Abstract

Background

Adolescent depression is both a major public health and clinical problem, yet primary care physicians have limited intervention options. We developed two versions of an Internet-based behavioral intervention to prevent the onset of major depression and compared them in a randomized clinical trial in 13 US primary care practices.

Methods

We enrolled 84 adolescents at risk for developing major depression and randomly assigned them to two groups: brief advice (BA; 1–2 minutes) + Internet program versus motivational interview (MI; 5–15 minutes) + Internet program. We compared pre/post changes and between group differences for protective and vulnerability factors (individual, family, school and peer).

Results

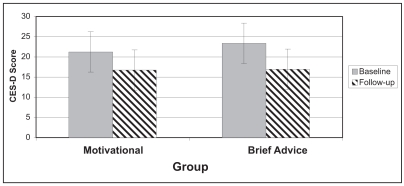

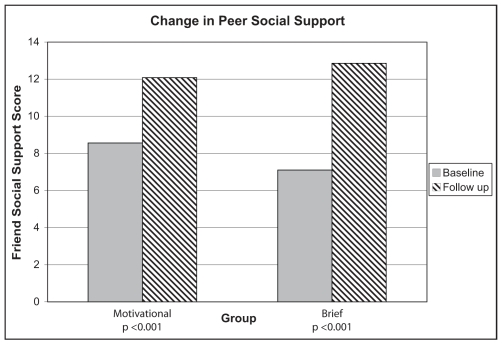

Compared with pre-study values, both groups demonstrated declines in depressed mood; [MI: 21.2 to 16.74 (p < 0.01), BA: 23.34 to 16.92 (p < 0.001)]. Similarly, both groups demonstrated increases in social support by peers [MI: 8.6 to 12.1 (p = 0.002), BA: 7.10 to 12.5 (p < 0.001)] and reductions in depression related impairment in school [MI: 2.26 to 1.76 (p = 0.06), BA: 2.16 to 1.93 (p = 0.07)].

Conclusions

Two forms of a primary care/Internet-based behavioral intervention to prevent adolescent depression may lower depressed mood and strengthen some protective factors for depression.

Keywords: depressive disorder, adolescents, prevention, Internet, primary care, intervention

Résumé

Contexte

Bien que la dépression des adolescents soit à la fois un problème majeur pour la santé publique et les services cliniques, les interventions des médecins de première ligne sont limitées. Deux versions d’un programme d’intervention comportementale sur Internet destiné à prévenir l’apparition des symptômes de dépression grave ont été comparées lors d’un essai clinique aléatoire mené dans 13 centres de soins de première ligne aux États-Unis.

Méthodologie

Quatre-vingt-quatre adolescents à risque de dépression grave ont été répartis de manière aléatoire en deux groupes: un groupe recevait de brefs conseils (BC: 1–2 minutes) et suivait le programme de prévention de la dépression sur Internet ; l’autre groupe participait à des sessions d’entrevue motivationnelle (EM: 5–15 minutes) et suivait le programme de prévention de la dépression sur internet. Nous avons comparé les changements constatés dans les facteurs de protection et de vulnérabilité (individuels, familiaux, scolaires et relations avec les pairs).

Résultats

La comparaison des données avant l’essai indiquait, pour les deux groupes, une baisse dans l’humeur dépressive; [EM: de 21,2 à 16.74 (p < 0,01); BC: de 23,34 à 16.92 (p < 0,001)]. De même, les deux groupes affichaient une hausse dans le soutien social par les pairs [EM: de 8,6 à 12,1 (p = 0,002); BC: de 7,10 à 12,5 (p < 0,001)] et une baisse du handicap scolaire lié à la dépression [EM: de 2,26 à 1,76 (p = 0,06) ; BC: de 2,16 à 1,93 (p = 0,07)].

Conclusion

Les deux formes d’intervention comportementale en première ligne/sur Internet conçues pour prévenir la dépression des adolescents font diminuer le nombre de sujets souffrant d’humeur dépressive et renforcent certains facteurs de protection contre la dépression.

Keywords: trouble dépressif, adolescents, prévention, Internet, première ligne, intervention

Introduction

Depression is the most common mental disorder in adolescence with 8–10% of adolescents experiencing an episode each year (Kessler & Walters, 1998). Depression is a recurrent chronic disorder with a substantial adverse impact on social, educational, and health outcomes during adolescence and beyond (Hankin, 2006). Even with treatment, 30–40% of depressed adolescents fail to attain full remission (March et al., 2004). Increasingly, primary care physicians are expected to screen and intervene for depressive episodes in adolescents (Richardson & Katzenellenbogen, 2005; Zuckerbrot et al., 2007). However, many primary care physicians have concerns about prescribing anti-depressant medications to adolescents. Availability of high quality mental health specialty care for children is often limited by scarcity of providers in many geographic areas and/or cost containment strategies of managed behavioral health organizations (Grembowski et al., 2002; Sturm, Ringel, & Andreyeva, 2003; Van Voorhees, Wang, & Ford, 2003). One way of addressing these difficulties would be to develop a depression prevention intervention for primary care physicians.

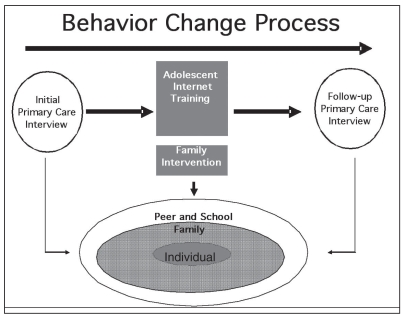

CATCH-IT (Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive-behavioral and Interpersonal Training, Figure 1) was developed as a low cost, easily disseminated preventive intervention for primary care environments and demonstrated favorable trends in three vulnerability factors in a pilot study (Van Voorhees, Ellis, Stuart, Fogel, & Ford, 2005). Adolescent adherence to mental health treatments is known to vary in consistency and reliability (Asarnow, Jaycox, & Anderson, 2002) and adolescent participation in Internet interventions is often inconsistent (Clarke, 2002; Santor, Poulin, LeBlanc, & Kusumakar, 2007). With this in mind, we sought to determine what form of engagement and amount of physician time is required to effectively engage youth in an Internet-based preventive program. Brief advice (BA) and motivational interviewing (MI), two primary care based approaches to behavior change, are possible methods of engagement. They vary considerably in terms of time (1–2 minutes versus 5–15 minutes), training requirements, and cost/feasibility.

