Abstract

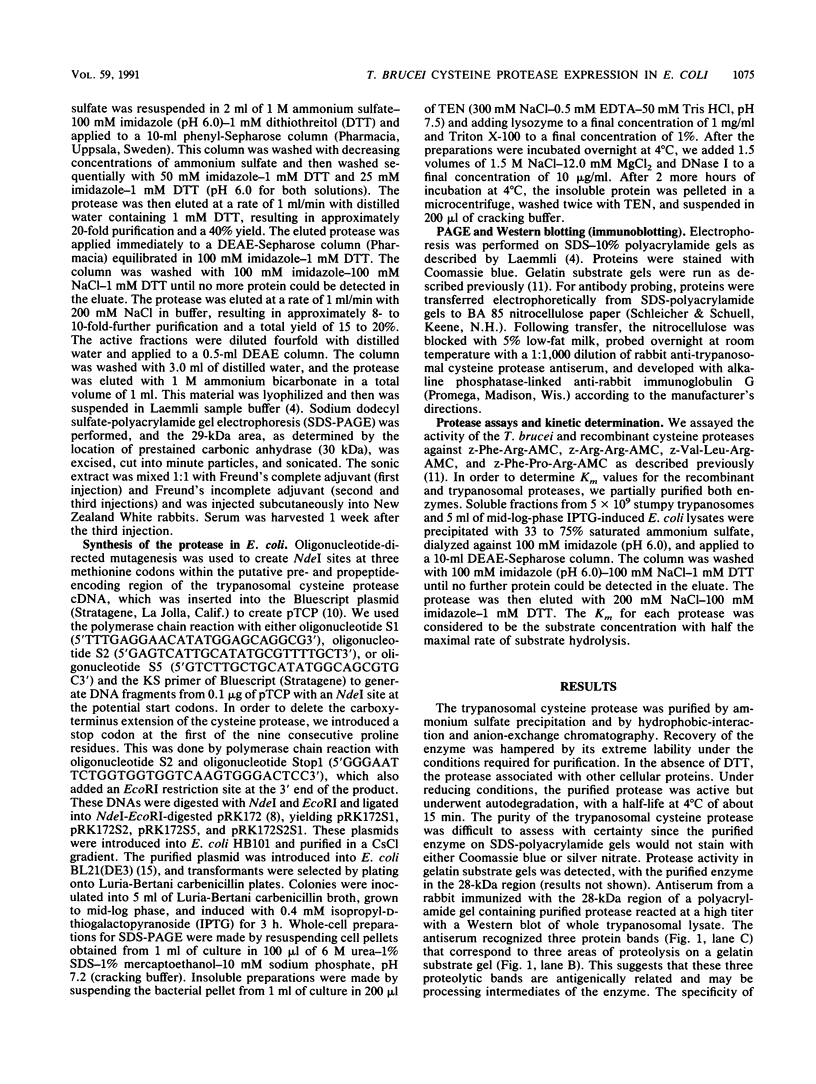

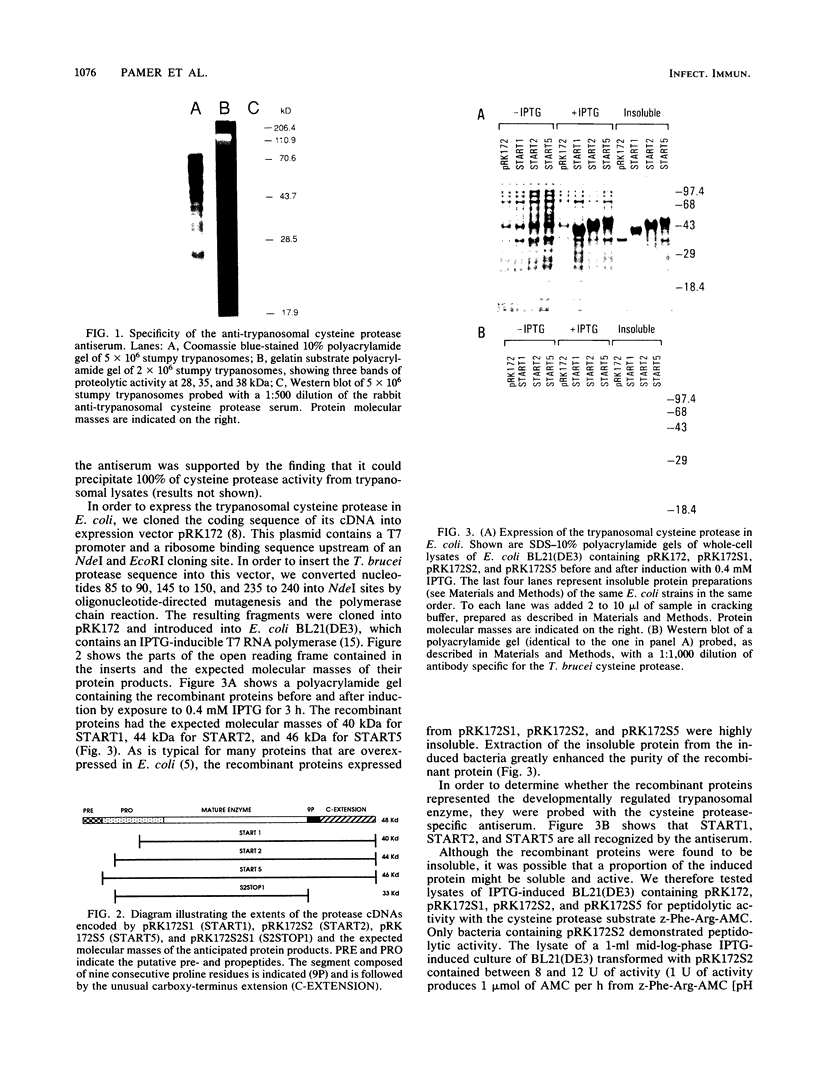

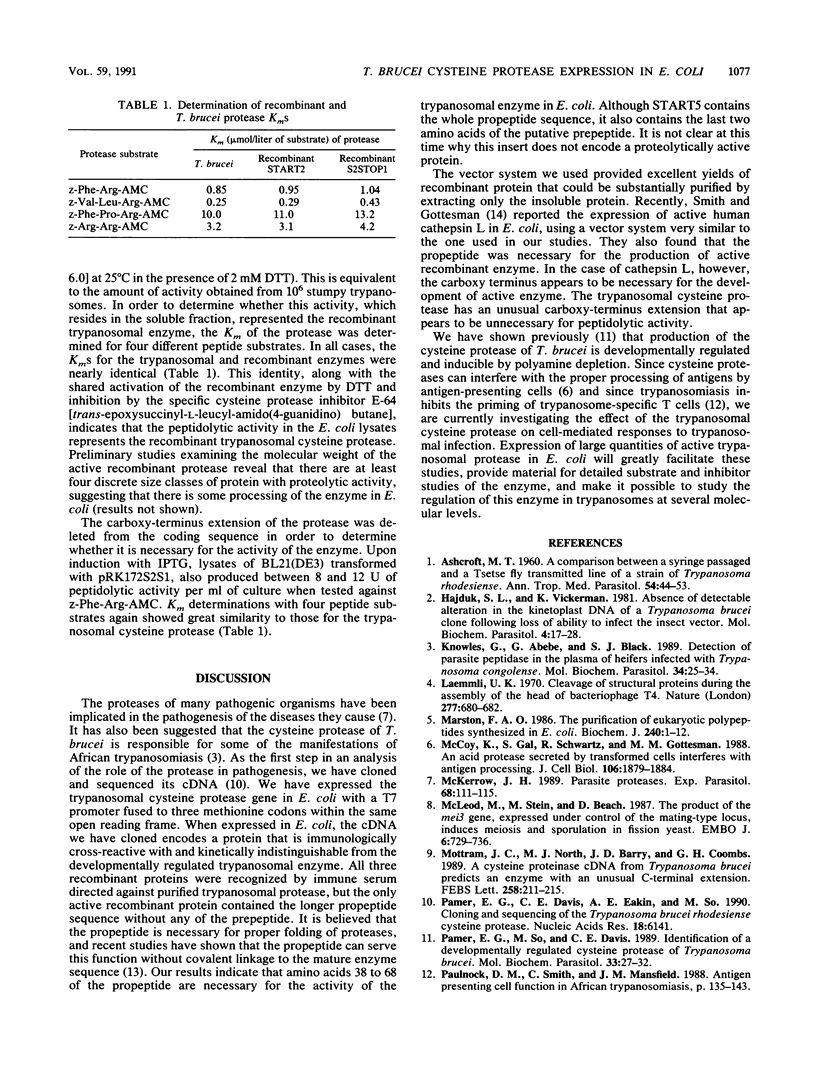

Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of African sleeping sickness, differentiates in the mammalian bloodstream from a long, slender trypanosome into a short, stumpy trypanosome. This event is necessary for infection of the tsetse fly and maintenance of the life cycle. We have previously shown that the stumpy form contains 10- to 15-fold-greater cysteine protease activity than either the slender form or the insect midgut procyclic, and we have isolated a cDNA encoding the protease. In order to determine whether the cDNA encodes the developmentally regulated cysteine protease, we have purified the protease from trypanosomes and have made a polyclonal antiserum against it. The trypanosomal protease gene was then expressed in Escherichia coli with three different methionines within the pre- and propeptides acting as initiation sites. In each case, a protein was synthesized that was recognized by an antiserum specific for the developmentally regulated trypanosomal cysteine protease. The protein synthesized from the more upstream initiation site within the propeptide was proteolytically active. The recombinant protease and the trypanosomal enzyme were identical with respect to peptide substrates and protease inhibitors. The protein remained active when synthesized in a truncated form lacking the nine consecutive prolines and carboxy-terminus extension, indicating that the terminal 108 amino acids are not necessary for proteolytic activity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ASHCROFT M. T. A comparison between a syringe-passaged and a tsetse-fly-transmitted line of a strain of Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1960 Apr;54:44–53. