Abstract

Acute hypoglycemia is associated with neuronal injury in the mature human and rodent brains. Even though hypoglycemia is a common metabolic problem during development, its effects on the developing brain are not well understood. To characterize the severity of regional brain injury, postnatal day (P) 7, P14, P28 (N=20–30/age) and adult rats (N=8–12) were subjected to acute hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration (mean blood glucose concentration: 30.0±0.1 mg/dL for 210 min). Neuronal injury in the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus and hypothalamus was assessed 24 hr, 72 hr and 1 wk later by determining the number of degenerating cells positive for Fluoro-Jade B (FJB+) in the region. Compared with age-matched control, greater number of FJB+ cells was present per brain section of P14, P28 and adult hypoglycemia groups (P<0.005, each). The cerebral cortex was more vulnerable than hippocampus and striatum at all three ages (P<0.01). Compared with P28 (131±21) and adult (171±21) rats, fewer FJB+ cells (39±6) per brain section were present in P14 hypoglycemic rats (P<0.01, each). Hypoglycemia was not associated with cell injury in P7 rats. FJB+ cells were absent in the hypothalamus in all four ages. Similar results were present 24 hr post-hypoglycemia, where as analysis at 1 wk demonstrated efficient clearing of FJB+ cells in the brain regions of developing rats. Varying the duration of fasting did not alter the severity of regional cell injury. These results suggest that postnatal age influences the regional vulnerability to hypoglycemia-induced neuronal death in the rat brain.

Keywords: Brain, Glucose, Hypoglycemia, Neuronal injury, Newborn, Rat

1. Introduction

Hypoglycemia is a common metabolic condition in human infants and children. Newborn infants who are preterm, small- or large-for-gestation, and those with hyperinsulinemia are particularly at risk for hypoglycemia [18]. Beyond the newborn period, hypoglycemia is commonly associated with intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus [6,13]

Acute hypoglycemia is associated with neuronal injury in the mature human and rodent brains [3,26,32,35]. Extensive neuronal injury in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and striatum is seen in adult rats after profound hypoglycemia (blood glucose concentration, typically <20 mg/dL for <30 min) [3,32]. Neuronal injury has also been demonstrated in the cerebral cortex of adult rats subjected to 75 min of hypoglycemia of moderate severity (blood glucose concentration, 30–35 mg/dL) [35]. There are relatively few studies on the effects of acute hypoglycemia in developing rodents. Degenerating neurons have been demonstrated in the cerebral cortex of developing rats subjected to acute hypoglycemia on postnatal day (P) 25 [42]. Apoptotic cell injury in the hippocampus and striatum has been demonstrated in developing mice subjected to acute hypoglycemia of 4 hr duration [14].

There are no studies comparing the severity of regional neuronal injury in developing and mature rats subjected to acute hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration. Compared with the mature brain, the developing brain has limited energy reserves and accounts for a greater fraction of total body glucose consumption and therefore, may be at increased risk of injury during hypoglycemia [19]. Conversely, the developing brain has lower energy requirements than the mature brain and is capable of efficiently using non-glucose substrates, such as ketone bodies, amino acids and lactate for its energy needs [22,37]. These characteristics of the developing brain may provide neuroprotection during acute hypoglycemia.

The objective of the present study was to compare the severity of neuronal injury in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and striatum using Fluoro-Jade B (FJB) histochemistry in P7, P14, P28 and adult rats subjected to acute hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration. We hypothesized that the postnatal age alters the susceptibility to neuronal injury during acute hypoglycemia. FJB is a putative marker of degenerating neurons [28] and has been used to determine post-hypoglycemic cell injury in developing and mature rodent brains [32,35,41,42,44]. Rats of these ages were chosen due to the neurodevelopmental similarities with the pediatric populations at risk for hypoglycemia, namely, the preterm infant (P7), full term infant (P14) and young child (P28) [12]. The brain regions were chosen due to their vulnerability in previous studies of acute hypoglycemia in developing and mature rodents [3,14,42]. Due to its central role in brain glucose sensing and energy homeostasis [16], neuronal injury in hypothalamus was also assessed.

