Abstract

The crystal structure of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia was determined at 2.8-Å resolution by the multiple isomorphous replacement method, using platinum and selenomethionine derivatives. The crystals belong to space group P43212, with unit cell parameters a = b = 105.9 Å and c = 161.9 Å. Dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV is a homodimer, and the subunit structure is composed of two domains, namely, N-terminal β-propeller and C-terminal catalytic domains. At the active site, a hydrophobic pocket to accommodate a proline residue of the substrate is conserved as well as those of mammalian enzymes. Stenotrophomonas dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV exhibited activity toward a substrate containing a 4-hydroxyproline residue at the second position from the N terminus. In the Stenotrophomonas enzyme, one of the residues composing the hydrophobic pocket at the active site is changed to Asn611 from the corresponding residue of Tyr631 in the porcine enzyme, which showed very low activity against the substrate containing 4-hydroxyproline. The N611Y mutant enzyme was generated by site-directed mutagenesis. The activity of this mutant enzyme toward a substrate containing 4-hydroxyproline decreased to 30.6% of that of the wild-type enzyme. Accordingly, it was considered that Asn611 would be one of the major factors involved in the recognition of substrates containing 4-hydroxyproline.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is a gram-negative bacterium that is well known as a nosocomial pathogen. This bacterium is a pathogen causing opportunistic infectious diseases, sapremia, endocarditis, and pneumonias (13). Most strains of S. maltophilia exhibit multiple resistances to a broad range of currently available antibiotics, and they represent a growing problem for public health. A type of drug whose actions are different from those of existing antibiotics and effective against S. maltophilia is therefore required.

Accordingly, we have noticed that S. maltophilia produces a proline-specific dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DPIV). DPIV (EC 3.4.14.5) is a serine peptidase belonging to peptidase family S9 and the prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) family. This enzyme is a homodimeric type II membrane-bound enzyme and hydrolyzes peptide substrates containing proline or alanine at the penultimate position to release an N-terminal dipeptide (23). DPIV has been isolated from bacteria as well as from various mammalian sources (3, 45, 57). In mammalian tissues, DPIV is known to function in the degradation of bioactive peptides, including growth hormone-releasing hormone (17), substance P (2, 43), and glucagon-like peptide I (29, 39). DPIV has also been identified as CD26 antigen, a surface differentiation marker involved in the transduction of mitogenic signals in thymocytes and T lymphocytes in mammals (7, 16, 55) and in cell matrix adhesion through specific interactions with fibronectin and collagen (4, 46). The crystal structures of human, porcine, and rat DPIV enzymes have been determined (14, 21, 35, 47). Although DPIV enzymes from bacteria and fungi, including Flavobacterium meningosepticum (56), Bacteroides fragilis (32), Prevotella intermedia (50), Porphyromonas gingivalis (11), Trichophyton rubrum (41), Lactobacillus helveticus (37), Aspergillus fumigatus (5), Aspergillus oryzae (52), etc., have been identified, no structural information has been reported regarding microbial DPIV. Some of these are known to be pathogenic bacteria, causing diseases such as athlete's foot (T. rubrum), periodontitis (P. intermedia and P. gingivalis), and a variety of opportunistic infectious diseases (F. meningosepticum, A. fumigatus, and B. fragilis). In bacteria, DPIV is principally involved in the degradation of peptides as a nutrient source. Among proteins that are potential substrates for bacterial DPIV, collagen is known for its high proline content. Type I collagen has a repeated sequence of (Gly-Xaa-Pro)n. Since Xaa-Pro and Pro-Xaa bonds are hardly hydrolyzed by ordinary proteases or peptidases, DPIV activity seems to be necessary to efficiently break down the peptides derived from collagen into amino acids as a nutrient. Considering that many pathogenic bacteria possess the DPIV gene, DPIV may play an important role, together with collagenase, in infection or growth of those pathogenic bacteria through the degradation of collagen.

We have reported the cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding Stenotrophomonas DPIV (25). Stenotrophomonas DPIV shows sequence identities of 24.0 and 23.6% with human and porcine DPIVs, respectively. Collagen contains 4-hydroxyproline (Hyp), which is produced by hydroxylation of some of the proline residues in collagen by proline 4-hydroxylase to stabilize the triple superhelix of collagen. In this study, we show that Stenotrophomonas DPIV exhibits activity toward a substrate containing 4-hydroxyproline, while only faint activity was detected for porcine DPIV. In order to clarify the structural determinants of Stenotrophomonas DPIV for this unique activity, we determined the structure of this enzyme.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the crystal structure of bacterial DPIV and its activity on a substrate containing 4-hydroxyproline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction endonucleases and various DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Bio Inc. and Toyobo Co., Ltd. Fast Garnet GBC, Z-Gly, and Z-Hyp were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Polyethylene glycol with a mean molecular weight of 6,000 was purchased from Hampton Research Inc. Tris-(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane and magnesium chloride were purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Japan. Porcine DPIV was purified from porcine kidney by a previously described method (58), and the enzyme solution was prepared to a concentration of 0.0697 mg/ml, as estimated on the basis of absorbance at 280 nm.

Synthesis of a substrate containing Hyp (Gly-Hyp-βNA).

Gly-Hyp-β-naphthylamide (Gly-Hyp-βNA) was synthesized by standard procedures in solution by condensation of benzyloxycarbonyl-glycine (Z-Gly) and Hyp-βNA with water-soluble carbodiimide, and the protected Z group was removed by hydrogenation over palladium carbon. Hyp-βNA was synthesized according to a previously reported procedure (42).

Data for Gly-Hyp-βNA are as follows: (α)D23, 34.6° (c 0.24, MeOH); 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ, 2.16 (1H, ddd, J = 12.9, 8.4, and 4.5 Hz), 2.30 to 2.36 (1H, m), 3.47 to 3.52 (3H, m), 3.74 (1H, dd, J = 10.6 and 4.2 Hz), 4.56 (1H, brs), 4.70 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.36 to 7.46 (2H, m), 7.58 (1H, dd, J = 8.6 and 2.3 Hz), 7.74 to 7.82 (3H, m), and 8.19 (1H, s); IR (undiluted), 3,448, 1,635, 1,560, 1,506, 1,434, 1,230, 1,081, and 817 cm−1; HRMS(FAB) calculated for C17H19N3O3, 313.1426 (M+); found value, 313.1432.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Escherichia coli DH5α (supE44 ΔlacU169 φ80dlacZΔM15 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1) and XL1-Blue (endA1 gyrA96 hsdR17 lac recA1 relA1 supE44 thi-1 F′ [proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10]) were used as hosts for expression of wild-type and mutant enzymes, respectively. The 3.2-kb fragment containing the 2,226-bp open reading frame was cloned into the BamHI site of the pUC19 plasmid to produce pUC19-SDP4 (25). Transformants were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani medium (LB medium). Nutrient broth (N broth) was used for enzyme production. A BamHI fragment of the DPIV gene was subcloned into pET11d plasmid to produce pET11d-SDP4 vector. For expression of a selenomethionine (SeMet) derivative, E. coli B834 strains transformed by the pET11d-SDP4 vector were grown in LeMaster medium.

