Abstract

Fuller et al. (Reports, 23 May 2008, p. 1074) reported that the dorsomedial hypothalamus contains a Bmal1-based oscillator that can drive food-entrained circadian rhythms. We report that mice bearing a null mutation of Bmal1 exhibit normal food-anticipatory circadian rhythms. Lack of food anticipation in Bmal1−/− mice reported by Fuller et al. may reflect morbidity due to weight loss, thus raising questions about their conclusions.

Daily cycles of food availability have a powerful influence on circadian organization of behavior and physiology in mammals. Regular mealtimes induce food-anticipatory behavioral rhythms with circadian properties similar to those of light-entrainable rhythms (1, 2)and set the phase of circadian oscillators in most peripheral organs (3). The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the site of the circadian pacemaker that mediates light-entrainable rhythms, but it is not required for the generation of food-anticipatory rhythms.

Fuller et al. (4) reported that targeted null mutation of the canonical circadian clock gene Bmal1 eliminates both light-entrainable and food-anticipatory rhythms in mice. Virally mediated rescue of Bmal1 limited to the SCN selectively restored light-entrainable circadian rhythms in these mice, whereas rescue limited to the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH) selectively restored food-anticipatory rhythms of activity and body temperature. This work builds on an earlier report from the same laboratory that partial DMH lesions induced by the excitotoxin ibotenic acid attenuate or eliminate food-anticipatory rhythms in rats fed a single daily meal during the usual rest phase of the circadian sleep-wake cycle (5). Others have shown that the DMH (among a number of brain regions) expresses daily rhythms of circadian clock gene expression synchronized by scheduled feeding (6), although this is related to caloric restriction and not to food-anticipatory rhythms per se (7). Fuller et al.(4) interpreted their results to indicate that the DMH is the site of the long-sought food-entrainable circadian pacemaker for behavior.

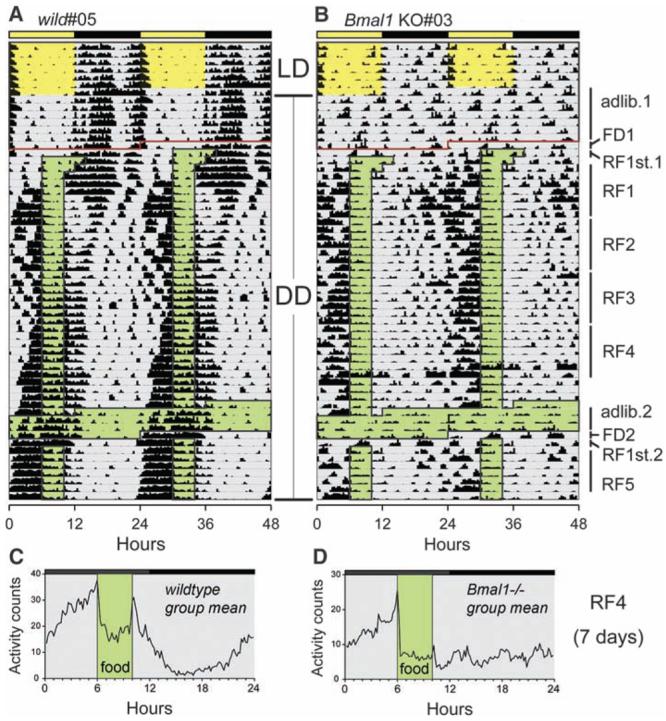

We question the evidence and dispute the conclusion that food-anticipatory behavioral rhythms are driven by a Bmal1-dependent circadian pacemaker in the DMH. Our laboratories have also conducted extensive analyses of food restriction in Bmal1−/− mice and have found no deficit in the expression of food-anticipatory activity rhythms, either in a standard light-dark (LD) cycle, in constant dark, or during one or two cycles of fasting after scheduled feeding in LD. Similar results have been presented recently (8). As illustrated in Fig. 1, Bmal1−/− mice in constant dark exhibit unambiguous, robust food-anticipatory activity to a daily 4-hour meal. Group mean average waveforms reveal anticipatory rhythms of similar timing and magnitude in wild-type (Fig. 1C) and Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 1D). None of the Bmal1−/− failed to anticipate mealtime.

Fig. 1.

Activity rhythms of wild-type (A) and Bmal1−/− (B) mice (17). Each line represents 48 hours, plotted in 20-min bins from the left. Consecutive days are also aligned vertically, that is, the charts are double-plotted. Activity was measured by passive infrared motion sensors mounted 30 cm above each cage. Activity data were normalized to the daily mean and are represented by heavy bars, in quartile heights. During the first 14 days, food was available ad libitum, for 7 days in LD (12-hour photoperiod denoted by yellow shading) and 7 days in constant dark (gray shading). Food restriction schedules began after the horizontal red line and were conducted in constant dark. After 30 hours of food deprivation (FD1), food was available for 8 hours (RF1st.1), then reduced to 6 hours and 4 hours over the next 2 days, respectively. RF1-5 denotes 7-day blocks of 4 hour/day feeding (green shading). Blocks RF4 and 5 are separated by 4 days of ad-lib feeding (green shading) and 30 hours of food deprivation (FD2). (C and D) Group activity profiles from wild-type mice (n = 4) and Bmal1−/− mice (n = 5), respectively, averaged in 10-min bins over days 22 to 28 (block RF4) of restricted feeding in constant dark. Green shading denotes the 4-hour daily mealtime.