2. Results

2.1 Blood glucose and β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations

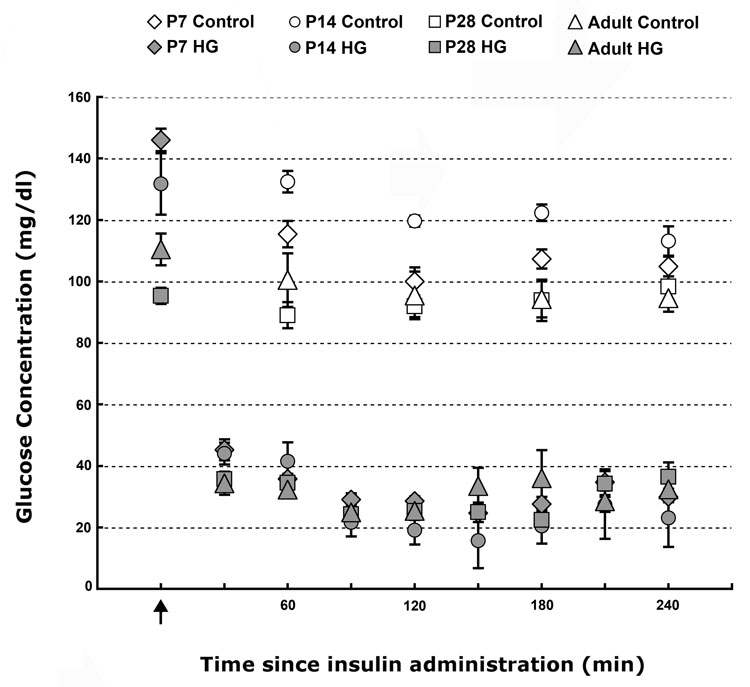

We produced hypoglycemia in P7, P14, P28 and adult rats using a combination of fasting and insulin administration [40]. Beginning 30 min after the administration of insulin, the mean blood glucose concentrations were lower in all four hypoglycemia groups when compared with the age-matched control groups (P<0.01, Fig. 1). Comparable blood glucose concentrations were maintained between 30 and 240 min (i.e. for 210 min) in the four hypoglycemia groups (Fig. 1). Euglycemia (blood glucose >50 mg/dl) was achieved within 30 min of termination of hypoglycemia in all rats (data not shown).

Figure 1. Blood glucose concentrations in control and hypoglycemia groups in postnatal day 7, 14, 28 and adult rats.

Values are mean±SEM glucose concentrations from 6–15 rats/age.group−1 at each time point. Arrow indicates the time of insulin administration. Compared with age-matched control group, blood glucose concentrations were lower in the four hypoglycemia groups (P<0.01, each). The mean blood glucose concentrations were similar among the four hypoglycemia groups. (Abbreviations: HG, hypoglycemia group; P, postnatal day).

The blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentration at 0 min (i.e. prior to the induction of hypoglycemia) was higher in P28 rats (2.01 ± 0.11 mmol/L) than in the other three ages [(mmol/L) 0.78 ± 0.04 (P7), 1.43 ± 0.42 (P14) and 1.07 ± 0.12 (adult), P<0.01, each]. Blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentration was higher in the P7 hypoglycemia group at 240 min (i.e. prior to the termination of hypoglycemia), when compared with the adult hypoglycemia group (1.33 ± 0.24 mmol/L vs. 0.55 ± 0.15 mmol/L, P=0.02). Trend for a similar effect was present between P7 and P14 (0.65 ± 0.06 mmol/L, P=0.06), and between P7 and P28 (0.73 ± 0.07 mmol/L, P=0.09) hypoglycemia groups.

None of the rats in the four control groups died. The mortality rate was similar among the four hypoglycemia groups [7% (P7), 8% (P14), 6% (P28) and 9% (adult)]. All deaths occurred between 60 and 210 min after the administration of insulin and there was no delayed mortality. The blood glucose concentration of animals that died was 23.2±1.2 mg/dL, and was <20 mg/dL at the time of death in all rats.