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1960.11685955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk S. L., Vickerman K. Absence of detectable alteration in the kinetoplast DNA of a Trypanosoma brucei clone following loss of ability to infect the insect vector (Glossina morsitans). Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1981 Nov;4(1-2):17–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(81)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles G., Abebe G., Black S. J. Detection of parasite peptidase in the plasma of heifers infected with Trypanosoma congolense. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989 Apr;34(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston F. A. The purification of eukaryotic polypeptides synthesized in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1986 Nov 15;240(1):1–12. doi: 10.1042/bj2400001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy K., Gal S., Schwartz R. H., Gottesman M. M. An acid protease secreted by transformed cells interferes with antigen processing. J Cell Biol. 1988 Jun;106(6):1879–1884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerrow J. H. Parasite proteases. Exp Parasitol. 1989 Jan;68(1):111–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod M., Stein M., Beach D. The product of the mei3+ gene, expressed under control of the mating-type locus, induces meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1987 Mar;6(3):729–736. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram J. C., North M. J., Barry J. D., Coombs G. H. A cysteine proteinase cDNA from Trypanosoma brucei predicts an enzyme with an unusual C-terminal extension. FEBS Lett. 1989 Dec 4;258(2):211–215. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamer E. G., Davis C. E., Eakin A., So M. Cloning and sequencing of the cysteine protease cDNA from Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Oct 25;18(20):6141–6141. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamer E. G., So M., Davis C. E. Identification of a developmentally regulated cysteine protease of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989 Feb;33(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silen J. L., Agard D. A. The alpha-lytic protease pro-region does not require a physical linkage to activate the protease domain in vivo. Nature. 1989 Oct 5;341(6241):462–464. doi: 10.1038/341462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Gottesman M. M. Activity and deletion analysis of recombinant human cathepsin L expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989 Dec 5;264(34):20487–20495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W., Moffatt B. A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986 May 5;189(1):113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman K. Developmental cycles and biology of pathogenic trypanosomes. Br Med Bull. 1985 Apr;41(2):105–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman K. Polymorphism and mitochondrial activity in sleeping sickness trypanosomes. Nature. 1965 Nov 20;208(5012):762–766. doi: 10.1038/208762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]