Figure 1:

Intervention Model

The purpose of this study is to determine which primary care approach is more efficacious in reducing vulnerability of major depressive disorder as measured by pre/post changes in vulnerability factors. Our first hypothesis was that the MI would enhance willingness to prevent depressive disorder while the BA would not. The second hypothesis was that MI would be more effective in combination with the Internet intervention in reducing ambient depressed mood. In the third hypothesis, we proposed that MI would be superior in demonstrating a greater pre/post changes in vulnerability and protective factors such as social support and automatic negative thoughts. We conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing MI + Internet prevention intervention versus BA + Internet prevention intervention in terms of ratings of perceived helpfulness and motivation, depressed mood, vulnerability, and protective factors.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing BA + Internet program versus MI + Internet program. This was a phase II clinical trial focused on determining the optimal primary care exposure to maximize benefit in preparation for a phase III efficacy trial whereby the optimal intervention would be compared to a treatment as usual control. We recruited 13 primary care practice sites within five different health systems in four states (US Midwest and South). Practices were directly called or contacted through physician leaders within health care systems. Practices could elect either to have their own physicians conduct the interview (N=10 practices) or to have the study principle investigator (primary care physician, N=3 practices) conduct the interview. We evaluated a self-administered post-study questionnaire at 4–8 weeks. All protocols had IRB approval.

Adolescent Recruitment

Recruitment occurred from February to November 2007. The screening instrument was a two-item questionnaire based on the Patient Health Questionnaire Adolescent (PHQ-A) core depression symptom items (Johnson, Harris, Spitzer, & Williams, 2002). Those reporting any core depressive symptom (depressed mood, loss of pleasure or irritability) of depressive disorder lasting a minimum of a few days in the last two weeks were considered positive screens. Study staff contacted those with positive screens who granted permission (and parent if participant was below age 18) by phone to conduct an eligibility assessment which included the full PHQ-A assessment.

Adolescent Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were between the ages of 14–21 years and experienced persistent sub-threshold depression (> 1 core symptoms of depression) at both the screening and eligibility assessment (1–2 weeks after initial screening). Exclusion criteria included meeting criteria (or undergoing active treatment) for major or minor depression, expressing frequent suicidal ideation or intent, or meeting criteria for the following: bipolar, conduct, substance abuse, generalized anxiety, panic, or eating disorders. Individuals who reported symptoms of conduct disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or past substance abuse were not excluded. Primary care physicians were granted some discretion in enrolling individuals with borderline major depression and/or generalized anxiety disorder.

Primary Care Intervention and Training

We trained physicians in one hour programs using a lecture and example video tapes. In the BA condition (1–2 minute interview), the physician advises the adolescent that the adolescent is experiencing a depressed mood, that the adolescent should go to the website and complete the intervention, and that the adolescent should have a follow-up visit and interview in 4–6 weeks. In the MI (5–15 minutes interview), the physician helps the adolescent identify a personal rationale for completing the Internet program by facilitating the adolescent’s development of favorable attitudes towards participation and completion of the intervention. The adolescent in the MI group also receives three motivational phone calls from a social worker case manager, who received a similar course of training in MI.

Internet Intervention

The intervention included 14 Internet-based modules based on Behavioral Activation and Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy (CBT) (Clarke, 1994; Jacobson, 2001), Interpersonal Psychotherapy techniques (Mufson, 2004; Stuart, 2003) and a community resiliency concept. (Bell, 2001) To develop the intervention, we employed evidence-based interventions of established efficacy based on established principles of effective community-based preventive interventions (Nation et al., 2003). CATCH-IT teaches adolescents how to reduce behaviors that increase vulnerability for depressive disorders (e.g., procrastination, avoidance, rumination, pessimistic appraisals, and indirect communication style) and increase behaviors that are thought to protect against depressive disorder (e.g., behavioral scheduling, countering pessimistic thoughts, activating social networks, and strengthening relationship skills). We also provided a parent workbook to the parents of adolescents under age 18. This workbook focused on supporting the development of resiliency in the adolescent (Beardslee, Gladstone, Wright, & Cooper, 2003), understanding the relationship between depressed mood in the adolescent and other family members, and building family resiliency. This intervention was extensively revised based on results and feedback from an initial pilot study (Van Voorhees et al., 2007).

Internet Intervention Structure

We employed instructional design theory (Briggs, Briggs, Gagne, & Wager, 1992) to actively engage adolescents in reducing vulnerability/enhancing protective factors (Reinecke & Simmons, 2005). Instructional design intends to 1) gain attention of the learner, 2) inform the learner of objectives, 3) strengthen recall of essential knowledge, 4) provide needed stimulus material, 5) offer learning guidance, 6) measure performance, 7) offer feedback on performance correctness, 8) evaluate performance, and 9) increase transfer and retention (Briggs et al., 1992). In the intervention, each module included learning goals, review, core concept explanation, adolescent stories to illustrate the lessons, skill building exercises, a summary, feedback on the experience and an Internet-based reward. After providing the core concepts, we stimulated recall, understanding and retention with narratives (“teen stories”) based on the principles of vicarious learning theory that illustrated the concept in realistic situations and reflection exercises (Briggs et al., 1992). The teen stories were written in first person or intimate third person style so as to connect directly with the experience of the reader. The Internet site is open for public viewing at http://catchit.bsd.uchicago.edu.

Consent, Enrollment, and Randomization

Following a positive screening, adolescents (and their parents if applicable) underwent the informed consent process. Participants were randomized by sealed envelope (blocked by physician in physician interview practices and by gender in principal investigator interviewer practices). Participants were assigned a private username and access code to allow them to enter the Internet website. Participants could not be blinded to group assignment, but the two groups were described as “long” and “short” interviews with equal access to the Internet website.

Fidelity Assessment

We report fidelity to the interview model and adherence to the Internet intervention for both groups. We selected 13 taped interviews from each condition and two raters reviewed them based on a standard assessment instrument (conflicts resolved by consensus). We report the percentage visiting the site, mean time on site, number of modules visited, percentage of exercises completed, number of characters typed, number of safety phone calls, and the number of motivational calls.

