed in the literature, few studies have specifically examined this condition (5,15). We observed a diverse group of possible stimuli theoretically associated with the production of a suppurative, nonseptic polyarthritis, including both infectious and inflammatory. Although not commonly reported in previous studies, we found several cases of IMPA that were secondary to gastrointestinal disease. Polyarthropathy consequent to gastrointestinal disease has been reported in humans (17). Since the vast majority of dogs diagnosed with IMPA did not undergo intestinal or hepatic biopsies, it is possible that the enterohepatic group is under-represented. Unfortunately, it is impossible to confirm that any of the stimuli previously mentioned resulted in IMPA, or if these dogs truly had idiopathic IMPA and concurrent lesions. None of the dogs in this study appeared to have developed IMPA secondary to drugs or neoplasia. Two dogs developed IMPA within several weeks of vaccination, but the association with vaccination was unclear due to poor records, lack of follow-up, and unknown recovery time, so these dogs were included within the idiopathic group.

Medium and large sporting breeds have been reported as being more often affected by idiopathic IMPA (1,3,5,7). Our findings differed from those of previous studies, as idiopathic IMPA was most frequently diagnosed in middle to older aged dogs, without gender or weight predisposition (1–3,5,7,10,15). However, we did note that several breeds, specifically the Labrador retriever and American Eskimo may be predisposed, as has been previously suggested (1).

As noted previously (2,3,5,7,10), we found that many patients with idiopathic IMPA have a history of lethargy, lameness, difficulty in walking/standing, stiffness, inappetence, vomiting, or diarrhea. In addition, a large percentage of the individuals are, or have a history of being, febrile (50%), often pronounced (≥ 40°C; 2,3,5,7,10). This finding highlights the importance of arthrocentesis as a diagnostic procedure in dogs with fever of undetermined origin, many of which may not have swollen or painful joints (9). Indeed, 1 study found that most dogs with polyarthritis did not have overt joint pain, and lameness was observed in fewer than one-third of affected dogs (20). In a previous study at the WCVM, concurrent steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis (SRMA) was found in some dogs with both IMPA and spinal pain (8); most of these dogs did not have swollen joints or signs of lameness. The spinal pain elicited in IMPA patients may originate from the meninges or meningeal vasculature, the intervertebral facetal joints, or both (8). These findings emphasize the importance of a thorough and complete history and physical examination, including orthopedic examination, which may aid in making a diagnosis of IMPA (and possible concurrent SRMA) earlier in the diagnostic process.

Nonregenerative anemia, leukocytosis, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and hypoalbuminemia predictably occur with IMPA, as noted in other studies (2,5,10,15,20). In several cases, these abnormalities were severe (Hct = 27 L/L); however, for the majority of cases, their deviation from the reference range was mild. As noted by previous authors, hematologic findings are most likely due to chronic inflammation (2,9,10,20). Elevated alkaline phosphatase was likely secondary to endogenous glucocorticoid release (as none of the dogs were receiving corticosteroids prior to analysis) or, possibly, cholestasis. Hypoalbuminemia could be secondary to either acute phase inflammatory response or proteinuria, though few dogs showed significant proteinuria. No specific findings were noted on radiographs of joints, thorax or abdomen, abdominal ultrasonographs, or cultures of synovial fluid. Despite this, we recommend that these diagnostic procedures be carried out as part of the complete assessment of IMPA cases in order to exclude concurrent or causative infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic disease.

Unfortunately, SLE remains a diagnosis fraught with individual interpretation, disagreement, and clinician bias. In an attempt to determine whether the dogs with IMPA in our study were affected by SLE, we adhered strictly to the accepted criteria (13,21) and found that 20% of IMPA cases were classified as having SLE, with most (14 of 17) being categorized as probable SLE. Findings in previous studies vary widely in the proportion of IMPA cases diagnosed with SLE (8% to 46%) (2,15). In this study, the inclusion of many cases in the SLE category hinged on a positive ANA titer, as all cases had been diagnosed with polyarthritis in order to be included in the study. Positive ANA titers have been noted in the serum of normal dogs and dogs with diseases other than SLE; conversely, negative titers have been recorded in dogs diagnosed with SLE (2,6,10,22–24). Clearly, improved criteria for the diagnosis of SLE are needed and some authors refer to dogs with a positive ANA titer and polyarthritis as having an SLE-like syndrome. In our study, only 39% of dogs placed into the total IMPA group had been diagnostically evaluated with an ANA titer. It is possible that had titers been run on all cases, several might have been categorized differently.