Construction of N611Y mutant enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis.

A site-directed mutation was introduced into the gene by the PCR-based megaprimer mutagenesis strategy (54). pUC19-SDP4 was digested with BamHI, and the 3.2-kb fragment containing the gene for Stenotrophomonas DPIV was used as the template to produce the N611Y mutant. The first round of PCR was carried out using the oligonucleotides 5′-GTAACCGCCGTAGGACCAGCC-3′ and 5′-CAACCAGTACCTGGCCCAGC-3′ as the mutagenic and flanking primers, respectively. The megaprimer of 211 bp was amplified in the first round. A PCR product of 425 bp was then amplified by a second round of PCR using the megaprimer and the flanking primer 5′-CGTCAGCCATGCCGTGGATC-3′. The DNA fragment of 238 bp containing the mutation was prepared by digesting the PCR product with BstXI and MluI, and the resultant fragment was inserted into the same restriction sites of the pUC19-SDP4 vector to produce pUC19-SDP4-N611Y. The mutations were confirmed by sequence analysis.

Overexpression and purification of Stenotrophomonas DPIV.

E. coli DH5α transformed with pUC19-SDP4 was aerobically cultured in 20 liters of N broth containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 15 h, using a jar fermenter (MBS, Japan). The cells were suspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and were disrupted by repeated sonication on an ice bath. After centrifugation at 22,540 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was fractionated with ammonium sulfate from 35 to 80% saturation. The precipitate was dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 35% saturated ammonium sulfate. The enzyme solution was applied to a Toyopearl HW65C column and eluted with a decreasing linear gradient from 35 to 0% saturated ammonium sulfate. The active fractions were combined and precipitated by ammonium sulfate at 80% saturation. The precipitate was dissolved and dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The resultant solution was applied to a DEAE-Toyopearl 650C column and eluted with the same buffer. The fractions passing through the column were collected, leaving a large fraction of the unwanted proteins on the column. After concentration by ultrafiltration (PM-10; Amicon), the enzyme solution was dialyzed against 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). Finally, the enzyme was purified by hydroxyapatite column chromatography, using a linear gradient of 10 to 400 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). Active fractions were combined and concentrated using Centriprep and Centricon microconcentrators (YM-30; Millipore). The enzyme solution was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The N611Y mutant enzyme was overexpressed in E. coli XL1-Blue cells transformed by pUC19-SDP4-N611Y and purified by essentially the same methods as those used for the wild-type enzyme. The SeMet derivative enzyme was produced by an overexpression system using strain B834 transformed by pET11d-SDP. The mutant and SeMet derivative enzymes were purified using the same method as that for the wild-type enzyme.

Enzyme activity assay.

The activity of Stenotrophomonas DPIV was assayed using Gly-Pro-βNA as the substrate. The reaction mixture consisted of 0.8 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 0.1 ml of enzyme solution, and 0.1 ml of 3 mM Gly-Pro-βNA. After incubation at 37°C for 10 min (unless specifically indicated otherwise), the reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 ml of Fast Garnet GBC (1 mg/ml) solution containing 10% Triton X-100 in 1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0). The absorbance at 550 nm was measured after 20 min. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 μmol of substrate per min under the above conditions.

To determine the Km values for Gly-Pro-βNA and Gly-Hyp-βNA, the substrate concentrations were varied. For activity measurements with Gly-Pro-βNA, solutions of porcine, Stenotrophomonas, and N611Y mutant enzymes were prepared at almost the same concentration. Lineweaver-Burk plots were used to calculate Km and Vmax. The enzyme concentrations of Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs were estimated from E1%, 280 nm values of 1.45 and 2.15, respectively. For the kcat calculations, 82,100 and 88,200 were used as the molecular weights of the Stenotrophomonas and porcine enzymes, respectively.

Crystallizations and X-ray data collection.

The protein solution (10 mg/ml) was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution, and a droplet was equilibrated against reservoir solution (10% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol 6000, 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], and 0.2 M MgCl2). After 2 days, a small crystal was transferred into a preequilibrated droplet. Prism-shaped crystals appeared within a week of incubation after the seeding and grew to maximum dimensions of 0.4 by 0.4 by 0.3 mm. The X-ray diffraction data were collected to 2.8-Å resolution with a Rigaku R-Axis IV detector, using CuKα radiation focusing by an osmic confocal mirror. Since the crystals were sensitive to measurement under nitrogen gas at 100 K, data collection was performed at 293 K, using crystals enclosed within glass capillaries with a small amount of mother liquor. From the data, the crystal was determined to belong to space group P41212 or P43212, with the following crystal dimensions: a = b = 105.9 Å and c = 161.9 Å. Assuming that one subunit of the dimer is an asymmetric unit, the Matthews coefficient VM was calculated to be 2.39 Å3 Da−1, indicating a solvent content of approximately 48.5% in the unit cell (36). These values are within the ranges typical for protein crystals (28). Crystals of the SeMet derivative were obtained using the same method as that for the wild-type crystal, and those of a Pt derivative were obtained by soaking crystals in a crystallization solution containing 6.6 mM platinum(II) potassium chloride for 14 h. The diffraction data for SeMet and Pt derivative crystals were collected to 2.9- and 3.0-Å resolution, respectively, using an R-Axis IV detector at 293 K. All data were processed and scaled by MOSFLM (34) and SCALA from the CCP4 suite (10).

Crystal structure determination and structure refinement.

The structure of DPIV was determined by the multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) method, using the platinum derivative and the SeMet derivative. The scaling of all data and the map calculations were performed with the CCP4 program suite (10). Determination of heavy atom binding sites was performed with the program SOLVE (53). Through determination of heavy atom sites, the space group was determined to be P43212. Refinement of the heavy atom parameters, calculations of the initial phases, and electron density improvement by the process of solvent flatting were performed with the program SHARP (12). The model was gradually built into a Fourier map at 3.0-Å resolution, using the program XtalView (38).