Data Collection

Baseline questionnaires were completed before any study intervention was received, except in the case where time restraints required the adolescent to take it home for completion. Follow-up was completed between 4–8 weeks after enrollment. In a few cases, follow-up occurred several months later. Because of wide dispersion of clinics, adolescent reluctance to complete lengthy questionnaires and voluntary cooperation of primary care clinic staff, some post-study data collection was incomplete. A clerical error omitted some items for several vulnerability instruments from the questionnaires of several participants. Additionally, phone assessments of mood and depressive disorder were done at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

Sample Characteristics

We obtained information on age, ethnicity, birth order, parents marital status, living situation, years of school completed (by adolescent and each parent). We also asked, “Have you ever been treated (with medication or counseling) for depression?” and “Have any of your family members (mother, father, sister, brothers) ever been treated for depression that lasted at least four weeks?” We also report the percentage with a depressive disorder and mean symptoms scores.

Study Outcomes

Individual Vulnerability and Protective Factors

We collected baseline and follow-up assessments of individual vulnerability and protective factors including symptoms of other mental disorders, mood and affect regulation, cognition and self-efficacy. To assess motivation, we used ratings from standard assessments of importance, self-efficacy, readiness for change, and stages of change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). For symptoms of other mental disorders, we asked questions (yes/no responses) with regard to generalized anxiety (In the past four weeks, have you been very anxious, nervous or panicky?), panic disorder symptoms (In the past four weeks, have you had an episode or spell when you had the sudden panic?), and problem drinking (In the last month, have you “had > five drinks/day?” or “been drinking more than usual?”). Regarding mood and affect regulation, we report Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D, 20 item scale) scores (Radloff, 1991), CES-D subscales (e.g., depressed mood, somatic, happy, and interpersonal) and moodiness frequency (“How often have you felt moody in last 12 months?”, 0=never to 3=almost all the time). If the post study self-administered survey CES-D score was not available, we used the CES-D score from the 6 week phone call, N=9). Regarding cognition, we report Automatic Negative Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised (Kendall, 1989) and self-efficacy (1=strongly agree to 4=strongly disagree, higher number on scales indicates greater self-efficacy) (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981). Items in each category were obtained from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADHEALTH), in which these items predicted future risk of depressive disorder (Van Voorhees et al., 2008). These items include: self-rated health (“In general how is your health?” with 1=excellent to 5=poor) self-rated intelligence (1=below to 6=above average) and problem-solving skills (rational solving, 0=never to 3=nearly all the time) and self-efficacy with regard to affect regulation through behavior change (“I can change my depression by changing my behavior,” 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

Family, Peer and School, Vulnerability and Protection

Adolescents reported the level of perceived family social support (Procidano & Heller, 1983) and rated closeness to “Mom” and “Dad” and level of desire to leave home (1=not at all to 5=quite a bit) in items used in the ADHEALTH questionnaire (Van Voorhees et al., 2008). Adolescents rated perceived peer social support (Procidano & Heller, 1983) and from the ADHEALTH survey, items with regard to social acceptance (“I feel socially accepted”), and closeness to classmates (I feel close to people at my school) (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree). Additionally, we report level of school impairment related to depressed mood, based on items derived from the ADHEALTH survey and interviews with emerging adults (Kuwabara, Van Voorhees, Gollan, & Alexander, 2007). These items included reports of most recent grades and agreement with the stem statement, “Feeling down or sad has affected my ability to do well in school” in the following ways (such as “concentrating in class” or “getting along with teachers,” with 1=not at all to 4=a lot). The items with regard to impairment were combined into a scale as described below. Adolescents reported their most recent grades (1=A to 4=D or lower) in English and Math.

Statistical Analysis

We compared outcomes between baseline and post-study within randomized groups and between randomized groups at the same time points in a per-protocol analysis. For categorical outcomes, we used the McNemar’s test (and when relevant of fewer than 5 observations per cell, the exact version of the McNemar’s test) to compare repeat measures within the same group and as appropriate the Pearson chi square test or the Fisher’s exact test for between group comparisons. For continuous outcomes, we used paired t-tests to compare repeat measures and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare between the groups. Results are reported for all participants who completed the study and relevant items using a per-protocol analysis. The Mann-Whitney test was used when comparing non-parametric data. We report the number of individuals available for analysis in the second column of the tables. Scales were generated by creating a summative score for all the variables in the scale if at least half of the items had been responded to.

Evaluation of Missing Data

We completed several analyses to evaluate the effect of missing data. We compared non-responders (either to the post-study survey or to the social support questionnaire) by age, ethnicity, educational level, parent education, parent marital status, past treatment for depression, and baseline CES-D score. To determine if non-responders were less likely to experience improvement in depression symptoms, we compared post-study CES-D scores and change in CES-D scores between responders and non-responders. Finally, we completed analyses again using the last observation carried forward to determine if missing values might change interpretation of key results (Baron, Ravaud, Samson, & Giraudeau, 2008).

Results

Demographics

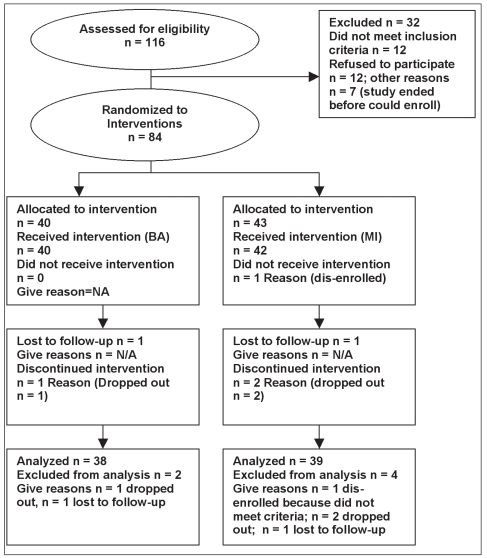

We enrolled 84 individuals (MI, N=44; BA, N=40) and follow-up data were available for mood on 77/84 (91%), and 72/84 (86%) completed at least part of the post-study questionnaire (Figure 2). The sample included significant ethnic minority representation (37%) and was divided approximately equally by gender (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups at baseline.

