Abstract

A case of canine cutaneous sterile pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome (SPGS) with generalized asymmetrical alopecia and plaques is described. Results from histopathologic examination were suggestive of SPGS and failed to demonstrate any etiological agent. A systematic approach on how to definitively rule out infectious skin diseases is discussed.

Résumé

Syndrome du pyogranulome/granulome cutané stérile chez un chien. Cette étude décrit un cas de syndrome du pyogranulome/granulome cutané stérile (SPGS) chez un chien avec alopécie généralisée asymétrique et plaques. Les résultats de l’examen histopathologique étaient évocateurs d’un SPGS et n’ont pas démontré d’agent étiologique. Une approche systématique pour permettre d’exclure précisément les maladies infectieuses de la peau est discutée.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

A 6-year-old, intact male, 30 kg, American Staffordshire terrier was referred to the Section of Veterinary Internal Medicine of University of Naples “Federico II” (Italy) for evaluation of a case of nonpruritic alopecia with diffuse plaques. The lesions had started as papules and small nodules 2 mo prior to referral and had increased progressively in number and size over time. The dog lived mostly outdoors and had been administered a topical flea and tick preventative (Frontline spot-on; Merial, Assago, Milano, Italy) monthly. No systemic signs were reported. Dermatophytosis with secondary bacterial infection had been suspected by the referring veterinarian and antibiotic therapy [clavulanic acid — potentiated amoxicillin, 20 mg/kg body weight (BW), PO, q12h], along with antifungal therapy (griseofulvin, 25 mg/kg BW, PO, q12h), had been administrated for 40 d without any improvement in the skin condition.

Case description

On physical examination of the dog, mild bilateral prescapular and popliteal lymphadenopathy was observed. The dermatological examination revealed generalized, asymmetrical alopecia associated with circular plaques of varying diameter (1 to 5 cm) and nonfollicular papules affecting the head, neck, ventral aspect of the thorax and abdomen, and all 4 limbs (Figure 1). The plaques were covered by large scales, exhibited an erythematous border, and were not painful on palpation. These lesions did not blanch on diascopy. A complete blood (cell) count (CBC), a serum biochemical panel, and abdominal ultrasonography were performed. Results of CBC revealed a leucocytosis (22.0 × 109 cells/L, reference interval: 6 to 15.0 × 109 cells/L) with neutrophilia (19.1 × 109 cells/L, reference interval: 3.3 to 11.8 × 109 cells/L). Results from the serum biochemical panel were within reference intervals, except for an increase in total protein (89 g/L, reference interval: 60 to 80 g/L) with high serum β and γ globulin levels (total β globulin: 27 g/L, reference interval: 12 to 22 g/L; total γ globulin: 30 g/L, reference interval: 8 to 18 g/L).

Figure 1.

Photograph of the ventral aspect of the thorax and the medial aspect of the front limb: alopecia with erythematous papules and plaques.

The following differential diagnoses were considered: deep pyoderma (antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection); adult-onset generalized demodicosis; cutaneous histiocytosis; cutaneous lymphoma; atypical mycobacteriosis (canine leproid granuloma syndrome); sterile pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome; erythema multiforme; cutaneous vasculitis; and cutaneous leishmaniasis, because of the endemic spread of this protozoan in the area where the dog lived.

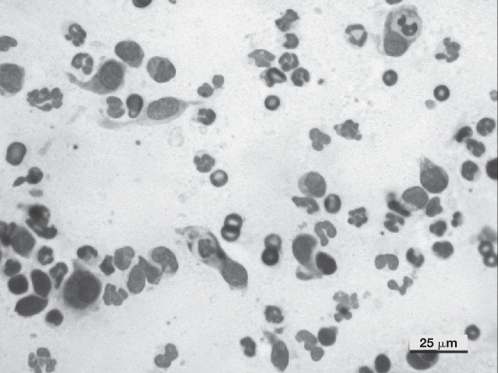

Multiple deep skin scrapings were negative for the presence of Demodex canis. Cytological examination by fine-needle aspirate of 1 plaque on the thorax revealed a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of macrophages and nondegenerate neutrophils (Figure 2). No microorganisms were seen.

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of a smear prepared from a fine-needle aspirate from 1 of the plaques: macrophages, nondegenerated neutrophils, and neutrophagocytosis. No microorganisms are present. (Diff-Quick; Bar = 25 μm).

