Abstract

Snakebites are common among the rural population of developing countries. The severity of venomous snakebites depends on several factors, including the location of the bite, the amount of venom injected, and the effectiveness of the initial therapy. Snakebites frequently occur in the extremities with approximately two thirds of envenomations occurring in the upper extremities. In this study, we presented 12 cases of hand reconstruction after Vipera snakebites and discussed how to minimize functional loss and maximize hand rehabilitation. Twelve patients bitten by Vipera between 2001 and 2006 were included in this study. Groin flaps were performed in three cases, full-thickness grafts in two cases, thenar flaps in three cases, and cross finger flaps in three cases. With medical management, spontaneous healing occurred in one case. We prefer to use flaps on the volar site of the hand and, if the bone is not exposed, full-thickness grafts on the dorsal site of the hand. We also recommend starting rehabilitation of the hand early.

Keywords: Snakebite, Vipera, Hand reconstruction

Introduction

There are over 2,700 snake species worldwide, only a minority of which are potentially lethal [25]. There is high risk of envenomation for rural populations who are engaged in nonmechanized agriculture. The family of Viperidae is seen in the Old World: Africa, Europe, and Asia. Snake venom contains several components [18]. Cytotoxic enzymes are responsible for proteolysis, cytolysis, blisters, necrosis, and gangrene. In southeast Turkey, Vipera lebetina (Fig. 1) and Vipera xanthina are the most common venomous snakes [11]. The majority of envenomations result in hematological, neurotoxic, and myotoxic complications [18].

Figure 1.

Picture of V. lebetina.

Approximately two thirds of envenomations occur on the hands and upper extremities. The ultimate severity of venomous snakebites depends on several factors, including the location of the bite, the amount of venom injected, and the effectiveness of the initial therapy [17–19]. Snakebite envenomations can cause both systemic and local complications, which can lead to mortality and morbidity [13]. After dealing with vital problems, the focus must shift to localized damage. Bites by vipers result in local pain, soft tissue swelling, regional lymphadenopathy, ecchymosis, bloody exudate from the fang marks, and local skin necrosis. Venoms produce immediate edema and vasoconstriction, and tissue necrosis is caused by both direct cellular destruction and by vascular injury around the site of envenomations. The combination of these effects lead to ischemia, gangrene, tissue loss, and possible amputation [10, 13].

Most of the studies and publications about snakebites are focused on clinical and laboratory manifestations. Deformities of the hand are common complication of a poisonous snakebite. The hand, unlike other parts of the body, lacks abundant soft tissue covering of tendons, nerves, large vessels, and joint structures. These structures are, therefore, more prone to injury after the skin has been destroyed by the snake toxin [10, 23]. In this study, we focused on snakebites of the hand and discussed differences in the treatment and reconstruction of these injuries.

Patients and Methods

Between 2001 and 2006, 12 patients (three women and nine men) whose ages ranged from 7 to 54 years old (mean age 22 ± 2.7 years) were admitted to Diyarbakir Military Hospital and Dicle University Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Most of these patients were farmers working in rural areas; two of them were soldiers. The most common site of injury was the middle finger of the right hand (Table 1). Most of the cases were admitted on the second or third day after the snakebite. Only the two soldiers were admitted at the time of the snakebite. The algorithm for the treatment of snakebite envenomation is presented in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Antivenin usages, affected areas of the hand, and surgical treatments.