As previously reported (14,23), we did not find significant gender, weight, or age predispositions to the SLE subgroup. The German shepherd breed accounted for 24% of the cases, yet for only 7% of the total WCVM canine population. A severe and progressive form of SLE has previously been documented in this breed (25). As established in prior studies, animals were often febrile and showed clinical signs of polyarthritis (difficulty in walking/standing). Nonregenerative anemia, leukocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia occurred in similar frequencies to those previously reported (7,14,15,23). Moderate proteinuria (> 0.5 g/L) is often noted in patients with SLE. This is an important clinical finding, as the presence of glomerulonephritis is 1 of the major diagnostic criteria. As such, it is especially helpful in making a diagnosis of SLE and important for prognosis (23). We noted moderate proteinuria in only 2 of the probable SLE cases; however, without an UP:C (which was performed in only 1 of the individuals) the degree of proteinuria is subjective, dependent on urine specific gravity and other variables (urine pH, occult blood).

To our knowledge, seasonal trends have not previously been documented for SLE or IMPA. In fact, a lack of seasonal distribution has been reported in another study (2). Classically, seasonal patterns are associated with infectious or allergic-based disease. A temporal relationship with tick infestation, infection, and clinical onset of disease has been established for many canine tick-borne disorders, with signs of clinical illness occurring typically 1 wk to 6 mo postinfection, depending on the causative agent (26,27). Cases of canine polyarthritis associated with ehrlichiosis, borreliosis, leishmaniasis, and rickettsiosis have been reported (3,7) and an Ehrlichia sp. has been documented as a cause of canine meningo-encephalitis/polyarthritis in some dogs (28). In a recent study, a possible association between seropositivity for antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, and IMPA was found (2). Research from the central northern United States reveals that the greatest canine tick infestation occurs in the summer and late fall (29), with onset of tick-borne disease occurring in the fall (30). This seasonality is consistent with our findings for the SLE group.

The tick-borne diseases, including Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis, have not been documented in dogs confined to western Canada (specifically Alberta and Saskatchewan). Although surveys of these tick-borne diseases have not been completed recently in this geographic area, their occurrence is believed to be very low. In our study, few individuals diagnosed with IMPA were tested for antibodies against infectious agents, making it difficult to access this potentially important source of antigenic stimuli. Systemic lupus erythematosus and idiopathic IMPA are diseases of exclusion and, as such, our noted seasonal trend within the SLE group may warrant further investigation.

The carpus, stifle, and hock are reported to be the most commonly affected joints in IMPA (3,6,7,20). We found that arthrocentesis of the hock joint was the most useful in obtaining a diagnosis of IMPA. The remaining joints (elbow, carpus, stifle) were fairly similar in their reliability of obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Based on these findings, if IMPA is suspected, we recommend arthrocentesis of the hock joints and at least 1 other joint (carpus, stifle, or elbow). It is imperative that arthrocentesis is performed bilaterally, in order to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Given the retrospective nature of this study, data for vaccine history, treatment, and outcome were not available for all IMPA cases, and all cases did not undergo the same diagnostic testing. This shortcoming does not allow for an evaluation of treatment or response and may have limited our ability to accurately group cases. Our criteria for inclusion in this study did not include joint radiographs, which were completed in 28% of the total IMPA patients and 21% of the idiopathic IMPA cases. Although we cannot rule-out erosive articular disease from our dataset, it is rare in dogs, and affected animals often develop progressive articular deformities, including luxations and subluxations (31–33), which would be detectable on physical examination. None of these changes were documented in our records. In another study of suppurative, nonseptic canine polyarthropathies, erosive changes were observed in 3% of dogs that had joint radiographs performed (2). We feel that joint radiographs should be recommended in the diagnostic work-up of IMPA; they are especially important in cases that do not respond well to therapy, as supportive radiographic evidence is progressive by nature.

Idiopathic IMPA is a diagnosis of exclusion; as such, a thorough work-up is integral to diagnosis. It is possible that several of our cases classified as idiopathic would have been categorized differently had further testing been completed. As noted earlier, this is especially true for cases of SLE and reactive IMPA. Since cases were analyzed retrospectively over a period of 11 y, there was poor consistency in medical therapy, and information regarding specific treatment, therapy response, or follow-up was lacking.

Canine IMPA remains a poorly understood and diagnostically challenging condition within the veterinary community. Maintaining a heightened level of suspicion in dogs matching the criteria previously described will aid in obtaining an accurate diagnosis in these challenging cases. Clearly, further analysis and improved classification of this disease is necessary. Future investigation of the seasonal trend noted in a proportion of the cases is indicated and may lead to the discovery of previously overlooked antigenic stimuli occurring in western Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan M. Taylor, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, and Sherry Myers, Prairie Diagnostic Services, for their editorial suggestions. CVJ

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Stull was responsible for the review of cases, compilation of the data, and the bulk of the paper. Dr. Evason was responsible for the major drafting and revision of the paper. Dr. Carr was responsible for editorial suggestions and provided extensive input to the discussion. Dr. Waldner was mainly responsible for the statistical analyses.