The structure was refined by simulated annealing and energy minimization with the program CNS (8). The structure was scrutinized by inspection of the composite omit map. Refinement and model rebuilding were alternately carried out for several cycles, and water molecules were then picked up on the basis of the peak height and the distance criteria from the difference map. Water molecules whose thermal factors were above 60 Å after refinement were removed from the list. After several rounds of refinement by energy minimization and manual rebuilding, the final residual factors were the Rfactor value of 18.5% and the Rfree value of 23.9%, using 23,264 reflections from 20- to 2.8-Å resolution (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Data collection, MIR, and refinement statisticsa

| Parameter | Value for enzyme

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | K2PtCl4 derivative | SeMet derivative | |

| Data collection parameters | |||

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 | P43212 |

| Cell constants | |||

| a, b (Å) | 105.9 | 105.8 | 105.8 |

| c (Å) | 161.9 | 162.3 | 162.2 |

| Temperature (K) | 293 | 293 | 293 |

| Radiation source | CuKα | CuKα | CuKα |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.0-2.80 (2.95-2.80) | 40.0-3.00 (3.16-3.00) | 40.0-2.90 (3.06-2.90) |

| No. of reflections | |||

| Observation | 180,873 | 37,218 | 86,800 |

| Unique | 23,396 (3,326) | 15,201 (2,291) | 21,128 (3,015) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 80.6 (80.6) | 100 (100) |

| Rsym | 0.077 (0.333) | 0.086 (0.295) | 0.082 (0.305) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 8.3 (2.2) | 6.5 (2.2) | 7.9 (2.3) |

| MIR parameters | |||

| Riso | 0.127 | 0.111 | |

| Phasing power | 1.09 | 1.34 | |

| No. of derivative sites | 3 | 10 | |

| Refinement parameters | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.0-2.80 | ||

| R factor | 0.185 | ||

| Rfree | 0.239 | ||

| Wilson B factor | 56.8 | ||

| Average B factors | |||

| Total protein atoms (Å2) | 41.0 | ||

| Main chain atoms (Å2) | 40.5 | ||

| Side chain atoms (Å2) | 41.6 | ||

| Water molecules (Å2) | 30.9 | ||

| RMS square deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | ||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.31 | ||

Riso = Σ||FPH| − |FP||Σ|FP|, where |FPH| and |FP| are the derivative and native structure factor amplitudes, respectively. Phasing power is the ratio of the RMS of the heavy atom scattering amplitude and the lack of closure error. Values in parentheses refer to the last resolution shell.

Protein structure accession number.

The atomic coordinates and structural factors for Stenotrophomonas DPIV (PDB code 2ECF) have been deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (http://www.wwpdb.org) and the Protein Data Bank Japan at the Institute for Protein Research at Osaka University (http://www.pdbj.org/).

RESULTS

Expression and purification of enzymes.

Recombinant DPIV was purified by sequential column chromatography. The wild-type enzyme was purified 302-fold, with a recovery rate of 16.9%. The purified enzyme was homogeneous by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The enzyme solution was concentrated to 33.2 mg/ml, as estimated from measurement of the absorbance at 280 nm. The N611Y mutant enzyme was purified using the same method as that for the wild-type enzyme.

Activity toward a substrate containing Hyp.

The activity of Stenotrophomonas DPIV was compared with that of the porcine enzyme, using Gly-Pro-βNA and Gly-Hyp-βNA as substrates (Table 2). Although the activity of Stenotrophomonas DPIV toward Gly-Hyp-βNA was lower than that toward Gly-Pro-βNA, the enzyme was able to cleave the substrate containing the Hyp residue. The estimated kcat/Km value for Gly-Hyp-βNA was 2.2% of that for Gly-Pro-βNA. The N611Y mutation resulted in a reduction of activity toward Gly-Hyp-βNA; the estimated kcat/Km value decreased to 0.94% of that toward Gly-Pro-βNA. However, the kinetic parameters of porcine DPIV toward Gly-Hyp-βNA were unable to be estimated because of its extremely low activity.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of porcine and Stenotrophomonas DPIVs

| Substrate | Porcine DPIV

|

Stenotrophomonas DPIV

|

N611Y mutant DPIV

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | |

| Gly-Pro-βNA | 0.27 | 211 | 781 | 0.10 | 131 | 1,310 | 0.16 | 154 | 962 |

| Gly-Hyp-βNA | Not detected | 0.47 | 13.8 | 29.4 | 0.92 | 8.3 | 9.0 | ||

In order to confirm the significance of the activity toward Gly-Hyp-βNA, we carried out activity assays at various pH and salt concentrations. The activity varied significantly, and the maximum values were obtained at pH 8.0 and in the presence of 50 mM KCl. However, the activity ratios (Gly-Pro-βNA versus Gly-Hyp-βNA) for wild-type DPIV and the N611Y mutant were almost the same under the conditions tested, and 2 to 5% of the activity toward Gly-Pro-βNA was always observed with Gly-Hyp-βNA. It is suggested that the activity toward Gly-Hyp-βNA is not an unconventional activity exhibited under some special conditions but rather an intrinsic one associated with Stenotrophomonas DPIV.

Structure quality.

The refined model of the wild-type enzyme consists of 700 residues and 66 water molecules, with an Rfactor value of 18.5% at 2.8-Å resolution. This model lacks the 21 N-terminal residues (Met1 to Glu21) and an additional 20 residues (Pro87 to Ala106) due to the lack of unequivocal electron density. Alanine models were applied in the cases of Arg61, Lys137, Gln138, Glu139, Lys141, Lys368, and Lys370 because the electron density map corresponding to the side chains of these residues was weak or not observed at all. The average thermal factor was 41.0 Å2, and those of the main chain atoms, side chain atoms, and waters were 40.5, 41.6, and 30.9 Å2, respectively. The average thermal factor of the main chain atoms was higher than that of water molecules. It is likely that some magnesium ions were included in residual peaks assigned as water molecules. However, we could not assign any magnesium ions from the peak height and interactions with the neighboring residues. PROCHECK (33) analysis of stereochemistry revealed that all of the main chain atoms, with the exception of Ser610, fell within the generously allowed region of the Ramachandran plot, with 501 residues (84.2%) in the most favored region, 89 residues (15.0%) in the additionally allowed region, and 4 residues (0.7%) in the generously allowed region. On the basis of the electron density map, the conformation of the Ser610 residue was validated.

Overall structure and subunit assembly.