Results from an indirect fluorescence antibody test (IFAT), based on cultured promastigotes of a Leishmania sp., and cytologic examination of the enlarged lymph nodes and bone marrow were both negative (IFAT < 1:40).

Multiple cutaneous excisional biopsies were obtained from plaques on the neck, limbs, and trunk, using local anesthesia (Lidocaine 2%, ATI, Bologna, Italy) and sedation with 0.6 mg, IV, of metedomidine (Domitor; Pfizer, Rome, Italy). The biopsies were fixed on cardboard in 10% buffered formalin for histopathological analysis. Sections were processed for histopathological evaluation, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E); also sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Ziehl–Neelsen, and Gram to rule out fungal and mycobacterial infection. In addition, sections were evaluated under polarized light to rule out the presence of foreign bodies. Finally, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique was used to test for the presence of Leishmania spp. and Mycobacterium spp. (1–3).

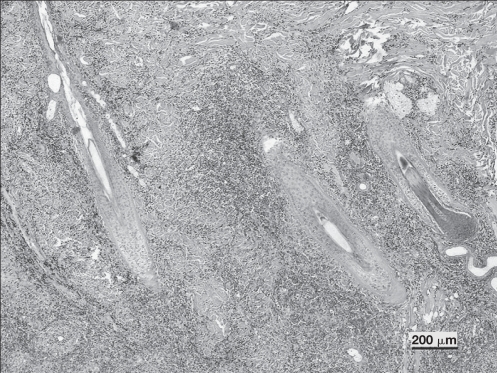

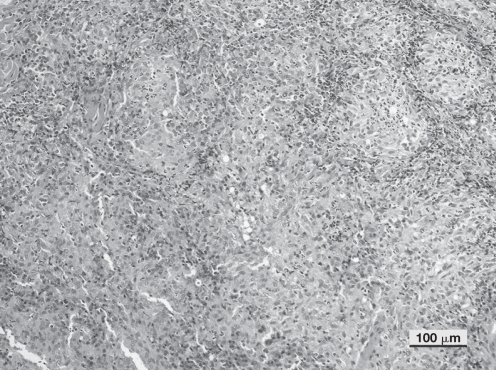

On histopathologic examination, the skin biopsy specimens showed a nodular to diffuse dermatitis, characterized by a vertically oriented cellular infiltrate in perifollicular areas (Figure 3). The predominant inflammatory cells were macrophages and neutrophils. The cellular infiltrate was diffusely oriented in the deep dermis and panniculus. Multiple aggregates of neutrophils with peripheral cuffs of macrophages, as well as clusters of plasma cells and lymphocytes, were observed (Figure 4). Some hair follicles and sebaceous glands were obscured by the pyogranulomatous infiltrate. Microorganisms were not observed, using the special stains employed. No foreign bodies were observed on polarized light examination.

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing nodular to diffuse dermatitis characterized by a vertical orientation of cellular infiltrate in perifollicular areas. Hair follicles are surrounded, but not invaded by the inflammatory cells. (Hematoxylin & eosin; Bar = 200 μm).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph showing higher magnification of Figure 3. The inflammatory infiltrate was characterized by a predominance of epithelioid macrophages with numerous neutrophils interspersed and rare lymphocytes and plasma cells. (Hematoxylin & eosin; Bar = 100 μm).

Finally, the PCR results ruled out the presence of Leishmania spp. or Mycobacterium spp. Based on the clinical and pathological findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous ‘sterile’ pyogranuloma/ granuloma syndrome (SPGS) was made.

Treatment with an immunosuppressive dose of prednisone (Deltacortene; Bruno Farmaceutici Spa, Rome, Italy), 2.5 mg/kg BW, PO, q24h, was started. In addition, antibiotic therapy, ciprofloxacin (Ciproxin; Bayer, Milan, Italy), 10 mg/kg BW, PO, q24h for 20 d, for protection against possible secondary infections was also administered. Because of the lack of clinical improvement in the skin lesions and the adverse drug effects (severe polyuria/polydypsia/polyphagia), the owner decided to discontinue treatment after only 15 d.

The dog was seen again 5 mo after the 1st referral visit, at which time all cutaneous lesions had completely resolved without any additional treatment. Moreover, the owner reported that the improvement had started 1 mo earlier (3.5 mo after discontinuation of the prednisone).