Why food-anticipatory rhythms appear to be severely affected by Bmal1 knockout in Fuller et al.(4) is uncertain but may be related to how the mice were fed. Mice in that study were maintained on a single 4-hour daily meal. The standard procedure for studying food-anticipatory rhythms in mice (as opposed to rats) is to gradually reduce the duration of food availability over several days or more, to prevent excessive weight loss. Bmal1−/− mice appear particularly vulnerable to restricted feeding schedules, likely due in part to impaired glucose homeostasis (9) and reduced mobility caused by progressive, noninflammatory arthropathy (10). If food availability is abruptly limited to 4 hours per day, mortality rates in Bmal1−/− mice approach 80% (11). In preliminary work, we also observed inadequate food intake in Bmal1−/− mice during time-limited feeding schedules if chow pellets were provided in overhead food hoppers rather than on the cage floor. Fuller et al. (4) did not report mortality or body weight data but did note that mutant mice “often slept or were in torpor through the window of [food availability], requiring us to arouse them by gentle handling after presentation of food to avoid their starvation and death.” Torpor is not a natural state in wild-type mice of this strain and was not apparent in our studies or in the study of Storch and Weitz (8, 11), in which Bmal1−/− mice were appropriately adapted to time-limited feeding. Notably, Bmal1−/− mice in these studies appeared healthy and exhibited clear food anticipation. We suggest that the food-restriction procedure used by Fuller et al. was too severe and that the lack of food anticipation in their Bmal1−/− mice was an artifact of morbidity.

The DMH lesion results previously reported by the Saper laboratory (5) also differ from those obtained in other laboratories. Three studies have shown no deficit in food anticipation after complete DMH ablation by radio-frequency lesions, in either rats in LD (12, 13), or mice in LD or constant dark (14). A fourth study has confirmed that excitotoxic DMH lesions (unlike radio-frequency lesions) may attenuate anticipation of a mid-day meal, but that robust food-anticipatory rhythms are revealed immediately (i.e., are unmasked) by subsequent ablation of the SCN (15). Clearly, the DMH is not required for the generation of food-anticipatory rhythms, although it may participate by inhibiting outputs from the SCN that normally promote sleep during the day and that pass through the medial hypothalamic area destroyed by radio-frequency DMH lesions.

Fuller et al.(4) suggest that rodents lacking a food-entrainable pacemaker (by lesion or knockout) might anticipate a mid-day meal by associating food with lights. The results presented here and elsewhere (8) demonstrate that LD cues are not necessary for food anticipation in Bmal1−/− mice. Previous work has shown that food anticipatory rhythms in rats are not affected by shifting or eliminating the LD cycle (1, 2) and that external cues actually delay the onset and reduce the magnitude of anticipatory rhythms [e.g., (16)]. Moreover, given the similarity of food anticipatory rhythms in DMH-ablated rats and intact controls [e.g., (10, 12)], the argument that these animals anticipate a daily meal by radically different timing mechanisms (i.e., associative learning or interval timing versus entrainment of a circadian oscillator) seems implausible.

The clear preservation of food-anticipatory behavioral rhythms in Bmal1−/− mice and in DMH-ablated rats indicates that the molecular and neural bases for these rhythms remain to be established.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid (19659072) for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Technology of Japan to T.T. W.N. is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. S.Y. was supported by NIH NS051278. R.E.M. was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. We thank C. Bradfield, University of Wisconsin, for supplying Bmal−/− mice.

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/322/5902/675a/DC1 Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.Stephan FK. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2002;17:284. doi: 10.1177/074873040201700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mistlberger RE. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1994;18:171. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schibler U, Ripperger J, Brown SA. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2003;18:250. doi: 10.1177/0748730403018003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller PM, Lu J, Saper CB. Science. 2008;320:1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1153277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gooley JJ, Schomer A, Saper CB. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:398. doi: 10.1038/nn1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mieda M, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Tanaka K, Yanagisawa M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604189103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verwey M, Khoja J, Stewart J, Amir S. Neuroscience. 2007;147:277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storch K-F, Weitz CJ. Proc. Soc. Res. Biol. Rhythms. 2008;11:202. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudic RD, et al. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunger MK, et al. Genesis. 2005;41:122. doi: 10.1002/gene.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storch K-F, Weitz CJ. personal communication.

- 12.Landry GJ, Simon M, Webb IC, Mistlberger RE. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;290:R1527. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00874.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry GJ, Yamakawa GR, Webb IC, Mear RJ, Mistlberger RE. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2007;22:484. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriya T, et al. Proc. 2nd World Cong. Chronobiol; 2007. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acosta-Galvan G, Moro Chao H, Escobar-Briones C, Buijs RM. Proc. Soc. Res. Biol. Rhythms. 2008;11:199. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terman M, Gibbon J, Fairhurst S, Waring A. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1984;423:470. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Materials and Science methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.