2.2 FJB Histochemistry

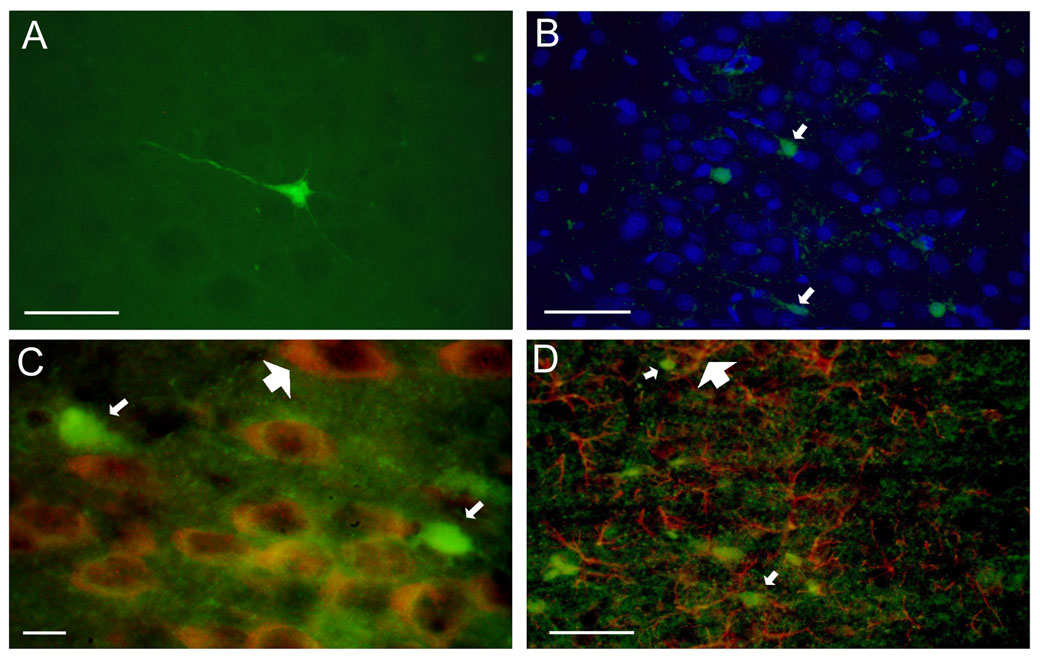

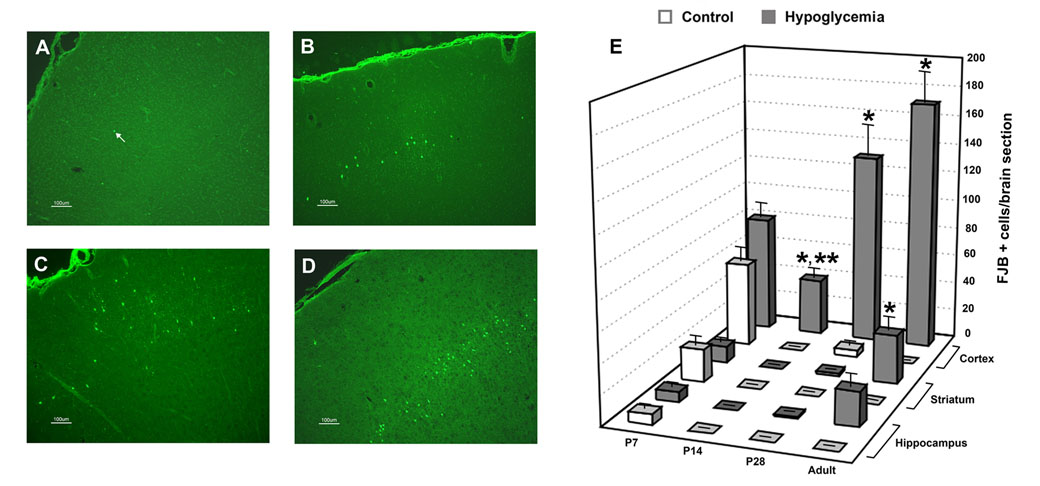

Neuronal injury was assessed 24 hr, 72 hr and 1 wk after hypoglycemia using FJB histochemistry as in previous studies [32,35,41,42,44]. There were rare (0–3) FJB+ cells in brain sections of the control groups, except at P7, where round-shaped FJB+ cells were present in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and striatum. FJB+ cells were present in all examined brain sections in the hypoglycemia group in all four age groups, They were generally isolated and had characteristics of neurons with staining of the cell body and neuronal processes at 24-hr and 72-hr analyses (Fig. 2A). FJB+ cells appeared shrunken with short processes at 1 wk analysis (not shown). FJB+ cells co-localized with 4’6’-diamidino-2-phenyllindole (DAPI; Fig. 2B) but not with antibody for neuronal nuclei (NeuN; Fig. 2C) or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Fig. 2D) at all three times of analyses. FJB+ cells were typically present in relatively deep cortical layers (III–VI) without obvious laminar distribution (Fig 3 A–D). Asymmetry between the hemispheres was often present, especially in the adult group.

Figure 2. Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in the cerebral cortex 72 hr after acute hypoglycemia.

(A) A single FJB positive cell demonstrates features of neuron with staining of the cell body and processes. (B) FJB positive cells (green, small arrows) co-localized with DAPI (blue), but not with (C) NeuN (red, large arrow) or (D) GFAP (red, large arrow). (20 µm coronal brain sections from postnatal day 28 hypoglycemic rats; bar = 50 µm in A, B and D, and bar = 10 µm in C. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4’6’-diamidino-2-phenyllindole; FJB, fluoro-jade B; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; NeuN, neuronal nuclei).

Figure 3. Degenerating cells positive for fluoro-jade B 72 hr after acute hypoglycemia.

Fluoro-Jade B positive (FJB+) cells in the cerebral cortex of (A) postnatal day (P) 7, (B) P14, (C) P28 and (D) adult rats 72 hr after acute hypoglycemia. Arrow in panel A point to a FJB+ cell. (E) FJB+ cells in the cerebral cortex, striatum and hippocampus of control and hypoglycemia groups in P7, P14, P28 and adult rats 72 hr post-hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration. Values are mean±SEM number of FJB+ cells per brain section in the region. N= 4–6 brain sections from 6–8 rats/group.age−1. *P<0.005 vs. corresponding brain region of age-matched control group; **P<0.005 vs. cerebral cortex of P28 and adult hypoglycemia groups, each. There was no difference between control and hypoglycemia groups for any of the regions in P7 rats.

2.3 FJB analysis 72 hr post-hypoglycemia

When compared with the age-matched control group, greater number of FJB+ cells per brain section were present in the P14, P28 and adult hypoglycemia groups (P<0.005, each, Fig 3E). Comparable number of FJB+ cells was present in the corresponding brain regions of the control and hypoglycemia groups in P7 rats (Fig. 3E). The cerebral cortex was the most commonly affected brain region in P14, P28 and adult age groups (P<0.01, each, Fig 3E). FJB+ cells were present in the striatum and hippocampus only in the adult hypoglycemia group among the three ages (Fig. 2E). Compared with the P28 and adult hypoglycemia groups, there were fewer FJB+ cells in the cerebral cortex of the P14 hypoglycemia group (P≤0.005, each, Fig. 3E). Moreover, there were age-related variations in the regional distribution of neuronal injury: The parietal and piriform cortices in the adult brain, the cingulate, orbital and temporal cortices at P28, and the orbital cortex at P14 were the cortical regions with most FJB+ cells (P<0.01). FJB+ cells were not present in the hypothalamus in any age group.