| Patient no. | Antivenom (vials) | Affected areas of the hand | Performed surgery | Evaluating functional results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | Left ring finger distal phalanx | Amputation of the distal phalanx+groin flap | Good |

| 2 | 3 | Right ring finger distal phalanx | Amputation of the distal phalanx+thenar flap | 15° flexion contracture deformities in MP joint |

| 3 | 2 | Left index finger volar surface | Cross finger flap | Decreased sensibility |

| 4 | 1 | Right hand middle finger distal phalanx and middle phalanx | Groin flap | Decreased sensibility |

| 5 | 1 | Left ring finger distal phalanx palmar surface | Cross finger | 10° flexion contracture deformities in DIP joint |

| 6 | 0 | Right hand palmar thenar area | Groin flap | Good |

| 7 | 2 | Right middle finger distal phalanx | Thenar flap | Decreased sensibility |

| 8 | 4 | Right middle finger middle phalanx dorsal surface | Cross finger flap | Good |

| 9 | 2 | Right index finger distal phalanx | Thenar flap | 15° flexion contracture deformities in DIP joint |

| 10 | 0 | Dorsum of right hand | Fasciotomy+full-thickness grafting | Good |

| 11 | 1 | Right hand ring finger dorsal surface | Full-thickness grafting | Good |

| 12 | 0 | Right middle finger proximal phalanx volar surface | Medical management spontaneous healing | Good |

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the management of pit viper envenomation. LWC local wound care including immobilization of the extremity and gravity-neutral position until the neutralization of the venom.

Generally, we prefer to use flaps in pediatric patients for better functional results and follow-up. However, most of these patients were farmers working in rural areas who intended to return to their occupation as soon as possible because of crop-harvesting season. Sometimes, such patients preferred graft options, which played a role in our choices.

Results

Most of our patients were admitted on the second or third day after the snakebite. The major reason for this delay was the low socioeconomic level of the patients. Only the two military patients were attended to immediately because of the good triage of the military personnel.

At the time of presentation, all patients had tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, and abnormal blood pressure. The signs and symptoms presented by the patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The signs and symptoms presented in the patients.

| Symptoms | Frequency no. | Signs | Frequency no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 10 | Fang mark | 6 |

| Paresthesia | 7 | Swelling | 9 |

| Hyperesthesia | 2 | Discoloration | 8 |

| Fever | 12 | Bleeding | 2 |

| Tachycardia | 12 | Bullae | 4 |

| Abnormal blood pressure | 12 | Tissue necrosis | 11 |

Anemia developed in three patients with an average lowest hematocrit value of 25.2% (range, 22.3% to 29.1%). Thrombocytopenia developed in two patients with an average platelet count of 70.2 (range, 50.6 to 139.7). The prothrombin time was elevated in three patients, and partial thromboplastin time was elevated in four patients. Fibrinogen level was depressed in three patients. Fibrin degradation products were elevated in two patients.

Two patients received blood-product transfusions. In one patient, erythrocyte transfusion was performed; the other received platelet transfusion.

The average duration of hospitalization was 17.4 days (range was 8 to 26 days). Antivenin usages, the affected areas of the hand, and surgical treatments are listed in Table 1. Local wound care and antibiotherapy (first- or second-generation cephalosporin) was performed. Conservative treatment was used as much as possible, and surgery was performed when it was necessary. In one case, compartment syndrome was observed and an immediate fasciotomy was performed. After the edema subsided, primary suturing was performed. Groin flap was performed in three cases, full-thickness graft in two cases (Fig. 3), thenar flap in three cases, and cross finger flap in three cases (Fig. 4). With medical management, spontaneous healing ensued in one case. Distal phalanx amputation was performed in two cases. Early rehabilitation was undertaken in all cases.

Figure 3.

a Appearance of skin necrosis at the right hand ring finger dorsal surface (case no. 11). b Appearance of the wound after serial debridements. c Early postoperative view. Full-thickness skin graft was applied to the defect. d Late postoperative view at 7 months after grafting. e–f Excellent functional and cosmetic results of the patient.