Discussion

In dogs, most granulomatous or pyogranulomatous skin lesions appear as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. The lesions may be solitary or multiple, and localized or generalized. They also can be alopecic or haired, and ulcerated, firm or fluctuant, and can vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters (4,5). The causes of granulomatous dermatitis in dogs and cats are various and numerous: the lesions can be associated with infectious agents, such as bacteria, algae, fungi, parasites, and protozoa, or noninfectious agents, like foreign bodies; idiopathic factors have also been reported (6,7). Microscopically, nodular and/or diffuse, granulomatous and pyogranulomatous dermatitis is commonly evident in dogs, but less so in cats (8). It is characterized by multifocal nodular inflammation of the dermis that tends towards confluence or a diffuse pattern (9). Cutaneous “sterile” pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome is an idiopathic, uncommon canine skin disorder. The pathogenesis is unknown, but the histiocytic nature of the inflammatory infiltrate, failure to demonstrate a causative agent, and the good to excellent response to glucocorticoids and other immunomodulating drugs support it being considered as an immune-mediated disorder (4). However, it has been hypothesized that SPGS may be related to an immune response against persistent endogenous or exogenous antigens, such as a Leishmania sp. and/or Mycobacterium sp., causing a granulomatous inflammatory reaction (9,10).

The clinical manifestations are characterized by firm, hair-covered to partially alopecic, erythematous papules, nodules, or plaques. The involved locations are more commonly the head (mainly bridge of nose, muzzle, and periocular region) and distal extremities, and less commonly the pinnae, eyes, trunk (lateral and dorsal aspect), and abdomen (4,5). In most cases, the lesions are multiple and without pain or pruritus. Possible lymphadenopathy has also been reported (5). Systemic signs associated with this syndrome have not been reported. The condition may resolve spontaneously or take a waxing and waning course (9). Histopathologically, SPGS is characterized by multifocal, nodular to diffuse, pyogranulomatous/granulomatous dermal infiltrates (4,6).

Diagnosis of SPGS is based on its clinical appearance, the histopathological findings, a failure to visualize microorganisms with the use of special stains (PAS, Ziehl-Neelsen, and Gram), a failure to demonstrate foreign bodies by polarized light microscopy, and negative results from microbiological examination of tissue cultures (8,9). In the present case, tissues were not cultured; so, to substitute for this diagnostic limitation, special stains were subsequently applied to histological sections in order to detect such microorganisms as cannot be seen with standard H&E staining (Leishmania spp. and Mycobacterium spp.).

The treatments most commonly used for SPGS are surgical excision of solitary nodules or plaques or systemic medications for multiple lesions, including immunosuppressive dosage of glucocorticoids and the use of tetracycline and niacinamide or azathioprine in cases where lesions are not responding to glucocorticoids (6,11). The use of antibiotics has also been reported to decrease the inflammation and drainage in the case of secondary bacterial infection (5). More specifically, the combination of tetracycline and niacinamide has been shown to have synergistic effects and numerous immunomodulatory properties, even though their mechanism of action in immune-mediated diseases is not totally understood. In fact, whereas tetracycline is able to inhibit in vitro production of antibodies, activation of complement, prostaglandin synthesis, and the function of lipases and collagenases, and iacinamide has the in vitro and in vivo ability to prevent mast cell degranulation, inhibit phosphodiesterases, and decrease protease release (6,12,13), their combination has demonstrated the ability to inhibit blast transformation of lymphocytes and the chemotaxis of neutrophils and eosinophils (11). The tetracycline/niacinamide combination is used at 250 mg of each in dogs less than 10 kg and 500 mg of each in dogs more than 10 kg, PO, q8h (6).

Sometimes, as in the present case, the lesions can have a waxing and waning course; total clinical resolution has also been reported (6,9). The pathogenic mechanism of waxing and waning or clinical resolution is not known. It is possible that the cessation of the abnormal immunological response against a possible chronic stimulus is the basis for this phenomenon.

Infection with a Leishmania sp. could mimic the clinical and histopathological findings of SPGS, and it is of particular importance to exclude leishmaniasis if it is endemic in the area. In canine leishmaniasis, nodules and/or plaques are reported in about 6% of the cutaneous lesions, as the result of histiocytic reaction against the protozoan, and can be observed on cytological and/or histological examination (14,15).

Similarly, the canine leproid granuloma syndrome can be characterized clinically and histopathologically by a granulomatous/pyogranulomatous dermatitis (6,9,16) and, in some cases, special stains, such as Ziehl–Neelsen, may provide negative results even in the presence of microorganism (16,17). In these cases, immunoshistochemical (IHC) staining, using polyclonal anti-Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) antibody or PCR, is necessary to definitely rule out a mycobacterial infection (2,17).