2.4 FJB analysis 24 hr and 1 wk post-hypoglycemia

A previous study demonstrated that the time of tissue harvest does not affect the assessment of post-hypoglycemic neuronal injury in adult rats [35]. As a similar effect has yet to be determined in developing rats, neuronal injury was assessed 24 hr and 1 wk post-hypoglycemia in P7, P14 and P28 rats, in addition to the 72 hr analysis. Analysis at 24 hr demonstrated a similar regional distribution (cortex>striatum=hippocampus, P<0.01, each) and influence of age (P14<P28, P=0.03) as the 72 hr analysis (Table 1). Likewise, there were no differences in the number of FJB+ cells in the brain regions of P7 control and hypoglycemia groups at 24 hr analysis. Compared with 24 hr and 72 hr analyses, fewer FJB+ cells were present at 1 wk analysis in the hypoglycemia group in all three developmental ages, as well as in the P7 control group (P<0.01, Table 1).

Table 1.

FJB Positive Cells in the Cerebral Cortex, Striatum and Hippocampus of Control and Hypoglycemia Groups

| Age (days) | Control Group | Hypoglycemia Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral cortex | Striatum | Hippocampus | Cerebral cortex | Striatum | Hippocampus | |

| 24 hour analysis | ||||||

| 7 | 77±7 | 41±8 | 13±2 | 104±17 | 21±4 | 14±3 |

| 14 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 61±10a,b | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| 28 | 3±1 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 117±18a | 3±3 | 1±0 |

| 1 wk analysis | ||||||

| 7 | 7±3 | 0±0 | 3±1 | 11±4c | 1±0 | 2±1 |

| 14 | 4±3 | 0±0 | 3±1 | 16±10c | 2±1 | 4±2 |

| 28 | 3±1 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 28±11c | 0±0 | 1±0 |

Values are mean±SEM number of FJB+ cells in the region from 4–6 brain sections, each from 3–6 rats/age in the control group and 5–6 rats/age in the hypoglycemia group at each time of analysis.

P<0.005 vs. cerebral cortex of control group at 24 hr analysis

P=0.03 vs. cerebral cortex of P28 hypoglycemia group at 24 hr analysis

P<0.01 vs. cerebral cortex of hypoglycemia group of corresponding age at 24 hr analysis

2.5 Effect of duration of fasting on FJB analysis 72 hr post-hypoglycemia

In order to produce hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration, it was necessary to subject P7, P14 and P28 rats to different durations of fasting prior to the administration of insulin [40]. In the experiments to determine whether the duration of fasting had an impact on neuronal injury, separate groups of P7 and P14 rats were subjected to overnight fasting, and P28 rats were not fasted before being injected with insulin. The mean blood glucose concentrations in P7 (30±1 mg/dL) and P14 (24±3 mg/dL) rats fasted overnight were comparable to corresponding values in age-matched rats fasted for shorter durations (P7: 32±1 mg/dL and P14: 26±2 mg/dL, Fig 1). The mean number of FJB+ cells per brain section in the cerebral cortex of rats fasted overnight (P7: 89±5 and P14: 55±14) was similar to those fasted for a shorter duration (P7: 80±9 and P14: 39±6, Fig 2E). Hypoglycemia (blood glucose <40 mg/dL) was present only between 30 min and 150 min in P28 rats injected with insulin without prior fasting (i.e. for 120 min vs. 210 min in those fasted overnight, Fig 1). Nevertheless, comparable number of FJB+ cells per brain section (107±36) was present in the cerebral cortex of these rats as in those fasted overnight (131±21, Fig 2E).

3. Discussion

Using a combination of fasting and insulin, we were able to produce hypoglycemia of comparable severity and duration in rats between the ages of P7 and adulthood. The blood glucose concentration (<35 mg/dL) achieved in the present study is associated with decreased brain glucose concentration in both developing and adult rats [22]. In spite of hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration, there were variations in the number and regional distribution of FJB+ cells among the different ages. This suggests that postnatal age influences the regional vulnerability to hypoglycemia-induced neuronal death in the rat brain.

The staining characteristics of the FJB+ cells suggest that they are neurons, which is supported by the non-co-localization with the astrocyte marker GFAP. The fact that FJB+ cells failed to co-localize with neuronal marker NeuN does not negate this postulation, given the rapid loss of NeuN immunoreactivity in degenerating neurons [5]. Previous studies in adult and developing rodents also failed to demonstrate NeuN immunoreactivity in dying neurons within hours of hypoglycemia [14,35].