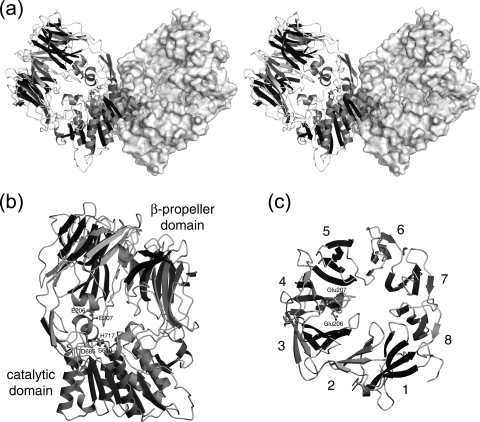

The dimer and subunit structures are shown in Fig. 1. Two subunits are mutually related by the crystallographic twofold rotation axis. The subunit interface is predominantly occupied by hydrophobic interaction of the catalytic domain and two extended antiparallel strands protruding from the β-propeller blade 4.

FIG. 1.

Crystal structure of Stenotrophomonas DPIV. (a) The dimer structure of Stenotrophomonas DPIV is shown by a stereo diagram. One of the two subunits is shown as a ribbon model, and the other is shown as a surface diagram. The diagram was drawn with the programs MOLSCRIPT (31) and Raster3D (40) and rendered with the program PYMOL (http://www.pymol.org/). (b) The subunit structure is shown as a ribbon model. The subunit was composed of two domains, the N-terminal β-propeller domain (top) and the C-terminal catalytic domain (bottom). The catalytic triad and two glutamate residues at the active site are shown as ball-and-stick models. (c) Ribbon model of the β-propeller domain, looking down upon the model as shown in diagram b, with assigned blade numbers. The last two diagrams were drawn with the program POVSCRIPT+ (15) and rendered with the program POVRAY (http://www.povray.org/).

The subunit in an asymmetric unit is composed of two domains, the N-terminal β-propeller and the C-terminal catalytic domains. The catalytic triad, Ser610, Asp685, and His717, belonging to the catalytic domain is located at the interface of two domains. The C-terminal catalytic domain possesses an α/β-hydrolase fold with a central eight-strand β-sheet sandwiched by nine α-helices.

Although the Fourier map for a part of propeller blade 1 was obscure, the N-terminal β-propeller domain was found to consist of eight blades. Each blade was composed of four antiparallel strands, with the exception of propeller blade 4. Propeller blade 4 was composed of β4A, β4A′, β4B, β4E, and β4F strands. In addition, propeller blade 4 included an α2 helix between β4A and β4A′ and two antiparallel β-strands (β4C and β4D) involved in the formation of a homodimer. Glu206 and Glu207 residues were found on the α2 helix. These glutamate residues function in the recognition of the N-terminal amino group of a substrate (14, 21, 35, 47). The β-propeller domain forms a funnel shape with a solvent-filled tunnel at the center of eight blades. The domain interface between the β-propeller and the catalytic domains was sustained by the fourth to eighth blades, and no interactions existed between the region of the first to third blades of the propeller and the catalytic domain. Consequently, a gaping hole was formed on the side face of the protein, and the active site was exposed to the solvent.

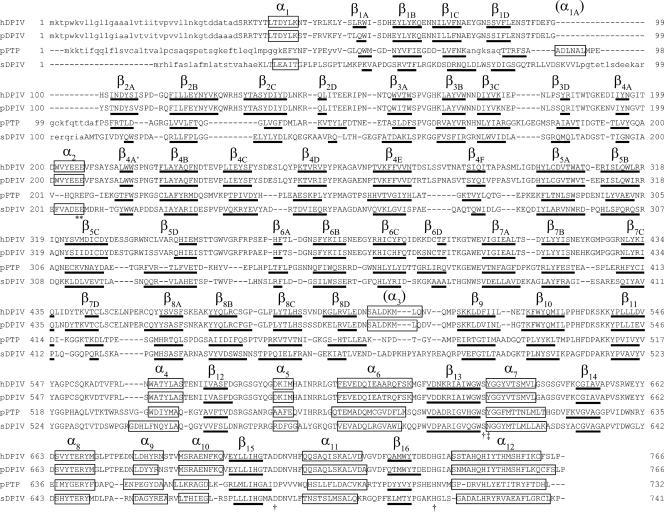

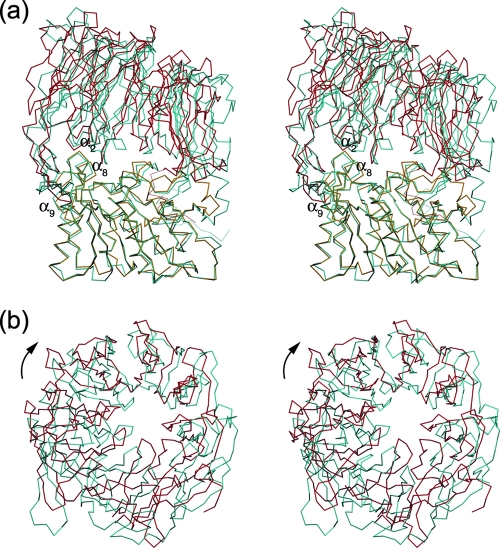

As shown in Fig. 2, the results of the structure-based sequence alignment clearly showed a similarity of primary and secondary structures between Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs. Secondary structures were assigned using DSSP (27). To clarify the structural differences between Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs, the subunit structure of porcine DPIV (PDB code 1orw) was superimposed onto that of the Stenotrophomonas enzyme by least-squares fitting of corresponding C-α positions. Two enzymes were fit within a root mean square (RMS) deviation of 2.59 Å, with a maximum displacement of 13.2 Å. As shown in Fig. 3, the structure of the Stenotrophomonas catalytic domain is very similar to that in porcine DPIV: the RMS deviation between the domains of the two enzymes is 0.83 Å, with a maximum displacement of 6.42 Å. In contrast, the RMS deviation of C-α positions between structurally corresponding residues in the β-propeller domains of the two enzymes is 2.25 Å, with a maximum displacement of 13.2 Å. Consequently, the structure of the Stenotrophomonas β-propeller domain is somewhat different from that in the porcine enzyme. In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, the β2B and β2C strands of β-propeller blade 2 are shorter than those in the porcine enzyme. Therefore, the side face of the β-propeller domain opens wider than that of porcine DPIV. In porcine DPIV, an additional difference can be found in the loop between the β2B and β2C strands. Arg125, located within the loop, is one of the significant residues composing the active site and interacts with the glutamate residue, which recognizes an N-terminal amino group of the substrate (14). In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, however, the position of this loop is too far away for the residues on this loop to interact with any residues at the active site. Furthermore, the relative position of the β-propeller domain is significantly shifted from that in the porcine enzyme. When the β-propeller domain was viewed from the top of the domain, this domain was rotated approximately 10° clockwise from the position of that in the superimposed porcine enzyme around the loop connecting two domains as a rotation axis.