Figure 2:

CONSORT Diagram

Table 1:

Sample Characteristics

| Charactersitic | All Baseline Percentage | Number | Motivational Baseline Percentage | Number | Brief Advice Baseline Percentage | Number | Group Comparison P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.83 | ||||||

| Male | 43.82 | 36 | 44.19 | 19 | 42.5 | 17 | |

| Female | 56.18 | 47 | 55.81 | 24 | 57.5 | 23 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.56 | ||||||

| White | 57.83 | 48 | 59.52 | 26 | 62.16 | 23 | |

| Black | 22.89 | 19 | 19.05 | 8 | 29.73 | 11 | |

| Hispanic | 4.82 | 4 | 7.14 | 3 | 2.7 | 1 | |

| Asian | 5.68 | 5 | 5.68 | 4 | 2.7 | 1 | |

| Native American | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | |

| Other | 3.75 | 3 | 3.41 | 1 | 2.70 | 1 | |

| Age (mean and SD) | 17.44 | 2.04 | 17.05 | 2.02 | 17.90 | 2.02 | 0.89 |

| Family Information | |||||||

| First born | 46.25 | 37 | 45.24 | 19 | 48.65 | 19 | 0.76 |

| Parents Marital Status | 0.72 | ||||||

| Married | 56.41 | 56.41 | 59.52 | 25 | 50 | 18 | |

| Divorced | 19.23 | 19.23 | 21.43 | 9 | 19.44 | 7 | |

| Separated | 0 | 0 | 2.38 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | |

| Widowed | 2.56 | 2.56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Never Married | 21.79 | 21.79 | 16.67 | 7 | 27.78 | 10 | |

| Teen Living Situation | 0.12 | ||||||

| At home with Parents | 68.75 | 55 | 61.9 | 26 | 76.32 | 29 | |

| Alone | 2.5 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.26 | 2 | |

| With Friends or Roommates | 18.75 | 15 | 26.19 | 11 | 10.53 | 4 | |

| Other | 10 | 8 | 11.9 | 5 | 7.89 | 3 | |

| Father's Education | 0.12 | ||||||

| High School at least 2 years | 6.76 | 5 | 2.63 | 1 | 11.43 | 4 | |

| Finished high school | 33.78 | 25 | 26.32 | 10 | 40 | 14 | |

| College at least 2 years | 12.16 | 9 | 18.42 | 7 | 5.71 | 2 | |

| Finished college | 47.3 | 35 | 52.63 | 20 | 42.86 | 15 | |

| Mother's Education | 0.99 | ||||||

| High School at least 2 years | 6.58 | 5 | 7.69 | 3 | 5.56 | 2 | |

| Finished high school | 27.63 | 21 | 25.64 | 10 | 27.78 | 10 | |

| College at least 2 years | 26.32 | 20 | 28.21 | 11 | 25 | 9 | |

| Finished college | 39.47 | 30 | 38.46 | 15 | 41.67 | 15 | |

| Teen's Education | 0.92 | ||||||

| High School at least 2 years | 57.53 | 42 | 57.89 | 22 | 60 | 21 | |

| Finished high school | 13.7 | 10 | 13.16 | 5 | 11.43 | 4 | |

| College at least 2 years | 27.4 | 20 | 28.95 | 11 | 25.71 | 9 | |

| Finished college | 1.37 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.86 | 1 | |

| Depression History | |||||||

| History of depression treatment | 27.5 | 22 | 26.19 | 11 | 29.73 | 11 | 0.73 |

| Prior Counseling | 30.77 | 24 | 24.39 | 10 | 38.89 | 14 | 0.11 |

| Prior Medication | 17.81 | 13 | 16.22 | 6 | 19.44 | 7 | 0.72 |

| Family history of depression | 29.87 | 23 | 22.5 | 9 | 38.89 | 14 | 0.17 |

| Depressive Disorder | |||||||

| Depressive disorder (any) | 11.69 | 9 | 13.16 | 5 | 10.53 | 4 | 1 |

| Major Depression | 3.90 | 3 | 2.63 | 1 | 5.26 | 2 | 0.58 |

| Minor Depression | 8.80 | 6 | 10.53 | 4 | 5.30 | 2 | 0.38 |

| Dysthymia | 1.33 | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.31 |

Assessment of Interview Fidelity and Internet Participation

Physician adherence to the MI scripts was excellent with very little contamination of the BA condition with MI elements (MI and BA significantly differed with regard to MI ratings, Table 2). There was a nonsignficant trend toward greater levels of participation on the Internet site by those in the MI group (i.e., visiting site 90.7% versus 77.5%, p = 0.13 and time onsite 143 minutes (SD=108.1) versus 98.4 minutes (SD=124.6) p = 0.08).

Table 2:

Intervention Adherence and Fidelity

| Motivational

|

Brief Advice

|

P-value

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/(Percent) | SD/(N) | Mean/(Percent) | SD/(N) | Comparison | |

| Interview | |||||

| Motivational Interview Fidelity Rating Scale (alpha=0.90) | 4.21 | 0.8 3 | 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.003 |

| Interview Length (minutes) | 5.96 | 1.90 | 1.79 | 0.45 | 0.002 |

| Percentage visiting the site | (90.7) | (38) | (77.5) | (31) | 0.130 |

| Mean time on site (minutes) | 143.70 | 109.05 | 98.40 | 124.60 | 0.020 |

| Number of modules completed | 7.00 | 5.70 | 5.28 | 6.00 | 0.160 |

| Percentage of exercises completed | (61) | (37) | (67) | (23) | 0.110 |

| Number characters typed in to exercises | 3532.74 | 2985.27 | 1915.90 | 2326.00 | 0.004 |

| Telephone calls | |||||

| Number safety calls | 2.08 | 1.09 | 2.11 | 0.94 | 0.600 |

| Number motivational calls | 2.23 | 0.92 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Individual Vulnerability and Protective Factors

Depressed mood declined significantly in both groups while motivation only increased in the MI group (Tables 3, 4 and 5). There was a significant increase in all ratings of motivation (importance, self-efficacy, and readiness) and in stage of change for the MI, but not BA group (Tables 4 and 5). The percentage of those reporting symptoms of panic disorder and generalized anxiety symptoms (borderline significance) declined significantly in the BA group but not in the MI group. Depressed mood declined significantly in both groups (Figure 3 and Tables 3, 4, and 5) with moderate pre/post effect sizes (MI: effect size −0.44, 95% CI: −0.88, 0.01; BA: −0.56, 95% CI: −1.01, −0.09; all, −0.50, 95% CI: −0.82, −0.18). The MI and BA groups demonstrated differing patterns of change in affect. The MI group demonstrated significant increases only in the happy (positive affect) sub-scale while the BA group only demonstrated declines in the depressed affect and somatic subscales. The frequency of moodiness declined significantly in the BA group, but not the MI group. Automatic negative thoughts, perceived intelligence, problem solving, and general self-efficacy showed no significant change in either group. There were no significant between group differences at follow-up.