The regional distribution of injury in the P28 and adult rats in the present study is comparable to previous reports of acute hypoglycemia in rats of corresponding ages [35,41]. Compared with a previous study [35], we found greater number of FJB+ cells in the cerebral cortex of adult rats. This may be a reflection of the longer duration of hypoglycemia in our study (210 min vs. 75 min in the study by Tkacs et al [35]). Prolonged hypoglycemia may also have been responsible for the neuronal injury in the hippocampus and striatum of adult hypoglycemic rats in our model. Neuronal injury in these areas was not demonstrated in the afore-mentioned study by Tkacs et al [35], but is typically found after profound hypoglycemia in adult rats [3,32]. We are not aware of previous studies of acute hypoglycemia in P7 and P14 rats. Comparable number of FJB+ cells were found in P7 control and hypoglycemia groups, suggesting that acute hypoglycemia was not associated with neuronal injury at this age. The FJB+ cells at this age likely reflect the programmed cell death that is active until P10 [27,39]. Finally, consistent with a previous study in adult rats [35], the hypothalamus was spared in all ages, likely secondary to its low glucose requirements [22].

The number and regional distribution of FJB+ cells at 24 hr analysis was similar to those at 72 hr analysis in the three developmental ages. This is consistent with a recent study of recurrent hypoglycemia in developing rats [44], and suggests that as in the mature bra neuronal injury occurs soon after acute hypoglycemia in the developing brain, similar to the mature brain [35]. Few, small FJB+ cells were found at 1 week assessment in all three developmental age groups. This likely reflects efficient clearing of the degenerating cells in the developing brain and is different from a previous study in adult rats [35].

The cerebral cortex was the most vulnerable region at all ages. However, there were age-related variations in involvement of the cortical regions. The reasons for injury in a specific region in the presence of global glucose insufficiency are not well known. The presence of persistently active neurons, higher glucose utilization rates, and loss of autoregulation in a brain region likely determines its vulnerability during acute hypoglycemia [1,22,25,33,35]. Of functional significance, the affected brain regions in P14 and P28 brains subserve attention and short- and long-term memory functions [9,10]. Thus, our results may provide histochemical correlates for the impaired attention and memory functions that are common in newborn infants and children with history of hypoglycemia [24,31].

We are not aware of studies that compared the effects of hypoglycemia of equivalent severity and duration on the brain among different ages in rats, spanning P7 through adulthood. Our results suggest that compared with the mature brain, the rat brain in early phases of development is resistant to injury during acute hypoglycemia. The data also suggest that the variation in fasting was not responsible for the age-related vulnerability in the developing brain. A number of factors may be responsible for the relative resistance of the early postnatal brain during hypoglycemia. When compared with the P28 and mature brains, the P7 and P14 brains have lower energy requirement, higher brain glycogen stores, and are capable of efficient transport and utilization of non-glucose energy substrates, such as ketone bodies [22,38]. Moreover, unlike in the adult, insulin does not suppress ketogenesis during hypoglycemia in neonatal rats [43]. Consistent with this, we found higher β-hydroxybutyrate concentration in P7 rats at 240 min. These factors, combined with a compensatory increase in cerebral blood flow and enhanced glucose extraction from the blood, may provide neuroprotection to the developing brain during hypoglycemia [21,37]. Differences in the developmental stage of the cells, the number and function of neurotransmitter receptors, molecular and biochemical pathways of energy metabolism, susceptibility to respiratory depression and glucose reperfusion injury may also be responsible for the age-related vulnerability during hypoglycemia [7,20,30,32]. Similar, age-related resistance of the early postnatal brain has been demonstrated in other models of perinatal injuries, such as hypoxia-ischemia [11,36].

The mortality rate in the present study is comparable to a previous report in developing mice subjected to acute hypoglycemia of comparable severity and duration. We did not monitor the electrical activity of the brain during hypoglycemia. However, rats were conscious and responsive to stimuli during hypoglycemia. A previous study in developing rats failed to demonstrate EEG isoelectricity or seizures during hypoglycemia of greater severity (blood glucose concentrations <20 mg/dl) than the present study [41]. Similarly, as we did not monitor blood gases and blood pressure, the potential occurrence of respiratory depression and hypotension, respectively, during hypoglycemia cannot be ruled out. However, while hypotension as a complication of severe hypoglycemia leads to enhanced energy failure, it does not exaggerate neuronal injury [2]. Our investigation was limited to FJB analysis. Other methods, such as terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining have been used to evaluate hypoglycemic brain injury in rodents [14,34]. However, unlike the FJB staining that stains only dead or dying cells, TUNEL staining may also index transient DNA damage due to hypoglycemia [17,35]. The type of neuron vulnerable during hypoglycemia (for example, interneurons or pyramidal neurons) was not determined in the present study and needs additional research. Finally, lack of demonstrable injury in a region may not portend normal function: Hippocampal dysfunction in the absence of detectable neuronal injury has been demonstrated with repetitive hypoglycemia in young rats [41]. Future studies are needed to evaluate energy metabolism and other factors related to cell death, such as expression of uncoupling protein and mitochondrial membrane potential, to uncover evidence of subtle injury in the developing brain during hypoglycemia.