FIG. 2.

Structure-based sequence alignment and associated secondary structures of human, porcine, and Stenotrophomonas DPIVs. The primary structures are aligned on the basis of a three-dimensional structure, using DaLiLite (44). hDPIV, pDPIV, and sDPIV indicate human, porcine, and Stenotrophomonas DPIVs, respectively. Capital and lowercase letters show the parts where the structure is known and unknown, respectively. The secondary structural elements are indicated by boxes labeled α for α-helices and by bold lines labeled β for β-strands. The catalytic triad and residues comprising the hydrophobic pocket are indicated by daggers and double daggers, respectively. Asterisks indicate two glutamate residues recognizing the substrate N-terminal amino group.

FIG. 3.

Stereo diagram of the superimposed structure of porcine DPIV on that of Stenotrophomonas DPIV. The red and orange lines represent the β-propeller and catalytic domains of Stenotrophomonas DPIV, respectively, and the cyan line represents porcine DPIV (PDB code 1orw). C-α trace diagrams of the subunits (a) and the β-propeller domains (b) are shown. Diagram b is a view from the zenith direction of diagram a. The arrow indicates the rotational direction of the β-propeller domain around the loops between two domains as the hinge. The diagrams were drawn using the programs MOLSCRIPT (31) and Raster3D (40).

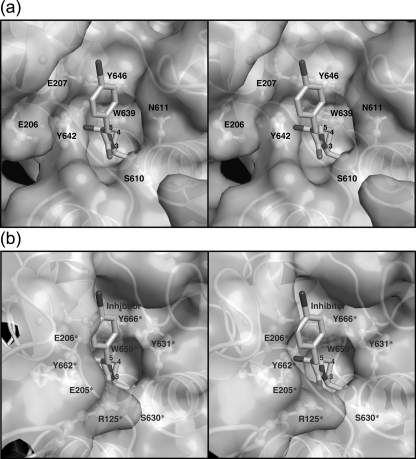

Active site of Stenotrophomonas DPIV.

The active-site structure of DPIV is shown in Fig. 4. The position of the catalytic triad, Ser610, Asp685, and His717, was found to be conserved in enzymes belonging to the POP family (14, 18, 21, 35, 47), and the active-site serine was also found to have the disallowed conformation in the Ramachandran plot. The Tyr524 residue corresponds to Tyr547 in porcine and human DPIVs, and this residue functions as an oxyanion hole (6). The catalytic domain of DPIV possesses a hydrophobic pocket to accommodate the proline residue at the second position from the N terminus in the substrates. In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, the hydrophobic pocket is composed of the Asn611, Val636, Trp639, Tyr642, Tyr646, and Val688 residues. The corresponding residues of porcine DPIV are Tyr631*, Val656*, Trp659*, Tyr662*, Tyr666*, and Val711*, respectively (residues marked with asterisks indicate residues from porcine DPIV). These residues are well conserved between the two DPIVs, except for Asn611. Two glutamate residues, Glu206 and Glu207, are located on the short α2 helix protruding from the inner surface of the β-propeller domain. Due to the displacement of the β-propeller domain, the distance from Glu206 or Glu207 to the catalytic serine residue, Ser610, was 1.9 or 1.3 Å longer than that between the corresponding residues, Glu205* or Glu206* and Ser630*, in the porcine enzyme. The side chain of Glu207 interacted with the Asp643 residue, with a distance of 2.9 Å. This is in good agreement with previously reported DPIV structures (14, 21, 34, 46).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the active site of Stenotrophomonas DPIV with that of porcine DPIV. The active sites of Stenotrophomonas DPIV (a) and porcine DPIV complexed with an inhibitor (PDB code 1orw) (b) are shown by ribbon-and-stick models. (c) Stereo view of the ribbon-and-stick models, superimposing the active site of Stenotrophomonas DPIV onto that of porcine DPIV. The diagrams were drawn using the programs POVSCRIPT+ (15) and POVRAY (http://www.povray.org/).

From the superposition of the structures of Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs, the positions of the catalytic triad and of Asn611, Tyr614, Val636, and Val688 of the hydrophobic pocket virtually overlapped with the corresponding residues from the porcine enzyme. A significant difference was observed, however, for the C-α atoms of Glu206 and Glu207, which were located 3.0 and 2.5 Å away, respectively, from the locations of the Glu205* and Glu206* residues. Additionally, Trp639, Tyr642, Asp643, and Tyr644, belonging to the α8 helix in the catalytic domain, were found to be 1.1, 1.4, 1.7, and 1.3 Å away, respectively, from the corresponding residues in superimposed porcine DPIV. In the catalytic domain, the structure of Thr637 to Arg674, including the α8, α9, and α10 helices, particularly exhibited a large difference from the corresponding region in porcine DPIV. Although the position of Trp639 was close to the expected position from the substrate for Trp659*, other residues were shifted far from the positions for the corresponding residues. Consequently, the conformational change of this region led to size expansion of the hydrophobic pocket compared to that of porcine DPIV.

DISCUSSION

Stenotrophomonas DPIV shows relatively high amino acid sequence identity with human and porcine DPIVs. In particular, the primary structures of the catalytic domain among the three DPIVs are well conserved. On the other hand, sequence identity among β-propeller domains is low: the β-propeller and catalytic domains of Stenotrophomonas DPIV show identities of 12.0 and 29.0% with human DPIV and 10.7 and 30.1% with porcine DPIV, respectively. The folding pattern of Stenotrophomonas DPIV corresponds with that of human and porcine DPIVs, as shown in Fig. 3. Structure comparison using the DaLiLite program (22) exhibited Z scores of 38.4 and 38.5 with human and porcine DPIVs, respectively. However, a superimposition of the structures of Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs revealed a significant difference between them, especially in the β-propeller domain. RMS deviations of C-α atoms of the corresponding residues belonging to the β-propeller and catalytic domains were 2.25 and 0.83 Å, respectively. Although the structures of both catalytic domains were nearly identical to each other except for the α8 and α9 helices, it was evident that the structure of the β-propeller domain in Stenotrophomonas DPIV largely differed from that in porcine DPIV.

Stenotrophomonas DPIV exhibited activity toward Gly-Hyp-βNA, with a kcat/Km value of 29.4. Porcine DPIV also exhibited faint activity toward this substrate. However, we could not estimate its kinetic parameters from the measurement, even for a twofold higher enzyme concentration than that of Stenotrophomonas DPIV.