Table 3:

Pre/post Changes in Protective and Vulnerability Factors for Entire Sample

| Number Responding | Pre Mean/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Post Mean/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Pre vs. Post P-value | Group Comparison P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | |||||||

| Importance of preventing depression | 63 | 7.64 | 2.64 | 8.41 | 1.78 | 0.01 | 0.68 |

| Self-efficacy in preventing depression | 63 | 7.51 | 2.26 | 8.03 | 1.63 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Readiness to prevent depression | 61 | 7.41 | 2.09 | 7.79 | 1.81 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Stage of change | 68 | 2.70 | 1.35 | 3.28 | 1.50 | <0.004 | 0.24 |

| Symptoms of other Mental Disorders and General Health | |||||||

| Generalized anxiety symptoms | 63 | (48.05) | (37) | (43.08) | (28) | 0.65 | 0.24 |

| Panic disorder symptoms | 43 | (25.32) | (20) | (20.31) | (13) | 0.37 | 0.16 |

| Problem drinking (> 5 drinks) | 75 | (11.84) | (9) | (6.25) | (4) | 0.26 | 0.95 |

| Problem drinking (more alcohol h t an usual) | 30 | (6.33) | (5) | (4.69) | (3) | 0.48 | 0.64 |

| Affect Regulation | |||||||

| Moodiness frequency in last 12 months | 43 | 2.96 | 093 | 2.43 | 0.70 | <0.004 | 0.31 |

| CES-D depressed affect sub scale (alpha=0.830 | 64 | 5.21 | 3.70 | 4.09 | 3.87 | <0.0002 | 0.24 |

| CES-D Happy (positive affect subscale) (alpha=0.79) | 64 | 7.01 | 3.08 | 7.93 | 2.79 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| CES-D Somatic and retardation subscale (alpha=0.67) | 64 | 6.91 | 3.56 | 58.3 | 3.98 | 0.01 | 0.82 |

| CES- D Interpersonal Subscale (alpha=0.69) | 64 | 1.73 | 1.68 | 15.9 | 1.92 | <0.002 | 0.47 |

| CES-D 20 (alpha= 0.91) | 77 | 22.28 | 11.43 | 16.83 | 10.20 | <0.001 | 0.97 |

| Cognition and Self- efficacy | |||||||

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised Score (alpha= 0.95) | 63 | 60.18 | 24.27 | 59.23 | 22.90 | 0.74 | 0.52 |

| Generalize Self-efficacy scale (alpha= 0.73) | 29 | 6.32 | 3.53 | 7.07 | 3.33 | 0.26 | 0.33 |

| Self-rate d health | 62 | 2.57 | 1.09 | 2.79 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 0.59 |

| Self-rated intelligence | 47 | 4.29 | 1.19 | 4.07 | 1.10 | 0.15 | 0.66 |

| Problem solving | 43 | 2.32 | 0.97 | 2.51 | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| Self - efficacy in affect regulation | 31 | 3.22 | 0.95 | 3.42 | 0.98 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

| Family | |||||||

| Perceived Social Support Family Scale (alpha= 0.90) | 47 | 5.48 | 5.80 | 5.00 | 5.08 | 0.28 | 0.49 |

| Want to leave home | 43 | 3.06 | 1.22 | 2.65 | 1.27 | 0.02 | 0.74 |

| Closeness to residential mother | 42 | 3.95 | 0.99 | 3.67 | 1.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Closeness to residential father | 40 | 2.93 | 1.47 | 3.08 | 1.33 | 0.58 | 0.42 |

| Peer | |||||||

| Perceived Social Support Peers (alpha= 0.82) | 46 | 7.76 | 4.84 | 12.50 | 3.82 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Social acceptance | 46 | 2.29 | 1.08 | 2.37 | 1.07 | 0.11 | 0.90 |

| Closeness to people at school | 45 | 2.57 | 0.98 | 2.42 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.31 |

| School | |||||||

| Perceived Academic Impairment (school scale) | 34 | 11.07 | 0.78 | 3.60 | 9.19 | 3.45 | 0.42 |

| Most recent English grade | 34 | 2.17 | 1.00 | 2.04 | 1.04 | 0.23 | 0.41 |

| Most recent math grade | 33 | 2.38 | 1.10 | 2.24 | 1.09 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

Table 4:

Pre/post Changes in Protective and Vulnerability Factors for the Motivational Interview Group primary care/Internet studies. They believed that the major study endpoints had been reached (significant pre/post changes in measures of depressed mood in both groups).

| Number Responding | Pre Mean/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Post Mea n/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Pre vs. Post P -value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | ||||||

| Importance of preventing depression | 23 | 7.63 | 2.61 | 8.50 | 1.73 | 0.01 |

| Self-efficacy in preventing depression | 33 | 7.68 | 2.14 | 8.32 | 1.61 | 0.05 |

| Readiness to prevent depression | 33 | 7.28 | 2.05 | 8.12 | 1.84 | 0.04 |

| Stage of change | 33 | 2.85 | 1.31 | 3.49 | 1.38 | 0.01 |

| Symptoms of other Mental Disorders and General Health | ||||||

| Generalized anxiety symptoms | 24 | (40) | (16) | (50) | (17) | 0.16 |

| Panic disorder symptoms | 39 | (21.95) | (9) | (27.27) | (9) | 0.56 |

| Problem drinking (> 5 drinks) | 14 | (10.26) | (4) | (6.06) | (2) | 0.56 |

| Problem drinking (more alcohol than usual) | 23 | (2.44) | (1) | (5.88) | (2) | 0.56 |