Because SPGS is diagnosed by a process of elimination and because of its similarities with other infectious and non-infectious (pyo) granulomatous diseases and the presence of a small number of parasites in the skin, its investigation should involve a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach. The use of the PCR technique should be considered to rule out, definitively, the presence of Leishmania or Mycobacterium in pyogranulomatous/ granulomatous skin lesions (1,2,18). In the present case, etiologic agents were not observed with the different techniques (cytologic examination, IFI, histopathologic examination, and PCR), which supported an idiopathic pathogenesis.

Plaque or nodular lesions in dogs are a diagnostic challenge for the veterinarian. This kind of lesion in adult to old dogs, with or without lymphadenopathy, should alert the clinician to neoplasia and/or immune-mediated disorders (histiocytosis, leishmaniasis, atypical mycobacterial granuloma, and sterile nodular dermatitis). The authors emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach in the diagnosis of “sterile” (nodular) diseases and the necessity of investigating the real “sterility” and the existence of SPGS in dogs. Multidisciplinary studies in larger populations are needed to investigate the etiology of this cutaneous disease.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Silvia Preziuso of the Department of Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Camerino (Italy), for the molecular diagnosis. CVJ

References

- 1.Roura X, Fondevila D, Sanchez A, et al. Detection of Leishmania infection in paraffin-embedded skin biopsies of dogs using polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1999;11:385–387. doi: 10.1177/104063879901100420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornegliani L, Fondevila D, Vercelli A, et al. PCR technique detection of Leishmania sp. but not Mycobacterium sp. in canine cutaneous ‘sterile’ pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome. Vet Dermatol. 2005;16:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2005.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranaz A, Lienana E, Pickering X, et al. Use of polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in cats and dogs. Vet Rec. 1996;138:276–280. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.12.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres SMF. Sterile nodular dermatitis in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1999;29:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(99)50129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panich R, Scott DW, Miller WH. Canine cutaneous sterile pyogranuloma/ granuloma syndrome: A retrospective analysis of 29 cases (1976 to 1988) J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1991;27:519–528. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott DW, Miller WJ, Griffin GE. Miscellaneous skin diseases. In: Muller, Kirk’s, editors. Small Animal Dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. pp. 1136–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fadok V. Granulomatous dermatitis in dogs and cats. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim) 1987;2:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yager JA, Wilcock BP. Color Atlas and Text of Surgical Pathology of the Dog and Cat. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby Year Book; 1994. pp. 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Non-infectious nodular and diffuse granulomatous and pyogranulomatous diseases of the dermis. In: Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK, editors. Skin Diseases of Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis. 2. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby Year Book; 2005. pp. 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeManuelle TC, Stannard AA. Difficult dermatologic diagnosis. Sterile nodular panniculitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213:356–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothstein E, Scott DW, Riis RC. Tetracycline and niacinamide for the treatment of sterile pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1997;33:540–543. doi: 10.5326/15473317-33-6-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peoples D, Fivenson DP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis: Successful treatment with tetracycline and nicotinamide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:498–499. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaffins ML, Collison D, Fivenson DP. Treatment of pemphigus and linear IgA dermatosis with nicotinamide and tetracycline: A review of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:998–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrer L, Rabanal RM, Domingo M, et al. Identification of Leishmania donovani amastigotes in canine tissues by immunoperoxidase staining. Res Vet Sci. 1988;44:194–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciaramella P, Oliva G, De Luna R, et al. A retrospective clinical study of canine leishmaniasis in 150 dogs naturally infected by Leishmania infantum. Vet Rec. 1997;141:539–543. doi: 10.1136/vr.141.21.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley JE, Borjesson D, Gross TL, et al. Clinical, microscopic, and molecular aspects of canine leproid granuloma in the United States. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:234–239. doi: 10.1354/vp.39-2-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik R. Mycobacterial diseases of cats and dogs. In: Hiller A, Foster AP, Kwochka KW, editors. Advances in Veterinary Dermatology. Vol. 5. Oxford: Blackwell publ; 2005. pp. 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Font A, Roura X, Fondevila D, et al. Canine mucosal leishmaniasis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1996;32:31–137. doi: 10.5326/15473317-32-2-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]