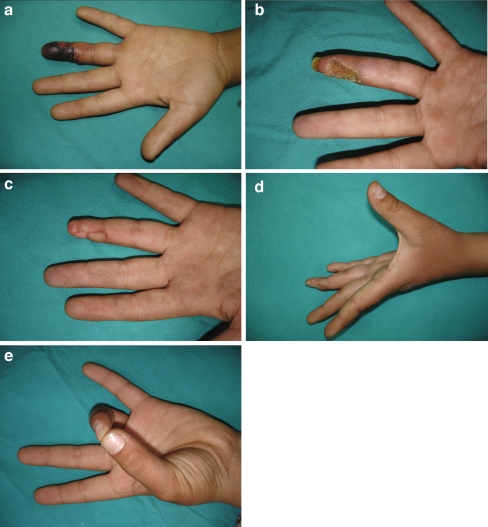

Figure 4.

a Appearance of skin necrosis at the left hand ring finger distal phalanx volar site (case no. 5). b After serial debridements, the defect was seen in the distal phalanx. c Late postoperative view at 5 months after reconstruction with cross finger flap. d–e Active extension and flexion of the left hand ring finger after reconstruction.

Discussion

Venomous snakebites, although uncommon, can cause serious mortality and morbidity [25]. It has been reported that only 10 of the 40 indigenous species found in Turkey are venomous. V. lebetina (Fig. 1) and V. xanthina are the most common venomous snakes in southeast Turkey [5].

Unfortunately, no national statistical data have been published related to the incidence of snakebites in Turkey. However, we do have a limited number of reports from some Turkish Emergency Departments. According to a retrospective study from April 2000 to April 2003, Alagözlü et al. reported 2.9% of individuals who admitted to the emergency department were poisoned by a snakebite, scorpion sting, or bee sting. Even in this report, there is no data that include only snakebites [1]. Among the 5,162 poisonings between 1990 and 1992, there were only 49 poisonings because of snakebites, scorpion sting, and bee sting; no death was reported. Seventeen snakebite victims were admitted to Bursa State Hospital between 1993 and 1995 [24].

Most of the poisonous snakes living in Turkey belong to the family Viperidae and are represented by nine species [3, 5]. V. lebetina and V. xanthina are the most common venomous snakes in south and southeast Turkey. V. xanthina (Montivipera xanthina) (Gray, 1849), also called the Ottoman viper, is a species endemic to Turkey that is found in mid, south, and west Turkey at elevations of up to 2,000 m. V. lebetina (Macrovipera lebetina) (Linnaeus, 1758) is also endemic in Turkey and is found in the east and southeast Mediterranean at elevations up to 1,500 m [24].

Among the V. xanthina specimens, the most aggressive behavior was observed in a 47-cm long snake, whereas the most submissive snake was 88-cm long. The fractions and concentrations of the venom proteins are higher in older snakes than in the younger specimens [4].

Envenoming by V. lebetina is characterized by prominent local tissue damage, hemorrhage, abnormalities in the blood coagulation system, necrosis, and edema. Recent studies have documented that the venom from snakes of the family Viperidae contains large amounts of phospholipase A2 enzymes, which are mostly toxic [7].

Siigur et al. have demonstrated the existence of both coagulants and anticoagulants in V. lebetina venom. The venom contains serine (α-fibrinogenase, β-fibrinogenase, factor V activator) and metalloproteinases (fibrinolytic enzyme lebetase, factor X activator) that affect coagulation and fibrinolysis [22].

Kinin-releasing enzymes, such as kininogenase or kallikreins, are also present in viperid venoms. They act mainly through the production of biologically potent kinins and cause hypotensive shock and severe localized pain [2].

The electrophoretic patterns of the venom proteins of five viper species living in Turkey (V. xanthina, V. ammodytes, V. wagneri, V. lebetina, and V. kaznakovi) were compared by Arıkan et al. The venom of vipers is more complex than that of colubrids. The venom proteins of the five viper species can be separated into 10 to 12 fractions or fraction groups. Among the five vipers, the total protein fraction number was highest in V. lebetina, V. ammodytes, and V. xanthina. The protein fraction number in these vipers was 12 compared to 11 in V. kaznakovi and 10 in V. wagneri [3].