| Affect Regulation | ||||||

| Moodiness frequency in last 12 months | 33 | 2.88 | 0.90 | 2.33 | 0.76 | 0.11 |

| CES-D depressed affect subscale (alpha =0.830 | 32 | 4.88 | 3.54 | 4.44 | 3.62 | 0.10 |

| CES-D Happy (positive affect subscale) (alpha=0.79) | 32 | 7.34 | 3.12 | 8.38 | 2.54 | <0.001 |

| CES-D Somatic and retardation subscale (alpha=0.67) | 32 | 6.73 | 3.24 | 6.00 | 4.26 | 0.64 |

| CES-D Interpersonal Subscale (alpha=0.69) | 32 | 1.78 | 1.72 | 1.69 | 1.91 | 0.01 |

| CES-D 20 (alpha= 0.91) | 39 | 21.24 | 10.80 | 16.74 | 9.62 | 0.01 |

| Cognition and Self -efficacy | ||||||

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised Score (alpha= 0.95) | 32 | 59.96 | 22.77 | 60.06 | 22.46 | 0.98 |

| Generalize Self-efficacy scale (alpha= 0.73) | 21 | 6.49 | 3.49 | 7.47 | 3.45 | 0.37 |

| Self-rated health | 34 | 2.88 | 1.05 | 2.87 | 1.14 | 0.33 |

| Self-rated intelligence | 24 | 4.28 | 1.32 | 4.00 | 1.04 | 0.36 |

| Problem solving | 15 | 2.27 | 0.95 | 2.43 | 1.08 | 0.39 |

| Self-efficacy in affect regulation | 14 | 3.33 | 0.66 | 3.38 | 0.99 | 0.85 |

| Family | ||||||

| Perceived Social Support Family Scale (alpha= 0.90) | 22 | 6.21 | 5.76 | 5.86 | 5.44 | 0.59 |

| Want to leave home | 23 | 3.22 | 1.27 | 2.71 | 1.16 | 0.06 |

| Closeness to residential mother | 22 | 3.85 | 1.04 | 3.96 | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| Closeness to residential father | 21 | 3.30 | 1.17 | 3.24 | 1.37 | 0.41 |

| Peer | ||||||

| Perceived Social Support Peers (alpha= 0.82) | 25 | 8.55 | 4.95 | 12.08 | 4.30 | <0.001 |

| Social acceptance | 25 | 2.27 | 1.03 | 2.39 | 1.12 | 0.07 |

| Closeness to people at school | 29 | 2.75 | 0.93 | 2.29 | 0.95 | 0.50 |

| School | ||||||

| Perceived Academic Impairment (school scale) | 29 | 11.31 | 3.34 | 8.78 | 3.16 | 0.06 |

| Most recent English grade | 28 | 2.28 | 1.03 | 2.17 | 1.17 | 0.26 |

| Most recent math grade | 33 | 2.32 | 1.16 | 2.08 | 1.08 | 0.06 |

Table 5:

Pre/post Changes in Protective and Vulnerability Factors for the Brief Advice Group

| Number Responding | Mean/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Mean/(Percentage) | SD/(number) | Post P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | ||||||

| Importance of preventing depression | 29 | 7.65 | 2.72 | 8.31 | 1.87 | 0.26 |

| Self- efficacy in preventing depression | 30 | 7.31 | 2.41 | 7.69 | 1.61 | 0.56 |

| Readiness to prevent depression | 29 | 7.57 | 2.15 | 7.41 | 1.72 | 0.71 |

| Stage of change | 19 | 2.54 | 1.39 | 3.06 | 1.61 | 0.15 |

| Symptoms of other Mental Disorders and General Health | ||||||

| Generalized anxiety symptoms | 20 | (56.76) | (21) | (35.48) | (11) | 0.08 |

| Panic disorder symptoms | 31 | (28.95) | (11) | (12.9) | (4) | 0.03 |

| Problem drinking (> 5 drinks) | 29 | (13.51) | (5) | (6.45) | (2) | 0.33 |

| Problem drinking (more alcohol than usual) | 25 | (10.53) | (4) | (3.33) | (1) | 0.18 |

| Affect Regulation | ||||||

| Moodiness frequency in last 12 months | 19 | 3.06 | 0.97 | 2.55 | 0.60 | 0.01 |

| CES-D depressed affect subscale (alpha=0.830 | 32 | 5.55 | 3.88 | 3.74 | 4.13 | 0.01 |

| CES-D Happy (positive affect subscale) (alpha=0.79) | 32 | 6.67 | 3.05 | 7.48 | 0.75 | 0.20 |

| CES-D Somatic and retardation subscale (alpha=0.67) | 32 | 7.09 | 3.90 | 5.66 | 3.75 | 0.049 |

| CES-D Interpersonal Subscale (alpha=0.69) | 32 | 1.69 | 5.02 | 1.50 | 1.95 | 0.04 |

| CES-D 20 (alpha= 0.91) | 16 | 23.34 | 12.09 | 16.92 | 10.89 | <0.001 |

| Cognition and Self-efficacy | ||||||

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised Score (alpha= 0.95) | 31 | 60.41 | 26.11 | 58.37 | 23.70 | 0.65 |

| Generalize Self-efficacy scale (alpha= 0.73) | 18 | 6.12 | 3.61 | 6.63 | 3.20 | 0.50 |

| Self-rated health | 16 | 2.22 | 1.05 | 2.70 | 0.86 | 0.09 |

| Self-rated intelligence | 25 | 4.30 | 1.11 | 4.15 | 1.18 | 0.29 |

| Problem solving | 20 | 2.38 | 1.01 | 2.60 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| Self-efficacy in affect regulation | 19 | 3.11 | 1.19 | 3.45 | 0.99 | 0.08 |

| Family | ||||||

| Perceived Social Support Family Scale (alpha= 0.90) | 25 | 4.83 | 5.88 | 4.24 | 4.72 | 0.35 |

| Want to leave home | 21 | 2.89 | 1.15 | 2.58 | 1.43 | 0.19 |

| Closeness to residential mother | 20 | 4.04 | 0.95 | 3.35 | 1.18 | 0.01 |

| Closeness to residential father | 23 | 2.61 | 1.64 | 2.89 | 1.29 | 1.00 |

| Peer | ||||||

| Perceived Social Support Peers (alpha= 0.82) | 21 | 7.10 | 4.75 | 12.85 | 3.40 | <0.001 |

| Social acceptance | 20 | 2.32 | 1.16 | 2.35 | 1.04 | 0.62 |

| Closeness to people at school | 19 | 2.36 | 1.02 | 2.58 | 0.84 | 0.11 |

| School | ||||||

| Perceived Academic Impairment (school scale) | 18 | 10.79 | 3.91 | 9.65 | 3.77 | 0.07 |

| Most recent English grade | 20 | 2.06 | 0.97 | 1.91 | 0.90 | 0.58 |

| Most recent math grade | 21 | 2.44 | 1.05 | 2.42 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