DPIV releases the dipeptide Xaa-Pro from a substrate. During Michaelis complex formation, the Pro at the penultimate position of the substrate is recognized by the hydrophobic pocket on the catalytic domain, and the N-terminal amino group is recognized by two glutamate residues from the β-propeller domain. The superposition of the active site between Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs is shown in Fig. 4c. The catalytic triad includes the Ser610, Asp685, and His717 residues, and the corresponding residues are Ser630*, Asp708*, and His740* in the porcine enzyme. These residues are located at almost the same positions. Residues comprising the hydrophobic pocket in Stenotrophomonas DPIV are well conserved in porcine DPIV, expect for Ans611. In porcine DPIV, Tyr631* is found at the same position as Asn611 in Stenotrophomonas DPIV. Both Tyr631* and Asn611 face the fourth position of the pyrrolidine ring when the Pro of a substrate is bound to the hydrophobic pocket. Protein surface diagrams for the active sites of Stenotrophomonas and porcine DPIVs are shown in Fig. 5. In porcine DPIV, the size of the hydrophobic pocket is suitable to accommodate the Pro residue of a substrate. There is, however, no space to accommodate the 4-hydroxy group of the Hyp residue of a substrate, indicating that it is unlikely that a substrate containing a Hyp residue can bind to the active site due to the steric hindrance between the hydrophilic 4-hydroxy group of the Hyp residue and the hydrophobic side chain of the Tyr631* residue in porcine DPIV. In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, a small cavity was found at the same position. Since the Trp639 residue located adjacent to Asn611 and the C-β atom of Asn611 cause some steric hindrance for a 4-hydroxy group to bind to the enzyme, the cavity size may not be sufficient to accommodate the entire 4-hydroxyl group of the Hyp residue. This is likely to be the major reason for the relatively poor activity toward the Gly-Hyp substrate. It is expected that the Hyp residue could be bound to the active site through a hydrogen bond between the 4-hydroxyl group of the Hyp residue and the carbonyl oxygen of the Asn611. This Asn611 is conserved in DPIVs from Xanthomonas campestris (NCBI GenInfo identifier gi:21233383), Xanthomonas axonopodis (gi:21244763), Xanthomonas oryzae (gi:58580021), and Myxococcus xanthus (gi:108759702); their sequence identities with Stenotrophomonas DPIV are 78.7, 76.6, 76.6, and 23.9%, respectively. In most of the DPIV sequences deposited in databases, however, a tyrosine or phenylalanine residue is conserved as the corresponding residue, and its importance for DPIV activity has been reported (44). With a substitution of Tyr for the Asn611, the activity of the N611Y mutant toward Gly-Hyp-βNA decreased to 30.6% of that of the wild-type enzyme with regard to the kcat/Km value. Prolyl aminopeptidase (PAP) from Serratia marcescens is a proline-specific serine peptidase that possesses a hydrophobic pocket to accommodate the N-terminal Pro of a substrate at the active site. Furthermore, it has been reported that PAP exhibits activity toward substrates containing Hyp or 4-acetoxy-Pro as the N-terminal residue, and this activity comes from the extra space on the segment of the hydrophobic pocket that can accommodate a functional group at the fourth position of the pyrrolidine ring of a substrate (36). In a similar manner to the extra space in PAP, the difference in residue composition in the hydrophobic pocket seems to be one of the major factors in activity toward the Hyp-containing substrate.

FIG. 5.

Surface diagrams of the active site. (a) The protein surface of the active site of Stenotrophomonas DPIV is represented with ribbon and ball-and-stick models. The position of an inhibitor, shown as a stick model, was simulated on the basis of the fitted model of porcine DPIV, using the least-squares method. (b) The protein surface of porcine DPIV (PDB code 1orw) is represented with ribbon and ball-and-stick models. Numbers on the pyrrolidine ring of the inhibitor are location numbers.

It is well known that many peptidases are not capable of efficiently hydrolyzing peptide bonds around a proline residue. There are, however, some enzymes that can hydrolyze proline-containing peptides, although their activities are low. For example, the widely distributed aminopeptidase N shows a very broad specificity, with high activities toward arginine and alanine. We have determined the crystal structure of E. coli aminopeptidase N (24). The activity toward N-terminal proline was very low, as the kcat/Km value for Pro-βNA was only 0.4% of that for Ala-βNA, but it was present. The enzyme that releases N-terminal proline residues from peptides is PAP. This enzyme was first reported by Sarid et al. for Escherichia coli (48), and the activity was thereafter detected in other microorganisms. Two kinds of genes have been cloned from several bacteria, including Bacillus coagulans and Serratia marcescens (26, 30). However, no homologous sequences were found in the E. coli genome. We tried to clone the gene encoding PAP, and the clone that expressed a protein having PAP activity turned out to be a gene for aminopeptidase N (unpublished result). Aminopeptidase N is considered to be a major aminopeptidase in E. coli (9). Even a faint activity could be a significant factor in the degradation of particular peptides, such as collagen-derived peptides, if no other specific enzymes are available in given cells. At present, no data are available on whether a reduced growth phenotype is observed for DPIV-deficient bacteria in the presence of collagen as a major nutrient source. Nevertheless, the low but significant activity on Hyp-containing peptides should produce more amino acids as a nutrient and may help in the breakdown of collagen for bacterial infection.

DPIV belongs to the POP family. The structures of POPs from the pig, Novosphingobium capsulatum, and Myxococcus xanthus have been reported (18, 49) (PDB codes 1QFM, 1YR2, and 2BKL, respectively). Among POP sequences from vertebrates, insects, plants, fungi, bacteria, and archaea available in the sequence database, an asparagine corresponding to Asn611 in S. maltophilia DPIV is well conserved as the subsequent residue of the catalytic Ser610 residue. This suggests that POP might have some activity toward substrates containing a Hyp residue. In the structure of POP, however, no apparent cavity that could accommodate a 4-hydroxyl group of proline was found (18, 19, 20, 49, 51), and activity toward Hyp-containing peptides has not been reported. In porcine POP, the amide group of Asn555 is buried in the protein because Phe476, which is a component of the hydrophobic pocket, is located on the upper space of Asn555 and covers it. In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, the Tyr646 is located in place of Phe476 at a similar position on the hydrophobic pocket, but with a different conformation. The arrangement of residues constituting the hydrophobic pocket in DPIV differs from that in POP, since the different conformation of Tyr646 occurring in the upper side of Trp639 does not interfere with the Asn611 to be exposed to the solvent. The particular arrangement of the hydrophobic pocket in Stenotrophomonas DPIV seems important for reactivity toward Hyp-containing substrates.