There are three different antivenins available in Turkey. European Viper Venom® (Intervax Biological, Toronto, Zagreb, Croatia), which is effective against the venoms of V. ammodytes, V. aspis, V. berus, V. lebetina, V. ursinii, and V. xanthina, is the most commonly used antivenin in Turkey. Pasteur Ipser Europe® (Pasteur Merieux, Lyon, France), which is effective against the venoms of V. aspis, V. ammodytes, and V. berus, is also available in Turkey. Polyvalent Snake Venom Antiserum® (Vacsera, Giza, Egypt), which is effective against the venoms of V. ammodytes, V. lebetina, and V. xanthina, is the final antivenin available in Turkey [14].

Snakebites are usually seen in people living in rural areas, construction laborers, soldiers, and farmers working in fields or sleeping outdoors. All of the envenomations in this study occurred between late spring and early fall, due in part to crop harvesting [20]. Snakebites can present with findings that range from fang marks, with or without local pain and swelling, to life-threatening systemic symptoms and signs. Patients with snakebites should undergo a comprehensive work-up to look for possible hematologic, neurologic, renal, and cardiovascular abnormalities. Routine laboratory evaluations must be carried out on admittance to the hospital after the snakebite. Treatment should be planned depending on the grade of envenomation determined by laboratory evaluation and the degree of edema in the affected extremity [10, 13].

There is high incidence of upper extremity and hand involvement, and snakebites of the hand and upper extremity differ from snakebites on other sites of the body [10]. As it is known, the grade of envenomation is closely related to the depth of the bite [18]. In the upper extremities, especially the hand, there is almost no subcutaneous fat tissue. The dorsum of the hand is very thin, and there are many superficial veins. The palmar surface of the hand includes a rich vascular network, which makes snakebites of the hand more susceptible to systemic spreading of the venom. Moreover, vital tissues such as joints, nerves, and tendons are very superficial in the upper hand. Digital tissue necrosis is usually caused by the venom itself, especially when the patient is seen 2 to 3 days after the bite [10]. Therefore, snakebites on the hand are more urgent than snakebites elsewhere, so they must be treated at a very early stage. We think that antivenom therapy should be undertaken earlier and that larger doses should be used for neutralization of the venom in the acute period. Antivenin is administered within 4 h of the snakebite, but it is effective for at least the first 24 h [13]. Allergic reactions to antivenin are possible. The most common reaction to antivenin is an anaphylactoid reaction [18] that develops within 10–180 min of starting antivenom in 3–54% of patients. These early reactions are probably because of complement activation. The symptoms include itching, urticaria, cough, nausea, vomiting, fever, and tachycardia. Up to 40% of patients showing early reactions develop systemic anaphylaxis (hypotension, bronchospasm, and angioneurotic edema) [12].

Anaphylactoid reactions can usually be treated by stopping the antivenin infusion, administering diphenhydramine intravenously, waiting 5 min, and then restarting the infusion of antivenin at a slower rate. Anaphylaxis is treated by stopping the infusion of antivenin and administering epinephrine, corticosteroids, and crystalloid fluid infusion [18].

Serum sickness type reactions have been reported to occur in 10% to 75% of patients receiving equine antivenin. Onset of delayed serum sickness usually occurs within 3 weeks after antivenin treatment and consists of fatigue, itching, urticaria, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, periarticular swelling, albuminuria, and rarely, encephalopathy. Serum sickness can be treated with steroids and antihistamines [12, 18, 21].

It has been emphasized that patients who have had prior reactions to horse serum and those who have had previous antivenin treatments (multiple exposures to horse serum) can develop severe, delayed hypersensitivity reactions [10, 21].

In the management of snakebites in the upper extremity, true compartment syndrome must be differentiated from acute swelling. Local tissue necrosis at the site of fang marks is debrided, but no other debridement should be done at that time; serial limited debridement with dressings may be applied until the defect is seen [19]. Fasciotomies should be performed only in patients with the clinical signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome (i.e., pain on passive stretch, hypoesthesia, tenseness of compartment, and weakness), but sometimes diagnosis may be difficult [8]. Gelberman et al. have shown that a decrease in vibratory sensation may be the earliest sensory finding that is documentable and, therefore, might be useful in these cases [9]. Our experience with fasciotomies was based on clinical observations of the effected extremity (increased swelling and pain of the effected extremity). Digital tissue necrosis is usually caused by the venom itself, especially when the patient is seen 2 to 3 days later.