As in previous studies [32,35,41,42,44], we used insulin to induce hypoglycemia in our model. Thus, there is a potential that insulin toxicity, rather than hypoglycemia was responsible for the neuronal injury. However, the contribution of insulin toxicity is likely to be minor since neuronal necrosis occurs only with prolonged exposure (≥ 48 hr) to insulin [23]. At lower doses, insulin attenuates neuronal injury through suppression of apoptosis [23]. Moreover, the transport of insulin across the blood brain barrier and its binding to insulin receptors is higher in newborn rats when compared with P21 and adult rats [8]. This would suggest that younger animals would be at greater risk of insulin-mediated neuronal injury. On the contrary, injury was absent in P7 rats, and was more severe in P28 and adult rats in our study. The absence of FJB+ cells in the hypothalamus of hypoglycemic rats also points against insulin-induced injury in our model. Hypothalamus has high concentration of insulin receptors [15], and exogenously administered insulin is transported to this region twice as fast as the whole brain [4]. Nevertheless, future studies of hyperinsulinemia without associated hypoglycemia (for example, hyperinsulinemia-euglycemia clamp) are necessary to conclusively exclude the potential role of insulin toxicity in our model.

In summary, while hypoglycemia is a common occurrence in early life, our data provides evidence that the rat brain is resistant to hypoglycemia-induced neuronal injury during the early postnatal period. The potential mechanisms underlying such neural protection are of high interest and require additional studies. Insights to these factors will be crucial for developing preventive and therapeutic strategies against hypoglycemic injury in the mature brain.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Animals

Developing and adult male and female Sprague Dawley rats were used in experiments. Pregnant rats were purchased (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC) and allowed to deliver spontaneously. Litter size was culled to 8–10 pups soon after birth. Dams and pups were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal care facility with 12 hr:12 hr light:dark cycle and allowed food and water ad libitum. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental protocols.

4.2 Induction of hypoglycemia

Developing (P7, P14 and P28, n=20–30/age) and adult (P60–P75, n=8–12) rats were subjected to a single episode of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia was induced using human regular insulin (Novo Nordisk Inc., Clayton, NC) in a dose of 6 IU/kg (P14, P28 and adulthood) or 10 IU/kg (P7) subcutaneously after a predetermined period of fasting (4 hr in P14, and overnight in P28 and adult) [40]. As in previous studies, P7 rats were not fasted prior to insulin administration [14,44]. The target blood glucose was <40 mg/dL. Littermates in the control group were similarly fasted and were subcutaneously injected with equivalent volume of 0.9% saline.

Rats were maintained at a temperature of 34.0±1.0°C after the insulin or saline injection [40] and fasting was continued for 240 min in all four age groups. The duration of observation was based on a previous study that demonstrated neuronal injury in developing mice subjected to similar duration of hypoglycemia [14]. Rats had free access to water during observation. Glucose concentration was measured in the whole blood collected from the tail every 30 min in the hypoglycemia group and every 60 min in the control group (n=6–15/group at each time point) using a blood glucose meter (Accu-Chek® Compact, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Whole blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentration was measured at 0 min and 240 min (n=6–8/age) using a blood ketone monitoring system (Precision Xtra™, Abbott Laboratories, Oxon, United Kingdom). Pilot studies demonstrated that a blood glucose concentration <20 mg/dL for >30 min was associated with seizures and mortality, especially in P28 and adult rats. Therefore, 10% dextrose was administered in a dose of 200 mg/kg, i.p. if the blood glucose was <20 mg/dL to all rats. Rats demonstrating obvious seizures were excluded from further analysis. Hypoglycemia was terminated 240 min after insulin administration by injecting 200mg/kg of 10% dextrose i.p. After confirmation of euglycemia (blood glucose >50 mg/dL) and normal activity, P7 and P14 rats were reunited with their respective dams, and P28 and adult rats were allowed to consume lab diet ad libitum.

4.3 FJB Histochemistry

The brain was harvested 72 hr after the conclusion of hypoglycemia in all age groups. Since the time of tissue harvest does not affect the assessment of post-hypoglycemic neuronal injury at adulthood [35], a single time point was chosen for tissue harvest at this age. As a similar effect has yet to be established in the developing brain, some P7, P14 and P28 control (n=3–6/age at each time of analysis) and hypoglycemic rats (n=5–6/age at each time of analysis) were killed either 24 hr or 1 wk after the hypoglycemia episode for brain harvest.

The rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) before undergoing in situ transcardial perfusion with 0.9% saline, followed by 5% neutral buffered formaldehyde and 5% sucrose in PBS. The brain was removed and post-fixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C, followed by serial overnight passages in 20% and 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for cryoprotection. It was then flash-frozen on a dry ice and acetone bath and was embedded in a tissue-freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences; Durham, NC) for sectioning.

Serial 20 µm coronal sections were obtained using a cryostat (Model CM1900; Leica Instruments GmbH; Nussloch, Germany) at −20°C to −25°C. FJB staining was performed according to the method described by Schmued and Hopkins [28]. Additional sections were used to assess double-label fluorescence immunohistochemistry with FJB using primary antibody to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) or Neuronal Nuclei (NeuN) in a concentration of 1:1000 (GFAP) or 1:400 (NeuN), and a secondary antibody tagged with a fluorophore (Alexa Fluor 555, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) in a concentration of 1:500. FJB and 4’6’-diamidino-2-phenyllindole (DAPI) double staining was performed using previously described methods [28,35,41].