Two glutamates in the α2 helix from the β-propeller domain are important residues that define the aminopeptidase activity of DPIV. These residues are essential for the enzyme activity, as they recognize the N-terminal amino groups of the substrates (1). In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, Glu206 and Glu207 correspond to Glu205* and Glu206*, respectively, in porcine DPIV. The distances of Glu206 and Glu207 from Ser610 are 15.8 and 15.9 Å, respectively. In contrast, the distances between the corresponding residues in porcine DPIV are 13.9 and 14.6 Å, respectively. The positions of Glu206 and Glu207 are too far away to interact with the N-terminal amino group of the substrate because the distances between the side chains of Glu206 and Glu207 and the expected N-terminal position of a substrate are estimated to be 5.40 and 3.87 Å, respectively. It was considered that this conformation in Stenotrophomonas DPIV is generated by a change in the relative position of the β-propeller domain, by a rotation of approximately 10° from the position in porcine DPIV. Glu206 and Glu207 would need to approach the N terminus of a substrate when the substrate is bound to the active site. Therefore, it is considered that a conformational change of the subunit is essential to produce the peptidase activity of Stenotrophomonas DPIV through displacement of the β-propeller domain to the same position as that in porcine DPIV.

If the β-propeller domain in porcine DPIV was rotated to the position in Stenotrophomonas DPIV, the β4C and β4D strands would move away from the catalytic domain and the β-propeller blades 4 and 5 would conflict with helices α8 and α5, respectively. On the other hand, in the model, where the β-propeller domain of Stenotrophomonas DPIV was rotated as a rigid body, a portion of the β4C and β4D strands conflicted with the Gly682 to Ala684 and Pro713-Gly714 residues belonging to the catalytic domain. If the β-propeller domain was rotated on loops connecting two domains, with the β4C and β4D strands migrating along the surface of the catalytic domain to the positions in porcine DPIV, two glutamates would be located in suitable positions for recognizing an N-terminal amino group of the substrate. In Stenotrophomonas DPIV, residues Thr637 to Arg674, comprising helices α8, α9, and α10, differ from the structure of the corresponding region in porcine DPIV and are located on the domain interface (Fig. 3A). In the rotated model, the α8 helix conflicted with β-propeller blades 4 and 5. With the conformational change caused by the displacement of the β-propeller domain, it was considered that this region, especially the α8 helix, would move to a similar position to that in porcine DPIV. Consequently, it was expected that Tyr642 and Tyr646, which constitute the hydrophobic pocket, would change their positions to the corresponding residue positions in porcine DPIV from the original positions in Stenotrophomonas DPIV, closing in the pyrrolidine ring of a substrate. In conclusion, it is considered that displacement of the β-propeller domain affects the size of the hydrophobic pocket on the catalytic domain and that a conformational change of the hydrophobic pocket is an important factor in the activity of Stenotrophomonas DPIV toward substrates containing a Hyp residue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses run by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbot, C. A., G. W. McCaughan, and M. D. Gorrell. 1999. Two highly conserved glutamic acid residues in the predicted β propeller domain of dipeptidyl peptidase IV are required for its enzyme activity. FEBS Lett. 458278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad, S., L. Wang, and P. E. Ward. 1992. Dipeptidyl(amino)peptidase IV and aminopeptidase M metabolize circulating substance P in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2601257-1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth, A., H. Schulz, and K. Neubert. 1974. Purification and characterization of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV. Acta Biol. Med. Chem. 32157-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauvois, B. 1988. A collagen-binding glycoprotein on the surface of mouse fibroblasts is identified as dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochem. J. 252723-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauvais, A., M. Monod, J. Wyniger, J. P. Debeaupuis, E. Grouzmann, N. Brakch, J. Svab, A. G. Hovanessian, and J. P. Latge. 1997. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV secreted by Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungus pathogenic to humans. Infect. Immun. 653042-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjelke, J. R., J. Christensen, P. F. Nielsen, S. Branner, A. B. Kanstrup, N. Wagtmann, and H. B. Rasmussen. 2004. Tyrosine 547 constitutes an essential part of the catalytic mechanism of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Biol. Chem. 27934691-34697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristol, L. A., L. Finch, E. V. Romm, and L. Tacacs. 1992. Characterization of novel rat thymocyte costimulating antigen by monoclonal antibody 1.3. J. Immunol. 148332-338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. Delano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J.-S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, N. Nilges, N. S. Panni, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography and NMR System, a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandu, D., and D. Nandi. 2003. PepN is the major aminopeptidase in Escherichia coli: insights on substrate specificity and role during sodium-salicylate-induced stress. Microbiology 1493437-3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 50760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox, S. W., and B. M. Eley. 1989. Detection of cathepsin B- and L-, elastase-, tryptase-, trypsin-, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV-like activities in crevicular fluid from gingivitis and periodontitis patients with peptidyl derivatives of 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin. J. Periodontal Res. 24353-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de La Fortell, E., and G. Bricogne. 1997. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol. 276472-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denton, M., and K. G. Kerr. 1998. Microbiological and clinical aspects of infection associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1157-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel, M., T. Hoffmann, L. Wagner, M. Wermann, U. Heiser, R. Kiefersauer, R. Huber, W. Bode, H. U. Demuth, and H. Brandstetter. 2003. The crystal structure of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) reveals its functional regulation and enzymatic mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1005063-5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenn, T. D., D. Ringe, and G. A. Petsko. 2003. POVScript+: a program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36944-947. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischer, B. 1987. A novel pathway of human T cell activation via a 103 kD T cell activation antigen. J. Immunol. 1381346-1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frohmam, L. A., T. R. Downs, E. P. Heimer, and A. M. Felix. 1989. Dipeptidylpeptidase IV and trypsin-like enzymatic degradation of human growth hormone-releasing hormone in plasma. J. Clin. Investig. 831533-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulop, V., Z. Bocskei, and L. Polgar. 1998. Prolyl oligopeptidase: an unusual beta-propeller domain regulates proteolysis. Cell 94161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulop, V., Z. Szeltner, and L. Polgar. 2000. Catalysis of serine oligopeptidases is controlled by a gating filter mechanism. EMBO Rep. 1277-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulop, V., Z. Szeltner, V. Renner, and L. Polgar. 2001. Structures of prolyl oligopeptidase substrate/inhibitor complexes. Use of inhibitor binding for titration of the catalytic histidine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 2761262-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiramatsu, H., K. Kyono, Y. Higashiyama, C. Fukushima, H. Shima, S. Sugiyama, K. Inala, A. Yamamoto, and R. Shimizu. 2003. The structure and function of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV, possessing a unique eight-bladed β-propeller fold. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 302849-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm, L., and J. Park. 2000. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics 16566-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopsu-Havu, V. K., and G. G. Glenner. 1966. A new dipeptide naphthylamidase hydrolyzing glycyl-prolyl-β-naphthylamide. Histochemie 7197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito, K., Y. Nakajima, Y. Onohara, M. Takeo, K. Nakashima, F. Matsubara, T. Ito, and T. Yoshimoto. 2006. Aminopeptidase N (proteobacteria alanyl aminopeptidase) from Escherichia coli: crystal structure and conformational change of the methionine 260 residue involved in substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 28133664-33676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabashima, T., K. Ito, and T. Yoshimoto. 1996. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV from Xanthomonas maltophilia: sequencing and expression of the enzyme gene and characterization of the expressed enzyme. J. Biochem. 1201111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabashima, T., A. Kitazono, A. Kitano, K. Ito, and T. Yoshimoto. 1997. Prolyl aminopeptidase from Serratia marcescens: cloning of the enzyme gene and crystallization of the expressed enzyme. J. Biochem. 122601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabsch, W., and C. Sander. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 222577-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kantardjieff, K. A., and B. Rupp. 2003. Matthews coefficient probabilities: improved estimates for unit cell contents of proteins, DNA, and protein-nucleic acid complex crystals. Protein Sci. 121865-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieffer, T. J., C. H. McIntosh, and R. A. Pederson. 1995. Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagons-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology 1363585-3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitazono, A., T. Yoshimoto, and D. Tsuru. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and high expression of the proline iminopeptidase gene from Bacillus coagulans. J. Bacteriol. 1747919-7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuwahara, T., A. Yamashita, H. Hirakawa, H. Nakayama, H. Toh, N. Okada, S. Kuhara, M. Hattori, T. Hayashi, and Y. Ohnishi. 2004. Genomic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis reveals extensive DNA inversions regulating cell surface adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10114919-14924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski, R. M., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leslie, A. G. W. 1992. Recent change to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4+ESF-EAMCB Newsl. Protein Crystallogr., no. 26.