Because there are no compartments within the digit, finger swelling resulting in tissue necrosis would not technically be a compartment syndrome; however, neurovascular bundles within the digit would function as small compartments. When the skin of the digit, which forms a small compartment in itself, reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. According to Watt et al., when the digits are affected, dermotomy and decompression of the entire finger must be performed. The neurovascular bundle does not have to be opened, and only the subcutaneous tissue should be entered. If the procedure is done early, the functional and cosmetic results are excellent [26].

The venom of a poisonous snake is a complex of several proteins with other less significant constituents, resulting in principles which are capable of changing viable tissues. The hemotoxic factor is responsible for most of the necrosis and tissue slough, which may progress to tendon involvement, joint disturbance, and ankylosis [10].

The hand performs a unique mechanical function, so sufficient soft tissue coverage is very important. Grafting of the defects of the hand is not frequently used. Because of wound contraction, nongliding of the tendons under skin grafts may cause functional impairment. In addition, sensation, which is not achieved by skin grafts, is important for the hand. Reconstruction of the hand should be done with similar tissue whenever possible. Therefore, we preferred to cover the defects with various types of flaps, including cross finger flaps, thenar flaps, and groin flaps. Because the final postoperative appearance of fingers reconstructed with groin flaps demonstrated rather thick groin flaps, we recommend a second-stage debulking procedure for a better appearance with this type of reconstruction.

They provide better blood supply and are more durable. In two cases, amputation was performed because of tissue necrosis. Despite the fact that we suggest a more aggressive therapy, our amputation rate is higher than that found in the literature [10]. This was thought to be because of the low socioeconomic status of our patients. To prevent later sequela, snakebites are best treated acutely by surgical debridement to remove as much venom as possible. In this series, the two soldiers seen early and treated by debridement had less tissue necrosis. Unfortunately, most of the cases were agricultural laborers admitted to our clinic on the second or third day after envenomation, which was detrimental for both medical and surgical management of cases. Another important feature of snakebites is hematologic complications. The most common hematologic complications are consumption coagulopathy, diffuse vascular damage, DIC-like syndrome, localized massive clotting, hyperfibrinolysis, venom-induced thrombocytopenia, and blood vessel injury [18]. There are also articles indicating that these complications can be late-onset. Biphasic rattlesnake venom-induced thrombocytopenia was reported to occur even 1 week after envenomation [6, 15, 16]. Therefore, before any surgical intervention, coagulation studies of these patients must be done just before the operation, and it must be kept in mind that earlier studies may not reflect the current status of the patient. The patient must also be followed-up for possible complications of antivenom therapy.

In conclusion, snakebites are more commonly seen in rural areas of developing countries. There is an urgent need to educate the rural population about the hazards and treatment of snakebites. In our opinion, rapid transportation and evaluating the patient’s need for dermotomy to prevent ischemia of the finger must be addressed. We think that envenomation of the hand needs more aggressive treatment by means of medical and surgical treatment from other envenomation sites. Although surgery is not as important as antivenom therapy to snakebites, the patient must be well-evaluated before possible surgical intervention.

References

- 1.Alagözlü H, Aktaş C, Eren H. Acil servise başvuran zehirlenme olgularımızın analizi. [Article in Turkish]. Analysis of the patients with intoxication admitting to the emergency department. Medical Network Klinik Bilimler ve Doktor 2004;10:143–7.