Brain sections were examined through a 4× objective of a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600, Nikon Corporation; Shinagawa-ku; Tokyo, Japan) with CF160 infinity optics using appropriate filters. Pilot studies showed that FJB-positive (FJB+) cells were more numerous in rostral brain sections, corresponding to plates 50–54 of an atlas of the developing rat brain [29], and −2.5 mm to +3.8 mm relative to the bregma in adults. Digital microscopic images from 4 to 6 brain sections that demonstrated tissue integrity and bilateral symmetry from this region were collected at 10 × magnification using a compound microscope equipped with a camera (Nikon Digital Camera DXM1200, Nikon Corporation) and a software program (ACT-1, Nikon Corporation). All FJB+ cells in the entire cerebral cortex, hippocampus, striatum and hypothalamus of each brain section were counted in a masked fashion, and group means were determined.

4.4 Effect of the duration of fasting on hypoglycemic injury

To determine whether the duration of fasting has an effect on brain injury during insulin-induced hypoglycemia in developing rats, separate groups of P7 (n=6) and P14 rats (n=8) were fasted overnight, and some P28 rats (n=8) were not fasted, before being injected with 6 IU/Kg of insulin s.c. and were monitored for 240 min as described in section 4.2. Brains were harvested 72 hr post-hypoglycemia and the number and regional distribution of FJB+ cells in the brain sections were compared with the age-matched hypoglycemia groups described in section 4.3 above.

4.5 Statistical analysis

Group means were compared using ANOVA with age (P7, P14, P28 and adult), group (control and hypoglycemia) and time of analysis (24 hr, 72 hr and 1 wk) as fixed factors. Inter-group differences were determined post hoc using Bonferroni-adjusted unpaired t tests (SPSS, version 15, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data are presented as mean±SEM. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Grant Number NIH HD47276 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Viking Children’s Fund, and the Graduate School, University of Minnesota. The authors thank Michael Georgieff, M.D., for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DAPI

4’6’-diamidino-2-phenyllindole

- FJB

Fluoro-Jade B

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- NeuN

neuronal nuclei

- P

postnatal day

- TUNEL

terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the annual meetings of Pediatric Academic Societies (Ennis K, Seaquist E, Rao R. Influence of postnatal age on vulnerability to acute hypoglycemic brain injury in developing rats. E-PAS2007: 617355.3, 2007) and American Diabetes Association (Rao R, Ennis K, Tran P, Seaquist. E. Postnatal age alters the vulnerability to acute hypoglycemic brain injury in developing rats. Diabetes, 56: 100A, 2007).