- 35.Longenecker, K. L., K. D. Stewart, D. J. Mardar, C. G. Jakob, E. F. Fry, S. Wilk, C. W. Lin, S. J. Ballaron, M. A. Stashko, T. H. Lubben, H. Yong, D. Pireh, Z. Pei, F. Basha, P. E. Wildeman, T. W. von Geldern, J. M. Trevilyan, and V. S. Stoll. 2006. Crystal structures of DPP-IV (CD26) from rat kidney exhibit flexible accommodation of peptidase-selective inhibitors. Biochemistry 457474-7482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews, B. W. 1968. Solvent content of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 33491-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayo, B., J. Kok, K. Venema, W. Bockelmann, M. Teuber, H. Reinke, and G. Venema. 1991. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 5738-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McRee, D. E. 1993. Practical protein crystallography, p. 386. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 39.Mentlein, R., B. Gallwits, and W. E. Schmidt. 1993. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagons-like peptide-1(7-36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur. J. Biochem. 213829-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merritt, E. A., and M. E. Murphy. 1994. Raster3D version 2.0. A program for photorealistic molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 50869-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monod, M., B. Lechenne, O. Jousson, D. Grand, C. Zaugg, R. Stochkin, and E. Grouzmann. 2005. Aminopeptidases and dipeptidyl-peptidases secreted by the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. Microbiology 151145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakajima, Y., K. Ito, M. Sakata, Y. Xu, K. Nakashima, F. Matsubara, S. Hatakeyama, and T. Yoshimoto. 2006. Unusual extra space at the active site and high activity for acetylated hydroxyproline of prolyl aminopeptidase from Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 1881599-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naush, I., and E. Heymann. 1985. Substance P in human plasma is degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase IV, not by cholinesterase. J. Neurochem. 441354-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogata, S., Y. Misumi, E. Tsuji, N. Takami, K. Oda, and Y. Ikehira. 1992. Identification of the active site residues in dipeptidyl peptidase IV by affinity labeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 312582-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oya, H., I. Nagatsu, and T. Nagatsu. 1972. Purification and properties of glycylprolyl-β-naphthylamidase in human submaxillary gland. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 258591-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piazza, G. A., H. M. Callanan, J. Mowery, and D. C. Hixson. 1989. Evidence for a role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in fibronectin-mediated interactions of hepatocytes with extracellular matrix. Biochem. J. 262327-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasmussen, H. B., S. Branner, F. C. Wiberg, and N. Wagtmann. 2003. Crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 in complex with a substrate analog. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1019-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarid, S., A. Berger, and E. Katchalski. 1959. Proline iminopeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2341740-1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shan, L., I. I. Mathews, and C. Khosla. 2005. Structural and mechanistic analysis of two prolyl endopeptidases: role of interdomain dynamics in catalysis and specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1023599-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shibata, Y., Y. Miwa, K. Hirai, and S. Fujimura. 2003. Purification and partial characterization of a dipeptidyl peptidase from Prevotella intermedia. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 18196-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szeltner, Z., D. Rea, V. Renner, V. Fulop, and L. Polgar. 2002. Electrostatic effects and binding determinants in the catalysis of prolyl oligopeptidase. Site specific mutagenesis at the oxyanion binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 27742613-42622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tachi, H., H. Ito, and E. Ichishima. 1992. An X-prolyl dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Phytochemistry 313707-3709. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terwilliger, T. C., and J. Berendzen. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 55849-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyagi, R., R. Lai, and R. G. Duggleby. 2004. A new approach to ‘megaprimer’ polymerase chain reaction mutagenesis without an intermediate gel purification. BMC Biotechnol. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vivier, I., D. Marguet, P. Naquet, J. Bonicel, D. Nlack, C. X. Li, A. M. Bernard, J. P. Gorvel, and M. Pierres. 1991. Evidence that thymocyte-activating molecule is mouse CD26 (dipeptidyl peptidase IV). J. Immunol. 147447-454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshimoto, T., and D. Tsuru. 1982. Proline-specific dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Flavobacterium meningoseptium. J. Biochem. 911899-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshimoto, T., and R. Walter. 1977. Post-proline dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV) from lamb kidney. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 485391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshimoto, T., T. Kita, M. Ichinose, and D. Tsuru. 1982. Dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV from porcine pancreas. J. Biochem. 92275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]