Figure 3:

Depressed Mood Baseline and Follow-up

Family

There was no change in the family social support scale in either group. There was a reduction in desire to leave home in the entire cohort and this approached significance in the MI group, but not the BA group (Tables 3, 4 and 5). Conversely, there was an increase in closeness to mother in the BA group (borderline significance for the entire cohort), but no change noted in closeness to father in either group.

Peer and School

Adolescents in both groups demonstrated significant improvements in social support from peers with moderate to large effect sizes (MI: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.18, 1.32; BA: 1.39, 95% CI: 0.75, 1.99; all: 1.09, 95% CI: 0.64, 1.52) (Figure 4). There was a statistically borderline trend toward lower acceptance (higher score) by peers in the MI group. Perceived impairment of school performance declined significantly in the entire cohort and borderline significance in both groups with moderate effect sizes (MI: −0.77, 95% CI: −1.37 0.14; BA: −0.30, 95% CI: −0.95, 0.36; all: −.052, 95% CI: −0.97, −0.07). For the MI group there was a borderline trend toward higher most recent math grade. There were no significant between group differences at follow-up.

Figure 4:

Friends Social Support Baseline and Follow-up

Adverse Event

There was one suicide attempt (one week after enrollment) in the BA arm who never visited the Internet site and who had a prior history of self-harm behavior. The Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) elected to stop enrollment at 84 (N of intended=96) because it believed that individuals with past psychiatric hospitalizations or attempts should not be enrolled in future primary care/Internet studies. They believed that the major study endpoints had been reached (significant pre/post changes in measures of depressed mood in both groups).

Evaluation of Effect of Missing Data

We found no relationship between being a responder and non-responder and demographic or depression related variables (baseline or follow-up). When missing values were imputed using last observation carried forward, there was no change in statistical significance for the main results.

Discussion

Both versions of this primary care Internet-based intervention for adolescent depression demonstrated favorable pre/post changes in individual, and peer/school factors. There was a significant increase in motivation to prevent depressive disorder in the entire cohort and in the MI group supporting hypothesis one. Depressed mood and frequency of moodiness declined significantly in both groups (borderline for moodiness in MI), contrasting with expectations in hypothesis two. There were no changes in automatic negative thoughts or general self-efficacy. In terms of family relationships, there was a decrease in desire to leave home in the MI group while closeness to mother increased in the BA group (trend for whole cohort). In terms of peers and school, there was an increase in peer social support and decrease in perceived school impairment in both groups which did not support hypothesis three that only the MI group would demonstrate improvement.

Depressed mood declined in both groups while panic disorders decreased in the BA group and motivation increased in the MI group, but without changes in established vulnerability factors such as automatic negative thoughts or general self-efficacy. The improvement in motivation is consistent with a “doctor” effect (Moreau, Boussageon, Girier, & Figon, 2006) and consistent with prior work in substance abuse in adolescence (Erol & Erdogan, 2008; Feldstein & Forcehimes, 2007; Skaret, Weinstein, Kvale, & Raadal, 2003) but is new for depressive disorder. These declines in depressed mood are consistent with findings with studies of self-directed interventions in adults in primary care (Christensen, Griffiths, & Jorm, 2004; Willemse, Smit, Cuijpers, & Tiemens, 2004), and face-to-face interventions for adolescents (Jaycox, Reivich, Gillham, & Seligman, 1994; Spence, 2003; Stein, Zitner, & Jensen, 2006). The lack of change in automatic negative thoughts or general self-efficacy is consistent with results from a school-based program (Possel, Horn, Groen, & Hautzinger, 2004). Declines in panic disorder and depressed mood CES-D subscales in the BA group while the MI group demonstrated only increases in positive affect may suggest alternate pathways to improvement unrelated to measures such as automatic negative thoughts or self-efficacy. Perhaps the BA group employed a behavioral activation approach to reduce negative emotions while the MI group was encouraged by the interviewer to focus on goal-oriented behavior that produced more frequent rewards and generated positive affect (Jacobson, 2001). This is supported by the borderline increase in affect regulation self-efficacy in the BA group but not the MI group and conversely the enhancement in motivation in the MI but not the BA group.

Improvements in peer social support, lowering of desire to leave home, and declines in school impairment have not been reported in prior studies of depression prevention in primary care settings. Results for social and problem solving skills for preventive interventions in schools have been inconsistent with regard to pre/post changes (Possel et al., 2004; Spence, 2003). At least one other study of adolescents failed to demonstrate changes in coping skills (Horowitz, Garber, Ciesla, Young, & Mufson, 2007). While family social support did not change, the finding that adolescents had less desire to leave home is consistent with the finding that parent and child family training can reduce internalizing symptoms and increase relationship satisfaction in adolescents (Beardslee et al., 2003). Again, the finding that closeness to mother increased only in the BA group and desire to leave only significantly decreased in the MI group suggests alternate pathways to protection and reduction in depressed mood in the two conditions.

The greatest strength of this study is the evaluation of an intervention preventing depressive disorder that can easily be disseminated to diverse practice settings, with adolescent participants representing the range of geography, ethnicity, and education in the US. The intervention was implemented with high fidelity by physicians and the great majority of adolescents engaged in the Internet program. The greatest limitation of this study is the fact that many post study observations of vulnerability factors are missing. While some of the missing data can be explained by clerical error and challenges of implementing a complex study with voluntary cooperation of community clinics, the possibility of systematic bias must be considered. While there was no variation by socio-demographic factors or depressed mood, there may be systematic bias favoring those who had improved responding, thus biasing results toward pre/post effects in the risk factors other than depressed mood. In this case, there was no evidence of systematic bias of this type (no variation of degree of CES-D change). Similarly, using the most conservative method of imputation (last observation carried forward), the observed main results did not change. Also, as this is a preventive intervention and primarily intended to compare differences within groups over time, we saw limited if any differences between groups at follow-up.