Literature References

- 1.Auer RN. Hypoglycemic brain damage. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;19:169–175. doi: 10.1023/b:mebr.0000043967.78763.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auer RN, Hall P, Ingvar M, Siesjo BK. Hypotension as a complication of hypoglycemia leads to enhanced energy failure but no increase in neuronal necrosis. Stroke. 1986;17:442–449. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auer RN, Wieloch T, Olsson Y, Siesjo BK. The distribution of hypoglycemic brain damage. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1984;64:177–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00688108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks WA. The source of cerebral insulin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collombet JM, Masqueliez C, Four E, Burckhart MF, Bernabe D, Baubichon D, Lallement G. Early reduction of NeuN antigenicity induced by soman poisoning in mice can be used to predict delayed neuronal degeneration in the hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2006;398:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1902–1912. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Courten-Myers GM, Xi G, Hwang JH, Dunn RS, Mills AS, Holland SK, Wagner KR, Myers RE. Hypoglycemic brain injury: potentiation from respiratory depression and injury aggravation from hyperglycemic treatment overshoots. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:82–92. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank HJ, Jankovic-Vokes T, Pardridge WM, Morris WL. Enhanced insulin binding to blood-brain barrier in vivo and to brain microvessels in vitro in newborn rabbits. Diabetes. 1985;34:728–733. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.8.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankland PW, Ding HK, Takahashi E, Suzuki A, Kida S, Silva AJ. Stability of recent and remote contextual fear memory. Learn Mem. 2006;13:451–457. doi: 10.1101/lm.183406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gewirtz JC, Davis M. Using pavlovian higher-order conditioning paradigms to investigate the neural substrates of emotional learning and memory. Learn Mem. 2000;7:257–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.35200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grafe MR. Developmental changes in the sensitivity of the neonatal rat brain to hypoxic/ischemic injury. Brain Res. 1994;653:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagberg H, Ichord R, Palmer C, Yager JY, Vannucci SJ. Animal models of developmental brain injury: relevance to human disease. A summary of the panel discussion from the Third Hershey Conference on Developmental Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. Dev Neurosci. 2002;24:364–366. doi: 10.1159/000069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones TW, Davis EA. Hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes: current issues and controversies. Pediatr Diabetes. 2003;4:143–150. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5448.2003.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M, Yu ZX, Fredholm BB, Rivkees SA. Susceptibility of the developing brain to acute hypoglycemia involving A1 adenosine receptor activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E562–E569. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00112.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leloup C, Magnan C, Alquier T, Mistry S, Offer G, Arnaud E, Kassis N, Ktorza A, Penicaud L. Intrauterine hyperglycemia increases insulin binding sites but not glucose transporter expression in discrete brain areas in term rat fetuses. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:263–267. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000132853.35660.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marty N, Dallaporta M, Thorens B. Brain glucose sensing, counterregulation, and energy homeostasis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:241–251. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott CJ, Bradley KN, McCarron JG, Palmer AM, Morris BJ. Striatal neurones show sustained recovery from severe hypoglycaemic insult. J Neurochem. 2003;86:383–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan JE. Hypo- and hyperglycemia and other carbohydrate metabolism disorders. In: Thureen P, Hay WW, editors. Neonatal Nutrition and Metabolism. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGowan JE, Perlman JM. Glucose management during and after intensive delivery room resuscitation. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2005.11.007. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQuillen PS, Ferriero DM. Selective vulnerability in the developing central nervous system. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mujsce DJ, Christensen MA, Vannucci RC. Regional cerebral blood flow and glucose utilization during hypoglycemia in newborn dogs. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1659–H1666. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.6.H1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nehlig A. Cerebral energy metabolism, glucose transport and blood flow: changes with maturation and adaptation to hypoglycaemia. Diabetes Metab. 1997;23:18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noh KM, Lee JC, Ahn YH, Hong SH, Koh JY. Insulin-induced oxidative neuronal injury in cortical culture: mediation by induced N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. IUBMB Life. 1999;48:263–269. doi: 10.1080/713803514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northam EA, Anderson PJ, Jacobs R, Hughes M, Warne GL, Werther GA. Neuropsychological profiles of children with type 1 diabetes 6 years after disease onset. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1541–1546. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paschen W, Siesjo BK, Ingvar M, Hossmann KA. Regional differences in brain glucose content in graded hypoglycemia. Neurochem Pathol. 1986;5:131–142. doi: 10.1007/BF03160128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick AW, Campbell IW. Fatal hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetes mellitus: clinical features and neuropathological changes. Diabet Med. 1990;7:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice D, Barone S., Jr Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2000;108:511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade: novel fluorochromes for detecting toxicant-induced neuronal degeneration. Toxicol Pathol. 2000;28:91–99. doi: 10.1177/019262330002800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherwood NM, Timiras PS. A Steriotaxic Atlas of the Developing Rat Brain. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1970. pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stead JD, Neal C, Meng F, Wang Y, Evans S, Vazquez DM, Watson SJ, Akil H. Transcriptional profiling of the developing rat brain reveals that the most dramatic regional differentiation in gene expression occurs postpartum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:345–353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenninger E, Flink R, Eriksson B, Sahlen C. Long-term neurological dysfunction and neonatal hypoglycaemia after diabetic pregnancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79:F174–F179. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.3.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suh SW, Gum ET, Hamby AM, Chan PH, Swanson RA. Hypoglycemic neuronal death is triggered by glucose reperfusion and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:910–918. doi: 10.1172/JCI30077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh SW, Hamby AM, Swanson RA. Hypoglycemia, brain energetics, and hypoglycemic neuronal death. Glia. 2007;55:1280–1286. doi: 10.1002/glia.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tkacs NC, Dunn-Meynell AA, Levin BE. Presumed apoptosis and reduced arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y and pro-opiomelanocortin mRNA in non-coma hypoglycemia. Diabetes. 2000;49:820–826. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tkacs NC, Pan Y, Raghupathi R, Dunn-Meynell AA, Levin BE. Cortical Fluoro-Jade staining and blunted adrenomedullary response to hypoglycemia after noncoma hypoglycemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1645–1655. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Towfighi J, Mauger D, Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ. Influence of age on the cerebral lesions in an immature rat model of cerebral hypoxia-ischemia: a light microscopic study. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;100:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ. Hypoglycemic brain injury. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:147–155. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vannucci SJ, Vannucci RC. Glycogen metabolism in neonatal rat brain during anoxia and recovery. J Neurochem. 1980;34:1100–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb09946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White LD, Barone S., Jr Qualitative and quantitative estimates of apoptosis from birth to senescence in the rat brain. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:345–356. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Widmaier EP. Development in rats of the brain-pituitary-adrenal response to hypoglycemia in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:E757–E763. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.5.E757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamada KA, Rensing N, Izumi Y, De Erausquin GA, Gazit V, Dorsey DA, Herrera DG. Repetitive hypoglycemia in young rats impairs hippocampal long-term potentiation. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:372–379. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000110523.07240.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada KA, Rensing N, Thio LL. Ketogenic diet reduces hypoglycemia-induced neuronal death in young rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh YY, Zee P. Insulin, a possible regulator of ketosis in newborn and suckling rats. Pediatr Res. 1976;10:192–197. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou D, Qian J, Liu CX, Chang H, Sun RP. Repetitive and profound insulin-induced hypoglycemia results in brain damage in newborn rats: an approach to establish an animal model of brain injury induced by neonatal hypoglycemia. Eur J Pediatr. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]