- 2.Al-Joufi A, Bailey GS, Reddi K, et al. Neutralization of kinin-releasing enzymes from viperid venoms by antivenom IgG fragments. Toxicon 1991;29:1509–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Arıkan H, Kumlutaş Y, Türkozan O, et al. Electrophoretic patterns of some viper venoms from Turkey. Turk J Zoolog 2003;27:239–42.

- 4.Arikan H, Alpagut Keskin N, Cevik IE, et al. Age-dependent variations in the venom proteins of Vipera xanthina (Gray, 1849) (Ophidia: Viperidae). Turk Parazitol Derg 2006;30:163–5. [PubMed]

- 5.Basoglu M, Baran I. Türkiye Sürüngenleri, Kısım II, Yılanlar (Turkish Reptiles, Part II, Snakes). Ege Üniversitesi Fen Fakültesi Kitaplar Serisi No:81, sayfa 218, Bornova, İzmir, Türkiye. (İzmir Ege University Science Faculty Book Series, Bornova, İzmir, Turkey) [Article in Turkish] 1980;81:218.

- 6.Boyer LV, Seifert SA, Clark RF, et al. Recurrent and persistent coagulopathy following pit viper envenomation. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:706–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fatehi-Hassanabad Z, Fatehi M. Characterisation of some pharmacological effects of the venom from Vipera lebetina. Toxicon 2004;43:385–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Garfin SR, Castilonia RR, Mubarak SJ, et al. Rattlesnake bites and surgical decompression: results using a laboratory model. Toxicon 1984;22:177–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gelberman RH, Szabo RM, Williamson RV, et al. Sensibility testing in peripheral-nerve compression syndromes. An experimental study in humans. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:632–8. [PubMed]

- 10.Grace TG, Omer GE. The management of upper extremity pit viper wounds. J Hand Surg Am 1980;5:168–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Halıcı Z, Gepdiremen A. Snake venoms and effects on human metabolism. [Article in Turkish]. Sendrom 2003;15:76–82.

- 12.Ismail M, Memish ZA. Venomous snakes of Saudi Arabia and the Middle East: a keynote for travellers. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003;21:164–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Phys 2002;65:1367–74. [PubMed]

- 14.Kose R. The management of snake envenomation: evaluation of twenty-one snake bite cases. Turkish Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 2007;13:307–12. [PubMed]

- 15.Li QB, Yu QS, Huang GW, et al. Hemostatic disturbances observed in patients with snakebite in south China. Toxicon 2000;38:1355–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Offerman SR, Barry JD, Schneir A, et al. Biphasic rattlesnake venom-induced thrombocytopenia. J Emerg Med 2003;24:289–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Paret G, Ben-Abraham R, Ezra D, et al. Vipera palaestinae snake envenomations: experience in children. Hum Exp Toxicol 1997;16:683–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Peterson ME. Snake bite: pit vipers. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2006;21:174–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Rowland SA. Fasciotomy: the treatment of compartment syndrome. Green’s operative hand surgery. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. p. 689–710.

- 20.Sharma N, Chauhan S, Faruqi S, et al. Snake envenomation in a north Indian hospital. Emerg Med J 2005;22:118–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Shaw BA, Hosalkar HS. Rattlesnake bites in children: antivenin treatment and surgical indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84-A:1624–9. [PubMed]

- 22.Siigur J, Aaspõllu A, Tõnismägi K, et al. Proteases from Vipera lebetina venom affecting coagulation and fibrinolysis. Haemostasis 2001;31:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Smith TA 2nd, Figge HL. Treatment of snakebite poisoning. Am J Hosp Pharm 1991;48:2190–6. [PubMed]

- 24.Uğurtaş İH, Durmuş SH, Kete R. Bursa Uludağ’ da belirlenen bazı zehirli hayvanlar. [Article in Turkish]. Some poisonous animals found in Bursa Uludağ. Ekoloji Çevre Dergisi 2000;9:3–8.

- 25.Van den Enden E. Bites by venomous snakes. Acta Clin Belg 2003;58:350–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J 1985;78:694–9. [DOI] [PubMed]