References

- 1.Magne M. Swollen joints and lameness. In: Ettinger JE, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rondeau MP, Walton RM, Bissett S, et al. Suppurative, nonseptic polyarthropathy in dogs. J Vet Int Med. 2005;19:654–662. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19[654:snpid]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor SM. Disorders of the joints. In: Nelson RW, Couto CG, editors. Small Animal Internal Medicine. 2. Philadelphia: Mosby; 1998. pp. 1076–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett D. Treatment of the immune-based inflammatory arthropathies of the dog and cat. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 1188–1196. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett D. Immune-based non-erosive inflammatory joint disease of the dog. 3. Canine idiopathic polyarthritis. J Small Anim Pract. 1987;28:909–928. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michels GM, Carr AP. Noninfectious nonerosive arthritis in dogs. Vet Med. 1997;92:798–803. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen NC, Morgan JP, Vasseur PB. Joint diseases of dogs and cats. In: Ettinger JE, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 1862–1886. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb AA, Taylor SM, Muir GD. Steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis in dogs with noninfectious, nonerosive, idiopathic, immune-mediated polyarthritis. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:269–273. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2002)016<0269:smidwn>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn KJ, Dunn JK. Diagnostic investigations in 101 dogs with pyrexia of unknown origin. J Small Anim Pract. 1998;39:574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1998.tb03711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements DN, Gear RN, Tattersal J, et al. Type I immune mediated polyarthritis in dogs: 39 cases (1997–2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:1323–1327. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty SA, Center SA, Shaw EE, et al. Juvenile-onset polyarthritis syndrome in Akitas. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;198:849–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meric SM, Child G, Higgins RJ. Necrotizing vasculitis of the spinal pachyleptomeningeal arteries in three Bernese mountain dog littermates. J Anim An Hosp Assoc. 1986;22:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks SL, Henry CJ. CVT update: Diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 514–516. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett D. Immune-based non-erosive inflammatory joint disease of the dog. 1. Canine systemic lupus erythematosus. J Small Anim Pract. 1987;28:871–889. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen NC, Weisner K, Castles JJ, et al. Noninfectious canine arthritis: The inflammatory arthritides. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976;169:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvert CA, Greene CE. Bacteremia in dogs: Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1986;8:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orchard TR, Wordsworth BP, Jewell DP. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: Their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998;42:387–391. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giger U, Werner LL, Millichamp NJ, et al. Sulfadiazine-induced allergy in six Doberman Pinschers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:479–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett D, Kelly DF. Immune-based non-erosive inflammatory joint disease of the dog. 2. Polyarthritis/polymyositis syndrome. J Small Anim Pract. 1987;28:891–908. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacques D, Cauzinille L, Bouvy B, et al. A retrospective study of 40 dogs with polyarthritis. Vet Surg. 2002;31:428–434. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2002.34665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorman NT, Werner LL. Immune-mediated diseases of the dog and cat: I. Basic concepts on the systemic immune-mediated diseases. Br Vet J. 1986;142:395–402. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(86)90040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrader SC. The use of the laboratory in the diagnosis of joint disorders of dogs and cats. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 1166–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chabanne L, Fournel C, Monier JC, et al. Canine systemic lupus erythematosus. Part 1. Clinical and biological aspects. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1999;21:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell SC, Hughes DE, Bennett D, et al. Analysis and significance of anti-nuclear antibodies in dogs. Res Vet Sci. 1997;62:83–84. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5288(97)90187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoren-Tolling K, Ryden L. Serum auto antibodies and clinical/pathological features in German shepherd dogs with lupus-like syndrome. Acta Vet Scand. 1991;32:15–26. doi: 10.1186/BF03546993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greig B, Armstrong PJ. Canine granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (A. phagocytophilum infection) In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greene CE, Straubinger RK. Borreliosis. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 417–435. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw SE, Day MJ, Lerga A, et al. Anaplasma (Ehrlichia) phagocytophila: A cause of meningoencephalitis/polyarthritis in dogs? J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:636. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavan M, Glickman N, Moore G, Caldanaro R, Lewis H, Glickman L. Prevalence of and risk factors for canine tick infestation in the United States, 2002–2004. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:65–75. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greig B, Asanovich KM, Armstrong PJ, Dumler JS. Geographic, clinical, serologic, and molecular evidence of granulocytic ehrlichiosis, a likely zoonotic disease, in Minnesota and Wisconsin dogs. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:44–48. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.44-48.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr AP, Michels G. Identifying noninfectious erosive arthritis in dogs and cats. Vet Med. 1997;92:804–810. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ralphs SC, Beale B. Canine idiopathic erosive polyarthritis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2000;22:671–677. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennet D. Immune-based erosive inflammatory joint disease of the dog: Canine rheumatoid arthritis. 1 Clinical, radiological, and laboratory investigations. J Small Animal Pract. 1987;28:779–797. [Google Scholar]