Conclusions

There is substantial evidence based on pre/post changes in mood, changes in vulnerability factors, and ratings and from adolescents and parents that participants benefited from participation from the depression prevention model. Depression prevention investigators should consider alternative, bottom-up community models which harness natural care systems and the adolescents’ capacity for independent change and “self-organization” (Holden, 2005) which contrasts the highly structured curricular models which have prevailed in the field. Models such as this, based on Complex Adaptive Systems theory, have been proposed for functional disorders (e.g. fibromyalgia) in primary care (Martinez-Lavin, Infante, & Lerma, 2008) and for structures to support child mental health (Earls, 2001). Primary care physicians’ options for the mild to moderately depressed adolescent are currently constrained by concerns related to black box warnings for medications and limited availability of psychotherapy referrals. The results from this study suggest that preventive intervention with self-directed learning and motivational engagement in primary care may be an important future model. Clinicians should consider engaging mildly-moderately depressed youth at risk for progressing to major depression with self-help books or Internet-based programs along with close follow-up. Policy makers should consider developing new reimbursement approaches to cover “hybrid” services that include Internet and primary services, as well as new public health approaches to prevention involving Internet-based learning. Such approaches can allow the primary care physician to better impact the mental health of adolescents. The complete intervention is available for free public access and use at the website of http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu.

Acknowledgements/Conflict of Interest

Supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Value Grant and a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH K-08 MH 072918-01A2). Benjamin W. Van Voorhees has served as a consultant to Prevail Health Solutions, Inc and the University of Hong Kong to develop Internet-based interventions.

References

- Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Anderson M. Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;11(3):477–497. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron G, Ravaud P, Samson A, Giraudeau B. Missing data in randomized controlled trials of rheumatoid arthritis with radiographic outcomes: a simulation study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2008;59(1):25–31. doi: 10.1002/art.23253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):e119–131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs LJ, Briggs RM, Gagne LJ, Wager WW. Principles of Instructional Design. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CC. Cultivating resiliency in youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(5):375–381. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7434):265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37945.566632.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN. The coping with stress course adolescent: workbook. Portland, OR: Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN. Adolescent use of web-based depression treatment programs. Portland, OR: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Earls F. Community factors supporting child mental health. Child Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;10(4):693–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol S, Erdogan S. Application of a stage based motivational interviewing approach to adolescent smoking cessation: The Transtheoretical Model-based study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Forcehimes AA. Motivational interviewing with underage college drinkers: a preliminary look at the role of empathy and alliance. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(5):737–746. doi: 10.1080/00952990701522690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grembowski DE, Martin D, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Katon W, Williams B, et al. Managed care, access to mental health specialists, and outcomes among primary care patients with depressive symptoms. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(4):258–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2006;8(1):102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden LM. Complex adaptive systems: concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(6):651–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Garber J, Ciesla JA, Young JF, Mufson L. Prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: a randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal prevention programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(5):693–706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NSMC, Dimdjian S. Behavioral activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(3):255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Reivich KJ, Gillham J, Seligman ME. Prevention of depressive symptoms in school children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;32(8):801–816. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Howard BL, Hays RC. Self-referent speech and psychopathology: The balance of positive and negative thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1989;13:583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression & Anxiety. 1998;7(1):3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara SA, Van Voorhees BW, Gollan JK, Alexander GC. A qualitative exploration of depression in emerging adulthood: Disorder, development, and social context. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(4):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(7):807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lavin M, Infante O, Lerma C. Hypothesis: the chaos and complexity theory may help our understanding of fibromyalgia and similar maladies. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;37(4):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau A, Boussageon R, Girier P, Figon S. [The “doctor” effect in primary care] Presse Med. 2006;35(6 Pt 1):967–973. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(06)74729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson LDK, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. New York, New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nation M, Crusto C, Wandersman A, Kumpfer KL, Seybolt D, Morrissey-Kane E, et al. What works in prevention. Principles of effective prevention programs American Psychologist. 2003;58(6–7):449–456. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LIM, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possel P, Horn AB, Groen G, Hautzinger M. School-based prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: a 6-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):1003–1010. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000126975.56955.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke MS, Simmons A. Vulnerability to depression among adolescents: Implications for cognitive treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, Katzenellenbogen R. Childhood and adolescent depression: the role of primary care providers in diagnosis and treatment. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2005;35(1):6–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santor DA, Poulin C, LeBlanc JC, Kusumakar V. Online health promotion, early identification of difficulties, and help seeking in young people. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(1):50–59. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242247.45915.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaret E, Weinstein P, Kvale G, Raadal M. An intervention program to reduce dental avoidance behaviour among adolescents: A pilot study. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2003;4(4):191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence S, Sheffield JK, Donovan CL. Preventing adolescent depression: An evaluation of the problem solving for life program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):3–13. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RE, Zitner LE, Jensen PS. Interventions for adolescent depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):669–682. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart SRM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy A Clinicians Guide. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T. Geographic disparities in children’s mental health care. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):e308. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.e308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Ellis JM, Gollan JK, Bell CC, Stuart SS, Fogel J, et al. Development and process evaluation of a primary care Internet-based intervention to prevent depression in emerging adults. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;9(5):346–355. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Ellis JM, Stuart S, Fogel J, Ford DE. Pilot study of a primary care depression prevention intervention for late adolescents. Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review. 2005;14(2):40–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Paunesku D, Kuwabara SA, Basu A, Gollan J, Hankin BL, et al. Protective and vulnerability factors predicting new-onset depressive episode in a representative of U.S. adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(6):605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Wang NY, Ford DE. Managed care organizational complexity and access to high-quality mental health services: perspective of U.S. primary care physicians. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;25(3):149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse GR, Smit F, Cuijpers P, Tiemens BG. Minimal-contact psychotherapy for sub-threshold depression in primary care. Randomised trial British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;185:416–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerbrot RA, Maxon L, Pagar D, Davies M, Fisher PW, Shaffer D. Adolescent depression screening in primary care: feasibility and acceptability. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):101–108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]